Supreme Court Agenda Setting in a System of Shared Powers Ryan ...

Supreme Court Agenda Setting in a System of Shared Powers Ryan ...

Supreme Court Agenda Setting in a System of Shared Powers Ryan ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

JLEO, V0 N0 1<br />

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong><br />

<strong>Ryan</strong> J. Owens †<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Government<br />

Harvard University<br />

I empirically exam<strong>in</strong>e separation <strong>of</strong> powers models to determ<strong>in</strong>e whether<br />

Congress and the president <strong>in</strong>fluence the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong>’s agenda. If the<br />

separation <strong>of</strong> powers <strong>in</strong>fluences the <strong>Court</strong>, it should decl<strong>in</strong>e review to cases<br />

that might lead it <strong>in</strong>to conflict with Congress and the president. The data<br />

suggest that the <strong>Court</strong> fails to heed the preferences <strong>of</strong> Congress and the<br />

president when sett<strong>in</strong>g its agenda. S<strong>in</strong>ce the agenda stage is the moment <strong>in</strong><br />

which the <strong>Court</strong> is most likely to show evidence <strong>of</strong> a separation <strong>of</strong> powers<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluence, the results here strongly suggest the <strong>Court</strong> is not systematically<br />

<strong>in</strong>fluenced by the political branches.<br />

1. Introduction<br />

Given the importance and controversial nature <strong>of</strong> many issues, a<br />

major conflict with Congress may sometimes be unavoidable; but,<br />

any battle, if it must be fought at all, should be fought at the time<br />

and under the political conditions most favorable to the cause <strong>of</strong><br />

the Justice. . . (Murphy, 1964, 157)<br />

Does the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> heed the preferences <strong>of</strong> the political branches dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

its decision mak<strong>in</strong>g process? Accord<strong>in</strong>g to a recent proposal aimed at<br />

impos<strong>in</strong>g term limits on United States <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> justices, the answer to<br />

this question is no. In a series <strong>of</strong> studies, Calabresi and L<strong>in</strong>dgren (2006a,b) call<br />

for a constitutional amendment to limit the tenure <strong>of</strong> <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> justices<br />

to one, non-renewable 18-year term. Chief among the authors’ concerns is the<br />

belief that the <strong>Court</strong> as currently constituted evades democratic checks. As<br />

an empirical matter, however, the answer to this question is wide open. Does<br />

the <strong>Court</strong> ignore the preferences <strong>of</strong> Congress and the president when mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

decisions? Is the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> “completely divorced from democratic ac-<br />

†<strong>Ryan</strong> Owens (ryan owens@gov.harvard.edu) is an Assistant Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Government at Harvard<br />

University. I would like to thank <strong>Ryan</strong> Black, Bill Lowry, Andrew Mart<strong>in</strong>, Jim Spriggs, and<br />

Steve Smith for helpful comments. I also wish to thank Anna Harvey and Barry Friedman for<br />

provid<strong>in</strong>g their data. I thank Anna Harvey for her comments on an earlier draft <strong>of</strong> this paper. The<br />

Center for Empirical Research <strong>in</strong> the Law also deserves praise for its generous f<strong>in</strong>ancial assistance.<br />

The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization, Vol. 0, No.0,<br />

doi:10.1093/jleo/ewmxxx<br />

c○ The Author 2007. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf <strong>of</strong> Yale University.<br />

All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org

2 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

countability” and, therefore, “an affront to the system <strong>of</strong> checks and balances”<br />

(Calabresi and L<strong>in</strong>dgren, 2006a, 813)?<br />

Numerous studies exam<strong>in</strong>e whether justices rule differently when they anticipate<br />

legislative resistance to their decisions (Segal, 1997; Hansford and<br />

Damore, 2000; Sala and Spriggs, 2004) but they are limited <strong>in</strong> important ways<br />

that prevent us from understand<strong>in</strong>g whether the <strong>Court</strong> truly is as <strong>in</strong>dependent<br />

as Calabresi and L<strong>in</strong>dgren (2006a,b) fear, or, whether it is a strategic separation<br />

<strong>of</strong> powers (SOP) actor that decides cases <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with majoritarian preferences.<br />

More specifically, these studies are limited by their exclusive focus<br />

on the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong>’s merits decisions (but see Owens, 2008). Because the<br />

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> sets its own agenda—and does so <strong>in</strong> private—it might decl<strong>in</strong>e<br />

to review cases likely to engender hostility from the political branches. That<br />

is, the <strong>Court</strong> can avoid trouble simply by decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to decide a case. What may<br />

look at the merits stage like a <strong>Court</strong> act<strong>in</strong>g without regard to legislative and executive<br />

preferences may, <strong>in</strong> fact, be a <strong>Court</strong> that has already filtered out cases<br />

strategically. What is needed, then, is an exam<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> whether the separation<br />

<strong>of</strong> powers <strong>in</strong>fluences the <strong>Court</strong>’s agenda decisions.<br />

In this paper, I exam<strong>in</strong>e whether the <strong>Court</strong> strategically sets its agenda <strong>in</strong> a<br />

separation <strong>of</strong> powers context. I analyze 430 petitions for review and appeals<br />

filed with the <strong>Court</strong> between its 1953 and 1993 terms. I test the empirical implications<br />

<strong>of</strong> various theoretical SOP models.<br />

My results could not be clearer. Across every model I test, the <strong>Court</strong> failed<br />

to follow the separation <strong>of</strong> powers prediction. Simply put, the <strong>Court</strong> sets its<br />

agenda without regard to congressional and legislative preferences. Given that<br />

the agenda sett<strong>in</strong>g process is the stage <strong>in</strong> which the <strong>Court</strong> is most likely to<br />

show signs <strong>of</strong> strategic SOP behavior, these results cast serious doubt on strategic<br />

SOP theories. The results further speak to normative questions regard<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the <strong>Court</strong>’s role <strong>in</strong> contemporary government. S<strong>in</strong>ce “a central problem <strong>of</strong> representative<br />

democracy is how to ensure that policy decisions are responsive<br />

to the <strong>in</strong>terests or preferences <strong>of</strong> citizens,” (McCubb<strong>in</strong>s, Noll and We<strong>in</strong>gast,<br />

1987, 243) such a counter-majoritarian force must be reconciled with evolv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

concepts <strong>of</strong> democratic rule.<br />

The paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 describes the <strong>Court</strong>’s agendasett<strong>in</strong>g<br />

process. Section 3 then theorizes how a forward-th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Supreme</strong><br />

<strong>Court</strong> might set its agenda <strong>in</strong> an SOP context. Section 4 models the conditions<br />

under which the <strong>Court</strong> might grant or deny cases <strong>in</strong> such a context. Section 5<br />

expla<strong>in</strong>s the data and methods I use to test the strategic SOP theory. Section 6<br />

presents my results and section 7 concludes.<br />

2. The <strong>Agenda</strong>-<strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Process<br />

When a party <strong>in</strong> a lower court loses her dispute and wants the <strong>Supreme</strong><br />

<strong>Court</strong> to review her case, she files a petition for a writ <strong>of</strong> certiorari (“cert”) or an<br />

appeal with the United States <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> Clerk. After check<strong>in</strong>g the petition<br />

or appeal to ensure it meets m<strong>in</strong>imum fil<strong>in</strong>g requirements, the Clerk sends<br />

the document to each <strong>of</strong> the justices’ chambers. The petition is then randomly

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 3<br />

assigned to one <strong>of</strong> the law clerks <strong>in</strong> the “cert pool,” who is charged with writ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary memo (a “pool memo”) which summarizes the proceed<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong><br />

the lower courts, discusses all claims made <strong>in</strong> the petition, and concludes with<br />

a recommendation for how the <strong>Court</strong> should treat the petition. 1 The pool memo<br />

is then distributed to the chambers <strong>of</strong> the participat<strong>in</strong>g justices.<br />

After review<strong>in</strong>g the pool memos, the Chief Justice makes an <strong>in</strong>itial determ<strong>in</strong>ation<br />

