IOM - Assessment on the Psychosocial Needs of Haitians Affected ...

IOM - Assessment on the Psychosocial Needs of Haitians Affected ...

IOM - Assessment on the Psychosocial Needs of Haitians Affected ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Assessment</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Psychosocial</strong> <strong>Needs</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Haitians</strong><br />

<strong>Affected</strong> by <strong>the</strong> January 2010 Earthquake<br />

Acti<strong>on</strong> C<strong>on</strong>tre la Faim (ACF), Adventist Development and Relief Agency-Haiti (ADRA), Centre d’Educati<strong>on</strong> Populaire et<br />

Enfants du m<strong>on</strong>de et droits de l’Hommev (CEP), Centre Marie Denise Claude, Fédérati<strong>on</strong> Luthérienne M<strong>on</strong>diale, French Red<br />

Cross (FRC), Handicap Internati<strong>on</strong>al (HI), Hosean Internati<strong>on</strong>al Ministry (HIM), Médecins du M<strong>on</strong>de Canada (MDM-<br />

Canada), Plan-Haiti, Save <strong>the</strong> Children, Société Jeunesse Acti<strong>on</strong> (SAJ), World Visi<strong>on</strong> (WV)

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Assessment</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Psychosocial</strong> <strong>Needs</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Haitians</strong><br />

<strong>Affected</strong> by <strong>the</strong> January 2010 Earthquake<br />

Port Au Prince, Haïti, September 2010<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Organizati<strong>on</strong> for Migrati<strong>on</strong> (<str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>)<br />

Editorial Team<br />

Editors: Amal Ataya, Patrick Duigan, Dorothy Louis, Guglielmo Schinina’<br />

Research Team<br />

Research C<strong>on</strong>cepti<strong>on</strong>: Guglielmo Schinina’<br />

Computati<strong>on</strong>, Data Entry and Data analysis: Geordany Philistin, Mohammad Halabi<br />

Researchers: Mazen Aboul Hosn, Amal Ataya, Po<strong>on</strong>am Dhavan, Dieuvet Gaity, Dorothy<br />

Louis, Marie Adele Salem.<br />

Data Entry: Jean Bernard, Pierre Claud<strong>on</strong>ique, Joseph Marjorie, Augustin Nadège, François<br />

Randy, Josesph Snold.<br />

Interviewers: Acti<strong>on</strong> C<strong>on</strong>tre la Faim :Alcine Emmanuela, Duclervil Faniole, Fanel Dumay,<br />

Jean Baptiste Yamiley, Jean Baptiste Yves Marly,John Carl Peters<strong>on</strong>, Joseph Jean Germy,<br />

Lamarre Phenia, Louis Wilsot, Pierre Nerlande, Rémy Yrmine, Robert Fabiola, Saint-Vil Alex,<br />

Sim<strong>on</strong> Jacks<strong>on</strong>, Sim<strong>on</strong> Samuel, Thadal Raym<strong>on</strong>de, Toussaint Cébien, Valcin Alfred, Vernet<br />

Elie, Zéphirin Johnny ; Adventist Development and Relief Agency-Haiti: Aurélien M. Judith,<br />

Guillaume A. Maria, Wildor Franck Junior; Centre d’Educati<strong>on</strong> Populaire (CEP) et Enfants<br />

du m<strong>on</strong>de et droits de l’Homme : Lominy Vanel ;Centre Marie Denise Claude: Claude<br />

Jorel, Claude Marie Denise, Comité de la Cour des Enfants de Quetsar: Desrosiers<br />

Christèle, Desrosiers Nathalie, Phanord Nédgie ;Fédérati<strong>on</strong> Luthérienne M<strong>on</strong>diale: Fergile<br />

Nyrka, Gédé<strong>on</strong> Edwige ; French Red Cross: Delva Guy ; Handicap Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

:Desgraviers Gabriel, Rizk Sarah ; Hosean Internati<strong>on</strong>al Ministry: Salnave Vista ; <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>: Aly<br />

Jacques Sully, Aris<strong>the</strong>ne Mario, Augustin Maxime, Brutus Liline, Camille Chantale, Caze Jean<br />

Id<strong>on</strong>al, Desmorne Suzanne, Desrisiers Jean Junior, Fer<strong>on</strong> Jean Mozart, Frédérique Jean<br />

D<strong>on</strong>elet, Gabriel Pierre Junior, Georges Carl Henry, Innocent Jean Valens, Jean Pierre Jean<br />

Sylvio, Jean Robert, Joseph Eline, Laguerre Nancy Verdieu, Leroy Youkens, Medee Ewen<br />

Sim<strong>on</strong>, Mirand Fenel, Nozil Rose Jeannette, Obas Le<strong>on</strong>, Ostiné Richenel, Pascal Gladimy, Paul<br />

Olivia, Pierre Louis Alwrich, Pierre Louis May France Larose, Pierre Paul Henry Robert,<br />

Rousseau Linda, Saget Paul Wilkins, Voltaire Justin Louis ; Médecins du M<strong>on</strong>de Canada:<br />

Di<strong>on</strong> Guylaine, Jean Philippe Fabiola, Joseph Anjelo, Plan-Haïti: Ladouceur Jean Charles,<br />

Menard Jean Wesly, Pierre Andrieu; Save <strong>the</strong> Children: Galland Frantz, Lector Sandra;<br />

Société Jeunesse Acti<strong>on</strong> : Francill<strong>on</strong> Willio, World Visi<strong>on</strong> Saintiné Miguel

Cover photo: Painting by IDP adolescents at Corail Camp and <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g> artistic animator<br />

Mario Aristene<br />

For more informati<strong>on</strong> regarding <strong>Psychosocial</strong> Activities in Haiti, c<strong>on</strong>tact <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g> Haiti<br />

Health Unit at iomhaitihu@iom.int<br />

For <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g> Global psychosocial programming, c<strong>on</strong>tact <strong>the</strong> Mental Health, <strong>Psychosocial</strong><br />

Resp<strong>on</strong>se and Intercultural Communicati<strong>on</strong> Secti<strong>on</strong> at mhddpt@iom.int<br />

Opini<strong>on</strong>s expressed in this publicati<strong>on</strong> are those <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> authors and do not necessarily<br />

reflect <strong>the</strong> views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Organizati<strong>on</strong> for Migrati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publicati<strong>on</strong> may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval<br />

system or transmitted in any form by any means electr<strong>on</strong>ic, mechanical, photocopying,<br />

recording, or o<strong>the</strong>rwise without prior written permissi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> publisher.<br />

3

Acknowledgements<br />

Gratitude goes to:<br />

All <strong>Haitians</strong> and those service providers who took part in <strong>the</strong> study as interviewers,<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>dents and in <strong>the</strong> committees for <strong>the</strong> revisi<strong>on</strong> and cultural c<strong>on</strong>sistency <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> tools.<br />

In particular to <strong>the</strong> staff <strong>of</strong> Acti<strong>on</strong> C<strong>on</strong>tre La Faim Croix-Rouge Française, Adventist<br />

Development and Relief Agency Haiti, Assembly <strong>of</strong> Jehovah Witness, Center Gaou<br />

Ginou-Kosanba, Center Marie Denise Claude, Center <strong>of</strong> Trauma, Centre D’Educati<strong>on</strong><br />

Populaire, Centre d’Educati<strong>on</strong> Populaire (CEP) et Enfants du m<strong>on</strong>de et droits de<br />

l’Homme, Centre Marie Denise Claude, Centre Psychiatrique Mars and Klien, Coaliti<strong>on</strong><br />

de la Jeunesse Haitienne pour l’integrati<strong>on</strong> (COJHIT), Comite de Gesti<strong>on</strong> (Camp<br />

tapis/Athletique II), Comite Victime Séisme, Directi<strong>on</strong> de la Protecti<strong>on</strong> Civile, Faculty <strong>of</strong><br />

Ethnology-State University <strong>of</strong> Haiti, Faculty <strong>of</strong> Human Sciences- State University <strong>of</strong><br />

Haiti, Federati<strong>on</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>rienne M<strong>on</strong>diale, Food for Hungry, Gheskio Center, Group<br />

