A Laboratory Ideas

A Laboratory Ideas

A Laboratory Ideas

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

... ,.. I<br />

__}

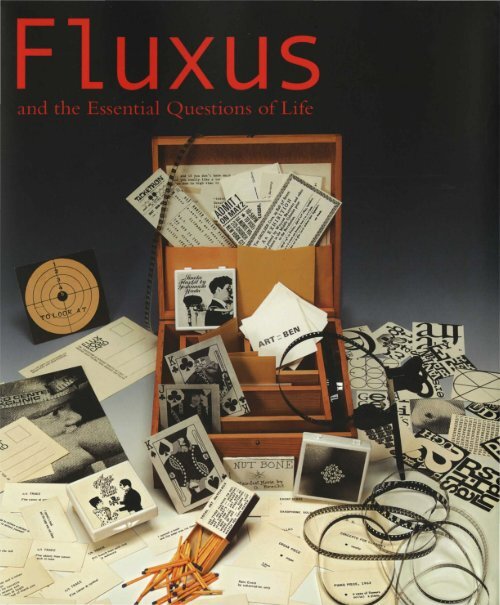

Fluxus and the Essential Questions ofLife

, ~ ~~~~c- ~- ~:#.. -- ~:::: ___- W 114 _ JOHNSON --cO' _ _ _- •<br />

.----

uxus<br />

and the Essential Questions of Life<br />

Edited by<br />

Jacquelynn Baas<br />

With Contributions by<br />

Jacquelynn Baas<br />

Ken Friedman<br />

Hannah Higgins<br />

Jacob Proctor<br />

Hood Museum of Art, D artmouth College • H anover, N ew Hampshire<br />

in Association with<br />

The University of Chicago Press • C hicago and London

J ~cq u e l y nn B~~ s is director emeritus of<br />

the Unive rsity ofC~ liforni~ Berkeley<br />

Art Museum ~nd P~cific Film Archive.<br />

Prev iously she se rve d ~ s director of th e<br />

Hood Museum of Art. She is the ~u th or,<br />

co~ uth or, or editor of m ~ny publi c~ tion s,<br />

in cl uding S111ile of th e Buddha : East em<br />

Philosophy aud Hlestem A rt.fimll J\1Io 11et<br />

to Today (C~ li forn i~ . 2005), Buddlw<br />

Mi11d iu Coute111pomry Art (C~ liforn i ~.<br />

2004), Leamiug i\1/iud: Expericuce iuto<br />

A rt (C~ liforni ~. 2010) , Meas ure o(Ti111e<br />

(C~ l ifo rni ~ . 2007), Darrell Waterstou:<br />

Rcprcscutiug the liwisible (C h ~rt~. 2007),<br />

~ nd T he ludcpeudcut C roup : Postll'ar Britaiu<br />

nud the Aesth etics of Pleuty (MIT, 1990).<br />

Published by<br />

Hood Museum of Art,<br />

D~rtmouth Coll ege<br />

1-l ~ n over, New 1-l ~ mp s hire 03755<br />

ww\v. hood n1u se u n1.da rtmou th .edu<br />

and<br />

The Unive rsit y ofC hi c~go Press,<br />

C hi c~go 60637<br />

The Unive rsity ofChi c~go Press, Ltd. ,<br />

London<br />

© 20.11 by T he Trustees of<br />

Dartmouth Coll ege<br />

All rights reserved. Published 2011.<br />

Every effort h ~s been m~d e to identify<br />

~ nd l oc~ t e th e ri ghtful copyri ght holder<br />

of a llm~t e ri ~ l not s p ec ifi c~ ll y<br />

commissio ned for use in this p ubli c~ ti o n<br />

and to secure pennission , w here<br />

applica ble, for rem e of ~ II such materi al:<br />

Any error, 01ni ss ion, or £1 ilure to obtain<br />

authori za tion with respect to 1nateri al<br />

copyrighted by other sources has been<br />

either un~void~bl e or unint e nti o n~l.<br />

The editors ~nd publishers welcome ~ n y<br />

info rm ~ tion th~t would ~ ll ow them to<br />

correct future reprints.<br />

The c~ t ~ l og u e ~ nd ex hibition titled Fluxus<br />

aud the Esseutinl Q uestious of Life were<br />

o r g ~nized by th e Hood Muse um of Art<br />

~ nd ge nerously supported by C onst~n ce<br />

~nd Wa lter Burke, C l~ ss of 1944, the<br />

R~ y Winfield Smith 19 18 Fund, ~nd the<br />

Marie-Louise and s~ mu e l R.. R.o se nrh ~ l<br />

Fund.<br />

Exhibition schedule<br />

Hood Muse um of Art,<br />

D~rtmouth College<br />

Apri l 16-August 7, 20 11<br />

Grey Art Ga llery,<br />

New York Universit y<br />

September 9-December 3, 2011<br />

University of Michiga n<br />

Museum of Art<br />

February 25-May 20, 2012<br />

Ed ited by Nils Nadeau<br />

Designed by Glenn Suokko<br />

Printed by Capit~ l O ffset Co mp~n y<br />

T he following images are photographed<br />

by Jeffrey Nintzel: cover, fro ntispiece,<br />

ca talogue numbers 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10,<br />

13, 15, 17, 22, 26, 30, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36,<br />

