Public Lighting Strategy 2013 - City of Melbourne

Public Lighting Strategy 2013 - City of Melbourne

Public Lighting Strategy 2013 - City of Melbourne

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Page 1 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

F U T U R E M E L B O U R N E ( E N V I R O N M E N T )<br />

C O M M I T T E E R E P O R T<br />

Agenda Item 6.4<br />

PUBLIC LIGHTING STRATEGY <strong>2013</strong> 6 August <strong>2013</strong><br />

Presenter: Ge<strong>of</strong>f Robinson, Manager Engineering Services<br />

Purpose and background<br />

1. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this report is to seek approval <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> (PLS).<br />

2. The Future <strong>Melbourne</strong> Committee at its meeting on 9 April <strong>2013</strong> endorsed that the draft <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong><br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> be released for public consultation for the period from 9 April to 8 May <strong>2013</strong>.<br />

Key issues<br />

3. The feedback from public consultation (see Attachment 2) was evaluated by an internal reference group<br />

and has been incorporated into the PLS proposed for approval (see Attachment 3).<br />

4. The aims <strong>of</strong> the community engagement process were to:<br />

4.1. Ensure the contribution multidisciplinary perspectives and expertise from relevant areas <strong>of</strong> Council<br />

to assist with planning and implementation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong>.<br />

4.2. Provide the community and stakeholders with accessible information about public lighting<br />

infrastructure, and receive their feedback on the <strong>Strategy</strong>.<br />

4.3. Capture the expertise and ideas <strong>of</strong> the community and organisations affected by public lighting in<br />

the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>.<br />

4.4. Capture the expertise and ideas <strong>of</strong> other <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> residents and visitors about public<br />

lighting.<br />

5. <strong>Public</strong> consultation took place via a dedicated <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> web page, which was advertised through<br />

newspaper advertisements, Facebook, Twitter, Green Leaflet, targeted emails to stakeholders and<br />

internally through CEO Spotlight. Additional coverage was received through Southbank Local News and<br />

Residents 3000 website.<br />

6. In total 10 submissions were received from seven organisations and three individuals. The majority<br />

supported the strategy and the general vision. One submission was particularly opposed to the strategy.<br />

Attachment 2 details the submissions and how they were considered for incorporation in the final PLS.<br />

7. The changes resulting from the community consultation were consistent with the direction <strong>of</strong> the draft<br />

strategy, but provided additional details and resulted in an improved final draft.<br />

8. The primary objective <strong>of</strong> the PLS is to improve the quality, consistency and efficiency <strong>of</strong> night lighting in<br />

streets and public places so that places that are attractive by day will remain safe, comfortable and<br />

engaging after dark, energy will be used responsibly and nuisances associated with public lighting will be<br />

minimised.<br />

9. The estimated costs <strong>of</strong> fully implementing the PLS are $20.3 million over five years in excess <strong>of</strong> current<br />

budget allocations with annual operational savings <strong>of</strong> $1.8 million through energy efficiency. The costs are<br />

outlined in an action plan at chapter nine <strong>of</strong> the PLS and will be subject to future Council budget approval.<br />

Recommendation from management<br />

10. That the Future <strong>Melbourne</strong> Committee approves the <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> as attached to this<br />

report.<br />

Attachments:<br />

1. Supporting Attachment<br />

2. Details and results <strong>of</strong> the public consultation<br />

3. <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> (Final version)

SUPPORTING ATTACHMENT<br />

Page 2 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Attachment 1<br />

Agenda Item 6.4<br />

Future <strong>Melbourne</strong> Committee<br />

6 August <strong>2013</strong><br />

Legal<br />

1. No direct legal issues arise from the recommendation from management.<br />

Finance<br />

2. The strategy identifies the cost <strong>of</strong> implementation. This cost will be subject to future annual budget<br />

approval processes.<br />

Conflict <strong>of</strong> interest<br />

3. No member <strong>of</strong> Council staff, or other person engaged under a contract, involved in advising on or<br />

preparing this report has declared a direct or indirect interest in relation to the matter <strong>of</strong> the report.<br />

Stakeholder consultation<br />

4. For details <strong>of</strong> the external stakeholder consultation refer Attachment 2.<br />

Relation to Council policy<br />

5. The Draft PLS supports the Council’s broader strategic objectives and responds to many <strong>of</strong> the issues<br />

and aims identified in the following documents:<br />

5.1. <strong>Strategy</strong> for a Safer <strong>City</strong> 2011-<strong>2013</strong>.<br />

5.2. Docklands <strong>Public</strong> Realm Plan 2012.<br />

5.3. Greenhouse Action Plan 2006-2010 (Council Operations).<br />

5.4. Carlton Gardens Master Plan (2005).<br />

5.5. Open Space <strong>Strategy</strong> (2012).<br />

5.6. Southbank Structure Plan 2010.<br />

5.7. Urban Forest <strong>Strategy</strong> 2012-2032.<br />

5.8. Zero Net Emissions by 2020.<br />

5.9. Zero Net Emissions by 2020 (2008 update).<br />

5.10. Park Master plans (various).<br />

Environmental sustainability<br />

6. <strong>Public</strong> lights account for more than half <strong>of</strong> the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s electricity use. Furthermore, the public<br />

lighting system is a particularly conspicuous form <strong>of</strong> energy consumption that can send positive or<br />

negative messages about Council’s commitment to environmental sustainability. The Draft PLS reflects<br />

this commitment by addressing the following aims and objectives:<br />

6.1. Encourage the use <strong>of</strong> natural light for lighting in daylight hours.<br />

6.2. Promote and apply energy conservation practices.<br />

6.3. Reduce the amount <strong>of</strong> power consumed by public lighting.<br />

6.4. Consider and reduce impacts on biodiversity from the use <strong>of</strong> artificial lighting.<br />

6.5. Evaluate all new public lighting projects in terms <strong>of</strong> environmental sustainability criteria.<br />

6.6. Introduce a waste management plan for <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s public lighting system.<br />

6.7. Remove old assets when new ones are installed.<br />

1

Page 3 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Attachment 2<br />

Agenda Item 6.4<br />

Future <strong>Melbourne</strong> Committee<br />

6 August <strong>2013</strong><br />

PUBLIC LIGHTING STRATEGY <strong>2013</strong><br />

REPORT ON COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND<br />

SUBMISSIONS<br />

Page 1

Page 4 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Contents<br />

Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3<br />

Engagement approach ............................................................................................... 3<br />

Media coverage ........................................................................................................... 3<br />

Links published by other organisations ................................................................... 4<br />

Submission analysis .................................................................................................. 4<br />

Processing submissions ....................................................................................................... 4<br />

Key comments ........................................................................................................................ 5<br />

Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 5<br />

Submissions – Summary <strong>of</strong> responses .................................................................... 6<br />

