Okanagan-Similkameen (Regional District) v ... - Rdosmaps.bc.ca

Okanagan-Similkameen (Regional District) v ... - Rdosmaps.bc.ca

Okanagan-Similkameen (Regional District) v ... - Rdosmaps.bc.ca

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

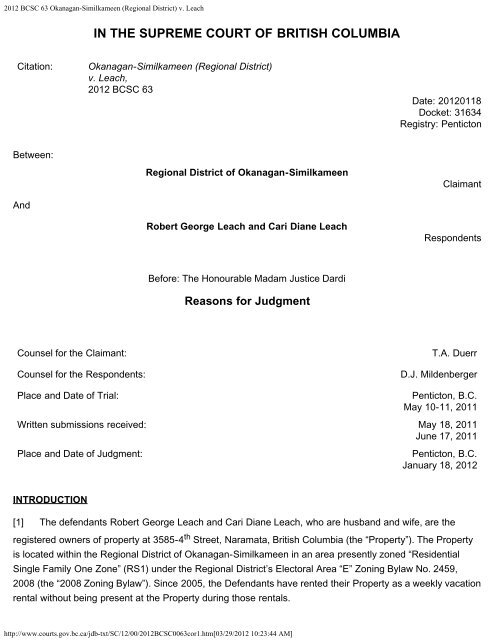

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA<br />

Citation:<br />

<strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>)<br />

v. Leach,<br />

2012 BCSC 63<br />

Date: 20120118<br />

Docket: 31634<br />

Registry: Penticton<br />

Between:<br />

And<br />

<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> of <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong><br />

Robert George Leach and Cari Diane Leach<br />

Claimant<br />

Respondents<br />

Before: The Honourable Madam Justice Dardi<br />

Reasons for Judgment<br />

Counsel for the Claimant:<br />

Counsel for the Respondents:<br />

Place and Date of Trial:<br />

T.A. Duerr<br />

D.J. Mildenberger<br />

Penticton, B.C.<br />

May 10-11, 2011<br />

Written submissions received: May 18, 2011<br />

June 17, 2011<br />

Place and Date of Judgment:<br />

Penticton, B.C.<br />

January 18, 2012<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

[1] The defendants Robert George Leach and Cari Diane Leach, who are husband and wife, are the<br />

registered owners of property at 3585-4 th Street, Naramata, British Columbia (the “Property”). The Property<br />

is lo<strong>ca</strong>ted within the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> of <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> in an area presently zoned “Residential<br />

Single Family One Zone” (RS1) under the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s Electoral Area “E” Zoning Bylaw No. 2459,<br />

2008 (the “2008 Zoning Bylaw”). Since 2005, the Defendants have rented their Property as a weekly va<strong>ca</strong>tion<br />

rental without being present at the Property during those rentals.<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

[2] The plaintiff, the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> of <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (the “<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>”), seeks a<br />

declaration that the defendants are utilizing the Property as a “commercial tourist accommodation” in<br />

contravention of the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s bylaws (the “Bylaws”); it also seeks an injunction restraining the<br />

defendants from continuing to use the Property as a va<strong>ca</strong>tion rental.<br />

[3] Pursuant to the agreement of counsel this matter proceeded by way of summary trial. The trial<br />

proceeded on affidavits, admissions made by the defendants pursuant to a Notice to Admit, and excerpts<br />

from the defendants’ discoveries read in by the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s counsel. I am satisfied that I am able to<br />

decide the issues on the evidentiary record before me and to do so would not be unjust.<br />

[4] Before turning to the analysis it is necessary to summarize the pertinent facts, to outline the positions<br />

of the parties, and to identify the key provisions of the Bylaws.<br />

FACTS<br />

[5] The essential facts are not in contention.<br />

[6] The Property is the defendants’ second home which they use as a va<strong>ca</strong>tion home. They reside at the<br />

Property one to three months each year.<br />

[7] The defendants acquired the Property in 2004, and in or about 2005, the defendants began renting out<br />

the Property, primarily on a weekly basis, for use by va<strong>ca</strong>tioners (“the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals”). The Va<strong>ca</strong>tion<br />

Rentals were advertised via a website. The website was operated by the defendant Robert Leach for the<br />

purpose of advertising the rental of the Property, providing contact information for the defendants to those<br />

interested in renting, facilitating the booking of rentals, providing schedules of dates and times available for<br />

rental and providing pictures and information regarding the Property. The defendants are the only people<br />

who have <strong>ca</strong>rried on the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals. Mr. Leach’s sister answers some <strong>ca</strong>lls from time to time, but she<br />

receives no remuneration for her services.<br />

[8] The Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals provide for weekly rental of the Property with full use of the primary dwelling<br />

lo<strong>ca</strong>ted on the Property. The Property was rented out an average of five weeks per year, primarily in the<br />

summer months, during the years of 2005 through to 2009. The defendants made the Property available for<br />

rent to one family or group ranging from two to eight people at a time. The longest period of rental to any<br />

single family was three weeks. The defendants did not operate the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals as a bed and breakfast.<br />

They were not present at the Property during the currency of the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals.<br />

[9] Zoning Bylaw No. 1566, 1995 (the “1995 Zoning Bylaw”) was the governing bylaw when the<br />

defendants began operating the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals.<br />

[10] From May to August of 2007, the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> received complaints from citizens concerning the<br />

ongoing va<strong>ca</strong>tion rental operation on the Property. On July 10, 2007, Roza Aylwin, who was then a planning<br />

technician with the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>, wrote to the defendants to advise them that their use of the Property as<br />

a tourist accommodation business was contrary to the appli<strong>ca</strong>ble zoning bylaws.<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

[11] On September 7, 2007, the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> demanded that the defendants cease the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion<br />

Rentals and the advertising associated with those rentals.<br />

[12] On November 15, 2007, the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> repealed the 1995 Zoning Bylaw and replaced it with the<br />

<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s Electoral Area “E” Zoning Bylaw No. 2373, 2006 (the “2006 Zoning Bylaw”).<br />

[13] On December 20, 2007, the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s counsel sent the defendants a letter demanding that<br />

they immediately bring to an end all va<strong>ca</strong>tion rental use and related advertising. The letter requested that the<br />

defendants confirm they had done so within 21 days, failing which enforcement proceedings would occur<br />

without further notice.<br />

[14] The defendants continued to operate the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals on an intermittent basis from 2006 through<br />

to 2009.<br />

[15] On July 4, 2008, the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> received another complaint regarding the use of the Property as<br />

a tourist accommodation.<br />

[16] On November 6, 2008, the 2006 Zoning Bylaw was repealed and replaced with Zoning Bylaw No.<br />

2459, 2008 (the “2008 Zoning Bylaw”).<br />

[17] The defendants commenced renovations to the Property in 2009. As a result of the renovations which<br />

<strong>ca</strong>rried on into 2010, the Defendants did not rent the Property in 2010. The defendant Mr. Leach deposed<br />

that:<br />

ISSUES<br />

I had many inquiries about rentals and had to defer the requests to 2011 as the renovation timeline<br />

dragged on longer than I expected. Part of this delay was due to the fact that I was <strong>ca</strong>rrying out most<br />

of the work on my own.<br />

[18] The heart of this dispute is whether or not the defendants are in breach of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw and,<br />

if so, whether they <strong>ca</strong>n rely on the defence of lawful non-conforming use.<br />

