prevalence and molecular characteristics of vibrio species in pre ...

prevalence and molecular characteristics of vibrio species in pre ...

prevalence and molecular characteristics of vibrio species in pre ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2.1 Shellfish culture<br />

CHAPTER II<br />

LITERATURE REVIEW<br />

Shellfish culture plays an important role <strong>in</strong> the world’s aquaculture <strong>in</strong>dustry.<br />

It has cont<strong>in</strong>ued to exp<strong>and</strong> with ever <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g consumer dem<strong>and</strong>s. Shrimps, oysters,<br />

mussels <strong>and</strong> crabs are some <strong>species</strong> <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> shellfish cultures. Among them<br />

shrimp is the most popular <strong>in</strong> the aquaculture <strong>in</strong>dustry.<br />

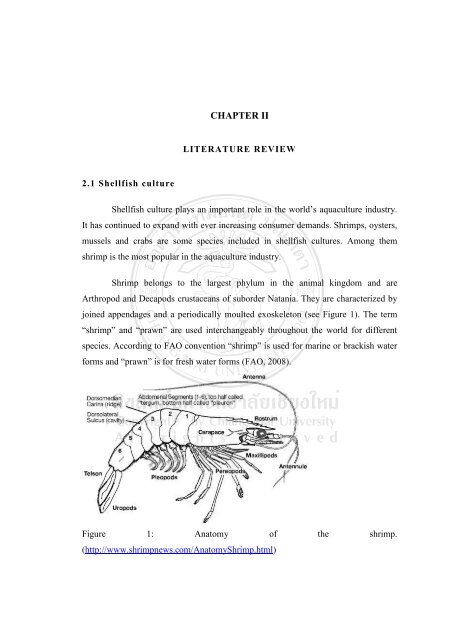

Shrimp belongs to the largest phylum <strong>in</strong> the animal k<strong>in</strong>gdom <strong>and</strong> are<br />

Arthropod <strong>and</strong> Decapods crustaceans <strong>of</strong> suborder Natania. They are characterized by<br />

jo<strong>in</strong>ed appendages <strong>and</strong> a periodically moulted exoskeleton (see Figure 1). The term<br />

“shrimp” <strong>and</strong> “prawn” are used <strong>in</strong>terchangeably throughout the world for different<br />

<strong>species</strong>. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to FAO convention “shrimp” is used for mar<strong>in</strong>e or brackish water<br />

forms <strong>and</strong> “prawn” is for fresh water forms (FAO, 2008).<br />

Figure 1: Anatomy <strong>of</strong> the shrimp.<br />

(http://www.shrimpnews.com/AnatomyShrimp.html)

2.2 Shrimp production <strong>and</strong> trade<br />

6<br />

The shrimp <strong>in</strong>dustry has boomed dur<strong>in</strong>g last two decades. South America <strong>and</strong><br />

Asia are the two <strong>pre</strong>dom<strong>in</strong>ant areas <strong>of</strong> larger scale shrimp production <strong>in</strong> the world.<br />

South Asian countries contribute 80% <strong>of</strong> the total world production. Even though<br />

there are many shrimp <strong>species</strong>, only two <strong>of</strong> them dom<strong>in</strong>ate the <strong>in</strong>dustry.<br />

1. Black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) - widely s<strong>pre</strong>ad <strong>in</strong> Asian countries,<br />

such as Thail<strong>and</strong>, Indonesia, India, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong><br />

Malaysia<br />

2. Pacific white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) - commonly found along the Eastern<br />

coast <strong>of</strong> the Pacific Ocean countries such as Brazil, Ecuador, Panama, Peru<br />

<strong>and</strong> Mexico.<br />

Currently, the white shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) is rapidly replac<strong>in</strong>g the black<br />

tiger shrimp as the ma<strong>in</strong> farmed <strong>species</strong> <strong>in</strong> Asia. This transformation started <strong>in</strong> Taipei<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> the late 1990s with the importation <strong>of</strong> specific-pathogen-free brood stock <strong>of</strong><br />

white shrimp from Hawaii <strong>and</strong> is now cultured <strong>in</strong> large scale <strong>in</strong> the People’s Republic<br />

<strong>of</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a,<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong>, Indonesia <strong>and</strong> Vietnam. The reasons for this change is that Penaeus (P.)<br />

vannamei has a faster growth, high yield, low production cost <strong>and</strong> is able to survive<br />

with a high stock<strong>in</strong>g density when compared with black tiger shrimp (Ch<strong>in</strong>abut et al.,<br />

2006). White shrimps grow to a maximum commercial size <strong>of</strong> 20g while black tiger<br />

shrimp grow up to 30g. The disadvantage <strong>of</strong> P. vannamei is the low market price <strong>in</strong><br />

the <strong>in</strong>ternational trade when compared with black tiger shrimp. Therefore large scale<br />

production is necessary <strong>in</strong> order to generate pr<strong>of</strong>its (Weerakoon, 2007).<br />

Over the last decade, the world shrimp production <strong>in</strong>creased remarkably. Data<br />

from the Food <strong>and</strong> Agriculture Organization (FAO) is shown <strong>in</strong> Table 1, the total<br />

cultured <strong>and</strong> wild harvest shrimp production <strong>in</strong> the year 2000 was 4249 thous<strong>and</strong><br />

tones <strong>and</strong> it <strong>in</strong>creased up to 6624 thous<strong>and</strong> tonnes <strong>in</strong> the year 2006. Even though wild<br />

shrimp production is seasonal <strong>and</strong> fluctuates, production rema<strong>in</strong>s more or less

7<br />

constant over the years while cultured shrimp production has steadily <strong>in</strong>creased.<br />

Cultured shrimp production re<strong>pre</strong>sented 27.3% <strong>of</strong> the total cultured <strong>and</strong> captured<br />

production <strong>in</strong> the year 2000 <strong>and</strong> it <strong>in</strong>creased by almost half (48.0%) by the year 2006<br />

(Wan Norhana et al., 2010).<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong>, Indonesia, India, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> Malaysia<br />

contribute about 60% <strong>of</strong> the world’s total cultured shrimp production (Ch<strong>in</strong>abut et al.,<br />

2006). The dem<strong>and</strong> for shrimp <strong>in</strong> world trade has also <strong>in</strong>creased steadily dur<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

last decade. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the FAO reports, <strong>in</strong> 1986, world shrimp exports totalled<br />

about 1.4 million metric tonnes <strong>and</strong> it tripled to almost 4.5 million metric tonnes by<br />

2006 (Table 2) (Wan Norhana et al., 2010).<br />

Table 1: World shrimp production from 2000 to 2006 (FAO, 2009)<br />

Source Value 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006<br />

Capture 1000<br />

tonnes<br />

US$<br />

million<br />

Aquaculture 1000<br />

tonnes<br />

US$<br />

million<br />

Total 1000<br />

tonnes<br />

US$<br />

million<br />

3087 2955 2966 3543 3527 3420 3460<br />

11,175 10,411 9788 11,621 11,357 11,458 11,764<br />

1162 1347 1496 2129 2446 2716 3164<br />

7310 7492 7879 8355 9536 10,501 12,486<br />

4249 4302 4462 5672 5973 6136 6624<br />

18,458 17,893 17,667 19,976 20,893 21,959 24250

Table 2: World exports <strong>of</strong> shrimp<br />

International export <strong>of</strong> shrimp by FAO ISSCAAP (International St<strong>and</strong>ard Statistical<br />

Classification <strong>of</strong> Aquatic Animal <strong>and</strong> Plant)<br />

Value 1986 1996 2006<br />

Tonnes 938,102 1,601,147 3,244,871<br />

US$ 1000 4,740,879 9,957,324 14,138,751<br />

2.3 Shrimp consumption<br />

8<br />

Shrimp is considered a luxury food commodity because <strong>of</strong> its unique texture<br />

<strong>and</strong> flavour. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to reports (Bragagnolo <strong>and</strong> Rodriguez-Amaya, 2001), the high<br />

cholesterol content <strong>of</strong> shrimp is compensated by the very low total lipid content <strong>and</strong><br />

the <strong>pre</strong>dom<strong>in</strong>ance <strong>of</strong> poly unsaturated fatty acids, especially the omega 3 fatty acid,<br />

which is important for human health. Another advantage <strong>of</strong> shrimp meat is the low<br />

mercury content when compared with other seafood. Consumer dem<strong>and</strong> for shrimp is<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> most developed countries. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the reports <strong>of</strong> the United States<br />

National Mar<strong>in</strong>e Fisheries Service (NMFS) shrimp consumption per capita has<br />

<strong>in</strong>creased over the years from an average <strong>of</strong> 1kg per year <strong>in</strong> 1989 to a record high <strong>of</strong><br />

1.8kg <strong>in</strong> 2005. Similarly, the European Union <strong>and</strong> Australia show a high consumer<br />

dem<strong>and</strong> for the shrimp (Wan Norhana et al., 2010).<br />

2. 4 Importance <strong>of</strong> pathogenic bacteria <strong>in</strong> shrimp production<br />

The <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> pathogenic bacteria <strong>in</strong> shrimp is closely related with<br />

environmental conditions <strong>and</strong> the microbiological quality <strong>of</strong> the water. Water<br />

temperature, salt content, distance between localization <strong>of</strong> catch <strong>and</strong> polluted areas,<br />

natural occurrence <strong>of</strong> bacteria <strong>in</strong> water, <strong>in</strong>gestion <strong>of</strong> food by the shrimp, method <strong>of</strong><br />

catch <strong>and</strong> chill<strong>in</strong>g conditions determ<strong>in</strong>e the number <strong>and</strong> the type <strong>of</strong> bacteria <strong>in</strong> the<br />

shrimp (Feldhusen, 2000).