Interventi<strong>on</strong> for Children (GIC), Group <strong>of</strong> Interventi<strong>on</strong> for Children, Haiti Tchaka<br />

dance(HTD), Handicap Internati<strong>on</strong>al, Plan Internati<strong>on</strong>al Haiti, Holistic Health Center,<br />

Hosean Internati<strong>on</strong>al Ministries, Internati<strong>on</strong>al Training and Educati<strong>on</strong> Center- I Tech, KF<br />

Foundati<strong>on</strong> (Kore Timoun), Medecin du M<strong>on</strong>de Canada, Ministry <strong>of</strong> Culture, Missi<strong>on</strong>ary<br />

<strong>of</strong> Sacre Cœur, Norwegian Church Aid, People in Need, Plas timun, Partners in Health,<br />

SAJ Associati<strong>on</strong>, Saúde em Português Haiti relief, Societe Acti<strong>on</strong> Jeunesse (SAJ) Comite<br />

de la Cour des Enfants de Quetsar (COCEQ), Uni<strong>on</strong> des Jeunes pour le Développent<br />

Humain Réel et Durable (UJDHRD),World Visi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

To Mark Van Ommeren (WHO) and Amanda Melville and Emanuel Streel (UNICEF) for<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir technical inputs and to all participants in Haiti MHPSS working group and MHPSS<br />

network, who gave <strong>the</strong>ir support.<br />

To <strong>the</strong> staff <strong>of</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g> Haiti, especially <strong>the</strong> CoM Luca Dall’Oglio and <strong>the</strong> former CoM<br />

Vincent Houver, <strong>the</strong> Camp Coordinati<strong>on</strong> and Camp Management Unit (CCCM), <strong>the</strong><br />

Health Unit, and <strong>the</strong> Mental Health, <strong>Psychosocial</strong> Resp<strong>on</strong>se and Intercultural<br />

Communicati<strong>on</strong> Secti<strong>on</strong> at Migrati<strong>on</strong> Health Divisi<strong>on</strong> at HQ-Geneva.<br />

4

Glossary <strong>of</strong> Terms<br />

AAD<br />

ACDI/VOCA<br />

ACF<br />

ACSI<br />

ACTED<br />

ADRA<br />

AIR<br />

ANOVA<br />

ARC<br />

AVSI<br />

CARE<br />

CISP<br />

COCEQ<br />

CRF<br />

CRS<br />

DDC<br />

Cooperati<strong>on</strong><br />

Suisse<br />

DINEPA<br />

DTM<br />

ENS<br />

FBO<br />

FHI<br />

FPGL<br />

FPN<br />

GJARE<br />

GoH<br />

GRET<br />

HI – Haiti<br />

IASC<br />

IDEJEN<br />

IDEO<br />

IDP<br />

IFRC<br />

IMC<br />

Adversity Activated Development<br />

(Internati<strong>on</strong>al Cooperative Development Associati<strong>on</strong>/<br />

Volunteer Development Corps)<br />

Acti<strong>on</strong> C<strong>on</strong>tre la Faim<br />

Associat<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Christian Schools Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Agence d’Aide à la Coopérati<strong>on</strong> Technique Et au<br />

Développement<br />

Adventist Development and Relief Agency<br />

American Institute <strong>of</strong> Research<br />

Analysis <strong>of</strong> Variance<br />

American Red Cross<br />

Associati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Volunteers in Internati<strong>on</strong>al Service<br />

Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere<br />

Comitato Internazi<strong>on</strong>ale per lo Sviluppo dei Popoli<br />

(The Internati<strong>on</strong>al Committee for <strong>the</strong> Development <strong>of</strong><br />

Peoples)<br />

Comite de la Cour des Enfants de Quetsar<br />

Croix Rouge Française (French Red Cross)<br />

Caritas/Catholic Relief Services<br />

La Directi<strong>on</strong> de Développement et de la Coopérati<strong>on</strong><br />

Directi<strong>on</strong> Nati<strong>on</strong>ale de l’Eau Portable et de<br />

l’Assainissement<br />

Displacement Tracking Matrix<br />

Ecole Normale Supérieure<br />

Faith Based Organizati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Family Health Internati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

F<strong>on</strong>dati<strong>on</strong> Paul Gérin-Lajoie<br />

Fod de Parrainage Nati<strong>on</strong>al<br />

Youth in Acti<strong>on</strong> for Reform<br />

Government <strong>of</strong> Haiti<br />

Groupe de Recherche et d’Exchanges Technologiques<br />

Handicap Internati<strong>on</strong>al – Haiti<br />

Interagency Standing Committee<br />

Initiative Pour Le Developpement des Jeunes<br />

Institut de Développement Pers<strong>on</strong>nel et Organisati<strong>on</strong>nel<br />

Internally Displaced Pers<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Federati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Red Cross<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Medical Corps<br />

5

<str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

IRC<br />

ITECH<br />

MHPSS<br />

MSF<br />

MSH<br />

NGO<br />

OCHA<br />

PAHO<br />

Prodev<br />

PTSD<br />

RAP<br />

SAJ<br />

SPSS<br />

UNCOR<br />

UNICEF<br />

URAMEL<br />

WHO<br />

WV<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Organizati<strong>on</strong> for Migrati<strong>on</strong><br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Rescue Committee<br />

Internati<strong>on</strong>al Training and Educati<strong>on</strong> Center for Health<br />

Mental Health and <strong>Psychosocial</strong> Support<br />

Médecins Sans Fr<strong>on</strong>tière<br />

Management Science <strong>of</strong> Health<br />

N<strong>on</strong>-governmental Organizati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

Organizati<strong>on</strong> for <strong>the</strong> Coordinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> Humanitarian<br />

Affairs<br />

Pan American Health Organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

Progress and Development<br />

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder<br />

Rapid Appraisal Procedures<br />

Société Jeunesse Acti<strong>on</strong><br />

Statistical Package for <strong>the</strong> Social Sciences<br />

United Methodist Committee <strong>on</strong> Relief<br />

United Nati<strong>on</strong>s Children’s Fund<br />

Unité de Recherche et d’Acti<strong>on</strong> Médico Légale<br />

World Health Organizati<strong>on</strong><br />

World Visi<strong>on</strong><br />

6

Table <strong>of</strong> C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

Executive Summary ......................................................................................................8<br />

I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................14<br />

II. METHODS........................................................................................................20<br />

III. RESULTS ..........................................................................................................25<br />

IV. DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ..........................................................40<br />

Annexes......................................................................................................................46<br />

Annex I: List <strong>of</strong> Interviewees for <strong>the</strong> psychosocial needs assessment Haiti .................................47<br />

Annex II: Questi<strong>on</strong>naire for internati<strong>on</strong>al and nati<strong>on</strong>al stakeholders..........................................49<br />

Annex III: The Names <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Study Participants’ Camps .......................................................................52<br />

Annex IV: Study Questi<strong>on</strong>naire ........................................................................................................................53<br />

References..................................................................................................................63<br />

7

Executive Summary<br />

The 12 January earthquake which struck <strong>the</strong> Haitian coast, followed by several o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

aftershocks, has greatly damaged various cities in Haiti. At <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> August 2010, <strong>the</strong><br />

government and humanitarian community estimated that over 2 milli<strong>on</strong> people had been<br />

affected, 222,570 individuals died, with an estimated 80,000 corpses still missing;<br />

188,383 houses were destroyed or partially damaged, and 1.5 milli<strong>on</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>s were still<br />

displaced in 1,368 settlement sites (OCHA-Humanitarian Bullettin, 30 th July 2010). Most<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se families are still living in tents or self-made shelters c<strong>on</strong>structed from tarpaulin<br />

and wood. Service delivery to <strong>the</strong>se sites remains limited with <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> efforts<br />

focused <strong>on</strong> addressing immediate needs in camps.<br />

9,000 individuals <strong>on</strong>ly, identified as being at high risk <strong>of</strong> dangerous flooding, have been<br />

relocated to <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly land identified by <strong>the</strong> government by <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> September 2010,<br />

while some land owners and schools have started evicting <strong>the</strong> displaced. Surveys have<br />

indicated that whilst some 40% <strong>of</strong> homes remain intact, many people are unwilling to<br />

return to <strong>the</strong>ir home or property due to both fear <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r earthquake, and <strong>the</strong> fear <strong>of</strong><br />

loosing <strong>the</strong> services currently provided in <strong>the</strong> camps (UNOPS- Safe Shelter Strategy, 14 Th<br />

