The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

The Syntax of Givenness Ivona Kucerová

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

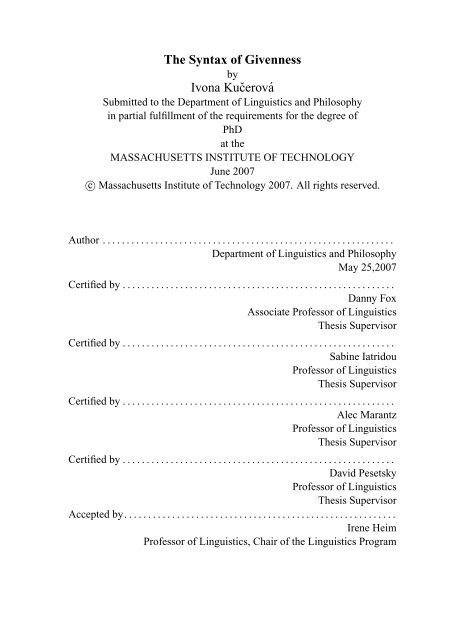

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Syntax</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Givenness</strong><br />

by<br />

<strong>Ivona</strong> Kučerová<br />

Submitted to the Department <strong>of</strong> Linguistics and Philosophy<br />

in partial fulfillment <strong>of</strong> the requirements for the degree <strong>of</strong><br />

PhD<br />

at the<br />

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY<br />

June 2007<br />

c○ Massachusetts Institute <strong>of</strong> Technology 2007. All rights reserved.<br />

Author . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Linguistics and Philosophy<br />

May 25,2007<br />

Certified by . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

Danny Fox<br />

Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor<br />

Certified by . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

Sabine Iatridou<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor<br />

Certified by . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

Alec Marantz<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor<br />

Certified by . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

David Pesetsky<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor<br />

Accepted by. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .<br />

Irene Heim<br />

Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics, Chair <strong>of</strong> the Linguistics Program

Abstract<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Syntax</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Givenness</strong><br />

by<br />

<strong>Ivona</strong> Kučerová<br />

Submitted to the Department <strong>of</strong> Linguistics and Philosophy<br />

on May 25,2007, in partial fulfillment <strong>of</strong> the<br />

requirements for the degree <strong>of</strong><br />

PhD<br />

<strong>The</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> this thesis is to account for distributional patterns <strong>of</strong> given and new items in<br />

Czech, especially their word order. <strong>The</strong> system proposed here has four basic components:<br />

(i) syntax, (ii) economy, (iii) interpretation, and (iv) reference set computation. <strong>The</strong> approach<br />

belongs to the family <strong>of</strong> interface driven approaches.<br />

<strong>The</strong> syntactic part <strong>of</strong> the thesis introduces a free syntactic movement (G-movement).<br />

<strong>The</strong> movement causes very local reordering <strong>of</strong> given elements with respect to new elements<br />

in the structure. G-movement is licensed only if it creates a syntactic structure which leads<br />

to a semantic interpretation that would not otherwise be available. <strong>The</strong> economy condition<br />

interacts with the way givenness is interpreted. I introduce a recursive operator that adds<br />

a presupposition to given elements. <strong>The</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> the operator is regulated by the<br />

Maximize presupposition maxim <strong>of</strong> Heim (1991). <strong>The</strong> reference set for purposes <strong>of</strong> this<br />

evaluation is defined as the set <strong>of</strong> derivations that have the same numeration and the same<br />

assertion.<br />

Finally, I argue that the licensing semantic conditions on givenness in Czech are not<br />

identical to the licensing conditions on deaccenting in English. <strong>The</strong> givenness licensing<br />

conditions are stronger in that they require that for an element to be given it must not only<br />

have a salient antecedent but also satisfy an existential presupposition.<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor: Danny Fox<br />

Title: Associate Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor: Sabine Iatridou<br />

Title: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor: Alec Marantz<br />

Title: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

<strong>The</strong>sis Supervisor: David Pesetsky<br />

Title: Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Linguistics<br />

2

Acknowledgments<br />

Two things were difficult about writing my thesis: (i) choosing the topic (there were too<br />

many things I would like to write a thesis about) and (ii) choosing an adviser. <strong>The</strong>re were<br />

several people I wanted to have as my adviser. In the end I decided to write my thesis on<br />

four different topics and to have four advisers. <strong>The</strong> first decision turned out to be untenable<br />

and I ended up dropping three <strong>of</strong> the topics. <strong>The</strong> second decision, on the other hand, paid<br />

<strong>of</strong>f; except for typographical issues while trying to typeset the cover page <strong>of</strong> my thesis I<br />

have never regretted it.<br />

Alec, Danny, David and Sabine (in alphabetical order) are more than wonderful scholars.<br />

<strong>The</strong>y have been my mentors and guides without ever telling me what to do. In a sense,<br />

they are coauthors <strong>of</strong> many ideas in my thesis: most <strong>of</strong> the ideas took their shape while<br />

sitting together for hours, playing with puzzles and trying different ways to attack them. I<br />

have really enjoyed the eight months I have spent writing my thesis.<br />

My stay at MIT was <strong>of</strong> course more than my dissertation. It is impossible to thank all the<br />

people I have met here and whom I have learned from. Among my teachers a special place<br />

belongs to Noam Chomsky, Mike Collins, Morris Halle, Irene Heim and Donca Steriade. I<br />

want to thank them here for their time and interest in my work.<br />

Sometimes it is hard to draw a clear line between a friend and a colleague. Many people<br />

were both. Asaf Bachrach, Roni Katzir and Raj Singh became my ‘classmates’ and<br />

provided me with intense underground education and great food. Brooke Cowan, Svea<br />

Heinemann and Sarah Hulsey made sure I would know that life at MIT is more than linguistics.<br />

Special thanks go to Béd’a Jelínek without whom I would have never applied to MIT.<br />

He knows best that there is more I should thank him for.<br />

I want to thank also my former teachers without whom I would have not even thought<br />

about starting a PhD: Vlasta Dvořáková, Jindřich Rosenkranz, Jaroslava Janáčková, Michael<br />

Špirit, Jiří Homoláč and †Alexander Stich (in chronological order).<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is no way I could thank my parents and Roni Katzir without trivializing their<br />

place in my life.<br />

3

Contents<br />

1 To Be Given 6<br />

1.1 G-movement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<br />

1.2 Basic word order and Focus projection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17<br />

1.3 Verb partitions and their semantic ambiguity . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22<br />

1.4 <strong>The</strong> boundedness <strong>of</strong> G-movement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26<br />

1.5 <strong>The</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> pronouns: G-movement as a last Resort . . . . . . . . . 34<br />

1.6 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40<br />

2 G-movement 41<br />

2.1 <strong>The</strong> target <strong>of</strong> G-movement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42<br />

2.2 When in the derivation does G-movement apply? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45<br />

2.3 <strong>The</strong> head movement restriction on G-movement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56<br />

2.4 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63<br />

3 Complex Word Order Patterns 64<br />

3.1 Deriving the verb partition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65<br />

3.2 Multiple G-movement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70<br />

3.3 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84<br />

4 Semantic Interpretation 86<br />

4.1 Where we stand . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 87<br />

4.2 Marking givenness by an operator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93<br />

4.2.1 G-movement domains are propositional domains . . . . . . . . . . 94<br />

4.2.2 <strong>The</strong> G-operator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98<br />

4.3 <strong>The</strong> evaluation component . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109<br />

4.4 <strong>The</strong> G-operator and coordination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114<br />

4.5 <strong>The</strong> interpretation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Givenness</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120<br />

4.6 <strong>Givenness</strong> versus deaccentuation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123<br />

4.7 A note on phonology and its relation to givenness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128<br />

4.8 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132<br />

A G-movement is A-movement 133<br />

A.1 Condition A . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134<br />

A.2 Condition C . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136<br />

A.3 <strong>The</strong> Weak Cross-Over Effect . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139<br />

4

A.4 A note on base generation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 139<br />

