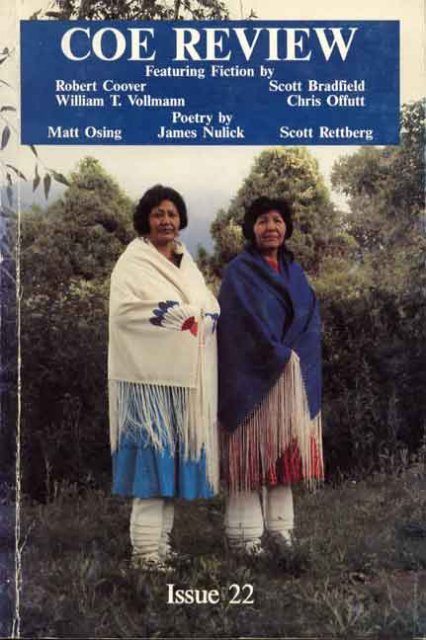

Issue 22 - 1992

Issue 22 - 1992

Issue 22 - 1992

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

COE REVIEW - <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong> - <strong>1992</strong><br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

James Nulick<br />

Senior Editor<br />

Scott Rettberg<br />

Business Manager<br />

Jen Beardsley<br />

Manuscript Readers<br />

Donald Berry<br />

Amy Bettinardi<br />

Nathan Forneris<br />

Chris Funk<br />

Kathryn O’Day<br />

Eric Rasmussen<br />

Faculty Advisor<br />

Charles Aukema<br />

Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to Coe Review, Coe<br />

College, 1<strong>22</strong>0 First Avenue N.E., Cedar Rapids, IA 52402. The editors invite<br />

submissions of fiction and poetry, which must be received between October 1 and<br />

March 31; manuscripts received between April 1 and September 30 will not be<br />

read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, selfaddressed<br />

envelope. All manuscripts become the property of Coe Review, unless<br />

otherwise indicated. Copyright © <strong>1992</strong> by Coe Review. No part of this volume<br />

may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views<br />

expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or<br />

sponsors. Printed in the United States by Linn-Litho.