Page 2

Page 5 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Introduction<br />

The aims <strong>of</strong> the community engagement process were to:<br />

1. Engage staff from relevant areas <strong>of</strong> Council to contribute expertise and assist with planning and<br />

implementation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong>.<br />

2. Provide the community and stakeholders with accessible information about public lighting<br />

infrastructure, and receive their feedback on the <strong>Strategy</strong>.<br />

3. Capture the expertise and ideas <strong>of</strong> the community and organisations affected by public lighting in the<br />

<strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>.<br />

4. Capture the expertise and ideas <strong>of</strong> other <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> residents and visitors about public<br />

lighting.<br />

Engagement approach<br />

5. The engagement approach focussed on broadly communicating with the public and enabling quick<br />

and accessible ways to provide targeted feedback on the draft <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong>.<br />

6. Communication channels used were:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> web page dedicated to the Draft <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong>. The page received<br />

425 page views (with 352 <strong>of</strong> those being unique) during the consultation period 9 April – 8 May<br />

<strong>2013</strong>).<br />

Newspaper advertisements<br />

Facebook and Twitter<br />

Green Leaflet (May <strong>2013</strong> edition)<br />

Targeted emails to stakeholders (government organisations, business and resident groups, etc)<br />

CEO Spotlight.<br />

Media coverage<br />

The draft <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> gained the following coverage:<br />

7. The community consultation period for the strategy was advertised in the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s<br />

corporate ad (which appeared in the <strong>Melbourne</strong> Times Weekly, <strong>City</strong> Weekly and Stonnington Leader<br />

w/c 22 April), and individual ads in the <strong>Melbourne</strong> Leader (29 April) and <strong>Melbourne</strong> Times Weekly (1<br />

May).<br />

8. Facebook and Twitter feeds were circulated through corporate and Eco city social media.<br />

9. Southbank Local News ran the story online on 16 April and again in issue 18 on 23 April.<br />

Page 3

Page 6 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Links published by other organisations<br />

10. Information on the proposal and consultation process was published on the websites <strong>of</strong> other<br />

organisations with links to the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> website. Organisations publishing links included:<br />

Residents 3000 included information on how to submit feedback on their website<br />

http://residents3000.net.au/<strong>2013</strong>/04/21/have-your-say-com-draft-public-lighting-strategy/.<br />

Submission analysis<br />

In total 10 submissions were received. The majority supported the strategy and the general vision to make<br />

the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> a public lighting city. One submission was particularly opposed to the strategy.<br />

Submissions were received from seven organisations listed below and three individuals.<br />

Yarra River Business Association<br />

Metropolitan Fire Brigade<br />

Streetworx<br />

Residents 3000<br />

Highlux<br />

Citelum<br />

Department <strong>of</strong> Planning and Community Development (DPCD)<br />

Processing submissions<br />

Further analysis <strong>of</strong> submissions determined what changes need to be made to the draft plan. Summarised<br />

comments were classified as consistent, support, include, no change and out <strong>of</strong> scope (to be referred to<br />

another party).<br />

Page 4

Page 7 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Key comments<br />

Maintenance<br />

Several submissions commented on importance <strong>of</strong> better surveillance and maintenance <strong>of</strong> public lighting.<br />

Special events<br />

Several submissions expressed support for using lighting to improve amenity <strong>of</strong> the city, specifically events,<br />

such as the Christmas light show and White Night.<br />

Light pollution and glare<br />

Some <strong>of</strong> the comments called for reduction in glare, especially from advertising signs. One <strong>of</strong> the<br />

submissions called for a significant reduction in all lighting.<br />

Support<br />

A significant number <strong>of</strong> submissions support the strategy.<br />

Conclusion<br />

The community engagement process and communications to promote community feedback to the <strong>Public</strong><br />

<strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> was planned in conjunction with the Corporate Affairs and Strategic Marketing<br />

branch.<br />

An internal reference group has assisted with developing the content <strong>of</strong> the strategy.<br />

The call for submissions to the Draft <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> was promoted widely and input was<br />

received from a diverse number <strong>of</strong> individuals and organisations.<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> the submissions received were supportive <strong>of</strong> the draft strategy. The changes resulting from the<br />

community consultation were consistent with the direction <strong>of</strong> the draft strategy, but provided additional<br />

details.<br />

The final draft has been improved with the significant input <strong>of</strong> key stakeholders and individuals.<br />

Page 5

Page 8 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

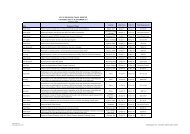

Submissions – Summary <strong>of</strong> responses<br />

Consistent<br />

Comments which are consistent with or support details <strong>of</strong> the draft strategy.<br />

Support<br />

Comments which expressed submitters’ support for the strategy.<br />

Include<br />

Comments which are relevant to the strategy and are included in the final draft.<br />

No change<br />

Comments that after consideration are inconsistent with <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> policy or key directions <strong>of</strong> the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s strategies or this strategy. Comments are not<br />

reflected in the final plan.<br />

Outside scope<br />

These comments do not relate to policies or issues that are within the direct control <strong>of</strong> the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> and will be referred to the appropriate organisation.<br />

The submissions are listed in the order in which they were received. Full copies <strong>of</strong> submissions are available on request by emailing ESG EMAIL<br />

Page 6

No.<br />

Name or<br />

Organisation<br />

Page 9 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Comment précis Chapter Action Response<br />

1 Con Angelatos Ongoing maintenance <strong>of</strong> existing lights is poor. Keeping the<br />

Lights<br />

Shinning<br />

2 Yarra River<br />

Business<br />

Association<br />

3 Metropolitan<br />

Fire Brigade<br />

Consistent/Outside<br />

scope<br />

The comment has been<br />

addressed in the maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

metered lighting, however,<br />

majority <strong>of</strong> public lighting is owned<br />

by Citipower. The comment has<br />

been passed on to Citipower.<br />

Support <strong>of</strong> the strategy. All Support No response necessary<br />

Overhead lighting should not impede overhead access for aerial trucks<br />

in case <strong>of</strong> a fire in a multi story building<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong>, Safety<br />

and<br />

Amenity<br />

Include<br />

Comment addressed and inserted<br />

into section 5.1.1.<br />

4 Streetworx Provides information on a Streetworx product, Enviro T5. N/A Outside scope Submission provides technical<br />

information on a product and has<br />

been forwarded to Design branch.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Definition <strong>of</strong> Precinct Character: this is important to give decoration and<br />

character to a precinct. E.g. Chinatown, Lygon Street, Arts Precinct.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Include<br />

Reference to CoM website<br />

describing precincts has been<br />

included.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Some <strong>of</strong> Hosier Lane residents would like to see an expansion <strong>of</strong><br />

dedicated street art lighting boxes as in the “<strong>City</strong> Lights” <strong>of</strong> Hosier Lane.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Outside scope<br />