April, 2010).<br />

Agencies working within <strong>the</strong> humanitarian cluster tasked with Shelter c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> have<br />

provided 6,868 transiti<strong>on</strong>al shelters to more than 34,000 individuals up to September<br />

2010 (OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, 30 July 2010). The Government <strong>of</strong> Haiti is<br />

encouraging IDPs to return to <strong>the</strong>ir homes, but <strong>the</strong>se efforts have so far yielded few<br />

results.<br />

The <str<strong>on</strong>g>Assessment</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Psychosocial</strong> <strong>Needs</strong> <strong>of</strong> Haitian affected by <strong>the</strong> 12 th January<br />

earthquake was c<strong>on</strong>ducted between May 2010 and August 2010. This assessment aims at<br />

analyzing <strong>the</strong> interc<strong>on</strong>nectedness <strong>of</strong> emoti<strong>on</strong>al, social and cultural anthropological needs<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> earthquake survivors in Haiti, and look at <strong>the</strong>ir interrelati<strong>on</strong> at <strong>the</strong> individual,<br />

family, group and community levels, in order to provide viable informati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong><br />

devising <strong>of</strong> multidisciplinary, multilayered psychosocial programs.<br />

The assessment uses <strong>the</strong> Rapid Appraisal Procedures c<strong>on</strong>sistent with former <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

assessments.<br />

The tools used include:<br />

• A standard interview form for interviews with community’s stakeholders<br />

• A standard interview form for interviews with internati<strong>on</strong>al stakeholders<br />

• A standard interview guide, with discussi<strong>on</strong> points for interviews with<br />

displaced families<br />

• A list <strong>of</strong> self reported social c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> 6 items: Housing, Security,<br />

Scholarizati<strong>on</strong>, Social Life, Food, Water and Sanitati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

• A list <strong>of</strong> distress indicators, encompassing 28 items.<br />

• Focus groups: 2 focus groups with 20 Haitian families in 2 camps<br />

• Interviews with stakeholders: 42 key informants, including internati<strong>on</strong>al,<br />

nati<strong>on</strong>al and local stakeholders.<br />

8

Based <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Haitian cultural and anthropological c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s and <strong>the</strong> practical<br />

difficulty to interview individuals in camps without several members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family<br />

participating, <strong>the</strong> current assessment was designed to be c<strong>on</strong>ducted in a family setting,<br />

allowing collective resp<strong>on</strong>ses. Additi<strong>on</strong>ally <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> distress was not analyzed<br />

individually, but focusing <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> recurrence <strong>of</strong> certain indicators across members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

families, with <strong>the</strong> ultimate intenti<strong>on</strong> to assess <strong>the</strong> wellbeing <strong>of</strong> neighborhood and its<br />

social and emoti<strong>on</strong>al determinants and not individual pathologies.<br />

Quantitative aspects<br />

This study was administered to nine-hundred and fifty families in displacement camps<br />

throughout Haiti. Analysis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> data showed that am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 950 families interviewed,<br />

families with parents and two children were <strong>the</strong> most comm<strong>on</strong> (26.7%).The principal<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>dents to <strong>the</strong> interviews, usually <strong>the</strong> household, were women in 60.4% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cases<br />

(n=534) and men in <strong>the</strong> 39.6% (n=344) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> cases. The biggest number <strong>of</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>dents<br />

by far lives in Port-au-Prince (27%), followed by Peti<strong>on</strong> Ville (17%) and Delmas (13%).<br />

The average score <strong>of</strong> distress is 8.32/35 with headaches (74%) sleeping problems (60%),<br />

anxiety (56%), and fatigue (53%) being reported in more than half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> families<br />

interviewed.<br />

The highest distress level scores were found in Leogane (10.8), Cit e Soliel (9.6), Delmas<br />

(8.9) Croix des Boukets (8.69), G<strong>on</strong>aives(8.31) and Port au Prince (8.31) while <strong>the</strong> lowest<br />

in Grand Goave (3.0).<br />

32% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> families stated that at least <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>dents experienced at least <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> three major distress indicators (Panic attacks, serious withdrawal, or suicide<br />

attempts), with panic attacks being <strong>the</strong> most prevalent. There were <strong>on</strong>ly five cases, or<br />

0.72% <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>, in which all three were experienced in <strong>the</strong> same family or<br />

individual resp<strong>on</strong>dent.<br />

Results showed that <strong>the</strong> general level <strong>of</strong> distress is significantly correlated with poor<br />

access to food (p= 0.039

drown[ing] me” (17%). Terms like “Depressi<strong>on</strong>” (4.39%) and “Fear” (4.08%) are least<br />

comm<strong>on</strong>ly used.<br />

53.28% <strong>of</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>dents lost some<strong>on</strong>e during <strong>the</strong> earthquake. Am<strong>on</strong>g those, 62.5% have<br />

lost <strong>on</strong>e family member, 24% lost two family members and <strong>the</strong> remainder lost three or<br />

family members. A significant positive correlati<strong>on</strong> was found between death in <strong>the</strong> family<br />

and level <strong>of</strong> distress (p= 0.049 70%), health (61%),<br />

work (59.4%) and security (50.2%).<br />

Lack <strong>of</strong> access to health and social services was reported in 45.7% <strong>of</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>dents and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a significant correlati<strong>on</strong> between locati<strong>on</strong>s and access to health and social<br />

services ( p=0.000

<strong>the</strong>y are physically present in <strong>the</strong> household, <strong>the</strong>y are unable to work due to <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

disabilities (most comm<strong>on</strong>ly an amputati<strong>on</strong>). The relati<strong>on</strong>ship <strong>of</strong> parents with children<br />

was also affected as many families expressed that <strong>the</strong>y cannot c<strong>on</strong>trol <strong>the</strong>ir children<br />

anymore. Many families feel “ashamed that <strong>the</strong>y can’t send <strong>the</strong>ir children to school”,<br />

plus <strong>the</strong>y think that lack <strong>of</strong> schooling is at <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> structure in children’s<br />

life, and <strong>the</strong> reas<strong>on</strong> why some children now act like “delinquents.” The children in<br />

exchange expressed <strong>the</strong> need to spend more time with <strong>the</strong>ir families and friends from<br />

school.<br />

As for <strong>the</strong> enlarged family, according to <strong>the</strong> camps, resp<strong>on</strong>dents have praised <strong>the</strong> revival<br />

<strong>of</strong> Lakou system as <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir best protective achievements after <strong>the</strong> earthquake, or<br />

lamented <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong> Lakou was dissolved or not c<strong>on</strong>sidered in <strong>the</strong> organizati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> camp.<br />

Many resp<strong>on</strong>dents have lamented overcrowding, bringing to an unlimited and excessive<br />

need for socializati<strong>on</strong> as a problem, and also a detriment to hygiene and health. Moreover<br />

people reported a more aggressive behavior in <strong>the</strong>ir neighbors and <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> as a<br />

whole after <strong>the</strong> earthquake.<br />

People who have experienced death in <strong>the</strong>ir family have higher level <strong>of</strong> distress, and<br />

qualitative results suggest that lack <strong>of</strong> proper passage rituals may be <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main<br />

causes <strong>of</strong> this distress, related with guilt, preoccupati<strong>on</strong>s as to possible possessi<strong>on</strong>s, and<br />

retaliati<strong>on</strong> from <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>es, who did not receive proper burial. Lack <strong>of</strong> burial cerem<strong>on</strong>ies in<br />

