OF CITIZEN WATCH - Watch Around

OF CITIZEN WATCH - Watch Around

OF CITIZEN WATCH - Watch Around

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

STORYHISTORYHIS 63<br />

THE SWISS ORIGINS<br />

<strong>OF</strong> <strong>CITIZEN</strong> <strong>WATCH</strong><br />

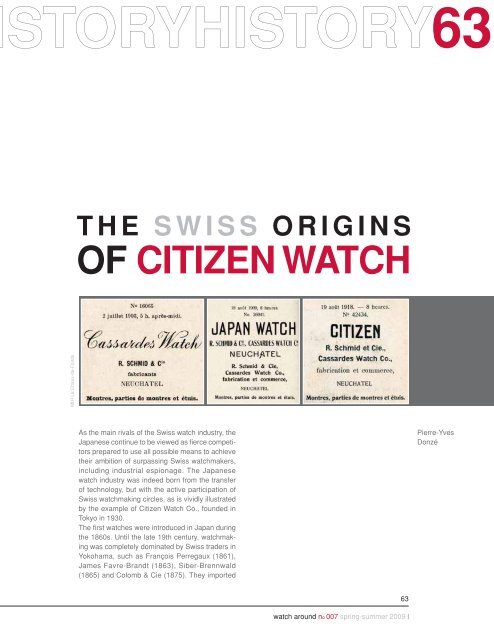

MIH La Chaux-de-Fonds<br />

As the main rivals of the Swiss watch industry, the<br />

Japanese continue to be viewed as fierce competitors<br />

prepared to use all possible means to achieve<br />

their ambition of surpassing Swiss watchmakers,<br />

including industrial espionage. The Japanese<br />

watch industry was indeed born from the transfer<br />

of technology, but with the active participation of<br />

Swiss watchmaking circles, as is vividly illustrated<br />

by the example of Citizen <strong>Watch</strong> Co., founded in<br />

Tokyo in 1930.<br />

The first watches were introduced in Japan during<br />

the 1860s. Until the late 19th century, watchmaking<br />

was completely dominated by Swiss traders in<br />

Yokohama, such as François Perregaux (1861),<br />

James Favre-Brandt (1863), Siber-Brennwald<br />

(1865) and Colomb & Cie (1875). They imported<br />

Pierre-Yves<br />

Donzé<br />

63<br />

watch around no 007 spring-summer 2009 |

HISTORYHISTORYH<br />

Photos Citizen<br />

The Citizen brand launched in 1918 by Rodolphe Schmid, who employed 200 people in his Tokyo factory by the late<br />