9<br />

Pathogenic bacteria associated with seafood can be categorized <strong>in</strong> to three groups<br />

(Feldhusen, 2000). These are<br />

Indigenous bacteria: Normal component <strong>of</strong> the mar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> estuar<strong>in</strong>e<br />

environment.<br />

Eg: V. cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, V. vulnificus, Listeria monocytogenes,<br />

Clostridium botul<strong>in</strong>um, Aeromonas hydrophila (only virulent stra<strong>in</strong>s)<br />

Enteric bacteria: Due to contam<strong>in</strong>ation by the fecal material <strong>of</strong> animals <strong>and</strong><br />

human<br />

Eg: Salmonella spp., pathogenic Escherichia coli, Shigella spp.,<br />

Campylobacter spp., Yers<strong>in</strong>ia enterocolitica (very few pathogenic sero types)<br />

Bacterial contam<strong>in</strong>ation dur<strong>in</strong>g process<strong>in</strong>g: (cross contam<strong>in</strong>ation)<br />

Bacillus cereus (only toxigenic stra<strong>in</strong>s), L. monocytogenes, Staphylococcus<br />

aureus, Clostridium perfr<strong>in</strong>gens.<br />

Although many pathogenic bacteria are associated with the shrimp production<br />

cha<strong>in</strong> only a few organisms (Salmonella, Vibrio <strong>and</strong> Listeria) have been thoroughly<br />

studied for their <strong><strong>pre</strong>valence</strong> <strong>and</strong> public health importance (Wan Norhana et al., 2010).<br />

Bhaskar et al. (1998) found Salmonella <strong>and</strong> Vibrio spp. <strong>in</strong> all the samples <strong>of</strong> shrimp,<br />

sediment, feed <strong>and</strong> pond water dur<strong>in</strong>g the farm<strong>in</strong>g phase <strong>and</strong> at harvest<strong>in</strong>g time.<br />

Listeria spp. was found only <strong>in</strong> clam meat dur<strong>in</strong>g farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> sediment <strong>and</strong> shrimp at<br />

harvest. A study done <strong>in</strong> Sri Lanka revealed the <strong><strong>pre</strong>valence</strong> <strong>of</strong> Salmonella <strong>in</strong> captured<br />

<strong>and</strong> cultured shrimp 14.44% <strong>and</strong> 11.11%, respectively, <strong>and</strong> Salmonella Newport was<br />

the highest (47.83%) among the deferent Salmonella serovars followed by Salmonella<br />

Weltevreden 8.7% (Kamalika et al., 2008). Samples <strong>of</strong> processed <strong>and</strong> unprocessed<br />

shrimp from process<strong>in</strong>g plant <strong>in</strong> Nigeria was analyzed <strong>and</strong> revealed the <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong><br />

Bacillus spp., Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Enterobacter spp., Micrococus spp., E.<br />

coli, Flavobacterium spp., Staphylococus aureus, Pseudomonas spp., Rhizopus spp.,<br />

Aspergillus flavis, Aspergillus formigatus, Mucor mucido, <strong>and</strong> Sacchromyces spp., but<br />

no Vibrio spp. were isolated. This study showed a level <strong>of</strong> contam<strong>in</strong>ation by<br />

pathogenic bacteria that is hazardous for the consumer’s health (Okonko et al., 2008).

10<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Feldhusen (2000), <strong>in</strong>digenous bacteria found at low levels <strong>in</strong><br />

seafood pose an <strong>in</strong>significant hazard to the public health if the product is cooked<br />

adequately. But a few bacteria associated with faecal contam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> seafood<br />

(Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria, Yers<strong>in</strong>ia, E. coli) cont<strong>in</strong>ue to cause a large<br />

scale health threat through seafood consumption. This is worse when people have<br />

traditions <strong>of</strong> eat<strong>in</strong>g raw or under cooked seafood like <strong>in</strong> Japan. Food borne diseases<br />

lead to a significant morbidity <strong>and</strong> mortalities annually, even <strong>in</strong> developed countries<br />

where food safety is well regulated. In the United States seafood ranked third on the<br />

list <strong>of</strong> products that cause food borne illnesses dur<strong>in</strong>g 1983- 1992 (Lipp <strong>and</strong> Rose,<br />

1997). Over the past 20 years 4% <strong>of</strong> shell fish associated outbreaks were from<br />

bacterial pathogens <strong>of</strong> faecal contam<strong>in</strong>ation, while naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g bacteria<br />

accounted for 20% <strong>of</strong> shellfish-related illnesses <strong>and</strong> 99% <strong>of</strong> deaths. Most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous bacteria belong to the genera’s <strong>of</strong> Vibrio, Aeromonas <strong>and</strong> Plesiomonas<br />

(Lipp <strong>and</strong> Rose, 1997). The Center for Disease Control <strong>and</strong> Prevention (CDC)<br />

estimates that approximately 76 million new cases <strong>of</strong> food-related illnesses <strong>and</strong><br />

result<strong>in</strong>g 5,000 deaths <strong>and</strong> 325,000 hospitalizations occur <strong>in</strong> the United States each<br />

year (Group, 2010).<br />

Food borne illnesses has a significant impact on the economics <strong>of</strong> the public<br />

<strong>and</strong> private sectors. A calculation <strong>of</strong> <strong>pre</strong>cise figures for the economic impact is<br />

difficult with a high <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> food borne related illnesses. The evaluation <strong>of</strong> cost<br />

at a national level <strong>in</strong> Canada <strong>and</strong> United States based on the available data showed<br />

that company losses <strong>and</strong> legal action are much higher than the medical/<br />

hospitalization expenses, lost <strong>in</strong>come or <strong>in</strong>vestigational costs. It was estimated that<br />

one million acute bacterial food borne illnesses occur <strong>in</strong> Canada <strong>and</strong> 5.5 million cases<br />

<strong>in</strong> US cost nearly $1.1 billion <strong>and</strong> $7 billion, respectively every year (Todd, 1989).<br />

FDA estimates the economic impact <strong>of</strong> food borne illnesses from health related costs<br />

by the sum <strong>of</strong> medical cost <strong>and</strong> losses to quality <strong>of</strong> life (loss <strong>of</strong> life expectancy, pa<strong>in</strong><br />

<strong>and</strong> suffer<strong>in</strong>g functional disability). Us<strong>in</strong>g CDC data, reports estimate that food borne<br />

illness costs related to produce alone are almost $ 39 billion per year <strong>in</strong> the US<br />

(Group, 2010). In Australia there has been an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>cidence <strong>of</strong> food borne<br />

illnesses caused by E. coli O157:H7, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Hepatitis A,

11<br />

Listeriosis, <strong>and</strong> other pathogens. Annual estimated costs for these food borne<br />

outbreaks <strong>and</strong> illnesses is Au. $ 2.46 billion (Kh<strong>and</strong>aker <strong>and</strong> Alaudd<strong>in</strong>, 2005).<br />

Consumer safety <strong>and</strong> the economic impact due to food borne pathogens <strong>in</strong> the<br />

seafood forced the import<strong>in</strong>g countries to impose microbiological criteria on seafood.<br />

Each year the major import<strong>in</strong>g countries <strong>of</strong> fish <strong>and</strong> fish products reject or deta<strong>in</strong><br />

imports due to the <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> microbial pathogens. For the European Union, Vibrio<br />

spp. <strong>and</strong> Salmonella accounted for 66% <strong>of</strong> the detention <strong>of</strong> imports dur<strong>in</strong>g 1992-2002<br />

<strong>and</strong> shrimp was dom<strong>in</strong>ant among seafood products that cause detention cases. FDA<br />

categorized the <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> Salmonella, Listeria, Shigella, Hepatitis A <strong>and</strong> general<br />

term bacteria on seafood detention (FAO, 2005). Regulatory requirements for the<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> Salmonella has been established for cooked/ ready to eat <strong>and</strong> raw shrimp<br />

<strong>in</strong> EU, Australia, New Zeal<strong>and</strong>, US <strong>and</strong> Hong Kong, while ICMSF suggests that<br />

Salmonella should not be detected <strong>in</strong> 25g raw or cooked shrimp (Wan Norhana et al.,<br />

2010). Rejection <strong>of</strong> imports causes f<strong>in</strong>ancial losses to the export countries.<br />

2.5 Prevalence <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> the shrimp production cha<strong>in</strong><br />

Vibrio <strong>species</strong> are <strong>in</strong>digenous to the mar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> estuar<strong>in</strong>e environment<br />

(Bhaskar et al., 1998) <strong>and</strong> their <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>in</strong> the shrimp production cha<strong>in</strong> is to be<br />

expected. Several studies done <strong>in</strong> shrimp produc<strong>in</strong>g countries showed the <strong><strong>pre</strong>valence</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> shrimp culture environments <strong>and</strong> also the retail marketed shrimps (Table<br />