<strong>the</strong> past make <strong>the</strong> families unwilling to practice new rituals, like funeral or weddings due<br />

to <strong>the</strong> guilt <strong>the</strong>y feel for n<strong>on</strong> being able to c<strong>on</strong>duct proper burial to <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>es deceased<br />

during <strong>the</strong> earthquake<br />

As to identify existing resilience mechanisms <strong>the</strong> results showed that <strong>the</strong> families usually<br />

refer to clergy, friend, prayers, community support, traditi<strong>on</strong>al remedies or community<br />

health centers. Families turn to God because, to many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>dents, “<strong>on</strong>ly He can<br />

predict <strong>the</strong> future”, “He is <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e to trust because He is <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e who knows <strong>the</strong><br />

future”. Some “fear <strong>the</strong> future look to God for guidance”. It is also noted that for some<br />

“all <strong>of</strong> our hope is placed in God.”<br />

Most reported coping mechanisms used by kids to resp<strong>on</strong>d to sadness or frustrati<strong>on</strong>s are<br />

going to bed, play music, talk with enlarged family members or read. Their favorite<br />

games are football, play stati<strong>on</strong>, play with dolls, play with legos, card games, video<br />

games, racing, dance.<br />

When asked to identify <strong>the</strong> main acti<strong>on</strong>s that could be taken to improve <strong>the</strong> overall<br />

wellbeing, <strong>the</strong> families mainly referred to employment opportunities and ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

development, basic services and cultural c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> and recreati<strong>on</strong>al activities.<br />

The children required to make a list <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most three precious wishes reported schooling,<br />

future and housing. Children and adolescent are c<strong>on</strong>cerned about <strong>the</strong> likeability to<br />

c<strong>on</strong>tinuing <strong>the</strong>ir educati<strong>on</strong>, and being able to fulfill <strong>the</strong>ir dreams (becoming a doctor, a<br />

nurse, a psychologists, serve God, lawyer, pediatrician…).<br />

The mapping <strong>of</strong> health and psychosocial services MHPSS in Haiti prepared by <strong>the</strong> IASC<br />

group revealed some significant gaps. These were mainly related to <strong>the</strong> overemphasis <strong>on</strong><br />

11

psychological resp<strong>on</strong>ses (e.g. individual and group counseling) and <strong>the</strong> insufficient focus<br />

<strong>on</strong> social and community-based resp<strong>on</strong>ses. In additi<strong>on</strong> to that, <strong>the</strong>re is a lack/insufficient<br />

provisi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> specialized services.<br />

Organizati<strong>on</strong>s providing psychosocial and/or counseling services include:<br />

- Local organizati<strong>on</strong>s: Centre de Trauma, Centre Psychiatrique Mars & Klien, Saj<br />

associati<strong>on</strong>, Haiti Tchaka dance, Plastimun, Kore Timun foundati<strong>on</strong>, Group Interventi<strong>on</strong><br />

for children, Comite de la Cour des Enfants de Quettsar, Center Marie Denise Claude,<br />

Center D’ Educati<strong>on</strong> Populaire, Partners in Health.<br />

- Internati<strong>on</strong>al Organizati<strong>on</strong>s: <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>, ACF, ADRA, AVSI, HI, IFRC, MSF-Belgium, MSF-<br />

ES, MSF-H, Red Cross-France, WV, Red Cross NorCan ERU, MSF-Belgium, MSF-ES,<br />

MSF-Holland, Terre des Hommes, UNICEF, World Visi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Recommendati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

a) To enhance access to food in areas where distributi<strong>on</strong> is not up<strong>on</strong> standards since this<br />

is a significant source <strong>of</strong> distress.<br />

b) To enhance protective elements in <strong>the</strong> camps and prevent gender based violence. A<br />

reorganizati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> camps across lakou lines, both in terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> allocated<br />

in <strong>the</strong>m and <strong>the</strong> physical organizati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spaces in courtyards, could be a fast soluti<strong>on</strong><br />

to <strong>the</strong> immediate problems <strong>of</strong> overcrowding, safety, protecti<strong>on</strong> towards GBV and o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

possible violent behaviors in <strong>the</strong> camps.<br />

c) To provide safe, well lit spaces for socializati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> camps and structured activities.<br />

c) To provide durable housing soluti<strong>on</strong>s, that w<strong>on</strong>’t undermine <strong>the</strong> ec<strong>on</strong>omic and social<br />

life <strong>of</strong> residents due to distance from vital ec<strong>on</strong>omic and cultural centers, and respectful<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Lakou system<br />

d) To restore <strong>of</strong> a sense <strong>of</strong> legality and rule <strong>of</strong> law, possibly in a participatory<br />

community- based fashi<strong>on</strong>.<br />

e) To device and implement, in collaborati<strong>on</strong> between communities, religious and<br />

traditi<strong>on</strong>al religious leaders <strong>of</strong> a Country dedicated ritual funerary cerem<strong>on</strong>y, that could<br />

serve as definitive closure <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> issue <strong>of</strong> proper burial <strong>of</strong> corpses.<br />

f) To harm<strong>on</strong>ize <strong>the</strong> available services and communicate <strong>the</strong>ir availability in a transparent<br />

fashi<strong>on</strong>. It is recommended to establish or potentiate outreach-informati<strong>on</strong> teams,<br />

working in close collaborati<strong>on</strong> with cluster and governmental systems, and with camp<br />

authorities.<br />

g) To establish a newsletter for camp distributi<strong>on</strong> and radio ads <strong>on</strong> available psychosocial<br />

services.<br />

12

h) To establish a website <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> humanitarian agencies’ resources.<br />

i) To resp<strong>on</strong>d to <strong>the</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g term outcomes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> current situati<strong>on</strong>, building in service <strong>the</strong><br />

capacity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> country to resp<strong>on</strong>d, through <strong>the</strong> establishment <strong>of</strong> an in service master<br />

program in psychosocial resp<strong>on</strong>ses at <strong>the</strong> individual, family and community level, and <strong>the</strong><br />

creati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> a nati<strong>on</strong>al expert team.<br />

A part from <strong>the</strong> results <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study research, stakeholders formulated as series <strong>of</strong><br />

recommendati<strong>on</strong>s that are summarized here below<br />

• Culturally sensitive programs: <strong>Haitians</strong> have str<strong>on</strong>g attachment to cultural systems<br />

and values. MHPSS programmes should be community-based, family-focused and<br />

culturally-sensitive. The community should draw <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own resources to guide and<br />

lead MHPSS programming for sustainability<br />

• Avoid duplicati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> services: Organizati<strong>on</strong>s are c<strong>on</strong>centrating <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> same activities<br />

like child friendly spaces and group resp<strong>on</strong>ses, and in <strong>the</strong> area <strong>of</strong> Port Au Prince. Thus<br />

brings to duplicati<strong>on</strong> as well as produces several gaps, both geographical and in <strong>the</strong><br />

services provided.<br />

• Mental health Structure: Many organizati<strong>on</strong>s are c<strong>on</strong>centrating <strong>on</strong> psychosocial<br />

support and neglecting specialized mental health services. There is need to develop<br />

specialist psychiatric services for referral, and encompass traditi<strong>on</strong>al practices and transcultural<br />

models in <strong>the</strong> services.<br />

• Integrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> mental health in health: Mental health should be integrated with o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

medical outreach services. People living in areas hardly hit by <strong>the</strong> earthquake are<br />

suffering from all kinds <strong>of</strong> lingering maladies such as lost limbs, broken legs, eye and ear<br />

injuries as well as head injuries thus a need for integrati<strong>on</strong> to meet <strong>the</strong>se health needs<br />

exists.<br />

• Integrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> livelihood within psychosocial programs: Integrati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

psychosocial and livelihood programmes is advocated. MHPSS programmes are<br />

successful when invested within rebuilding local ec<strong>on</strong>omies. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, MHPSS<br />

programmes provide a multiplier effect <strong>on</strong> livelihood programmes.<br />