Table of Contents<br />

Fiction<br />

Scott Bradfleld<br />

Closer To You<br />

Robert Coover<br />

Man Walking at 24 Frames Per Second<br />

The Titles Sequence<br />

Nancy Sweet<br />

J<br />

Matt Osing<br />

Tuna on White<br />

William T Volltnann<br />

The Blue Wallet<br />

Chris Offutt<br />

Blue Lick<br />

Andrew Mozina<br />

Timmy the Tubercular Seal:<br />

A Story inThree parts<br />

Donald Berry<br />

No Stranger<br />

Poetry<br />

Matt Osing<br />

Submission<br />

Mogan David Wine (serve very cold)<br />

Celine’s Mother’s Day<br />

James Nulick<br />

Sunday Barbecue<br />

Houseshoes<br />

Ten<br />

Scott Rettberg<br />

Sideshow Fat Man<br />

Mohawk Hangnail<br />

Last Night

R.D. Drexier<br />

Koan<br />

Religion<br />

Jacki Thomas<br />

Pyromaniac<br />

Lois Marie Harrod<br />

At the Mobil Station<br />

Lucinda Mason<br />

Happy Birthday!!<br />

A.C. Brocki<br />

Experience<br />

S. Ann Clark<br />

James’ Dad<br />

Kendy Wazac<br />

WashDay<br />

SonnetforaSon<br />

Barb Martens<br />

Choices<br />

Chris Funk<br />

Dr. Arbuckle<br />

Korean Massage Parlor<br />

Tracy Orand<br />

drawing profiles of the presidents on<br />

your naked butt sunday morning<br />

Mylinda Grinstead<br />

That Mocking Bird Won’t Sing<br />

Untitled<br />

Pete Lauf<br />

Walking with Brigitte after Taps in August<br />

Troy Headrick<br />

Ass and Assonance<br />

Alexa Fenske<br />

SixthMonth<br />

ForJames

For Cody Until I Get it Right<br />

Pamela Oberon Davis<br />

The Scaglione Strawberry Disaster<br />

Advice To New Poets<br />

Contnbutor’s Notes<br />

Cover photography by Bob Campagna<br />

Inside photography by Debbie Landey

Closer To You<br />

Scott Bradfield<br />

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

In the sunny mornings you chase the orange cat across the<br />

green grass. Underneath your feet the shelter, filled with the moon,<br />

the rain and the stars and the wind. And the orange cat lands on the<br />

fence, its orange tail twisting. Its dead sparrow on the crumbling<br />

brick barbecue. Big weeds from the barbecue, and the rusting iron<br />

gate and brown hollow snails all around. The dead sparrow says<br />

when you touch it. The yard says, the underground shelter says The<br />

underground shelter filled with everything that is not you. And the<br />

dead sparrow says to your fingertips, your tongue and your mouth,<br />

and then mother on the back porch shouting the No! The No stella!<br />

And you are no longer stella, and the dead sparrow falls to the green<br />

grass, its words still feathery and wet on your thick tongue. The No!<br />

in the air and the orange cat on the red fence, its orange tail twisting.<br />

And you think the No! at the cat, and with your mouth you say With<br />

your mouth you say The cat’s orange tail twisting. And the dead<br />

sparrow on the green grass.<br />

Breakfast time and you are stella again, every morning<br />

surrounded by the world that is not stella. House, sun, moon, table,<br />

cocoa puffs, liquefying margarine, sprays of black bitter crumbs,<br />

mother, marcie, tablecloth and dad. The grandma on the stuffed<br />

chair, with her food tray and cracked plates. And mother holds the<br />

big spoon. The grandma says Aaaah. Aaaah, with gerber peaches on<br />

her chin, and mother says Here you go, alice. Be a good girl, and dad<br />

says There she goes. Now she’s started. Dad doesn’t like breakfast<br />

and sits on the sofa, wearing his blue robe with the torn blue pockets.<br />

And says I thought I detected a minute there. I thought I detected an<br />

actual minute of peace and quiet in this goddamn house, and the<br />

grandma says Aaaah. Aaaah. So mother gets the medicine and you<br />

drink your juice. Orange juice in mother’s glass. And the marcie<br />

clacks her new pink shoes together, requiring more toast. The marcie<br />

wears red paint on her face today, just like mother, and the voice on<br />

the radio says Better. Brighter. More Beautiful. The noise of the<br />

6

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

world on your face. You can touch it with your sticky hands.The<br />

noise of the world that is not you, and then you say And then you say<br />

Dad says Great. Now they’re both started. It’s like a choraleone<br />

vast great vegetable symphony, and takes his coors out to the<br />

sunny back porch.<br />

The grandma’s tiny eyes are red and wet, filled with words<br />

and memories of words. She says Aaaah. Aaaah, her big veiny<br />

tongue extruding from her thin lipless mouth. Her mouth red and<br />

glistening, but not like the marcie’s mouth, not like mother’s.<br />

The gerber peaches are all gone, and now the grandma loves<br />

you even more. You and your soggy toast.<br />

And so you give her some.<br />

Every weekday morning mother takes you to the special<br />

school for special children. We just hope and hope, mother says. We<br />

just hope for the lord’s compassion and his love. You hold the seat<br />

belt’s bright silver buckle in your hands. The silver buckle is a big<br />

hard word, and pulls the belt very tight. Mother says the lord words<br />

again and again, and you put your hands together to speak the lord<br />

words too, feeling them between your fingers. Then you get out of<br />

the car at your school filled with special children. Big yellow<br />

bumblebees on a big wooden sign, smooth and you like to touch.<br />

This is your bright smile, this is your round stomach. Tea, tie, toe,<br />

tum, tah, tea mrs. evans says. Her bright red fingertips touch your<br />

teeth, your tongue, putting the words there. Tih. Tih. With the tip of<br />

your teeth, with the tip of your tongue. So you tell her the grandma<br />

word and she gives you a green m&m. And she says now with the<br />

tih sound. Taaah. Taaah. Tooth, tongue, tea, toad, tot, and shows you<br />

big pictures in her lap. A big green toad, a cup of hot tea. And you<br />

say the grandma word again, and mrs. evans has more m&ms. Red,<br />

yellow, black, orange, blue, brown. Because the grandma is a<br />

tongue, a tooth, a toad. And all the other special children make<br />

grandma sounds too in their big bicycle chairs with their broken eyes<br />

and big shiny foreheads, and you’re all tea tie toe tum tah tea, and<br />

scrub the stiff colored paper with bright crayons. The crayons snap<br />

when you break them, just like mouths. You play in the tanbark yard,<br />

bang blocks to music, eat graham crackers, and dad picks you up in<br />

7

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

his car with a coors in his lap. Who’s my little dollface, he says.<br />

Who’s my little cracked brain, my little wordless wonder. Kissing<br />

you with his rough face, taking you home to drink more coors on the<br />

slanting-sunny back porch. This is your yard. This is your bright sun.<br />

This is your green, green grass.<br />

Dad built the underground shelter in the yard because he<br />

loves you. In wars words fall and explode. In wars everybody falls<br />

wordless to the ground, wordless just like you. Usually wars are on<br />

television, but when they become real, dads dig holes in the ground.<br />

Big machines come into your yard and eat it. Strange men with hairy<br />

arms and beautiful tattoos. But then the war doesn’t come and only<br />

you are stella, only you and the wordless people on TV. You like to<br />

stand on the hard wooden lid. You like to point at the big steel pipe<br />

filled with spiderwebs and shrouded, mummified bugs. The hard<br />

wooden lid fastened with a big rusty padlock. And then you ask dad<br />

And then you ask him And dad says I built the goddamn thing so<br />

when the thermonuclear war comes and blows us all to hell and back<br />

we’ll have a warm place to go to the bathroom. Now give dad a kiss<br />

and leave him alone. And dad’s rough face says kiss. Kiss kiss, it<br />

says. How’d I know they’d fucking lay me off? How’d I know I’d<br />

blow all our savings on that goddamn water trap and the bastards<br />

would lay me off? And pulls his blue robe tighter and cinches his<br />

blue flannel belt, just like the seat belt in his rattling car. The same<br />

car they drove the grandma home in when the grandma lived in a<br />

hospital with the world’s other grandmas.<br />

The marcie has her own bed but at bedtime she lies on your<br />

bed to play. The marcie plays like mrs. evans and points, reading you<br />

the big red book and says This is the spider, the stone, the snake, the<br />

sock. And her finger says Point point point. Tomcat, teddy bear,<br />

toilet, towel, tripod, toad, and you are watching the goldfish in the<br />

round fishbowl. The goldfish mouth moves too, just like the marcie<br />

mouth, and you reach for it. The goldfish says The goldfish says And<br />

you say too<br />

And the marcie says the No! and grabs your hand. This is a<br />

tripod, this is a toad. Now which is the tripod? Which is the toad?<br />

8

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

And you make your finger say Point point point, and the marcie<br />

takes your finger from her mouth and says the No! You want to touch<br />

the marcie mouth, the hard round words. You want to take the words<br />

in your hand and put them in your pocket with the masticated plastic<br />

soldier, the stray pink barbie slipper, the broken crayon. But the<br />

marcie says the No! No stella! You’re a bad girl and nobody likes<br />

you. Now go to bed now! Now go to bed now!<br />

At night the grandma sleeps in the blue room, strapped to the<br />

crooked bed with the car straps, her eyes wide open sometimes.<br />

They are very hard clear eyes, eyes eyes, and the moonlight through<br />

the curtains talks in her room, but the grandma says nothing. And<br />

you say nothing back, wearing your soft pink pajamas. The marcie<br />

asleep in your bedroom, mother and dad asleep in theirs. You touch<br />

the grandma and she opens her big black mouth. Her thin hand<br />

touches you, grabbing. And you listen to the words in the grandma’s<br />

head, like the words underground in dad’s shelter. Spiders and<br />

glistening webs across the grandma’s window, tiny bugs blurring<br />

and buzzing. The grandma sees the bugs too, the moon and the night<br />

and you. And the grandma’s veiny hand grabs your pajama top tight<br />

and you can’t get away. And then you whisper And then you whisper<br />

And when the grandma’s eyes close again, you return to your bed<br />

and dream of dad’s shelter underground, where words echo and<br />

resound, hop and crawl. If only you could reach them.<br />

Some days you don’t go to school and mother takes you to<br />

the doctor and his gleaming silver tools on a clean white cloth. And<br />

you say the grandma words and the doctor puts a mirror in your<br />

mouth. And mother says She tried to point yesterday. She pointed at<br />

the yard and tried to say something. An ess word I’m certain. When<br />

einstein was five he couldn’t even tie his shoes, and little stella can<br />

tie her shoes. Mother shows you your shoelace and pulls, and so you<br />

fix it. And the doctor says Cognitive development, aphasia,<br />

phonetic, lexical and syntactic, langue and parole. And then mother<br />

takes you home to the yard where dad sleeps on the unsprung porch<br />

sofa, and then she goes away again.<br />

9

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

Underground in the shelter the moonlight’s waiting and you<br />

walk across the hollow yard and through the hot sun. If you carry the<br />

old wood chair you can stand and peer into the rusty metal pipe. You<br />

can smell the buried life, rich with words and water and rust. You<br />

reach into the pipe with your hand and pull out ropes of dust,<br />

collapsed spiders and glistening white insect eggs. Those are the<br />

words down there, you can hear them in the pipe. Stone sea sand<br />

sister snake sun song soon. And one spider blossoms in your hand<br />

and starts to tickle. You hold it in your hand and it scrambles around,<br />

this thin tickling word. Sssssss. Sssssss. Some words go up and<br />

down, other words go back and forth. The spider is a word. The surf<br />

the sand the sea. And you push it through the pipe into grandma’s<br />

world, where grandma waits in the dark. Spider. Spider spider.<br />

That’s what you and grandma say together, underground where<br />

everything is wet and thick and real. Spider. And then you hear a<br />

round word, and under the roses you see it. It is big and fat and green.<br />

Ur, it says. Ur. It’s wet in your hands when you lift it to the steel pipe.<br />