3). Only a few Vibrio <strong>species</strong> isolated are pathogenic to human <strong>and</strong> some are<br />

pathogenic to the shrimp itself. Gopal et al. (2005) <strong>in</strong>vestigated the <strong><strong>pre</strong>valence</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Vibrio <strong>in</strong> on the east <strong>and</strong> west coast <strong>of</strong> India <strong>and</strong> found Vibrio <strong>in</strong> water, shrimp <strong>and</strong><br />

sediment samples. Vibrio alg<strong>in</strong>olyticus (3-19%) V. parahaemolyticus (2-13%) V.<br />

harveyi (1-7%) <strong>and</strong> V. vulnificus (1-4%) were the <strong>pre</strong>dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>species</strong> found. The V.<br />

cholera found was negative for the cholera tox<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> from V. parahaemolyticus, 2 out<br />

<strong>of</strong> 47 isolates were tdh positive <strong>and</strong> one conta<strong>in</strong>ed the trh gene. Similarly, <strong>in</strong> a study<br />

done <strong>in</strong> Karnataka, India, by Bhaskar et al. (1998), all samples <strong>of</strong> sediment, water,<br />

shrimp, clam meat <strong>and</strong> formulated feed were contam<strong>in</strong>ated with Vibrio spp. Vibrio<br />

alg<strong>in</strong>olyticus was the most commonly isolated <strong>species</strong> found <strong>in</strong> shrimp <strong>and</strong> sediment.<br />

V. cholerae was found at a very low level but frequently <strong>in</strong> formulated feed.

12<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the author it may be due to excessive human h<strong>and</strong>l<strong>in</strong>g. In Sri Lanka<br />

Jayas<strong>in</strong>ghe et al. (2008) identified 12 <strong>species</strong> <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> shrimp us<strong>in</strong>g biochemical<br />

tests from two shrimp farms located <strong>in</strong> the West <strong>and</strong> Northwest coastal area.<br />

Aeromonas hydrophelia, V. parahaemolyticus, V. carchariae or V. harveyi <strong>and</strong><br />

Plesiomonas shigelloides were the <strong>pre</strong>dom<strong>in</strong>ant <strong>species</strong> found among them.<br />

Investigations done <strong>in</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong> reported a detection rate <strong>of</strong> 2% <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae O1 <strong>and</strong><br />

33% <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae non O1 <strong>in</strong> coastal water, pond water <strong>and</strong> shrimp (Dalsgaard et al.,<br />

1995 a).<br />

In addition to shrimp culture environments, there are reports <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> fresh<br />

<strong>and</strong> processed shrimp collected from retail markets. Investigations done <strong>in</strong> Thail<strong>and</strong><br />

revealed the <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> samples <strong>of</strong> raw seafood, processed seafood, ready-<br />

to-eat seafood <strong>and</strong> shortly boiled seafood available <strong>in</strong> food markets <strong>and</strong> supermarkets.<br />

V. alg<strong>in</strong>olyticus was the most frequently found <strong>species</strong> followed by V.<br />

parahaemolyticus, V. cholera, V. mimicus <strong>and</strong> V. vulnificus <strong>in</strong> that order (Chitov et al.,<br />

2009 b). Jonnalagadda <strong>and</strong> Bhat (2004) found a 5% <strong><strong>pre</strong>valence</strong> <strong>of</strong> Vibrio spp. <strong>in</strong><br />

shrimp purchased from the retail market <strong>in</strong> India.<br />

Table 3: Prevalence <strong>of</strong> Vibrio spp. <strong>in</strong> the shrimp production cha<strong>in</strong><br />

Po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong><br />

sampl<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Shrimp culture<br />

environment<br />

Type <strong>of</strong><br />

sample<br />

Shrimp<br />

Sediment<br />

Pond water<br />

Orig<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

sample<br />

India (East<br />

&West coast)<br />

Shrimp Iran (South<br />

coast)<br />

Coastal<br />

water<br />

Sediment<br />

Pond water<br />

Shrimp<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong><br />

(Southern)<br />

No. <strong>of</strong><br />

sample<br />

Vibrio spp. found Reference<br />

360 V. parh, V. alg,<br />

V. cho, V. vul,<br />

V. har, (14 Vibrio<br />

spp.)<br />

770 V. parh, V. dam, V.<br />

alg, V. flu<br />

158 V. cho O1<br />

V. cho non O1<br />

Gopal et al.,<br />

2005<br />

Hosse<strong>in</strong>i et al.,<br />

2004<br />

Dalsgaard et al.,<br />

1995 a

Coastal<br />

water<br />

Shrimp<br />

Bangladesh<br />

(Cox bazaar)<br />

Retail Market Shrimp India<br />

(Hyderabad)<br />

Seafoods<br />

(Shrimp)<br />

13<br />

5 V. me, V. alg, V.<br />

ner,<br />

V. har<br />

Sri Lanka 6 V. parh, V. alg,<br />

V. cho, V. vul,<br />

V. har. (12 Vibrio<br />

spp.)<br />

Thail<strong>and</strong><br />

(Chiang Mai)<br />

35 Vibrio spp. not<br />

specified.<br />

118 V. alg, V. parh,<br />

V. cho,<br />

V. mi, V. vul<br />

Rahman et al.,<br />

2010<br />

Jayas<strong>in</strong>ghe et<br />

al., 2008<br />

Jonnalagadda<br />

<strong>and</strong> Bhat, 2004<br />

Chitov et al.,<br />

2009 a<br />

V. alg=V. alg<strong>in</strong>olyticus, V. cho=V. cholerae, V. flu=V. fluvialis, V. fur=V. furnissii, V.<br />

hol=V. hollisae, V. me=V. metschnikovii, V. mi=V. mimicus, V. parh=V.<br />

parahaemolyticus, V. vul=V. vulnificus, A. hy=A. hydrophilia, P. sh=P. shigelloides,<br />

V. har=V. harveyi, V. ner=V. nereis, V. dam=V. damsela<br />

2.6 Importance <strong>of</strong> shrimp safety <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dustry<br />

2.6.1 Public health importance <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> shrimp<br />

From a public health po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>of</strong> view, concerns about shrimp safety are<br />

<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g with the expansion <strong>of</strong> the shrimp trade. Most seafood poison<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the<br />

world is caused by the Vibrio spp. orig<strong>in</strong>ates with the consumption <strong>of</strong> fresh <strong>and</strong><br />

processed seafood. But the ubiquitous nature <strong>of</strong> Vibrio makes it impossible to obta<strong>in</strong><br />

seafood free from that organism. International trade facilitates the s<strong>pre</strong>ad <strong>of</strong><br />

pathogenic micro-organisms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Vibrio spp. throughout the world. With the<br />

high dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> shrimp, the <strong>in</strong>dustry tends to <strong>in</strong>tensively use antibiotics to control<br />

diseases <strong>and</strong> to improve production. This leads to develop multi-resistant pathogenic<br />

bacteria (Wan Norhana et al., 2010). A study done <strong>in</strong> Delhi, India dur<strong>in</strong>g 2001 to<br />

2006 <strong>in</strong> hospitalized patients, found V. cholerae E1 Tor Ogawa (54.6%) more<br />

common than serotype Inaba (32.5%). But dur<strong>in</strong>g 2004 to 2006 V. cholerae Inaba<br />

emerged as the <strong>pre</strong>dom<strong>in</strong>ant serotype <strong>and</strong> showed a high resistance to nalidixic acid,

14<br />

furazolidone <strong>and</strong> cotrimazole <strong>and</strong> also for cifr<strong>of</strong>loxac<strong>in</strong>e with MIC>4mg/ml which is<br />

relatively high (Das et al., 2008). Such a serotype change (Ogawa to Inaba) may be<br />

due to <strong>pre</strong>-exist<strong>in</strong>g Ogawa antibodies or perhaps due to antimicrobial selection<br />

<strong>pre</strong>ssure. From deferent aquatic locations <strong>in</strong> Kerala, South India, multi-resistant non<br />

O1 <strong>and</strong> non O139 V. cholerae stra<strong>in</strong> were isolated <strong>and</strong> the majority <strong>of</strong> stra<strong>in</strong>s (59%)<br />

were found to be multi-drug resistant (Jagadeeshan et al., 2009). Climatic changes <strong>and</strong><br />

global warm<strong>in</strong>g impose a negative impact on the water <strong>and</strong> food borne diseases<br />

caused by micro-organisms. As shrimp is always produced <strong>in</strong> water <strong>and</strong> water is used<br />

for process<strong>in</strong>g, these changes affect the shrimp safety. A study done <strong>in</strong> Bangladesh<br />

showed that the high frequency <strong>of</strong> cholera outbreaks dur<strong>in</strong>g the El N<strong>in</strong>o Southern<br />

Oscillation, which leads to <strong>in</strong>creased surface sea water (Pascual et al., 2000). A<br />

similar study carried out <strong>in</strong> Africa also confirms the relationship between climatic<br />

change <strong>and</strong> cholera epidemics (Constant<strong>in</strong> de Magny et al., 2007). The association<br />

between the El N<strong>in</strong>o events <strong>and</strong> records <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus <strong>in</strong>fection analyzed<br />

dur<strong>in</strong>g 1994-2005 time period <strong>in</strong> Peru identified the El N<strong>in</strong>o episodes as a reliable<br />

vehicle for the <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>and</strong> propagation <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> South America (Mart<strong>in</strong>ez-<br />

