Financing Education / pdf - Unesco

Financing Education / pdf - Unesco

Financing Education / pdf - Unesco

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PROGRESS IN FINANCING EDUCATION FOR ALL<br />

Changing national financial commitments to EFA since Dakar<br />

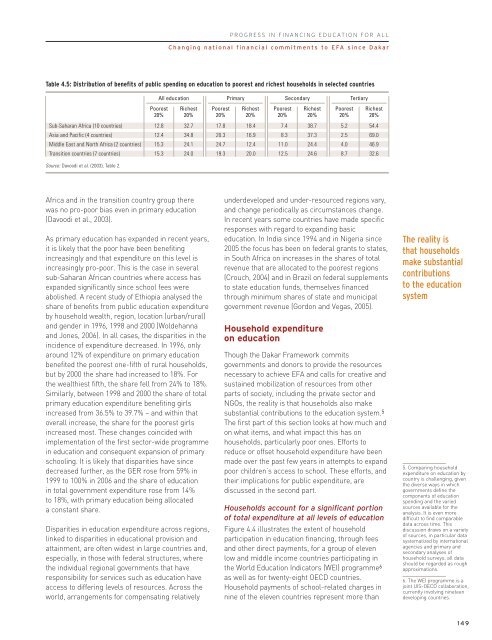

Table 4.5: Distribution of benefits of public spending on education to poorest and richest households in selected countries<br />

All education Primary Secondary Tertiary<br />

Sub-Saharan Africa (10 countries)<br />

Asia and Pacific (4 countries)<br />

Middle East and North Africa (2 countries)<br />

Transition countries (7 countries)<br />

Poorest<br />

20%<br />

Richest<br />

20%<br />

Poorest<br />

20%<br />

Richest<br />

20%<br />

Poorest<br />

20%<br />

Richest<br />

20%<br />

Poorest<br />

20%<br />

Richest<br />

20%<br />

12.8 32.7 17.8 18.4 7.4 38.7 5.2 54.4<br />

12.4 34.8 20.3 16.9 8.3 37.3 2.5 69.0<br />

15.3 24.1 24.7 12.4 11.0 24.4 4.0 46.9<br />

15.3 24.0 19.3 20.0 12.5 24.6 8.7 32.6<br />

Source: Davoodi et al. (2003), Table 2.<br />

Africa and in the transition country group there<br />

was no pro-poor bias even in primary education<br />

(Davoodi et al., 2003).<br />

As primary education has expanded in recent years,<br />

it is likely that the poor have been benefiting<br />

increasingly and that expenditure on this level is<br />

increasingly pro-poor. This is the case in several<br />

sub-Saharan African countries where access has<br />

expanded significantly since school fees were<br />

abolished. A recent study of Ethiopia analysed the<br />

share of benefits from public education expenditure<br />

by household wealth, region, location (urban/rural)<br />

and gender in 1996, 1998 and 2000 (Woldehanna<br />

and Jones, 2006). In all cases, the disparities in the<br />

incidence of expenditure decreased. In 1996, only<br />

around 12% of expenditure on primary education<br />

benefited the poorest one-fifth of rural households,<br />

but by 2000 the share had increased to 18%. For<br />

the wealthiest fifth, the share fell from 24% to 18%.<br />

Similarly, between 1998 and 2000 the share of total<br />

primary education expenditure benefiting girls<br />

increased from 36.5% to 39.7% – and within that<br />

overall increase, the share for the poorest girls<br />

increased most. These changes coincided with<br />

implementation of the first sector-wide programme<br />

in education and consequent expansion of primary<br />

schooling. It is likely that disparities have since<br />

decreased further, as the GER rose from 59% in<br />

1999 to 100% in 2006 and the share of education<br />

in total government expenditure rose from 14%<br />

to 18%, with primary education being allocated<br />

a constant share.<br />

Disparities in education expenditure across regions,<br />

linked to disparities in educational provision and<br />

attainment, are often widest in large countries and,<br />

especially, in those with federal structures, where<br />

the individual regional governments that have<br />

responsibility for services such as education have<br />

access to differing levels of resources. Across the<br />

world, arrangements for compensating relatively<br />

underdeveloped and under-resourced regions vary,<br />

and change periodically as circumstances change.<br />

In recent years some countries have made specific<br />

responses with regard to expanding basic<br />

education. In India since 1994 and in Nigeria since<br />

2005 the focus has been on federal grants to states,<br />

in South Africa on increases in the shares of total<br />

revenue that are allocated to the poorest regions<br />

(Crouch, 2004) and in Brazil on federal supplements<br />

to state education funds, themselves financed<br />

through minimum shares of state and municipal<br />

government revenue (Gordon and Vegas, 2005).<br />

Household expenditure<br />

on education<br />

Though the Dakar Framework commits<br />

governments and donors to provide the resources<br />

necessary to achieve EFA and calls for creative and<br />

sustained mobilization of resources from other<br />

parts of society, including the private sector and<br />

NGOs, the reality is that households also make<br />

substantial contributions to the education system. 5<br />

The first part of this section looks at how much and<br />

on what items, and what impact this has on<br />

households, particularly poor ones. Efforts to<br />

reduce or offset household expenditure have been<br />

made over the past few years in attempts to expand<br />

poor children’s access to school. These efforts, and<br />

their implications for public expenditure, are<br />

discussed in the second part.<br />

Households account for a significant portion<br />

of total expenditure at all levels of education<br />

Figure 4.4 illustrates the extent of household<br />

participation in education financing, through fees<br />

and other direct payments, for a group of eleven<br />

low and middle income countries participating in<br />

the World <strong>Education</strong> Indicators (WEI) programme 6<br />

as well as for twenty-eight OECD countries.<br />

Household payments of school-related charges in<br />

nine of the eleven countries represent more than<br />

The reality is<br />

that households<br />

make substantial<br />

contributions<br />

to the education<br />

system<br />

5. Comparing household<br />

expenditure on education by<br />

country is challenging, given<br />

the diverse ways in which<br />

governments define the<br />

components of education<br />

spending and the varied<br />

sources available for the<br />

analysis. It is even more<br />

difficult to find comparable<br />

data across time. This<br />

discussion draws on a variety<br />

of sources, in particular data<br />

systematized by international<br />

agencies and primary and<br />

secondary analyses of<br />

household surveys; all data<br />

should be regarded as rough<br />

approximations.<br />

6. The WEI programme is a<br />

joint UIS-OECD collaboration,<br />

currently involving nineteen<br />

developing countries.<br />

149