Toad, it says. Toad. A big green toad, a cup of hot tea. Ur. Ur. Falling<br />

down the long steel pipe where the other grandma waits for it.<br />

Sometimes the grandma cries at night when you visit,<br />

strapped in her small bed, dreaming of the hard wordless night and<br />

all the world that is not stella. The grandma dreams with her mouth<br />

open, her mouth black and hollow like the steel pipe, her cheeks wet<br />

when you kiss them. Like the shelter, the grandma is filled with the<br />

world that is not grandma. Words like crumbling concrete blocks<br />

and broken red bricks, weeds sprouting and the unsprung sofa and<br />

the shelter’s hard wooden lid. The grandma has an inside, too, and<br />

you touch the tip of the grandma’s teeth, the tip of her tongue, and<br />

the grandma says Aaaah---the everything word. Aaaah. The<br />

moonlight burying itself tonight in the shelter, spilling down the<br />

thick steel pipe with the swift-gliding bugs. You reach into the<br />

grandma’s mouth looking for words there, their hard glittering<br />

edges, like plastic toys lost in the overgrown yard. In the<br />

underground shelter, swamps and sculpted faces, pockets of<br />

fossilized bones and fuel, stones etched with prehistoric brains and<br />

skulls. Aaaah, the grandma says, her hands grabbing at you. Aaaah.<br />

10

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

This is the secret here, she says. The secret sound of words, the<br />

secret dream of everything that is not stella. You love the word<br />

already as you pull it from the grandma’s mouth, the grandma’s eyes<br />

round and wide and glassy with something which is not moonlight.<br />

This is hard. This is real. You place the word on the tip of your<br />

tongue, salty on your fingertips. Your throat hurts the word,<br />

growling like a dog. “Tor, taw, ter,” you say. And the moonlight<br />

pulsing in the shelter, and the toad hopping in the dark. “Tord, tawd,<br />

toad,” you say, and that’s it there. That’s the word in your mouth<br />

now. “Toad.” Its salty taste, its scaly skin. “Toad.” And the grandma<br />

doesn’t say anything, just looking at you. Very tired now, very<br />

sleepy. “Toad toad toad,” you say. And the grandma says Aaaah very<br />

softly, very tired. Goes to sleep and her mouth falls open. Then you<br />

hear the other word there. Sssss. Sssss. Sea sand spider. Spider.<br />

Spider.<br />

You say “Toad” at breakfast and mother gives you french<br />

toast with syrup, and you eat the syrup with your tiny spoon, and jam<br />

with your toast. “Toad toad toad,” and the grandma in her chair with<br />

her soggy food, dreaming of other words beneath the yard. “Toad<br />

toad, toad toad toad.” And mother gives you a big hug, and the<br />

marcie gives you a hate face. But dad says It’s original sin. My pure<br />

little brain case has fallen into the world of already fallen language.<br />

Great. More talk, more words. Everybody in the world will be<br />

talking someday. Today I think I’ll look for a job. I gotta get out of<br />

this fucking house.<br />

And mrs. evans says Cognitive aphasia, positive<br />

reinforcement, syntactic redevelopment, and makes mother watch as<br />

she feeds you more m&ms. “Toad toad toad.” And mother says I’m<br />

so grateful to the lord, and you open the big picture book and Point<br />

point point and everything is “Toad toad toad.” And then the other<br />

thing in the shelter, the other thing tickling in the grandma’s mouth.<br />

“Spire,” you say. “Spiner. Spider. Toad toad toad.” And everybody<br />

in the entire world loves you, just like mother.<br />

There’s no big rush, little cracked brain, dad says, you in his<br />

lap and the television on. There’s no real hurry. That’s all you’re<br />

11

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

hurrying toward. That’s all language is about. And the television<br />

says hostages in lebanon, preschool drug addiction, dioxides, acid<br />

rain and nuclear waste.<br />

“Fish,” you say. “Fish fish fish. Goldfish. Goldfish daddy.”<br />

You can still feel the wet squirming word in your hand. You can still<br />

see it falling down the long black pipe. And the marcie saying you’re<br />

in trouble now, boy. You’re in trouble now. The round bowl-water<br />

empty and opaque with tiny white feces. And next day mother says<br />

Where’s our family photographs? They were right there on the<br />

mantelpiece. And the marcie puts her fists firmly on her hips to tell<br />

them, but then you say “Mother. Daddy. Marcie. Grandma.<br />

Grandma.” All those words you found in the grandma’s mouth last<br />

night. And nobody hears the marcie say a thing. Now it’s the<br />

marcie’s words that don’t really matter.<br />

“Kodak,” you tell them finally, just to let them know you<br />

understand even big words, too. “Kodacolor. Kodachrome.”<br />

But the grandma is never happy when you visit, looking at<br />

you with her big black mouth open. Aaaah. All the world’s loud<br />

words resounding and spinning down there in the grandma’s mouth.<br />

You try to pet and soothe her. These are the words, you think. These<br />

are words right here, and the grandma kicks and grabs, gurgling<br />

where your hand is, and so you take your hand back. Grandma<br />

grandma. All the darkness inside the grandma grows and grows,<br />

whispers and whispers, moves and pushes. Everything’s better down<br />

there. Down there the grandma can be happy again. Down there the<br />

grandma can be grandma again.<br />

You lead her down the hall steps. Doo, doo, doo, doo. One<br />

two two four two one two two. The grandma holds the banister<br />

because she’s afraid. She makes different noises now, wordless<br />

noises down in her stomach and thighs and feet. Doo doo doo doo<br />

doo. All the shadows hanging from the walls and furniture and<br />

curtains, and opening the squeaky picture window, the grandma<br />

leaning against you, her body thin and frail and very soft like a giant<br />

stuffed giraffe. The grandma all hollow spongy bone. The grandma<br />

all sound and word and dream. Outside, the night is filled with stars<br />

and the big fat leaning moon, humming there, filling the steel pipe<br />

12

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

and underground shelter and grandma’s black mouth. Aaaah. Aaaah.<br />

It is cold, the grandma wants to say. It is hot. It is cold and hot, big<br />

and small, boy and girl, happy and sad. Aaaah. Aaaah. Everything,<br />

the grandma says. Everything, everywhere.<br />

The grandma doesn’t like the steel pipe, the buried shelter,<br />

the heavy moonlight down there just waiting for her. You try to help<br />

her into the steel pipe. Down there, the other grandma reaches too.<br />

Down there the other grandma pulls. But this grandma says Aaaah.<br />

Scared but she wants to know. Always the deep earth, always the<br />

black night. The grandma is like the orange cat, which clawed and<br />

ran away. Grandma grandma. You try to make the soothing sounds<br />

mom makes for breakfast. There there Alice. Be a good girl. You like<br />

your cereal don’t you alice. Aaaah. Aaaah. Into the steel pipe, but<br />

both of grandma’s arms don’t fit. Pull her down, the other grandma<br />

says. Pull her down to me. And grandma’s big black mouth wide,<br />

wide with all the words she’ll find down there. Everything words.<br />

Aaaah. Aaaah. And the moon all around, and the words down there<br />

waiting with the other grandma. Louder and louder the grandma<br />

gets. Louder and louder like the moon. Aaaah. And now you try to<br />

help her. Help her head into the big steel pipe, but her head doesn’t<br />

fit. Louder and louder, deeper and deeper, worlds and words. And<br />

lights going on in all the backyards, and lights going on in your<br />

house, too. Light, light. And the grandma crying for the other<br />

grandma, for all the words she can’t quite reach when the men come<br />

with big steel tools and cut the pipe away, and then pull grandma<br />

from it.<br />

Down there. Down there. Toads hop, snakes slither, spiders<br />

scramble and crawl. Moonlight talks and dark earth listens. Pih, pih.<br />

Paper, pin, pickle, paste, plate, pastry, pigeon, plant. Person. Person.<br />

And now the r words. Rih. Rih. Everything down there in the dark<br />

and the water. And grandma embracing everything too. Vast sunken<br />

cities, countries, landscapes and stars. Hissing rivers and steaming<br />

forests. Worlds down there, worlds and words. Rih, rih. Rock, robin,<br />

rouge, rasp, rattle. Dad’s graduation ring. The marcie’s transistor<br />

radio. And grandma, grandma coming closer. The grandma’s arms<br />

13

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

big and strong and beautiful now, reaching to hold you, reaching to<br />

take you home...<br />

You wake up.<br />

You sit up in bed. Everything is black.<br />

The marcie kicks in her bed, snorts and rolls over.<br />

Outside moon talks and deep earth listens. Down there.<br />

Down there.<br />

In the grandma’s room across the hall, the grandma’s bed is<br />

empty.<br />

Grandma down there.<br />

Grandma caught a cold, mother says at breakfast. Grandma<br />

caught a cold and went away.<br />

Then after breakfast you all get in the car together and drive<br />

to the cemetery. Round brown slopes and green hedges and tidy,<br />

solid tombstones and flowers in little vases. This is grandma’s new<br />

home, this big green yard. You all stand together under the low cloth<br />

awning and watch them lower the grandma into her new, dark room.<br />

“A bad cold,” you say, and mother squeezes your hand.<br />

“Grandma has a bad cold.” And everybody back into dad’s car.<br />

Mother snuffles into her handkerchief, and the marcie reads<br />