A.5 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141<br />

5

Chapter 1<br />

To Be Given<br />

Consider the Czech sentences in (1). 1,2<br />

(1) a. SVO: Chlapec našel lízátko.<br />

boy.Nom found lollipop.Acc<br />

b. OVS: Lízátko našel chlapec.<br />

lollipop.Acc found boy.Nom<br />

c. SOV: Chlapec lízátko NAŠEL.<br />

boy.Nom lollipop.Acc found<br />

d. OSV: LÍZÁtko chlapec našel.<br />

lollipop.Acc boy.Nom found<br />

<strong>The</strong> sentences in (1) describe a similar situation. In each <strong>of</strong> them the speaker asserts that<br />

there was a time interval in the past such that an event <strong>of</strong> finding took place in that interval.<br />

Furthermore, we learn that the event <strong>of</strong> finding had two participants (a finder and a findee)<br />

and we also learn who these participants were (some boy and a lollipop). <strong>The</strong> sentences in<br />

(1) nevertherless differ in their meaning and in the set <strong>of</strong> contexts in which they are felicitous.<br />

To see this, let’s first concentrate on the first two orders, i.e., the SVO and the OVS<br />

orders. Corresponding English translations <strong>of</strong> the Czech sentences are given in (2). 3<br />

1 Capital letters here and throughout the text stand for a contrastively stressed syllable.<br />

2 <strong>The</strong> four combinations given in (1) are the only combinations that can be used as declarative clauses. <strong>The</strong><br />

remaining permutations, given in (i) and (ii), are grammatical but only as questions. <strong>The</strong> following chapters<br />

will deal with declarative clauses only.<br />

(i)<br />

(ii)<br />

VSO: Našel chlapec lízátko?<br />

found boy.Nom lollipop.Acc<br />

‘Did the boy found the lollipop?’<br />

VOS: Našel lízátko chlapec?<br />

found lollipop.Acc boy.Nom<br />

‘Was it the lollipop what the boy found?’<br />

3 <strong>The</strong> hash sign # stands for an utterance that is not felicitous in the given context. In this particular case,<br />

it stands for an infelicitous translation.<br />

6

(2) a. SVO: Chlapec našel lízátko.<br />

boy.Nom found lollipop.Acc<br />

(i) ‘A boy found a lollipop.’<br />

(ii) ‘<strong>The</strong> boy found a lollipop.’<br />

(iii) ‘<strong>The</strong> boy found the lollipop.’<br />

(iv) #‘A boy found the lollipop.’<br />

b. OVS: Lízátko našel chlapec.<br />

lollipop.Acc found boy.Nom<br />

‘A boy found the lollipop.’<br />

As we can see in (2-a), the SVO order in Czech is compatible with several different interpretations.<br />

<strong>The</strong> very same Czech string can correspond (i) to a situation where neither a boy,<br />

nor a lollipop are given, in the sense that there is no referent determined by the previous<br />

context, i.e., the existence <strong>of</strong> the referent has not been asserted yet; (ii) to a situation where<br />

only a boy has been previously determined by the context; or (iii) to a situation where both<br />

the boy and the lollipop have a unique referent but they have not been introduced by the<br />

previous context. Crucially, however, the SVO order is not felicitous in a situation in which<br />

only the lollipop has been introduced by the previous context, (iv).<br />

To achieve the missing interpretation, i.e., the interpretation in which only the object<br />

has been determined by the previous context, the word order must be OVS, as in (2-b),<br />

translated as ‘A boy found the lollipop.’.<br />

What is the nature <strong>of</strong> the reordering? Notice that in order to capture the intuition about<br />

meaning differences corresponding to different word orders, I used indefinite and definite<br />

articles. Since Czech does not have any overt morphological marking <strong>of</strong> definiteness – with<br />

the exception <strong>of</strong> demonstrative and deictic pronouns – we could understand the different<br />

word orders as a strategy to achieve the same interpretation that English can achieve by<br />

using overt determiners. This would be, however, a simplification. <strong>The</strong> object in the OVS<br />

order does not need to correspond to a definite description. It is enough that it has been<br />

introduced in the previous discourse, as in (3). 4<br />

(3) a. We left some cookies and lollipops in the garden for the kids. Who found a<br />

lollipop?<br />

b. Lízátko našla Maruška a Janička.<br />

lollipop.Acc found Maruška and Janička<br />

‘Little Mary and little Jane found a lollipop.’<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> reordering observed in (2-a) and (2-b) might remind the reader <strong>of</strong> the Mapping Hypothesis <strong>of</strong> Diesing<br />

1992 or <strong>of</strong> a more general discussion <strong>of</strong> specificity as in Enç 1991; van Geenhoven 1998; Farkas 2002, among<br />

many others. One might think that for a DP to become specific (whatever it means) such a DP must move to<br />

(or it must be base-generated in) a certain syntactic position. As we will see shortly, not only referential, but<br />

also predicational or propositional elements can be introduced in a discourse in the same way as the object in<br />

(2-b). I do not know at this point whether there is any connection between specificity and the data discussed<br />

here. In general, I will ignore possible relations between quantification and information structure here.<br />

7

We will see in chapter 4, however, that the correlation with definite articles is not accidental.<br />

I will argue that the purpose <strong>of</strong> both reordering for givenness and definiteness marking<br />

is to maximize presupposition (Heim, 1991). While the two strategies are in principle different,<br />

their realization may sometimes be identical.<br />

I thus argue that the nature <strong>of</strong> the reordering found in (2-b) is indeed to mark that<br />

something has already been introduced in the discourse. An interesting fact to observe<br />

is that even though the SVO order has multiple interpretations, certain interpretations are<br />

excluded and they can be achieved only by reordering. This suggests that the purpose <strong>of</strong><br />

the reordering is to achieve an interpretation that would not be available otherwise. 5<br />

I will argue shortly that this ordering correlates with a requirement that given (old, presupposed)<br />

elements linearly precede elements that are new (asserted, non-presupposed) in<br />

the discourse. While in (2-a) this requirement can be satisfied within the SVO order, in<br />

case <strong>of</strong> the (2-b) examples, reordering is needed.<br />

<strong>The</strong> examples in (1-c) and (1-d), repeated below as (4-a) and (4-b), are rather different.<br />

While in the examples in (2-a) and (2-b) at least one participant has not been introduced in<br />

the discourse yet, the examples in (4-a) and (4-b) contain only previously introduced participants.<br />

In other words, the utterances in (2-a) and (2-b) correspond to an assertion that<br />

combines something already presupposed with something that has not been presupposed<br />

yet. In contrast, the utterance in (1-c)–(1-d) operates on an already asserted proposition.<br />

<strong>The</strong> meaning <strong>of</strong> the SOV order in (4-a) can be either verification <strong>of</strong> the true value <strong>of</strong> the<br />

proposition, or correction <strong>of</strong> a part <strong>of</strong> the proposition by excluding other alternatives. 6<br />

Similarly, the example in (4-b) corresponds to an utterance about already introduced participants<br />

and it comments on their relation (contrastive topic or topic).<br />

(4) a. SOV: <strong>The</strong> boy did find the lollipop. (He did not steal it.)<br />

b. OSV: As for the lollipop, the boy found it (but as for the chocolate, he got it<br />

from his mother).<br />

<strong>The</strong> study presented here concerns mainly the type <strong>of</strong> examples given in (2). Before I<br />

undertake a closer investigation <strong>of</strong> these cases I want to provide the reader with some further<br />

observations that will help to clarify why it is useful to treat the examples in (2) as separate<br />

from the examples in (4). We have already seen that the type <strong>of</strong> reordering witnessed in<br />

(2) may teach us something about the way presupposed and non-presupposed elements are<br />

marked in a language that does not have overt articles. Everything being equal, the English<br />

translations <strong>of</strong> the Czech examples in (2) differ only in the use <strong>of</strong> articles. <strong>The</strong>re are no<br />

other obvious changes in syntax, prosody or morphology. <strong>The</strong> English translations <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Czech examples in (4) are very different in this respect. Both have marked prosody (pitch<br />

5 We will see in this chapter and especially in section 1.2 that SVO is the basic word order in Czech. I will<br />

argue that a basic word order in general allows more flexibility in interpretation than a derived word order.<br />

