The Korean Wave 2006 - Korean Cultural Service

The Korean Wave 2006 - Korean Cultural Service

The Korean Wave 2006 - Korean Cultural Service

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> New York Times style magazine, sunday, march 19, <strong>2006</strong><br />

134<br />

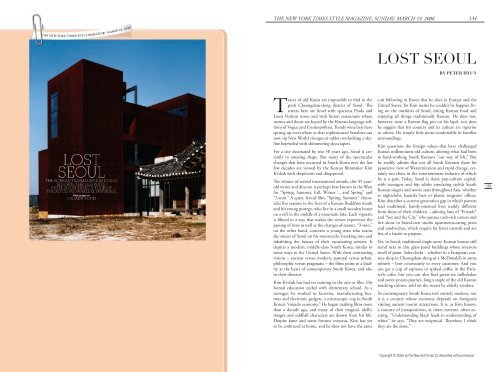

Lost Seoul<br />

By PETER HYUN<br />

Traces of old Korea are impossible to find in the<br />

posh Cheongdam-dong district of Seoul. <strong>The</strong><br />

streets here are lined with spacious Prada and<br />

Louis Vuitton stores and with fusion restaurants whose<br />

menus and decor are hyped by the <strong>Korean</strong>-language editions<br />

of Vogue and Cosmopolitan. Trendy wine bars have<br />

sprung up everywhere so that sophisticated Seoulites can<br />

now sip New World vintages at tables overlooking a skyline<br />

bejeweled with shimmering skyscrapers.<br />

For a city decimated by war 50 years ago, Seoul is certainly<br />

in amazing shape. But many of the spectacular<br />

changes that have occurred in South Korea over the last<br />

few decades are viewed by the <strong>Korean</strong> filmmaker Kim<br />

Ki-duk with skepticism and disapproval.<br />

<strong>The</strong> winner of several international awards, this 45-yearold<br />

writer and director is perhaps best known in the West<br />

for “Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter ... and Spring” and<br />

“3-iron.” A quiet, lyrical film, “Spring, Summer” chronicles<br />

five seasons in the lives of a <strong>Korean</strong> Buddhist monk<br />

and his young protege, who live in a small wooden house<br />

on a raft in the middle of a mountain lake. Each vignette<br />

is filmed in a way that makes the viewer experience the<br />

passing of time as well as the changes of season. “3-iron,”<br />

on the other hand, concerns a young man who roams<br />

the streets of Seoul on his motorcycle, breaking into and<br />

inhabiting the houses of their vacationing owners. It<br />

depicts a modern, middle-class South Korea, similar in<br />

some ways to the United States. With their contrasting<br />

visions – ancient versus modern, pastoral versus urban,<br />

philosophic versus pragmatic – the films point to a duality<br />

at the heart of contemporary South Korea, and also<br />

in their director.<br />

Kim Ki-duk has had no training in the arts or film. His<br />

formal education ended with elementary school. As a<br />

teenager, he worked in factories, manufacturing buttons<br />

and electronic gadgets, a microscopic cog in South<br />

Korea’s “miracle economy.” He began making films more<br />

than a decade ago, and many of their magical, idyllic<br />

images and oddball characters are drawn from his life.<br />

Despite fame and some fortune overseas, Kim has yet<br />

to be embraced at home, and he does not have the same<br />

cult following in Korea that he does in Europe and the<br />

United States. Yet Kim insists he couldn’t be happier, living<br />

on the outskirts of Seoul, eating <strong>Korean</strong> food and<br />

enjoying all things traditionally <strong>Korean</strong>. He does not,<br />

however, wear a <strong>Korean</strong> flag pin on his lapel, nor does<br />

he suggest that his country and its culture are superior<br />

to others. He simply feels more comfortable in familiar<br />

surroundings.<br />

Kim questions the foreign values that have challenged<br />

Korea’s millenniums-old culture, altering what had been<br />

to hard-working South <strong>Korean</strong>s “our way of life.” But<br />

he readily admits that not all South <strong>Korean</strong>s share his<br />

pejorative view of Westernization and rapid change, certainly<br />

not those in the entertainment industry of which<br />

he is a part. Today, Seoul is Asia’s pop-culture capital,<br />

with teenagers and hip adults emulating stylish South<br />

<strong>Korean</strong> singers and movie stars throughout Asia, whether<br />

at nightclubs, karaoke bars or plastic surgeons’ offices.<br />

Kim describes a current generation gap in which parents<br />

lead traditional, family-oriented lives starkly different<br />

from those of their children – adoring fans of “Friends”<br />

and “Sex and the City” who pursue cash-rich careers and<br />

live alone in brand-new studio apartments,eating pizza<br />

and sandwiches, which require far fewer utensils and are<br />

less of a hassle to prepare.<br />

Yet, in Seoul, traditional single-story <strong>Korean</strong> houses still<br />

stand next to chic glass-panel buildings whose interiors<br />

smell of paint. Sales clerks – whether in a European couture<br />

shop in Cheongdam-dong or a McDonald’s in some<br />

suburb – bow courteously to every customer. And you<br />

can get a cup of espresso or spiked coffee in the Parisstyle<br />

cafes, but you can also find green-tea milkshakes<br />

and sweet-potato pastries, long a staple of the old <strong>Korean</strong><br />

snacking culture, sold on the streets by elderly vendors.<br />

So contemporary South Korea isn’t entirely modern, nor<br />

is it a country whose economy depends on foreigners<br />

visiting ancient tourist attractions. It is, as Kim knows,<br />

a country of juxtapositions, at times extreme, often exciting.<br />

“Understanding black leads to understanding of<br />

white,” he says. “<strong>The</strong>y are reciprocal. <strong>The</strong>refore, I think<br />

they are the same.”<br />

139<br />

Copyright © <strong>2006</strong> by <strong>The</strong> New York Times Co. Reprinted with permission.