College of Forestry - Oregon State University

College of Forestry - Oregon State University

College of Forestry - Oregon State University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Features<br />

Pretty but Perilous: Protecting Forests and Meadows from<br />

Weedy Interlopers<br />

O thou weed! Who art so lovely fair and smell’st so sweet that the sense aches at thee, would thou hadst ne’er<br />

been born.—William Shakespeare, Othello<br />

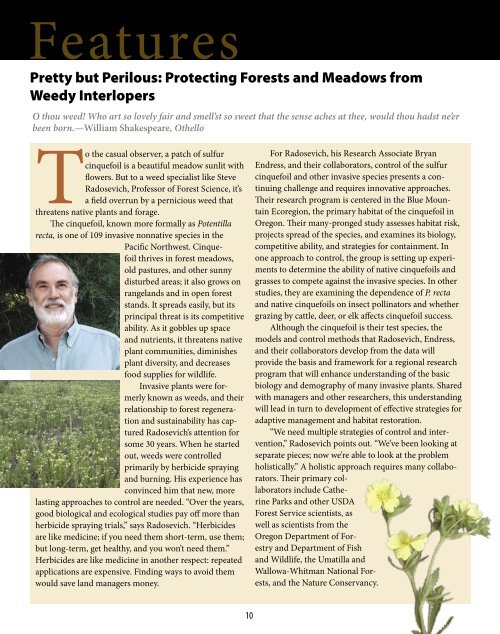

To the casual observer, a patch <strong>of</strong> sulfur<br />

cinquefoil is a beautiful meadow sunlit with<br />

flowers. But to a weed specialist like Steve<br />

Radosevich, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Forest Science, it’s<br />

a field overrun by a pernicious weed that<br />

threatens native plants and forage.<br />

The cinquefoil, known more formally as Potentilla<br />

recta, is one <strong>of</strong> 109 invasive nonnative species in the<br />

Pacific Northwest. Cinquefoil<br />

thrives in forest meadows,<br />

old pastures, and other sunny<br />

disturbed areas; it also grows on<br />

rangelands and in open forest<br />

stands. It spreads easily, but its<br />

principal threat is its competitive<br />

ability. As it gobbles up space<br />

and nutrients, it threatens native<br />

plant communities, diminishes<br />

plant diversity, and decreases<br />

food supplies for wildlife.<br />

Invasive plants were formerly<br />

known as weeds, and their<br />

relationship to forest regeneration<br />

and sustainability has captured<br />

Radosevich’s attention for<br />

some 30 years. When he started<br />

out, weeds were controlled<br />

primarily by herbicide spraying<br />

and burning. His experience has<br />

convinced him that new, more<br />

lasting approaches to control are needed. “Over the years,<br />

good biological and ecological studies pay <strong>of</strong>f more than<br />

herbicide spraying trials,” says Radosevich. “Herbicides<br />

are like medicine; if you need them short-term, use them;<br />

but long-term, get healthy, and you won’t need them.”<br />

Herbicides are like medicine in another respect: repeated<br />

applications are expensive. Finding ways to avoid them<br />

would save land managers money.<br />

For Radosevich, his Research Associate Bryan<br />

Endress, and their collaborators, control <strong>of</strong> the sulfur<br />

cinquefoil and other invasive species presents a continuing<br />

challenge and requires innovative approaches.<br />

Their research program is centered in the Blue Mountain<br />

Ecoregion, the primary habitat <strong>of</strong> the cinquefoil in<br />

<strong>Oregon</strong>. Their many-pronged study assesses habitat risk,<br />

projects spread <strong>of</strong> the species, and examines its biology,<br />

competitive ability, and strategies for containment. In<br />

one approach to control, the group is setting up experiments<br />

to determine the ability <strong>of</strong> native cinquefoils and<br />

grasses to compete against the invasive species. In other<br />

studies, they are examining the dependence <strong>of</strong> P. recta<br />

and native cinquefoils on insect pollinators and whether<br />

grazing by cattle, deer, or elk affects cinquefoil success.<br />

Although the cinquefoil is their test species, the<br />

models and control methods that Radosevich, Endress,<br />

and their collaborators develop from the data will<br />

provide the basis and framework for a regional research<br />

program that will enhance understanding <strong>of</strong> the basic<br />

biology and demography <strong>of</strong> many invasive plants. Shared<br />

with managers and other researchers, this understanding<br />

will lead in turn to development <strong>of</strong> effective strategies for<br />

adaptive management and habitat restoration.<br />

“We need multiple strategies <strong>of</strong> control and intervention,”<br />

Radosevich points out. “We’ve been looking at<br />

separate pieces; now we’re able to look at the problem<br />

holistically.” A holistic approach requires many collaborators.<br />

Their primary collaborators<br />

include Catherine<br />

Parks and other USDA<br />

Forest Service scientists, as<br />

well as scientists from the<br />

<strong>Oregon</strong> Department <strong>of</strong> <strong>Forestry</strong><br />

and Department <strong>of</strong> Fish<br />

and Wildlife, the Umatilla and<br />

Wallowa-Whitman National Forests,<br />

and the Nature Conservancy.<br />

10