The Standard 22 June 2014

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

JUNE <strong>22</strong> TO 28, <strong>2014</strong><br />

THE STANDARD STYLE / ARTS / BOOKWORM 29<br />

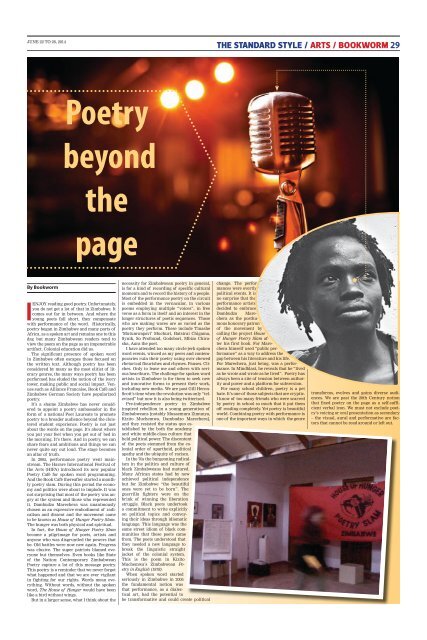

Poetry<br />

beyond<br />

the<br />

page<br />

By Bookworm<br />

I<br />

ENJOY reading good poetry. Unfortunately,<br />

you do not get a lot of that in Zimbabwe. It<br />

comes out far in between. And where the<br />

young poets fall short, they compensate<br />

with performance of the word. Historically,<br />

poetry began in Zimbabwe and many parts of<br />

Africa, as a spoken art and remains one to this<br />

day, but many Zimbabwean readers tend to<br />

view the poem on the page as an impenetrable<br />

artifact. Colonial education did us.<br />

<strong>The</strong> significant presence of spoken word<br />

in Zimbabwe often escapes those focused on<br />

the written text. Although poetry has been<br />

considered by many as the most elitist of literary<br />

genres, the many ways poetry has been<br />

performed has eluded the notion of the ivory<br />

tower, making public and social impact. Venues<br />

such as Alliance Francaise, Book Café and<br />

Zimbabwe German Society have popularized<br />

poetry.<br />

It’s a shame Zimbabwe has never considered<br />

to appoint a poetry ambassador in the<br />

form of a national Poet Laureate to promote<br />

poetry to a broader audience beyond the cloistered<br />

student experience. Poetry is not just<br />

about the words on the page. It's about where<br />

you put your feet when you get out of bed in<br />

the morning. It’s there. And in poetry, we can<br />

share fears and ambitions and things we can<br />

never quite say out loud. <strong>The</strong> stage becomes<br />

an altar of truth.<br />

In 2005, performance poetry went mainstream.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Harare International Festival of<br />

the Arts (HIFA) introduced its now popular<br />

Poetry Café for spoken word programming.<br />

And the Book Café thereafter started a monthly<br />

poetry slam. During this period the economy<br />

and politics were about to implode. It was<br />

not surprising that most of the poetry was angry<br />

at the system and those who represented<br />

it. Dambudzo Marechera was unanimously<br />

chosen as an expressive embodiment of radicalism<br />

and dissent and the movement came<br />

to be known as House of Hunger Poetry Slam.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hunger was both physical and spiritual.<br />