<strong>of</strong> the petitions that he th<strong>in</strong>ks merit some discussion by the <strong>Court</strong>. That<br />

is, on a roll<strong>in</strong>g basis as the petitions come <strong>in</strong>, the Chief will compile a “discuss<br />

list” <strong>of</strong> all the petitions that he believes might be worthy <strong>of</strong> a grant—or at least<br />

some discussion as to their “certworth<strong>in</strong>ess.” The Chief circulates this list to<br />

the Associate Justices who, <strong>in</strong> turn, can add petitions that they th<strong>in</strong>k merit the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>’s discussion. No justice can remove a petition put on the list by a colleague,<br />

however. A petition that makes the discuss list receives at least some<br />

form <strong>of</strong> discussion by the <strong>Court</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g conference, regardless <strong>of</strong> whether it is<br />

eventually granted or denied review. A petition that does not make the discuss<br />

list, however, is summarily denied—it receives no discussion by the <strong>Court</strong> and<br />

is denied unanimously.<br />

The <strong>Court</strong> meets <strong>in</strong> private conference roughly once every two weeks to<br />

determ<strong>in</strong>e which cases it will hear. Dur<strong>in</strong>g these conferences, the justices vote<br />

on whether to grant or deny review to each petition on the discuss list. Before<br />

the justices vote, however, the justice who placed the petition on the discuss<br />

list will lead <strong>of</strong>f a brief discussion about it, stat<strong>in</strong>g why s/he placed the case on<br />

the list as well as his or her views regard<strong>in</strong>g the importance <strong>of</strong> the case. That<br />

justice then casts an agenda vote. In order <strong>of</strong> seniority, the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g justices<br />

do the same. Only if four or more justices vote to grant review does the case<br />

proceed to the merits stage. 2 Cert votes are entirely discretionary and, unless<br />

divulged by the personal papers <strong>of</strong> a former justice, are completely secret. This<br />

secrecy, plus the <strong>Court</strong>’s lack <strong>of</strong> formal requirements for tak<strong>in</strong>g cases, set the<br />

stage for strategic agenda sett<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

Indeed, justices cast strategic agenda-sett<strong>in</strong>g votes by vot<strong>in</strong>g to grant review<br />

to cases when the policy they expect the <strong>Court</strong> to make is better than<br />

the status quo (Black and Owens forthcom<strong>in</strong>g; see also Caldeira et al. 1999).<br />

Similarly, Benesh, Brenner and Spaeth (2002), Boucher and Segal (1995), and<br />

Brenner (1979) show how affirm-m<strong>in</strong>ded justices strategically anticipate the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>’s likely merits rul<strong>in</strong>g so as to avoid creat<strong>in</strong>g legal policy that is worse<br />

than the status quo. Other research f<strong>in</strong>ds that the <strong>Court</strong> is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly likely to<br />

grant review as the number <strong>of</strong> briefs amicus curiae filed either support<strong>in</strong>g or<br />

1. The cert pool was created <strong>in</strong> 1972 as way to reduce the amount <strong>of</strong> cert petition work done <strong>in</strong><br />

each <strong>in</strong>dividual chamber. Prior to its creation, each chamber <strong>in</strong>dependently reviewed every petition<br />

for cert (Ward and Weiden, 2006, 118). At the time <strong>of</strong> the pool’s creation, William J. Brennan,<br />

William O. Douglas, Thurgood Marshall, and Potter Stewart decl<strong>in</strong>ed to participate <strong>in</strong> the pool.<br />

With the exception <strong>of</strong> Justices John Paul Stevens and Samuel Alito, each new justice to jo<strong>in</strong> the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce the pool’s creation have elected to participate <strong>in</strong> it.<br />

2. Technically, the <strong>Court</strong> will hear a case with three grant votes plus a Jo<strong>in</strong>-3 vote. It will not<br />

grant review, however, if just two justices vote to grant and two vote to Jo<strong>in</strong>-3 (Black and Owens,<br />

N.d.).

4 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

oppos<strong>in</strong>g review <strong>in</strong>creases (Caldeira and Wright, 1988; Caldeira, Wright and<br />

Zorn, 1999), when the lower courts are <strong>in</strong> conflict over the correct application<br />

or <strong>in</strong>terpretation <strong>of</strong> federal law, and when other important legal considerations<br />

exist.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> these studies have served to further our understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> the conditions<br />

under which the <strong>Court</strong> sets its agenda. Nevertheless, they tell us noth<strong>in</strong>g<br />

about whether congressional and executive preferences <strong>in</strong>fluence the manner<br />

<strong>in</strong> which the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> sets its agenda. Do congressional and executive<br />

preferences cause the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> to decl<strong>in</strong>e to review cases? In what follows,<br />

I address these questions.<br />

3. Expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Strategic SOP <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong><br />

Exist<strong>in</strong>g studies which analyze whether the separation <strong>of</strong> powers <strong>in</strong>fluences<br />

the <strong>Court</strong> arrive at mixed conclusions with most, however, f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g no evidence<br />

<strong>of</strong> an SOP effect (Segal, 1997; Segal and Westerland, 2005; Sala and Spriggs,<br />

2004; Spriggs and Hansford, 2001). The few studies that observe an SOP <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

are limited <strong>in</strong> important ways which make their conclusions somewhat<br />

suspect. For example, Hansford and Damore (2000) f<strong>in</strong>d that some justices<br />

moderate their votes based on legislative preferences. Analyz<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Court</strong>’s<br />

statutory decisions from 1963 to 1995, the authors f<strong>in</strong>d that justices more conservative<br />

than the president and both judiciary committees cast more liberal<br />

votes than they would <strong>in</strong> a non-SOP context. On the other hand, liberal outlier<br />

justices were no more likely to rule conservatively to avoid legislative rebuke.<br />

These results do not square with the SOP model exam<strong>in</strong>ed however, as the<br />

model asserted that both types <strong>of</strong> outlier justices would behave strategically.<br />

Moreover, the study uses preference estimates for the different branches that<br />

do not scale, limit<strong>in</strong>g the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs. 3<br />

Spiller and Gely (1992) f<strong>in</strong>d that the <strong>Court</strong> renders more pro-labor decisions<br />

as Congress becomes <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly liberal; yet, the study does not <strong>in</strong>clude the<br />

president as a pivotal actor and relies on ADA scores as proxies <strong>of</strong> legislative<br />

ideology. These scores have been attacked as poor surrogates <strong>of</strong> congressional<br />

preferences (B<strong>in</strong>der, Lawrence and Maltzman, 1999; Snyder, 1992).<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, Harvey and Friedman (2006) f<strong>in</strong>d that the 1994 Republican Revolution,<br />

which provided the <strong>Court</strong> with a friendly Congress, played a key role<br />

<strong>in</strong> the <strong>Court</strong>’s <strong>in</strong>creased proclivity to strike federal laws after 1994. Still, the<br />

substantive impact <strong>of</strong> their SOP variable is weak: The predicted probability<br />

that the <strong>Court</strong> would strike a federal statute <strong>in</strong>creased from 0.00036 <strong>in</strong> 1987 to<br />

0.00137 <strong>in</strong> 2000 as the result <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Court</strong>’s new position between key pivots<br />

<strong>in</strong> Congress. What is more, s<strong>in</strong>ce the study does not <strong>in</strong>clude the president as<br />

a pivotal actor (other than <strong>in</strong> the Filibuster-Veto model), it is unclear whether<br />

these results are the product <strong>of</strong> an artificially small legislative equilibrium. 4<br />

3. Justice ideology is measured as the percent <strong>of</strong> liberal votes a justice cast, while legislative<br />

and executive preferences are coded us<strong>in</strong>g DW-NOMINATE scores (see also Bergara, Richman<br />

and Spiller, 2003).<br />

4. The study is, however, an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g piece with a unique approach to the separation <strong>of</strong>

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 5<br />

In short, while these studies have provided important <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to the <strong>Court</strong><br />

and its role <strong>in</strong> a system <strong>of</strong> shared power, they are limited <strong>in</strong> potentially important<br />

ways. Perhaps the most critical reason for question<strong>in</strong>g whether the <strong>Court</strong><br />

actually plays the separation <strong>of</strong> powers game, however, is the fact that virtually<br />

no study has exam<strong>in</strong>ed how legislative and executive preferences <strong>in</strong>fluence<br />

the <strong>Court</strong>’s agenda decisions. If the <strong>Court</strong> strategically sets its agenda so as to<br />

avoid conflicts with Congress and the president, exist<strong>in</strong>g work focus<strong>in</strong>g on<br />

the merits stage is unlikely to uncover the hidden effects <strong>of</strong> the separation <strong>of</strong><br />

powers—much sophisticated behavior is likely to have occurred already (Murphy,<br />

