Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism - Covidien

Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism - Covidien

Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism - Covidien

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

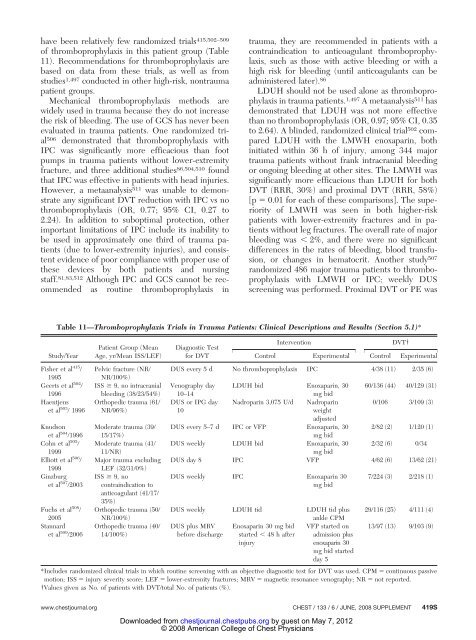

have been relatively few randomized trials 415,502–509<br />

<strong>of</strong> thromboprophylaxis in this patient group (Table<br />

11). Recommendations for thromboprophylaxis are<br />

based on data from these trials, as well as from<br />

studies 1,497 conducted in other high-risk, nontrauma<br />

patient groups.<br />

Mechanical thromboprophylaxis methods are<br />

widely used in trauma because they do not increase<br />

the risk <strong>of</strong> bleeding. The use <strong>of</strong> GCS has never been<br />

evaluated in trauma patients. One randomized trial<br />

506 demonstrated that thromboprophylaxis with<br />

IPC was significantly more efficacious than foot<br />

pumps in trauma patients without lower-extremity<br />

fracture, and three additional studies 86,504,510 found<br />

that IPC was effective in patients with head injuries.<br />

However, a metaanalysis 511 was unable to demonstrate<br />

any significant DVT reduction with IPC vs no<br />

thromboprophylaxis (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.27 to<br />

2.24). In addition to suboptimal protection, other<br />

important limitations <strong>of</strong> IPC include its inability to<br />

be used in approximately one third <strong>of</strong> trauma patients<br />

(due to lower-extremity injuries), and consistent<br />

evidence <strong>of</strong> poor compliance with proper use <strong>of</strong><br />

these devices by both patients and nursing<br />

staff. 81,83,512 Although IPC and GCS cannot be recommended<br />

as routine thromboprophylaxis in<br />

trauma, they are recommended in patients with a<br />

contraindication to anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis,<br />

such as those with active bleeding or with a<br />

high risk for bleeding (until anticoagulants can be<br />

administered later). 86<br />

LDUH should not be used alone as thromboprophylaxis<br />

in trauma patients. 1,497 A metaanalysis 511 has<br />

demonstrated that LDUH was not more effective<br />

than no thromboprophylaxis (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.35<br />

to 2.64). A blinded, randomized clinical trial 502 compared<br />

LDUH with the LMWH enoxaparin, both<br />

initiated within 36 h <strong>of</strong> injury, among 344 major<br />

trauma patients without frank intracranial bleeding<br />

or ongoing bleeding at other sites. The LMWH was<br />

significantly more efficacious than LDUH for both<br />

DVT (RRR, 30%) and proximal DVT (RRR, 58%)<br />

[p � 0.01 for each <strong>of</strong> these comparisons]. The superiority<br />

<strong>of</strong> LMWH was seen in both higher-risk<br />

patients with lower-extremity fractures and in patients<br />

without leg fractures. The overall rate <strong>of</strong> major<br />

bleeding was � 2%, and there were no significant<br />

differences in the rates <strong>of</strong> bleeding, blood transfusion,<br />

or changes in hematocrit. Another study 507<br />

randomized 486 major trauma patients to thromboprophylaxis<br />

with LMWH or IPC; weekly DUS<br />

screening was performed. Proximal DVT or PE was<br />

Table 11—Thromboprophylaxis Trials in Trauma Patients: Clinical Descriptions and Results (Section 5.1)*<br />

Study/Year<br />

Fisher et al 415 /<br />

1995<br />

Geerts et al 502 /<br />

1996<br />

Haentjens<br />

et al 503 / 1996<br />

Knudson<br />

et al 504 /1996<br />

Cohn et al 505 /<br />

1999<br />

Elliott et al 506 /<br />

1999<br />

Ginzburg<br />

et al 507 /2003<br />

Fuchs et al 508 /<br />

2005<br />

Stannard<br />

et al 509 /2006<br />

Patient Group (Mean<br />

Age, yr/Mean ISS/LEF)<br />

Pelvic fracture (NR/<br />

NR/100%)<br />

ISS � 9, no intracranial<br />

bleeding (38/23/54%)<br />

Orthopedic trauma (61/<br />

NR/96%)<br />

Moderate trauma (39/<br />

15/17%)<br />

Moderate trauma (41/<br />

11/NR)<br />

Major trauma excluding<br />

LEF (32/31/0%)<br />

ISS � 9, no<br />

contraindication to<br />

anticoagulant (41/17/<br />

35%)<br />

Orthopedic trauma (50/<br />

NR/100%)<br />

Orthopedic trauma (40/<br />

14/100%)<br />

Diagnostic Test<br />

for DVT<br />

Intervention DVT†<br />

Control Experimental Control Experimental<br />

DUS every 5 d No thromboprophylaxis IPC 4/38 (11) 2/35 (6)<br />

Venography day LDUH bid Enoxaparin, 30 60/136 (44) 40/129 (31)<br />

10–14<br />

mg bid<br />

DUS or IPG day Nadroparin 3,075 U/d Nadroparin<br />

0/106 3/109 (3)<br />

10<br />

weight<br />

adjusted<br />

DUS every 5–7 d IPC or VFP Enoxaparin, 30<br />

mg bid<br />

2/82 (2) 1/120 (1)<br />

DUS weekly LDUH bid Enoxaparin, 30<br />

mg bid<br />

2/32 (6) 0/34<br />

DUS day 8 IPC VFP 4/62 (6) 13/62 (21)<br />

DUS weekly IPC Enoxaparin 30<br />

mg bid<br />

DUS weekly LDUH tid LDUH tid plus<br />

ankle CPM<br />

DUS plus MRV Enoxaparin 30 mg bid VFP started on<br />

before discharge started � 48 h after admission plus<br />

injury<br />

enoxaparin 30<br />

mg bid started<br />

day 5<br />

7/224 (3) 2/218 (1)<br />

29/116 (25) 4/111 (4)<br />

13/97 (13) 9/103 (9)<br />

*Includes randomized clinical trials in which routine screening with an objective diagnostic test for DVT was used. CPM � continuous passive<br />

motion; ISS � injury severity score; LEF � lower-extremity fractures; MRV � magnetic resonance venography; NR � not reported.<br />

†Values given as No. <strong>of</strong> patients with DVT/total No. <strong>of</strong> patients (%).<br />

www.chestjournal.org CHEST / 133 /6/JUNE, 2008 SUPPLEMENT 419S<br />

Downloaded from<br />

chestjournal.chestpubs.org by guest on May 7, 2012<br />

© 2008 American College <strong>of</strong> Chest Physicians