• Child Protecti<strong>on</strong>: child protecti<strong>on</strong> is to be included in any psychosocial structure<br />

due to vulnerability <strong>of</strong> children and <strong>the</strong>ir situati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> country even before <strong>the</strong><br />

earthquake.<br />

• Maintain mobile teams: Maintaining mobile clinics that address health isuues, o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

addressing mental health issues, and psychosocial mobile teams due to lack <strong>of</strong> physical<br />

structures mainly in suburb and faraway communes.<br />

• Introducing psychosocial support modules in all primary and sec<strong>on</strong>dary<br />

schools, in additi<strong>on</strong> to specialized courses (<strong>on</strong> psychosocial resp<strong>on</strong>se in<br />

emergency settings) at universities to enhance local capacities in resp<strong>on</strong>ding to<br />

emergencies.<br />

• Launching awareness campaigns regarding <strong>the</strong> importance <strong>of</strong> mental health and<br />

psychosocial support/ wellbeing.<br />

13

I. INTRODUCTION<br />

The 12 January earthquake which struck <strong>the</strong> Haitian coast, followed by several o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

aftershocks, has greatly damaged various cities in Haiti. At <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> August 2010, <strong>the</strong><br />

government and humanitarian community estimated that over 2 milli<strong>on</strong> people had been<br />

affected, 222,570 individuals died, with an estimated 80,000 corpses still missing;<br />

188,383 houses were destroyed or partially damaged, and 1.5 milli<strong>on</strong> pers<strong>on</strong>s were still<br />

displaced in 1,368 settlement sites (OCHA-Humanitarian Bullettin, 30 th July 2010). Most<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se families are still living in tents or self-made shelters c<strong>on</strong>structed from tarpaulin<br />

and wood. Service delivery to <strong>the</strong>se sites remains limited with <strong>the</strong> majority <strong>of</strong> efforts<br />

focused <strong>on</strong> addressing immediate needs in camps.<br />

9,000 individuals <strong>on</strong>ly, identified as being at high risk <strong>of</strong> dangerous flooding, have been<br />

relocated to <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly land identified by <strong>the</strong> government by <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong> September 2010,<br />

while some land owners and schools have started evicting <strong>the</strong> displaced. Surveys have<br />

indicated that whilst some 40% <strong>of</strong> homes remain intact, many people are unwilling to<br />

return to <strong>the</strong>ir home or property due to both fear <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r earthquake, and <strong>the</strong> fear <strong>of</strong><br />

loosing <strong>the</strong> services currently provided in <strong>the</strong> camps (UNOPS- Safe Shelter Strategy, 14 Th<br />

April, 2010).<br />

Agencies working within <strong>the</strong> humanitarian cluster tasked with Shelter c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> have<br />

provided 6,868 transiti<strong>on</strong>al shelters to more than 34,000 individuals up to September<br />

2010 (OCHA Humanitarian Bulletin, 30 July 2010). The Government <strong>of</strong> Haiti is<br />

encouraging IDPs to return to <strong>the</strong>ir homes, but <strong>the</strong>se efforts have so far yielded few<br />

results.<br />

<strong>Psychosocial</strong> Wellbeing and Mental Health in Emergency Displacement<br />

Displacement due to natural disasters requires major adaptati<strong>on</strong>s, as people need to<br />

redefine pers<strong>on</strong>al, interpers<strong>on</strong>al, socio-ec<strong>on</strong>omic, urban and geographic boundaries. This<br />

implies a redefiniti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> individual, familiar, group, and collective identities, roles and<br />

systems, and may represent an upheaval and a source <strong>of</strong> stress for <strong>the</strong> individual, <strong>the</strong><br />

family and <strong>the</strong> communities involved.<br />

Natural disaster-related displacement is accompanied by several stressors that include<br />

ec<strong>on</strong>omic c<strong>on</strong>straints, security issues, breakdown <strong>of</strong> social and primary ec<strong>on</strong>omic<br />

structures and c<strong>on</strong>sequent devaluati<strong>on</strong> or modificati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> social roles, and loss <strong>of</strong> loved<br />

<strong>on</strong>es. Moreover, instable and precarious life c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, including difficult access to<br />

services toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>of</strong> <strong>on</strong>e’s own social envir<strong>on</strong>ment and systems <strong>of</strong> meaning,<br />

and gaps in <strong>the</strong> rule <strong>of</strong> law, all c<strong>on</strong>tribute to create a very uncertain future.<br />

Often <strong>the</strong>se elements bring about a series <strong>of</strong> feelings, including grief, loss, and guiltiness<br />

towards <strong>the</strong> people who did not survive or o<strong>the</strong>r members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family, a sense <strong>of</strong><br />

inferiority, isolati<strong>on</strong>, sadness, anger, angst, insecurity and instability. These reacti<strong>on</strong>s<br />

14

caused by objective stress factors are generally not <strong>of</strong> psychopathological c<strong>on</strong>cern, and<br />

<strong>on</strong>ly in a very limited number <strong>of</strong> cases evolve in post-traumatic occurrences, making<br />

people unable to functi<strong>on</strong> (IASC 2007). However, providing psychosocial assistance in<br />

educati<strong>on</strong>al, cultural, community, religious and primary health setting aims at reducing<br />

psychosocial vulnerabilities and preventing <strong>the</strong>ir standstill which may in turn result in<br />

l<strong>on</strong>g-term mental problems and social dysfuncti<strong>on</strong>s (EU 2001; <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>, 2010).<br />

This assessment aims at analyzing <strong>the</strong> interc<strong>on</strong>nectedness <strong>of</strong> emoti<strong>on</strong>al, social and<br />

cultural anthropological needs am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> earthquake survivors in Haiti, and look at <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

interrelati<strong>on</strong> at <strong>the</strong> individual, family, group and community levels, in order to provide<br />

viable informati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> devising <strong>of</strong> multidisciplinary, multilayered psychosocial<br />

programs.<br />

The Haitian C<strong>on</strong>text<br />

No comprehensive psychosocial needs assessment was c<strong>on</strong>ducted in Haiti in <strong>the</strong> m<strong>on</strong>ths<br />

following <strong>the</strong> disaster, due to capacity c<strong>on</strong>straints and <strong>the</strong> impossibility to derive credible<br />

statistical results, given to <strong>the</strong> interrelati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> too many factors. However, <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

c<strong>on</strong>ducted in <strong>the</strong> immediate aftermath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> event a very qualitative evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

psychosocial needs, resilience factors to respect and facilitate, and developments<br />

activated by <strong>the</strong> adversity <strong>on</strong> which to build <strong>the</strong> psychosocial resp<strong>on</strong>ses <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> individual,<br />

family, group, and community levels, through brainstorming with community leaders,<br />

academics, students <strong>of</strong> psychology, religious leaders, mental health and psychosocial<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>als. This process involved around 200 individuals <strong>of</strong> both sexes- aged 22 to 82-<br />

many <strong>of</strong> which living or operating in camps. The instrument used was an adaptati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Renos Papadopoulos’ systemic grid (Papadopoulos, 2002). The main results are<br />

categorized in chart 1.<br />

15

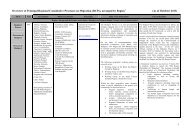

Outline <strong>of</strong> c<strong>on</strong>sequences and implicati<strong>on</strong>s (adapted from Renos Papadopoulos)<br />

Suffering<br />

Depressi<strong>on</strong>, anxiety<br />

Ordinary human suffering<br />

Default c<strong>on</strong>sequences<br />

Resilience<br />

Adversity’s Activated<br />

Development<br />

Individual<br />

Family<br />

Group<br />

identified<br />

as religious<br />

c<strong>on</strong>gregati<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

neighbourhood<br />

and<br />

colleagues)<br />

Society<br />

a) n<strong>on</strong> clinical depressi<strong>on</strong><br />

c) anxieties<br />

d) powerlessness<br />

e) fears for <strong>the</strong> future<br />

socioec<strong>on</strong>omic life<br />

f) fears <strong>of</strong> ano<strong>the</strong>r disaster<br />

g) guilt towards <strong>the</strong> dead<br />

h) guilt towards <strong>the</strong> community<br />

i) guilt driven by <strong>the</strong> belief that <strong>the</strong><br />

disaster was a punishment<br />

from God<br />

or Lwas<br />

l) sense <strong>of</strong> anger and frustrati<strong>on</strong> due<br />

to <strong>the</strong> poor services received and <strong>the</strong><br />

disinformati<strong>on</strong> about settlement<br />

plans<br />

a) loss <strong>of</strong> loved <strong>on</strong>es<br />

b) separati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

aband<strong>on</strong>ment<br />

c) challenges to traditi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

family roles<br />

d) hyper-protecti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> children<br />