1920s, gave rise to the Citizen <strong>Watch</strong> Co. in 1930.<br />

Swiss watches and sold them to Japanese businessmen<br />

who handled their distribution throughout<br />

the country.<br />

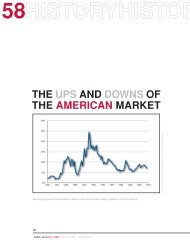

Protectionism encourages chablonnage. <strong>Watch</strong><br />

sales grew significantly with industrialisation and the<br />

development of railways : the number of units<br />

imported rose from 47,000 in 1880 to 145,000 in<br />

1900. This boom encouraged several Swiss watch<br />

merchants to seek independence from Swiss<br />

importers by producing watches themselves. It was<br />

in this context that the Seiko watch factory was set<br />

up in 1892. Its founder was a watch merchant<br />

named Kintaro Hattori, who worked with the Swiss<br />

importers in Yokohama. He succeeded in producing<br />

his own pocket-watches during the 1890s with the<br />

help of engineers trained at the watchmaking school<br />

in Le Locle and using machine tools imported from<br />

Switzerland and the United States. However, the<br />

watches made in Japan were much more expensive<br />

than their imported counterparts. To protect his own<br />

watches, Hattori, who had good political connections,<br />

instigated successive rises in Japanese customs<br />

duties. Import taxes on gold watches jumped<br />

from 5% prior to 1899 to 50% in 1906.<br />

The Swiss importers of Yokohama reacted to these<br />

protectionist policies by turning to chablonnage,<br />

which consisted of importing kits of unassembled<br />

parts that were less prohibitively taxed and then<br />

making up the watches in workshops on Japanese<br />

territory. Hattori also purchased some of these<br />

parts. Chablonnage gained considerable momentum<br />

between the two world wars. Movements<br />

accounted for 31% of the total volume of Swiss<br />

horological exports to Japan between 1900 and<br />

1915, rising to 42 % between 1915 and 1925<br />

and 81% from 1925 to 1940. This strategy was<br />

severely criticised in Switzerland because it transplanted<br />

the industry’s activities to other countries.<br />

It nevertheless remained the essential channel for<br />

the transfer of technology.<br />

Industrial transplantation causes alarm.<br />

Tavannes <strong>Watch</strong> was one of the key players in this<br />

development. Its watches were successively<br />

assembled and cased up by two small Japanese<br />

manufacturers. The first was the company founded<br />

in Tokyo in 1914 by Kono Shohei and headed by a<br />

former technical director of Hattori. It assembled<br />

Tavannes <strong>Watch</strong> kits, sold under the Pacific brand<br />

name. After this company was bought up by the<br />

Matsumura alarm clock company, the Tavannes<br />

<strong>Watch</strong> importer in Japan, Takara Trading, continued<br />

making watches from imported kits until its factory<br />

64<br />

| watch around no 007 spring-summer 2009

ISTORYHISTORYH<br />

was destroyed by fire in 1933. The activities of<br />

Tavannes <strong>Watch</strong> in Japan caused a great deal of<br />

alarm within the Swiss watch industry in the early<br />

1930s, since it seemed to have planned on setting<br />

up a movement factory there in 1932. Rolex wrote<br />

to the Federal Office for Industry, Crafts and Trades<br />

and Labour (<strong>OF</strong>IAMT), expressing strong opposition:<br />

“Once a movement factory is established in<br />

Japan by a Swiss company as large as the one in<br />

question, we can say goodbye forever to Swiss articles<br />

for the East and the Far East. After a few years<br />

these [Japanese-made] models will spread around<br />

the world.” While the statement was undoubtedly<br />

exaggerated, it certainly reflected the extreme concern<br />

aroused by industrial transplantation.<br />

Citizen’s Swiss foundations. Nonetheless, that is<br />

exactly what occurred with the development of the<br />

business of an important watch dealer who settled<br />

in Yokohama during the 1890s. Rodolphe Schmid<br />

was born in Neuchâtel in 1871, and in 1894 moved<br />

to Yokohama, where he soon asserted himself as<br />

one of the main watch merchants. By the following<br />

year, he was the city’s third largest watch importer,<br />

with more than 20,000 units. He also owned a factory<br />

in Neuchâtel, which was renamed Cassardes<br />

<strong>Watch</strong> in 1903.<br />

Directly affected by the protectionist customs<br />

duties, Schmid transferred part of his activities to<br />

Japan. He began importing kits of parts that he then<br />

had assembled in a small workshop he owned in<br />

Yokohama. In order to keep this trade supplied with<br />

components, his family created a watchcase factory,<br />

Jobin & Cie., in Neuchâtel in 1908. In 1913, a<br />

new step in the transfer process was taken with the<br />

production of cases in Japan. Schmid’s Japanese<br />

factory, which was relocated to Tokyo in 1912,<br />

enjoyed strong growth. He adopted new brand<br />

names for his watches, including Japan <strong>Watch</strong><br />

(1909) as well as Gunjin Tokei (1910), for a model<br />

intended for the army. Finally, in 1918, he opted for<br />

the Citizen brand name. His workforce grew from<br />

about 30 in 1913 to 110 in 1920, and to around 200<br />

by 1928. By then, his company was the country’s<br />

second largest watch manufacturer, behind Seiko.<br />

Schmid’s factory gave rise to the Citizen <strong>Watch</strong> Co.<br />

in 1930. This Japanese watch company was born<br />

from the merger between Schmid and the Shokosha<br />

workshop, which had been founded in Tokyo by a<br />

jeweller and aspiring watchmaker, Kamekichi<br />

Yamasaki. Financial troubles had however driven<br />

Yamasaki’s company to bankruptcy in the late<br />

1920s.<br />