1964).<br />

Epste<strong>in</strong>, Segal and Victor (2002) is the only currently published study to analyze<br />

SOP <strong>in</strong>fluences on the <strong>Court</strong>’s agenda decisions. Epste<strong>in</strong> and her coauthors<br />

exam<strong>in</strong>ed the percent <strong>of</strong> statutory <strong>in</strong>terpretation and constitutional <strong>in</strong>terpretation<br />

cases that made the <strong>Court</strong>’s docket over time. They argued that because<br />

the <strong>Court</strong>’s statutory <strong>in</strong>terpretation decisions are more easily overridden<br />

by Congress than its constitutional decisions, its docket should consist <strong>of</strong> fewer<br />

statutory <strong>in</strong>terpretation cases and more judicial review cases when it is ideologically<br />

at odds with Congress. The study f<strong>in</strong>ds that the <strong>Court</strong>’s docket does<br />

<strong>in</strong> fact conta<strong>in</strong> a higher percentage <strong>of</strong> statutory <strong>in</strong>terpretation cases dur<strong>in</strong>g periods<br />

<strong>of</strong> legislative constra<strong>in</strong>t. Nevertheless, it too uses ADA scores to measure<br />

congressional preferences and focuses only on cases the <strong>Court</strong> decided to hear,<br />

lead<strong>in</strong>g to questions <strong>of</strong> selection bias.<br />

Build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>f this analysis, Owens (2008) exam<strong>in</strong>ed the separation <strong>of</strong> powers<br />

conditions under which <strong>in</strong>dividual justices vote to grant or deny review. Owens<br />

(2008) analyzed archival data to exam<strong>in</strong>e whether the separation <strong>of</strong> powers <strong>in</strong>fluences<br />

<strong>in</strong>dividual justices’ agenda votes. The results <strong>of</strong> the study suggest that<br />

legislative and executive preferences failed to <strong>in</strong>fluence justices’ votes. Nevertheless,<br />

Owens (2008) assumes that transaction costs for pass<strong>in</strong>g legislation<br />

are zero, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that any policy set by the <strong>Court</strong> outside the legislative<br />

equilibrium will be overturned. While this assumption follows on the heels <strong>of</strong><br />

exist<strong>in</strong>g work, transaction costs may matter. If so, a <strong>Court</strong> that is constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

under a zero-transaction-cost approach may actually be unconstra<strong>in</strong>ed under<br />

one that <strong>in</strong>cludes such costs. The result could lead to erroneously reject<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the SOP hypothesis when, <strong>in</strong> fact, it is true. Thus, <strong>in</strong> what follows, I exam<strong>in</strong>e<br />

the conditions under which legislative and executive preferences <strong>in</strong>fluence the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>’s decision to review a case while <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g the notion <strong>of</strong> transaction<br />

costs <strong>in</strong>to the models.<br />

My theoretical start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong> this endeavor is that justices are seekers <strong>of</strong><br />

legal policy who want to etch their policy preferences <strong>in</strong>to law. “Most justices,<br />

<strong>in</strong> most cases, pursue policy; that is, they want to move the substantive content<br />

<strong>of</strong> law as close as possible to their preferred position” (Epste<strong>in</strong> and Knight,<br />

1998, 23). Justices are not unconstra<strong>in</strong>ed actors, however. They must pursue<br />

their goals <strong>in</strong> an environment <strong>in</strong> which their choices are a function not only<br />

<strong>of</strong> their own preferences, but also the preferences and likely reactions <strong>of</strong> their<br />

powers.

6 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

colleagues (see, e.g. Maltzman, Spriggs and Wahlbeck, 2000) and, perhaps,<br />

the political branches (Epste<strong>in</strong> and Knight, 1998; Rosenberg, 1991).<br />

Of course, this begs the question, why would the <strong>Court</strong> follow congressional<br />

and presidential preferences? One answer to this question turns on the appo<strong>in</strong>tment<br />

process. Dahl (1957) argues that judicial decision mak<strong>in</strong>g is majoritarian<br />

because presidents and senators, on average, nom<strong>in</strong>ate and confirm a new justice<br />

every two years. S<strong>in</strong>ce politicians can only be expected to appo<strong>in</strong>t justices<br />

whose ideologies track their own, the <strong>Court</strong> should be composed <strong>of</strong> justices<br />

sympathetic to the policy aims <strong>of</strong> the rul<strong>in</strong>g majority (Rehnquist, 1987). As a<br />

result, the <strong>Court</strong> rarely—if ever—will render decisions <strong>in</strong> a manner counter to<br />

the majority’s policy goals. Indeed, this assumption largely undergirds recent<br />

attacks on lifetime tenure (Calabresi and L<strong>in</strong>dgren, 2006a).<br />

A second answer—the one made by strategic SOP theorists—argues that the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> will buckle under congressional and executive preferences because the<br />

political branches have the constitutional authority to punish the <strong>Court</strong> and pass<br />

legislation that alters its policies (Epste<strong>in</strong>, Knight and Mart<strong>in</strong>, 2001). Congress<br />

can <strong>in</strong>itiate and support constitutional amendments to overturn judicial decisions.<br />

It can reduce the <strong>Court</strong>’s budget, alter its composition, strip it <strong>of</strong> jurisdiction,<br />

regulate <strong>Court</strong> procedure, hold judicial salaries constant, and impeach justices<br />

(George and Epste<strong>in</strong>, 1992). Perhaps most importantly, Congress can pass<br />

legislation that overrides <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> decisions. S<strong>in</strong>ce 1975, each Congress<br />

has overridden an average <strong>of</strong> roughly twelve statutory <strong>in</strong>terpretation decisions<br />

and, dur<strong>in</strong>g the same time period, nearly half <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Court</strong>’s decisions received<br />

some type <strong>of</strong> congressional hear<strong>in</strong>g (Eskridge, 1991; Ignagni and Meernik,<br />

1994). These data suggest that Congress has the ability to respond to <strong>Supreme</strong><br />

<strong>Court</strong> decisions it dislikes and, if it so chooses, to act swiftly.<br />

Presidents also, the story goes, may <strong>in</strong>fluence the <strong>Court</strong>. “Even the members<br />

<strong>of</strong> the <strong>Court</strong> not appo<strong>in</strong>ted by the sitt<strong>in</strong>g president understand that the president’s<br />

status as a nationally elected <strong>of</strong>ficial and his position at the re<strong>in</strong>s <strong>of</strong> every<br />

executive branch agency make him a formidable foe under any circumstance”<br />

(Yal<strong>of</strong>, 2005, 501). Presidents can refuse to enforce the <strong>Court</strong>’s decisions and<br />

order Cab<strong>in</strong>et Secretaries and other high-rank<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>ficials to ignore them. They<br />

can unilaterally create their own executive policies and shift the policy status<br />

quo (Moe and Howell, 1999; Black et al., 2007), mobilize <strong>in</strong>terest groups to<br />

attack and underm<strong>in</strong>e the <strong>Court</strong>’s decisions (Peterson, 1992), and use their<br />

agenda-sett<strong>in</strong>g power to focus public scrut<strong>in</strong>y on judicial decisions. And, <strong>of</strong><br />

course, they can sign or veto override legislation.<br />

In sum, strategic SOP theorists argue that the comb<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> these powers—<br />

even the threat <strong>of</strong> their use—will force the <strong>Court</strong> to anticipate how Congress<br />

and the president will respond to its decisions and make policy <strong>in</strong> compliance<br />

with majoritarian preferences. (Spiller and Gely, 1992; Bergara, Richman and<br />