6 In literature on information structure, this type <strong>of</strong> construction is <strong>of</strong>ten referred to as verum focus, i.e.,<br />

a construction where the speaker verifies or denies that an already presupposed proposition is true, or contrastive<br />

focus or correction, in case the speaker asserts an exclusion <strong>of</strong> an alternative that might have been<br />

introduced by the previous context.<br />

8

accent on the auxiliary did in (4-a) and pitch accent on the lollipop in (4-b), both followed<br />

by optional deaccenting). Furthermore, the example in (4-a) contains additional morphological<br />

material (did) and the example in (4-b) may correspond in English to a cleft, i.e., to<br />

a rather complex structure. I suggest that Czech is like English in that the processes that<br />

lead to the reordering in Czech (2-b) are <strong>of</strong> a very different nature than the processes that<br />

lead to the reorderings witnessed in Czech (4). If we want to understand these processes<br />

we should study them separately. 7<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is another parallel between Czech and English worth mentioning. It concerns<br />

differences between the prosodic properties <strong>of</strong> (2) and (4). As in English, the Czech intonation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the examples in (2) is neutral. Furthermore, there are no relevant differences<br />

between (1-a) and (1-b). Compare figure 1-1 and 1-2. In contrast, the intonation <strong>of</strong> (4) is<br />

marked. In (4-a), the verb našel ‘found’ is distinct in its duration and intensity. As we can<br />

see in figure 1-3, the duration <strong>of</strong> the bisyllabic verb is roughly doubled in comparison with<br />

the pronunciation <strong>of</strong> the same word in other syntactic environments. In (4-b), the sentence<br />

initial object lízátko ‘lollipop’ is pronounced with a higher tone and the sequence is followed<br />

by deaccenting and an optional intonational break, as in figure 1-4.<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

Pitch (Hz)<br />

100<br />

0<br />

chlapec nasel lizatko<br />

0 2.83288<br />

Time (s)<br />

Figure 1-1: SVO order<br />

7 Reordering processes, superficially similar to those seen in (2) and (4), are <strong>of</strong>ten referred to as scrambling.<br />

<strong>The</strong> term originated in Ross 1967 as a term for stylistic reordering. In the more recent literature,<br />

scrambling may refer to A-movement, A-bar movement or base generation (for example, Williams 1984;<br />

Saito 1989; Webelhuth 1989; Grewendorf and Sternfeld 1990; Mahajan 1990; Lasnik and Saito 1992; Saito<br />

1992; Corver and van Riemsdijk 1994; Miyagawa 1997; Bošković and Takahashi 1998; Bailyn 2001; Karimi<br />

2003; Sabel and Saito 2005). I will avoid the term scrambling here in order to minimize possible confusion<br />

that might come from various interpretations the term has been assigned in the literature.<br />

9

Pitch (Hz)<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

lizatko nasel chlapec<br />

0 3.32218<br />

Time (s)<br />

Figure 1-2: OVS order<br />

Before we get to the actual proposal there is another empirical observation to be established.<br />

Notice that in the examples in (2) the verb occupies the second position. In contrast,<br />

in the examples in (4) the verb linearly follows the arguments. 8 As we will see shortly, two<br />

factors turn out to be crucial for understanding Czech word order variations: the relative<br />

position <strong>of</strong> arguments and the relative position <strong>of</strong> the verb with respect to the arguments.<br />

In the rest <strong>of</strong> this chapter and in the following chapters I will closely investigate the<br />

nature <strong>of</strong> the reordering witnessed in (2). I will argue that this type <strong>of</strong> reordering is derived<br />

by short A-movement that is sometimes parasitic on verb head movement. I will call this<br />

movement G-Movement. This movement happens, I will claim, only in order to derive a<br />

semantic interpretation that would not be available otherwise. As such this kind <strong>of</strong> movement<br />

is driven by interpretation requirements and is restricted by economy.<br />

<strong>The</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> section 1.1 is to introduce the basics <strong>of</strong> a system that can account for the<br />

Czech word order data observed in (2). I will present the proposal in stages.<br />

<strong>The</strong> first version <strong>of</strong> the system, introduced in this section, is designed to account for<br />

the order <strong>of</strong> the arguments and the position <strong>of</strong> the verb. Further refinements will be introduced<br />

in the following chapters. In the next section, section 1.2, I will address the question<br />

<strong>of</strong> how come multiple interpretations are available (only) for basic word orders, such as<br />

SVO. In particular, I will argue that the ambiguity follows from G-movement being a last<br />

resort operation. Section 1.3 will more closely investigate the fact that the verb intervenes<br />

between the two arguments, in contrast to other types <strong>of</strong> reorderings, such as questions<br />

8 To make the picture complete, in questions the verb precedes the arguments.<br />

10

Pitch (Hz)<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

100<br />

0<br />

chlapec lizatko nasel<br />

0 3.39374<br />

Time (s)<br />

Figure 1-3: SOV order<br />

500<br />

400<br />

300<br />

200<br />

Pitch (Hz)<br />

100<br />

0<br />

lizatko chlapec nasel<br />

0 3.18576<br />

Time (s)<br />

Figure 1-4: OSV order<br />

11

and contrastive foci readings. I will argue that even though G-movement is independently<br />

restricted by syntax like any other type <strong>of</strong> movement, it differs from other types <strong>of</strong> movement<br />

in that it is parasitic on head movement. <strong>The</strong> emergence <strong>of</strong> verb second will be seen<br />

as a consequence <strong>of</strong> this restriction. In section 1.4 I will explore further consequences <strong>of</strong><br />

this restriction, namely, differences in locality restrictions on G-movement dependent on<br />

head movement properties <strong>of</strong> the relevant head. In the last section <strong>of</strong> this chapter, 1.5, I<br />

will provide independent evidence for the proposed machinery. I will argue based on the<br />

distribution <strong>of</strong> pronouns that G-movement is a last resort operation. As such it takes place<br />

only if the relevant interpretation would not otherwise be available.<br />

1.1 G-movement<br />

<strong>The</strong> idea that word order in a language such as Czech is sensitive to the discourse in the<br />

sense that parts <strong>of</strong> a clause that are old (given, in the background etc.) linearly precede the<br />

elements that are new in the discourse has been investigated in Czech linguistics for a long<br />

time. 9<br />

<strong>The</strong> questions that have not, to my knowledge, been successfully addressed yet are (i)<br />

how exactly is the linear partition (i.e., given ≻ new) derived, and (ii) how is the word order<br />

within the old and the new part determined.<br />

Consider the example in (5). This sentence could be an answer to ‘What did Petr do<br />

yesterday with his car?’ <strong>The</strong> || sign corresponds to the partition between given and new.<br />

Now compare (5) and (6). <strong>The</strong> example in (6) shows the basic word order and as such it is<br />

a suitable answer to the question ‘What happened?’. 10 As we can see schematized in (7),<br />

the two word orders differ quite radically.<br />

(5) Petr auto včera || řídil rychle.<br />

Petr.Nom car.Acc yesterday drove fast<br />

‘Yesterday Petr drove his car fast.’<br />

←− S O Adv1 V Adv2<br />

9 <strong>The</strong> relevance <strong>of</strong> the discourse for word order has already been observed by traditional grammarians (for<br />

example, Gebauer 1900). In the pre-modern tradition, the observation was stated in terms <strong>of</strong> psychological<br />

and structural subjects. To my knowledge, the intuition about the broader relevance <strong>of</strong> the discourse was<br />

for the first time formalized in a more systematic way by Vilém Mathesius in Mathesius [1929] 1983 and<br />

Mathesius 1939 (the first version <strong>of</strong> the paper was presented in Prague in 1908). In order to describe the<br />

relation between word order and the discourse, Mathesius introduced the term aktuální členění. This term is<br />

usually translated as topic focus articulation. This is not an exact translation though. <strong>The</strong> literal translation<br />

would be something like structuring [<strong>of</strong> the sentence] dependent on the current context and referred to theme<br />

versus rheme distinction. Authors that further developed the notion <strong>of</strong> word order dependence on the current<br />

context include, for example, Daneš 1954, 1957, 1974; Novák 1959; ; Dokulil and Daneš 1958; Šmilauer<br />