Comment passed onto Design.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Interfacing with other portfolios: <strong>Lighting</strong> could also be interfaced with<br />

the Urban Forest <strong>Strategy</strong> and its vision for the CBD.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Consistent<br />

<strong>Lighting</strong> and tree management are<br />

already covered.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Colour: Some current lighting is “overdone” in colour. Suggested that<br />

colour could be in tune with weather and that warmer tones could be<br />

used in Winter with a cooler emphasis in Summer<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Outside scope<br />

Comment passed onto Design.<br />

Page 7

No.<br />

Name or<br />

Organisation<br />

Page 10 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Comment précis Chapter Action Response<br />

5 Residents 3000 Bourke Street Mall is visually depressing at night. Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

5 Residents 3000 Consider sensor lighting. Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

Outside scope<br />

Outside scope<br />

Comment passed onto Design.<br />

Specific/technical comment,<br />

passed onto Design.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Construction sites can <strong>of</strong>ten be poorly lit and cast shadow on<br />

pavements. Sometimes work sites remove regular street lighting.<br />

Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

Include<br />

Comment incorporated into<br />

Chapter 5.1.1<br />

5 Residents 3000 Suggested revision <strong>of</strong> Laneway lighting. Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

Consistent<br />

Draft <strong>Strategy</strong> already covers this<br />

topic.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Advertising signs should not be a distraction to motorists and can in<br />

themselves be considered to be visual “pollution”.<br />

Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

Consistent<br />

Draft <strong>Strategy</strong> already covers this<br />

topic.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Comments about poor maintenance <strong>of</strong> street lighting. Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

5 Residents 3000 Entrances to the underground loop should be well lit Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

Consistent/Out <strong>of</strong><br />

scope<br />

Consistent<br />

Metered lighting maintenance is<br />

undergoing improvement and this<br />

has been reflected in the Draft<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong>. Unmetered/Citipower<br />

lighting is not covered and the<br />

comment has been passed onto<br />

Citipower.<br />

Draft <strong>Strategy</strong> already covers this<br />

topic.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Glare into apartments from street lighting, advertising signage or highrise<br />

ro<strong>of</strong>top infrastructure should not negatively affect residential<br />

amenity.<br />

Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

Consistent<br />

Draft <strong>Strategy</strong> already covers this<br />

topic.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Interfacing with the Planning portfolio where applicants can be advised<br />

accordingly would be helpful.<br />

Safety &<br />

Amenity<br />

Consistent<br />

Planning already takes lighting<br />

strategy into account.<br />

5 Residents 3000 Supported special events, such as Christmas light show and White<br />

Night<br />

Attracting<br />

the evening<br />

crowd<br />

Support<br />

No response necessary<br />

Page 8

No.<br />

Name or<br />

Organisation<br />

Page 11 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Comment précis Chapter Action Response<br />

5 Residents 3000 Residents have reported poor synchrony <strong>of</strong> street lighting with daylight<br />

saving times on Latrobe between Russell and Exhibition<br />

5 Residents 3000 Taking advantage <strong>of</strong> privately supplied lighting by shop fronts,<br />

restaurants, cafes, and entrances to high rise towers and hotels could<br />

complement what the <strong>City</strong> has in place.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Sustainable<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Sustainable<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

5 Residents 3000 Comment about incentives <strong>of</strong>fered by Citipower Keeping the<br />

Lights<br />

Shining<br />

6 Highlux Concerned about the use <strong>of</strong> Australian Standards for P&V category<br />

lighting (because standards specify measured rather than perceived<br />

lux). This may be a barrier to use <strong>of</strong> LED technology.<br />

7 Citelum Draft <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> does not discuss contestability<br />

policy written in 2004 by the Essential Services Commission.<br />

8 Barry Clark Comments on light pollution as causing harm to humans and animals in<br />

the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong><br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Sustainable<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Keeping the<br />

Lights<br />

Shining<br />

8 Barry Clark Challenges the view that more lighting results in less crime. Safety and<br />

Amenity<br />

8 Barry Clark Recommends not using blue or white light (on health grounds) Safety and<br />

Amenity<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

Offers support for the overall structure <strong>of</strong> the document, but suggests<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional editing.<br />

Consistent<br />

Outside scope<br />

Outside scope<br />

Outside scope<br />

Referred back to Engineering<br />

Services team for operational<br />

comment and feedback to<br />

Citipower<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> covers this topic<br />

Comment passed onto Citipower.<br />

Recommend Highlux contact the<br />

Australian Standards (AS/NZS<br />

1158) Committee<br />

No action on advice from MAV.<br />

All Consistent The <strong>Strategy</strong> addresses issues <strong>of</strong><br />

light pollution and glare, although<br />

not to the extent requested in<br />

feedback.<br />

N/A<br />

No change<br />

No change<br />

Support and<br />

Consistent<br />

Comment is inconsistent with <strong>City</strong><br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> key direction <strong>of</strong><br />

using appropriate lighting to<br />

improve safety. The <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

comments extensively on avoiding<br />

over-lighting and lighting only<br />

when required.<br />

Recommend contact the<br />

Australian Standards (AS/NZS<br />

1158) Committee<br />

Final draft <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Strategy</strong> was<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essionally edited.<br />

Page 9

No.<br />

Name or<br />

Organisation<br />

Page 12 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Comment précis Chapter Action Response<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

The document doesn’t include a specific statement <strong>of</strong> how essential<br />

aspects <strong>of</strong> lighting (safety) in the city are addressed.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Include<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> was updated with the<br />

comment<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

Section 4.2.4 suggests the reader reference ‘lighting schemes’ for the<br />

Shrine <strong>of</strong> Remembrance; et al, yet specific details to assist in locating<br />

these schemes is absent<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

No change<br />

Any reference to location (e.g. on<br />

web) likely to be out <strong>of</strong> date in 5-<br />

10 years.<br />

8 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

Section 4.5 does not reference the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s Open Space<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>of</strong> 2012, despite the inclusion <strong>of</strong> Map 3.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Include<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> was updated accordingly.<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