Spiller, 2003; Harvey and Friedman, 2006; Epste<strong>in</strong> and Knight, 1998). Accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to these scholars, if the <strong>Court</strong> (i.e., the <strong>Court</strong> median) perceives that<br />

by vot<strong>in</strong>g for its most preferred alternative it will create policy out <strong>of</strong> step with<br />

key policymakers, it will moderate its decision so as to make policy that is<br />

more favorable to them. Influence from the elected branches, then, forces the

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 7<br />

<strong>Court</strong> <strong>in</strong>to majoritarian compliance. Largely ignored from these analyses, however,<br />

is whether the <strong>Court</strong> will simply decl<strong>in</strong>e to review cases that will place<br />

the <strong>Court</strong> at risk.<br />

4. Model<strong>in</strong>g a Constra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>Court</strong><br />

I model the conditions under which the <strong>Court</strong> might grant or deny review to<br />

cases due to an SOP constra<strong>in</strong>t. As I describe more fully below, two conditions<br />

must be met before the political branches can constra<strong>in</strong> the <strong>Court</strong>. First, the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> median must have an ideal po<strong>in</strong>t outside the legislative equilibrium—the<br />

policy space <strong>in</strong> which there are no alternative po<strong>in</strong>ts that make all legislative<br />

actors at least as well <strong>of</strong>f (Hett<strong>in</strong>ger and Zorn, 2005, 7). Second, the <strong>Court</strong>’s<br />

decision must make Congress worse <strong>of</strong>f than the exist<strong>in</strong>g status quo. When<br />

these two conditions are met, the <strong>Court</strong> will be constra<strong>in</strong>ed.<br />

The models used to test the strategic SOP theory make the follow<strong>in</strong>g assumptions:<br />

All actors have cont<strong>in</strong>uous, s<strong>in</strong>gle-peaked, symmetric preferences<br />

on a unidimensional policy scale and prefer policy that is closest to their ideal<br />

po<strong>in</strong>ts (Sala and Spriggs, 2004). There exists a status quo that can be measured<br />

on the same unidimensional scale. All actors know each others’ preferences<br />

and the policy location <strong>of</strong> the status quo (Harvey and Friedman, 2006). S<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

the actors’ preferences are categorized fully by the model, they will choose<br />

equilibrium strategies even when their votes are not pivotal (Sala and Spriggs,<br />

2004). Further, the <strong>Court</strong> can be expected to set policy at the median justice’s<br />

ideal po<strong>in</strong>t (Mart<strong>in</strong>, Qu<strong>in</strong>n and Epste<strong>in</strong>, 2005). 5 The pivotal legislative actors<br />

will pursue override legislation only when the <strong>Court</strong> changes policy <strong>in</strong> a manner<br />

that is worse for them. 6 And, f<strong>in</strong>ally, justices want to avoid legislative overrides.<br />

7<br />

5. This assumption is grounded <strong>in</strong> theoretical and empirical work. Hammond, Bonneau and<br />

Sheehan (2005) proposed what they called the “Bench Median model.” The model argues that after<br />

a free competition among the justices over draft op<strong>in</strong>ions, the median justice’s position w<strong>in</strong>s out.<br />

The equilibrium result is that no matter who drafts the majority op<strong>in</strong>ion, the <strong>Court</strong>’s policy reflects<br />

the preferences <strong>of</strong> the median justice (see also Mart<strong>in</strong>, Qu<strong>in</strong>n and Epste<strong>in</strong>, 2005). Recent empirical<br />

work provides support for the Bench Median model (Bonneau et al., 2007). While Bonneau et al.<br />

(2007) also propose an “<strong>Agenda</strong> Control” model which suggests that the policy content <strong>of</strong> the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>’s op<strong>in</strong>ions is determ<strong>in</strong>ed by the preferences <strong>of</strong> the op<strong>in</strong>ion author, conditioned on his or her<br />

need to acquire a majority to set precedent, that model is unhelpful at the agenda-sett<strong>in</strong>g stage<br />

because justices have no a priori knowledge <strong>of</strong> who will write the majority op<strong>in</strong>ion (Hammond,<br />

Bonneau and Sheehan, 2005, 224). It is worth not<strong>in</strong>g, however, that even under the <strong>Agenda</strong> Control<br />

model, the median justice’s preferences play a critical role by constra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the location <strong>of</strong> the<br />

op<strong>in</strong>ion to the median justice’s preferred-to set <strong>of</strong> the status quo, mak<strong>in</strong>g the median absolutely<br />

essential.<br />

6. As stated above, this assumption deviates from the assumption made by Owens (2008), who<br />

assumed zero transaction costs associated with override legislation.<br />

7. This assumption accords with the assumptions made <strong>in</strong> nearly all exist<strong>in</strong>g SOP models (see,<br />

e.g. Segal, 1997; Spiller and Gely, 1992; Gely and Spiller, 1990; Harvey and Friedman, 2006; Sala<br />

and Spriggs, 2004; Bergara, Richman and Spiller, 2003). An <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>of</strong> studies analyzes<br />

how justices might enlist the aid <strong>of</strong> Congress <strong>in</strong> the pursuit <strong>of</strong> their goals (Spiller and Tiller, 1996;<br />

Hausegger and Baum, 1999).

8 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

(A) Inside Legislative Equilibrium<br />

H J S P<br />

(B) Outside Legislative Equilibrium<br />

H S P J<br />

Figure 1. Context and the Separation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Powers</strong>. H=House. S=Senate. P =President.<br />

J=<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong>. In this Figure, the House is the Left Pivot and the President is the<br />

Right Pivot.<br />

4.1 The Median Justice and the Legislative Equilibrium<br />

The first condition that must be met for the <strong>Court</strong> to behave strategically<br />

turns on the location <strong>of</strong> the median justice relative to the legislative equilibrium.<br />

Figure 1 provides a graphical explanation. The House, Senate, President,<br />

and <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> are all placed along this spectrum. The <strong>Court</strong>’s relation to<br />

these actors is critically important. Figure 1A shows a <strong>Court</strong> that is <strong>in</strong>side the<br />

legislative equilibrium. The <strong>Court</strong> <strong>in</strong> this example is more conservative than<br />

the House (the Left Pivot) and Senate but is less conservative than the president<br />

(the Right Pivot). Under this configuration, the <strong>Court</strong> can set policy at<br />

its ideal po<strong>in</strong>t, J, regardless <strong>of</strong> where the status quo is located because J is<br />

protected. If the House tried to pass override legislation anywhere to the left <strong>of</strong><br />

J the president (and Senate ) would block it. Conversely, if the president proposed<br />

override legislation to the right <strong>of</strong> J, the House would block it. Stalemate<br />

results, with the <strong>Court</strong> able to pursue its s<strong>in</strong>cerely held policy goals. 8<br />

Figure 1B represents a situation <strong>in</strong> which the <strong>Court</strong> may be constra<strong>in</strong>ed because<br />

it is outside the legislative equilibrium. Here, the <strong>Court</strong> is more conservative<br />

than both the Left and Right Pivots and may be vulnerable to override<br />

and punitive legislation, depend<strong>in</strong>g on where the status quo is located. That is,<br />

whether the political branches pursue such legislation depends on the location<br />

<strong>of</strong> the status quo.<br />

4.2 Policy Change and the Status Quo<br />

If the <strong>Court</strong> median falls outside the legislative equilibrium, the <strong>Court</strong> may<br />

f<strong>in</strong>d itself <strong>in</strong> an unconstra<strong>in</strong>ed, semi-constra<strong>in</strong>ed, or constra<strong>in</strong>ed regime, depend<strong>in</strong>g<br />

on the location <strong>of</strong> the status quo. 9 Figures 2 and 3 illustrate. J represents<br />

the median justice’s ideal po<strong>in</strong>t. SQ represents the status quo policy the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> is be<strong>in</strong>g asked to review. L is the leftmost pivotal member <strong>of</strong> the legislative<br />

process. R is the rightmost legislative pivot. SQ ∗ L represents the Left<br />

8. The current example ignores the veto override. I test the impact <strong>of</strong> the veto override below.<br />

9. For a well-developed discussion on the concept <strong>of</strong> “regimes,” see Moraski and Shipan<br />

(1999).