In fact, the House of Hunger Poetry Slam<br />

became a pilgrimage for poets, artists and<br />

anyone who was disgruntled the powers that<br />

be. Old battles were now new again. Progress<br />

was elusive. <strong>The</strong> super patriots blamed everyone<br />

but themselves. Even books like State<br />

of the Nation: Contemporary Zimbabwean<br />

Poetry capture a lot of this message poetry.<br />

This poetry is a reminder that we never forget<br />

what happened and that we are ever vigilant<br />

in fighting for our rights. Words mean everything.<br />

Without words, without the spoken<br />

word, <strong>The</strong> House of Hunger would have been<br />

like a bird without wings.<br />

But in a larger sense, what I think about the<br />

necessity for Zimbabwean poetry in general,<br />

is for a kind of recording of specific cultural<br />

moments and to record the history of a people.<br />

Most of the performance poetry on the circuit<br />

is embedded in the vernacular, in various<br />

poems employing multiple “voices”, in free<br />

verse as a form in itself and an interest in the<br />

longer structures of poetic sequences. Those<br />

who are making waves are as varied as the<br />

poetry they perform. <strong>The</strong>se include Tinashe<br />

‘Mutumwapavi’ Muchuri, Batsirai Chigama,<br />

Synik, So Profound, Godobori, Mbizo Chirasha,<br />

Aura the poet.<br />

I have attended too many circle-jerk spoken<br />

word events, winced as my peers and contemporaries<br />

ruin their poetry using over chewed<br />

rhetorical flourishes and rhymes. Pauses. Cliches.<br />

Only to leave me and others with serious<br />

heartburn. <strong>The</strong> challenge for spoken word<br />

artists in Zimbabwe is for them to seek new<br />

and innovative forms to present their work,<br />

including new media. We are past Gill Heron-<br />

Scott’s time when the revolution was only “televised”<br />

but now it is also being twitterised.<br />

Pre-independence poetry in Zimbabwe<br />

inspired rebellion in a young generation of<br />

Zimbabweans [notably Musaemura Zimunya,<br />

Kizito Muchemwa, Dambudzo Marechera],<br />

and they resisted the status quo established<br />

by the both the academy<br />

and white middle-class culture that<br />

held political power. <strong>The</strong> discontent<br />

of the poets stemmed from the colonial<br />

order of apartheid, political<br />

apathy and the ubiquity of racism.<br />

In the 70s the burgeoning radicalism<br />

in the politics and culture of<br />

black Zimbabweans had matured.<br />

Many African states had by now<br />

achieved political independence<br />

but for Zimbabwe “the beautiful<br />

ones were yet to be born”. <strong>The</strong><br />

guerrilla fighters were on the<br />

brink of winning the liberation<br />

struggle. Black poets undertook<br />

a commitment to write explicitly<br />

on political topics and conveying<br />

their ideas through idiomatic<br />

language. This language was the<br />

same street idiom of black communities<br />

that these poets came<br />

from. <strong>The</strong> poets understood that<br />

they needed a new language to<br />

break the linguistic straight<br />

jacket of the colonial system.<br />

This is the poem in Kizito<br />

Muchemwa’s Zimbabwean Poetry<br />

in English (1978).<br />

When spoken word started<br />

seriously in Zimbabwe in 2005<br />

the fundamental notion was<br />

that performance, as a dialectical<br />

art, had the potential to<br />

be transformative and could create political<br />

change. <strong>The</strong> performances<br />

were overtly<br />

political events. It is<br />

no surprise that the<br />

performance artists<br />

decided to embrace<br />

Dambudzo Marechera<br />

as the posthumous<br />

honorary patron<br />

of the movement by<br />

calling the project House<br />

of Hunger Poetry Slam after<br />

his first book. For Marechera<br />

himself used “public performance”<br />

as a way to address the<br />

gap between his literature and his life.<br />

For Marechera, just being, was a performance.<br />

In Mindblast, he reveals that he “lived<br />

as he wrote and wrote as he lived”. Poetry has<br />

always been a site of tension between authority<br />

and power and a platform for subversion.<br />

For many school children, poetry is a pet<br />

hate. It’s one of those subjects that are cryptic.<br />

I know of too many friends who were scarred<br />

by poetry in school so much that it put them<br />

off reading completely. Yet poetry is beautiful<br />

world. Combining poetry with performance is<br />

one of the important ways in which the genre<br />

transforms, evolves and gains diverse audiences.<br />

We are past the 20th Century notion<br />

that fixed poetry on the page as a self-sufficient<br />

verbal icon. We must not exclude poetry’s<br />

voicing or oral presentation as secondary<br />

– the visual, aural and performative are factors<br />

that cannot be read around or left out.