37, 42 , 46, 52, 55 , 56, 59, 63,64, 65 , 70,<br />

72, 73, 74, 78, 79, 80, 85, 90, 93, 96, 102,<br />

106, 107, 11 0, Ill , 11 2, 1"13, 116<br />

Cover and b~ c k cover: Flux Year Box 2,<br />

1966, fi ve-compartment wooden box<br />

containing work by various artists . Hood<br />

Museum of Art, Dartmouth Coll ege,<br />

George Maciun as Memori~ l Collection:<br />

Purchased through the Wi lliam S. Rubin<br />

Fund; GM.987.44.2 (ca t. 6)<br />

Frontispiece: George M~ c iuna s, Btuglnry<br />

Fluxkit, 1971 , seven-compartment<br />

pl ast ic box containing seven keys.<br />

Hood Muse um of Art, D~rt m ou th<br />

College, George Maciunas Memori al<br />

Coll ection: Gift of the Friedman Family;<br />

GM.986.80 .1 64 (c~t. 22) © Courtesy of<br />

Billie Maciun ~s<br />

Printed in the United S t ~ t es of America<br />

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5<br />

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-03359-4 (pa per)<br />

ISBN-10: 0-226-03359-7 (paper)<br />

Libr~ry of Congress Cataloging-in<br />

Publication Data<br />

Flu x us ~nd the esse nri ~ l questions of<br />

life I edited by J ~c qu e l y nn Baas; w ith<br />

contributions by Jacquelyn n Ba~ s .<br />

(et ~ I.] .<br />

p. Cnl.<br />

Includes bibliographica l references.<br />

Exhibition schedul e: Hood Museum of<br />

Art, Dartmouth College: April 16-August<br />

7, 201 1; Grey Art G~ ll e r y , New Yo rk<br />

University: September 9-December 3,<br />

20 1"1 ; Universit y ofM i c hi g~ n Museum of<br />

Art: Febru ary 25-May 20, 2012.<br />

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-03359-4 (pbk. : alk .<br />

paper)<br />

ISBN-10: 0-226-03359-7 (pbk. : alk.<br />

p~p e r ) l. Flu xus (Group of ~rtis t s)<br />

.Ex hibitions. 2. Art, Modern-20th<br />

century-Exhibitions. I. Baa s, Jacquelynn ,<br />

1948- II. Hood Muse um of Art.<br />

N6494. F55F57 2011<br />

709.04'60747423-dc22<br />

2010051 925<br />

This paper meets the requirements of<br />

ANSI/ NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of<br />

Paper).