1960; Adamec 1962; Firbas 1964; Hausenblas 1964; Sgall 1967; Benešová 1968; Hajičová 1973, 1974; Sgall<br />

et al. 1980, 1986; Hajičová et al. 1998, among many others. <strong>The</strong>re is no way I can acknowledge in this study<br />

all <strong>of</strong> the empirical observations, generalizations and linguistic insight that is present in the previous work on<br />

aktuální členění in Czech.<br />

10 I will provide diagnostics for determining basic word order in 1.2.<br />

12

(6) Petr řídil včera rychle auto.<br />

Petr.Nom drove yesterday fast car.Acc<br />

‘Yesterday Petr drove fast his car.’<br />

←− S V Adv1 Adv2 O<br />

(7) Petr drove yesterday fast car −→ Petr car yesterday || drove fast<br />

<strong>The</strong>re are two facts to be noticed. (i) <strong>The</strong> given elements in (5) precede the new elements.<br />

(ii) While the relative order <strong>of</strong> the new items in (5) is preserved relative to (6), the relative<br />

order <strong>of</strong> the given items has changed. <strong>The</strong> changes are highlighted in (8) and (9).<br />

(8) Word order <strong>of</strong> the given elements:<br />

a. Basic: Petr drove yesterday fast car<br />

b. Derived: Petr car yesterday || drove fast<br />

(9) Word order <strong>of</strong> the new elements:<br />

a. Basic: Petr drove yesterday fast car<br />

b. Derived: Petr car yesterday || drove fast<br />

As we will see throughout the coming sections and chapters, this is a typical pattern<br />

that arises in other places as well: <strong>The</strong> relative order <strong>of</strong> given items with respect to the<br />

basic word order may undergo various permutations, while the relative order <strong>of</strong> new items<br />

usually stays unchanged. <strong>The</strong> only exception is in fact a new finite verb, as we will see<br />

shortly. In all other cases, new items do not change their relative order at all. As we will<br />

see later in this section, this observation is important and it will become crucial for the<br />

way we are going to account for different Czech word order patterns. As we will see, reorderings<br />

happen in a principled way and they can be directly predicted from the relevant<br />

syntactic structure.<br />

Another important fact is that the relative order <strong>of</strong> given items only sometimes changes.<br />

As we can see in (8), the relative order <strong>of</strong> the subject Petr with respect to ‘car’ and ‘yesterday’<br />

does not change. In contrast, the order <strong>of</strong> the object auto ‘car’ and the adverbial včera<br />

‘yesterday’ is reversed. For example, in the same sentence without the adverb ‘yesterday’,<br />

the relative word order <strong>of</strong> the given items would be the same, (10).<br />

(10) Petr auto || řídil rychle.<br />

Petr.Nom car.Acc drove fast<br />

‘Petr drove his car fast.’<br />

I propose that these word order facts suggest that only given elements move for information<br />

structure purposes. This is a simplistic picture because new finite verbs sometimes move<br />

as well but let’s stay with the simple generalization for the sake <strong>of</strong> building the proposal in<br />

stages.<br />

13

Notice that there is no optionality in the word order <strong>of</strong> given elements in a sentence<br />

with a particular meaning. Thus, we need to have a restrictive syntactic system that would<br />

account for the word order. I argue that given elements undergo a special kind <strong>of</strong> movement<br />

that I will call G-movement. <strong>The</strong> rules governing G-movement are given in (11). Further<br />

restrictions on G-movement are stated in (12).<br />

(11) G-Movement [version 1]<br />

G-movement must take place<br />

a. iff α G is asymmetrically c-commanded by a non-G element,<br />

b. unless the movement is independently blocked.<br />

(12) Restrictions on G-movement:<br />

G-movement is restricted as follows:<br />

a. α G moves to the closest position X, such that no non-G element asymmetrically<br />

c-commands α G .<br />

b. If α is XP, then α moves to an XP position.<br />

c. If α is a head, then α moves to an X 0 position.<br />

(13) Closeness: (after Rizzi (1990))<br />

X is the closest to Y only if there is no Z such that Z c-commands Y and does not<br />

c-command X.<br />

Following Reinhart 1997, 2006; Fox 1995, 2000, I argue that G-movement is a syntactic<br />

operation that takes place only if it affects one or both <strong>of</strong> the interfaces. In particular, I<br />

argue that G-movement must have semantic import. In other words, the grammar I argue<br />

for is restricted by economy in that it allows only syntactic operations that lead to a<br />

distinct semantic interpretation. Notice that if there is no non-G element asymmetrically<br />

c-commanding α G the closest position that satisfies the requirement on G-movement is the<br />

position <strong>of</strong> α G itself. Thus, if there is no structurally higher new element, α G does not<br />

move.<br />

<strong>The</strong> definition <strong>of</strong> G-movement implies that an element does not enter the computation<br />

marked as given but it is only the result <strong>of</strong> the computation that the element is interpreted as<br />

such. As we will see in 1.5, this property is crucially connected to the fact that G-movement<br />

is a last resort operation.<br />

Furthermore, (11) crucially relies on the notion <strong>of</strong> asymmetrical c-command (Kayne,<br />

1994) 11 and it does not distinguish heads from phrases, in the sense that both heads and<br />

11 <strong>The</strong> relevant definitions are given below:<br />

(i) X asymmetrically c-commands Y iff X c-commands Y and Y does not c-command X. (Kayne, 1994,<br />

p. 4, (2))<br />

(ii)<br />

X c-commands Y iff X and Y are categories and X excludes Y and every category that dominates X<br />

dominates Y. (Kayne, 1994, p. 16, (3))<br />

(iii) In the sense <strong>of</strong> Chomsky 1986, p. 9: X excludes Y if no segment <strong>of</strong> X dominates Y. (Kayne, 1994, p.<br />

133, ftn.1)<br />

14

phrases are required to undergo G-movement. 12 Consider the trees in (14).<br />

Taking into account that Czech is an SVO language, there are two basic cases to consider.<br />

Either (i) α G is a head and β (a non-G element) is a phrase, as in (14-a); or (ii) α G is<br />

a phrase and β is a head, as in (14-b).<br />

(14) a.<br />

βP α G<br />

b.<br />

β<br />

α G P<br />

In case <strong>of</strong> (14-a), the definition <strong>of</strong> G-movement requires the head α G to move above<br />

the phrase, resulting in (15). I leave open for now what exactly the landing site <strong>of</strong> such a<br />

movement is. I will address this question in section 2.3.<br />

(15)<br />

α G<br />

βP t αG<br />

An example <strong>of</strong> such movement is found in unergatives. In Czech, in the basic word<br />

order an unergative subject precedes an unergative verb, as in (16). If the verb is given and<br />

the subject is new, the word order is reversed, as in (17). 13<br />

(16) a. What happened?<br />

b. Marie tancovala.<br />

Marie danced<br />

(17) a. Who danced?<br />

b. Tancovala || Marie.<br />

danced Marie<br />

‘Marie danced.’<br />

In case <strong>of</strong> (14-b), the definition <strong>of</strong> G-movement requires the phrase α G to move over the<br />

head β, resulting into (18).<br />

(18)<br />

α G P β tαG<br />

A simple case <strong>of</strong> such movement can be found with unaccusatives. In contrast to unergatives,<br />

in the basic word order, an unaccusative subject follows an unaccusative verb, as in<br />

(19). If the verb is new and the subject is given, the word order is reversed, as in (20).<br />

12 <strong>The</strong> proposal predicts that if there were rightward movement, a given element might follow a new element.<br />

Unfortunately, I am not aware <strong>of</strong> any case <strong>of</strong> rightward movement in Czech that would allow to test<br />

this prediction.<br />

13 I simplify the derivation here. In the full derivation, V moves to v, resulting into structure that requires<br />

another instance <strong>of</strong> G-movement. I will go through derivations in more details in the coming chapters. For<br />

now, I leave many details aside.<br />

15

(19) a. What happened?<br />

b. Přijel vlak.<br />

arrived train<br />

‘A train arrived.’<br />

(20) a. What happened to the train?<br />

b. Vlak || přijel.<br />

train arrived<br />

‘<strong>The</strong> train arrived.’<br />

This is basically the story. 14 <strong>The</strong>re are still many questions that need to be addressed –<br />

and I will address them in the coming sections and chapters – but the core <strong>of</strong> the argument<br />

is as simple as this: If a given element α G is asymmetrically c-commanded by a non-G<br />

element, α G needs to move. If there is no <strong>of</strong>fending c-command relation, G-movement<br />

does not take place.<br />

Before I approach developing the syntactic system in more detail, I want to shortly address<br />

what I mean by given.<br />

In the literature on information structure it is agreed, at least since Halliday (1967), that<br />

an utterance may be divided into two parts, one <strong>of</strong> which is more established in the discourse<br />