Citizen <strong>Watch</strong> was founded with a share capital of<br />

200,000 yen divided into 20,000 shares. Schmid<br />

would have liked to acquire half the capital but was<br />

unable to – probably for political reasons, since foreign<br />

businessmen were encountering increasing<br />

hostility in Japan during the 1930s. Acquiring only<br />

a minor stake of 1.5%, Schmid nevertheless indirectly<br />

controlled the new company through the<br />

managers of his own factory.<br />

Principal shareholders of Citizen <strong>Watch</strong> Co., 1930<br />

Name Activity Shares (number) Shares (%)<br />

Shinji Nakajima Manager, R. Schmid & Co, Tokyo 2,449 12.2<br />

Kanamori Masutaro <strong>Watch</strong> wholesaler, Yokohama 2,200 11.0<br />

Kosaburo Nakajima – 2,125 10.6<br />

Osawa Co <strong>Watch</strong> trading company, Kyoto 1,854 9.3<br />

Kura Kawamura Employee of a watch wholesaler, Tokyo 1,045 5.2<br />

Kamekichi Yamasaki Founder of the Shokosha company, Tokyo 715 3.6<br />

Oscar Abegg Director, R. Schmid & Co, Tokyo 684 3.4<br />

Eimatsu Tsurumaki – 620 3.1<br />

Nakajima Co Trading company, Tokyo 543 2.7<br />

Kanamori Masusaburo – 543 2.7<br />

Small shareholders (100 individuals) 7222 36.2<br />

Total 20,000 100.0<br />

65<br />

watch around no 007 spring-summer 2009 |

HISTORYHISTORYH<br />

EX<br />

E<br />

Capital structure. Shareholders in Citizen <strong>Watch</strong><br />

came from two different milieus. First of all, there<br />

was a group of Schmid’s employees, headed by<br />

his marketing director, Shinji Nakajima. Born in<br />

1864, Nakajima had worked for several companies<br />

and travelled around the United States before joining<br />

Schmid in 1897. He was the first to take the<br />

reins of Citizen. Two other major shareholders,<br />

also called Nakajima and officially domiciled in<br />

Tokyo, were possibly relatives. There was also one<br />

Swiss among the shareholders, Oscar Abegg,<br />

director of the Tokyo factory and Schmid’s representative<br />

in Japan during his frequent absences<br />

from the country. The other main group of shareholders<br />

was composed of Japanese watch<br />

merchants, who invested in the company at<br />

Nakajima’s request. Osawa Co. acquired a fairly<br />

substantial stake, while four other trading companies<br />

also invested in the new firm : Nakajima,<br />

Furutani, Okasei and Izumiya Clock.<br />

Citizen <strong>Watch</strong> began operations in 1930. Initially,<br />

the Citizen workers merely assembled stocks of<br />

parts for Shokosha. But these proved hard to sell<br />

and the company ran into difficulties. Operating at<br />

a loss until 1933, it was kept alive by the Yasuda<br />

Bank. Citizen <strong>Watch</strong> also faced worker discontent,<br />

MPL<br />

A<br />

RY<br />

66<br />

| watch around no 007 spring-summer 2009

ISTORYHISTORYH<br />

The Citizen Group currently employs 18,000 people, mainly<br />

in watchmaking, electronics, machine-tools and jewellery.<br />

expressed by a strike in 1933. In the end, it was the<br />

development and marketing of wristwatches that<br />

enabled it to improve its situation, thanks to cooperation<br />

with Schmid.<br />

Technical assistance. Schmid’s involvement with<br />

Citizen was to prove essential in terms of technical<br />

assistance. He imported machine tools in 1933 and<br />

had an engineer in Geneva draw up plans for new calibres<br />

the following year. This partnership was reinforced<br />

by the Star Shokai company, which Citizen had<br />

acquired in 1932. This firm had been founded in 1926<br />

by Schmid, Nakajima and Suzuki to import Swiss<br />

Mido watches to Japan. The three wristwatches<br />

developed by Citizen up until the end of World War II<br />

(1931, 1935 and 1941) are in fact all copies of Mido<br />

products. The technical assistance provided by<br />

Schmid thus enabled Citizen to improve its position<br />

during the mid-1930s. It built a new factory in 1934<br />

and began exporting its products to China from 1936<br />

onwards. In 1939, Citizen produced almost 248,000<br />

watches, corresponding to 15% of national production.<br />

It was still far behind Hattori and its 1.3 million<br />

units, but well ahead of imported watches, which were<br />

down to fewer than 50,000 units since 1930.<br />

Rodolphe Schmid ceased his activities in Japan<br />

in the mid-1930s and returned to Switzerland,<br />

probably to Geneva, where his firm had been<br />

established as a marketing company since the<br />

1920s. He nonetheless remained firmly attached<br />

to Citizen, subscribing to the various share capital<br />

increases of the Japanese company during the<br />

war and still appearing on the 1948 list of shareholders.<br />

Technology transfer. The history of Citizen is a<br />

classic example of a watch industry born from a<br />

technology transfer process. After the war, it<br />

embarked on international expansion built on<br />

cooperation with foreign companies, including the<br />

American firm Bulova for the production of tuningfork<br />

watches (1960), the Swiss firm Méroz for<br />

watch jewels (1963), and the French firm Lip for<br />

electrical watches (1964). It also set up various<br />

production sites around the world (India, Mexico,<br />

South Korea, Hong Kong, Germany).<br />

Chablonnage not only promoted the emergence of<br />

watch companies in Japan, but also in the United<br />

States, Russia and Italy. It was an attempt to fight<br />

this new competition and to maintain production in<br />

Switzerland that led the Swiss watch industry to<br />

create a cartel in the 1930s, known as the “watchmaking<br />

statute” (statut horloger). And that will be<br />

the subject of an article in the next issue. •<br />

67<br />

watch around no 007 spring-summer 2009 |