Contents<br />

Lenders to the Exhibition<br />

Preface<br />

Juliette Bianco<br />

Acknowled gments<br />

Jacquelynn Baas<br />

I. Introduction<br />

Jacquelynn Baas<br />

2. Food: The R aw and the Fluxed<br />

H annah Higgins<br />

3. George M aciunas's Politics o f Aesthetics<br />

J acob Proctor<br />

4. Flu xus: A <strong>Laboratory</strong> of <strong>Ideas</strong><br />

Ken Friedman<br />

vii<br />

ix<br />

xiii<br />

1<br />

13<br />

23<br />

35<br />

CATALOGUE OF THE EXHIBITION 45<br />

5. Flux us and the Essential Questio ns of Life 4 7<br />

Jacquelynn Baas<br />

Art (What's It Good Fo r)? 47 C hange? 49<br />

D anger? 52 D eath ? 55 Freedom ? 56 God ? 59<br />

H appiness? 60 H ealth? 64 Love? 66<br />

N o thingness? 70 Sex? 71 Staying Alive? 74<br />

Time? 76 What A m I? 79<br />

Illustrated List of W orks 85<br />

Selected Bibliography 131

•<br />

• •<br />

•<br />

f<br />

• •<br />

•<br />

• •<br />

•<br />

f<br />

•<br />

f<br />

•

4<br />

Fluxus: A <strong>Laboratory</strong> of <strong>Ideas</strong><br />

Ken Friedman<br />

In 1979, H arry Rube labeled Fluxus " the most<br />

radical and experimental art movement of the<br />

sixties ." 1 In those days, few believed him. Three<br />

decades later, more people might feei this to be<br />

o, but few could say why. We might answer that<br />

question ftrst by noting that experimentati on is<br />

ultimately marked by qualities that emerge in a<br />

laboratory, scientific or otherw ise. In this essay I<br />

will exa mine Fluxus as an international laboratory<br />

of ideas- a meeting ground and workplace<br />

for artists, composers, designers, and architects, as<br />

wel l as economists, mathemati cians, ballet dancers,<br />

chefs, and even a wou ld-be theologian. W e<br />

ca me from three continents-Asia, Europe, and<br />

N orth America. At first, many critics and artists<br />

labeled us charl atans; the general public ignored<br />

us. Later they called us artists; ftn ally they saw us<br />

as pioneers of one kind or another. The conceptual<br />

challenge of this essay by a Flux us insider,<br />

then, lies in trying to identify just what kind of<br />

. .<br />

piOneers we were.-<br />

Emerging from a community that bega n in<br />

the 1950s, 3 Fluxus had gained its name and its<br />

identity by 1962. In different places on different<br />

continents, meetings, friendships, and relationships<br />

brought va rious constellations of people<br />

Opposite:<br />

Ken Friedman, A Fl11x Corsage, 1966-76, clea r plastic box wi th<br />

paper label on lid containing seeds. Hood Museum of Art, Danmouth<br />

College, George Ma ciunas Memori al Coll ection: Gift of<br />

the Friedman Fami ly; GM.986.80.40 9 (ca t. 17).<br />

into contac t w ith one another. The peripatetic<br />

George Maciunas managed to meet many of<br />

those w ho would cohere into Flu xus in the ea rly<br />

1960s. H e had been trying to create an avantga<br />

rde art gallery named AG that was already<br />

nearl y bankrupt on the day it opened. N ext,<br />

he wanted to publish a magazine-really an<br />

encyclopedia of sorts-documenting the most<br />

adva nced art, m usic, literature, film, and design<br />

work being done anywhere in the world. George<br />

had an ambitious plan for va rious interlocking<br />

editorial boards and publishing committees, but<br />

it never ca me to fruition. (H e was better at planning<br />

than he was at fundraising or leadership.)<br />

By 1962, George was in Germany, developing a<br />

series of festivals for the· public presentation of<br />

work that he planned to publish in the magazine<br />

he still had on the back burner. The magazine<br />

was to have been called Flux us, so the festiva l was<br />

ca lled Flux us.<br />

Nine artists and composers ca me together<br />

in Wiesbaden to perform: Dick Higgins, Alison<br />

Knowles, Addi K0pcke, George Maciunas,<br />

N am June Paik, Benj amin Patterson , Wolf<br />

Vostell , Karl Erik W elin, and Emmett Williams.<br />

The German press liked the name of the fe tival<br />

and bega n referring to the Wiesbaden nine<br />

as die Flux us leute-"the Flux us people"- and<br />

the name stuck. 4 Other artists became associated<br />

with Flux us through contac t w ith members of

this burgeoning international ava nt-garde community,<br />

including such varied prac titioners as<br />

Joseph Beuys, H enning Christiansen, Robert<br />

Filliou, Bengt af Klintberg, Willem de Ridder,<br />

and Ben Vautier. Others joined later, including<br />

Jeff Berner, Geoffrey H endricks, Milan Kniza k,<br />

and me. 5<br />

It is important to note that Flux us was a<br />

community rather than a collective with a common<br />

artistic and political program. 6 (None of<br />

the artists signed the suppo ed Flux us manifestoes<br />

that George M aciunas created- not even<br />

George himsel f. ) Several streams of thought meet<br />

in th e work and prac tices of the Fluxus community.<br />

One stream is the well-known Fluxus<br />

relationship to the teaching of John Cage, and<br />

to related lines of practice reaching back to Z en<br />

Buddhism. 7 Another stream is the more oblique<br />

but still strong relationship to ea rlier- twentiethcentury<br />

ava nt-garde manifestations ranging from<br />

LEF and constructivism to Dada (though Fluxus<br />

people were not linked to the anarchistic and<br />

des tructive ethos ofDada).<br />

Perhaps the best short definition of Fluxus<br />

is an elegant little manifesto that Dick Higgins<br />

published in 1966 as a rubber stamp:<br />

Flux us is not:<br />

-a moment in history or<br />

-an art movement.<br />

Flux us is:<br />

-a way of doing things,<br />

- a tradition, and<br />

-a way oflife and death.B<br />

These words summarize the time-bound,<br />

transformational, and interactive development<br />

of Flu x us. In the late 1970s, I suggested using<br />

content analysis of Flux us projects to give an<br />

overview of Fluxus, and in 1981, Peter Frank<br />

and I used this method to chart the participants<br />

for a history of Fluxus 9 In 1991, James Lewes<br />

brought our chart forward in time by surveying<br />

twenty-one Flux us exhibitions, catalogues, and<br />

books. The resulting chart offers an overview of<br />

the "who was who (and where)" ofFluxus over a<br />

thirty-year period. 10<br />

The study suggested a consensus of opinion<br />

about the allegiance of those whose names<br />

appea red in more than half of th e compilations<br />

as a key participant in Fluxus. There were thirtythree<br />

artists on this list: Eric Andersen, Ay-0 ,<br />

Joseph Beuys, George Brecht, Philip Corner, Jea n<br />

Dupuy, Robert Filliou, Albert Fine, Ken Friedman,<br />