Sections 4.6.1 - 4.6.3, Pt 3 and 4.6.5 fail to recognise the recent and<br />

proposed urban redevelopment on and adjacent to the Yarra River,<br />

particularly on Northbank west <strong>of</strong> Spencer Street, which provides new<br />

pedestrian and cycling connections into Victoria Harbour and<br />

Docklands. Whilst much <strong>of</strong> this area is within private ownership, a<br />

coordinated lighting strategy needs to be formulated for this important<br />

civic network<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

No change<br />

Comment in line with general<br />

thrust <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Strategy</strong>. This would<br />

be covered in precinct plans for<br />

the area.<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

Section 4.6.5 E-Gate hasn’t been developed yet, therefore not past<br />

tense reference.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

No change<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> will last 5-10 years and<br />

reads appropriately at the<br />

moment.<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

Section 4.7.1 whilst the notion <strong>of</strong> limiting sports event lighting ‘only<br />

when required’ is supported, this section appears to lack the more<br />

descriptive analysis <strong>of</strong> the role and performance that these lighting<br />

typologies can play within an urban context. Inclusion <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong><br />

context would be useful. In addition, this section fails to include<br />

reference to the nationally significant sports venues. Apart from the fact<br />

that some <strong>of</strong> these venues function beyond 10.00PM, they play a<br />

significant role as threshold statements into/out <strong>of</strong> the Hoddle grid. The<br />

lighting <strong>of</strong> AAMI stadium with low intensity LEDs is an excellent<br />

example <strong>of</strong> how to signify a precinct to connote different functions,<br />

either within the immediate precinct or as part <strong>of</strong> a broader city based<br />

function.<br />

Designing<br />

the<br />

Luminous<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Include<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> updated accordingly<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Section 5.1.1 is too specific and technical within the context <strong>of</strong> the<br />

objectives <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Strategy</strong>.<br />

Safety and<br />

Amenity<br />

No change<br />

Retain as this is critical for the<br />

overall direction <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

Page 10

No.<br />

Name or<br />

Organisation<br />

Development<br />

Page 13 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Comment précis Chapter Action Response<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

9 Department <strong>of</strong><br />

Planning and<br />

Community<br />

Development<br />

10 Natalie<br />

O’Connell<br />

Inclusion <strong>of</strong> Section 5.2.1 - 5.2.5 appears less strategic as opposed to<br />

implementation guidelines. The application <strong>of</strong> different colour <strong>of</strong> lights<br />

as a ‘quiet coding mechanism’ should be reduced to a single, concise<br />

paragraph under 5.2.<br />

Section 5.4.5 discuses content which seems to be partially discussed<br />

under Section 4.5 – Parks and Dark; particularly in reference to the<br />

issues <strong>of</strong> the ordering and spatial definition achieved through artificial<br />

illumination. Review for potential redundancy and inconsistency with<br />

content listed under section 4.5.<br />

Consideration should be given to how major cultural precincts perform<br />

during internationally significant events.<br />

The document does not include either responsive to, or support for new<br />

urban events which focus specifically on the illuminated form <strong>of</strong> the city,<br />

such as ‘White night’.<br />

Section 7.2.8, Consideration should be given to applying the principles<br />

<strong>of</strong> reducing, re-using and re-cycling for existing light assets. This may<br />

include a programme <strong>of</strong> either selling existing lighting assets identified<br />

for replacement or re-using in some format.<br />

Under ‘Designing the Luminous <strong>City</strong>’, consideration should be given to<br />

including the above noted strategies, particularly through an audit <strong>of</strong><br />

existing assets and the capacity for re-use or adaptation.<br />

<strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>of</strong> shared paths<br />

Using glowing plants instead <strong>of</strong> electrical street lighting<br />

Safety and<br />

Amenity<br />

Safety and<br />

Amenity<br />

Attracting<br />

the Evening<br />

Crowd<br />

Attracting<br />

the Evening<br />

Crowd<br />

Designing a<br />

Sustainable<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

No change<br />

No change<br />

Include<br />

No change<br />

Essentially the promotion <strong>of</strong> white<br />

light.<br />

Don’t agree. 4.5 is parks, 5.4.5 is<br />

more broadly plazas, forecourts<br />

and open space.<br />

The <strong>Strategy</strong> updated accordingly<br />

Not required. <strong>Strategy</strong> allows for<br />

other events to be targeted.<br />

Some other events were updated<br />

as per previous point.<br />

Include Updated in Section 7.2.7<br />

Action Plan Consistent Covered under “Keeping the lights<br />

Shining” and “Designing a<br />

Sustainable <strong>City</strong>” sections <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Action Plan.<br />

Safety and<br />

Amenity<br />

Designing a<br />

Sustainable<br />

<strong>City</strong><br />

Include Updated in section 5.0<br />

Outside scope<br />

No change, respondent advised<br />

accordingly.<br />

Page 11

Page 14 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Attachment 3<br />

Agenda Item 6.4<br />

Future <strong>Melbourne</strong> Committee<br />

6 August <strong>2013</strong><br />

<strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong><br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong><br />

1

Page 15 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> contents<br />

Executive summary ......................................................................................................... 4<br />

1.1 Origin and justification ....................................................................................... 4<br />

1.2 Scope and purpose ........................................................................................... 4<br />

1.3 Audience ........................................................................................................... 4<br />

1.4 Major themes .................................................................................................... 4<br />

1.5 Financial implications ........................................................................................ 5<br />

2 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 6<br />

2.1 Main objectives ................................................................................................. 6<br />

2.2 Scope ................................................................................................................ 6<br />

2.3 Format .............................................................................................................. 6<br />

3 Background to the strategy ...................................................................................... 8<br />

3.1 Changes to the 2002 strategy ........................................................................... 8<br />

3.2 Other Council strategies .................................................................................... 8<br />

3.3 Codes <strong>of</strong> practice .............................................................................................. 9<br />

3.4 Outdoor lighting ................................................................................................. 9<br />

3.5 Recent projects ................................................................................................. 9<br />

3.6 Stakeholders and communication ................................................................... 10<br />

3.7 Further work .................................................................................................... 10<br />

4 Designing the luminous city .................................................................................... 12<br />

4.1 Night and day .................................................................................................. 12<br />

4.2 Navigation lights .............................................................................................. 13<br />

4.3 Grids and lux ................................................................................................... 15<br />

4.4 Local colours ................................................................................................... 17<br />

4.5 Parks after dark ............................................................................................... 18<br />

4.6 The big splash ................................................................................................. 22<br />

4.7 The active community ..................................................................................... 24<br />

5 Safety and amenity ................................................................................................ 26<br />

5.1 Good measures .............................................................................................. 26<br />

5.2 White nights .................................................................................................... 28<br />

5.3 Form and light ................................................................................................. 30<br />

5.4 Peripheral vision ............................................................................................. 31<br />

6 Attracting the evening crowd .................................................................................. 34<br />

6.1 Making a spectacle ......................................................................................... 34<br />

6.2 Window dressing ............................................................................................. 35<br />

6.3 High lights ....................................................................................................... 36<br />

7 Designing a sustainable city ................................................................................... 37<br />

7.1 Thrills and spills .............................................................................................. 38<br />

7.2 Glowing greener .............................................................................................. 39<br />

8 Keeping the lights shining ...................................................................................... 42<br />

8.1 Maintain the light ............................................................................................. 42<br />

8.2 Learn and improve from practice ..................................................................... 43<br />

9 Action plan ............................................................................................................. 45<br />

9.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................... 45<br />

9.2 Summary <strong>of</strong> actions ........................................................................................ 45<br />

9.3 Cost implications <strong>of</strong> Designing a sustainable city ............................................ 50<br />