(common ground, context. . . ) than the other. While the terminology and the actual<br />

approaches vary widely (see for example Kruijff-Korbayová and Steedman (2003) for a<br />

recent overview), there is a strong intuition that the two parts are complementary to each<br />

other. Thus, it is a reasonable assumption that a grammar might refer only to one <strong>of</strong> the<br />

parts. <strong>The</strong> question then is which part is relevant.<br />

<strong>The</strong> approach I take here is based on the idea that the part encoded in the grammar is<br />

the given part (on given/new or given/focus scale). For arguments for this type <strong>of</strong> approach<br />

see, for instance, Williams (1997); Schwarzschild (1999); Krifka (2001); Sauerland (2005);<br />

Reinhart (2006).<br />

As to the question <strong>of</strong> how exactly given is defined for now I will adopt Schwarzschild’s<br />

definition <strong>of</strong> givenness, stated in (21). <strong>The</strong> definition is based on the observation that<br />

for element α to be given, which in English roughly corresponds to being deaccented, α<br />

must be entailed by the previous discourse and α must have a salient antecedent. Since<br />

entailment refers to proposition, the definition ensures that entailment can be stated for any<br />

α (not only propositional but also referential and predicational), (21-b).<br />

(21) Definition <strong>of</strong> Given (modified from Schwarzschild 1999, p. 151, (25))<br />

α is interpreted as Given in an utterance U iff there is a salient antecedent A such<br />

that<br />

a. α and A corefer; or<br />

14 <strong>The</strong>re is one crucial piece missing: dependence <strong>of</strong> G-movement on head movement. I will discuss this<br />

property in section 1.3 and 2.3.<br />

16

. A entails (α,U) where (α,U) is an utterance derived by replacing all maximal<br />

constituents <strong>of</strong> U (except for α) by variables existentially quantified over.<br />

Any other element is a non-G element.<br />

<strong>The</strong> definition will be more than sufficient for the discussion <strong>of</strong> the syntax <strong>of</strong> givenness in<br />

chapters 1–3. We will see, however, in chapter 4 that the proposed syntactic mechanism<br />

covers only a subset <strong>of</strong> the relevant cases. For the rest <strong>of</strong> the Czech empirical pattern we<br />

will need to combine the syntactic system with a semantic one. In chapter 4 we will also<br />

see that the Schwarzschild definition is too weak for the Czech facts. But all this must wait.<br />

Let’s concentrate on the syntax first.<br />

1.2 Basic word order and Focus projection<br />

This section shows that only basic word orders are compatible with multiple interpretations.<br />

In order to account for this fact, I will argue that the lack <strong>of</strong> ambiguity for derived orders<br />

follows from G-movement being a last resort operation. If a structure is such that there<br />

is no new (non-G) element asymmetrically c-commanding given α G , no G-movement is<br />

expected. <strong>The</strong> core idea that I will introduce in this section is that while a structure without<br />

any instance <strong>of</strong> G-movement may be compatible with several interpretations, G-movement<br />

always disambiguates.<br />

So far I have not established how we define the basic word order. I propose, following<br />

Veselovská (1995); Junghanns and Zybatow (1997); Lavine and Freidin (2002); Bailyn<br />

(2003), among others, that the basic word order in Czech is the all-new word order. This<br />

means that the basic word order is an order that can be used as a felicitous answer to the<br />

question What happened?. 15 An example <strong>of</strong> such an order is given in (22). Notice also that<br />

binding, which is sometimes used for determining basic word order, cannot be used as a<br />

diagnostic for Czech. <strong>The</strong> reason is that Slavic languages have A-movement scrambling<br />

that can change the basic word order and create new binding configurations. I will comment<br />

on binding properties <strong>of</strong> G-movement in appendix A.<br />

(22) Basic word order:<br />

A: What happened at the party?<br />

B 1 : [Marie dala Pavlovi facku] New .<br />

Marie.Nom gave Pavel.Dat slap.Acc<br />

B 2 : #Marie dala facku Pavlovi.<br />

Marie.Nom gave slap.Acc Pavel.Dat<br />

B 3 : #Pavlovi dala Marie facku.<br />

Pavel.Dat gave Marie.Nom slap.Acc<br />

B 4 : #Facku dala Marie Pavlovi.<br />

slap.Acc gave Marie.Nom Pavel.Dat<br />

‘Marie slapped Pavel. [literary: Marie gave Pavel a slap.]’<br />

15 <strong>The</strong> cited authors address only Slavic languages, more precisely Czech, Ukrainian, and Russian.<br />

17

It has also been observed that in basic word order various constituents may be understood<br />

as new. <strong>The</strong> only condition for an SVO language like Czech is that a new constituent be<br />

aligned to the right edge <strong>of</strong> a clause. We can test this property by using wh-questions<br />

targeting different constituents, as seen in (23).<br />

18

(23) What can be understood as new?<br />

a. (i) What did Marie give to Pavel?<br />

(ii) Marie dala Pavlovi [facku] New ←− slap<br />

b. (i) What did Marie give to whom?<br />

(ii) Marie dala [Pavlovi facku] New ←− Pavel a slap<br />

c. (i) What did Marie do?<br />

(ii) Marie [dala Pavlovi facku] New ←− gave Pavel a slap<br />

d. (i) What happened?<br />

(ii) [Marie dala Pavlovi facku] New ←− Marie gave Pavel a slap<br />

In contrast, if an utterance contains any deviance from the basic order, then such an utterance<br />

is infelicitous in an all-new context. It means that if any reordering takes place,<br />

at least one constituent must be α G , i.e., introduced in the previous discourse. In other<br />

words, any reordering limits the number <strong>of</strong> structural positions in which we can identify<br />

the partition between given and new. For example, in a derived word order, as in (24), there<br />

is only one felicitous interpretation <strong>of</strong> the information structure. More precisely, only the<br />

rightmost constituent can be interpreted as new (non-G). In this particular case, it is the<br />

indirect object Pavel. Thus, in (24) there is only one possible partition between given and<br />

new, in contrast to (22) that is compatible with several partitions, as schematized in (25).<br />

(24) Focus Projection within a derived word order:<br />

a. Marie dala facku [Pavlovi] New ←− S V DO || IO t DO<br />

b. #Marie dala [facku Pavlovi] New<br />

c. #Marie [dala facku Pavlovi] New<br />

d. #[Marie dala facku Pavlovi] New<br />

(25) a. Marie dala facku || Pavlovi.<br />

b. (||) Marie (||) dala (||) Pavlovi (||) facku.<br />

What we can learn from the observed pattern is that in basic word order there is a relative<br />

freedom in what parts <strong>of</strong> the utterance can be interpreted as new and what parts can be interpreted<br />

as given. As I have already anticipated in the previous discussion <strong>of</strong> G-movement,<br />

this pattern can be described in the following manner: whatever is interpreted as given cannot<br />

be linearly preceded by anything interpreted as new.<br />

Let’s now turn to the question <strong>of</strong> how exactly the multiple partition effect follows from<br />

our system. To see that, we will look at a very simple case: a transitive clause that has no<br />

modifiers, only a subject, a verb, and an object. Consider first the case where the subject is<br />

the only given element. As we already know, the resulting word order is SVO, as seen in<br />