Al H ansen, Geoffrey H endricks, Dick Higgins,<br />

Joe Jones, Milan Kniza k, Alison Knowles,<br />

Addi K0pcke, Takehisa Kosugi, Shigeko Kubota,<br />

George M aciunas, Larry Miller, Yoko Ono,<br />

N am June Paik, Benjamin Patterson, Takaka<br />

Saito, Tomas Schmit, Mieko Shiomi, Daniel<br />

Spoerri, Ben Vautier, Wolf Vostell , Yoshimasa<br />

Wada, Robert Watts, Emmett Williams, and La<br />

Monte Young. These thirty-three individuals are<br />

included in the majority of projects and exhibitions,<br />

but a broad vision of the Flu x us community<br />

would include m any more, among others<br />

Don Boyd, Giuseppe Chiari, Esther Ferrer, Juan<br />

Hidalgo, D av i det Hampson, Alice Hutchin ,<br />

Bengt af Klintberg, Carla Liss, Jackson M ac<br />

Low, Walter Marchetti, Richard M axfield, Jonas<br />

M ekas, Carolee Schneem ann, Greg Sharits, and<br />

Paul Sharits.<br />

In 1982, Dick Higgins wrote an essay in<br />

w hich he attempted to id e11 tify nine criteria<br />

th at di stinguished, or indicated the qualities of,<br />

Fluxus: internationalism, experimentalism and<br />

iconoclasm , intermedia, minimalism or concentration,<br />

an attempted resolution of the art/<br />

life dichotomy, implicativeness, play or gags,<br />

ephemerality, and specificity. Later on I worked<br />

with Dick's list, expanding it to twelve criteria:<br />

globalism, the unity of art and life, intermedi a,<br />

experimentalism , chance, playfulness, simplicity,<br />

implicativeness, exemplativism , specificity,<br />

presence in time, and musicality. 11 While Flu xus<br />

had neither an explicit re ea rch program nor a<br />

common conceptual program, a range of reasonable<br />

issues could be labeled id eas, points of<br />

commonality, or conceptual criteriaY If they do<br />

36 Fluxus .1nd the E~semi.1l Qut'\tJom nfLJtt•

not constitute the framework of an experimental<br />

research program, they do make a useful framework<br />

for a laboratory of ideas.<br />

In some respects, the Flu xus community<br />

functioned as an invisible college, not unlike the<br />

community that would give rise to early modern<br />

science. 13 The first invisible colleges involved<br />

"groups of elite, mutually interacting, and productive<br />

scientists from geographically distant<br />

affiliates who exchange[d] information to monitor<br />

progress in their fi eld [ s] ." 14 In a different way,<br />

Fluxus fulfilled many of the sa me functions, and<br />

several Flu xus people identified their work-and<br />

Flux us-as a form of research. 15<br />

D espite the parallels, though, there are also<br />

major differences, particularly in the respective<br />

attitudes of the two groups toward experiment,<br />

and in the debate surrounding what each group<br />

lea rned from or developed through experimental<br />

work. The natural philosophers whose<br />

efforts gave rise to modern science developed<br />

an agreed-upon language and method of formal<br />

experiment, while the artists and composers<br />

in Fluxus ex peri men ted informally and hardly<br />

agreed on anything. Formal experiment often<br />

seeks to answer clea rly identified ques tions; artisti<br />

c experiment usually seeks informal, playful<br />

results that are cast as emergent discoveries only<br />

in retrospect. Finally, beginning with the earliest<br />

journals-the Journal des Scavans (1665-1792)<br />

and Philosophical Transactions (1665-present)<br />

natural philosophers and scientists used articles,<br />

monographs, and other media, along with public<br />

debates and programs of experiments, as platforms<br />

for exchanging ideas and debating results,<br />

producing in the process a robust, progressive<br />

dialogue. Flux us never developed such robust<br />

mechani m s. 16<br />

What does make the comparison with the<br />

invisible college appropriate is that hardly anyone<br />

in Fluxus was part of a formal institution. What<br />

we shared were common interests and reasonably<br />

regular meetings, both personal and virtual.<br />

M embers of th e Flux us community created a<br />

rich informal information sys tem of newsletters,<br />

multiples, publications, and personal correspondence<br />

that enabled continual communication<br />

among colleagues who might not meet in per on<br />

for years at a time. There were only one or two<br />

large-scale events that ga thered the entire community<br />

in one place. 17 N evertheless, subsets and<br />

constellations among Flux us participants have<br />

been meeting in a rich cycle of concerts and<br />

festivals that began in 1962 and have continued<br />

sporadically for much of the half century since<br />

then. All of this created a community that fits<br />

the description of an invisible college in many<br />

respects.<br />

The idea of Flux us as a laboratory, on the<br />

other hand, goes back to America n pragmatism<br />

and its predecessors, Unitarianism and America n<br />

transcendentalism , as well as to the Shakers. 1 R<br />

The Unitarians descended from the Congregational<br />

churches of N ew England. These were<br />

Puritan Calvinist churche , but Puritanism took<br />

a radical turn in the theology of William Ellery<br />

Channing. In the ea rly 1800s, Channing turned<br />

away from the doctrine of si n and punishment,<br />

as well as the doctrine of the Trinity, to establish<br />

w hat became Unitarian C hristianity. 19 Channing<br />

influenced Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry<br />

D avid Thoreau, and the other transcendentalists,<br />

several of whom sought ways to build a world<br />

of action in daily life through communities that<br />

embraced new concepts ofwork. 20 Among Europea<br />

n thinkers of interest to the transcendentalists<br />

were Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whose term<br />

" intermedia" would reappea r in Fluxus (though<br />

with a different meaning), and Friedrich Schleiermacher,<br />

whose work on Biblical criticism and<br />

hermeneutics (the art of interpretation) paved the<br />

way for a new concept of interpretation theory.<br />

Emerson foreshadowed both Cage and<br />

Fluxus by introducing the concept of the ordinary<br />

into American philosophy and art. H e was<br />

one of the first Americans to write about Asian<br />

religion and philosophy as well-another link to<br />

Cage and to Fluxus artists, many of whom shared<br />

an interest in Asian philosophy, especially Z en<br />

Buddhism . In contrast to the European concept<br />

Fluxus: A <strong>Laboratory</strong> of <strong>Ideas</strong> 37

of the sublime, which was a distinctly different<br />

view of culture, Emerson emphasized the present<br />

moment and the commonplace. In his essay titled<br />