9.4 Cost implications <strong>of</strong> Safety and amenity .......................................................... 51<br />

9.5 Cost implications <strong>of</strong> Attracting the evening crowd............................................ 52<br />

9.6 Upgrading the public lighting system ............................................................... 52<br />

2

Page 16 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

9.7 Setting priorities .............................................................................................. 53<br />

Appendix 1: Glossary .................................................................................................... 54<br />

Appendix 2: Maps ......................................................................................................... 57<br />

3

Page 17 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Executive summary<br />

1.1 Origin and justification<br />

The <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> <strong>Public</strong> <strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> <strong>2013</strong> (the strategy) is an outcome <strong>of</strong> <strong>City</strong> Plan<br />

1999, which called for a comprehensive and integrated urban lighting strategy for all streets. The<br />

original strategy was adopted in 2002. However, the strategy is also part <strong>of</strong> a broader<br />

commitment to make <strong>Melbourne</strong> an even more liveable and attractive city. This revision was<br />

completed in <strong>2013</strong>.<br />

1.2 Scope and purpose<br />

The strategy aims to enhance people’s experience <strong>of</strong> the city after dark, while ensuring<br />

responsible energy use. It promotes improvements to safety and amenity, especially for<br />

pedestrians. In doing so, it also recognises that people’s sense <strong>of</strong> wellbeing results from a<br />

complex mix <strong>of</strong> factors. At night, these include way-finding and visual comfort, as well as road<br />

safety and personal security.<br />

The strategy recognises that brighter is not always better as far as outdoor lighting is concerned.<br />

Over-lighting <strong>of</strong> buildings or spaces dilutes dramatic effects, contributes to ‘sky glow’ and can<br />

result in other negative outcomes. Many <strong>of</strong> the objectives in this strategy aim to limit the extent or<br />

intensity <strong>of</strong> external illumination.<br />

The strategy acknowledges <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s characteristic brand <strong>of</strong> urban design. This has produced<br />

a public realm that is simple and low-key, yet also elegant and clearly structured. The strategy<br />

emphasises good, functional lighting rather than elaborate, decorative installations or ostentatious<br />

special effects. This approach is consistent with the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s commitment to<br />

environmental sustainability.<br />

This strategy draws on the experience gained from two decades <strong>of</strong> successful public lighting<br />

projects in the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>. It provides direction for public and private external lighting<br />

throughout the municipality. It covers the full range <strong>of</strong> outdoor illumination, from streetlights to<br />

lighting on individual sites and buildings. However, the strategy’s primary focus is on areas<br />

intended for public use and access.<br />

The strategy outlines issues and objectives, and sets priorities for lighting initiatives to 2023. In<br />

addition, the action plan sets out a range <strong>of</strong> specific initiatives to 2018.<br />

1.3 Audience<br />

The strategy is written for a broad audience. It is intended to be used by designers, developers,<br />

building owners and their agents (such as architects and lighting designers). In addition, the<br />

strategy will be used by planners and other staff within the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> to assess proposed<br />

lighting initiatives.<br />

1.4 Major themes<br />

The strategy is divided into five key themes:<br />

Designing the luminous city reinforces perceptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s physical form. The aim<br />

is to ensure a consistent, attractive and balanced approach to the design <strong>of</strong> lighting<br />

throughout the municipality.<br />

Safety and amenity aims to ensure that public lighting provides the required levels <strong>of</strong><br />

illumination so that the public realm is appropriate and safe.<br />

Attracting the evening crowd aims to promote and support <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s growing<br />

reputation as a 24-hour city. A vibrant and event-filled city is enhanced by innovative,<br />

well-considered lighting.<br />

4

Page 18 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

<br />

<br />

Designing the sustainable city promotes efficient technology, responsible management<br />

practices and other forms <strong>of</strong> energy conservation. This theme calls for large-scale<br />

replacement <strong>of</strong> inefficient mercury vapour lighting with more efficient and longer-lasting<br />

technologies.<br />

Keeping the lights shining calls for a proactive maintenance program for all lighting<br />

assets. This theme aims to deliver quality lighting and safety outcomes while managing<br />

operating costs and energy use.<br />

Although each <strong>of</strong> these themes outlines individual objectives, priorities and design preferences,<br />

the strategy should be read and applied as a whole.<br />

Recommended outcomes include better illumination along waterways, within parks and<br />

throughout neighbourhood shopping precincts. Special emphasis is given to upgrading lighting at<br />

the edges <strong>of</strong> streets, where most people walk. In addition, the strategy advocates better visibility<br />

within ancillary spaces along major streets. These tributary spaces include laneways, car parks,<br />

forecourts and recessed building entrances.<br />

1.5 Financial implications<br />

The strategy outlines a wide range <strong>of</strong> high level objectives and performance criteria to improve<br />

public lighting throughout the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>. However, the costs and benefits <strong>of</strong> these<br />

improvements cannot be fully quantified until individual projects are known.<br />

Some improvements will be managed within existing resources while a number <strong>of</strong> new activities<br />

are planned to improve public lighting and reduce energy consumption. The estimated costs <strong>of</strong><br />

implementing the strategy are $20.3 million over a five-year action plan. However, the strategy<br />

will also save the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> around $1.8 million per year and reduce annual greenhouse<br />

gas emissions by 8,000 tonnes.<br />

Most costs relate to two specific initiatives within the Designing a sustainable city theme: the<br />

replacement <strong>of</strong> mercury vapour lights ($3.6 million cost and $400,000 annual savings); and the<br />

replacement <strong>of</strong> high pressure sodium and metal halide lights ($13 million cost and $1.5 million<br />

annual savings).<br />

5

Page 19 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

2 Introduction<br />

2.1 Main objectives<br />

The primary objective <strong>of</strong> the strategy is to improve the quality, consistency and efficiency <strong>of</strong> night<br />

lighting in streets and other public spaces. If the strategy is successful, places that are attractive<br />

by day will remain safe, comfortable and engaging after dark. Energy will be used responsibly<br />

and sky glow, glare and other nuisances associated with outdoor lighting will be minimised.<br />

The strategy adds to existing codes <strong>of</strong> practice for outdoor illumination, including all relevant<br />

Australian standards.<br />

Appropriate, high quality lighting is important for all public places, although there is a natural<br />

tension between achieving this outcome and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The strategy<br />

seeks to balance these priorities by ensuring new lighting projects are considered on a case-bycase<br />

basis during the design and development phase.<br />

The strategy will help reconcile any competing aims by applying <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s characteristic brand<br />

<strong>of</strong> urban design. This will result in a public realm that is simple and low-key, yet also elegant and<br />

clearly structured. However, event lighting and temporary illuminated displays are encouraged,<br />

especially when linked to <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s festivals and other events.<br />

Due to the number <strong>of</strong> public lighting assets in the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>, the standard streetlight has<br />

the biggest impact on the appearance, amenity and environmental sustainability <strong>of</strong> public spaces.<br />

