December 2004 - Materials Science Institute - University of Oregon

December 2004 - Materials Science Institute - University of Oregon

December 2004 - Materials Science Institute - University of Oregon

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

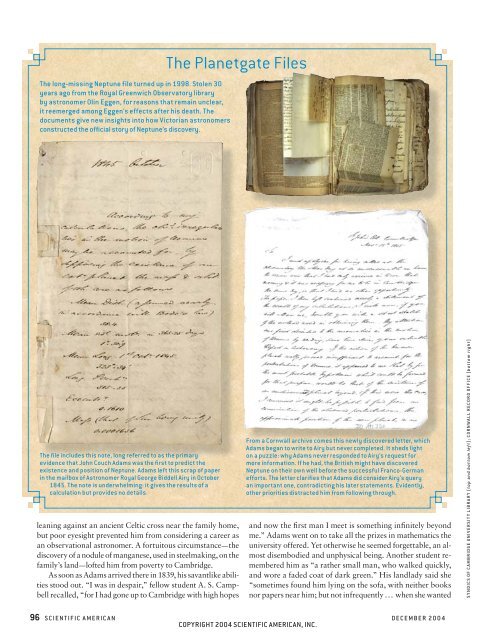

The long-missing Neptune file turned up in 1998. Stolen 30<br />

years ago from the Royal Greenwich Observatory library<br />

by astronomer Olin Eggen, for reasons that remain unclear,<br />

it reemerged among Eggen’s effects after his death. The<br />

documents give new insights into how Victorian astronomers<br />

constructed the <strong>of</strong>fi cial story <strong>of</strong> Neptune’s discovery.<br />

The fi le includes this note, long referred to as the primary<br />

evidence that John Couch Adams was the fi rst to predict the<br />

existence and position <strong>of</strong> Neptune. Adams left this scrap <strong>of</strong> paper<br />

in the mailbox <strong>of</strong> Astronomer Royal George Biddell Airy in October<br />

1845. The note is underwhelming: it gives the results <strong>of</strong> a<br />

calculation but provides no details.<br />

The Planetgate Files<br />

leaning against an ancient Celtic cross near the family home,<br />

but poor eyesight prevented him from considering a career as<br />

an observational astronomer. A fortuitous circumstance—the<br />

discovery <strong>of</strong> a nodule <strong>of</strong> manganese, used in steelmaking, on the<br />

family’s land—l<strong>of</strong>ted him from poverty to Cambridge.<br />

As soon as Adams arrived there in 1839, his savantlike abilities<br />

stood out. “I was in despair,” fellow student A. S. Campbell<br />

recalled, “for I had gone up to Cambridge with high hopes<br />

From a Cornwall archive comes this newly discovered letter, which<br />

Adams began to write to Airy but never completed. It sheds light<br />

on a puzzle: why Adams never responded to Airy’s request for<br />

more information. If he had, the British might have discovered<br />

Neptune on their own well before the successful Franco-German<br />

efforts. The letter clarifi es that Adams did consider Airy’s query<br />

an important one, contradicting his later statements. Evidently,<br />

other priorities distracted him from following through.<br />

and now the fi rst man I meet is something infi nitely beyond<br />

me.” Adams went on to take all the prizes in mathematics the<br />

university <strong>of</strong>fered. Yet otherwise he seemed forgettable, an almost<br />

disembodied and unphysical being. Another student remembered<br />

him as “a rather small man, who walked quickly,<br />

and wore a faded coat <strong>of</strong> dark green.” His landlady said she<br />

“sometimes found him lying on the s<strong>of</strong>a, with neither books<br />

nor papers near him; but not infrequently ... when she wanted<br />

96 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN DECEMBER <strong>2004</strong><br />

COPYRIGHT <strong>2004</strong> SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC.<br />

SYNDICS OF CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY (top and bottom left); CORNWALL RECORD OFFICE (bottom right)