"Experience," Emerson writes, ' I ask not for the<br />

great, the remote, the romantic ... I embrace<br />

the common, I explore and sit at the feet of the<br />

familiar, the low. Give me insight into today, and<br />

you may have the antique and future worlds."<br />

His embrace of the quotidian even turns rhetorical:<br />

"What would we reall y know the meaning<br />

of? The meal in the firkin; the milk in the pan;<br />

the ballad in the street; the news of the boat; the<br />

glance of the eye; the form and ga it of the body." 21<br />

Like Emerso n and his close friend H enry David<br />

Thoreau, Flu xus artist Dick Higgins would also<br />

celebrate the near, the dow n-to-earth, the fa miliar,<br />

in his "Something Else M anifesto" and "A<br />

C hild 's History of Flux us." 22<br />

Transcendentalism's emphasis on experience<br />

as th e basis for philosophy evolved into pragmatism<br />

toward the end of the 1800s in N ew England.<br />

John D ewey, George H erbert M ead, and<br />

C harles Sanders Peirce were born in N ew England,<br />

and William James spent much of his life<br />

there. R elated to the Puritan Calvinist tradition<br />

through Congregationalism and transcendentalism,<br />

23 these men ultimately developed a<br />

concrete philoso phy for the New W orld . M ead 's<br />

contribution to social thought through symbolic<br />

interac tionism provides a rich framework<br />

for understanding Flu xus. The idea behind w hat<br />

George M aciunas labeled " functionalist" art was<br />

not functionalism as we understand it today but a<br />

complex paradigm of sy mbolic functions. 24<br />

The transcendentalist concern for the significa<br />

nce of everyday life manifested itself in the form<br />

of utopian communities such as Brook Farm, but<br />

this was not the first such effort, nor would it be<br />

the las t. The so-called "Eightfold Path" of Buddhism-right<br />

view, right intention, right speech,<br />

right discipline, right livelihood, right effort,<br />

right mindfulness, right concentration-embodies<br />

similar concepts of common work. 25 George<br />

M aciunas's grea t, unrealized vision of Fluxus<br />

was to establish such a community, an idea he<br />

pursued in the Fluxhouses and several other ventures.<br />

M aciunas was never able to rea li ze this<br />

fully, but his ideas did give rise to a number of<br />

workable projects.U'<br />

George's las t attempt at building a utopian<br />

community took place in N ew M arlborough,<br />

Massachusetts, w here he moved in order to be<br />

close to Jean Brown's Fluxus collection and<br />

archive in an old Shaker seed house in Tyringham<br />

, M assachusettsY This part of the United<br />

States had a tradition of utopian communities,<br />

from the revolutionary period, to the America<br />

n renaissance sparked by Emerson, Thoreau,<br />

and the transcendentalists, to Shaker se ttlements.<br />

Things had not changed all that much w hen Jea n<br />

se t up shop a little ways down the road from a<br />

half a dozen communes . 2 H<br />

The Shakers were among the first productive<br />

utopians of the modern era. They were a religious<br />

community to be sure, but their religion<br />

was one of service. They established some of the<br />

first m ass production industries in the world,<br />

selling obj ects and arti fac ts through catalogues.<br />

Their furniture, superb in design and perfect in<br />

balance, was the first example of industrial design<br />

and ergonomic sensibility in the furniture trade.<br />

And they supplied America's farms and gardens<br />

with top quality seed.<br />

A seed house was a building where seeds<br />

were sorted and packaged. 'The packages could<br />

be ordered individually by ca talogue or m ail<br />

order, in much the sa me way M aciunas would<br />

market Flux-products. There were also seed kits<br />

with an assortment of packages in tidy boxes that<br />

were not too different in shape or size from the<br />

suitcase-sized Fluxkits of the 1960s. Like the<br />

Flu xkits, only a few remain. In an interesting<br />

coincidence, the most complete extant seed kit<br />

is to be found at Enfield Shaker Village, 29 close<br />

to H anover, N ew Hampshire, where the Hood<br />

Museum of Art at Dartmouth College houses a<br />

Flu xus collection established in honor of George<br />

M aciunas.<br />

Like George, the Shakers were abstemious<br />

and celibate, and there were other delightful<br />

38 Fluxus ,md lilt I ~'l'llll d t~dc t1un ut il'c'

similarities as well. The Shaker umon of work<br />

and life included art and music as more than mere<br />

pastimes. A sense of industry and a light spirit<br />

were central characteristics of the Shaker community,<br />

qualities that also typified the Fluxus<br />

community at its be t. The Shakers organized<br />

their communal life around two functi ons, work<br />

and worship, and the productive Shaker economy<br />

was a distinctive attribute of their villages. 311<br />

R eading the rules of the order, it is nea rly impossible<br />

to sepa rate work from other aspects ofShaker<br />

life, with risi ng and returning to bed, meals, and<br />

even household management structured around<br />

the tempo and meaning of the working life. 3 1<br />

When I fmt met Dick Higgins in 1966, I<br />

caught from his ideas a vision of work as part<br />

of exactly that kind of community life. Dick's<br />

"Something Else M anifesto" called for artists<br />

to "chase down an art that clucks and fills our<br />

guts." 32 This was a call to collaboration and a call<br />

to productive work, to art as a kind of production<br />

that engages the concept of community.<br />

Dick would introduce me to George M aciunas,<br />

w hose philosophy of Fluxus articulated many of<br />

the same principles. George's vision of Fluxus<br />

called for artists w ho were w illing to create work<br />

together, sharing ideas and principles, supporting<br />

one another. While George's vision ofFlu x us<br />

was intensely political at one point in his life, by<br />

the time I met him he had shifted from a strictl y<br />

hierarchical concept of the collective to a vision<br />

that was much more open.<br />

H ow did Flux us so readil y become this collaborative<br />

working community or laboratory of<br />

ideas and practices? For one thing, most of the<br />

Fluxus artists were already collaborating in one<br />

way or another; Fluxus simply became a new<br />

point of intersection for usY Some of the artists<br />

already knew one another, and others had<br />

worked together for many years, such as those<br />

in the N ew York Audio-Visual Group and John<br />

Cage's former students. They did not come to<br />