As such, this element is discussed in the most detail.<br />

2.2 Scope<br />

The strategy provides direction for public and private external lighting throughout the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong>. The strategy defines issues, identifies objectives and helps set priorities for lighting<br />

projects. It is a helpful resource for designers that outlines general performance standards but<br />

does not prescribe specific projects, precise measurements or technical details. Instead, the<br />

strategy focuses on achieving consistency across <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s outdoor lighting infrastructure.<br />

Performance standards and detailed applications are addressed separately as part <strong>of</strong> design<br />

standards, implementation plans and specific project proposals.<br />

The supporting action plan (refer to Section 9) is a summary <strong>of</strong> activities in the strategy, including<br />

accompanying costs, responsibilities and priorities.<br />

The strategy has a 10-year lifespan with a five-year action plan. Even though <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s<br />

physical character changes slowly over time, people’s aspirations change more rapidly. For this<br />

reason, the action plan will be reviewed and updated for a further five years after the 2017–18<br />

financial year.<br />

2.3 Format<br />

The strategy is divided into five key sections:<br />

Section 4<br />

Section 5<br />

Section 6<br />

Designing the luminous city: reinforcing perceptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s physical<br />

form<br />

Safety and amenity: improving pedestrian safety and amenity<br />

Attracting the evening crowd: bringing more activity to <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s public<br />

places<br />

6

Page 20 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Section 7<br />

Section 8<br />

Designing the sustainable city: minimising the negative environmental impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> outdoor lighting<br />

Keeping the lights shining: Actively maintaining quality lighting assets<br />

These themes introduce 18 separate lighting issues. Each issue is addressed by a set <strong>of</strong> lighting<br />

strategies presented in a standard format.<br />

Firstly, a concise statement <strong>of</strong> the strategy is outlined, emphasised in bold type. This is followed<br />

by a paragraph <strong>of</strong> explanatory text that expands on the meaning <strong>of</strong> the strategy, contains more<br />

precise directions and suggests a means for implementation. Finally, a set <strong>of</strong> bullet points provide<br />

explanations and comments on each <strong>of</strong> the strategies.<br />

Each strategy also includes maps and diagrams, which are referred to within the text and are<br />

attached at the end <strong>of</strong> this document. Although each lighting issue can be read independently,<br />

strategies under different headings are <strong>of</strong>ten related. For this reason, the document should be<br />

applied and understood as a whole.<br />

Finally, putting the strategy into effect requires a detailed action plan (refer to Section 9). This is<br />

needed to translate the general objectives <strong>of</strong> the strategy into a set <strong>of</strong> realistic lighting projects<br />

that can be achieved in a given timeframe.<br />

7

Page 21 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

3 Background to the strategy<br />

3.1 Changes to the 2002 strategy<br />

Originally released in 2002, the strategy was used extensively by <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> staff,<br />

developers and other government organisations. The original strategy was strongly supported<br />

and this revision maintains its integrity while ensuring current priorities and themes are<br />

incorporated.<br />

The 2002 strategy has influenced every major precinct development and plan since it was written.<br />

It has been used in the design <strong>of</strong> developments at Federation Square, Docklands and the QV site<br />

as well as the conversion <strong>of</strong> the central city and St Kilda Road Boulevard to white light.<br />

Key changes have been made to the following areas:<br />

updating dates, strategies, costs and savings estimates<br />

new section titled Keeping the lights shining<br />

rewrite <strong>of</strong> the Designing the sustainable city section<br />

refocus and reprioritisation for the upcoming five-year period.<br />

3.2 Other Council strategies<br />

The strategy originally responded to an initiative in the Council’s Municipal Strategic Statement<br />

and <strong>City</strong> Plan <strong>of</strong> 1999, which identifies the need for a comprehensive and integrated urban<br />

lighting strategy for all streets (see clause 5.1.6). This objective is part <strong>of</strong> a broader commitment<br />

to make <strong>Melbourne</strong> an even more liveable and attractive city. The strategy supports Council’s<br />

broader strategic objectives and responds to many <strong>of</strong> the issues and aims identified in the<br />

following documents:<br />

Policy for the 24 Hour <strong>City</strong> (2009)<br />

<strong>Strategy</strong> for a Safer <strong>City</strong> 2011–<strong>2013</strong><br />

Bicycle Plan 2012–2016<br />

Tree Policy<br />

Parks Policy<br />

Active <strong>Melbourne</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong> Retail <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong> Hospitality <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong>’s Parks and Gardens strategy (1995)<br />

JJ Holland Park Concept Plan 2008<br />

Docklands <strong>Public</strong> Realm Plan 2012<br />

Fitzroy Garden Master Plan Review Discussion Paper April 2010<br />

Carbon Neutral <strong>Strategy</strong><br />

Princes Park Master Plan (2012)<br />

Carlton Gardens Master Plan (2005)<br />

Fawkner Park Master Plan (2006)<br />

Flagstaff Gardens Master Plan (2000)<br />

Princes Park Ten Year Plan (1998)<br />

Royal Park Master Plan (1998)<br />

Newmarket Reserve Master Plan (2010)<br />

Open Space <strong>Strategy</strong> (2012)<br />

Southbank Structure Plan 2010<br />

Urban Forest <strong>Strategy</strong> 2012–2032<br />

Zero Net Emissions by 2020<br />

Zero Net Emissions by 2020 (2008 update)<br />

8

Page 22 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

3.3 Codes <strong>of</strong> practice<br />

The strategy augments existing codes <strong>of</strong> practice for outdoor illumination. The following<br />

Australian standards set minimum requirements for lighting in streets and other public places. All<br />

exterior lighting in the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> should meet or exceed these standards:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

AS/NZS 1158 Set: 2010 <strong>Lighting</strong> for roads and public spaces<br />

AS 4282-1997: Control <strong>of</strong> obtrusive effects <strong>of</strong> outdoor lighting<br />

AS 2560.2.3-2007: Sports lighting - Specific applications - <strong>Lighting</strong> for football (all codes)<br />

AS 2560.2.4-1986: Guide to sports lighting - Specific recommendations - <strong>Lighting</strong> for outdoor<br />

netball and basketball<br />

Unmetered lighting is managed under the requirements <strong>of</strong> the relevant distribution network<br />

service provider (DNSPs), Citipower and Jemena. As well as those requirements set out by the<br />

DNSPs, the following Acts, regulations and codes need to be adhered to when maintenance <strong>of</strong><br />

lighting unmetered assets is undertaken:<br />

Electricity Safety (Network Assets) Regulations (Vic) 1999 (Version No 002 Amended as at 7<br />