[19] I will analyze the issues under the following headings:<br />

(1) Has there been a breach of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw<br />

(2) If yes, <strong>ca</strong>n the defendants rely on the defence of lawful non-conforming use This turns on:<br />

Whether the Defendants’ use of the Property was “lawful” under the 1995 Zoning Bylaw which<br />

governed at the time the use began; and<br />

Whether the defendants have continued their use within the meaning of s. 911 of the Lo<strong>ca</strong>l<br />

Government Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 323 (the “LGA”).<br />

POSITION OF THE PARTIES<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

Plaintiff’s Position<br />

[20] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s overarching submission is that the use of the Property to provide short-term<br />

va<strong>ca</strong>tion rentals without the defendants being present is prohibited by each of the 1995, 2006, and 2008<br />

Zoning Bylaws. It seeks a declaration that the defendants are utilizing the Property as a “commercial tourist<br />

accommodation”.<br />

[21] In developing its primary contention, the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> argues that the defendants’ operation of their<br />

tourist accommodation business contravenes each of the three Zoning Bylaws be<strong>ca</strong>use the rental does not<br />

fit within the prescribed list of permitted uses under the RS1 Zoning. It asserts that the rental of the property<br />

contravenes the use as a “single-family dwelling” (within the meaning of the 1995 Zoning Bylaw) or as a<br />

“single detached dwelling” (within the meaning of the 2006 and 2008 Zoning Bylaws (the “2006/2008 Zoning<br />

Bylaws”)).<br />

[22] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> says that to allow persons to provide temporary accommodation with a singlefamily<br />

or single detached dwelling would render the Bylaws ineffectual or superfluous.<br />

Defendants’ Position<br />

[23] As a general posture the defendants assert that the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s position is not supported on a<br />

proper interpretation of the Bylaws. The defendants argue that:<br />

(a) the 2008 Zoning Bylaw does not prohibit the defendants’ use. The defendants assert that their<br />

use, which includes short-term rentals, falls within the permitted principal use in the 2008 Zoning<br />

Bylaw as a “single detached dwelling” - the defendants, their guests and renters all use the<br />

dwelling unit for living and sleeping purposes;<br />

(b) alternatively it is a permitted secondary use as “private visitor accommodation”; and<br />

(c) the 1995 Zoning Bylaw did not prohibit the defendants’ use and consequently their use currently<br />

qualifies under s. 911 of the LGA as a lawful non-conforming use.<br />

[24] The defendants challenge the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s characterization of their use as a “commercial tourist<br />

accommodation”. They point out that there is no reference to the phrase “commercial tourist accommodation”<br />

in any of the Bylaws.<br />

[25] The defendants note that short-term rentals have always been common in residential neighbourhoods<br />

in Naramata. They do not dispute, however, that the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> is not required to enforce every breach<br />

of every bylaw. Its failure to prosecute a large number of violations of a particular bylaw does not invalidate a<br />

prosecution of a violation of that bylaw: Coquitlam (City) v. Aweryn, 2000 BCSC 777 at para. 13, aff’d 2001<br />

BCCA 373, citing with approval Burnaby (City) v. Pocrnic (1999), 6 M.P.L.R. (3d) 250 (B.C.C.A.) and Polai v.<br />

Toronto (City), [1973] S.C.R. 38. Moreover, the right of a municipality to rely upon the provisions of its bylaws<br />

<strong>ca</strong>nnot be waived, lost or vitiated by acquiescence, laches, or estoppel (Langley (Township) v. Wood, 1999<br />

BCCA 260).<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK<br />

1995 Zoning Bylaw<br />

[26] The authority for a lo<strong>ca</strong>l government to pass bylaws to regulate the use of land is s. 903 of the LGA.<br />

[27] Part V, s. 4 of the 1995 Zoning Bylaw provides for a general prohibition against any use not expressly<br />

permitted in each zone. It proscribes as follows:<br />

In each zone created under Part V, Section 1 of this Bylaw:<br />

(A)<br />

(B)<br />

the only uses permitted are those listed in respect of each zone under the heading “Permitted<br />

Uses” in Section 1 to 21 of Part X of this Bylaw; and<br />

uses not listed in respect of a particular zone are prohibited.<br />

[28] Lands in the RS1 Zone are permitted to be used only for the following purposes:<br />

a) single family dwelling,<br />

b) parks and playgrounds,<br />

c) home occupations,<br />

d) buildings and structures auxiliary to all of the above uses.<br />

[29] A “single family dwelling” is defined as:<br />

a building, excluding single wide and double wide mobile homes, that: consists of one dwelling unit;<br />

is lo<strong>ca</strong>ted on an approved continuous perimeter foundation; and is occupied or intended to be<br />

occupied by one family.<br />

[30] A “dwelling unit” is defined as:<br />

one or more habitable rooms constituting one self-contained unit with a separate entrance, and used<br />

or intended to be used for living and sleeping purposes for not more than one family and containing<br />

only: one kitchen equipped with a sink and one set of cooking facilities; one or more bathrooms with<br />

a water closet, wash basin and bath or shower, and; not more than one electri<strong>ca</strong>l service;<br />

[31] “Family” is defined as:<br />

1. an individual or two (2) or more persons related by blood, marriage, adoption or foster<br />

parenthood sharing one dwelling unit; or<br />

2. not more than five (5) unrelated persons living together as a non-profit group in a dwelling unit<br />

and using a common cooking area.<br />

[32] A “home occupation” is defined as:<br />

an occupation or profession which is ancillary and subordinate to the use of a dwelling unit for<br />

residential purposes or the residential use of a parcel occupied by a dwelling unit; (emphasis added)<br />

[33] Part IV, s. 13 provides further restrictions and requirements for home occupations. For instance, no<br />

more than 50 square meters of a dwelling may be used in conjunction with a home occupation and only the<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

inhabitants of the principal dwelling may own the home occupation on the site occupied by the principal<br />

dwelling unit.<br />

[34] A “bed and breakfast”, which is defined as “an occupation conducted within a principal dwelling unit by<br />

the residents of the dwelling unit”, is a permitted form of home occupation.<br />

[35] A Tourist Commercial/Heritage Zone (CT4) has “hotels” as one of its permitted uses.<br />

2006/2008 Zoning Bylaws<br />

[36] Section 6.4 of the 2006/2008 Zoning Bylaws again provides a general prohibition against all uses not<br />

listed in any respective zone:<br />

In each zone created under Section 6.1 of this Bylaw:<br />

1. The only uses permitted are those listed in respect of each zone under the heading “Permitted<br />

Uses” in Section 10.0 to 15.0 of this Bylaw; and<br />

2. uses not listed in respect of a particular zone are prohibited<br />

[37] The permitted uses of lands in the RS1 Zone contained in s. 11.1.1 of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw are<br />

identi<strong>ca</strong>l to those contained in s. 11.1.1 of the 2006 Zoning Bylaw. The restrictions on home occupations (s.<br />