Urtaza et al., 2008). With an exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g population <strong>of</strong> highly susceptible people due to<br />

ag<strong>in</strong>g, malnutrition, immune-compromisation <strong>and</strong> illnesses such as diabetes, the need<br />

for a better underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> food safety is crucial (Wan Norhana et al., 2010).<br />

Food borne outbreaks cause economic burdens on patients <strong>and</strong> their families<br />

through treatment costs, loss <strong>of</strong> productivity, suffer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> the risk <strong>of</strong> death, <strong>and</strong> also<br />

affect the public health systems <strong>of</strong> the country f<strong>in</strong>ancially (Suzita et al., 2009). Food<br />

borne illnesses due to Vibrio are reported throughout the world <strong>and</strong> are largely caused<br />

by the consumption <strong>of</strong> seafood. Seven epidemics <strong>of</strong> cholera have been recorded s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

1817 <strong>and</strong> the 8 th one is <strong>in</strong> progress (Table 4). Dur<strong>in</strong>g 1992, the epidemic <strong>of</strong> V.<br />

cholerae O139 orig<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>in</strong> the Bengal region <strong>of</strong> India <strong>and</strong> s<strong>pre</strong>ad through India,<br />

eventually to Bangladesh, Nepal, Burma, Pakistan, Thail<strong>and</strong>, Ch<strong>in</strong>a, Malaysia <strong>and</strong><br />

Saudi Arabia. Imported cases were reported <strong>in</strong> the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom <strong>and</strong> the United<br />

States. Some suggest it as 8 th cholera p<strong>and</strong>emic due to its rapid s<strong>pre</strong>ad with<strong>in</strong> a 2 year<br />

period (Kaysner, 2000).

Table 4: Cholera p<strong>and</strong>emics<br />

P<strong>and</strong>emic Dates Orig<strong>in</strong> Biotype<br />

I. 1817-1823 Indian subcont<strong>in</strong>ent -<br />

II. 1829-1851 Indian subcont<strong>in</strong>ent -<br />

III. 1852-1859 Indian subcont<strong>in</strong>ent -<br />

IV. 1863-1879 Indian subcont<strong>in</strong>ent -<br />

V. 1881-1896 Indian subcont<strong>in</strong>ent -<br />

VI. 1899-1923/5 Indian subcont<strong>in</strong>ent Classical<br />

VII. 1961-Present Indonesia O1 classical,<br />

15<br />

O1 E1 Tor<br />

VIII. 1992-Present Indian subcont<strong>in</strong>ent O139 serotype<br />

V. parahaemolyticus is the most common cause <strong>of</strong> food borne disease <strong>in</strong> the<br />

Asian region. In Japan, it has been implicated as a cause <strong>of</strong> at least a quarter <strong>of</strong> the<br />

total food borne diseases (Feldhusen, 2000). In Korea, food borne outbreaks due to<br />

Vibrio from 2003 to 2006 were 80, <strong>and</strong> 2261 human <strong>in</strong>fections were recorded (Lee et<br />

al., 2008 a). S<strong>in</strong>ce 1996 V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 is considered to be the first<br />

p<strong>and</strong>emic stra<strong>in</strong> due to its s<strong>pre</strong>ad from India to many countries with<strong>in</strong> a short period<br />

<strong>of</strong> time. Western countries also experienced gastroenteritis due to V.<br />

parahaemolyticus (Cabanillas-Beltrán et al., 2006).<br />

2.6.2 Regulatory perspective <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> shrimp<br />

Japan, the European Union <strong>and</strong> the United States are the largest seafood<br />

importers <strong>and</strong> account for 82% <strong>of</strong> the total volume <strong>of</strong> seafood imports <strong>in</strong> the world<br />

(FAO, 2005). Increas<strong>in</strong>g awareness <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> consumers for safe <strong>and</strong> high<br />

quality food forced the governments to impose strict regulations <strong>and</strong> rules on food

16<br />

safety to assure safety <strong>of</strong> the public health. Import<strong>in</strong>g countries imposed different<br />

quality <strong>and</strong> safety policies on imported food <strong>and</strong> it leads to border control, rejection,<br />

or deta<strong>in</strong>ment <strong>of</strong> the product. This leads to direct <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>direct f<strong>in</strong>ancial losses to the<br />

exporters. Seafood becomes the most common product that causes notification on<br />

import alerts. The <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> pathogenic micro-organisms is one <strong>of</strong> the common<br />

causes for detention (Wan Norhana et al., 2010).<br />

The EU committee on Rapid Alarm System for Food <strong>and</strong> Feed (RASFF)<br />

showed the highest notification <strong>of</strong> Vibrio on fish, crustaceans <strong>and</strong> mollusks dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

2001 to 2003 <strong>and</strong> accounted for 29.3% out <strong>of</strong> total food groups. Out <strong>of</strong> seafood types<br />

75% <strong>of</strong> the cases were due to frozen shrimp. Dur<strong>in</strong>g 1999-2002 border cases reported<br />

<strong>in</strong> the EU regard<strong>in</strong>g microbial risk, Vibrio spp. showed highest occurrence (39.8%)<br />

followed by the Salmonella (27.7%). The EU countries do not have harmonized<br />

criteria for Vibrio organisms (FAO, 2005). Meanwhile import detention by the Food<br />

<strong>and</strong> Drug Adm<strong>in</strong>istration (FDA) <strong>in</strong> United States for seafood products accounted for<br />

almost 27% <strong>of</strong> the total detentions <strong>in</strong> 2001 (Wan Norhana et al., 2010). Investigations<br />

carried out on seafood imported from Hong Kong, Indonesia, Thail<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Vietnam<br />

to Taiwan revealed 45.9% <strong>of</strong> samples positive for V. parahaemolyticus. The <strong>in</strong>cidence<br />

rate <strong>in</strong> shrimp was high (75.8%) when compared with other seafood such as crabs,<br />

snails <strong>and</strong> lobsters (Wong et al., 1999).<br />

Several countries <strong>and</strong> food authorities set microbiological criteria on raw<br />

seafood <strong>and</strong> ready-to-eat seafood <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g shrimp to safeguard their consumers<br />

(Table 5). A regulatory requirement for the absence <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae has been<br />

established <strong>in</strong> Hong Kong, the United States, International Commission <strong>of</strong><br />

Microbiological Specification for Food (ICMSF), the European Union, the United<br />

K<strong>in</strong>gdom <strong>and</strong> Australia. Only the FDA stated that the absence <strong>of</strong> any serotype <strong>of</strong> V.<br />

cholerae O1 or non O1 as a criteria to remove the food from the food cha<strong>in</strong>. Presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus <strong>in</strong> the food is accepted <strong>in</strong> all countries but they set different<br />

accepted levels. The accepted level <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus <strong>in</strong> raw shrimp at time <strong>of</strong><br />

sale should be less than 100 cfu/g <strong>in</strong> Netherl<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> raw, frozen <strong>and</strong> cooked require<br />

similar values (

17<br />

parahaemolyticus should be Kanagawa positive or negative <strong>and</strong> greater than 10 4 cfu /g<br />

to remove the product from the food cha<strong>in</strong>. Vibrio vulnificus is only focus by the<br />

FDA. Shrimp that have lethal pathogenic organisms are rejected or recalled from the<br />

market.<br />

Table 5: Microbiological criteria for Vibrio spp. <strong>in</strong> shrimp <strong>and</strong> shrimp products.<br />

Country/food<br />

authority<br />

Microbiological<br />

criteria/max. limits<br />

Raw shrimp(Fresh/frozen) RTE/cooked shrimp<br />

United States - V. cholerae: <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong><br />

Australia/New<br />

Zeal<strong>and</strong><br />

V. cholerae/g: n=5, c=0, m=0<br />

toxogenic O1 or non O1<br />

V. parh: levels =

18<br />

Today export countries must adapt those rules <strong>and</strong> regulations to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><br />

trade opportunities. It appears that many countries, especially the poorest may face a<br />

major problem <strong>in</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g food safety st<strong>and</strong>ards that are obligatory <strong>in</strong> a number <strong>of</strong><br />

import<strong>in</strong>g countries.<br />

2.7 Vibrio<br />

2.7.1 History <strong>and</strong> Morphology<br />

The first Vibrio spp. identified was Vibrio cholera, discovered <strong>in</strong> 1854 by the<br />

Italian physician Filppo Pac<strong>in</strong>i dur<strong>in</strong>g an outbreak <strong>and</strong> subsequent <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>in</strong><br />

Florence. Pac<strong>in</strong>i detected V. cholerae <strong>in</strong> all <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al mucosal samples <strong>of</strong> fatal<br />

victims. John Snow (1813-1858) studied the epidemiology <strong>of</strong> cholera <strong>in</strong> several cities<br />

<strong>of</strong> Engl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> found that cholera is s<strong>pre</strong>ad by the contam<strong>in</strong>ated water <strong>and</strong> suggested<br />

pure water for dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g (Thompson et al., 2004).<br />