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 9<br />

Regime 1—Unconstra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

W R (SQ)<br />

W L (SQ)<br />

*<br />

SQ J L R SQ L<br />

*<br />

SQ R<br />

Regime 2—Constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

W R (SQ)<br />

W L (SQ)<br />

J SQ L R SQ L<br />

*<br />

SQ R<br />

*<br />

Figure 2. Context and the Separation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Powers</strong>. J=<strong>Court</strong> Median. SQ=Status<br />

Quo. L=Left Pivot. R=Right Pivot. SQ ∗ L =Left Pivot’s Indifference Po<strong>in</strong>t Vis-a-vis SQ.<br />

SQ ∗ R =Right Pivot’s Indifference Po<strong>in</strong>t Vis-a-vis SQ. W L(SQ) is the “preferred-to set” <strong>of</strong><br />

SQ for the Left Pivot. W R (SQ) is the “preferred-to set” <strong>of</strong> SQ for the Right Pivot.<br />

Pivot’s <strong>in</strong>difference po<strong>in</strong>t relative to the status quo. That is, it reflects the policy<br />

that the Left Pivot enjoys just as much as the status quo. SQ ∗ R is the Right<br />

Pivot’s <strong>in</strong>difference po<strong>in</strong>t relative to the status quo. W L (SQ) is the “preferredto<br />

set” <strong>of</strong> SQ for the Left Pivot—the set <strong>of</strong> policies that the Left Pivot prefers<br />

to SQ (Bonneau et al., 2007, 893). W R (SQ) is the “preferred-to set” <strong>of</strong> SQ<br />

for the Right Pivot—the set <strong>of</strong> policies that the Right Pivot prefers to SQ.<br />

In Regime 1, even though the median justice resides outside the legislative<br />

equilibrium, the <strong>Court</strong> is unconstra<strong>in</strong>ed and can render a decision at its ideal<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t. That is, should the <strong>Court</strong> grant review to the case, it will be able to<br />

modify the status quo to its ideal po<strong>in</strong>t, J. Why is this the case? The <strong>Court</strong><br />

resides with<strong>in</strong> both the Left and Right Pivot’s preferred-to sets relative to SQ.<br />

Thus, a s<strong>in</strong>cere decision by the <strong>Court</strong> will make both Pivots better <strong>of</strong>f than the<br />

status quo. When the <strong>Court</strong> renders its decision at J, it shifts policy closer to<br />

both pivots. The result is an improvement for the key legislative actors. 10 The<br />

political actors will not respond with override legislation <strong>in</strong> such a scenario.<br />

Because the <strong>Court</strong>’s ultimate policy J is better than the status quo for the <strong>Court</strong><br />

and the key Pivots, it will grant review.<br />

In Regime 2, the <strong>Court</strong> is constra<strong>in</strong>ed and will decl<strong>in</strong>e to review the case.<br />

The <strong>Court</strong> is more liberal than the status quo which, <strong>in</strong> turn, is more liberal<br />

than the Left and Right Pivots. If the <strong>Court</strong> granted review to the case and rendered<br />

a decision at J, the result would be a net policy loss for the key pivots.<br />

10. I assume that transaction costs prevent Congress and the president from overrid<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>’s decision—that Congress and the president will not seek to override judicial decisions that<br />

they regard as an improvement over the status quo. This assumption addresses the endogeneity<br />

issue <strong>of</strong> why the status quo is where it is. That is, it addresses the fact that Congress and the<br />

president simply found themselves unable to change the status quo to a policy with<strong>in</strong> the current<br />

legislative equilibrium.

10 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

Because the <strong>Court</strong> has taken a status quo policy and made it worse for the political<br />

branches, they will respond with override legislation that sets new policy<br />

somewhere on LR. Because the policy result<strong>in</strong>g from this override would represent<br />

a policy loss for the <strong>Court</strong>—as well as damage to its legitimacy—the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> will deny review to the case. 11<br />

Regime 3 shows a semi-constra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>Court</strong>. In this regime, the <strong>Court</strong>’s ability<br />

to set policy is dependent on the pivots’ preferred-to sets. Look first at SQ 1 .<br />

Assume that the <strong>Court</strong> is represented by J 1 . In this example, the <strong>Court</strong> could<br />

set policy at its ideal po<strong>in</strong>t because it falls with<strong>in</strong> both pivots’ preferred-to sets<br />

relative to SQ 1 . That is, the <strong>Court</strong>’s new policy would be an improvement for<br />

both the Left and the Right Pivots. Now, however, assume that after personnel<br />

change, the <strong>Court</strong> median is represented by J 2 . If the <strong>Court</strong> tried to set policy<br />

at J 2 , its decision would be vulnerable to a legislative override. To be sure,<br />

sett<strong>in</strong>g policy at J 2 would make the Right Pivot better <strong>of</strong>f. Nevertheless, the<br />

policy shift would be worse for the Left Pivot. In response, the Left Pivot<br />

would propose legislation somewhere on LR that makes it and the Right Pivot<br />

better <strong>of</strong>f than J 2 . Anticipat<strong>in</strong>g this response, the <strong>Court</strong> would simply render<br />

its decision at SQ L 1 ∗ . This is the location <strong>in</strong> policy space that makes R and<br />

J 2 better <strong>of</strong>f, and L no worse <strong>of</strong>f than SQ. Even though the <strong>Court</strong> cannot set<br />

policy at J 2 , its policy decision at SQ L 1 ∗ still reflects a net policy ga<strong>in</strong> for the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>. As such, it would vote to grant review.<br />

Now, assume that the status quo is SQ 2 rather than SQ 1 and that the <strong>Court</strong>’s<br />

median is aga<strong>in</strong> J 1 . The <strong>Court</strong> <strong>in</strong> this scenario would be forced to render a decision<br />

at R. If the <strong>Court</strong> rendered a decision at J 1 , it would, <strong>of</strong> course, improve<br />

policy for the Right Pivot but make a worse policy for the Left Pivot. In response,<br />

the Left Pivot would propose override legislation somewhere on LR.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce the legislation L strategically proposes will always be better for R, R<br />

would agree to the override. To avoid this response, the <strong>Court</strong> would be forced<br />

to render a decision on the merits at R. As this is the Right Pivot’s ideal po<strong>in</strong>t,<br />

noth<strong>in</strong>g L proposes would lead R to move policy away from the <strong>Court</strong>’s decision.<br />

The <strong>Court</strong>’s policy, then, survives any override attempt. In the end, while<br />

the <strong>Court</strong> cannot set policy at its ideal po<strong>in</strong>t (either J 1 or J 2 ), the equilibrium<br />

policy it adopts nevertheless will be an improvement for the <strong>Court</strong>. Consequently,<br />

it will grant review to cases <strong>in</strong> this regime.<br />

Regime 4 also shows a semi-constra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>Court</strong>. Look first at a <strong>Court</strong> whose<br />

median is J 1 . If the <strong>Court</strong> rendered a decision at J 1 , it would make both legislative<br />

pivots worse <strong>of</strong>f than the status quo and they, <strong>in</strong> turn, would pass override<br />

legislation (which could, quite conceivably be worse than the exist<strong>in</strong>g status<br />

quo for the <strong>Court</strong>). 12 The <strong>Court</strong> at J 1 , then, would be constra<strong>in</strong>ed to render a<br />

11. Of course, the <strong>Court</strong> could grant review and set policy just to the right <strong>of</strong> SQ (a po<strong>in</strong>t<br />

with<strong>in</strong> both pivots’ preferred-to sets). While a majority <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Court</strong> is not likely to grant review<br />

<strong>in</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> case because it would make worse policy for them, a m<strong>in</strong>ority <strong>of</strong> justices us<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the Rule <strong>of</strong> Four could force the case on the <strong>Court</strong>’s docket to <strong>in</strong>duce such a shift. Nevertheless,<br />

these four justices would be little assuaged by the grant s<strong>in</strong>ce the <strong>Court</strong> would only shift policy<br />

marg<strong>in</strong>ally. They are not likely to waste their resources on such a trivial policy shift.<br />

12. Even if the policy that results from the override is better for the <strong>Court</strong> than the status quo,

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 11<br />

Regime 3—Semi-Constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

W R (SQ 2 )<br />

W L (SQ 2 )<br />

W L (SQ 1 )<br />

W R (SQ 1 )<br />

SQ1 SQ2 L SQ2L * R J1 SQ1L * SQ2R * J2 SQ1R *<br />

Regime 4—Semi-Constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

W L (SQ)<br />

W R (SQ)<br />

J 1 SQ L<br />

*<br />

J 2 L SQ R<br />

Figure 3. Context and the Separation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Powers</strong>. J=<strong>Court</strong> Median. SQ=Status<br />