7.17) and private visitor accommodations (s. 7.19) in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw are nearly identi<strong>ca</strong>l to those in<br />

the 2006 Zoning Bylaw. Similarly, the definitions of principal and secondary use (s. 4) are virtually identi<strong>ca</strong>l in<br />

both the 2008 Zoning Bylaw and the 2006 Zoning Bylaw.<br />

[38] With respect to lands in the RS1 Zone, the 2006 and 2008 Zoning Bylaws list “single detached<br />

dwelling” as the only permitted principal use. A single detached dwelling is defined as meaning “a detached<br />

building consisting of one dwelling unit that does not exceed a width-to-length ratio of 1:4, and has a<br />

minimum width of 5.0 metres”.<br />

[39] A “dwelling unit” is defined as meaning “one or more habitable rooms constituting one self-contained<br />

unit which has a separate entrance, and which contains washroom facilities, and which is designed to be<br />

used for living and sleeping purposes”.<br />

[40] The 2006/2008 Zoning Bylaws list the permitted secondary uses, including:<br />

(c)<br />

...<br />

(f)<br />

home occupations, subject to Section 7.17 (Section 7.11 in the 2006 Zoning Bylaw);<br />

private visitor accommodation, subject to Section 7.19 (Section 7.13 in the 2006 Zoning<br />

Bylaw).<br />

[41] A “principal use” is defined as meaning “the main purpose for which the parcel, building or structure is<br />

used”. Secondary Use is defined as meaning “a use that is permitted only in conjunction with a designated<br />

principal use for each zone”.<br />

[42] With respect to home occupations, s. 7.17(2) of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw (s. 7.11(2) of the 2006 Zoning<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

Bylaw) states that “no more than 50% of the floor area to a maximum of 75 m 2 of a principal dwelling unit<br />

must be used in connection with the home occupation”.<br />

[43] The term “private visitor accommodation” is a separate <strong>ca</strong>tegory from a home occupation and is not<br />

subject to the same restrictions. Section 4 of the 2006/2008 Zoning Bylaws provides the following definition<br />

for “private visitor accommodation”:<br />

an occupation conducted within a principal dwelling unit, by the residents of the dwelling unit, which<br />

provides sleeping accommodations to the traveling public (Provincially exempt). A bed and breakfast<br />

operation is a form of private visitor accommodation and includes the provision of a morning meal for<br />

the persons using the sleeping accommodations.<br />

[44] A “principal dwelling unit” is defined as a “principal residential unit” that: “(b) is used or intended for<br />

use as a residential premises, ...”.<br />

[45] The term “residential” is not defined anywhere in the 2006/2008 Bylaws; however, “residence” is<br />

defined as a “permanent or seasonal home on a lot”.<br />

[46] There is no indi<strong>ca</strong>tion in the 2006/2008 Bylaws as to what is meant by “Provincially exempt”.<br />

[47] Section 7.19 of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw (s. 7.13 of the 2006 Zoning Bylaw) states that:<br />

a private visitor accommodation, which includes a bed and breakfast operation, is permitted where<br />

listed as a permitted use, provided that:<br />

1. it is lo<strong>ca</strong>ted within one principal dwelling unit on the parcel, and not permitted in conjunction<br />

with a secondary suite;<br />

2. no more than eight (8) patrons shall be accommodated within the dwelling unit;<br />

3. not more than three (3) bedrooms shall be used for parcels less than 0.8 ha, and not more than<br />

four bedrooms for parcels greater than 0.8 ha;<br />

4. no cooking facilities shall be provided for within the bedrooms intended for the private visitor<br />

accommodation operation;<br />

5. no patron shall stay within the same dwelling for more than thirty (30) days in a <strong>ca</strong>lendar year;<br />

and<br />

6. only the residents of the principal dwelling unit may <strong>ca</strong>rry on the private visitor accommodation<br />

on the site occupied by the principal dwelling unit.<br />

[48] Section 6.4.3 was introduced in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw and proscribes that “the headings in respect of<br />

each zone are part of this Bylaw”.<br />

[49] The heading in s. 7.19 of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw for “private visitor accommodation” is entitled “Private<br />

Visitor Accommodation (Bed and Breakfast)”. “Bed and breakfast” is defined as “a form of ‘private visitor<br />

accommodation’ conducted within a principal dwelling unit which provides sleeping accommodations to<br />

visitors and includes the provision of a morning meal for those persons using the sleeping accommodations”.<br />

ANALYSIS<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

General Legal Framework<br />

[50] Bylaw interpretation is grounded in the well-settled principles of the modern approach to statutory<br />

interpretation. Recently, in North Pender Island Lo<strong>ca</strong>l Trust Committee v. Conconi, 2010 BCCA 494, at para.<br />

13, the Court of Appeal, quoting Elmer Driedger, The Construction of Statutes (Toronto: Butterworths, 1974)<br />

at 67, affirmed that:<br />

... the words of an [enactment] are to be read in their entire context, in their grammati<strong>ca</strong>l and ordinary<br />

sense harmoniously with the scheme of the [enactment], the object of the [enactment], and the<br />

intention of [the legislative body that passed the enactment].<br />

[51] With respect to interpreting zoning bylaws, the Court in North Pender Island Lo<strong>ca</strong>l Trust Committee<br />

articulated the governing principles which inform the analysis:<br />

14 In interpreting zoning or land use bylaws, one must have regard to their general purpose.<br />

That purpose was described in I.M. Rogers, Canadian Law of Planning and Zoning (Toronto:<br />

Carswell, 1973), which was cited with approval in Whistler (Resort Municipality) v. Miller, 2001 BCSC<br />

100, 20 M.P.L.R. (3d) 128 at para. 51, aff’d 2002 BCCA 347, 32 M.P.L.R. (3d) 29, as follows:<br />

The principal purpose of zoning regulations, as with restrictive covenants, is to preserve<br />

property values by prohibiting uses which are believed to be deleterious to neighbourhoods<br />

mainly residential in character ...<br />

[52] In Neilson v. Langley Township (1982), 134 D.L.R. (3d) 550, Hinkson J.A. summarized the general<br />

interpretive principle at para. 18:<br />

In the present <strong>ca</strong>se, in my opinion, it is necessary to interpret the provisions of the zoning by-law not<br />

on a restrictive nor on a liberal approach but rather with a view to giving effect to the intention of the<br />

municipal council as expressed in the by-law upon a reasonable basis that will accomplish that<br />

purpose.<br />

[53] Each bylaw must be interpreted within its own particular context and in light of its own wording. As a<br />

result, definitions in other <strong>ca</strong>ses are of little assistance: Conconi, at para. 25.<br />

[54] A statute is presumed not to have superfluous words or provisions and the courts should presume that<br />

all words were included for a specific purpose and should be given effect .The rule of effectivity was<br />

described by Ruth Sullivan in Driedger on the Construction of Statutes, 5 th ed. (Markham, ON: LexisNexis,<br />

2008) at 210: “every word in a statute is presumed to make sense and to have a specific role to play in<br />

advancing the legislative purpose”.<br />

[55] As a result of the presumption of implied exclusion, in <strong>ca</strong>ses where a permitted use is expressly listed<br />

in one zone, but not another, the courts have found that the municipality intended to exclude that specific use<br />

from the more general provision: <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> of Kootenay Boundary v. McKay, 2008 BCSC 174.<br />

[56] For instance, in S.R.V. Developments Ltd. v. Courtenay (City) (1992), 12 M.P.L.R. (2d) 154 (B.C.S.C.),<br />

aff'd 42 M.P.L.R. (2d) 261 (C.A.), the Court considered whether the general classifi<strong>ca</strong>tion of "retail and<br />

wholesale outlets”, which was permitted in a C-2 zone, also included liquor stores. The bylaw expressly used<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

