Aug - AmericanRadioHistory.Com

Aug - AmericanRadioHistory.Com

Aug - AmericanRadioHistory.Com

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

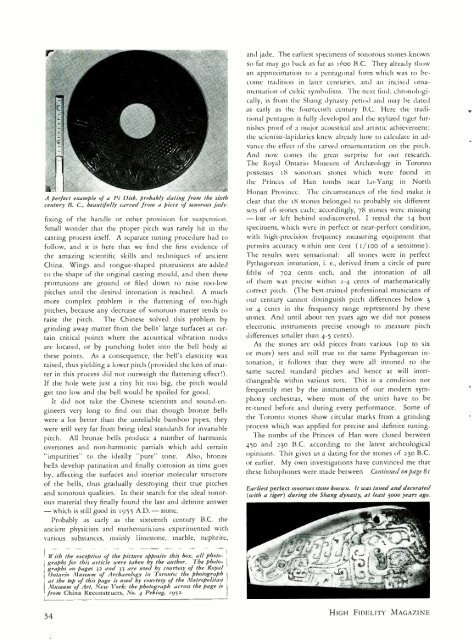

A perfect ,-.%ample of a Pi Disk, probably dating Jro,,, i/- sixth<br />

century B. C., beautifully carted from a piece f .v unrous jade.<br />

fixing of the handle or other provision for suspension.<br />

Small wonder that the proper pitch was rarely hit in the<br />

casting process itself. A separate tuning procedure had to<br />

follow, and it is here that we find the first evidence of<br />

the amazing scientific skills and techniques of ancient<br />

China. Wings and tongue -shaped protrusions are added<br />

to the shape of the original casting mould, and then these<br />

protrusions are ground or filed down to raise too -low<br />

pitches until the desired intonation is reached. A much<br />

more complex problem is the flattening of too -high<br />

pitches, because any decrease of sonorous matter tends to<br />

raise the pitch. The Chinese solved this problem by<br />

grinding away matter from the bells' large surfaces at certain<br />

critical points where the acoustical vibration nodes<br />

are located, or by punching holes into the bell body at<br />

these points. As a consequence, the bell's elasticity was<br />

raised, thus yielding a lower pitch (provided the loss of matter<br />

in this process did not outweigh the flattening effect!).<br />

If the hole were just a tiny bit too big, the pitch would<br />

get too low and the bell would he spoiled for good.<br />

It did not take the Chinese scientists and sound -engineers<br />

very long to find out that though bronze bells<br />

were a lot better than the unreliable bamboo pipes, they<br />

were still very far from being ideal standards for invariable<br />

pitch. All bronze bells produce a number of harmonic<br />

overtones and non- harmonic partials which add certain<br />

"impurities" to the ideally "pure" tone. Also, bronze<br />

bells develop patination and finally corrosion as time goes<br />

by, affecting the surfaces and interior molecular structure<br />

of the bells, thus gradually destroying their true pitches<br />

and sonorous qualities. In their search for the ideal sonorous<br />

material they finally found the last and definite answer<br />

-which is still good in 1955 A.D.- stone.<br />

Probably as early as the sixteenth century B.C. the<br />

ancient physicists and mathematicians experimented with<br />

various substances, mainly limestone, marble, nephrite,<br />

and jade. The earliest specimens of sonorous stones known<br />

so far may go hack as far as 1600 B.C. They already show<br />

an approximation to a pentagonal form which was to hecome<br />

tradition in later centuries, and an incised ornamentation<br />

of cultic symbolism. The next find, chronologically,<br />

is from the Shang dynasty period and may be dated<br />

as early as the fourteenth century B.C. Here the traditional<br />

pentagon is fully developed and the stylized tiger furnishes<br />

proof of a major acoustical and artistic achievement:<br />

the scientist -lapidaries knew already how to calculate in advance<br />

the effect of the carved ornamentation on the pitch.<br />

And now comes the great surprise for our research.<br />

The Royal Ontario Museum of Archæology in Toronto<br />

possesses 18 sonorous stones which were found in<br />

the Princes of Han tombs near Lo -Yang in North<br />

Honan Province. The circumstances of the find make it<br />

clear that the 18 stones belonged to probably six different<br />

sets of 16 stones each; accordingly, 78 stones were missing<br />

- lost or left behind undiscovered. I tested the 14 best<br />

specimens, which were in perfect or near -perfect condition,<br />

with high- precision frequency measuring equipment that<br />

permits accuracy within one cent (r /too of a semitone).<br />

The results were sensational: all stones were in perfect<br />

Pythagorean intonation, i. e., derived from a circle of pure<br />

fifths of 702 cents each, and the intonation of all<br />

of them was precise within 2 -4 cents of mathematically<br />

correct pitch. (The best -trained professional musicians of<br />

our century cannot distinguish pitch differences below 3<br />

or 4 cents in the frequency range represented by these<br />

stones. And until about ten years ago we did not possess<br />

electronic instruments precise enough to measure pitch<br />

differences smaller than 4 -5 cents).<br />

As the stones are odd pieces from various (up to six<br />

or more) sets and still true to the same Pythagorean intonation,<br />

it follows that they were all intoned to the<br />

same sacred standard pitches and hence at will interchangeable<br />

within various sets. This is a condition not<br />

frequently met by the instruments of our modern symphony<br />

orchestras, where most of the units have to be<br />

re -tuned before and during every performance. Some of<br />

the Toronto stones show circular marks from a grinding<br />

process which was applied for precise and definite tuning.<br />

The tombs of the Princes of Han were closed between<br />

45o and 230 B.C. according to the latest archeological<br />

opinions. This gives us a dating for the stones of 230 B.C.<br />

or earlier. My own investigations have convinced me that<br />

these lithophones were made between Continued on page 8i<br />

Earliest perfect sonorous stone known. It was tuned and decorated<br />

(with a tiger) during the Shang dynasty, at least 3000 years ago.<br />

With the exception of the picture opposite this box, all photographs<br />

for this article were taken by the author. The photographs<br />

on pages 32 and 33 are used by courtesy of the Royal<br />

Ontario Museum of Archaeology in Toronto; the photograph<br />

at the top of this page is used by courtesy of the Metropolitan<br />

Museum of Art, New York; the photograph across the page is<br />

from China Reconstructs, No. 4 Peking, 1952.<br />

34<br />

HIGH FIDELITY MAGAZINE