Financing Education / pdf - Unesco

Financing Education / pdf - Unesco

Financing Education / pdf - Unesco

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

0<br />

0<br />

8<br />

CHAPTER 4<br />

2<br />

<strong>Education</strong> for All Global Monitoring Report<br />

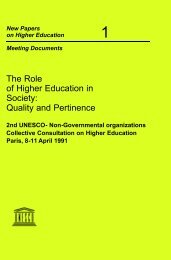

Figure 4.13: Breakdown of aid commitments to education by level,<br />

2004 and 2005 average<br />

France<br />

IDA<br />

Japan<br />

Germany<br />

United States<br />

EC<br />

United Kingdom<br />

Netherlands<br />

AsDF<br />

Canada<br />

Norway<br />

Spain<br />

Basic<br />

Belgium<br />

Australia<br />

Secondary<br />

Denmark<br />

Sweden<br />

Post-secondary<br />

AfDF<br />

Austria<br />

Unspecified<br />

UNICEF<br />

Finland<br />

Portugal<br />

Ireland<br />

New Zealand<br />

FTI<br />

Italy<br />

IDB Spec. Fund<br />

Greece<br />

Switzerland<br />

Luxembourg<br />

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5<br />

Constant 2005 US$ billions<br />

Notes: Only direct aid to education is broken down by level.<br />

AfDF = African Development Fund; AsDF = Asian Development Fund; EC = European Commission; FTI = Fast Track<br />

Initiative Catalytic Fund; IDA = International Development Association; IDB = Inter-American Development Bank<br />

(Special Fund).<br />

Source: OECD-DAC (2007c).<br />

13. The increase may be<br />

overstated to the extent<br />

that the definition of<br />

poverty-reducing<br />

expenditure can become<br />

more comprehensive<br />

within a country over time.<br />

It may also vary from one<br />

country to another.<br />

of finance for education in Latin America and the<br />

Caribbean (Box 4.3). The second additional source<br />

is countries outside the twenty-two OECD-DAC<br />

members, and private foundations. Sixteen non-<br />

DAC countries report aid activities to the DAC<br />

Secretariat. Of these, only the Czech Republic,<br />

the Republic of Korea and Turkey report aid for<br />

education. Most goes for scholarships in tertiary<br />

education, with very little for basic education.<br />

Other sources of aid for education are the Islamic<br />

Development Bank and the Gulf Cooperation<br />

Council. At a meeting of bilateral and multilateral<br />

donors in November 2006, these two institutions<br />

pledged US$109 million for education in Yemen,<br />

out of a total of US$307 million pledged<br />

(Government of Yemen, 2007). China has recently<br />

emerged as a potential source of external finance<br />

for African countries. However, the focus of the<br />

US$5 billion China-Africa Development Fund is<br />

on natural resources, infrastructure, large-scale<br />

agriculture, manufacturing and industrial parks.<br />

Few, if any, of the funds are likely to be directed<br />

to basic education.<br />

In addition to governments, some private<br />

foundations are becoming active in basic education<br />

in developing countries. In May 2007, the Soros<br />

Foundation pledged US$5 million for Liberia if a<br />

matching pledge could be found, and the Gates<br />

and Hewlett Foundations have committed<br />

US$60 million over three years for programmes<br />

aimed at improving learning achievements in lowincome<br />

countries. The largest initiative reported so<br />

far is the US$10 billion endowment of a foundation<br />

to raise educational standards and literacy in the<br />

Middle East, announced by the ruler of Dubai at<br />

the World Economic Forum in Jordan in June 2007<br />

(The Guardian, 2007).<br />

Debt relief moves up the list of priorities<br />

The Dakar Framework for Action argued that<br />

higher priority should be given to debt relief linked<br />

to expenditure on poverty reduction programmes<br />

having a strong commitment to basic education.<br />

While the recent debt relief programmes have<br />

benefited only a subset of the world’s low-income<br />

countries, for those that have benefited the<br />

programmes have been among the most effective<br />

international initiatives to increase government<br />

resources.<br />

The introduction of the Enhanced HIPC Initiative<br />

for debt relief in 1999, which expanded the previous<br />

programme begun in 1996, required countries<br />

to prepare and implement a poverty reduction<br />

strategy as a condition for qualification. Thirty<br />

countries have since qualified for relief – twentyfive<br />

in sub-Saharan Africa, four in Central America<br />

and the Caribbean, and one in South America –<br />

and a further ten are eligible. All are least<br />

developed countries. On average, the ratio of debt<br />

service to GDP in these countries fell from 3.6%<br />

to 2.2% between 1999 and 2005, and the ratio<br />

of debt service to government revenue fell from<br />

23.5% to 11.7%, allowing governments to increase<br />

expenditure on domestic programmes (IDA/IMF,<br />

2006). Part of the HIPC process is monitoring<br />

spending on poverty-reducing measures. Across<br />

the thirty countries, expenditure on such activities,<br />

in which education is always central, increased on<br />

average between 1999 and 2005 from 6.4% to 8.5%<br />

of GDP and from 40.9% to 46.1% of total<br />

government expenditure. 13 The absolute increase<br />

in poverty-reducing expenditure was far larger<br />

than the decline in debt service payments. This<br />

suggests that governments have used not only<br />

funds freed by debt relief for their poverty<br />

reduction programmes, but also other resources.<br />

162