e) increase in stress and violence<br />

f) loss <strong>of</strong> bel<strong>on</strong>gings and memories<br />

a) withdrawal<br />

b) c<strong>on</strong>fusi<strong>on</strong><br />

c) disorganizati<strong>on</strong><br />

d) loss <strong>of</strong> members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> group<br />

e) disorientati<strong>on</strong>s<br />

a) loss <strong>of</strong> lives, leaders, experts<br />

b) destructi<strong>on</strong> and loss <strong>of</strong> cultural<br />

heritage<br />

c) enhancement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “aid culture”<br />

d) polluti<strong>on</strong> and poor envir<strong>on</strong>mental<br />

health<br />

e) fears and paranoia related with <strong>the</strong><br />

presence <strong>of</strong> foreigners, especially in<br />

relati<strong>on</strong> to cultural col<strong>on</strong>ialism and<br />

political c<strong>on</strong>trol<br />

f) redefiniti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> geographical and<br />

urbanistic boundaries<br />

g) Exacerbati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> existing sociocultural<br />

divides and fears <strong>of</strong> future<br />

social tensi<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

a) religi<strong>on</strong><br />

b) refer to <strong>the</strong> collectivity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

experience<br />

c) getting organized to help <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

d) reviving social life<br />

e) creative activities, including ritual<br />

dances<br />

and s<strong>on</strong>gs<br />

a) revival <strong>of</strong> family support and lakou<br />

systems<br />

b) trans-generati<strong>on</strong>al support<br />

c) solidarity<br />

d) sharing <strong>of</strong> emoti<strong>on</strong>al experiences<br />

within<br />

<strong>the</strong> family<br />

e) neighbourhood support<br />

a) sharing experiences<br />

b) religious rituals<br />

c)intellectualizati<strong>on</strong>/rati<strong>on</strong>alizati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> experience<br />

d) activati<strong>on</strong> to help <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

a) hope<br />

b) religious beliefs and explanatory<br />

models<br />

c) aid<br />

d) referral to cultural and artistic life<br />

e) banalizing <strong>the</strong> experience<br />

a) renewed sense <strong>of</strong> being part <strong>of</strong> a<br />

collectivity<br />

b) pers<strong>on</strong>al organizati<strong>on</strong>al and<br />

solidarity skills<br />

c) str<strong>on</strong>ger coping mechanism than<br />

expected<br />

a) increased trust<br />

b) increased sensitivity and<br />

listening<br />

c) increased respect<br />

d) increased physical nurturing<br />

a) a more participatory approach<br />

to group<br />

leadership and decisi<strong>on</strong> making<br />

b) new sp<strong>on</strong>taneous affiliati<strong>on</strong><br />

c) groups becoming more<br />

inclusive<br />

d) community based security<br />

systems organized<br />

a) str<strong>on</strong>ger nati<strong>on</strong>al sense<br />

b) more critical political sense<br />

c) acknowledgement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

necessity to rec<strong>on</strong>struct<br />

better than before, <strong>on</strong> multiple<br />

levels<br />

d) reciprocity<br />

e) solidarity<br />

f) increased sense <strong>of</strong> community<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>sibility<br />

g) increase in volunteerism<br />

16

On <strong>the</strong> individual wound level, <strong>the</strong> informal reports collected from <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>, IMC, Hi Tech,<br />

MdM, IFRC and o<strong>the</strong>r agencies, which have acted since <strong>the</strong> aftermath <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> disaster <strong>on</strong><br />

providing specialized mental health services, would suggest an epiphenomenal incidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> post traumatic reacti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> clinical c<strong>on</strong>cern. The outpatient psychiatric clinic Mars and<br />

Kline in Port Au Prince received in <strong>the</strong> first 6 weeks after <strong>the</strong> events every day an<br />

estimate <strong>of</strong> up to 100 cases (IMC, unpublished) with different problems including<br />

epilepsy, pre-existing disorders but also anxieties, or medical problems <strong>of</strong> unknown<br />

causes, such as possibly psychosomatic reacti<strong>on</strong>s. IMC which was operating in <strong>the</strong><br />

above-menti<strong>on</strong>ed hospital as well as in additi<strong>on</strong>al six clinics identified through its very<br />

qualified psychiatric staff less than 50 severely distressed cases <strong>on</strong>ly, in 6 weeks <strong>of</strong><br />

activity. <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g> psychosocial teams, active in 19 camps, referred for specialized services 14<br />

individuals <strong>on</strong>ly in <strong>the</strong> first 4 m<strong>on</strong>ths after <strong>the</strong> disaster. In both cases, <strong>the</strong>se were mainly<br />

pre-existing psychiatric cases, or females subject to individual assaults, and severely<br />

physically traumatized individuals, including people suffering from amputati<strong>on</strong>s and<br />

burns.<br />

The participants’ generated resp<strong>on</strong>ses to this initial brainstorming validated from a field<br />

perspective relevant outcomes <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature review c<strong>on</strong>ducted by <strong>the</strong> McGill<br />

University so<strong>on</strong> after <strong>the</strong> disaster (McGill, 2010). Since some <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se findings inform <strong>the</strong><br />

rati<strong>on</strong>ale, items and methods <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> current assessment, <strong>the</strong>y are listed below.<br />

Family and lakou<br />

Family is <strong>of</strong> primary importance in <strong>the</strong> Haitian social system (Craan, 2002; Nicolas,<br />

Swartz et Pierre, 2009, Mc Gill 2010), and is more flexible and extended than in Western<br />

societies, encompassing far family members, several generati<strong>on</strong>s, neighbors and friends.<br />

Prior to <strong>the</strong> 20th Century, and still today in <strong>the</strong> most rural societies, families were<br />

organized around <strong>the</strong> lakou, which defines both <strong>the</strong> courtyard around which <strong>the</strong> members<br />

<strong>of</strong> an extended family live, and <strong>the</strong> extended family itself (Nicolas, Schwartz, et Pierre,<br />

2009, Edm<strong>on</strong>d, Randoplh et Richard, 2007). While this c<strong>on</strong>cept has been challenged in<br />

<strong>the</strong> last Century, and especially after <strong>the</strong> Eighties by massive urbanizati<strong>on</strong>, migrati<strong>on</strong>,<br />

disaggregati<strong>on</strong>, <strong>the</strong> anthropological dimensi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> lakou is still at <strong>the</strong> fundaments <strong>of</strong><br />

Haitian society (Mc Gill, 2010). Urbanized communities, by instance, tend to recreate it,<br />

as much as possible in <strong>the</strong> urban suburbs, and include people coming from <strong>the</strong> same rural<br />

districts in it. The same happens am<strong>on</strong>g University students moving to PauP to study.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>dents to <strong>the</strong> initial brainstorming highlighted <strong>the</strong> revitalizati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

lakou system after <strong>the</strong> earthquake as <strong>on</strong>e <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> main resilience factors, and this is<br />

trivially evident in <strong>the</strong> camps, since camp inhabitants tend to create aggregati<strong>on</strong>s across<br />

lakou lines.<br />

Based <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>se anthropological c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>s, and <strong>the</strong> practical difficulty to interview<br />

individuals in camps without several members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> family participating, <strong>the</strong> current<br />

assessment was designed to be c<strong>on</strong>ducted in a family setting, allowing collective<br />

resp<strong>on</strong>ses. Additi<strong>on</strong>ally <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> distress was not analyzed individually, but focusing<br />

<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> recurrence <strong>of</strong> certain indicators across members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> families, with <strong>the</strong> ultimate<br />

intenti<strong>on</strong> to assess <strong>the</strong> wellbeing <strong>of</strong> a neighborhood and its social and emoti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

determinants, and not individual pathologies.<br />

17

Religi<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cept <strong>of</strong> identity<br />

Religi<strong>on</strong> plays a crucial role in <strong>the</strong> definiti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> individual and collective identities in<br />