“liquor store” in the C-1 zone. The Court held that it was open to the municipality to limit the ordinary<br />

definition of words, in this <strong>ca</strong>se “retail and wholesale outlets”. By appli<strong>ca</strong>tion of the principle of implied<br />

exclusion, the Court concluded that by using "liquor store" in C-1, the municipality had removed the term<br />

"liquor store" from the more generic classifi<strong>ca</strong>tion of "retail and wholesale outlets” such that the liquor store<br />

was not a permitted use in the C-2 zone.<br />

[57] In Thomas C. Watkins Ltd. v. Cambridge Leaseholds Ltd., [1966] S.C.R. v. (unreported), the zoning<br />

bylaw established five different commercial zones. All five zones listed "retail stores" as a permitted use but<br />

only one listed "department store" as a permitted use. The issue was whether the expression "retail store"<br />

included a department store. McGillivray J.A., dissenting at the Ontario Court of Appeal, held that by making<br />

the two items separate and distinct in the bylaw, the municipality intended to draw a distinction between the<br />

two terms, even though, as a generic term, "retail store" would normally include a department store. On<br />

appeal, the Supreme Court of Canada expressly adopted the dissenting reasons of McGillivray, J.A. The<br />

relevant portions of the judgment of McGillivray, J.A. were subsequently cited with approval by the Supreme<br />

Court of Canada in Bayshore Shopping Centre v. Nepean (Township), [1972] S.C.R. 755.<br />

Issue 1: Has there been a breach of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw<br />

[58] The first question that arises with respect to compliance with the 2008 Zoning Bylaw is whether the<br />

defendant’s present use of the Property qualifies as a permissible principal use; namely, as a single detached<br />

dwelling in the RS1 Zone.<br />

[59] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> asserts that the defendants’ use of the Property is not a permitted principal use in<br />

the RS1 Zone. The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> relies on the prohibitive clause in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw which prohibits<br />

any use in a given zone other than those uses which are expressly permitted.<br />

[60] The defendants submit that their principal use of the Property is as a single detached dwelling. In<br />

support of this position, they emphasize that their use of the Property is not limited to the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals.<br />

They refer to their various non-renting uses - such as using the Property themselves, letting friends and<br />

family use it, or simply leaving the Property va<strong>ca</strong>nt - and maintain that the permissible primary use as a<br />

single detached dwelling is satisfied by all of them, regardless of whether the defendants are physi<strong>ca</strong>lly<br />

present at the Property.<br />

[61] The defendants assert that as a corollary to the principle of implied exclusion, the Court, in finding that<br />

a particular use is prohibited in a zone, must find that the particular use falls clearly within some other class<br />

of use in another zone. The defendants contend that there is no other <strong>ca</strong>tegory of use that expressly<br />

<strong>ca</strong>ptures their present use of the Property as a short-term va<strong>ca</strong>tion rental. In particular, the defendants say<br />

that their use is not more appropriately classified as a motel, hotel, or resort, which are expressly permitted in<br />

other zones. Therefore, they say their use as a short-term va<strong>ca</strong>tion rental should presumptively be permitted<br />

in the zone for residential single detached dwellings.<br />

[62] It emerges from the authorities that the provisions in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw must be interpreted<br />

purposively and within the context of the bylaw as a whole.<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

[63] I am not persuaded that the general prohibitive clause is only engaged if the challenged use more<br />

appropriately fits in another class of uses in another zone. Rather the appropriate inquiry is to examine what<br />

is permitted in a given zone; any other uses are prohibited.<br />

[64] A “single detached dwelling” is defined as “a detached building consisting of one dwelling unit that<br />

does not exceed a width-to-length ratio of 1:4, and has a minimum width of 5.0 metres”. This definition refers<br />

solely to the structure, not to any activities in the dwelling. However, a “dwelling unit” is defined as meaning<br />

“one or more habitable rooms constituting one self-contained unit which has a separate entrance, and which<br />

contains washroom facilities, and which is designed to be used for living and sleeping purposes” (emphasis<br />

added). The only restriction with respect to the activities that are permissible in the use of a dwelling unit is<br />

that it must be designed to be used for living and sleeping purposes. There is no express provision which<br />

states that the dwelling unit must be put to a “residential” use.<br />

[65] However, the heading, which is a part of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw by virtue of s. 6.4.3, describes the<br />

RS1 Zone as a “Residential Single Family One Zone”. The Court must interpret the provisions so as to give<br />

effect to the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s intention as reasonably expressed in the bylaw. In my view the intention of<br />

the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> as expressed through the heading is that the single family dwelling must be put to a<br />

“residential use”. Notably, the term “residential” is not defined anywhere in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw.<br />

[66] The plain meaning of “residential” is connected with or pertaining to a residence. “Residence” is<br />

defined in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw as referring to a “permanent or seasonal home on a lot”.<br />

[67] The meaning of the terms “residential” and “reside” were considered by the BCCA in Kamloops (City)<br />

v. Northland Properties Ltd., 2000 BCCA 344 where the Court of Appeal stated as follows at para. 14:<br />

... they refer to having one’s home in a particular place “for a considerable length of time”, and define<br />

“residential” to mean “occupied mainly by private houses”...<br />

[68] Black’s Law Dictionary, 8th ed. (St. Paul: West Pub. Co., 2004) at 1335 defines residence as:<br />

The act or fact of living in a given place for some time. 2. The place where one actually lives, as<br />

distinguished from a domicile. Residence usually just means bodily presence as an inhabitant in a<br />

given place; domicile usually requires bodily presence plus an intention to make the place one's<br />

home. A person thus may have more than one residence at a time but only one domicile.<br />

Sometimes, though, the two terms are used synonymously. ...<br />

[69] In Whistler (Resort Municipality) v. Miller, 2001 BCSC 100, the primary authority relied upon by the<br />

<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>, the term "residential" was expressly defined in the bylaw as meaning a fixed place of living,<br />

excluding any temporary accommodation, to which a person intends to return when absent. The term "tourist<br />

accommodation" was also defined as meaning a building containing one or more habitable rooms or dwelling<br />

units that are used primarily for temporary lodging by visitors. The Court held at para. 23 that it was<br />

therefore:<br />

...untenable to suggest that the rental of a detached dwelling to short term paying guests is a normal<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

and customary residential use. ...this is particularly true in the context of the Bylaw where<br />

Residential/Tourist Accommodation Zones have been established and in which detached dwelling<br />

and tourist accommodation uses are expressly permitted.<br />

[70] In the 2008 Zoning Bylaw, unlike the bylaw considered by the Court in Whistler, there is no express<br />

provision to oust temporary accommodation as a permissible use in the RS1 Zone. This renders the analysis<br />

in Whistler distinguishable.<br />

[71] I do accept, nonetheless, that on the principles articulated by the Court in Whistler, the rental of a<br />

detached dwelling to short-term paying guests is not a normal and customary residential use in the sense of<br />

being the principal use for this type of property.<br />

[72] Signifi<strong>ca</strong>ntly, the 2008 Zoning Bylaw defines a “secondary use” as “a use that is permitted only in<br />

conjunction with a designated principal use for each zone”. The 2008 Zoning Bylaw includes a list of<br />

permissible secondary uses for each zone. “Private visitor accommodation” is expressly permitted as a<br />

secondary use in the RS1 Zone. It follows, that the explicit listing of private visitor accommodation as a<br />

secondary use demonstrates that the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> did not intend for short-term va<strong>ca</strong>tion rentals to fall<br />

within the scope of the approved principal use as a single detached dwelling. Applying the principles of<br />

effectivity and implied exclusion, I conclude that short-term va<strong>ca</strong>tion rentals are not permissible as a principal<br />

use in the RS1 Zone. On a proper interpretation of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw, short-term va<strong>ca</strong>tion rentals are<br />

only permissible as a secondary use in the RS1 Zone if these rentals qualify as “private visitor<br />

accomodation.”<br />

Whether the defendants have been lawfully using the Property as a “private visitor<br />

accommodation”<br />

[73] Having determined that short-term va<strong>ca</strong>tion rentals are only permissible as a secondary use in the<br />