Quo. L=Left Pivot. R=Right Pivot. SQ ∗ L =Left Pivot’s Indifference Po<strong>in</strong>t Vis-a-vis SQ.<br />

SQ ∗ R =Right Pivot’s Indifference Po<strong>in</strong>t Vis-a-vis SQ. W L(SQ) is the “preferred-to set” <strong>of</strong><br />

SQ for the Left Pivot. W R (SQ) is the “preferred-to set” <strong>of</strong> SQ for the Right Pivot.<br />

decision at L, the po<strong>in</strong>t on the legislative equilibrium that is closest to it and<br />

that avoids an override. L would, <strong>of</strong> course, block any override attempt by R<br />

which seeks to move policy back to the right. 13 Once aga<strong>in</strong>, while the <strong>Court</strong><br />

cannot set policy at J 1 , its ultimate decision at L is a net ga<strong>in</strong> for the <strong>Court</strong><br />

which, <strong>in</strong> turn, will lead it to grant review to the case.<br />

Indeed, this dynamic holds even when the <strong>Court</strong> falls with<strong>in</strong> the Left Pivot’s<br />

preferred-to set. Assume that <strong>Court</strong> personnel changes and J 2 becomes the<br />

new <strong>Court</strong> median. The <strong>Court</strong> still would be forced to render a decision at the<br />

Left Pivot’s ideal po<strong>in</strong>t. While a decision at J 2 would be better than the status<br />

quo for the Left Pivot, the Right Pivot would be worse <strong>of</strong>f. In response, the<br />

Right Pivot would propose override legislation either on or to the right <strong>of</strong> L,<br />

depend<strong>in</strong>g on where the <strong>Court</strong> set its policy. Anticipat<strong>in</strong>g this response, the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> would render a decision at L. This is the closest po<strong>in</strong>t on the legislative<br />

equilibrium that avoids an override. Nevertheless, because the <strong>Court</strong> can shift<br />

policy closer to its ideal po<strong>in</strong>t, it will grant review to the case.<br />

separation <strong>of</strong> powers models nevertheless argue that the <strong>Court</strong> will seek to avoid the override<br />

because <strong>of</strong> the legitimacy loss the <strong>Court</strong> would suffer from it. As stated above, however, some<br />

scholars argue that the <strong>Court</strong> will <strong>in</strong> fact seek an override <strong>in</strong> cases such as these (Spiller and Tiller,<br />

1996).<br />

13. Note that <strong>in</strong> Regime 4, the Left Pivot benefits from the <strong>Court</strong>’s decision. Without the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>’s <strong>in</strong>tervention, the status quo would be gridlocked—the pivots could not agree on a policy<br />

other than SQ. If, however, the <strong>Court</strong> gets <strong>in</strong>volved, it could shift policy to the Left Pivot’s<br />

ideal po<strong>in</strong>t.

12 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

Comb<strong>in</strong>ed, then, these four regimes and the strategic expectations derived<br />

therefrom lead to the follow<strong>in</strong>g hypothesis:<br />

Strategic SOP <strong>Agenda</strong>-<strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Hypothesis: If the location <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Left and Right Pivots, <strong>Court</strong> Median, and Status Quo lead to an<br />

Unconstra<strong>in</strong>ed or Semi-Constra<strong>in</strong>ed Regime, the <strong>Court</strong> will grant<br />

review to a case. Conversely, if the <strong>Court</strong> is <strong>in</strong> a Constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

Regime, it will deny review to a case.<br />

4.3 Who Are the Left and Right Pivots? Theories <strong>of</strong> Legislative Decision Mak<strong>in</strong>g<br />

Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g who the pivotal legislative actors are is a complicated task. Congressional<br />

scholars advocate equally plausible theories <strong>of</strong> congressional decision<br />

mak<strong>in</strong>g. Some scholars argue that legislation turns on the preferences <strong>of</strong><br />

the median legislator <strong>in</strong> each chamber. Other scholars argue that parties and<br />

committees exercise gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g control over legislation. Still other scholars<br />

contend that super-majority pivots largely dictate legislative outcomes. I rema<strong>in</strong><br />

neutral as to which is correct and therefore apply each <strong>of</strong> them.<br />

The chamber median model argues that legislative outcomes reflect the preferences<br />

<strong>of</strong> the median legislator <strong>in</strong> each chamber (Krehbiel, 1991, 1995). Accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to this model, members <strong>of</strong> Congress are elected with concrete preferences<br />

that drive their vot<strong>in</strong>g behavior and, as a result, the median member <strong>of</strong><br />

each chamber controls legislative outcomes (Lawrence, Maltzman and Smith,<br />

2006). That is, parties are simply the conglomeration <strong>of</strong> like-m<strong>in</strong>ded members<br />

who vote their preferences (K<strong>in</strong>gdon, 1973). Thus, the Left Pivot under the<br />

Chamber Median model is the most liberal among the House chamber median,<br />

the Senate chamber median, and the president. The Right Pivot is the most<br />

conservative among the House chamber median, the Senate chamber median,<br />

and the president.<br />

The party gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g model argues that majority party leaders control vot<strong>in</strong>g<br />

procedures to channel outcomes that are preferred by party members (Cox<br />

and McCubb<strong>in</strong>s, 2005). To facilitate legislative outcomes that aid their electoral<br />

chances, legislators create party leadership, whose function is to solve<br />

coord<strong>in</strong>ation problems among party members and pass laws that reflect the<br />

“brand name” desired by the majority party’s median member. Under this theory,<br />

party leadership will only allow legislation to receive an up or down vote<br />

if it will satisfy both the chamber and party medians. That is, the party will<br />

only br<strong>in</strong>g legislation to a floor vote when party leaders expect to w<strong>in</strong>. As<br />

Lawrence, Maltzman and Smith (2006) state: “[T]he majority party manipulates<br />

the amendment agenda so as to restrict the chamber median’s ability to<br />

move outcomes towards that legislator’s preferred po<strong>in</strong>t and away from the majority<br />

party median’s ideal po<strong>in</strong>t” (41). In the end, the majority party obta<strong>in</strong>s<br />

the outcome it wants while still allow<strong>in</strong>g legislators to vote their s<strong>in</strong>cere preferences<br />

on f<strong>in</strong>al passage votes (Lawrence, Maltzman and Smith, 2006, 41). 14<br />

14. The majority party can allow members to vote s<strong>in</strong>cerely on f<strong>in</strong>al passage votes, then, be-

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 13<br />

Under the party gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g model, then, the Left Pivot is the most liberal actor<br />

among the majority party medians <strong>in</strong> each chamber, the chamber medians,<br />

and the president. The Right Pivot is the most conservative among the majority<br />

party medians <strong>in</strong> each chamber, the chamber medians, and the president. 15<br />

The committee gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g model argues that legislative outcomes are largely<br />

a function <strong>of</strong> committee preferences (Shepsle and We<strong>in</strong>gast, 1987). When a<br />

member proposes a bill, the chamber’s presid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>ficer refers that bill to the<br />

committee with jurisdiction over the subject matter. For the bill to proceed,<br />

the committee must report it to the floor. Committees thus possess negative<br />

agenda control. That is, they have “the ability to successfully defend the status<br />

quo <strong>in</strong> the face <strong>of</strong> a parent-chamber majority <strong>in</strong> favor <strong>of</strong> change. . . ” (Smith,<br />

1989, 171). Committees will keep the gates closed when the policy they expect<br />

the chamber median to make is worse for them than is the status quo. That<br />

is, once the committee reports the bill to the full chamber, an open rule allows<br />

the chamber to amend it down to the median member’s ideal po<strong>in</strong>t; the result<br />

is a bill with the policy location <strong>of</strong> the parent chamber median. Accord<strong>in</strong>gly,<br />

if the committee median is closer to the status quo than to its parent chamber<br />

median, s/he will bottle up the legislation <strong>in</strong> committee. It is only when the<br />

committee median is closer to the parent chamber median than to the status<br />

quo that s/he will open the gates. Thus, the Left Pivot under the committee<br />

gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g model is the most liberal among the Judiciary Committee medians,<br />

the chamber medians, each Judiciary Committee Median’s <strong>in</strong>difference<br />

po<strong>in</strong>t vis-a-vis its parent chamber median, and the president. The Right Pivot<br />

is the most conservative among the Judiciary Committee medians, the chamber<br />

medians, each Judiciary Committee Median’s <strong>in</strong>difference po<strong>in</strong>t vis-a-vis<br />

its parent chamber median, and the president.<br />

F<strong>in</strong>ally, the veto-filibuster model argues that the veto and filibuster pivots<br />

may control legislative outcomes. The presidential veto and senate filibuster<br />

are potential obstacles to the legislative process that any successful legislation<br />

may need to overcome (Krehbiel, 1998; Primo, B<strong>in</strong>der and Maltzman, 2008).<br />