(26) and (27). 16<br />

(26) a. Subject-G verb Object ←−<br />

b. #Object verb Subject-G<br />

16 I use here examples with potom ‘then, afterward’ instead <strong>of</strong> a wh-question. <strong>The</strong> reason is that potom<br />

creates a natural context where only the subject is presupposed/given. For reasons that are not clear to me, it<br />

is difficult to obtain the same pragmatic effect with a wh-question.<br />

19

c. #Subject-G Object verb<br />

d. . . .<br />

(27) What did Mary do afterward?<br />

a. (Potom) Maruška || zavolala nějakého chlapce ze sousedství.<br />

afterward Mary.Nom called some boy.Acc from neighborhood<br />

b. #(Potom) Maruška nějakého chlapce ze sousedství zavolala<br />

afterward Mary.Nom some boy.Acc from neighborhood called<br />

‘Afterward Mary called some boy from her neighborhood.’<br />

I have proposed in 1.1 that G-movement is a last resort operation. We predict that G-<br />

movement takes place only if there is a non-G element asymmetrically c-commanding the<br />

given subject. Since there is no such element, in this particular case there is no G-movement<br />

taking place. A corresponding tree representation is given in (28).<br />

20

(28) Derivation <strong>of</strong> [Subject]-G verb Object<br />

vP<br />

Subject G<br />

vP<br />

v<br />

VP<br />

t V<br />

Object<br />

Let’s now consider the same sentence but with both the subject and the verb given. An<br />

example is given in (29) and (30).<br />

(29) a. Subject-G verb-G Object ←−<br />

b. #Object verb-G Subject-G<br />

c. #Subject-G Object-G verb<br />

d. . . .<br />

(30) Whom did Mary call afterward?<br />

a. Potom Maruška zavolala || nějakého chlapce ze sousedství.<br />

then Mary.Nom called some boy.Acc from neighborhoud<br />

b. #Potom Maruška nějakého chlapce ze sousedství zavolala<br />

then Mary.Nom some boy.Acc from neighborhoud called<br />

‘<strong>The</strong>n Mary called some boy from her neighborhoud.’<br />

Since neither the subject nor the verb is asymmetrically c-commanded by anything new, it<br />

follows that the derivation should be the same as in (28). <strong>The</strong> reason is that in neither (26)<br />

nor (29) does G-movement take place. <strong>The</strong> representation I argue for is given in (31).<br />

21

(31) Derivation <strong>of</strong> [Subject]-G verb-G Object<br />

vP<br />

Subject G<br />

vP<br />

v-G<br />

VP<br />

t V<br />

Object<br />

<strong>The</strong> logic that arises is the following: if a structure is monotonous in the sense that there is<br />

no point where a new element would asymmetrically c-command a given element, syntax<br />

does not have any tool to mark what part exactly is given and what part exactly is new. In<br />

contrast, if there is any deviance from the basic word order, the partition between given<br />

and new is syntactically realized. Thus, the interpretation <strong>of</strong> the utterance is restricted by<br />

syntactic tools. I will argue in chapter 4 that if there is no G-movement, the partition is<br />

established by the semantic component.<br />

I argue that any basic word order sentence – if presented out <strong>of</strong> the blue – is ambiguous<br />

with respect to its information structure. Since there is no syntactic marking <strong>of</strong> the partition<br />

between given and new within basic word order determining the partition is left entirely to<br />

the semantic interface. I argue that this follows from the fact that in a neutral word order<br />

sentence there is no G-movement taking place. Thus the syntactic output <strong>of</strong> such a sentence<br />

is identical no matter how many semantic interpretations <strong>of</strong> the sentence are available.<br />

This conclusion is supported by the fact that there is no difference in prosody between<br />

(27-a) and (30-a). If we assume that phonology reads prosody directly <strong>of</strong>f the syntactic<br />

structure (see, for example, Bresnan 1972; Truckenbrodt 1995; Wagner 2005; Büring 2006,<br />

among many others) this is an unsurprising result. <strong>The</strong>refore, it is only the semantic component<br />

that may interpret such a clause in different ways depending on the actual context.<br />

For syntax and the syntax-phonology interface there is only one structure to be considered.<br />

Crucially, this behavior is a consequence <strong>of</strong> G-movement being a last resort operation. If G-<br />

movement had to take place whenever there was something potentially given, the semantic<br />

(but also word order and prosodic) ambiguity <strong>of</strong> the basic word order would be unexpected.<br />

In this section, we have seen that there is a close connection between the last resort<br />

character <strong>of</strong> G-movement and the multiple interpretations available for basic word orders.<br />

In the next section we will look at ambiguities that arise within derived orders. I will argue<br />

that this type <strong>of</strong> ambiguity follows from G-movement being dependent on head movement.<br />

1.3 Verb partitions and their semantic ambiguity<br />

In Czech the partition between given and new is <strong>of</strong>ten manifested by a finite verb. <strong>The</strong><br />

fact that Czech verbs usually appear between the given and the new part has already been<br />

observed by Vilém Mathesius (Mathesius, [1929] 1983, 1939). In the following Czech<br />

22

functionalist tradition there has been prevailing disagreement on whether the inflected verbal<br />

form can be characterized as given or new (for example, Sgall (1967); Hajičová (1974);<br />

Sgall et al. (1980)) or whether the verb forms a special category which is neither given nor<br />

new (for example, Firbas 1964; Svoboda 1984). I will argue that the finite verb is indeed either<br />

given or new. <strong>The</strong> reason why it is so difficult to characterize its information structure<br />

status is that the verb is <strong>of</strong>ten ambiguous between being given and new. More precisely,<br />

the partition between given and new <strong>of</strong>ten either immediately precedes the finite verb or<br />

immediately follows it.<br />

I will argue that this is a side-product <strong>of</strong> an independent property <strong>of</strong> G-movement. In<br />

particular, I will argue that G-movement is parasitic on head movement. <strong>The</strong> idea that<br />

a certain type <strong>of</strong> movement may be dependent on head movement has been already proposed<br />

in other contexts (see, for example, Holmberg 1986 for Object shift and Heycock<br />

and Kroch 1993; Johnson 2002 for coordination) but it is not well understood. I will provide<br />

a possible motivation <strong>of</strong> this restriction on G-movement in section 2.3. In this section<br />

I will show that we can find two possible motivations for head movement in connection<br />

with G-movement. Either (i) head movement is an independent instance <strong>of</strong> G-movement,<br />

and the verb is given, or (ii) the verb is new and head movement facilitates G-movement<br />

<strong>of</strong> some other element. In both cases head movement is understood as part <strong>of</strong> the narrow<br />

syntax (contrary to Chomsky (2000, 2001, 2004a)).<br />

In the simple cases we have considered so far, the relative word order <strong>of</strong> the new part<br />

was the same as the basic word order. Consider (32).<br />

(32) a. And what about the lollipop?<br />

b. #Lízátko malá holčička našla.←− # O || S V<br />

lollipop.Acc little girl.Nom found<br />

c. Lízátko || našla malá holčička. ←− O || V S<br />

lollipop.Acc found little girl.Nom<br />

‘A little girl found the lollipop.’<br />

Our system as it is set up now predicts that the word order <strong>of</strong> the new elements should not<br />

change, thus, the verb should linearly follow the subject, as in (32-b). This prediction is,<br />

however, incorrect. As we see in (32-c), the verb must precede the subject. I argue that this<br />

is a result <strong>of</strong> a more general restriction on G-movement that has not been discussed yet. A<br />

first approximation <strong>of</strong> the restriction is given in (33). I will discuss the restriction in further<br />

detail in section 2.3.<br />

(33) Head movement restriction on G-movement:<br />

α G can G-move out <strong>of</strong> XP only if X 0 moves out <strong>of</strong> XP as well.<br />

<strong>The</strong> restriction is meant to capture the fact that if α G G-moves, the head in which projection<br />

α G was base generated moves as well. We will see only in section 2.3 how exactly<br />

the head movement restriction is motivated and when it applies. For now, let’s stay with<br />

the following claim: there are two cases in which a head moves because <strong>of</strong> G-movement:<br />

(i) the head itself is given and as such it needs to undergo G-movement; (ii) the head itself<br />

23

is not given but its movement is necessary to facilitate G-movement <strong>of</strong> some other given<br />

element.<br />

As a consequence, we predict that the verb may appear on either side <strong>of</strong> the partition<br />

between given and new. 17 If the head itself undergoes G-movement, the partition follows<br />

the head. 18 If the head moves in order to facilitate G-movement, the partition precedes the<br />

head. Thus we predict the pattern to be as in (34).<br />

(34) a. O V || S ←− head undergoes G-movement<br />

b. O || V S ←− head facilitates G-movement<br />

<strong>The</strong> pattern is indeed correct. Example (32-c) is not only a felicitous answer to the question<br />