December 2005)<br />

Electricity Safety (Network Assets) Code 1997<br />

Electricity Safety Act 1998 (Vic) (Amended as at 21 October 2010)<br />

Planning and Environment Act 1987 (Vic) (Amended as at 30 June 2011)<br />

Environmental Protection Act 1970 (Vic) (Amended as at 1 July 2011)<br />

Code <strong>of</strong> Practice <strong>of</strong> electrical safety for work on or near high voltage electrical apparatus (the<br />

blue book) Victoria 2005<br />

Electricity Distribution Code, January 2006, Essential Services Commission<br />

Road Management Act 2004 (Vic) (Amended as at June 2011)<br />

Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (Vic) (Including duty <strong>of</strong> employers to consult<br />

employees who are directly affected by proposed changes to the workplace that may affect<br />

their health or safety, 1 January 2006)<br />

Occupational Health & Safety (Plant) Regulations 1995 (Amended as at 15 June 2001)<br />

Road Safety Act 1986 (Vic)<br />

Australian Standard AS1742.3 – 2009, Traffic control for Works on Roads<br />

Road Management Act 2004 (Vic), Worksite Safety – Traffic management code <strong>of</strong> practice<br />

3.4 Outdoor lighting<br />

Users <strong>of</strong> the strategy should also refer to the Civil Aviation Authority’s Manual <strong>of</strong> Operational<br />

Standards. This document provides safety criteria for searchlights, lasers and other powerful light<br />

sources that might affect aircraft operation.<br />

3.5 Recent projects<br />

This updated version <strong>of</strong> the strategy consolidates the lessons learned from a decade <strong>of</strong><br />

successful public lighting projects. However, the range <strong>of</strong> issues covered in the strategy is<br />

broader than any single project. These issues include technical, environmental and urban design<br />

considerations that affect public and private lighting throughout the municipality.<br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong> already has many fine examples <strong>of</strong> outdoor lighting. The strategy identifies a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> innovative or exemplary projects. Recent examples include:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Swanston Walk: Installation <strong>of</strong> plasma lighting<br />

Upgrading <strong>of</strong> cultural precincts including Lygon Street, Lonsdale Street and Chinatown<br />

Energy efficient lighting installations in the following locations:<br />

o Southgate, Lygon Street and Carlton (LED)<br />

9

Page 23 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

o<br />

o<br />

o<br />

Southbank (induction)<br />

Collins Street (active reactor)<br />

Royal Park (solar-powered LED)<br />

3.6 Stakeholders and communication<br />

The <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s strategy was commissioned by the Engineering Services branch. It was<br />

produced with the support <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> Council stakeholders.<br />

The Engineering Services branch has primary responsibility for managing metered public lighting<br />

in streets and parks, although the Parks Services branch is a major stakeholder in lighting the<br />

municipality’s large public open spaces. In addition, the <strong>City</strong> Design branch implements street<br />

improvements, and initiates policies and designs for other public places.<br />

The night appearance <strong>of</strong> the city is the product <strong>of</strong> public and private lighting. The <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong> can influence private outdoor illumination through the development planning process.<br />

However, a wider range <strong>of</strong> communication and collaboration is necessary to achieve complete<br />

synergy between public and private initiatives. For this reason, the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> needs to<br />

consult with other public authorities and key private sector stakeholders. The following<br />

organisations should be included in this dialogue:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Residents and facility owners<br />

CitiPower<br />

Jemena<br />

Neighbouring municipalities<br />

Yarra Trams<br />

Victorian Taxi Directorate<br />

Metropolitan Fire Brigade<br />

Astronomical Society <strong>of</strong> Australia<br />

Victorian Government<br />

o Victoria Police<br />

o Department <strong>of</strong> Infrastructure<br />

o Department <strong>of</strong> Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure<br />

o Places Victoria<br />

o VicRoads<br />

o VicTrack<br />

<strong>Lighting</strong> contractors who provides services in<br />

o design<br />

o maintenance and services<br />

o product supply.<br />

The <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong> will work collaboratively with electricity distributors to develop and<br />

implement plans to replace inefficient, unmetered street lights with more efficient ones, while<br />

maintaining appropriate illumination levels.<br />

Promoting this strategy and its successes to designers, developers, other organisations and the<br />

wider community will be important to help achieve better lighting solutions. Support for the<br />

strategy will be sought from surrounding municipalities and the Victorian Government. Feedback<br />

will be obtained via social media and other web-based platforms.<br />

3.7 Further work<br />

This strategy is the main document outlining the public lighting approach for the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong>. It avoids technical information or detailed design, and is relevant to a wide range <strong>of</strong><br />

users and conditions. It is also easy-to-use and jargon-free.<br />

10

Page 24 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

Precise specifications are inappropriate for a long-term strategy <strong>of</strong> this type as lighting technology<br />

is evolving rapidly. Reference to specific dimensions, products and applications could soon be<br />

obsolete.<br />

As a result, the strategy is supported by specific technical information. The Engineering Services<br />

branch has prepared performance specifications for street lighting in the municipality. Together<br />

with the strategy, these design standards provide precise guidance for lighting in the public realm.<br />

Design standards have been produced for the following lighting topics:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

F310 Street lighting, Street set<br />

F340 Street lighting, Parkville set<br />

F350 Park lighting, Regular set<br />

F360 Street lighting, Swanston Street set.<br />

New design standards are needed to establish good lighting practice in other situations. Each<br />

design standard should address energy conservation and provide advice on how to prevent<br />

nuisance from intrusive or waste light. Priority topics include:<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Contemporary architecture<br />

Heritage architecture<br />

<strong>Public</strong> art<br />

Shop window displays<br />

Security lighting<br />

Landscape features and large sites<br />

Outdoor public events.<br />

Management <strong>of</strong> private lighting is critical to help achieve the objectives <strong>of</strong> the strategy. Further<br />

work is needed to ensure planning schemes cater for the requirements <strong>of</strong> the strategy. Key areas<br />

to consider are:<br />

<br />

<br />

Establish planning requirements for the use <strong>of</strong> lighting on awnings and verandas which<br />

exceed a certain width (e.g. greater than 3 m in places such as Elizabeth Street, between<br />

Flinders Street and Flinders Lane).<br />

Ensure planning schemes adequately manage the use <strong>of</strong> reflective glass to reduce glare<br />

to neighbouring properties.<br />

11

Page 25 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

4 Designing the luminous city<br />

Reinforcing how <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s physical form is seen<br />

Outdoor lighting should reinforce how <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s urban form is seen, and promote appreciation<br />