Fluxus, Flux us came to them w hen George<br />

M aciunas crea ted the name for a magazine that<br />

would publish their work. This was a building<br />

already under construction when Maciunas came<br />

along and named it Fluxus.<br />

For another thing, despite the broad range<br />

of interests and w ide geographical spread, Fluxus<br />

was not that large a community-in the 1960s, it<br />

involved fewer than a hundred people in a world<br />

population of about three billion, part of a slightly<br />

larger community of several hundred people w ho<br />

were ac tive in a relatively small sector of the art<br />

world that we might label the ava nt-garde. Those<br />

w ho knew each other brought other interesting<br />

people into the group, w here they beca me interested<br />

in the same kinds of issues and undertook<br />

the sa me kind of work.<br />

History is always contingent, and there<br />

are countless scenarios in w hich certain people<br />

might never have met, or might have met without<br />

forming a community, or formed a very<br />

different kind of community. As it happened,<br />

however, the social and historical development of<br />

Fluxus generated intense correspondence among<br />

artists even at a distance, countless common<br />

projects, and many different kinds of collaboration.<br />

Flux us artists met together sporadically but<br />

relatively often, and some have worked togeth er<br />

closely for five decades now.<br />

The concept of experiment m akes claims on<br />

both thought and action. In a community such as<br />

Fluxus, these claims lead in different and occasionally<br />

contradictory directions. Such a diverse<br />

community of experimental artists, composers,<br />

and designers, who lacked a coherent resea rch<br />

program while working with a multiplicity of<br />

approaches, runs the risk of being seen as an artist<br />

group or even a movement w ith some kind<br />

of continuing connection. This is especially the<br />

case because some of the participants managed to<br />

ea rn a living making art and most were happy,<br />

or at least willing, to exhibit their products in art<br />

museums and sell it in art galleries . While Flux us<br />

was aggressively interdisciplinary, involving art,<br />

architecture, design, and music (among other<br />

things), it was never the kind of late modernist<br />

art movement to which it has often been reduced.<br />

The Dartmouth College motto is apposite<br />

Fluxus: A <strong>Laboratory</strong> of <strong>Ideas</strong> 39

here: Vox Claman.tis in Deserto, taken from the<br />

first words of Isaiah 40:3: "A voice cries, 'In the<br />

wilderness, prepare the way of the Lord. Make a<br />

straight highway for our God across the wastelands."'<br />

In this passage, the mountains are to be<br />

made flat, the rough ground level, and the rugged<br />

places a fertile plain. For George Maciunas,<br />

the way forward involved leveling and bringing<br />

an end to the art world. He felt that art was a<br />

distraction that prevented people from building a<br />

better world, while reinforcing the concepts and<br />

privileges of the upper class. George's vision of a<br />

productive world entailed erasing art, but it was<br />

a vision that tended to confuse art and the economic<br />

and social forces that surrounded it. Many<br />

Fluxus artists disagreed with his view, and even<br />

George was inconsistent-his taste in music, for<br />

example, embraced both Monteverdi and Spike<br />

Jones.<br />

Of course, many love the mountains and<br />

the rough ground as much as the highways and<br />

the plains. The dialectical demands of Fluxus<br />

also included George Brecht's proposal to think<br />

something else, Milan Knizak's call to live differently,<br />

Robert Filliou's vision of an art whose<br />

purpose is to make life more interesting than art,<br />

and Dick Higgins's metaphor of an art that clucks<br />

and fills our guts. Such an approach to art and<br />

life-to art within life-entails an experimental<br />

approach that connects in significant if sometimes<br />

amorphous ways with being-in-the-world,<br />

and that generates multiple activities of different<br />

kinds. 34<br />

The differences within Fluxus have made it<br />

difficult to frame us all as "Flux us people." Art<br />

has been a default frame, one that is only occasionally<br />

appropriate. Compressing the larger laboratory<br />

into that frame means that a great deal<br />

about Fluxus has been missed. What Fluxus was<br />

and perhaps remains is the most productive laboratory<br />

of ideas in the history of art, an invisible<br />

college whose field of study encompasses the<br />

essential questions oflife.<br />

Notes<br />

1 Harry Rube, Flu x us: The<br />

Most R adical and Experimwtal<br />

A rt Movenrent of the Six ties<br />

(Amsterdam: A. , 1979).<br />

2 In the space ava ilable here, it wi ll<br />

be impossible to provide a full<br />

account of Fluxus as a laboratory<br />

of ideas and an experimental<br />

network. This is instead an "essay"<br />

in the classical sen es of the word,<br />

as defin ed by th e Oxford English<br />

Dictio11ary: "Action or process<br />

of trying or testing," and "A<br />

composition of moderate length<br />

on . .. [a subj ect] more or less<br />

elaborate in style, though limited<br />

in range<br />

3 Several excellent accounts<br />

examine the yea rs before<br />

Fluxus emerged, including AI<br />

Hansen, Happwir·rgs : A Primer<br />

of Time-Space Art (N ew York:<br />

Something Else Press, 1965);<br />

Dick Higgins, j ifferson's Birthday /<br />

Post Fa ce (N ew York: Something<br />

Else Press, 1964); Higgins, " In<br />

einem Minnensuchboot um<br />

die W elt," in 1962 Wiesbaden<br />

FL UX US 1982 (Wiesbaden and<br />

Berlin: H arlekin Art and Berliner<br />

Kunstlerprogramm des DAAD,<br />

1982), 126-35 (in parallel German<br />

and Eng Li sh); J erry Hopkins, Yoko<br />

Ono (New York: Mac millan),<br />

esp. 20-30; Jackson Mac Low,<br />

"Wie George Maciunas die New<br />

Yorker Avantgarde kennelernte,"<br />

in 1962 Wiesbaden FLUXUS 1982,<br />

11- 125 (in parallel German and<br />

English); O wen Smith, "Proco<br />

Fiu xus in the United States: The<br />

Establishment of a Like-Minded<br />

Community of Artists," in<br />

Fhrx us: A Concept1wl Country, ed.<br />

Estera Milman, a special issue<br />

of Visible Language, vol. 26, nos.<br />

1-2 (Providence: Rhode Island<br />

School ofDesign, 1992), 45-57;<br />

and Owen Smith, Flu x us: The

History of a11 A ttitude (San Diego:<br />

San Diego State Unive rsity Press,<br />

1998), 13-68.<br />

4 For a comprehensive history<br />

ofFluxus, see Smith, Flu x us:<br />

The History of a11 Attitude. For<br />