RS1 Zone, the question in this <strong>ca</strong>se is whether the defendants’ use of the property qualifies as “private visitor<br />

accommodation” and if so, whether the defendants’ use is secondary to the principal residential use of the<br />

Property as a single detached dwelling.<br />

[74] A “private visitor accommodation” is defined as “an occupation conducted within a principal dwelling<br />

unit, by the residents of the dwelling unit, which provides sleeping accommodation to the traveling public<br />

(Provincially exempt)”. A bed and breakfast operation is stated to be “a form of private visitor<br />

accommodation”.<br />

[75] It emerges from the submissions that there are three principal objections to the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals<br />

qualifying as private visitor accommodation under the 2008 Zoning Bylaw:<br />

(1) by definition – the occupation must be conducted within a principal dwelling unit, by the residents<br />

of the dwelling unit,<br />

(2) pursuant to s. 11.1.1 private visitor accommodation is permitted only as a secondary use in the<br />

RS1 Zone,<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

(3) pursuant to s. 7.19.6 only the residents of the principal dwelling unit may <strong>ca</strong>rry on the private<br />

visitor accommodation on the site occupied by the principal dwelling unit. I note parentheti<strong>ca</strong>lly<br />

that there was no suggestion that the defendants contravened the provisions of ss. 7.19.1-<br />

7.19.5.<br />

[76] I will address each of these issues in turn.<br />

(i) Are the defendants the “residents” of the Property<br />

[77] As a threshold issue the defendants must properly be characterized as “the residents” of the Property.<br />

The 2008 Zoning Bylaw does not define the term “resident”.<br />

[78] The authorities mandate that where some, but not all, terms have been defined in a bylaw, the courts<br />

must not apply a restrictive meaning to an undefined term; that term should be ascribed its ordinary meaning.<br />

[79] The Court of Appeal in Neilson applied this principle in determining what meaning should be given to<br />

the term “golf-course” in a bylaw. The Court noted that other terms in the bylaw had been defined in the<br />

schedule, and the effect of defining these terms restricted the meaning that might otherwise be attributed to<br />

such terms. However, no such restrictions had been imposed with respect to the term “golf-course”. The<br />

Court concluded therefore that “golf-course” was intended to have a broad meaning and that anything that<br />

<strong>ca</strong>n be regarded as reasonably coming within the operation of a golf-course was a permitted use: see also<br />

Castle Trucking Ltd. v. Central Saanich (<strong>District</strong>), [1994] B.C.J. No. 2045 (Q.L.)(S.C.).<br />

[80] The law has recognized that a person may have more than one residence: see e.g. Fox v Stirk,<br />

Ricketts v Registration Officer for the City of Cambridge, [1970] 3 All E.R. 7 at 11-12. Signifi<strong>ca</strong>ntly, the 2008<br />

Zoning Bylaw indi<strong>ca</strong>tes that a “residence” <strong>ca</strong>n be either a permanent or a seasonal home, which implies that<br />

“residency” and “residents” <strong>ca</strong>n be either permanent or seasonal as well.<br />

[81] In my view, in applying the ordinary meaning of the term “residents”, the defendants are properly<br />

characterized as residents of the Property. Although they do not reside at the Property full-time, they have<br />

resided there for some time each year since 2004. They spend between one to three months a year at the<br />

Property. The defendants return to the Property habitually. They have undertaken renovations of the<br />

Property. The criti<strong>ca</strong>l and uncontroverted evidence of the defendants is that the Property is their second<br />

home; there was no evidence adduced to refute this characterization.<br />

[82] In summary on this issue, I am satisfied that for the purpose of <strong>ca</strong>rrying on the visitor accommodation,<br />

the defendants are the residents of the Property.<br />

(ii) Was “private visitor accommodation” the secondary use<br />

[83] The next issue for determination is whether the defendants’ “private visitor accommodation” is properly<br />

characterized as a secondary use of the Property.<br />

[84] The uncontroverted evidence is that the Property was only rented out for approximately five weeks per<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

year. The defendants live there themselves for approximately one to three months per year. The Property is<br />

va<strong>ca</strong>nt much of the time, and is used by the defendants’ friends and family about two weeks per year.<br />

[85] I am satisfied that the overall use of the Property as a private visitor accommodation is not the<br />

principal use.Rather it is a secondary use in conjunction with the defendants’ overall residential use of the<br />

Property.<br />

(iii) Does s. 7.19.6 require the residents to be on site<br />

[86] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> forcefully asserts that the 2008 Zoning Bylaw requires the residents of a property<br />

to be on site during the provision of private visitor accommodation to ensure that the use of the property is<br />

consistent with a residential neighbourhood.<br />

[87] The essential question thus is whether or not in order for the use to qualify as private visitor<br />

accommodation, s. 7.19.6 requires that a resident be on site when they rent out their property. For the<br />

reasons set out below, I am not persuaded that the section <strong>ca</strong>n reasonably be interpreted to include such a<br />

requirement.<br />

[88] I first address the contention by the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> that private visitor accommodation is intended to<br />

refer exclusively to a bed and breakfast operation and therefore the residents are required to be on site<br />

during any short-term rentals.<br />

[89] With respect to the submission that the term “private visitor accommodation” is intended to refer<br />

exclusively to a bed and breakfast, I am not persuaded that this is a tenable proposition based on a plain<br />

reading of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw. The definition of “private visitor accommodation” describes a bed and<br />

breakfast operation as a form of private visitor accommodation. Likewise, s. 7.19 describes private visitor<br />

accommodation as including a bed and breakfast operation. The 2008 Zoning Bylaw clearly contemplates<br />

forms of private visitor accommodation beyond a bed and breakfast operation. I therefore reject the position<br />

taken by the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> that private visitor accommodation is intended to refer to bed and breakfasts<br />

exclusively.<br />

[90] There is no provision in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw which expressly stipulates that the residents of a<br />

property must be on site during the use of the property as a private visitor accommodation. On a plain<br />

reading of the definition of a private visitor accommodation, it is clear that only the residents of a principal<br />

dwelling unit may conduct the business of the private visitor accommodation. Similarly, s. 7.19.6 states that<br />

only the residents of the principal dwelling unit may <strong>ca</strong>rry on the private visitor accommodation on the site<br />

occupied by the principal dwelling unit. Does this require the residents to be “on site” Or does it simply<br />

mean that if someone is to be <strong>ca</strong>rrying on the private visitor accommodation on site, it <strong>ca</strong>n only be the<br />

residents that do so In my view, the words of the provision reasonably support the latter interpretation.<br />