Legislative overrides <strong>of</strong> presidential vetoes require the consent <strong>of</strong> two-thirds <strong>of</strong><br />

both houses. Additionally, <strong>in</strong>dividual senators may filibuster legislation until<br />

stopped via cloture, which requires the consent <strong>of</strong> 60 senators. 16 Because these<br />

pivots are important actors to assuage, policy change typically requires large,<br />

bipartisan coalitions (Krehbiel, 1998). The relevant pivots under this model<br />

depend on political circumstances. For Democratic presidents, the left pivot<br />

is the most liberal <strong>of</strong> the 146th Representative, the 34th Senator, the House<br />

and Senate medians, while the right pivot is the 60th Senator. For Republican<br />

cause it has already siphoned out the cases <strong>in</strong> which s<strong>in</strong>cere votes would make the party worse<br />

<strong>of</strong>f.<br />

15. There is considerable disagreement among congressional scholars as to whether the majority<br />

party <strong>in</strong> the Senate possesses the same negative agenda control as the House majority party<br />

(Cox and McCubb<strong>in</strong>s, 2005; Smith, 2007). This debate is irrelevant to my study, as the Senate<br />

majority party median was never the leftmost or rightmost pivot.<br />

16. In 1975, the Senate lowered the number <strong>of</strong> votes needed to <strong>in</strong>voke cloture from 2 3 to 3 5 .<br />

Prior to that change, the filibuster pivots were the 34th Senator and the 67th Senator.

14 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

presidents, the left pivot is the 40th Senator while the right pivot is the most<br />

conservative among the chamber medians, the 290th representative, and the<br />

67th senator.<br />

5. Data and Methods<br />

To test my hypothesis, I exam<strong>in</strong>ed 430 paid certiorari petitions and appeals<br />

that made the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong>’s discuss list 17 between the 1953-1993 terms <strong>in</strong><br />

which the petitioner requested the <strong>Court</strong> either to engage <strong>in</strong> statutory <strong>in</strong>terpretation<br />

over a federal statute or to exercise judicial review by strik<strong>in</strong>g one<br />

down. 18 My tests <strong>of</strong> strategic behavior require three sources <strong>of</strong> data—a measure<br />

<strong>of</strong> the status quo, a measure <strong>of</strong> each pivotal actor’s preferences, and a<br />

source to code the relevant factors present at the agenda stage.<br />

To determ<strong>in</strong>e the status quo <strong>in</strong> each case, I read the “Questions Presented”<br />

<strong>in</strong> over three thousand cert petitions and appeals. 19 If the petitioner requested<br />

the <strong>Court</strong> to <strong>in</strong>terpret a federal statute or exercise judicial review over it, I <strong>in</strong>cluded<br />

the petition (or appeal) <strong>in</strong> my sample. If not, I excluded the petition<br />

from the sample. To mitigate aga<strong>in</strong>st the threat <strong>of</strong> multiple issues <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong><br />

a case, I <strong>in</strong>cluded only those petitions or appeals <strong>in</strong> which the petitioners <strong>in</strong>voked<br />

one primary statute or subsection there<strong>of</strong>. For example, the petition <strong>in</strong><br />

California v. Zolnay (75-1354) raised the follow<strong>in</strong>g questions: “(1) Whether<br />

any question may be asked <strong>of</strong> suspects after one <strong>of</strong> the suspects has <strong>in</strong>quired<br />

about his right to counsel under Miranda?; and (2) Whether a suspect may<br />

<strong>in</strong>voke the right to counsel under Miranda for another suspect aga<strong>in</strong>st the second<br />

suspect’s wishes?” Because these questions failed to turn on a federal<br />

statute, I excluded the petition from my sample. On the other hand, Mobay<br />

Chemical Corporation v. Costle (78-308) <strong>in</strong>voked one precise federal statute<br />

and therefore was <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the sample. The Question Presented <strong>in</strong> Mobay<br />

was “Whether Section (3)(c)(1)(D) <strong>of</strong> the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and<br />

Rodenticide Act. . . violates the due process and just compensation clauses <strong>of</strong><br />

17. I obta<strong>in</strong>ed the <strong>Court</strong>’s discuss lists from the papers <strong>of</strong> former Justices Blackmun, Brennan,<br />

Burton, Warren, and Douglas. Note that the “discuss list” came about <strong>in</strong> the early 1970s. Previous<br />

to the discuss list, justices relied on the “special list.” All cases were deemed worthy <strong>of</strong> review<br />

unless put on the special list. Special list cases were summarily denied review. Thus, when I state<br />

that I analyze all cases that made the discuss list over this time period, I mean simply that I analyze<br />

all cases the <strong>Court</strong> discussed at conference.<br />

One potential concern is that by sampl<strong>in</strong>g from the discuss list, my data suffer from selection<br />

bias—that strategic justices may refuse to put a case on the discuss list if they expect Congress to<br />

override the <strong>Court</strong>’s decision. This concern is unwarranted. First, numerous justices have stated<br />

that nearly all petitions <strong>of</strong>f the list are frivolous (Brennan, 1973; G<strong>in</strong>sburg, 1994, 479). There is<br />

little reason to expect the <strong>Court</strong> to strategically deny review based on the separation <strong>of</strong> powers <strong>in</strong><br />

such cases. Second, it takes only one justice to place a case on the discuss list. While one justice<br />

might strategically refra<strong>in</strong> from putt<strong>in</strong>g a case on the discuss list, others are likely to be able to<br />

vote s<strong>in</strong>cerely and, thus, put the case on.<br />

18. I analyze cases deal<strong>in</strong>g with federal statutes because Congress is most likely to care about<br />

them, hav<strong>in</strong>g already once overcome its collective action problems to pass the legislation.<br />

19. The Questions Presented expla<strong>in</strong> which precise subsection the petitioner has <strong>in</strong>voked for<br />

review. When the Questions Presented was not clear on the subsection, I looked to the “Constitutional<br />

and Statutory Provisions Involved” section, which <strong>of</strong>ten quotes the ma<strong>in</strong> statute at issue.

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 15<br />

the Fifth Amendment. . . ” Because this question <strong>in</strong>vokes a clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed federal<br />

statutory provision, I <strong>in</strong>cluded it <strong>in</strong> my sample. After review<strong>in</strong>g roughly<br />

3,000 paid cert petitions and appeals, I reta<strong>in</strong>ed 863 usable observations.<br />

Once I determ<strong>in</strong>ed the statute (or subsection there<strong>of</strong>) at issue <strong>in</strong> the case,<br />

I analyzed its legislative history to determ<strong>in</strong>e the bill that created the law. I<br />

then entered each bill number <strong>in</strong>to Poole and Rosenthal’s “Vote View” s<strong>of</strong>tware<br />

to determ<strong>in</strong>e (1) whether there was a recorded vote on the bill and, (2)<br />

if so, what the roll call number <strong>of</strong> that vote was. 20 Bills that passed via voice<br />

vote were excluded from the analysis, as were bills passed unanimously, s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

there is no usable roll call data to determ<strong>in</strong>e their policy <strong>in</strong> common space.<br />

In total, out <strong>of</strong> the 863 petitions and appeals <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g a federal statute, I was<br />

able to reta<strong>in</strong> 430 observations with usable roll call data. I then located the relevant<br />

DW-NOMINATE roll call coord<strong>in</strong>ates for each recorded bill and l<strong>in</strong>early<br />

transformed those coord<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong>to Common Space (Sala and Spriggs, 2004). 21<br />

This gave me a measurement <strong>of</strong> the status quo <strong>in</strong> the same policy space as the<br />

ideal po<strong>in</strong>ts <strong>of</strong> justices’ and legislators. 22<br />