a Doctor Strange comic book. The King-size Summer Annual.<br />

“Grandma goes away,” you say. And so you all drive home,<br />

where the other grandma waits in the darkness.<br />

Maybe she’s found what we all hope to find someday, dad<br />

says, and now you are all driving into the driveway of your big warm<br />

house. The dark clouds breaking apart. Bright blue sky blazing<br />

through. And you want to tell dad the secret as he lifts you under one<br />

arm and carries you to the front door. Come on, my little sack of<br />

potatoes, dad says. Come on, my little fat bag of laundry.<br />

Dad is bigger, but you know the secret.<br />

“Everything,” you whisper. “Everything, Daddy.”<br />

14

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

Man Walking at 24 Frames Per Second<br />

from The Adventures of Lucky Pierre<br />

Robert Coover<br />

As he enters the jostle, getting dragged down the street<br />

through the snow and civil litter, the illusion of freedom fades and<br />

an enfeebling depression creeps over him like a slow lap dissolve,<br />

loosening his limbs and probing his sinuses like the onset of a new<br />

cold. News photos stare at him from wastebins and the corners of<br />

park benches, but he cannot bring himself to animate them. His feet<br />

crush something or other about once every eighteen frames, but he<br />

doesn't want to know what-what do I care about causes, he insists.<br />

He looks up. Just the usual snow, clouds hanging heavy like the dugs<br />

of a wet nurse, the odd suicide, nothing new. What then? He feels<br />

like he’s lost something, something infinite and irrecoverable. Ah<br />

well. Time probably, that's all, the old rue. He's always losing it,<br />

always in grief about it. Laymen pass, hardly even counting, content<br />

with shouldering one another off the frozen sidewalks and singing<br />

their timeworn mating hymns. He envies them, chins tucked in their<br />

collars, living in lyric time, suffering only on the odd birthday when<br />

they fail to forget. He probably lived like that once himself. Not any<br />

more. Ever since they hit him with the news that time was something<br />

that got shot past at twentyfour frames per second, he's been in an<br />

absolute panic about it.<br />

Well, at least he knows who he is, why he suffers-he should<br />

be carrying his jewels of office out in the open, but he feels<br />

vulnerable in this spectral flux, and faintly irreverent. No, no, he<br />

does not know who he is, who does he think he's kidding? Maybe in<br />

fact that's just what he's been losing. Laying waste his identity at 24<br />

fps. Maybe it's Cassie's fault, maybe she's messing him up. He<br />

remembers sitting at an editing bench with her one afternoon,<br />

looking at a reelfull of spliced-together goof-ups from the<br />

cuttingroom floor: the tagends of orgasms, flash frames, miscues,<br />

foggy runouts and blistered closeups, jittery tracking shots, clumsy<br />

wipes-all of it joined together just as she's picked it up: forwards,<br />

backwards, emulsion in or out, grease-penciled, notched, or<br />

15

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

punched. Cassie is perversely fascinated with all the peripheral gear<br />

of film, things like black leader, glue, magic markers, static, shims<br />

and sun guns, perforations, ident trailers, edge numbers. Sitting<br />

there, he's watched himself on the editing machine fall out of bed<br />

and out of focus, go limp in a stockyard, sneeze in the middle of a<br />

gamahuche, withdraw wearily from the ass of a cleaninglady, the<br />

lips of a chambermaid, and the quim of a queen, all decorated with<br />

water spots and cinch marks, get hung up in a child-star and<br />

overexposed in the subway, scalded in the shower and stuck in the<br />

revolving doors of an office building.<br />

-Ouch. You're depressing the hell out of me, Cassie.<br />

She winds onto a medium shot of him walking through the<br />

crowds of a city street in a snowstorm. She locates a moment when<br />

he steps off a curb, plays it back and forth, back and forth, sometimes<br />

slowly, sometimes more quickly, just that brief movement, stepping<br />

down, glancing at the traffic, his weight shifting, prick dipping then<br />

bobbing up again.<br />

-Why are you showing me that, Cassie? I feel like a goddamn<br />

ass!<br />

She zooms in on his eye, catches just the downward tilt of the<br />

head, the left-to-right roll of the eye, the dim background blur of part<br />

of a sign on a passing bus, a block letter “D” in soft focus, sliding<br />

back and forth past his head, as his head drops slightly in the frame,<br />

his eye moving left, right, left again, then back up, over and over,<br />

that “D”, blurring by, his head... he becomes completely absorbed,<br />

forgets it's himself, just that simple pure motion, nothing, yet a<br />

thousand things to see there, and all of it locked into an elemental<br />

and irreducible whole.<br />

-All right, it's beautiful, Cassie. But it's only six frames. Onefourth<br />

of a second. Put that on the screen and pfft! it's over before<br />

you've seen it.<br />

She doesn’t reply.<br />

-Is that why you've never made films, Cassie?<br />

She starts cranking on the rewind. He thinks at first that she's<br />

hurrying ahead to some other scene, but she just keeps winding the<br />

film up faster and faster. He can't see anything, just a meaningless<br />

blur, and he wonders if maybe she's freaking on him. Then, slowly,<br />

16

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

an image begins to take shape in the hiss and rattle of passing<br />

footage: it is he, Lucky Pierre, in slow motion, dreamily afloat in a<br />

cosmic whirlwind of past faults, getting it up... and up... and up...<br />

spraying semen like seeds... like stars! He becomes hypnotized by it,<br />

fantastic, doesn't even feel the cold, watches waves of females<br />

floating by like schools of fish to absorb the fall of cum, writhing on<br />

meadows where it showers down like dew... then slowly it begins to<br />

wind down, the image fades, there's just the noisy blur, the parade of<br />

fuck-ups, and he's back on the streets again, cold, hungry, lost,<br />

tainted with cinch marks and water spots, slowing down, down,<br />

unable to go on, ducking into an open doorway to get out of the wind<br />

and save his life.<br />

17

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

The Titles Sequence<br />

from The Adventures of Lucky Pierre<br />

Robert Coover<br />

(Cantus.) In the darkness, softly. A whisper becoming a<br />

tone, the echo of a tone. Doleful, a soft incipient lament blowing in<br />

the night like a wind, like the echo of a wind, a plainsong wafting<br />

distantly through the windy chambers of the night, wafting<br />

unisonously through the spaced chambers of the bitter night, alas,<br />

the solitary city, she that was full of people, thus a distant and hollow<br />

epiodion laced with sibilants bewailing the solitary city.<br />

And now, the flickering of a light, a pallor emerging from the<br />

darkness as though lit by a candle, a candle guttering in the cold<br />

wind, a forgotten candle, hid and found again, casting its doubtful<br />

luster on this faint white plane, now visible, now lost again in the<br />

tenebrous absences behind the eye.<br />

And still the hushing plaint, undeterred by light, plying its<br />

fricatives like a persistent woeful wind, the echo of woe, affanato,<br />

piangevole, a piangevole wind rising in the fluttering night through<br />

its perfect primes, lamenting the beautiful princess become an<br />

unclean widow, an emergence from C, a titular C, tentative and<br />

parenthetical, the widow then, weeping sore in the night, the candle<br />

searching the pale expanse for form, for the suggestion of form, a<br />

balm for the anxious eye, weeping she weepeth.<br />

The glimmering light, the light of the world, now firmer at<br />

the center, flickers unsteadily at the outer edges, implications of<br />

tangible paraboloids amid the soft anguish, the plainsong exploring<br />

its mode, third position athwart, for among all her lovers there are<br />

none to comfort her, and the eye finding a horizon, discovering at<br />

last a distant geography of synclinal nodes, barren, windblown, now<br />

blurring, now defined.<br />

Now defined: a strange valley, brighter at its median and<br />

upon the crests than down the slopes, the hint there perhaps of<br />

vegetation, like a grove of pines buried in the snow, and still the<br />

chant, epicedial, sospirante, she is driven like a hunted animal, C to<br />

C and F again, she findeth no rest. How many have died here?<br />

18

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

The plainchant, blowing through the gloomy valley like an<br />

afflicted widow, continues to mourn the solitary city. Overtaken<br />

amidst the narrow defiles. Continues to grieve, ignoring the gradual<br />

illuminations, a grief caught in secret acrostics, gone into captivity.<br />

All her gates are desolate. The eye courses the valley to its yawning<br />

embouchure, past a scattering of obscure excrescences with bright<br />

tips, courses the dark defile to its radical, this pinched and<br />

woebegone pit, mourning its uprooted yew, her priests sigh, her<br />

virgins are afflicted. Gravis. Innig. In bitterness, yes con amarezza,<br />

she is with bitterness.<br />

Beyond this gnurled foramen, crumpled crater too afflicted<br />

to expose its core to chant or candle, lies a quieter brighter field, yet<br />

one ringed about with indices of a multitude of transgressions, tight<br />

with uncertainty and attenuation, and, as it were, mere propylaeum<br />

to the ruptured conventicle of extravagance and savagery just<br />