Haiti, and in providing explanatory models to natural disasters. As such it was reported as<br />

a crucial resilience and resp<strong>on</strong>se factor by <strong>the</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>dents to <strong>the</strong> first brainstorming. 80%<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> self define as Roman Catholics and 20% circa as Protestants, but people<br />

from lower classes, and <strong>the</strong>refore <strong>the</strong> big majority <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> camps inhabitants are likely to<br />

adhere exclusively, or in combinati<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r religi<strong>on</strong>s to Voodoo (Gopaul<br />

McNicol et ali, 1998; McGill, 2010). The Voodoo is c<strong>on</strong>sidered as a religi<strong>on</strong> because it<br />

is based <strong>on</strong> rituals, cerem<strong>on</strong>ies and acts through which <strong>the</strong> individual enters in a relati<strong>on</strong><br />

with <strong>the</strong> divine. It is <strong>on</strong>ly in 1911, that <strong>the</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g standing practices <strong>of</strong> Vodoo were<br />

etymologically related to <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cept <strong>of</strong> vodun, that is “god”, a “spirit” or its “image”<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> F<strong>on</strong> tribes <strong>of</strong> Dahomey and Togo(Materaux, 1958). Hougan, <strong>the</strong> Vodoo<br />

celebrator, in Dahomenyan means “master <strong>of</strong> God”. (Fils-aimé 2007).<br />

C<strong>on</strong>sistently with Vodoo beliefs and practices, identity in <strong>the</strong> Haitian traditi<strong>on</strong>al culture is<br />

anthropologically characterized by a cosmos-centric ra<strong>the</strong>r than anthropocentric visi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> self. Wellbeing results indeed form <strong>the</strong> harm<strong>on</strong>y that an individual is able to create<br />

with his her c<strong>on</strong>text and <strong>the</strong> natural world, which encompasses a multitude <strong>of</strong> spirits,<br />

ancestors, and materializati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> so-called “invisible” (Brodwin, 1992). The<br />

brainstorming’s results highlighted how <strong>the</strong> challenges brought to <strong>the</strong> individual identity<br />

by <strong>the</strong> natural disaster, are in fact mitigated by <strong>the</strong> collective fashi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> experience<br />

and its adherence to a natural cycle. C<strong>on</strong>sistently, <strong>the</strong> current assessment looked at<br />

challenges faced by <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> individual, family and community level, and at<br />

identifying existing explanatory systems and collective resilience factors.<br />

Grief and o<strong>the</strong>r determinants <strong>of</strong> uneasiness<br />

In <strong>the</strong> first brainstorming, death <strong>of</strong> significant o<strong>the</strong>rs was not reported am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> main<br />

causes <strong>of</strong> individual distress, but it became a significant challenge in <strong>the</strong> family and<br />

societal wellness, mainly due to <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> reference pers<strong>on</strong>s.<br />

A possible explanati<strong>on</strong> can be found in <strong>the</strong> fact that in Vodoo <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> spirits,<br />

ancestors and deceased is strictly linked with <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> living. The lwas, such as<br />

<strong>the</strong> spirits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> African ancestors, divided in Ginen (<strong>the</strong> positive lwas), Rada, and Petros<br />

(<strong>the</strong> fighting spirits, including Makaya and Bumba) in fact directly influence <strong>the</strong> social<br />

and emoti<strong>on</strong>al wellness <strong>of</strong> families and individuals, as <strong>the</strong> spirits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deceased family<br />

members do. The relati<strong>on</strong> that exists between <strong>the</strong> Lwa that possesses a human and <strong>the</strong><br />

human himself is that <strong>of</strong> “<strong>the</strong> horse rider and his horse”, as in <strong>the</strong> popular saying “The<br />

Lwa seized his horse” (Metraux 1958). Moreover, practices <strong>of</strong> white and black magic<br />

include <strong>the</strong> possibility for Vodoo practiti<strong>on</strong>ers to revive <strong>the</strong> z<strong>on</strong>bi (soul) <strong>of</strong> dead pers<strong>on</strong>s,<br />

ei<strong>the</strong>r in <strong>the</strong> form <strong>of</strong> living corpses or sending <strong>the</strong> air or <strong>the</strong> soul <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> deceased to<br />

possess an individual, who will <strong>the</strong>refore assume characteristics and behaviour proper <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> individual <strong>the</strong> air or <strong>the</strong> z<strong>on</strong>bi bel<strong>on</strong>ged to. Through <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> clay urns, called govi,<br />

<strong>the</strong> voodoo practiti<strong>on</strong>ers can also establish a c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> and communicati<strong>on</strong> between <strong>the</strong><br />

living and <strong>the</strong> dead.<br />

18

Such a close emoti<strong>on</strong>al and affective relati<strong>on</strong> between <strong>the</strong> world <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> living and <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>e<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dead, may reduce <strong>the</strong> distress provoked by grief and make death <strong>of</strong> significant<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs an acceptable experience <strong>on</strong> an individual level. Therefore, and c<strong>on</strong>sistently with a<br />

psychosocial approach, this assessment did not imply a default relati<strong>on</strong> between distress<br />

and magnitude <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> losses due to <strong>the</strong> earthquake but analyzed <strong>the</strong> levels <strong>of</strong> distress with<br />

magnitude <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> losses as well as problems <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> present, including de-locati<strong>on</strong>, food<br />

provisi<strong>on</strong>, type <strong>of</strong> housing, security in <strong>the</strong> camps and socioec<strong>on</strong>omic status, to try to<br />

identify what predicts <strong>the</strong> most.<br />

Determinants <strong>of</strong> access to mental health<br />

Half <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Haitians</strong> do not have access to formal healthcare (CCMU, 2006). The rural<br />

populati<strong>on</strong> mainly accesses primary health care through faith-based NGOs and traditi<strong>on</strong>al<br />

healers. Am<strong>on</strong>g all classes, emoti<strong>on</strong>al matters, and psychiatric uneasiness are dealt within<br />

<strong>the</strong> family or <strong>the</strong> religious c<strong>on</strong>text. Lower class <strong>Haitians</strong> will generally seek help from<br />

houngan, and a mental health pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>on</strong>ly if behavior is already unacceptable for<br />

<strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>text. Upper class <strong>Haitians</strong> are more likely to refer to a combinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> herbalist<br />

care and prayers (Mc Gill, 2010)<br />

More serious forms <strong>of</strong> depressi<strong>on</strong> am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lower classes are likely to be associated<br />

with spell or possessi<strong>on</strong>. In <strong>the</strong>se cases, Vodoo practiti<strong>on</strong>ers are involved and community<br />

cerem<strong>on</strong>ies are celebrated to heal <strong>the</strong> possessi<strong>on</strong>s. If <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> is freed by <strong>the</strong> spirit, heshe<br />

can be initiated to <strong>the</strong> Vodoo priesthood. Therefore possessi<strong>on</strong> may bring to a higher<br />

level in society and <strong>the</strong> discriminati<strong>on</strong> between <strong>the</strong> pers<strong>on</strong> and <strong>the</strong> possessing spirit brings<br />

to <strong>the</strong> attributi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “problem” to <strong>the</strong> entity and not to <strong>the</strong> individual, reducing<br />

stigmatizati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

Prior to <strong>the</strong> last disasters, western psychiatric and psychological c<strong>on</strong>cepts <strong>of</strong> mental<br />

health have not been priority for <strong>the</strong> Haitian government, nei<strong>the</strong>r have been popular<br />

am<strong>on</strong>g <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>, and a nati<strong>on</strong>al mental health strategy is missing. 11 to 20<br />

psychiatrists are accounted in <strong>the</strong> Country, <strong>of</strong> which 7 working for <strong>the</strong> public sector<br />

(PAHO, 2010), and 2 psychiatric hospitals exist in Port au Prince, <strong>the</strong> Mars and Kline for<br />

acute cases, with a capacity <strong>of</strong> 100 beds, and <strong>the</strong> Defilee de Beudet for mainly chr<strong>on</strong>ic<br />

cases, with a former capacity <strong>of</strong> up to 180 beds, and a current capacity <strong>of</strong> 50 transiti<strong>on</strong>al<br />

shelters c<strong>on</strong>structed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