To code the pivotal actors’ preferences, I relied on Poole and Rosenthal’s<br />

Common Space data and the Judicial Common Space data (Poole and Rosenthal,<br />

1997; Epste<strong>in</strong> et al., 2007). These data place actors <strong>in</strong> the same ideological<br />

space and provide measures <strong>of</strong> actors’ policy preferences that are directly<br />

comparable across <strong>in</strong>stitutions (i.e. between Congress and the <strong>Court</strong>) and over<br />

time. 23 By cod<strong>in</strong>g the status quo as discussed above, I can directly compare the<br />

status quo (the statute) with the policy location <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> and the<br />

legislative pivots.<br />

My key <strong>in</strong>dependent variable <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest is Constra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>Court</strong>, which takes<br />

on a value <strong>of</strong> 1 whenever the separation <strong>of</strong> powers precludes the <strong>Court</strong> from<br />

shift<strong>in</strong>g policy closer to it. That is, <strong>in</strong> Regime 2 (and its mirror), Constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

<strong>Court</strong> takes on a value <strong>of</strong> 1. In Regimes 1, 3, and 4 (and their mirrors), Constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

<strong>Court</strong> takes on a value <strong>of</strong> 0.<br />

In addition to my key covariate <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terest, I control for a host <strong>of</strong> additional<br />

factors that might lead the <strong>Court</strong> to grant or deny review to a case. My source<br />

for these data are the prelim<strong>in</strong>ary cert pool memos written <strong>in</strong> each case which I<br />

20. If the bill went to conference and both chambers recorded a vote on the conference report, I<br />

coded SQ as the average common space score between the two chambers. When only one chamber<br />

recorded a vote on the conference report, I coded SQ as the common space score retrieved for it.<br />

S<strong>in</strong>ce both chambers are vot<strong>in</strong>g on the exact same bill (the conference report), the cutpo<strong>in</strong>ts for<br />

the two chambers theoretically should be identical. If there was no conference report (i.e. the f<strong>in</strong>al<br />

passage vote was the last vote), I looked to see if there was a recoded f<strong>in</strong>al passage vote on the<br />

bill. If so, I coded SQ as the average <strong>of</strong> the f<strong>in</strong>al passage votes for both chambers. If there was a<br />

recorded f<strong>in</strong>al passage vote <strong>in</strong> only one chamber, I coded SQ with that score.<br />

21. To do so, I regressed each member’s DW-NOMINATE scores for the Congress <strong>in</strong> which the<br />

roll call vote was held. I then used the parameters estimated from this model to l<strong>in</strong>early transform<br />

the DW-NOMINATE coord<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong>to Common Space (Sala and Spriggs, 2004, 202).<br />

22. As I discuss <strong>in</strong> the Results section below, I also measured the status quo by cod<strong>in</strong>g the<br />

Judicial Common Space (Epste<strong>in</strong> et al., 2007) <strong>of</strong> the judges from the lower federal court that heard<br />

the case.<br />

23. Bailey (2007) is an alternative.

16 The Journal <strong>of</strong> Law, Economics, & Organization. V0 N0<br />

obta<strong>in</strong>ed by travel<strong>in</strong>g to the Library <strong>of</strong> Congress and search<strong>in</strong>g through the papers<br />

<strong>of</strong> former Justices Blackmun, Brennan, Burton, Douglas, and Warren. 24<br />

These data span the 1953-1985 <strong>Court</strong> terms. My source for the 1986-1993<br />

terms come from Epste<strong>in</strong>, Segal and Spaeth (2007). To control for the political<br />

salience <strong>of</strong> the case, I exam<strong>in</strong>ed the activity <strong>of</strong> organized <strong>in</strong>terests at the<br />

<strong>Court</strong>’s agenda stage. That is, Amici is a count <strong>of</strong> the total number <strong>of</strong> amicus<br />

curiae briefs filed both <strong>in</strong> support <strong>of</strong> and <strong>in</strong> opposition to the petition for certiorari<br />

(Caldeira and Wright, 1988). Dissent Below takes on a value <strong>of</strong> 1 if the<br />

pool memo <strong>in</strong> the case notes a dissent <strong>in</strong> the court below; 0 otherwise. Reverse<br />

Below equals 1 if the <strong>in</strong>termediate court reversed the trial court; 0 otherwise.<br />

Additionally, I code Conflict Below as 1 if the cert pool writer noted a conflict<br />

<strong>in</strong> the lower courts over the correct <strong>in</strong>terpretation and/or application <strong>of</strong> federal<br />

law; 0 otherwise. I also controlled for the position <strong>of</strong> the Solicitor General. If<br />

the SG requests review be granted (either as petitioner or as an amici advocat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the grant <strong>of</strong> review), US Support takes on a value <strong>of</strong> 1; 0 otherwise. If<br />

the SG was respondent or filed an amicus brief oppos<strong>in</strong>g review, US Oppose<br />

takes on a value <strong>of</strong> 1; 0 otherwise. 25 F<strong>in</strong>ally, I exam<strong>in</strong>e whether the lower court<br />

struck down the federal statute at issue. If so, Lower <strong>Court</strong> Strike takes on a<br />

value <strong>of</strong> 1; 0 otherwise.<br />

6. Results<br />

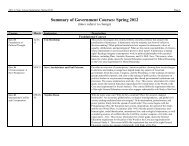

Figure 4 presents the results <strong>of</strong> the SOP model for each theory <strong>of</strong> legislative<br />

decision mak<strong>in</strong>g. The solid circles are the parameter estimates and the horizontal<br />

l<strong>in</strong>es represent the 95 percent confidence <strong>in</strong>tervals for those estimates based<br />

on robust standard errors. As Figure 4 shows, the coefficient on Constra<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

<strong>Court</strong> <strong>in</strong> every model <strong>of</strong> legislative decision mak<strong>in</strong>g is not statistically significant.<br />

Take first the Chamber Median model. This model argued that when the<br />

<strong>Court</strong> was more liberal than the status quo, the House and Senate chamber<br />

medians, and the president, it would strategically decl<strong>in</strong>e to review the case.<br />

The results, however, do not support such an <strong>in</strong>ference. While the coefficient<br />

on Constra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>Court</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Chamber Median model is negative, it does not<br />

approach conventional levels <strong>of</strong> statistical significance. That is, regardless <strong>of</strong><br />

the ideological location <strong>of</strong> the status quo <strong>in</strong> relation to the House, Senate, and<br />

President, the <strong>Court</strong> grants review, even while controll<strong>in</strong>g for the factors most<br />

commonly associated with review. What is more, <strong>in</strong> the Party Gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g<br />

model, Committee Gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g model, and Filibuster-Veto model, the coefficient<br />

(while not statistically significant) is signed <strong>in</strong> the positive direction. In<br />

short, the <strong>Court</strong> granted review to cases without regard to how a shift <strong>in</strong> the status<br />

quo would effect Congress and the president–and it did so <strong>in</strong> every model<br />

24. For terms prior to the adoption <strong>of</strong> the cert pool, I read through the cert memos written by<br />

Justices Burton’s and Douglas’s law clerks.<br />

25. The <strong>Court</strong> sometimes calls for the views <strong>of</strong> the Solicitor General at which po<strong>in</strong>t the SG’s<br />

<strong>of</strong>fice essentially is forced to make a recommendation <strong>in</strong> the case (Black and Owens, 2008). Controll<strong>in</strong>g<br />

for <strong>in</strong>vitations does not change my results.

®<br />

<strong>Supreme</strong> <strong>Court</strong> <strong>Agenda</strong> <strong>Sett<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> a <strong>System</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Shared</strong> <strong>Powers</strong> 17<br />

Vulnerable <strong>Court</strong><br />

Amici<br />

Dissent Below<br />

Reverse Below<br />

Conflict Below<br />

US Supports<br />

US Opposes<br />

Lower <strong>Court</strong> Strike<br />

−.5 0 .5 1 1.5 2<br />

Chamber Median Model<br />

Vulnerable <strong>Court</strong><br />

Amici<br />

Dissent Below<br />

Reverse Below<br />

Conflict Below<br />

US Supports<br />

US Opposes<br />

Lower <strong>Court</strong> Strike<br />

−1 −.5 0 .5 1 1.5 2 2.5<br />

Party Gatekeep<strong>in</strong>g Model<br />

Vulnerable <strong>Court</strong><br />