beyond, just below...<br />

Ah! what a sight, this wild terrain cleft violently end to end<br />

and exposed like an open grave! The light flares and wanes, flutters,<br />

as though caught in a sudden gale, as though eclipsed by a flight of<br />

harts. 0 woe, her princes are denied a pasture, nature is convulsed,<br />

and a terrible commotion, sundered by plosives, sounds all about.<br />

Angoscioso and disperato, rising and falling intervals in the<br />

tremulous matinal gloom.<br />

Black bars radiate from this turbulent arena, laid on the<br />

surrounding hills like the stripes of a rod in the day of wrath, and at<br />

the end of the black bars, like whipstocks for the maimed: letters.<br />

Flickering neumes. VAGINAL ORIFICE. LABIA MAJORA. And<br />

not a propylaeum: a PERINEUM. ANUS. Alas, despised because<br />

they have seen her nakedness. C to C and F again. Like the echo of<br />

letters, the shadow of codes, the breath of labia, yea, she sigheth, and<br />

turneth backward, a simple canticle, notations writ on the ass end of<br />

a kneeling woman, this kneeling woman, this ass end: URETHRA,<br />

CLITORIS, black indications quavering in this ghostly light, the<br />

light of the world, the light of a solitary city at the end of night, the<br />

coldest hour. Crying: her filthiness is in her skirts.<br />

Between the spreading intrados of the massive thighs, below<br />

the keystone cunt, all barbed and petaled, through a filigree of letters<br />

19

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

suspended mysteriously in the archway-FLESHY PILLOW, now<br />

sharp, now diffuse-beyond and through all this, we see the distant<br />

teats, hanging in the wind, blowing in the dawn wind, oh, therefore<br />

she came down wonderfully, her last end forgotten, heavy teats<br />

ready for milking, their fat nipples swollen with promise. They sway<br />

in the wind, and something is indeed falling from them, yes, like<br />

frozen milk: snow! snow is falling, falling from the big teats, snow<br />

is swirling in the bitter wind, under the pale corrugated belly of the<br />

wintry dawn, blowing out of the ANUS and the VAGINAL<br />

CANAL, it is snowing on the city.<br />

0 Lord, behold my affliction! A vast desolation, the city, the<br />

afflicted city, far as the eye can see, stones heaped up to the end of<br />

the earth, lying dead in the winter, dead in the storm, whose hands<br />

could have raised up so much emptiness? the enemy hath magnified<br />

himself. Yet decrescendo this, spreading his hand on her pleasant<br />

things, diminuendo, the intervals blurred now by the grinding whine<br />

of low-geared motors, for in spite of everything dim towers, rubytipped,<br />

rise obstinately through the blowing snow, a multitude of<br />

lamps blink red and green in fugal progressions down below,<br />

chimneys puff out black inversions and raise a defiant clamor of<br />

colliding steel, and the snow itself is swallowed up by a million dark<br />

alleys, just as their fearful obscurities are obliterated by the blinding<br />

snow.<br />

Through the city, through the snow, under the gray belly of<br />

metropolitan morning, walks a man, walks the shadow of a solitary<br />

man, like the figure in pedestrian-crossing signs, a photogram of a<br />

walking man, caught in an empty white triangle, a three-sided<br />

barrenness, walking alone in a life-like parable of empty triads,<br />

between a pair of dotted lines, defined as it were by his own purpose:<br />

forever to walk between these lines, snow or no snow, taking his<br />

risks-or rather, perhaps that is a pedestrian-crossing sign, blurred by<br />

the blowing snow, and yes, the man is just this moment passing<br />

under it, trammeling the imaginary channel, the dotted straight and<br />

narrow, at right angles. There he is, huddled miserably against the<br />

snow and wind and the early hour, shrinking miserably into his own<br />

wraps, meeting the pedestrians, those shadows of men making their<br />

dotted crossings, at right angles, meeting some head on as well,<br />

20

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

brushing through the cold and restless crowds, as horns sound and<br />

airbrakes wheeze, sirens wail, all her people sigh, they seek bread,<br />

the last whimpering echo of a plainsong guttering like a candle in the<br />

morning traffic.<br />

His hat jammed down upon his ears and scowling brows, his<br />

overcoat lapels turned up to the hatbrim, scarf around his chin, he is<br />

all but buried in his winter habit. Only his eyes stare forth, aglitter<br />

with vexation and the resolution to press on, and below them, his<br />

nose, pinched and flared with indignation, his pink cheeks puffed<br />

out, blowing frosty clouds of breath through chattering teeth. His<br />

mouth, under his moustache, is drawn into a rigid pucker around his<br />

two front teeth, my god, it is cold, what am I doing out here? His<br />

hands are stuffed deep in his overcoat pockets, and poking forth<br />

from his thick herringbone wraps like a testy one-eyed malcontent:<br />

his penis, ramrod stiff in the morning wind, glistening with ice<br />

crystals, livid at the tip, batting aggressively against the sullen<br />

crowds, this swirling mass of dark bodies too cold for identities,<br />

struggling through the snow, their senses harrowed, intent solely on<br />

keeping their brains from freezing.<br />

Oh, my poor doomed ass, I’m in real trouble, he whimpers to<br />

himself as he trundles along, tears running down his cheeks, teeth<br />

clattering, frozen snot in his moustache, up against it, expletives the<br />

only thing that can keep him warm, that he can pretend will keep him<br />

warm, shouldering his way through a thickening stupefaction,<br />

sidestepping the suicides, those are the lucky ones, man, not you,<br />

who gives a shit, all running down anyway, why do you have to play<br />

the fucking hero?<br />

He walks through winter like that, wheezing and whistling,<br />

feeling sorry for himself, aching with cold, sick of keeping it up<br />

anymore, but scared to die, picking them up, putting them down, hup<br />

two three, attaboy, yes, there he goes, a living legend, who knows,<br />

maybe the last of his kind, seen through a whirl of blowing snow,<br />

through a scrim of messages, an unfocused word-filter, lamenting<br />

the world’s glacial entropy and the snow down his neck, bobbing<br />

along in this cold sea of pathetic mourners, this isocephalic<br />

compaction of misery and affliction, the dying city and he in it,<br />

whimpering: piss on it! yet refusing to quit, refusing to tip over and<br />

21

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

get trampled into the slush, and so celebrating consciousness after<br />

all, in his own wretched way, the man of the hour, the one and only:<br />

Lucky Pierre.<br />

The swish and blast of the passing traffic modulate into a<br />

kind of measureless rhythm, not a pulsation so much as an aimless<br />

rising and falling, sometimes blunted, sometimes drawn brassily<br />

forth. Subways rumble underfoot, airdrills rattle in alleys, and<br />

there’s the thunder of jets overhead like occasional celestial farts.<br />

Tipped wastebaskets spill bottles, newspapers, pamphlets, dead<br />

fetuses, old shoes. Cars, spinning gracefully in the icy streets, smash<br />

decorously into each other, effecting dampened cymbals, sending<br />

heads and carcasses flying through their shattering windshields and<br />

crumpling into snowbanks. Above the crowds, a billboard asks:<br />

WHAT IS MY PRICK DOING IN YOUR CUNT, LIZZIE? Six<br />

blocks away and around the corner, a theater marquee replies:<br />

FUCKING ME! FUCKING ME! O SO NICELY! Smoke rises from<br />

a bombed-out building, and a crowd has gathered, warming<br />

themselves by the ruins. Distant crackle: trouble in the city.<br />

Somewhere.<br />

A little old lady, leaning on a cane, hesitates at a curb, peers<br />

up at the light, now changing from green to red. Her spectacles are<br />

frosted over, icycles hang from her nose, her free hand trembles at<br />

her breast, clutching an old frayed shawl. The man, trying to catch<br />

the light, comes charging up, but not in time, skids to a stop,<br />

glissandos right into the old lady’s humped-over backside, bowling<br />

her head over heels into the street with a jab of his stiff penis. There<br />

is a brief plaint like the squawk of a turkey as a refuse truck runs her<br />

down. Old as she was, it’s still all a little visceral, but soon enough<br />

the traffic rolling by has flattened her out, her vitals blending into the<br />

dirty slush, her old rags soaking up the rest.<br />

-Pity, someone mutters.<br />

-Life’s tough.<br />

-Where’s the street department? Goddamn it, they’re never<br />

around when you need them.<br />

The light changes, the old lady is trampled away. There’s the<br />

blur of hurrying feet, kicking, splattering, through the blood, slush,<br />

and snow. Thousands of feet. Going all directions. Whush, crump,<br />

<strong>22</strong>

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

crump, stomp. Crushing butts, condoms, fishheads, gumwrappers.<br />

Someone’s pocketwatch. Beer cans. Crump, crump, crump, a kind of<br />

rasper continuo. Windup toys and belt buckles. Bicycle sprocket.<br />

Ticket stubs. All those frozen feet, shuffling along, whush, whush,<br />

almost whispering: That’s right, Maggie, lift your arse and whush,<br />

crump, crump, tickle my balls! Oh christ, it’s cold! It’s too fucking<br />

cold!<br />

Listen, get your mind off it. Think of something else. E.g.<br />

comma green places. Where it’s warm exclamation mark. That’s it.<br />

Chasing about in a meadow at the edge of a forest, how about that?<br />