[91] Section 7.19.6 plainly sets out a restriction on who may <strong>ca</strong>rry on a visitor accommodation on site, not<br />

on where the resident must be during the use of the property as a private visitor accommodation. There is no<br />

principled basis, either through statutory interpretation or by appli<strong>ca</strong>tion of the relevant jurisprudence, to<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

interpret the provision as importing a requirement that the resident be on site during the private visitor<br />

accommodation.<br />

[92] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> points out that the Court may consider evidence of administrative interpretation<br />

in order to resolve any ambiguities in a bylaw: Conconi, at para. 29. Contrary to their submission, however, I<br />

am not persuaded that the 2008 Zoning Bylaw is ambiguous insofar as it refers to “residents” in the definition<br />

of “private visitor accommodation” or in s. 7.19.6.<br />

[93] For completeness I have nonetheless considered Ms. Aylwin’s evidence, to which she deposed in May<br />

2011, after she was promoted to the role of Bylaw Enforcement Coordinator, that the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s<br />

administrative and enforcement staff have consistently interpreted s. 7.19.6 of the 2008 Zoning Bylaw as<br />

requiring the residents of a principal dwelling unit to be present on site if they wish to use their property for<br />

the purpose of providing private visitor accommodation in the RS1 Zone. However, In her affidavit on the<br />

point she purports to use the term “resident” interchangeably with the terms “occupier” and “inhabitant”, which<br />

terms are not referenced in the provisions regarding “private visitor accommodation”.<br />

[94] The authorities direct that the courts are to interpret bylaws so as to give effect to the intention of the<br />

municipal authority as expressed in the bylaw on a reasonable basis: Neilson, at para. 18. I am not<br />

persuaded that, on an objective analysis, the interpretation advo<strong>ca</strong>ted by the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> is expressed<br />

in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw.<br />

[95] The parties made submissions on the appli<strong>ca</strong>bility of the presumption of validity and whether the<br />

disputed provisions are intra vires the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> under the LGA. In view of my findings it is<br />

unnecessary to address those submissions.<br />

[96] In the result, I conclude that the defendants, in compliance with the 2008 Zoning Bylaw, have been<br />

lawfully operating their private visitor accommodation as a secondary use of their single family dwelling.<br />

[97] This is sufficient to dispose of this appli<strong>ca</strong>tion. However, for completeness, I turn to consider the<br />

appli<strong>ca</strong>tion of the doctrine of lawful non-conforming use.<br />

Issue 2: Can the defendants rely on lawful non-conforming use<br />

[98] The defendants rely on the protection of s. 911(1) of the LGA and submit that they meet the criteria for<br />

lawful non-conforming use.<br />

Legal Framework<br />

[99] Lawful non-conforming use is permitted under certain circumstances, as set out in s. 911 of the LGA.<br />

This section provides that a use of land that is lawful when a bylaw is adopted, but is subsequently rendered<br />

unlawful by the enactment of the bylaw, may continue. Section 911 of the LGA provides as follows:<br />

If, at the time a bylaw under this Division is adopted,<br />

(a) land, or a building or other structure is lawfully used, and<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

(b) the use does not conform to the bylaw,<br />

the use may be continued as a non-conforming use, but if the non-conforming use is discontinued for<br />

a continuous period of 6 months, any subsequent use of the land, building or other structure<br />

becomes subject to the bylaw.<br />

[100] Notably, if a use has been discontinued for a continuous period of six months, the user <strong>ca</strong>n no longer<br />

rely on the exemption provided for lawful non-conforming use.<br />

[101] Subsection 911(2) provides that a use of land on a seasonal basis is not discontinued as a result of<br />

normal seasonal practices, including<br />

(a) seasonal, market or production cycles,<br />

...<br />

(c) the repair, replacement or installation of equipment to meet standards for the health or safety<br />

of people or animals.<br />

[102] Section 911(5) explicitly limits the scope of renovation activities permitted on properties relying on the<br />

lawful non-conforming use exemption:<br />

(5) A structural alteration or addition, except one that is required by an enactment or permitted<br />

by a board of variance under section 901 (2), must not be made in or to a building or other structure<br />

while the non-conforming use is continued in all or any part of it.<br />

[103] The onus is on the party alleging lawful non-conforming use to prove it on a balance of probabilities:<br />

Country Lane Developments v. Coquitlam (City), 2003 BCSC 1121; North Vancouver (City) v. Vanneck<br />

(1997), 39 M.P.L.R. (2d) 249 (B.C.S.C.).<br />

(i) Was the use permitted under the 1995 Zoning Bylaw<br />

[104] The pivotal question is whether the use of the Property as a short-term va<strong>ca</strong>tion rental was permitted<br />

under the 1995 Zoning Bylaw.<br />

[105] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> argues that the defendants <strong>ca</strong>nnot rely on the protection of the law of nonconforming<br />

use be<strong>ca</strong>use the use of the Property as a commercial tourist accommodation was never a<br />

permitted use under the 1995 Zoning Bylaw. Under the 1995 Zoning Bylaw, the only relevant permitted uses<br />

for the defendants’ Property in the RS1 Zone were as a “single family dwelling” or a “home occupation”. The<br />

defendant’s use clearly would not qualify as a “home occupation”, as this use is only permissible if involves<br />

less than 50 square metres of the floor area of the dwelling unit and the defendants admit that the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion<br />

Rentals provided use of the Property as a whole. The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> submits that the Property was not<br />

being used as a “single family dwelling” either, as this refers to a dwelling unit occupied or intended to be<br />

occupied by one family. The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> points out that the defendants admit they rented the Property<br />

out on a short-term basis to various va<strong>ca</strong>tioning families throughout the years. Hence, they submit, the<br />

defendants were in breach of the 1995 Zoning Bylaw and <strong>ca</strong>nnot rely on the law of non-conforming use<br />

be<strong>ca</strong>use their use was never “lawful”.<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

[106] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> also contends that under the 1995 Zoning Bylaw the defendants’ use of the<br />

Property to provide temporary rental accommodation would have been allowed in other zones within the<br />

Naramata area, namely the general tourist commercial zone and the tourist commercial heritage zone, both<br />

of which permit motels, hotels, and resorts. I note parentheti<strong>ca</strong>lly that, as in the 2008 Zoning Bylaw, there is<br />

no reference whatsoever in the 1995 Zoning Bylaw to a “commercial tourist accommodation”.<br />

[107] The defendants submit that their use of the Property met the criteria for use as a “single family<br />

dwelling” under the 1995 Zoning Bylaw: the building contains one “dwelling unit” and is occupied or intended<br />

to be occupied by one “family” at a time.<br />

[108] As mentioned earlier, the defendants’ uncontroverted evidence is that the use of the Property since<br />

2005 <strong>ca</strong>n be characterized as follows: va<strong>ca</strong>nt much of the time, used by the defendants as a second home,<br />

used by friends and family members of the defendants from time to time, and available for rent to one family<br />

at a time by the week, mainly in the summer months.<br />

[109] The Property does not meet the definition of a “motel” as it was not designed to provide temporary<br />

accommodation to the travelling public. Nor is the Property a resort “intended to be used by the public on a<br />

temporary or seasonal basis for recreational purposes”. The term “hotel” is not defined; however, the<br />