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the Bergey’s Manual (Holt et al., 1994) this bacteria is <strong>in</strong> the<br />

family Vibrionaceae <strong>and</strong> genus Vibrio <strong>and</strong> has <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>of</strong> straight or curved<br />

rods, (0.5-0.8µm <strong>in</strong> width <strong>and</strong> 1.4-2.6 µm <strong>in</strong> length), motility by one or more polar<br />

flagella, Gram negative, chemoorganotropic, facultative anaerobic, mesophilic,<br />

oxidase positive <strong>and</strong> sensitive to the <strong>vibrio</strong>static agent O/129 (except a few <strong>species</strong>).<br />

Most <strong>species</strong> grow well at 37°C. Vibrio is distributed worldwide <strong>and</strong> is found <strong>in</strong> sea<br />

water, fresh water, brackish water <strong>and</strong> associated with aquatic animals, sediments <strong>and</strong><br />

feeds (Bhaskar et al., 1998). Large numbers <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>and</strong> Photobacterium attach to<br />

the external surface <strong>of</strong> the zooplankton <strong>and</strong> make bio films. Because <strong>of</strong> this close<br />

association with zooplankton, it is assumed that cholera outbreaks are l<strong>in</strong>ked to<br />

planktonic blooms <strong>and</strong> ris<strong>in</strong>g sea water temperature due to global warm<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(Thompson et al., 2004).

19<br />

2.7.2 Biochemical <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>of</strong> Vibrio<br />

Biochemical <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>of</strong> Vibrio are used to differentiate the food<br />

associated with Vibrio pathogens <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Aeromonas hydrophila <strong>and</strong> Plesiomonas<br />

shigelloides that belong to the family Vibrionaceae (Table 6) (Kaysner, 2000).<br />

Thiosulfate citrate-bile salt agar (TCBS) is a selective medium for the isolation <strong>of</strong><br />

Vibrio (Thompson et al., 2004). Vibrio organism’s ability to ferment sucrose <strong>and</strong> a<br />

colour change <strong>of</strong> the colony helps to differentiate Vibrio spp. Sucrose positive, yellow<br />

colonies on TCBS agar are <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae, V. fluvialis, V. furnissii, V.<br />

alg<strong>in</strong>olyticus, V. metschnikovii. While V. parahaemolyticus, V. mimicus, V. vulnificus<br />

<strong>and</strong> V. hollisae are sucrose negative <strong>and</strong> produced green colour colonies.<br />

Table 6: Biochemical <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>of</strong> the Vibrionaceae commonly encountered<br />

<strong>in</strong> seafood<br />

V.<br />

alg<br />

V. cho V.<br />

flu<br />

V.<br />

fur<br />

V. hol V. me V. mi V.<br />

parh<br />

V. vul A.<br />

TCBS agar Y Y Y Y NG Y G G G Y G<br />

Oxidase + + + + + - + + + + +<br />

Arg<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>e<br />

dihydrolase<br />

Lys<strong>in</strong>e<br />

decaboxylase<br />

Growth <strong>in</strong><br />

(w/v):<br />

- - + + - + - - - + +<br />

+ + - - - + + + + V +<br />

0% NaCl - + - - - - + - - + +<br />

3% NaCl + + + + + + + + + + +<br />

6% NaCl + - + + + + - + + + -<br />

8% NaCl + - V + - V - + - - -<br />

10% NaCl + - - - - - - - - - -<br />

Growth<br />

at 42 o C<br />

Acid from:<br />

+ + V - nd V + + + V +<br />

Sucrose + + + + - + - - - V -<br />

D-Cellobiose - - + - - - - V + + -<br />

Lactose - - - - - - - - + V -<br />

Arab<strong>in</strong>ose - - + + + - - + - V -<br />

D-Mannose + + + + + + + + + V -<br />

hy<br />

P.<br />

sh

20<br />

D-Mannitol + + + + - + + + V + -<br />

ONPG - + + + - + + - + + -<br />

Voges-<br />

Proskauer<br />

+ V - - - + - - - + -<br />

Y= yellow, G= green, NG= no or poor growth, nd= not done, V=variable among<br />

stra<strong>in</strong>s, R=resistant, S=susceptible<br />

V. alg=V. alg<strong>in</strong>olyticus, V. cho=V. cholerae, V. flu=V. fluvialis, V. fur=V. furnissii, V.<br />

hol=V. hollisae, V. me=V. metschnikovii, V. mi=V. mimicus, V. parh=V.<br />

parahaemolyticus, V. vul=V. vulnificus, A. hy=A. hydrophilia, P. sh=P. shigelloides<br />

Currently, 72 <strong>species</strong> are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the Vibrio genus <strong>and</strong> 12 <strong>species</strong> are<br />

commonly isolated <strong>in</strong> human patients. From these 12 <strong>species</strong>, V. cholera, V.<br />

parahaemolyticus <strong>and</strong> V. vulnificus are the most harmful to humans. Other Vibrio spp.<br />

isolated from humans are V. alg<strong>in</strong>olyticus, V. fluvialis, V. mimicus, V. (Grimontia)<br />

holisae, V. (Photobacterium) damsel, V. furnssii, V. c<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>natiensis, V. harveyi, <strong>and</strong><br />

V. metschnikovii.<br />

2.7.3 Growth parameters <strong>of</strong> Vibrio spp.<br />

Table 7 shows the growth limit<strong>in</strong>g factors <strong>of</strong> major human pathogenic Vibrio spp.<br />

Table 7: Growth limit<strong>in</strong>g factors <strong>of</strong> Vibrio (FAO, 2003)<br />

Species Temperature<br />

o<br />

C<br />

pH aW NaCl (%)<br />

M<strong>in</strong> Max M<strong>in</strong> M<strong>in</strong> Max<br />

V. cholerae 10 37 5.0 0.97 8<br />

V. parh 5 37 4.8 0.93 8-10<br />

V. vulnificus 8 37 5.0 0.96 5<br />

V. parh = V. parahaemolyticus

21<br />

2.7.4 Genotypic <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>of</strong> Vibrio<br />

Researchers have <strong>in</strong>vestigated the phenotypic <strong>and</strong> genotypic characterization<br />

<strong>of</strong> the Vibrio organism us<strong>in</strong>g new <strong>molecular</strong> technology based on the ribotyp<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong><br />

polymerase cha<strong>in</strong> reaction technique such as amplified fragmented length<br />

polymorphism (AFLP), fluorescence <strong>in</strong> situ hybridization (FISH) or multi locus<br />

sequence typ<strong>in</strong>g (MLST) (Thompson et al., 2004). Identification <strong>of</strong> toxigenic genes<br />

<strong>and</strong> serogroups (Dalsgaard et al., 2001, Janssen et al., 1996, Raghunath et al., 2008),<br />

genetic diversity (Jiang et al., 2000, Sawabe et al., 2002, Zo et al., 2002), ecological<br />

<strong>in</strong>teraction <strong>and</strong> relatedness <strong>of</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> environmental isolates (Zo et al., 2002) <strong>of</strong><br />

Vibrio has been carried out with the help <strong>of</strong> new techniques. Toxigenic Vibrio<br />

cholerae O1 samples from the aquatic environment <strong>and</strong> human <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>es isolated<br />

from Bangladesh were analyzed by enterobacterial repetitive <strong>in</strong>tergenic consensus<br />

sequence-PCR, optimized for pr<strong>of</strong>il<strong>in</strong>g by us<strong>in</strong>g the fully sequenced V. cholerae E1<br />

Tor N16961 genome. A study found a similar composition <strong>of</strong> environmental toxigenic<br />

V. cholerae <strong>and</strong> the V. cholerae that causes the endemic cholera. Authors conclude<br />

that the spatial <strong>and</strong> temporal fluctuation (seasonal fluctuations <strong>in</strong> the environment,<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>of</strong> new stra<strong>in</strong>) <strong>in</strong> the composition <strong>of</strong> the toxigenic V. cholerae population<br />

<strong>in</strong> the aquatic environment can cause shifts <strong>in</strong> the dynamics <strong>of</strong> this disease (Zo et al.,<br />

2002). An <strong>in</strong>vestigation carried out by Jiang et al. (2000) detected V. cholerae isolates<br />

<strong>in</strong> Chesapeake Bay coastal waters. The genetic diversity analyzed by apply<strong>in</strong>g AFLP<br />

f<strong>in</strong>gerpr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g revealed the l<strong>in</strong>k between the shift <strong>of</strong> the genotype <strong>and</strong> environmental<br />

changes such as water temperature.<br />

MLST was developed recently <strong>and</strong> considered as most reliable <strong>molecular</strong> tool<br />

for the epidemiology. This method is based on the sequence analysis <strong>of</strong> housekeep<strong>in</strong>g<br />

(HK) genes <strong>of</strong> the organism. Higher discrim<strong>in</strong>atory power, accuracy <strong>and</strong> portability <strong>of</strong><br />

the data, ease <strong>of</strong> performance, <strong>and</strong> reproducibility are major advantages <strong>of</strong> this<br />

method (Thompson et al., 2004). Nucleic acid sequences are stored <strong>in</strong> a public data<br />

base that can be easily accessed via <strong>in</strong>ternet (http://www.mlst.net or<br />

http://pubmlst.org) (González-Escalona et al., 2008). Scientist applied this method to<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e the global epidemiology <strong>of</strong> bacterial pathogens. González-Escalona et al.