Come on, give it a try, make it yet, hup two three, she runs behind a<br />

tree, peeks out, showing her ass. He bounds over fallen trunks,<br />

crackling branches and dry leaves. Splashing through a brook. Up<br />

mossy rocks. Delicious stink. Yeah, good, moving along now, keep<br />

it up colon. Cavorting in soft grass. Some kind of music...<br />

(Front end of a heavy bus, barreling through the city street,<br />

spitting up snow, whipping it into black slush: BLAAAAT!)<br />

Cantilena maybe, piped on a syrinx, that’s good, Cissy’d like<br />

that, all’ antico, right. Her handsome ass aglow in the sun. He licks<br />

it, tongues her cunt. Yum. She kicks him, springs away. They circle<br />

each other. Hah! She scampers off, he chases, catches her, they roll<br />

about, flutes fading, rest. Mmm. Silent now in the sunny green<br />

meadow, a sweet heady peace, street sounds diminishing to nothing<br />

more than a playful wind in the fading forest. Yes, good. He pokes<br />

his nose in her cunt again, nuzzles dreamily about.<br />

(Sudden roar of the bus, splattering through snow, blackened<br />

with soot, its windows greasy, foglights glowing dully. City streets,<br />

buildings, people, traffic, go whipping by)<br />

Sshh! Getting there! Twelve girls now, a pretty anthology, in<br />

the sunny meadow, yes, twelve of them, standing on their heads,<br />

back to back, butt to butt, legs spread like the petals of a flower. He<br />

hovers, admiring the corolla, many-stemmed, each with its own<br />

style and stigma, the variegated pappi blowing in the soft summer<br />

breeze; then he drops down to nibble playfully at the keels, suck at<br />

the stamens, slip in and out of septa. Distantly: the sound of muted<br />

trumpets-<br />

23

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

BllaaaAAAAAAATTT! He jumps back to the curb, but too<br />

late, a bus bearing down on him-THWOCK!-whacks his prick as it<br />

goes roaring by: he screams with pain, spins with the impact, and is<br />

bowled into the crowd, now crossing with the light, spilling a dozen<br />

of them. He catches a glimpse of the bus gunning it on down the<br />

street, an advertisement spread across its rear: I CAN SEE HER<br />

CUNT, GUSSY! and what looks like the eye of a pig in the back<br />

window, staring at him. The crowds, rushing and tumbling over him,<br />

curse and weep:<br />

-What is it like, Nelly?<br />

He hobbles to the edge of the flow, nursing his bruised cock,<br />

looking for a reason to go on, looking for something to wrap it in. He<br />

finds a bum sleeping under a newspaper and appropriates page one.<br />

Over a photo of the Mayor at a public execution of three small<br />

children, believed to be the offspring of urban guerrillas, is the<br />

headline: A LARGE HAIRY MOUTH SUCKING HIS PURPLE<br />

PRICK.<br />

Aw hey listen: fuck it. Quit. Yeah.<br />

He sits on the curb, snuffling, huddled miserably over his<br />

battered rod, trying to coax green dreams out of his iced-up lobes,<br />

feeling the snow creep up his ass, no sorrow like my sorrow: bitter<br />

snatch of the diatonic aubade. Something seems to leave him, some<br />

spring released, a slipping away...<br />

No! he cries in sudden panic, leaping up. Forget that shit,<br />

fade it out, no more messages, pick ‘em up and put ‘em down, hup<br />

two three four, he’s running along now, prick waggling frantically,<br />

stiffarming the opposition, recocking the spring, leaping the lifeless,<br />

close now, yeah, central heating, all that, gonna make it-oof! sorry,<br />

ma’am!<br />

-Good morning, L.P.!<br />

-Good morning, love! (Whew!) After you!<br />

-Thank you, Mr. Peters!<br />

-Morning, sir! Thank you, sir!<br />

-Ah, damn it, is it nothing to you, all ye that pass by?<br />

24

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

J.<br />

Nancy Sweet<br />

The alarm went off and my arm jerked from beneath the<br />

covers to hit the button for another 20 minute’s sleep. But I was<br />

awake. I knew it. I never went back to sleep. I pulled my robe around<br />

me and headed for the kitchen to make coffee. Then into the shower.<br />

As I stood there with the hot water pouring over my head I thought<br />

I heard the doorbell buzzing, so I rinsed off in a hurry, threw a towel<br />

around me, and ran out the bathroom door only to hear my alarm<br />

going off again.<br />

I shut it off for good this time, went into the kitchen and<br />

poured a cup of coffee. I threw an ice cube in it so I could drink it<br />

right away. “Oh shit, it’s almost noon,” I said as I pulled my clothes<br />

on, “I gotta get going!” I ran out the door to J.’s house, screeched to<br />

a halt in the driveway behind her apartment building, and ran in the<br />

back door. When I pushed the elevator button and it didn’t open<br />

immediately, I decided to walk the three flights to her floor. I panted<br />

down the hallway to #306 and started banging loudly.<br />

“Wake up, J., it’s me! Come on, open up in there. We gotta<br />

get going!”<br />

More banging, and then, as I pressed my ear to the door, I<br />

could hear movement inside. She’s awake! The front door opened<br />

slowly, and there was J. looking like she always does when she first<br />

wakes up - hair all mashed to one side, a huge T-shirt slipping off one<br />

shoulder, and wearing those stupid giraffe slippers with the necks<br />

flopped over to one side so the giraffe heads lay sideways on the<br />

floor and dragged along the ground as she shuffled around in the<br />

morning.<br />

“What time is it?” she mumbled.<br />

“It’s time to get up. Time to get down to the Neighborhood.<br />

We have to get enough for tomorrow too, it’s Sunday, and no one is<br />

ever around on Sunday. How much money do you have?”<br />

With a slow sweep of her arm J. pointed to her oversized<br />

purse lying in a heap of clothes next to her bed.<br />

“I don’t know, you count it.”<br />

25

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

“Okay, you go get in the shower. Here, I brought you some<br />

coffee.”<br />

J. slumped down at the table, arms hanging loosely at her<br />

sides. Her head slowly tilted forward till her lips met the coffee cup<br />

sitting in front of her. She took a few sips, seemed a little more<br />

awake, and stumbled off toward the shower.<br />

“Hey, those giraffes have absolutely no hair on the sides of<br />

their heads where they drag on the floor. They look ridiculous.”<br />

“Oh, shut up!” she retorted, “My dad got these at Neiman<br />

Marcus for me on my 18th birthday.”<br />

“Well, for Chrissakes, J., you’re 26 years old now, it’s a<br />

wonder they still have heads!”<br />

While J. was in the shower, I popped Janis Joplin’s Greatest<br />

Hits into the tape player, picked up her purse and unzipped the big<br />

side pocket and pulled out the wads of bills. I could never quite<br />

believe that she just shoved money in her purse like that. Mine was<br />

always perfectly neat, all bills facing the same way, in order<br />

according to denomination. Here were wads and wads of bills and<br />

change just crammed in the pocket and zipped up!<br />

I laid them all out in piles, tried to unwrinkle them the best I<br />

could, and counted out the change. I looked through the rest of the<br />

purse and found a $20 dollar bill in her checkbook, and $7 in the<br />

little zipper pocket. I heard the water shut off in the shower.<br />

“How much do we have?” J. asked as she swung around the<br />

corner from the bathroom, towel wrapped around her middle and<br />

one wrapped on top of her head sticking up about a foot.<br />

“I don’t know yet. God, you’ve got money all over your<br />

purse. How do you keep track of it?” I asked.<br />

“I don’t.”<br />

“Oh, J., here’s our favorite part,” I yelled.<br />

I jumped up, threw my arm over J.’s shoulder, and we both<br />

stood there with our fake microphones in our hands singing along<br />

with Janis Joplin,<br />

Come on, come on, come on<br />

Take another little piece of my heart, now baby<br />

You know you got it<br />

If it makes you feel good<br />

26

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

Oh, yes, indeed<br />

“So do we have enough money, or what?” J. asked, reaching<br />

for her cup of coffee.<br />

“Yeah,” I said, “enough for what we need. If we want more,<br />

we can always drive down tomorrow and see if anyone is around.<br />

Get dressed, and I’ll get the stuff out so it’s ready when we get back.”<br />

I put the money into a neat pile, stuck it in my purse, and got<br />

out the little black box. I took the empty pizza box off the table,<br />

brushed away the crumbs, laid out the spoons, one on each side of<br />

the table, washed out four syringes and laid two apiece next to the<br />

spoons.<br />

“Come on, let’s go. What are you waiting for?” said J.<br />

I looked up to see her standing there fully dressed, hands on<br />

hips in mock impatience, with a wide grin on her face.<br />

“You bitch!” I yelled.<br />

We laughed as we ran out the door and down the three flights<br />

of stairs. We pushed open the back door and headed toward J.’s car.<br />

We always took her car. She had a 1977 Olds Cutlass Supreme. I had<br />

a little Fiat.<br />

“Why do you suppose I always get the tickets when we’re<br />

drag racing home?” I asked, sliding into the seat. “You’re always<br />

ahead of me going 95, and I’m screaming along behind doing 85, but<br />

I always get the damn speeding tickets. I paid $20 out three times<br />

last month - twice to the same cop!”<br />

J. seemed to think about this as we pulled out onto Sheridan<br />

Road.<br />

“You know why you get the tickets?” she asked. “No, why?”<br />

“Two reasons: First of all, the cop knows my car is faster than his -”<br />