<strong>of</strong> individual works <strong>of</strong> architecture. To meet these objectives, lighting concepts should encompass<br />

the entire city, focus on each <strong>of</strong> its neighbourhoods and be fully integrated with the form and<br />

character <strong>of</strong> individual buildings or spaces. As such, lighting designers need to address a broad<br />

range <strong>of</strong> issues. Traditional concerns such as road safety and personal security remain<br />

fundamental and are addressed in detail in Section 5. However, emphasis should also be given to<br />

the expressive potential <strong>of</strong> light and the contribution it makes to <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s night image and<br />

identity.<br />

4.1 Night and day<br />

Familiarity and surprise after dark<br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong> is a different place after dark. Good lighting should enhance the transformation from<br />

day to night. In doing so, it should produce positive changes that enrich people’s experiences and<br />

enhance their understanding <strong>of</strong> the city. To achieve this, lighting should call attention to shifts in<br />

use and meaning that follow the end <strong>of</strong> the working day. After dark, the night image <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong><br />

should be cohesive and familiar. Important paths, nodes and markers should remain legible and<br />

recognisable to people.<br />

Outdoor illumination should also produce some surprises. <strong>Lighting</strong> can reveal elements and<br />

relationships that are less obvious during the day. It can alter the appearance <strong>of</strong> spaces or<br />

objects, either playfully or provocatively. However, the combined effect <strong>of</strong> these transformations<br />

must be engaging rather than alienating. For this to occur, changes should be set within the same<br />

basic framework <strong>of</strong> paths, precincts and landmarks that organise <strong>Melbourne</strong> during the day.<br />

4.1.1 Reinforce perceptions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s physical identity and characteristic urban<br />

structure.<br />

Ensure that defining elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s physical character are legible after dark.<br />

4.1.2 Balance opportunities to transform places with light against the need to present a<br />

coherent city image.<br />

Compare people’s daytime perception <strong>of</strong> the city with their experience after dark. Ensure the<br />

dominant impression is that <strong>of</strong> continuity between day and night. Against this familiar backdrop,<br />

use illumination to alter the appearance and importance <strong>of</strong> objects. Highlight buildings,<br />

infrastructure and other elements <strong>of</strong> urban fabric in areas <strong>of</strong> the city that lack distinctive daytime<br />

features. Apply these transformations selectively to delight and surprise viewers, and also to<br />

express changes in use and status from day to night.<br />

4.1.3 Call attention to the distinctive patterns <strong>of</strong> activity that animate the city at night.<br />

Use night lighting to orient people and help them find their way around the city. Ensure the city’s<br />

network <strong>of</strong> paths, nodes, edges and landmarks is clearly visible, especially in areas that attract<br />

large numbers <strong>of</strong> pedestrians after dark.<br />

4.1.4 Extend <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s distinctive brand <strong>of</strong> urban design to the city’s public lighting<br />

system.<br />

Adopt a simple, low-key approach to lighting in the public realm. Rely on functional lighting to<br />

express urban form and identity. Produce elegant designs <strong>of</strong> consistently high quality. Avoid<br />

12

Page 26 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

attracting undue attention to light fittings, either by day or by night. Ensure the collective result <strong>of</strong><br />

lighting installations is to enhance the structure <strong>of</strong> public space.<br />

4.2 Navigation lights<br />

<strong>Lighting</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s landmarks<br />

Not every building can be a landmark. Although skilful illumination can enhance the most banal<br />

object, having too many points <strong>of</strong> emphasis dilutes its impact. This approach can also be a<br />

nuisance and sets a poor example for responsible energy use. For these reasons, most <strong>of</strong> the<br />

city’s fabric should appear as a backdrop to a few special buildings and places. In most cases,<br />

the features that stand out should match key reference points in people’s understanding <strong>of</strong> the<br />

city. To achieve this, landmarks do not have to be large, conspicuous or concentrated in<br />

<strong>Melbourne</strong>’s busiest locations.<br />

Every part <strong>of</strong> the city should have its own markers. These should be chosen in relation to local<br />

patterns <strong>of</strong> form and use that may not extend further than a few blocks. In the same way,<br />

landmarks do not have to be ‘public’ in the full sense <strong>of</strong> this word. Many privately-owned buildings<br />

help to articulate the city’s form and functions. Nevertheless, when sites for feature lighting are<br />

assessed, it is important to distinguish between displays that promote private interests and those<br />

that make a genuine contribution to the city’s legibility.<br />

4.2.1 Restrict permanent feature lighting to buildings, landscapes and other artefacts<br />

that have special public significance.<br />

To receive landmark status, elements should have one or more <strong>of</strong> the following attributes<br />

or functions:<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

(d)<br />

(e)<br />

express important historic associations or symbolic values<br />

accommodate major public institutions or events<br />

attract large numbers <strong>of</strong> visitors<br />

occupy prominent locations, with obvious connections to other important elements <strong>of</strong><br />

urban structure<br />

display exceptional size, unique shape, or materials and details <strong>of</strong> unusually high quality.<br />

A building’s importance is a function <strong>of</strong> its use, appearance and location. Highlighting too many<br />

buildings undermines the status <strong>of</strong> genuine landmarks. Unrestricted floodlighting <strong>of</strong> buildings<br />

wastes energy and can create nuisance.<br />

4.2.2 Illuminate significant buildings and other landmarks on the edge <strong>of</strong> the Central<br />

Business District (CBD) and around the central city<br />

Today the central city encompasses the CBD, Southbank and Docklands. Examples <strong>of</strong> this type<br />

<strong>of</strong> landmark include the following structures and spaces:<br />

- bridges across the Yarra River<br />

- Federation Square<br />

- Flinders Street Station<br />

- Forum Theatre<br />

- Grand Hotel<br />

- Queen Victoria Market<br />

- Spencer Street power station<br />

- St Patrick’s Cathedral.<br />

A good example <strong>of</strong> this work is the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s lighting scheme for Parliament House,<br />

Spencer Street Station and the Treasury Building.<br />

13

Page 27 <strong>of</strong> 72<br />

A number <strong>of</strong> open spaces occur around the perimeter <strong>of</strong> the central city. These include<br />

waterways, parkland, rail yards and left over spaces that form when different street patterns meet.<br />

Such places provide unrestricted views <strong>of</strong> adjacent city buildings.<br />

4.2.3 Within the central city, illuminate significant buildings in settings that allow good<br />

visibility.<br />

Consider the following situations:<br />

(a) buildings set back from the street edge<br />

(b) buildings that sit within their own grounds<br />

(c) buildings that occupy major street corners or entire city blocks<br />

(d) buildings at the end <strong>of</strong> major street corridors<br />

(e) buildings that face parks, gardens and other public reserves.<br />

Examples <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> landmark include the following buildings:<br />

- Royal Mint<br />

- State Library<br />

- St Paul’s Cathedral<br />

- Supreme Court<br />

- Town Hall<br />

A good example <strong>of</strong> this approach is the <strong>City</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s recent lighting scheme for the Old<br />

General Post Office. The central city defines <strong>Melbourne</strong>’s cultural and commercial heart. As a<br />

result <strong>of</strong> its importance, this area should have more landmarks than other parts <strong>of</strong> the city.<br />

Central city sites are <strong>of</strong>ten hemmed in by neighbouring development. A foreground space gives<br />

prominence and allows large buildings to be viewed comfortably. High ambient light levels in city<br />