22<br />

(2008) analyzed the genetic relatedness <strong>and</strong> geographical distribution <strong>of</strong> V.<br />

parahaemolyticus from the environment <strong>and</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s us<strong>in</strong>g seven house<br />

keep<strong>in</strong>g genes (dnE, gyrB, recA, dtdA, pntA, pyrC, tnaA).<br />

2.7.5 Molecular <strong>and</strong> genetic <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>of</strong> environmental Vibrio<br />

Vibrio <strong>species</strong> are widely distributed <strong>in</strong> the aquatic environment <strong>and</strong> are<br />

considered as autochthonous bacteria <strong>in</strong> the estuar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong> mar<strong>in</strong>e waters (Nishibuchi<br />

<strong>and</strong> Kaper, 1995). Scientists isolated <strong>and</strong> identified this organism <strong>in</strong> the mar<strong>in</strong>e water<br />

(Faruque et al., 2004, Nair et al., 1988), shrimp <strong>and</strong> oysters (Dalsgaard et al., 1995 a,<br />

Gopal et al., 2005, Sobr<strong>in</strong>ho et al., 2010), sediments (Bhaskar <strong>and</strong> Setty, 1994),<br />

plankton (Lipp <strong>and</strong> Rose, 1997), <strong>and</strong> also from the seafood (Chitov et al., 2009 b,<br />

Sujeewa et al., 2009). Many <strong>in</strong>vestigations were carried out to identify genetic <strong>and</strong><br />

phenotypic differences between cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> environmental <strong>vibrio</strong>s.<br />

V. cholerae serogroups O1 <strong>and</strong> O139 caused the epidemics <strong>of</strong> cholera. But<br />

other non O1 <strong>and</strong> non O139 serogroups can cause sporadic diarrhoea. Environmental<br />

stra<strong>in</strong>s ma<strong>in</strong>ly belong to V. cholerae serogroup non O1 <strong>and</strong> non O 139 (Faruque et al.,<br />

2004). Cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s carry the virulence factors for cholera tox<strong>in</strong> (CT) <strong>and</strong> tox<strong>in</strong>-<br />

coregulated pilus (TCP) which is central to the disease process <strong>and</strong> provide adhesion<br />

for the tox<strong>in</strong>s respectively (Chakraborty et al., 2000). Studies found that<br />

environmental stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae rarely carried CT <strong>and</strong> TCP. Water samples from<br />

two major rivers <strong>of</strong> Bangladesh were <strong>in</strong>vestigated for the <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae <strong>and</strong><br />

their virulence associated genes. V. cholerae non O1 <strong>and</strong> non O139 was found <strong>in</strong><br />

89.9% (116/125) <strong>and</strong> 3.2% (4/125) were V. cholerae O1 (Faruque et al., 2004). These<br />

authors found one V. cholerae O1 carry<strong>in</strong>g the TCP <strong>and</strong> CT gene (0.8%) <strong>in</strong> those<br />

environmental samples. Nair et al. (1988) carried out an <strong>in</strong>vestigation on V. cholerae<br />

non O1 from environmental sources <strong>in</strong> India, to describe tox<strong>in</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>ile. They exam<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

for the production <strong>of</strong> CT, shiga-like tox<strong>in</strong> (vero tox<strong>in</strong>), heat stable enterotox<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong><br />

haemolys<strong>in</strong>s. Two <strong>of</strong> the stra<strong>in</strong>s (0.5%) produced CT; none <strong>of</strong> them produced shiga-<br />

like tox<strong>in</strong> or heat stable enterotox<strong>in</strong>s. Haemolytic activity was observed <strong>in</strong> 89.7% <strong>of</strong><br />

the stra<strong>in</strong>s. The authors concluded that only a small percentage <strong>of</strong> environmental V.<br />

cholerae non O1 has the ability <strong>of</strong> caus<strong>in</strong>g cholera like symptoms (Nair et al., 1988).

23<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus have the ability to produce<br />

thermostable direct haemolys<strong>in</strong> (TDH) <strong>and</strong> TDH related haemolys<strong>in</strong> (TRH) <strong>and</strong> can<br />

cause gastroenteritis <strong>in</strong> humans (Su <strong>and</strong> Liu, 2007, Vongxay et al., 2006). Most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

tdh positive stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus exhibit the Kanagawa phenomenon, an<br />

enzymatic lysis <strong>of</strong> red blood cells on Wagatsuma blood agar plates (Su <strong>and</strong> Liu, 2007,<br />

Vongxay et al., 2008). Several <strong>in</strong>vestigations found that only 1-3% <strong>of</strong> the<br />

environmental stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus exhibit the toxic activity (Lee et al.,<br />

2008a, Vongxay et al., 2006, Sobr<strong>in</strong>ho et al., 2010), (Table 8). But recent reports on<br />

the <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> virulence genes <strong>in</strong> environmental stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus<br />

found an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g percentage <strong>of</strong> tdh <strong>and</strong> trh gene-carry<strong>in</strong>g stra<strong>in</strong>s (Deepanjali et al.,<br />

2005, Raghunath et al., 2008, Sujeewa et al., 2009, Zimmerman et al., 2007) (Table<br />

8). Those studies showed that, trh-bear<strong>in</strong>g V. parahaemolyticus are more frequently<br />

distributed <strong>in</strong> tropical seafood than tdh-bear<strong>in</strong>g V. parahaemolyticus.<br />

V. vulnificus is an opportunistic human pathogen (Cañigral et al., 2009) <strong>and</strong><br />

unlike V. parahaemolyticus <strong>and</strong> V. cholerae, environmental <strong>and</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V.<br />

vulnificus showed no difference <strong>in</strong> the potential to produce tox<strong>in</strong>s. Human V.<br />

vulnificus <strong>in</strong>fections shows cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs <strong>of</strong> wound <strong>in</strong>fection, fever, chills,<br />

hypotension, bulbous like sk<strong>in</strong> lesions which are rapidly progressive <strong>and</strong> 50%<br />

mortality <strong>in</strong> septicaemia conditions. The polysaccharide capsule <strong>and</strong> the production <strong>of</strong><br />

siderphores by this organism are considered as virulence factors (Starks et al., 2000).<br />

Tison <strong>and</strong> Kell (1986) studied the virulence <strong>of</strong> V. vulnificus isolated from the mar<strong>in</strong>e<br />

environment. These authors found no difference <strong>in</strong> their production <strong>of</strong> virulence<br />

factors, both <strong>in</strong> vitro (cytolys<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> cytotox<strong>in</strong>) <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> vivo (mouse pathogenicity)<br />

among cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>and</strong> environmental isolates <strong>of</strong> V. vulnificus. Similar to this study,<br />

Wong et al. (2005) also found that environmental stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. vulnificus exhibit a<br />

similar virulence to cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> mice. These data were supported by Stelma et<br />

al. (1992).

24<br />

Table 8: Prevalence <strong>of</strong> tdh <strong>and</strong> trh genes <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus <strong>in</strong><br />

environmental samples.<br />

Country/<br />

place<br />

Type <strong>of</strong><br />

samples (no<br />

<strong>of</strong> samples)<br />

Prevalence<br />

% <strong>of</strong> V.<br />

parh.<br />

Presence <strong>of</strong><br />

tdh gene <strong>in</strong><br />

%<br />

Presence <strong>of</strong><br />

trh gene <strong>in</strong><br />

%<br />

References<br />

Korea Raw oysters - 0 1.38 Lee et al., 2008<br />

(72)<br />

a<br />

Brazil Raw oysters 99.2 0.8 0 Sobr<strong>in</strong>ho et al.,<br />

(123)<br />

2010<br />

India Shrimp, 2-13 4 2.12 Gopal et al.,<br />

sediment,<br />

water<br />

2005<br />

Ch<strong>in</strong>a Samples from 14.3 5.8 0 Vongxay et al.,<br />

seafood<br />

process<strong>in</strong>g<br />

l<strong>in</strong>e (258)<br />

2006<br />

Malaysia Frozen<br />

51 15 7 Sujeewa et al.,<br />

shrimp (60),<br />

2009<br />

live<br />

(50),<br />

shrimp<br />

sediment<br />

(67),<br />

(74).<br />

water<br />

Southwest Raw Oysters 93.9 10.2 59.3 Deepanjali et<br />

coast <strong>of</strong> India<br />

al., 2005<br />

Southwest<br />

coast <strong>of</strong> India<br />

Northern<br />

Gulf <strong>of</strong><br />

Mexico<br />

Oysters (44),<br />

clams (14),<br />

fish (9),<br />

shrimp (16),<br />

seafood (83)<br />

Oysters (32)<br />

Water (102)<br />

V. parh. =V. parahaemolyticus<br />

89.2 8.4 25.3 Raghunath et<br />

al., 2008<br />

56/44<br />

78/30<br />

56<br />

44<br />

78<br />

30<br />

Zimmerman et<br />

al., 2007

2.8 Human pathogenic Vibrio<br />

2.8.1 Vibrio cholerae<br />

25<br />

Cholera has been recognized as a fatal disease s<strong>in</strong>ce 1817 <strong>and</strong> six p<strong>and</strong>emics<br />

have already swept over the world (Suzita et al., 2009) <strong>and</strong> the 7 th <strong>and</strong> 8 th p<strong>and</strong>emics<br />

are still progress<strong>in</strong>g (Kaysner, 2000). Vibrio cholera is transmitted to humans via<br />

contam<strong>in</strong>ated food, water, raw seafood or direct <strong>in</strong>fection from food h<strong>and</strong>lers (Suzita<br />

et al., 2009, Thompson et al., 2004). Cholera is characterized by pr<strong>of</strong>use acute<br />

diarrhoea (rice water), vomit<strong>in</strong>g, dehydration <strong>and</strong> death with<strong>in</strong> 24 hours if left<br />

untreated (Suzita et al., 2009). The pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> this organism <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>e is<br />

characterized by adherence to the epithelium <strong>and</strong> production <strong>of</strong> an enterotox<strong>in</strong><br />

(cholera tox<strong>in</strong>) which leads to <strong>in</strong>tense watery diarrhoea. In addition to the tox<strong>in</strong>, the<br />

tox<strong>in</strong> coregulated pilus is essential for the micro colonization <strong>of</strong> the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al<br />

epithelium (Thompson et al., 2004).<br />

Currently more than 200 serogroups <strong>of</strong> V. cholera are identified based on the<br />

somatic O antigen. Vibrio cholera O1, O139, non-O1, non-O139 <strong>and</strong> O141 are the<br />

deferent O stra<strong>in</strong>s that cause diarrhoea throughout the world. V. cholerae O1 has two<br />

serogroups Inaba <strong>and</strong> Ogawa <strong>and</strong> two biotypes namely, Classical <strong>and</strong> El Tor (Ganesh<br />

et al., 2010, Suzita et al., 2009). Serogroup O1 <strong>and</strong> O139 are responsible for the<br />

epidemics <strong>and</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic occurrences <strong>of</strong> cholera <strong>and</strong> non-O1 <strong>and</strong> non-O139 are less<br />

virulent forms found <strong>in</strong> patients. V. cholerae O141 causes cholera-like diarrhoea <strong>and</strong><br />

bacteraemia <strong>in</strong> the United States (Crump et al., 2003).<br />

2.8.2 Vibrio parahaemolyticus<br />

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a Gram negative, mesophilic <strong>and</strong> halophilic rod-<br />

shaped bacterium found <strong>in</strong> the estuar<strong>in</strong>e environment, especially <strong>in</strong> shellfish, coastal<br />

fish <strong>and</strong> seafood. Consumption <strong>of</strong> raw, under cooked or contam<strong>in</strong>ated shellfish, fish<br />

<strong>and</strong> seafood is the method <strong>of</strong> transmission <strong>of</strong> this bacterium to humans. It causes<br />

gastroenteritis, nausea, watery diarrhoea, vomit<strong>in</strong>g, abdom<strong>in</strong>al cramps, low grade<br />

fever, chills <strong>and</strong> sometimes bloody diarrhoea (Cabanillas-Beltrán et al., 2006). V.<br />

parahaemolyticus produces tox<strong>in</strong>s: thermo-stable direct haemolys<strong>in</strong> (TDH), encoded

26<br />

by the tdh gene <strong>and</strong> the TDH related haemolys<strong>in</strong> (TRH) encoded by the trh-gene. The<br />

production <strong>of</strong> the TDH tox<strong>in</strong> can be detected biochemically by the Kanagawa<br />

reaction, <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g beta-haemolysis on Wagatsuma blood agar. The trh-gene can be<br />

detected by PCR (Thompson et al., 2004).<br />

The first p<strong>and</strong>emic stra<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus O3:K6 appeared <strong>in</strong> Calcutta,<br />

India <strong>and</strong> rapidly s<strong>pre</strong>ad to many countries s<strong>in</strong>ce 1996. Dur<strong>in</strong>g 2003-2004 the same<br />

serotype O3:K6 appeared <strong>in</strong> Mexico <strong>and</strong> caused gastroenteritis affect<strong>in</strong>g more than<br />

1230 human cases (Cabanillas-Beltrán et al., 2006).<br />

2.8.3 Vibrio vulnificus<br />

Vibrio vulnificus is a halophilic bacteria naturally found <strong>in</strong> the estuar<strong>in</strong>e <strong>and</strong><br />

coastal waters. Gastroenteritis, severe necrotization <strong>of</strong> the s<strong>of</strong>t tissue <strong>and</strong> primary<br />

septicaemia with a high mortality rate are the cl<strong>in</strong>ical signs. Consumption <strong>of</strong> V.<br />

vulnificus contam<strong>in</strong>ated food <strong>and</strong> exposure to the contam<strong>in</strong>ated water causes the<br />

illness (Cañigral et al., 2009). Septicaemia occurs ma<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong> immunosup<strong>pre</strong>ssed<br />

people <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> patients with high levels <strong>of</strong> serum iron due to liver disease or genetic<br />

disorders. The primary virulence factor <strong>of</strong> V. vulnificus, the capsular polysaccharide,<br />

plays an <strong>in</strong>flammatory role with<strong>in</strong> the human body (Thompson et al., 2004). V.<br />

vulnificus biotype 1 can be lethal <strong>and</strong> biotype 2 can be an opportunistic pathogen to<br />

humans. Biotype 2 is pathogenic <strong>in</strong> Asian <strong>and</strong> European eels. The <strong><strong>pre</strong>valence</strong> <strong>of</strong> this<br />

bacterium is strongly correlated with the water temperature (Feldhusen, 2000).<br />

2.9 Detection <strong>of</strong> virulence genes <strong>of</strong> Vibrio<br />

V. cholerae serogroup non O1 <strong>and</strong> non O139 stra<strong>in</strong>s have not been associated<br />

with epidemics but they can cause sporadic diarrhoea (Chakraborty et al., 2000).<br />

Cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae (O1 <strong>and</strong> O139) exclusively carry<strong>in</strong>g the virulence<br />

factors <strong>of</strong> cholera tox<strong>in</strong> (CT) <strong>and</strong> tox<strong>in</strong>-coregulated pilus (TCP). These factors are<br />

encoded by the ctx <strong>and</strong> tcpA genes (Chakraborty et al., 2000, Srisuk et al., 2010).<br />

Identification <strong>and</strong> detection <strong>of</strong> V. cholerae <strong>and</strong> its virulence is <strong>of</strong>ten achieved by<br />

traditional biochemical methods which was labour <strong>and</strong> time consum<strong>in</strong>g. But some

27<br />

Vibrio spp. display similar biochemical <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>and</strong> it limits the proper<br />

identification <strong>and</strong> characterization <strong>of</strong> Vibrio spp. (Tamrakar et al., 2006). Scientists<br />

have developed PCR based techniques for the detection <strong>of</strong> toxigenic stra<strong>in</strong>s based on<br />

the cholera tox<strong>in</strong> (ctx) gene, <strong>and</strong> the tox<strong>in</strong> coregulated (tcpA) gene (Keasler <strong>and</strong> Hall,<br />

1993, Rivera et al., 2003).<br />

V. parahaemolyticus has been recognized as major pathogenic agent <strong>of</strong><br />

gastroenteritis associated with the consumption <strong>of</strong> seafood (Nishibuchi <strong>and</strong> Kaper,<br />

1995). But not all V. parahaemolyticus stra<strong>in</strong>s are carry<strong>in</strong>g the virulence capacity<br />

(Raghunath et al., 2008). Cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s are categorized <strong>in</strong>to two groups accord<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

their ability <strong>of</strong> haemolys<strong>in</strong>g Wagatsuma blood agar. This is named as Kanagawa<br />

phenomenon (KP). Most <strong>of</strong> the cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus are haemolytic<br />

(KP + ). This haemolys<strong>in</strong> was identified as thermo stable direct haemolys<strong>in</strong> (TDH),<br />

because it was not <strong>in</strong>activated by heat<strong>in</strong>g at 100°C for 10 m<strong>in</strong>. Kanagawa<br />

phenomenon negative stra<strong>in</strong>s were isolated <strong>and</strong> named as TDH-related haemolys<strong>in</strong><br />

(TRH) <strong>and</strong> its activity is lost when heated at 60°C or higher temperature for 10 m<strong>in</strong>.<br />

(Honda <strong>and</strong> Iida, 1993). Cl<strong>in</strong>ical stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus most <strong>of</strong>ten produce<br />

TDH or TRH haemolys<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> carry the gene for tdh <strong>and</strong> trh respectively (Nishibuchi<br />

<strong>and</strong> Kaper, 1995, Raghunath et al., 2008). Both TDH <strong>and</strong> TRH stra<strong>in</strong>s have similar<br />

biological, immunological <strong>and</strong> physiochemical <strong>characteristics</strong> <strong>and</strong> they are composed<br />

<strong>of</strong> 165 am<strong>in</strong>o acids <strong>and</strong> their am<strong>in</strong>o acid sequence homology is about 67% (Honda<br />

<strong>and</strong> Iida, 1993). These data suggested that trh <strong>and</strong> tdh genes probably evolved from a<br />

common ancestor. Researchers identified the tdh gene <strong>in</strong> some stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. mimicus,<br />

V. cholerae non-O1 stra<strong>in</strong>s from the mar<strong>in</strong>e environment <strong>and</strong> occasionally from<br />

diarrhoea samples while all the stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. hollisae were positive for tdh gene<br />

(Honda <strong>and</strong> Iida, 1993, Nishibuchi <strong>and</strong> Kaper, 1995).<br />

Identification <strong>of</strong> virulent stra<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> V. parahaemolyticus has been done with<br />

the conventional methods, such as detection <strong>of</strong> haemolys<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> Wagatsuma agar<br />

conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g washed human or rabbit erythrocytes, immunological methods (reverse<br />

passive haemagglut<strong>in</strong>ation, ELISA) (Honda <strong>and</strong> Iida, 1993). But for the detection <strong>of</strong><br />

TRH there are no available commercial methods. Therefore identification <strong>of</strong> virulence

28<br />

genes by DNA based <strong>molecular</strong> techniques such as PCR <strong>and</strong> colony hybridization<br />

methods are more important. Researchers found the PCR method as a more reliable,<br />

rapid <strong>and</strong> sensitive method compare to conventional microbiological assays (Bej et<br />

al., 1999, Raghunath et al., 2008).<br />

2.10 Prevention <strong>and</strong> control <strong>of</strong> Vibrio <strong>in</strong> shrimp production cha<strong>in</strong><br />

2.10.1 Pre harvest stage<br />

2.10.1.1 Biosecurity measures<br />

With an exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g aquaculture <strong>in</strong>dustry, appropriate techniques are required to<br />

mitigate diseases. With new technologies, biosecurity measures can easily be adapted<br />

for small or large scales farms. Biosecurity is def<strong>in</strong>ed as the practices that reduce the<br />

probability <strong>of</strong> pathogen <strong>in</strong>troduction <strong>and</strong> control the subsequent s<strong>pre</strong>ad from one place<br />

to another. The primary goal <strong>of</strong> biosecurity <strong>in</strong> shrimp farm<strong>in</strong>g is to <strong>pre</strong>vent entry <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong>fectious organisms <strong>in</strong>to the farm. Possible carriers are, (i) <strong>in</strong>fected host (post larvae,<br />

brood stock); (ii) non-host biological carriers (contam<strong>in</strong>ated water); (iii) <strong>in</strong>animate<br />

objects contam<strong>in</strong>ated with pathogens (vehicles, human, nets) (Lotz, 1997). A sound<br />

biosecurity program <strong>of</strong> a shrimp farm <strong>in</strong>cludes disease <strong>pre</strong>vention, disease monitor<strong>in</strong>g,<br />

management <strong>of</strong> disease outbreak, clean<strong>in</strong>g, dis<strong>in</strong>fection <strong>and</strong> general security<br />

<strong>pre</strong>ventions.<br />

Perera et al. (2008) recommended measures can be taken to m<strong>in</strong>imize the<br />

<strong>in</strong>put <strong>of</strong> pathogens <strong>in</strong>to the farm. For example, stocks (brood<strong>in</strong>g/post larvae) can be<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed from populations <strong>of</strong> specific pathogen free or specific pathogen resistance<br />

stock or populations subject to monitor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> known to be <strong>in</strong> good health, or<br />

quarant<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> tested or treated to reduce the risk. Pathogen transmission by feed can<br />

be controlled by provid<strong>in</strong>g commercial pelletized feed that are subjected to a degree<br />

<strong>of</strong> pathogen <strong>in</strong>activation by heat generated through the process <strong>of</strong> extrusion <strong>and</strong> pellet<br />

dry<strong>in</strong>g (Perera et al., 2008). Water is the major non-liv<strong>in</strong>g conveyer <strong>of</strong> the pathogens.<br />

Pathogens may be <strong>pre</strong>sent <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>com<strong>in</strong>g water because <strong>of</strong> the <strong>pre</strong>sence <strong>of</strong> natural

29<br />

host <strong>and</strong> effluent from the contam<strong>in</strong>ated farms (Lotz, 1997). Intake water can be<br />

purified by screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> filter<strong>in</strong>g to reduce the formites <strong>and</strong> carrier organisms. Risk<br />

associated with water can be reduced by application <strong>of</strong> UV, ozone or chemicals before<br />

use (Perera et al., 2008). A study found that application <strong>of</strong> alternat<strong>in</strong>g low-amperage<br />

electric treatments to effluent sea water to <strong>in</strong>activate the V. parahaemolyticus while<br />

generat<strong>in</strong>g only low levels <strong>of</strong> chlor<strong>in</strong>e (Park et al., 2004). This method was able to<br />

overcome the problem <strong>of</strong> chlor<strong>in</strong>e generation that usually results from treatment with<br />

cont<strong>in</strong>uous direct current. Farm equipment, such as aeration, harvest nets, conta<strong>in</strong>ers,<br />

foot wear <strong>and</strong> vehicles need to be dis<strong>in</strong>fected us<strong>in</strong>g suitable dis<strong>in</strong>fectants such as<br />

sodium hypochlorite, iodophors <strong>and</strong> sodium chloride. Periodically test<strong>in</strong>g for the<br />

specific diseases can carried out for the early detection <strong>and</strong> quick response <strong>and</strong><br />

<strong>pre</strong>vention <strong>of</strong> disease outbreaks. Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> farm staff is essential for awareness <strong>of</strong><br />

the potential risks <strong>and</strong> biological pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong> biosecurity measures (Perera et al.,<br />

2008).<br />

In Sri Lanka, biosecurity measures are monitored by the National Aquaculture<br />

Development Authority (NAQDA). Screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> brood stock for white spot disease is<br />

carried out before be<strong>in</strong>g issued to the farmers. If the farm is <strong>in</strong>fected with a disease,<br />

<strong>of</strong>ficers <strong>in</strong>form farmers to harvest non-<strong>in</strong>fected farms us<strong>in</strong>g nets, after that affected<br />

farms dis<strong>in</strong>fected us<strong>in</strong>g pesticides to destroy the <strong>in</strong>fected shrimps. Water is released<br />

after 4-7 days <strong>in</strong> to the sediment areas (Weerakoon, 2007). Sometimes the agency<br />

delays the restock<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the post larvae for the next crop <strong>in</strong> affected zone. Even<br />

though farmers ga<strong>in</strong> knowledge on biosecurity, economic issues restrict the farmer’s<br />

ability or will<strong>in</strong>gness to <strong>in</strong>vest <strong>in</strong> biosecurity (Munas<strong>in</strong>ghe et al., 2010).<br />

2.10.1.2 Application <strong>of</strong> probiotics<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> probiotics is widely <strong>pre</strong>valent <strong>in</strong> the aquaculture, especially <strong>in</strong><br />

shrimp culture as a means <strong>of</strong> controll<strong>in</strong>g diseases <strong>and</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g water quality without<br />

the use <strong>of</strong> antibiotics <strong>and</strong> dis<strong>in</strong>fectants (Ma et al., 2009). A probiotic is def<strong>in</strong>ed as a<br />

live microbial agent that <strong>pre</strong>vents pathogens from proliferat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>test<strong>in</strong>al tract,<br />

on the superficial structures <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> the cultural environment <strong>of</strong> <strong>species</strong> <strong>and</strong> that aid

30<br />

digestion, improves water quality, or stimulate the immune system <strong>of</strong> the host<br />

(Verschuere et al., 2000). Microorganism belong<strong>in</strong>g to photosynthetic bacteria,<br />

Nitromonas spp., Lactobacillus spp., yeast, Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas fluorescens,<br />

Streptococcus faecium, Tetraselmis succia <strong>and</strong> other bacteria have been tested as<br />

probiotics (Wang et al., 2005).<br />

Several studies have been carried out to determ<strong>in</strong>e the effectiveness <strong>of</strong><br />

probiotics on aquaculture. Rengpipat et al. (1998) reported the use <strong>of</strong> Bacillus stra<strong>in</strong><br />

S11 as a probiotic <strong>in</strong> black tiger (P. monodon) shrimp culture. After a 100 day feed<strong>in</strong>g<br />

trial with probiotic supplements <strong>and</strong> non-supplement feed, P. monodon challenged<br />

with pathogenic V. harveyi stra<strong>in</strong> D331 by immers<strong>in</strong>g the shrimp. Ten days later, all<br />

the shrimp groups treated with probiotics showed 100% survival <strong>and</strong> the control<br />

group had 26% survival (Rengpipat et al., 1998). Similar research was carried out <strong>in</strong><br />

shrimp ponds <strong>in</strong> the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es where the losses due to lum<strong>in</strong>as Vibrio (V. harveyi)<br />

are catastrophic. Bacillus spp. used as probiotics <strong>and</strong> experienced a higher survival<br />

rate (80-100%) <strong>in</strong> treated farms (Moriarty, 1999). Investigations carried out to<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e the effectiveness <strong>of</strong> probiotics on white shrimp (P. vannamei) found a<br />

noticeable <strong>in</strong>fluence on the shrimp production <strong>and</strong> an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the water quality by<br />

reduc<strong>in</strong>g concentration <strong>of</strong> nitrogen <strong>and</strong> phosphorous. A study found that the average<br />