Concise Oxford English Dictionary, 9 th ed. defines it as “an establishment providing accommodation and<br />

meals for travellers and tourists”. Overall, I am satisfied that the rental by the defendants of their single family<br />

residence clearly does not amount to the operation of a hotel, motel, or resort. I therefore conclude that the<br />

short-term rental of a single family dwelling does not expressly fall within a prescribed use in another zone of<br />

the 1995 Zoning Bylaw.<br />

[110] Since the defendants’ use did not qualify as a home occupation or a bed and breakfast, the only<br />

pertinent use is as a single family dwelling. Notably the 1995 Zoning Bylaw does not distinguish between<br />

principal and secondary uses - unlike the 2008 Zoning Bylaw there is no prescribed secondary use as a<br />

temporary visitor accommodation. Nor is the heading of Residential Single Family One Zone (RS1) expressly<br />

stated as a part of the bylaw.<br />

[111] Unlike the bylaws considered by the Court in Whistler, the 1995 Zoning Bylaw does not provide a clear<br />

and explicit statement of intent to exclude temporary accommodation; there are no clear restrictions or<br />

definitions which limit the use to which a single family dwelling <strong>ca</strong>n be put.<br />

[112] The 1995 Zoning Bylaw states that a “single family dwelling” means a building that consists of one<br />

dwelling unit; is lo<strong>ca</strong>ted on an approved continuous perimeter foundation; and is occupied or intended to be<br />

occupied by one family. The definition of a “dwelling unit” primarily refers to the physi<strong>ca</strong>l characteristics of the<br />

dwelling and requires that it be used or intended to be used for the living and sleeping of not more than one<br />

family. There is, however, no express stipulation that s single family dwelling could not be used by different<br />

families at different times in the year. Rather one would assume that “occupied by one family” means that<br />

only one family could occupy the residence at a time; not that another family could never stay there. If such<br />

were the <strong>ca</strong>se, a resident could never allow another family to use their property, which would be a signifi<strong>ca</strong>nt<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

restriction on the rights of the resident. If the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> had intended to impose such a restriction, it<br />

should have done so expressly.<br />

[113] There is no express provision in the 1995 Zoning Bylaw to indi<strong>ca</strong>te that providing short-term rentals to<br />

one family at a time in a person’s private residence would not be permitted in a single family dwelling or that it<br />

would be permitted in another zone so as to be impliedly excluded from the general use as a single family<br />

dwelling.<br />

[114] In the result, I conclude that the defendants’ operation of the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals was compliant with the<br />

1995 Zoning Bylaw at the time the defendants commenced this use in 2005.<br />

(ii) Was this use continued<br />

[115] The next question with respect to lawful non-conforming use is whether the present use is, in<br />

substance, the same as it was in 2005. Moreover, that use must not have been discontinued for a period of<br />

more than six consecutive months.<br />

Legal Framework<br />

[116] In Sanders v. Langley (Township), 2010 BCSC 1543, at para. 33, Wedge J. distilled the principles for<br />

determining the relevant "use" under s. 911(1) of the LGA:<br />

... where a property owner <strong>ca</strong>n demonstrate that at the time of a new zoning bylaw his or her<br />

property was actually used in a manner that was a lawfully permitted use but for the new bylaw, the<br />

property owner is entitled to continue that formerly lawful, but now non-conforming use. The property<br />

owner must establish the actual use of the property on the exact date of the adoption of the new<br />

bylaw (City of North Vancouver v. Vanneck (1997), 39 M.P.L.R. (2d) 249 (B.C.S.C.) and <strong>ca</strong>ses cited<br />

therein).<br />

[117] In Sunshine Coast (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Bailey, (1995), 15 B.C.L.R. (3d) 16 (S.C.) at para. 31, the<br />

Court described the purpose of the law of non-conforming use and observed that the courts have adopted a<br />

liberal approach to interpreting the statutory lawful non-conforming use exemption in favour of the user:<br />

Presumably, it is the concept of fairness that supplies the underlying rationale for the statutory nonconforming<br />

use exemption, for its liberal interpretation by the courts through development of the<br />

"commitment to use" doctrine, and for the accompanying proposition that any doubt as to prior use<br />

ought to be resolved in favour of the owner. To prohibit completion of a land development project to<br />

which there has been an unequivo<strong>ca</strong>l commitment, including signifi<strong>ca</strong>nt physi<strong>ca</strong>l alteration to the site,<br />

savours of unfairness be<strong>ca</strong>use it is tantamount to giving the zoning bylaw retroactive effect, to the<br />

prejudice of the owner.<br />

[118] The liberal interpretation in favour of users, noted in Sunshine Coast, also applies with respect to<br />

whether a use has been discontinued. The courts have taken a broad approach to “use” in order to avoid the<br />

expiration of a lawful non-conforming use through discontinuance.<br />

[119] For instance, in Cowichan Valley (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Ward (1994), 95 B.C.L.R. (2d) 58 (C.A.), the<br />

Court considered whether the operation of a sawmill was a lawful non-conforming use pursuant to s. 722 of<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

the Municipal Act, R.S.B.C. 1979, c. 290, which provided that a use would be protected as a lawful nonconforming<br />

use unless it was discontinued for a period of 30 days. There were periods of 30 days and more<br />

during which the mill itself did not operate. One winter, the roof collapsed and as a result the mill was<br />

inoperable for some time. However the Court held that this did not mean that the non-conforming use of the<br />

premises was discontinued, ‘just as it could not be said that a snow covered golf course was not used as a<br />

golf course’. The Court of Appeal concluded that although the sawmill property was not always running, it<br />

was still protected as a non-conforming use. The Court reasoned as follows at para. 13:<br />

it is non-use of the premises as distinct from non-operation of the mill that must be shown. All that<br />

the trial judge found was that the mill did not operate for periods in excess of 30 days. That is not<br />

enough. There must be a discontinuance of the use of the premises in order to satisfy s. 722(2). That<br />

is not shown by the evidence. (emphasis added)<br />

[120] In Osoyoos (Town) v. Nobbs, 2002 BCSC 1743, aff’d 2004 BCCA 431, Mr. Justice Meztger<br />

considered whether the use of the owner’s travel trailer for residential purposes and the use of the lot as a<br />

recreational vehicle park qualified as lawful non-conforming use. The previous owners and present owners<br />

had used the site every summer for <strong>ca</strong>mping. However, one of the issues raised was the fact that the owners<br />

only used the land for “summer <strong>ca</strong>mping”. Hence, the Town argued that the prior use was discontinued<br />

under s. 911 of the LGA, as there were periods of longer than six months that had elapsed between each<br />

<strong>ca</strong>mping use. Nevertheless, the Court found that there had been on-going use protected by s.911. The Court<br />

concluded as follows:<br />

13. The purpose of allowing a non-conforming use to continue after a bylaw has been passed is<br />

to protect the status quo. This lot is to be used for summer <strong>ca</strong>mping, and that use has never<br />

changed. I find that the lapse provisions only apply if this lot was not used for <strong>ca</strong>mping in the May<br />

through September period in any one year. There has never been a thirty day or six month lapse of<br />

that particular use. The status quo is preserved ...<br />

(emphasis mine)<br />

[121] On appeal, Saunders J.A. writing for the Court, upheld the trial judgment. She noted as follows with<br />

respect to the proper approach to determining the relevant “use” in the context of an alleged discontinuance:<br />