As I burst out laughing, she said, “Now wait a minute - and<br />

the second reason is, now that the cop got $20 from you two times,<br />

he’s going to say to himself every time he sees your car -’Oops, there<br />

goes my $20 dollar bill, better go get it.’ I mean, how many gold<br />

Fiats are there going 85 miles an hour down Lake Shore Drive every<br />

night between 2:00 and 2:30 in the morning? About one, right?”<br />

“Well, you’re about half right,” I argued, but this car can’t<br />

beat no cop car.”<br />

27

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

As we pulled onto the Drive, J. floored the car. In no time we<br />

were doing 90 mph. “Hey, cool it,” I said, “It’s the middle of the day,<br />

slow down, J. Geez, when I’m doing 85 in my Fiat, it’s buzzing like<br />

hell, and it feels like I’m about two feet off the ground. This is like<br />

a fucking limousine, you don’t feel anything.”<br />

We slowed down by the time we got into Uptown. By then,<br />

the traffic was heavier. Then we swooped around the North Avenue<br />

exit curve and went west to Milwaukee Avenue.<br />

“Ah, yes, the Neighborhood,” I said. “I can smell the dope. I<br />

can see the junkies. Look, there’s Kenny. Remember the time he<br />

took my $20 and said he’d be right back?”<br />

“Shut up,” J. whispered loudly as we turned on to our side<br />

street. “Do you see anybody? Do you see Jose?”<br />

As we cruised slowly down the street, I could feel that<br />

something was not right. Suddenly we saw three cops jump out of a<br />

car parked against the curb. They ran straight for Jose who was<br />

sitting outside on the top step of his front porch. He knew enough not<br />

to move when he saw them coming. They grabbed him by his arms,<br />

drug him over to their car, and threw him face down on the hood.<br />

They kicked his feet apart, and when he tried to lift his head, they<br />

grabbed him by the hair and pushed his head down onto the hood<br />

again.<br />

We sped up a little, turned our heads straight ahead so the<br />

cops couldn’t see us gaping as we drove by, and disappeared around<br />

the corner.<br />

“Oh shit, now what do we do?” I asked.<br />

“I don’t know,” said J., “They won’t bust him, he never has<br />

any dope on him, or inside his house. They can’t do anything.”<br />

“Well, let’s get out of here. We don’t want to be sitting<br />

around the corner when the cops leave. Let’s go over to Armitage<br />

and get an Italian Ice, then go back.”<br />

As we sat on the curb chewing frozen lemon rinds our<br />

thoughts turned to ‘What if’s.’<br />

“What if they’re still there?” I chimed in first. “We’ll be sick<br />

as dogs at work tonight. What if no one is there? Then what do we<br />

do?”<br />

28

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

“Let’s go back. It’s been 45 minutes,” said J. As we pulled on<br />

to_____street again, there was Jose, sitting on his front porch just as<br />

before. He jumped down all five steps and ran to meet us.<br />

“I was wondering if you guys were coming back,” he smiled.<br />

“Here, have an Italian Ice. Are you all right?” asked J.<br />

“Bueno, but my cabesa hurts like hell,” he said. “How many<br />

do you ladies want today?” “We’ll take eight, we have $160,” I<br />

jumped in. “We might want more for tomorrow - say, where is<br />

everyone on Sundays anyway?”<br />

“Shit man, I go to church with my family, but I’ll meet you<br />

here at 2:00, okay?” said Jose.<br />

“We’ll be here, definitely,” said J.<br />

The ride home was always very fast - even considering that<br />

all speed limits were obeyed, of course. As we entered J.’s apartment<br />

door the usual inaudible sigh of relief passed over both of us. J.<br />

kicked off her shoes and put on her ridiculous slippers. I ran for the<br />

glass of water and the spoons, and soon our heads were slumped<br />

over to one side just like those stupid slippers.<br />

29

Tuna on White<br />

Matt Osing<br />

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

I’ve got a sandwich. Tuna on white, wrapped in wax paper<br />

so they’ll know it’s mine, won’t eat it for me. This sandwich is gonna<br />

get me beyond the thank-you bleat of the limited egress system,<br />

through a door, another shift, eventually a payday. It’s the reason I<br />

never bitch, why the nurses all like me, why I get stuck with all the<br />

enemas.<br />

I get to watch failed career jocks with serious doubts smirk<br />

behind my back. Me with the hot water bottle and hose closing the<br />

doors one by one, thinking about my sandwich, how the kitchen staff<br />

should knock off the commodity cheese and surplus bananas, as<br />

these foods are binding.<br />

The residents are glad to see me because I tell them it’s all<br />

garden dirt to me. I like Sheila the best. For one thing, she agrees<br />

with me on things. Like when I say how nobody really knows the<br />

backs of their hands. “Faces maybe,” she says, but Sheila agrees,<br />

most people are lost. Shelia admits she is, says she’s tired of all the<br />

other aids speaking mother-ease as if she were an infant. Sheila’s 32.<br />

I tell her how I’m sick of the smirkers calling me big-guy, thumbing<br />

me up, high fives, telling me, “Hey, Rock-n-Roll Big Guy, Rock-n-<br />

Roll.”<br />

Sheila closes her eyes as I put her in the left Simms position,<br />

on her side, her one atrophied leg bent just so. Gloved, I stimulate<br />

her bowel with my index finger, insert the nozzle and unclip the<br />

flow. Sheila smiles to herself, and I know I’m right, right about<br />

people.<br />

Sheila has developed a hemorrhoidal tag, her anus like a<br />

tightly clustered raspberry pushing out one of it’s drupelets to ripen<br />

faster. People don’t really consider the backs of their hands.<br />

Sometimes when we wipe we get shit on the base of our thumbs.<br />

I showed Sheila a trick. If you splay your fingers, and press<br />

palms and fingers with another’s hand, then stroke two of the fingers<br />

as one, one yours, one theirs, it’s exactly what it feels like to touch a<br />

dead man’s finger, in exactly that way. Sheila will try it with one of<br />

30

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

the nurses. The nurses like Sheila and will humor her. I’ll be in the<br />

breakroom in my chair by the suggestion box, having my sandwich.<br />

31

The Blue Wallet<br />

William T.Vollmann<br />

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

The thing you dislike or hate will surely come upon you, for<br />

when a man hates, he makes a vivid picture in the<br />

subconscious mind, and it objectifies.- Florence Scovel<br />

Shinn, Your Word is Your Wand (1928) *<br />

1<br />

I loved Jenny most when, sitting beside her at sentimental<br />

movies, I would look away from the big screen where the beautiful<br />

actress was about to leave her lover forever, and see Jenny sitting<br />

upright in her chair, her black button-eyes concentrating so hard on<br />

the film, while she chewed and chewed her gum so earnestly, and I<br />

ran my forefinger below her eyes to verify that her face was wet, that<br />

Jenny was crying for the people on the screen, crying in perfect<br />

placid happiness over this debacle that had never happened; and I<br />

knew that after the movie was over Jenny would forget that she had<br />

cried, but she would feel refreshed by her tears. - How harmless it all<br />

was! Sometimes I myself, reminded by the actress of my own<br />

failures, would be scalded by a single heavy tear; but this would not<br />

be a good feeling, and I would have to stroke Jenny’s wet eyelid<br />

again with my finger to be soothed.<br />

2<br />

“I got in a fight with this fucking fat woman!” cried<br />

Bootwoman Marisa, who was now a bicycle messenger. Her legs<br />

were covered with bruises like rotten apples. “Right when you get to<br />

the end of the block you go up onto the sidewalk. And there was like<br />

a Mack truck coming right at me, and it was totally obvious that I<br />

was not gonna to be able to fucking avoid it unless I put on my<br />

brakes to skid to like avoid this woman. And I told her, I go, MOVE!<br />

I yelled really loud; I go, MOVE! and she goes, No!” - and, imitating<br />

the woman’s voice, Marisa expressed this determined negation in a<br />

birdlike screech - “and she stands right there, and I go, Fine! I’m<br />

* Marina del Rey, California: DeVorss & Company, P. 74.<br />

33

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

gonna hit you! - So,” she laughed, “I hit her, straight on. - And she<br />

throws me off my bike! She fuckin’ throws me off my bike, an’ my<br />

bike is goin’ that way; I’m goin’ this way, and I just got off and<br />

punched her in the face!”<br />

“All right!” yelled everyone, with enthusiasm as blue-white<br />

and glowing as the most powerful cleansing powder. This<br />

enthusiasm could have eaten holes in walls.<br />

“Jesus! BAM!” screamed Marisa, so loudly that the dog<br />

began to bark. “And I start screamin’, ‘Bitch, what in the fuck you<br />

think you’re doing? Bitch! And she’s opening up her little purse, and<br />

I’m just waitin’ on her. Bitch! Bitch! And she goes, ‘Well, you were<br />

in the wrong! You were in the wrong!’ - and this black guy steps<br />

between us and goes, ‘Come on, don’t get in a fight,’ and I go,<br />

‘BITCH! YOU NIGGER-FUCKING WHORE!’ - and she turns<br />

around and she goes, ‘You got that shit correct,’ and I go, ‘Of<br />

course! You’re too fuckin’ fat for a white man to fuck your lousy<br />

ass!”’<br />

3<br />

Marisa never liked me as well as I liked her, partly (I<br />

suppose) because I wore glasses and did not know how to fight<br />

hand-to-hand, in the knightly fashion of skinheads and other streetconquerors,<br />