discussions of ea rly Flu xus, see<br />

also O wen Smith, " Developing<br />

a Fluxable Forum: Earl y<br />

Performance and Publishing,"<br />

in Th e Flu xus Reader, ed. Ken<br />

Friedman (London: Academy<br />

Press, J ohn Wiley and Sons,<br />

1998), 3-21, and Hann ah<br />

Higgins, " Flux us Fortuna," in The<br />

Flux us R eader, 31- 59. Th e Fht x us<br />

R eader also contains an extensive<br />

chronology.<br />

5 The loose but purposeful<br />

evolution ofRobert Filliou into<br />

Flu xus is relatively typica l; see<br />

Patrick Martin, " Unfinished<br />

Filliou: On the Flu xus Ethos<br />

and the Origins of R elational<br />

Aesthetics," A rt j ournal 69, nos.<br />

1-2 (Spring-Summer 2010):<br />

44-62. Bengt afKlintberg is<br />

another good story; see Ken<br />

Friedman, "The Case for Bengt<br />

afKlintberg," Perfonnance Resea rch<br />

11 , no. 2 (2006): 137-44, and<br />

Bengt afK!intberg, Svensk Fht x us<br />

(Swedish Fhtxus) (Stockholm:<br />

Rannells Antikvariat, 2006) . Dick<br />

Higgins described the Flu xus<br />

expansion process as a seri es of<br />

waves; see Higgins, Modernism<br />

since Postmodemisrn: Essays on<br />

fl·ttermedia (San Diego: San Diego<br />

State University Press, 1997), 163.<br />

6 For an explicit discussion of this<br />

issue by Fluxus co-founder Dick<br />

Higgins, see Higgins, Modemism<br />

sit"JCe Postm odemism, 161-63 and<br />

173-82. Correspondence between<br />

the artists and George M aciunas,<br />

as well as correspondence among<br />

the artists themselves, contain s<br />

explicit refusals to sign any<br />

proposed manifesto as well as<br />

opposition to the very notion of<br />

a common ideology. (There are<br />

many exampl es in the Archi v<br />

Sohm in Staa tsga leri e Stuttga rt<br />

and the j ea n Brown Archive at<br />

the Getty R esearch Institute.) A<br />

recent conference titled Alternative<br />

Practices i11 Desig 11 : The Collective:<br />

Past, Present, a11d Future at RMIT<br />

University in Melbourne explored<br />

the multiple dimensions of the<br />

idea of the collecti ve. In th e 1960s,<br />

the word was closely lin ked to the<br />

Soviet notion of collecti ve farms<br />

and forced industrial collecti ves,<br />

which probably influenced<br />

George Maciunas's view at some<br />

point; certainly governance by<br />

an unelected commissar was one<br />

reason that most Flu xus artists<br />

shied away from the idea. After<br />

the Melbourne conference,<br />

however, my own view on aU of<br />

this changed, and l have come to<br />

feel that more recent models of<br />

collecti ve community and ac tion<br />

might usefully describe th e Fluxus<br />

ph enomenon.<br />

7 See Ellsworth Snyder, "John Cage<br />

Discus es Flu xus," in Fht xus: A<br />

Co nceptual Co u11try, 59-68. For<br />

an enlightening exa mination<br />

of Flu xus and Z en, ee D avid<br />

T. D ori s, " Z en Vaudeville: A<br />

M edi (t)a tion in th e Margins of<br />

Fluxus," in Th e Fht xus R eader,<br />

237-53.<br />

8 Higgins, Modemism since<br />

Postrn odemistn, 160.<br />

9 Ken Friedman and Peter Frank,<br />

" Fiu xus," in A rt Vivant: Special<br />

Report-Fhtxus 11 (Tokyo: N ew<br />

Art Seibu Company, Ltd., 1983),<br />

and Ken Friedman w ith Peter<br />

Frank, " Flu xus: A Post-Definitive<br />

History: Art Where R esponse Is<br />

the H eart of the Matter," High<br />

Perfo rm ance 27 (1984): 56- 61, 83.<br />

10 Ken Friedman w ith James Lewes,<br />

" Flux us: Global Com.mun it y,<br />

Human Dimensions," in Fht xus:<br />

A Concept11al Co t.tt·ttry, 154- 79.<br />

The completed chart offers a<br />

broad consensus of opinion by<br />

thirty experts who have given<br />

lengthy co nsideration to Flu xus,<br />

including scholars, critics,<br />

curators, ga llerists, art dea lers,<br />

Flu xus artists, and other artists<br />

interested in Flu xus. A !together,<br />

the chart includes 351 artists<br />

presented in twenty-one different<br />

projects representing a wide<br />

va riety of ve nues, prese ntati on ,<br />

and publica tions during the<br />

thirty years of Flu xus up to<br />

1992.<br />

11 Dick Higgins, " Fiu xus: Theory<br />

and R eception," L1.111d Art Press,<br />

Fluxus R esea rch issue, vo l. 2, no.<br />

2 (1991): 33. Dick's first ve rsion<br />

of the nine criteria appea red<br />

in a privately published 1982<br />

paper titled " Flu xus T heory and<br />

R eception," which was reprinted<br />

in 1998 in Tlte Fluxt.ts R eader,<br />

217-36. Dick expanded his li st to<br />

eleven in Higgins, Modentism si11 ce<br />

Postm odemism, 174-75. For my<br />

amended li t, see Ken Friedman,<br />

Flu xps aud Co mpauy (N ew York:<br />

Emily Harvey Gallery, 1989), 4,<br />

reprinted in Achille Bonito Oliva,<br />

Gino DiMaggio, and Gianni<br />

Sassi, eds., Ubi Fluxus, ibi motus<br />

1990-1962 (Veni ce and Milan: La<br />

Biennale di Venezi a and Mazzotta<br />

Editore, 1990), 328-32. A later<br />

version of Flu x us and Company<br />

appea red in The Fhtx t.ts R eader as<br />

well, 237-53.<br />

12 Dick and I discussed these ideas<br />

extensively over the yea rs, and at<br />

different times Dick labeled them<br />

criteria or points. In Modernism<br />

sirtce Pos t111odemism, he used th e<br />

term " points" but added, " rea lly,<br />

they are alnwst criteria" (175).<br />

Fluxus: A <strong>Laboratory</strong> of <strong>Ideas</strong> 41

13 For more o n th e concept of the<br />

invisible college, see Diana C rane,<br />

luvisible Colleges: D iffusiou

20 For more on transcendentalism,<br />

see J oel Myerson, Tir e Tmrrsce/1-<br />

deura/isrs: A R evier// of R esearch 1111d<br />

Criticis 111 (New Yo rk : Modern<br />

Language Association of America,<br />

1984), and Myerson, ed., Trarr scerrdcutalislll:<br />

A Reader (N ew York :<br />

Oxford University Press, 2000).<br />

21 R alph Waldo Emerson, Essays aud<br />

Lectures (New York: The Library<br />

of America , 1983 [1 837J), 68-69.<br />

Thanks to Dine Fri edman for<br />

directing me to these passages.<br />

22 The "Something Else Man ifesto"<br />

was published in 1964 in Mauifestoes<br />

(N ew York: Something Else<br />

Press), 21 (digital reprint avai l<br />

able from UbuWeb at http://<br />

www.ubu.com / h istorica 1/ gb/<br />

index.html). "A Child's History<br />

ofFiuxus" was published in 1979<br />

in C harlton Burch's Liglrrworks<br />

magazine and reprinted in Dick<br />

Higgins, Horizous: Tir e Poetics aud<br />

Theory of tire lrrtenuedia (Carbondale:<br />

Southern lllinois Universi ty<br />

Press, 1984).<br />

23 That is to ay, not alvinist<br />

dogma but rather Jonathan<br />

Edwards's mystica l "divine and<br />

supernarurallight" imparted to<br />