And what about the lollipop? What happened to the lollipop? but it is also a felicitous<br />

answer to the question Who found the lollipop?, as in (35).<br />

(35) a. Who found the lollipop?<br />

b. Lízátko našla || malá holčička.<br />

lollipop.Acc found little girl.Nom<br />

‘A little girl found the lollipop.’<br />

In other words, the semantic ambiguity that we found with a basic word order repeats itself<br />

on a smaller scale here as well. Even though we know that because <strong>of</strong> G-movement <strong>of</strong><br />

the object, the object is given (translated as the lollipop), we cannot conclude anything<br />

about the status <strong>of</strong> the verb. <strong>The</strong> reason is that the head might have undergone either G-<br />

movement, or it might have moved only in order to facilitate G-movement. <strong>The</strong> suggested<br />

derivation is given in (36). For now I leave open the question <strong>of</strong> the exact landing site <strong>of</strong><br />

G-movement. In the following graphs, the landing site is marked as ?P.<br />

(36) a. VP<br />

V<br />

Object<br />

b. vP<br />

Subject<br />

vP<br />

v-V<br />

VP<br />

V<br />

Object<br />

17 Notice that the verb can be either the rightmost element in the given part, or it can follow the given part<br />

but it can never intervene between two given elements. Thus if, for example, both the subject and the object<br />

are given the resulting order is either SOV or OSV, depending on other factors such as topicalization.<br />

18 I put aside for now what determines the relative order <strong>of</strong> the given elements. I will address this question<br />

in chapter 3.<br />

24

c. ?P<br />

v-V<br />

vP<br />

Subject<br />

vP<br />

v-V<br />

VP<br />

V<br />

Object<br />

d. ?P<br />

Object ?P<br />

v-V<br />

vP<br />

Subject<br />

vP<br />

v-V<br />

VP<br />

V<br />

Object<br />

I argue that the only difference between the interpretation in which the verb is given and the<br />

interpretation in which the verb is new is in the motivation for head movement. Thus, the<br />

syntactic output for PF and LF is the same. For native speakers, OVS structures presented<br />

out <strong>of</strong> the blue are ambiguous and there is also no difference in the prosody they could use<br />

to disambiguate.<br />

We have now seen that there are two configurations under which information structure<br />

ambiguity arises: either no G-movement takes place, thus, no partition is established, or the<br />

partition could be placed in more than one position because there is no way to distinguish<br />

between G-movement <strong>of</strong> the verb and independently motivated verb movement. It is left<br />

up to the semantic interface to decide according to the relevant context. In chapter 4 I will<br />

present a semantic system which is designed to make this type <strong>of</strong> decision.<br />

In order to obtain the ambiguity <strong>of</strong> the new versus given partition with respect to the<br />

verb and in order to derive the correct word order, I have assumed that G-movement is<br />

dependent on head movement. In the next section I will look closely at predictions this assumption<br />

makes. I will present evidence that the domain in which G-movement takes place<br />

is indeed independently restricted by restrictions on head movement. Thus, head movement<br />

and G-movement share the same locality restrictions. This fact thus provides further<br />

25

support in favor <strong>of</strong> the assumption that G-movement is dependent on head movement.<br />

1.4 <strong>The</strong> boundedness <strong>of</strong> G-movement<br />

In this section, I will explore the further predictions and consequences <strong>of</strong> restricting G-<br />

movement by head movement, namely, differences in locality restrictions on G-movement<br />

that depend on the movement properties <strong>of</strong> the relevant facilitating head.<br />

First <strong>of</strong> all, since head movement is clause bounded, we expect G-movement to be<br />

clause bounded as well. This is indeed correct. As we can see in the following examples,<br />

given elements can move only to the edge <strong>of</strong> their own embedded clause, even if the matrix<br />

clause introduces only new information.<br />

(37) For a long time I didn’t know what was going on with Mary.<br />

a. Ale pak mi bývalá spolužačka řekla, že Marie si vzala Petra.<br />

but then me former classmate told that Marie.Nom REFL took Petr.Acc<br />

‘But then a former classmate <strong>of</strong> mine told me that Marie got married to Petr.’<br />

b. Ale pak mi bývalá spolužačka řekla, že Marii potkalo velké<br />

but then me former classmate told that Marie.Acc met big<br />

štěstí.<br />

happiness<br />

‘But then a former classmate <strong>of</strong> mine told me that Marie got extremely lucky.<br />

(She won a lottery.)’<br />

c. #Marii mi bývalá spolužačka řekla, že potkalo velké štěstí.<br />

Marie.Acc me former classmate told that met big happiness<br />

In this respect G-movement differs from both wh-movement and contrastive focus movement,<br />

which are not clause bound, as can be seen in (38) and (39).<br />

(38) Koho, že jsi říkala, že si Marie<br />

whom.Acc that Aux-you said that REFL Marie.Nom<br />

‘Whom did you say Marie is going to Mary?’<br />

bude<br />

will<br />

brát?<br />

take<br />

(39) Pavla, jsem ti říkala, si bude brát Marie, ne Lucie.<br />

Pavel.Acc Aux-I you.Dat said REFL will take Marie.Nom not Lucie.Nom<br />

‘I’ve (already) told you that it is Pavel who is going to marry Marie not Lucie.’<br />

If G-movement were only restricted to clause boundaries, one might come up with another<br />

explanation. For example, one could argue that this follows from the fact that G-movement<br />

is A-movement (see appendix A for details)sec:AMovement. If this were the right explanation,<br />

we would not expect further locality restrictions. In contrast, if G-movement is<br />

restricted by head movement, we predict that G-movement is also not possible out <strong>of</strong> infinitival<br />

domains because the infinitive head cannot move out <strong>of</strong> the domain either. <strong>The</strong><br />

latter prediction is borne out, as can be seen in (40). <strong>The</strong> relevant verbal head is marked by<br />

a box.<br />

26

(40) What happened to the antique chair you got many years ago from Mary?<br />

a. Můj bývalý partner se pokusil tu židli<br />

my former partner REFL tried that chair<br />

‘My ex-partner tried to burn the chair.’<br />

b. Můj bývalý partner chtěl tu židli spálit .<br />

my former partner wanted that chair burn.Inf<br />

‘My ex-partner wanted to burn the chair.’<br />

c. Můj bývalý partner dokázal tu židli spálit .<br />

my former partner managed that chair burn.Inf<br />

‘My ex-partner managed to burn the chair.’<br />

d. #Tu židli můj bývalý partner dokázal spálit .<br />

that chair my former partner managed burn.Inf<br />

spálit .<br />

burn.Inf<br />

‘My ex-partner managed to burn the chair. (OK: As to the chair, my expartner<br />

managed to burn it.)’<br />

If we do not bind G-movement to head movement, this behavior is unexpected also because<br />

other elements, for example clitics, can climb up from the infinitival domain as in (41) with<br />

a reflexive tantum posadit se ‘sit down’.<br />

(41) a. Petr se chtěl posadit .<br />

Petr.Nom REFL wanted sit-down<br />

‘Petr wanted to sit down.’<br />

b. Petr se dokázal posadit<br />

Petr.Nom REFL managed sit-down<br />

‘Petr managed to sit down.’<br />

.<br />

If we assume that infinitives that allow clitic climbing are restructuring verbs (cf. Dotlačil<br />

2004; Rezac 2005), then the infinitival restriction on G-movement cannot follow from presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> a phase boundary. Whatever allows the clitic to get to the main clause, should be<br />

able to get the given element out as well. 19 As we can see, however, this is not so. On the<br />

other hand, if we allow G-movement <strong>of</strong> α G to take place only if the relevant head moves as<br />

well, the difference between clitics and given material is predicted.<br />

Furthermore, we predict that if a verbal head is selected by another verbal head (an<br />

auxiliary), G-movement should be blocked as well. We find a useful minimal pair if we<br />

compare sentences in the Present or the Past tense with sentences in the Future tense. <strong>The</strong><br />

main verb in the future tense, in contrast to other tenses where the verb moves out <strong>of</strong> VP,<br />

stays in VP and the future auxiliary is base generated in vP (Veselovská, 2004; Kučerová,<br />

2005). As we can see in (42), (43), and (44), the difference in the different head movement<br />

properties, especially lack <strong>of</strong> head movement in the Future tense, propagates to the domain<br />

in which an element can undergo G-movement. While in (42) and (43) the verbal head is<br />

free to move and the given object can therefore G-move, in (44) the given object can only<br />