In this respect, <strong>the</strong> assessment tried to be respectful <strong>of</strong> existing belief systems, avoiding<br />

pathologizati<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong> rati<strong>on</strong>al <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> study, <strong>the</strong> semantic <strong>the</strong> terminology adopted and in<br />

<strong>the</strong> interviews procedures and setting.<br />

19

II.<br />

METHODS<br />

The assessment was c<strong>on</strong>ducted between May 2010 and August 2010, with <strong>the</strong> aim to<br />

identify <strong>the</strong> general level <strong>of</strong> distress in <strong>the</strong> populati<strong>on</strong>, to highlight its possible sources<br />

and list existing coping mechanisms to enhance and support. The quantitative part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

assessment in particular, tried to prioritize locati<strong>on</strong>s and <strong>the</strong>matic sectors <strong>of</strong> interventi<strong>on</strong>,<br />

based <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> correlati<strong>on</strong>s between levels <strong>of</strong> distress, geographical distributi<strong>on</strong> and certain<br />

social indicators.<br />

Objectives<br />

The assessment objectives are a) to provide all humanitarian actors with informati<strong>on</strong> and<br />

insights that can make <strong>the</strong>m more psychosocial sensitive and aware, while providing<br />

assistance, and b) to help psychosocial pr<strong>of</strong>essi<strong>on</strong>als to c<strong>on</strong>ceive specific psychosocial<br />

programs targeting <strong>the</strong> psychosocial c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> internally displaced <strong>Haitians</strong>. More<br />

specifically, <strong>the</strong> study aims at identifying correlati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>of</strong> distress with geographical<br />

locati<strong>on</strong>s and social c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, and to qualitatively look at existing coping mechanisms<br />

and possible resp<strong>on</strong>ses.<br />

Study type<br />

Logistical and capacity c<strong>on</strong>straints made it impossible to c<strong>on</strong>duct a detailed assessment.<br />

It was <strong>the</strong>refore decided to use Rapid Appraisal Procedures for <strong>the</strong> following reas<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

• C<strong>on</strong>sistency with former <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g> assessments. The assessment <strong>on</strong> “<strong>Psychosocial</strong><br />

Status <strong>of</strong> IDPs Communities in Iraq” (<str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>; 2006) brought to <strong>the</strong> elaborati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

appropriate assessment tools, which were readapted for <strong>the</strong> current assessment.<br />

The same tools were successfully re-adapted and used for an assessment <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

“<strong>Psychosocial</strong> <strong>Needs</strong> <strong>of</strong> Displaced and Returnees Communities in Leban<strong>on</strong><br />

Following <strong>the</strong> War Events”, (<str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>; 2006), <strong>the</strong> ”<str<strong>on</strong>g>Assessment</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> <strong>Psychosocial</strong><br />

<strong>Needs</strong> <strong>of</strong> Iraqis Displaced in Jordan and Leban<strong>on</strong>” (<str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>, 2008) and smaller scale<br />

initiatives in DRC and Kenya.<br />

• Flexibility. Relying <strong>on</strong> multiple sources whose weight may vary according to <strong>the</strong><br />

circumstances, it guarantees a wide degree <strong>of</strong> flexibility, within a scientific<br />

c<strong>on</strong>text.<br />

• Relevance. Its approach is holistic and includes evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> existing initiatives<br />

in <strong>the</strong> field. In additi<strong>on</strong>, it gives importance to local knowledge including <strong>the</strong><br />

beneficiaries’ evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong>. The RAP approach is likely to avoid<br />

prejudgments <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> situati<strong>on</strong> under analysis.<br />

• Participatory process. It allows interviewers to c<strong>on</strong>tribute in <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong><br />

reviewing and adapting <strong>the</strong> tools, according to <strong>the</strong>ir understanding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> specifics<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> local community.<br />

• Rapidity. It allows c<strong>on</strong>ducting a scientific based assessment in a limited period <strong>of</strong><br />

time, and allows a qualitative as well as quantitative analysis <strong>of</strong> results. This last<br />

20

element is crucial, given <strong>the</strong> combinati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> large numbers <strong>of</strong> displaced, and a<br />

limited budget, which would make a large scale quantitative survey impossible.<br />

Tools<br />

The tools include:<br />

A standard form for interviews with community’s stakeholders and a standard form for<br />

interviews with internati<strong>on</strong>al stakeholders.<br />

Both interviews aim at receiving informati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> 1) <strong>the</strong> local understanding <strong>of</strong><br />

psychosocial c<strong>on</strong>cepts and related resp<strong>on</strong>se systems 2) existing psychosocial trainings,<br />

services and activities; 3) <strong>the</strong> stakeholders’ perspective <strong>on</strong> priority needs <strong>of</strong> displaced<br />

<strong>Haitians</strong>; 4) stakeholders’ plans and suggesti<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>cerning strategies to be implemented.<br />

All questi<strong>on</strong>s are open ended, and <strong>the</strong> results are read in a qualitative way.<br />

A standard interview, for displaced families.<br />

The 57 questi<strong>on</strong>s are clustered <strong>on</strong> eight groups: living c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s, household list,<br />

families’ understanding and definiti<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> psychosocial needs and c<strong>on</strong>cepts, <strong>the</strong> family’s<br />

view <strong>on</strong> existing coping mechanism, and <strong>the</strong>ir evaluati<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> provisi<strong>on</strong> <strong>of</strong> services,<br />

psychosocial needs self-assessment, resp<strong>on</strong>se, including suggesti<strong>on</strong>s for future<br />

programming and finally a focus <strong>on</strong> children. The questi<strong>on</strong>s and items, originally<br />

developed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>IOM</str<strong>on</strong>g>, were reviewed 3 times by a global interagency committee, by<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essors <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> faculties <strong>of</strong> Human Sciences and Ethnology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Haiti,<br />

and by <strong>the</strong> group <strong>of</strong> Haitian practiti<strong>on</strong>ers, who participated to a training <strong>of</strong> trainers (ToT)<br />

in Port Au Prince, to guarantee cultural and interagency appropriateness. The<br />

questi<strong>on</strong>naire is compiled by <strong>the</strong> interviewer thanks to a guided discussi<strong>on</strong> with <strong>the</strong><br />

interviewees, during which questi<strong>on</strong>s d<strong>on</strong>’t have to be resp<strong>on</strong>ded chr<strong>on</strong>ologically. The<br />

discussi<strong>on</strong>s are c<strong>on</strong>ducted with all members <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> families, who are willing to<br />

participate. However, for each questi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong>e resp<strong>on</strong>se <strong>on</strong>ly is to be agreed per household.<br />

The questi<strong>on</strong>s are both closed and open ended and are read both in a quantitative and a<br />

qualitative fashi<strong>on</strong>. In particular, <strong>the</strong> most recurrent answers to certain items were<br />

computed to analyze descriptive statistics and possible correlati<strong>on</strong>s with <strong>the</strong> items below.<br />

A family well-being list<br />

A measure quantifying <strong>the</strong> self-reported satisfacti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> 6 basic social c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

Housing, Security, Scholarizati<strong>on</strong>, Social Life, Food, Water and Sanitati<strong>on</strong>, is compiled<br />

by <strong>the</strong> interviewer while discussing with <strong>the</strong> family (Annex IV)<br />

1. Housing: For housing <strong>the</strong> family is asked whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>y are residing in <strong>the</strong>ir own<br />

house, in a rented <strong>on</strong>e , in a hosting family’s house, in a shelter, in a tent in camp<br />

or in a tent within <strong>the</strong> property <strong>of</strong> a hosting family or put in <strong>the</strong> neighborhood.<br />

21

Only <strong>on</strong>e resp<strong>on</strong>se opti<strong>on</strong> is allowed and each type <strong>of</strong> housing is numerically<br />

defined and computed.<br />

2. Security: Each family has to state if <strong>the</strong>y face <strong>on</strong>e or more issues am<strong>on</strong>g: fear <strong>of</strong><br />

disappearance <strong>of</strong> children; fear <strong>of</strong> rape; fear <strong>of</strong> being robbed; fear <strong>of</strong> being<br />