but partly also because my girlfriend was Korean. She<br />

did like me enough to be polite to Jenny, it being one of the rules that<br />

if somebody was your friend you did not fuck around with his lover,<br />

as was demonstrated when Ken’s girl Laurie went up to Dickie at a<br />

skinhead party and touched his shoulder to ask him for a cigarette,<br />

and Bootwoman Dan-L appeared from nowhere and warned Laurie<br />

to stay out of her territory unless she wanted to get beaten up. So<br />

because Jenny was in my territory Marisa tolerated her. - After all,<br />

Marisa did like me O.K. - This must have been why she sometimes<br />

came over and cooked me breakfast: huge omelettes with<br />

mushrooms and cheese and bacon and red onions, while in a<br />

subordinate frying pan her home fries sizzled obediently, becoming<br />

the golden-brown of Jenny’s skin, at precisely the moment when the<br />

cheese melted and the mushrooms were done and the steam rose<br />

from the titanic omelette like a chord from some cathedral organ,<br />

and Marisa would start doing the dishes that had piled up in the sink<br />

34

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

and say, “Boy, your girlfriend doesn’t take very good care of you,<br />

does she? What a mess this place is,” and I’d stand beside her at the<br />

sink and feel good that Marisa was being good to me; and<br />

meanwhile I’d be drinking whiskey out of the bottle because I was<br />

hungry, and the sun swam through the fog and I felt dizzy and Marisa<br />

shook her pretty bald head at me and buttered my toast. Whenever I<br />

asked her to, she’d tell me stories, such as how the Pretty Boys who<br />

peddled ass on Polk Street moved into the Pink Palace and then the<br />

Sleazy Attic and became the Bootboys so that they could die early<br />

because the Bootboys were such severe skinheads (“Almost all the<br />

skinheads are already dead,” sighed Marisa, “all the good ones”);<br />

and while Marisa went back into the kitchen to finish doing my<br />

dishes, her bootsister Thorn told me about how when she was in<br />

London her boyfriend Luigi got his eye popped out by the Italian<br />

Fascists, and then Marisa came back and told me about how when<br />

she was a thirteen-year-old girl in Chicago she started going with a<br />

skinhead named Sean, who was eighteen or twenty, and Marisa<br />

loved to hang out in Sean’s apartment, which must have resembled<br />

the workshop of a medieval armorer because scattered through its<br />

dark dirty chambers was a Camaro in pieces - hubcaps under the bed<br />

(so I imagined it), bucket seats emplaced against the living room<br />

walls for conveniently screwing Marisa and other girls, the shiny<br />

silver exhaust pipe by the door to hit enemies with, the carburetor<br />

serving to deploy old socks and dirty underwear and a black leather<br />

flight jacket to best advantage, while the gas tank was actively<br />

poised beside the window, still full of gasoline and ready to be<br />

hurled down onto the dirty icy street like a flying bomb; and<br />

presumably Marisa and Sean must have always been stepping over<br />

screws, and the windshield was in the cold dark moldy bathroom,<br />

covered with grime; and buckler-plates of chassis hung overhead in<br />

Sean’s bedroom, and the battery slowly leaked its acids through the<br />

floor; and now I have come to the end of all the auto parts that I know<br />

(except for the fan belt) - and Sean also possessed a stolen stop sign<br />

still in its cement base; possibly this was his hatstand. Although<br />

Marisa had not become Bootwoman Marisa yet, she loved and<br />

admired Skinhead Sean, so she tattooed Sean’s name on her body<br />

and started unrolling her secret capabilities by piercing her ears half<br />

35

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

a dozen times and doing fucked-up things to her hair, none of which<br />

things Marisa’s mother cared for, which was an incentive for Marisa<br />

to do them because Marisa’s mother treated her like a baby; when<br />

she used the leftover batter to make a final tiny pancake she’d say,<br />

“Oh, there’s a Marisa- sized pancake!” - and that really bothered<br />

Marisa. At that time, going to school started to bother her, too. Since<br />

she liked Sean better than she liked that listless two-hour commute<br />

from the North Side to the West Side, through cold dirty snow, with<br />

the cold wind blowing through the rusty railings, Marisa began<br />

sneaking down to the basement on those dark winter mornings<br />

instead of going to the bus, and when she heard the door-slam of her<br />

mother going to work Marisa would run back upstairs and dive into<br />

her warm bed and wait for Skinhead Sean to let himself in and hop<br />

into bed with her and watch TV until her mother came home at the<br />

end of the day, and then Marisa and Sean would go back to Sean’s<br />

metal-happy apartment. - Sean was very strong. One time after she<br />

and Sean broke up, Marisa was at this AOF show, and there was this<br />

skinhead band named The Alive going dwuuungg! on their bass<br />

guitars, and one of the guys in the band picked up on her, and Sean<br />

slammed his head against the wall. BAAAAAAM! until the blood<br />

spurted out, and Marisa thought that was the coolest thing, and then<br />

Sean threw him off the stage, and Marisa loved it. - Years later she<br />

met another Sean in Marin County when she and Thorn were over<br />

there trying to pop some virgin boy-cherries, and wily Marisa bet the<br />

new Sean two hundred dollars that she had his name tattooed on her<br />

body (which of course she did). Sean went for it. - Poor Sean! - Since<br />

he didn’t have the two hundred, he found himself under a universally<br />

acknowledged obligation to get her stoned on his dope for the rest of<br />

her life. *<br />

* Of course this was not quite as good a scam as the one perpetrated by the bum<br />

in the Panhandle who comes up to you and bets you that he has your name tattooed<br />

on the head of his dick regardless of who you are, so of course you fall for it and<br />

he unzips his jeans and flicks his thing, and there on the head of the glans, sure<br />

enough, are tattooed the words YOUR NAME.<br />

36

Coe Review • <strong>Issue</strong> <strong>22</strong><br />

“Now, tell me about how you decided to become<br />

Bootwoman Marisa,” I said, eating my eggs (eggs very lightly done,<br />

Marisa told me, are called “scared eggs”), while Marisa and Thorn<br />

sat at the table to keep me company, Thorn smoking and staring out<br />

the window and crushing her cigarette butts into a mug while Marisa<br />

drank tea (she never ate what she cooked at my house; she cooked it<br />

only for me).<br />

“Well, I didn’t decide to be Bootwoman Marisa,” she said,<br />

“it was sort of like a gift.” (At this remarkable commencement my<br />

mouth fell open, and I was in such a state of suspense that I almost<br />

became incontinent.)<br />

“How’s that?” I said. “They invited you?”<br />

“Okay. I don’t know if you knew me ‘way back when, but<br />

when I would hang out on Haight Street and shit, I used to wear like<br />

really funky makeup. Really funky makeup. I don’t know. I guess I<br />

had a much different attitude back then, about a lot of things. One<br />

day, Dee was like walking Rebel, right? And I saw her. So I was like,<br />

‘Hey, why don’t I go with you?’ And so we went, and we sat in the<br />

Park for hours and we talked. She was just like, ‘You look like a<br />

freak, Marisa! She just laid it right out, and she said, ‘You look like<br />

a freak, and none of us want to hang out with you if you’re gonna<br />

look like a freak.’ So, we went back to her house, and she sat me<br />

down, and she took off all of that freaky makeup, and she said, ‘Now<br />

that’s it. If you want to revolt against the world, you know, I hate the<br />

world, too, but it all comes from inside, and if you do it from the<br />

outside, people aren’t gonna respect you at all and you’re never<br />

gonna get anything you want.’ Then I sat down, and I took off all my<br />

stupid jewelry and shit, and the other Skinz were like, ‘That’s<br />

good!’” - Marisa pounded on the table. - “‘You have the potential to<br />

become a Bootwoman!’” - She pounded again, so that all the<br />

silverware jumped. - “And that’s what it was.”<br />

“You must have had your feelings hurt a little at first, when<br />

she said that about your makeup.”<br />

“Well, no,” said Marisa. “I didn’t really have any reason for<br />

doing it. I never did. I just did it. What the fuck. It’s just one of those<br />

things, you know.”<br />

“Did you feel different when you got your head shaved?”<br />

37