19 Clitic climbing in Czech is a syntactic, not a phonological, process. This can be shown, for example, by<br />

the fact that different clitics in Czech climb differently. See Dotlačil 2004 for more details.<br />

27

immediately precede the main verb. Any other instance <strong>of</strong> G-movement is not possible. 20<br />

(42) a. What happened to the book?<br />

b. Tu knihu || dala Marie Petrovi. ←− Past<br />

the book.Acc gave Marie.Nom Petr.Dat<br />

‘Marie gave the book to Petr.’<br />

(43) a. What is happening to the book?<br />

b. Tu knihu || dává Marie Petrovi. ←− Present<br />

the book.Acc gives Marie.Nom Petr.Dat<br />

‘Marie gives the book to Petr.’<br />

(44) a. What will happen to the book?<br />

b. Marie bude tu knihu dávat<br />

Marie.Nom will the book.Acc give.Inf<br />

‘Marie will give the book to Peter.’<br />

c. #Tu knihu bude Marie dávat<br />

the book.Acc will Marie.Nom give.Inf<br />

Petrovi. ←− Future<br />

Petr.Dat<br />

Petrovi.<br />

Petr.Dat<br />

‘Marie will give the book to Peter.’<br />

(OK as ‘As to the book (in contrast to the violin), Marie will give it to Peter.)<br />

Interestingly, we find differing morphology even within one tense – the past tense. While<br />

there is no overt auxiliary for 3rd person, 1st and 2nd person are formed by a finite auxiliary<br />

and a past participle. If G-movement depends on head movement we predict non-local G-<br />

movement <strong>of</strong> a given object to be possible with a 3rd person subject but not with a 1st or a<br />

2nd person subject. This prediction is indeed correct, as can be seen in (66) and (67).<br />

(45) 3sg.: Non-local G-movement possible:<br />

a. What happened to the boat that got demeged in the last storm?<br />

b. Lod’ opravil jeden technik.<br />

boat.Acc repaired one technician.Nom<br />

‘A technician repaired the boat.’<br />

(46) 1pl.: Only local G-movement:<br />

a. What happened to the boat that got demaged in the last storm?<br />

b. Jeden technik a já jsme lod’ opravili .<br />

one technician.Nom and I Aux.1pl boat.Acc repaired<br />

‘A technician and I repaired the boat.’<br />

Tying G-movement to head movement makes an additional prediction. If there is no head<br />

that can move, only very local G-movement should be possible. A case to consider is a<br />

small clause. As we can see in (47), this prediction is indeed correct. As with infinitives,<br />

in a small clause, a given element can undergo only very local G-movement. No further<br />

20 <strong>The</strong>se examples are vastly simplified. To keep the pairs minimal I use an iterative form in the present<br />

tense. <strong>The</strong> reason is that the corresponding word does not have a periphrastic future. Another important point<br />

is that (44-c) is a plausible structure but the object would have to be interpreted as a topic (As to the book,<br />

Marie will give the book to Peter.).<br />

28

movement is possible.<br />

(47) a. Why does Peter look so happy?<br />

b. Marie je na Petra pyšná<br />

Marie.Nom is <strong>of</strong> Petr proud<br />

‘Marie is found <strong>of</strong> Peter.’<br />

c. #Na Petra je Marie pyšná.<br />

<strong>of</strong> Petr is Marie proud<br />

.<br />

Another interesting pattern arises from interactions <strong>of</strong> G-movement and the EPP requirement<br />

<strong>of</strong> T. Simplifying considerably, in Czech T attracts whatever is the structurally closest<br />

element (for more details see Kučerová (2005)). Thus, if there is a subject in Spec,vP, T<br />

attracts the subject. On the other hand, if there is no subject (Czech is a pro-drop language),<br />

T may attract the verbal head occupying v. See the examples in (48) and (49), illustrating<br />

the point.<br />

(48) a. Marie koupila husu.<br />

Marie.Nom bought goose.Acc<br />

‘Marie bought a goose.’<br />

b. [ TP Marie T [ vP t Marie bought goose ] ]<br />

(49) a. Koupila husu.<br />

bought goose.Acc<br />

‘She bought a goose.’<br />

b. [ TP bought T [ vP t bought goose ] ]<br />

We can now make an interesting prediction. If a given element moves to the left edge <strong>of</strong><br />

vP, then it can be attracted by T even if T is realized as an auxiliary. Thus, we expect to<br />

find a word order that superficially looks like a violation <strong>of</strong> the head movement constraint<br />

on G-movement. This is correct, as can be seen in (51). Notice that there is nothing wrong<br />

with moving a given element over an auxiliary. <strong>The</strong> given element just cannot undergo<br />

G-movement. Other instances <strong>of</strong> movement are not a problem.<br />

(50) Scenario: And what about all the money you inherited?<br />

(51) Všechny peníze jsem poslala osamělým dětem. ←− Past<br />

all money Aux.1sg sent lonely children.Dat<br />

‘I sent all (the) money to lonely children.’<br />

(52) Past tense:<br />

a. VP level: the given object moves over V:<br />

29

VP<br />

money<br />

VP<br />

gave<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

b. V moves to v:<br />

vP<br />

gave<br />

VP<br />

money<br />

VP<br />

t gave<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

c. the object undergoes G-movement over v:<br />

vP<br />

money<br />

vP<br />

gave<br />

VP<br />

t money<br />

VP<br />

t gave<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

d. T-auxiliary is merged and probes for the closest element:<br />

30

TP<br />

Aux<br />

vP<br />

money<br />

vP<br />

gave<br />

VP<br />

t money<br />

VP<br />

t gave<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

e. the given object moves to T:<br />

TP<br />

money<br />

TP<br />

Aux<br />

vP<br />

t money<br />

vP<br />

gave<br />

VP<br />

t money<br />

VP<br />

t gave<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

In contrast, in the future tense there is no V-to-v movement. Thus, a given object cannot<br />

reach the vP edge, as shown by the object in (54). Since the future auxiliary is base generated<br />

in v and there is no overt subject, T attracts the auxiliary. <strong>The</strong> derivation is schematized<br />

in (55).<br />

(53) Scenario: And what about all the money you will inherit?<br />

(54) Budu všechny peníze posílat osamělým dětem.←− Future<br />

will.1sg all money send.Inf lonely children.Dat<br />

31

‘I will send all (the) money to lonely children.’<br />

(55) Future tense:<br />

a. VP level: the given object moves over V:<br />

VP<br />

money<br />

VP<br />

give<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

b. v-auxiliary is merged and the object cannot G-move further:<br />

vP<br />

Aux<br />

VP<br />

money<br />

VP<br />

give<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

c. T is merged and probes for the closest element:<br />

TP<br />

T<br />

vP<br />

Aux<br />

VP<br />

money<br />

VP<br />

give<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

d. the auxiliary moves to T:<br />

32

TP<br />

Aux<br />

TP<br />

T<br />

vP<br />

t Aux<br />

VP<br />

money<br />

VP<br />

give<br />

VP<br />

children<br />

t money<br />

Notice that the sentences we have considered in this section crucially differ from the sentences<br />

that originally motivated introducing G-movement into the system. <strong>The</strong> difference<br />

is that if head movement is blocked, α G may be asymmetrically c-commanded by new<br />

material. Recall the definition <strong>of</strong> G-movement from (11), repeated below as (56). Even<br />

though we can identify what element must be given, we cannot establish a perfect partition<br />

between given and new as we were able to do in the previous cases.<br />

(56) G-Movement [version 1]<br />

G-movement must take place<br />

a. iff α G is asymmetrically c-commanded by a non-G element,<br />

b. unless the movement is independently blocked.<br />

<strong>The</strong> definition <strong>of</strong> G-movement given in (11)/(56) takes care <strong>of</strong> these cases with the clause<br />

unless the movement is independently blocked. Thus, the pattern that arises can be described<br />

as do as much as you can. But does this mean that anything goes? I will address<br />

this question in the next section. I will show that if α G is required to G-move, α G must<br />

move at least once.<br />

In chapter 4, I will address the question why it is sometimes okay to move a given element<br />

only locally even if there is a higher new element, while in other cases, non-local<br />