20. In my view the issue here on "use" is not whether the use of this lot meets a particular<br />

definition in a bylaw, but whether the present use is, in substance, the same as it was in 1973.<br />

Setting aside for the moment the issue of degree, in my view the answer is yes. The trial judge found<br />

as a fact, amply supported by evidence, that "[f]riends and relatives of the owners have brought<br />

tents, trailers and recreation vehicles onto the property every year since it was first purchased in<br />

1969". The evidence establishes that the present owners use the trailer, still <strong>ca</strong>pable of road use,<br />

and that friends bring recreational vehicles and tents onto the property....Here, on the findings of fact<br />

by the trial judge, supported by the evidence, this lot was a "private <strong>ca</strong>mping site" available for all<br />

degrees of <strong>ca</strong>mping in 1973 to family and friends of the owners and it remains so today. That being<br />

the <strong>ca</strong>se, one <strong>ca</strong>nnot say there has been a discontinuance of that use so as to sever the legality of<br />

the non-conforming use under s. 911(1) of the Act. (emphasis added)<br />

Discussion<br />

[122] The defendants submit that they have continued their use since the summer of 2005. The defendants<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

contend that the “use” protected by s. 911 of the LGA is the “broad use” to which the property has been put,<br />

not the individual acts that make up that broad use. They maintain that they were not required to rent out the<br />

Property in exactly the same fashion and frequency every year. They simply must show that since 2005 the<br />

Property has been continuously used as a rental property in the same general manner. The defendants say<br />

that there has been continuous use in the broader sense since 2005, which includes the period in 2010 when<br />

the renovations were undertaken and the Property was not rented.<br />

[123] They rely on Cowichan Valley (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Ward (1994), 39 B.C.A.C. 154, where the Court of<br />

Appeal held that, although the sawmill property was not always running and had been subject to<br />

maintenance from time to time, the use was nonetheless protected under the provisions for lawful nonconforming<br />

use.<br />

[124] In my opinion, the fact that the defendants rented out the Property only during the summer months<br />

does not mean that the use was discontinued. This position accords with the plain wording of s. 911(2)(a) of<br />

the LGA, which provides that a seasonal use of land is not discontinued as a result of normal seasonal<br />

practices, including seasonal or market cycles. Moreover, it emerges from the jurisprudence that it is the<br />

actual use in the general sense that matters with respect to the continuance of lawful non-conforming use.<br />

As with the summer <strong>ca</strong>mping in Nobbs, short-term rentals during certain weeks in the summer months were<br />

part of the general status quo over the years. The Property was actually rented out for approximately five<br />

weeks out of the year, used by the defendants and their friends or family for one to three months per year,<br />

and va<strong>ca</strong>nt for much of the year.<br />

[125] However, there remains the issue of whether the defendants’ renovations, which commenced in 2009<br />

and included the addition of a bathroom and 33 square feet of floor space, terminated the lawful nonconforming<br />

use.<br />

[126] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> submits that the defendants’ comprehensive renovations to the Property have<br />

terminated the lawful non-conforming use pursuant to s. 911(8) of the LGA. That section provides that if a<br />

building that is being used for a non-conforming purpose is damaged or destroyed to the extent of 75% or<br />

more of its value above its foundations, as determined by the building inspector, it must not be repaired or<br />

reconstructed except for a conforming use in accordance with the bylaw. However, the evidence does not<br />

establish that the Property was damaged or destroyed to the extent of 75% or more of its value above its<br />

foundation, as determined by the building inspector. I conclude, therefore, that s. 911(8) of the LGA is not<br />

appli<strong>ca</strong>ble.<br />

[127] The defendants submit that the renovation to the Property included upgrades to the plumbing, heating,<br />

and electri<strong>ca</strong>l system, all of which were needed to comply with modern codes to protect the health and safety<br />

of the occupants of the Property. They contend that the renovations fall within s. 911(2)(c) of the LGA, which<br />

provides that a use is not discontinued as a result of repairs to meet health and safety standards.<br />

[128] However, in my opinion, s. 911(2)(c) is not appli<strong>ca</strong>ble be<strong>ca</strong>use the section clearly refers to repair,<br />

replacement or installation of equipment. The record does not establish that the renovations undertaken by<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

the defendants pertain to equipment.<br />

[129] I turn to address whether the renovations undertaken by the defendants constituted a structural<br />

addition pursuant to s. 911(5), which provides as follows:<br />

(5). A structural alteration or addition, except one that is required by an enactment or permitted<br />

by a board of variance under section 901 (2), must not be made in or to a building or other structure<br />

while the non-conforming use is continued in all or any part of it. (emphasis added)<br />

[130] Mr. Leach testified in his examination for discovery that the renovations to the Property were<br />

undertaken due to a leaky roof, which was replaced, and that replacement and upgrades were required to<br />

meet modern building codes. As referred to earlier, a bathroom was added and the house in total was<br />

expanded by 33 square feet. Two interior walls and the underlying foundations were changed. Mr. Leach<br />

deposed as follows:<br />

28. The renovation and refurbishment included updated electri<strong>ca</strong>l wiring to meet current code<br />

requirements, plumbing upgrades, replacement of all mechani<strong>ca</strong>l HVAC components, utility upgrades<br />

and general finishing. The replacements and upgrades all need to be completed to modern codes for<br />

building, electri<strong>ca</strong>l and plumbing.<br />

[131] The defendants’ uncontradicted evidence is that the replacement of the roof was required by the<br />

appli<strong>ca</strong>ble building codes and that the replacement and upgrades were required for compliance with the<br />

modern electri<strong>ca</strong>l, plumbing, and building codes. The evidence does not show, and I <strong>ca</strong>nnot accept, that the<br />

addition of a new bathroom constitutes either a replacement or an upgrade that was required to meet current<br />

code requirements. The evidence does not show that this structural addition or alteration was permitted by a<br />

board of variance. I conclude, therefore, that the addition of a new bathroom constitutes a structural alteration<br />

or addition which is prohibited by the provisions of s. 911(5).<br />

[132] In the result, with respect to the 1995 Zoning Bylaw the defendants have failed to establish that they<br />

meet the criteria for lawful non-conforming use.<br />

[133] In view of my findings, it is not necessary to address the <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>’s submission that the<br />

defendants did not continue the operation of the Va<strong>ca</strong>tion Rentals, either after the renovations or following<br />

the commencement of these proceedings.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

[134] The <strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong> has failed to show that the defendants are utilizing the Property in breach of the<br />

2008 Zoning Bylaw. As a result, I need not consider the issue of the appropriate remedy. The <strong>Regional</strong><br />

<strong>District</strong>’s appli<strong>ca</strong>tion is therefore dismissed.<br />

COSTS<br />

[135] Counsel have requested the opportunity to make submissions on costs following the delivery of these<br />

reasons for judgment. If the parties are unable to resolve the issue of costs, they may reserve a date through<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]

2012 BCSC 63 <strong>Okanagan</strong>-<strong>Similkameen</strong> (<strong>Regional</strong> <strong>District</strong>) v. Leach<br />

Supreme Court Scheduling to address the issue.<br />

_________ “Dardi J.”______________<br />

Dardi, J.<br />

http://www.courts.gov.<strong>bc</strong>.<strong>ca</strong>/jdb-txt/SC/12/00/2012BCSC0063cor1.htm[03/29/2012 10:23:44 AM]