the soul from God.<br />

24 See George Herbert Mead, Mi11d,<br />

Se[f, aud Society fro ru tire f(/1/dpoiur<br />

of a Social Belraviorisr, ed. and<br />

intro. Charles Morris (Chicago:<br />

University of Chicago Press, 1967<br />

[1 934]) , and Herbert Blumer,<br />

Sy111bolic luteracriouis111: Perspecti11e<br />

aud Met/rod (Berkeley: University<br />

ofCalifornia Press, 1986) , esp.<br />

1-60 on methodology and 61-77<br />

on M ea d 's thought. 1 discovered<br />

Mead 's work in 1965 and Blumer's<br />

in th e early 1970s and have<br />

relied heavily on both in the<br />

decades ince. The fir t doctoral<br />

dissertation to examine Flu xus<br />

was by anthropologist Marilyn<br />

Ekdahl Ravicz, who developed<br />

her perspective based on Dewey's<br />

pragm atism. Titled "Aesthetic<br />

Anthropology: Theory and<br />

Analysis of Pop and Concepwal<br />

Art in America," she completed<br />

it in 1974 for the Department of<br />

Anthropology of the University of<br />

California at Los Angeles.<br />

25 One of the genuine puzzles l<br />

contend with in considering<br />

Fluxus and o ther art (or "anarr")<br />

communities that acknowledge<br />

Buddhism a a o urce has been<br />

the general lack of interest in<br />

ethics. lt is difficult to conceive of<br />

Buddhism , either Zen or the other<br />

schools, without th e foundational<br />

ethics of the Eightfold Path .<br />

26 For an exceLlent di sc ussion of<br />

George Maciunas's experiment<br />

in urban development and th e<br />

Fluxhouses, see C harl es R .<br />

Simpson, "The Achievement of<br />

Territorial Community," in SoHo:<br />

Tire Artisr i11 rlre Ciry (Chicago:<br />

The University of C hicago Press,<br />

1981), 153-88. In 2008, Stendhal<br />

Gallery in New York organized<br />

an exhibition titl ed C eor:ge<br />

Machuras: Prifabricated Buildiug<br />

Sysrern that examined Maciunas's<br />

architectllral ideas . The Simpson<br />

chapter is available on the gallery's<br />

website, along with excellent<br />

essays by Julia R obinson, Carolina<br />

Carrasco, M ari Dumett, and<br />

others. The ga llery URL is<br />

http://stendhalgallery.com, and<br />

the essays are ava ilable at http://<br />

stendhalga ll ery.com / ?page_<br />

id=852 (accessed Au gust 19,<br />

2010).<br />

27 A sensitive portrait of George's<br />

last community appears in a book<br />

by his widow: Billie Maciunas,<br />

Tir e Eve of Flux us: A F/u x /1/ e/ll oir,<br />

w ith a preface by Kri stine Stiles,<br />

an introduction by Geoffrey<br />

Hendricks, and an afterword by<br />

Larry Mi ller (Orlando, Florida:<br />

Arbiter Press, 2010). The J ea n<br />

Brown Archi ve is now part of<br />

the Getty Center for the Arts<br />

and Humanities in Los Angeles,<br />

alifornia. Its UR.L is http://<br />

www.getty.edu / research/. The<br />

online catalogue and findings aids<br />

describe the collection.<br />

28 I spent the summer of 1972 in<br />

Tyringham working with Jea n<br />

Brown and helped arrange the firSt<br />

meeting between Jea n and George<br />

M aciunas. I knew th ey would hit<br />

it off but never imagined how<br />

rich their relationship would<br />

become. It delighted me th at<br />

Jea n's archi ve was located in an<br />

old Shaker seed hou e in the<br />

Berkshires of Massachusetts. Every<br />

evening when we ate dinner<br />

together, J ea n would quote the<br />

old Shaker proverb, " Hands to<br />

work and hea rts to God." It is<br />

fitting th at Ameri ca's first great<br />

Flu x us collection was established<br />

in a Shaker seed ho use, while<br />

George's last Fluxus cooperative<br />

housi ng project was based nea rby<br />

in the wooded hea rtland of<br />

tra nscendenta I ism.<br />

29 Information on th e Enfield Shaker<br />

Museum is available at http://<br />

www.shakermuseum.org/ index.<br />

html.<br />

30 See Edward Deming Andrews,<br />

Tir e People Ca lled Shakers (Oxford :<br />

Oxford University Press, 1953),<br />

94- 135.<br />

31 Ibid ., 253-89.<br />

32 Dick Higgins, "A Something<br />

Else Manifesto," in Man ifestoes,<br />

21. Digital reprint ava ilable from<br />

UbuWeb at http://www.ubu.<br />

com/ h isrorica 1/ gb/ index. html.<br />

33 This includes even people like<br />

me, w ho were not artists before<br />

we became in volved w ith the<br />

artists and composers in Flu x us.<br />

For the story of how a would-be<br />

minister became an artist-or,<br />

in M arcel Duchamp's terms, an<br />

F!Jxus. A <strong>Laboratory</strong> of <strong>Ideas</strong> 43

"anartist"- see Ken Friednun,<br />

"Events and the Exquisite<br />

Corpse," in Tl1 e Exq11isire<br />

Corpse: Cha11ce and Collaborarion<br />

in S11rrealis111's Parlor Ga111e, ed.<br />

Kanta Kochhar-Lindgren,<br />

Davis Schneiderman, and Tom<br />

Denlinger (Lincoln: University<br />

of N ebraska Press, 2009), 73-74,<br />

fn. 6, as well as Peter Frank, "Ken<br />

Friedman : A Life in Fluxus,"<br />

in Artistic Berljellows: Hisrories,<br />

Theories and Conversations in<br />

Collaborative Art Practices, ed. Holly<br />

C rawford (Lanham: University<br />

Press of America, 2008), 145-86.<br />

34 Curatorial analysis in general<br />

has tended to dismiss Flux us's<br />

engagem ent with the larger world<br />

by portray ing its experiments<br />

and failures as ineffective. For<br />

example, in Thomas Kellein's<br />

2007 book George Mach111as and th e<br />

Dream of Fhi XIIS (London: Thames<br />

and Hudson), George is depicted<br />

as a brilliant but failed dreamer.<br />

It is certainly true that we often<br />

influenced social change without<br />

influencin g the formal qualities or<br />

conceptual fo cus of the trends and<br />

iss ues that we helped to create.<br />

Fluxus W es t, for example, was<br />

one of th e six or seven founding<br />

publishers of the Underground<br />

Press Syndicate in 1967, but we<br />

never gained any traction on the<br />

way th e papers were designed or<br />

what they dealt with. Even though<br />

we ca n be found in the first lists<br />

of founding papers, along w ith<br />

the Easr Village Other, the Berkeley<br />

Barb, and th e Los Angeles Free Press,<br />

we vanish from history soon after<br />

because our focus was so vastly<br />

different. Did we exert a role<br />

in developing the concept of an<br />

alternate press' Yes. Did we have<br />

any real part in the way the press<br />

developed? Perhaps we did, at least<br />

in a small way. Did we succeed<br />

in directing serious attention to<br />

cultural issues beyond the standard<br />

underground press fo ca l points of<br />

rock music, drugs, sex, and new<br />

left politics? Not hardly.<br />

44 Fluxus ,\lld thl' Es'L'Iltl.ti Qul'\tioth ofltlt: