Journal of Tehran University Heart Center

Journal of Tehran University Heart Center

Journal of Tehran University Heart Center

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Zohair Yousef Al-halees, MD , FRCSC, FACS<br />

King Faisal <strong>Heart</strong> Institute, Saudi Arabia<br />

Yadolah Dodge, PhD<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Neuchâtel, Switzerland<br />

Ali Dodge-Khatami, MD, PhD<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Hamburg-Eppendorf School <strong>of</strong> Medicne, Germany<br />

Iradj Gandjbakhch, MD<br />

Hopital Pitie, France<br />

Omer Isik, MD<br />

Yeditepe <strong>University</strong>, School <strong>of</strong> Medicine, Turkey<br />

Sami S. Kabbani, MD<br />

Damascus <strong>University</strong> Cardiovascular Surgical <strong>Center</strong>, Syria<br />

Kayvan Kamalvand, MD, FRCP, FACC<br />

William Harvey Hospital, United Kingdom<br />

Jean Marco, MD, FESC<br />

Centre Cardio- Thoracique de Monaco, France<br />

Ali Massumi, MD<br />

Texas <strong>Heart</strong> Institute, U. S. A<br />

Carlos-A. Mestres, MD<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Barcelona, Spain<br />

Hossien Ahmadi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Shahin Akhondzadeh, PhD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mohammad Alidoosti, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mohammad Ali Boroumand, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Ahmad Reza Dehpour, PhD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Abbasali Karimi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Seyed Ebrahim Kassaian, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Davood Kazemi Saleh, MD<br />

Baghiatallah <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Majid Maleki, MD<br />

Iran <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mehrab Marzban, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mansor Moghadam, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Sina Moradmand Badie, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Seyed Mahmood Mirhoseini, MD, DSc, FACC, FAES<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

THE<br />

JOURNAL OF TEHRAN<br />

UNIVERSITY HEART<br />

CENTER<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

ABBASALI KARIMI, MD<br />

PROFESSOR OF CARDIAC SURGERY<br />

TEHRAN UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES<br />

Managing Editor<br />

SEYED HESAMEDDIN ABBASI, MD<br />

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

TEHRAN UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL SCIENCES<br />

International Editors<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Fred Morady, MD<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Michigan, U. S. A<br />

Mohammed T. Numan, MD<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Texas, U. S. A<br />

Ahmand S. Omran, MD, FACC, FASE<br />

King Abdulaziz Cardiac <strong>Center</strong>, Saudi Arabia<br />

Fausto J. Pinto, MD, PhD, FESC, FACC, FASA, FSCAI,<br />

FASE<br />

Lisbon <strong>University</strong>, Portugal<br />

Mehrdad Rezaee, MD, PhD<br />

Stanford <strong>University</strong>, School <strong>of</strong> Medicine, U. S. A<br />

Gregory S. Thomas, MD, MPH, FACC, FACP, FASNC<br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> California, U. S. A<br />

Lee Samuel Wann, MD<br />

Wisconsin <strong>Heart</strong> Hospital, U. S. A<br />

Hein J. Wellens, MD<br />

Cardiovascular Research Institute, Maastricht, The Netherlands<br />

Douglas P. Zipes, MD<br />

Indiana <strong>University</strong>, School <strong>of</strong> medicine, U. S. A<br />

Seyed Rasoul Mirsharifi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Ahmad Mohebi, MD<br />

Iran <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mohammad-Hasan Namazi<br />

Shaheed beheshti <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Ebrahim Nematipour, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Rezayat Parvizi, MD<br />

Tabriz <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Masoud Pezeshkian<br />

Tabriz <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Hassan Radmehr, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Saeed Sadeghian, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mojtaba Salarifar, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Nizal Sarraf –Zadegan, MD<br />

Isfahan <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Ahmad Yaminisharif, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mohammad Reza Zafarghandi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Aliakbar Zeinaloo, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences

Advisory Board<br />

Kiyomars Abbasi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Seifollah Abdi, MD<br />

Iran <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Alireza Amirzadegan, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Naser Aslanabadi, MD<br />

Tabriz <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Sirous Darabian, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Gholamreza Davoodi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Saeed Davoodi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Iraj Firoozi, MD<br />

Iran <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Seyed Khalil Foroozannia, MD<br />

Shaheed Sadoghi <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Armen Gasparyan MD, PhD<br />

Armenia<br />

Ali Ghaemian, MD<br />

Mazandaran <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Namvar Ghasemi Movahedi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Abbas Ghiasi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Ali Kazemi Saeed, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Ali Mohammad Haji Zeinali, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mohammad Jafar Hashemi, MD<br />

Iran <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mahmood Sheikh Fathollahi<br />

Pedram Amouzadeh<br />

Fatemeh Esmaeili Darabi<br />

Seyed Kianoosh Hoseini<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Elise Langdon- Neuner<br />

The editor <strong>of</strong> The Write Stuff, Austria<br />

Jalil Majd Ardekani, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Fardin Mirbolook, MD<br />

Gilan <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mehdi Najafi, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Younes Nozari, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Hamid Reza Pour Hosseini, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Hakimeh Sadeghian, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mohammad Saheb Jam, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Abbas Salehi Omran, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Mahmood Shabestari, MD<br />

Mashhad <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Shapour Shirani, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Abbas Soleimani, MD<br />

Kerman <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Seyed Abdolhosein Tabatabaei, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Murat Ugurlucan, MD<br />

Rostock <strong>University</strong> Medical Faculty<br />

Arezou Zoroufian, MD<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences<br />

Statistical Consultant<br />

Technical Editors<br />

Graphic Design & Office<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong> is indexed in Scopus, EMBASE, CAB Abstracts, Global Health,<br />

Chemical Abstract Service, Cinahl, Google Scholar, DOAJ, Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and<br />

Research, Index Copernicus, Index Medicus for the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (IMEMR), ISC, SID,<br />

Iranmedex and Magiran<br />

Address<br />

North Kargar Street, <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>, <strong>Tehran</strong>, Iran 1411713138. Tel: +98-21-88029720. Fax: +98-21-88029702.<br />

Web Site: http://jthc.tums.ac.ir. E-mail: jthc@tums.ac.ir.

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

Content<br />

Volume: 6 Number: 2 Spring 2011<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Review Article<br />

Cardiovascular Effects <strong>of</strong> Saffron: An Evidence-Based Review<br />

Maryam Kamalipour, Shahin Akhondzadeh …………….................................................................................................................................................... 59<br />

Original Articles<br />

Demographics and Angiographic Findings in Patients under 35 Years <strong>of</strong> Age with Acute ST Elevation Myocardial<br />

Infarction<br />

Seyed Kianoosh Hosseini, Abbas Soleimani, Mojtaba Salarifar, Hamidreza Pourhoseini, Ebrahim Nematipoor, Seyed Hesameddin Abbasi, Ali Abbasi ...... 62<br />

Signal-Averaged Electrocardiography in Patients with Advanced <strong>Heart</strong> Failure: A Better Indicator <strong>of</strong> Left<br />

Ventricular Enlargement Compared with Conventional Electrocardiography<br />

Mohammad Alasti, Majid Haghjoo, Abolfath Alizadeh, Mohammad Hossein Nikoo, Hamid Reza Bonakdar, Bita Omidvar .......................................... 68<br />

Carotid Artery Wall Motion Estimation from Consecutive Ultrasonic Images: Comparison <strong>of</strong> Block Matching and<br />

Maximum Gradient Algorithms<br />

Effat Soleimani, Manijhe Mokhtari-Dizaji, Hajir Saberi .................................................................................................................................................... 72<br />

Transcatheter Closure <strong>of</strong> Atrial Septal Defect with Amplatzer Septal Occluder in Adults: Immediate, Short, and<br />

Intermediate-Term Results<br />

Mostafa Behjati, Mansour Rafiei, Mohammad Hossein Soltani, Mahmoud Emami, Majid Dehghani ................................................................ 79<br />

Case Reports<br />

Incidental Finding <strong>of</strong> Cor Triatriatum Sinistrum in a Middle-Aged Man Candidated for Coronary Bypass Grafting<br />

(with Three-D Imaging)<br />

Afsoon Fazlinezhad, Farveh Vakilian, Asadollah Mirzaei, Azadeh Fallah Rastegar ……................................................................................................... 85<br />

Segmented Coronary Artery Aneurysms and Kawasaki Disease<br />

Mohammad Yoosef Aarabi Moghadam, Hojat Mortazaeian, Mehdi Ghaderian, Hamid Reza Ghaemi ……..…................................................................ 89<br />

Traumatic Left Anterior Descending Coronary Artery-Right Ventricle Fistula: A Case Report<br />

Mohammad Ali Sheikhi, Mehdi Asgari, Mehdi Dehghani Firouzabadi, Mohammad Reza Zeraati, Alireza Rezaee...……….............................……..… 92<br />

Letter to the Editor<br />

Percutaneous Revascularization <strong>of</strong> Patients with History <strong>of</strong> Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting<br />

Seyed Kianoosh Hoseini, Fatemeh Behboudi ………………………………………………..……………….......................................……....….....…… 95<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

Review Article<br />

Cardiovascular Effects <strong>of</strong> Saffron: An Evidence-Based<br />

Review<br />

Maryam Kamalipour, MSc, Shahin Akhondzadeh, PhD, FBPharmacolS *<br />

Roozbeh Psychiatric Hospital, <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, <strong>Tehran</strong>, Iran.<br />

Received 15 January 2011; Accepted 28 March 2011<br />

Abstract<br />

Herbal medicine can be a valuable source <strong>of</strong> assistance for traditional medicine. There are a number <strong>of</strong> herbs that can be<br />

used in conjunction with modern medicine. Herbs can also be taken to aid recovery from serious diseases. Although one should<br />

never aim to treat diseases such as cardiovascular disease solely with herbal medicine, the value <strong>of</strong> herbs used in tandem with<br />

modern medicine cannot be ignored. Saffron has been reported to help lower cholesterol and keep cholesterol levels healthy.<br />

Animal studies have shown saffron to lower cholesterol by as much as 50%. Saffron has antioxidant properties; it is, therefore,<br />

helpful in maintaining healthy arteries and blood vessels. Saffron is also known to have anti-inflammatory properties, which<br />

are beneficial to cardiovascular health. The people <strong>of</strong> Mediterranean countries, where saffron use is common, have lower<br />

than normal incidence <strong>of</strong> heart diseases. From saffron's cholesterol lowering benefits to its anti inflammatory properties,<br />

saffron may be one <strong>of</strong> the best supplements for cardiac health. This paper reviews the studies regarding the beneficial effects<br />

<strong>of</strong> saffron in cardiovascular health.<br />

J Teh Univ <strong>Heart</strong> Ctr 2011;6(2):59-61<br />

This paper should be cited as: Kamalipour M, Akhondzadeh S. Cardiovascular Effects <strong>of</strong> Saffron: An Evidence-Based Review. J<br />

Teh Univ <strong>Heart</strong> Ctr 2011;6(2):59-61.<br />

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory agents, non-steriodal • Cardiovascular agents • Lipid regulating agents • Crocus sativus<br />

Introduction<br />

The role <strong>of</strong> alternative medicine in general and<br />

phytotherapy in various diseases in particular has been <strong>of</strong><br />

extreme interest to various scientific and non-scientific<br />

communities throughout the world. Phytotherapy is broadly<br />

defined as the use <strong>of</strong> natural therapeutic agents derived from<br />

plants or crude herbal drugs. Herbal medicine has a long and<br />

respected history and holds a valuable place in the treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> cardiovascular diseases as well as the vast majority <strong>of</strong><br />

health problems. Utilizing the leaves, flowers, stems, berries,<br />

and roots <strong>of</strong> plants to both prevent and treat illness, herbal<br />

medicine not only helps to alleviate symptoms but also helps<br />

to treat the underlying problem, as well as strengthen the<br />

overall functioning <strong>of</strong> a particular organ or body system. 1, 2<br />

Cardiovascular diseases are now considered a major cause<br />

<strong>of</strong> mortality not only in the developed world but also in the<br />

developing countries. In the age <strong>of</strong> genomics, nanotechnology,<br />

and proteomics, cardiovascular diseases continue to remain<br />

a major challenge to therapeutically manage; and the search<br />

for a viable evidence-based alternative continues.<br />

Saffron (Crocis sativus) is a spice derived from the flower<br />

<strong>of</strong> the saffron crocus (Crocus sativus), a species <strong>of</strong> crocus in<br />

the family Iridaceae. The flower has three stigmas, which<br />

are the distal ends <strong>of</strong> the plant’s carpels. Together with its<br />

style, the stalk connecting the stigmas to the rest <strong>of</strong> the plant,<br />

*<br />

Corresponding Author: Shahin Akhondzadeh, Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Neuroscience, Psychiatric Research <strong>Center</strong>, Roozbeh Psychiatric Hospital, <strong>Tehran</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, South Kargar Street, <strong>Tehran</strong>, Iran. 13337. Tel: +98 21 88281866, Fax: +98 21 55419113. E-mail: s.akhond@neda.net.<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong> 59

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Shahin Akhondzadeh et al.<br />

these components are <strong>of</strong>ten dried and used in cooking as a<br />

seasoning and coloring agent. Saffron, which has for decades<br />

been the world’s most expensive spice by weight, is native to<br />

Iran; it was first cultivated in the Persian Empire. 2, 3 Saffron<br />

is characterized by a bitter taste and an iod<strong>of</strong>orm- or haylike<br />

fragrance; these are caused by the chemicals picrocrocin<br />

and safranal. It also contains a carotenoid dye, crocin, which<br />

gives food a rich golden-yellow hue. These traits make<br />

saffron a much-sought ingredient in many foods worldwide.<br />

Saffron also has medicinal applications. 3, 4<br />

Saffron tastes bitter and contributes a luminous yelloworange<br />

coloring to foods. Because <strong>of</strong> the unusual taste and<br />

coloring it adds to foods, saffron is widely used in Persian,<br />

Arab, Central Asian, European, Indian, Moroccan, and<br />

Cornish cuisines. Confectionaries and liquors also <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

include saffron. Medicinally, saffron has a long history as part<br />

<strong>of</strong> traditional healing; modern medicine has also discovered<br />

saffron as having anticarcinogenic (cancer-suppressing),<br />

anti-mutagenic (mutation-preventing), immuno-modulating,<br />

and antioxidant-like properties. Saffron has also been<br />

used as a fabric dye, particularly in China and India, and<br />

in perfumery. 1, 2 Recent studies have shown the beneficial<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> saffron in depression, premenstrual syndrome<br />

(PMS), and Alzheimer’s Disease. 3-9<br />

Saffron and <strong>Heart</strong> Disease Protection<br />

Antioxidants in saffron tea can reduce the risk <strong>of</strong><br />

cardiovascular diseases. The flavonoids, especially lycopene,<br />

found in saffron can provide added protection. A clinical trial<br />

at the Department <strong>of</strong> Medicine and Indigenous Drug Research<br />

<strong>Center</strong> showed positive effects <strong>of</strong> saffron on cardiovascular<br />

diseases. 10 The study involved 20 participants, including<br />

10 with heart diseases. According to the Indian <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Medical Sciences, all the participants showed improved<br />

health, but those with cardiovascular diseases showed more<br />

progress. In addition, saffron has been found to be the richest<br />

source <strong>of</strong> rib<strong>of</strong>lavin. 1, 2 Due to the presence <strong>of</strong> crocetin, it<br />

indirectly helps to reduce cholesterol level in the blood<br />

and severity <strong>of</strong> atherosclerosis, thus reducing the chances<br />

<strong>of</strong> heart attacks. It may be one <strong>of</strong> the prime reasons that in<br />

Spain, where Saffron is consumed liberally, the incidence <strong>of</strong><br />

cardiovascular diseases is quite low. The crocetin present in<br />

saffron is found to increase the yield <strong>of</strong> antibiotics. 11 Two<br />

compounds <strong>of</strong> safranal are supposed to increase antibacterial<br />

and antiviral physiological activity in the body. 12<br />

In 2005, Zheng et al. administered crocetin, the natural<br />

carotenoid antioxidant, to rabbits to determine its effect on<br />

the development <strong>of</strong> atherosclerosis. The authors randomly<br />

assigned New Zealand white rabbits to three different diets<br />

for eight weeks: a standard diet, a high lipid diet (HLD),<br />

or a high lipid + crocetin diet. The HLD group developed<br />

hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis, while the<br />

crocetin-supplemented group decreased the negative health<br />

effects <strong>of</strong> a high lipid diet. 13 The results did not show a<br />

significant difference in the plasma lipid levels (total, low<br />

density lipoprotein (LDL), and high density lipoprotein<br />

(HDL) cholesterol) between the HLD and crocetin groups<br />

but did show a significant decrease in the aorta cholesterol<br />

deposits, atheroma, foam cells, and atherosclerotic lesions<br />

in the crocetin-fed group. They suggested that nuclear factor<br />

kappa B (NF-κB) activation in the aortas is suppressed by<br />

antioxidants such as crocetin which in turn decreases the<br />

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression. 13<br />

A 2006 study by Sheng and colleagues looked at<br />

an alternative mechanism for crocin’s atherosclerotic<br />

properties. 14 Crocin inhibited an increase in serum<br />

triglycerides, total-, LDL-, cholesterol compared to the<br />

control group as seen before; however, the results also<br />

showed a significant increase in the fecal excretion <strong>of</strong> fat<br />

and cholesterol in the crocin group (100 mg/kg/day). 14<br />

Further studies determined that crocin inhibited pancreatic<br />

and gastric lipase activity, although a potential mechanism<br />

was not <strong>of</strong>fered. Since pancreatic lipase is responsible for fat<br />

absorption by hydrolyzing fat, the inhibition <strong>of</strong> pancreatic<br />

lipase activity resulted in low lipid absorption. With a lack<br />

<strong>of</strong> potential pancreatic lipase inhibitors available, crocin<br />

shows promise as a drug for treating hyperlipidemia. 14<br />

In conclusion, saffron helps reduce the risk <strong>of</strong> heart<br />

diseases by strengthening the blood circulatory system. Rich<br />

in minerals like thiamin and rib<strong>of</strong>lavin, saffron promotes a<br />

healthy heart and prevents different cardiac problems.<br />

References<br />

1. Schmidt M, Betti G, Hensel A. Saffron in phytotherapy:<br />

pharmacology and clinical uses. Wien Med Wochenschr<br />

2007;157:315-319.<br />

2. Bathaie SZ, Mousavi SZ. New applications and mechanisms <strong>of</strong><br />

action <strong>of</strong> saffron and its important ingredients. Crit Rev Food Sci<br />

Nutr 2010;50:761-786.<br />

3. Akhondzadeh S, Tahmacebi-Pour N, Noorbala AA, Amini H, Fallah-<br />

Pour H, Jamshidi AH, Khani M. Crocus sativus L. in the treatment<br />

<strong>of</strong> mild to moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized and<br />

placebo controlled trial. Phytother Res 2005;19:148-151.<br />

4. Noorbala AA, Akhondzadeh S, Tahmacebi-Pour N, Jamshidi AH.<br />

Hydroalcoholic extract <strong>of</strong> Crocus sativus L. versus fluoxetine<br />

in the treatment <strong>of</strong> mild to moderate depression: a double-blind,<br />

randomized pilot trial. J Ethnopharmacol 2005;97:281-284.<br />

5. Moshiri E, Basti AA, Noorbala AA, Jamshidi AH, Abbasi S,<br />

Akhondzadeh SH. Crocus sativus L. (petal) in the treatment <strong>of</strong><br />

mild-to-moderate depression: a double-blind, randomized and<br />

placebo controlled trial. Phytomedicine 2006;13:607-611.<br />

6. Akhondzadeh Basti A, Moshiri E, Noorbala AA, Jamshidi AH,<br />

Abbasi SH, Akhondzadeh S. Comparison <strong>of</strong> petal <strong>of</strong> Crocus sativus<br />

L. and fluoxetine in the treatment <strong>of</strong> depressed outpatients: a pilot<br />

double-blind randomized trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol<br />

Psychiatry 2007;31:439-442.<br />

7. Agha-Hosseini M, Kashani L, Aleyaseen A, Ghoreishi A,<br />

Rahmanpour H, Zarrinara AR, Akhondzadeh S. Crocus sativus L.<br />

(saffron) in the treatment <strong>of</strong> premenstrual syndrome: a double-blind,<br />

randomised and placebo controlled trial. BJOG 2008;115:515-<br />

519.<br />

60

Cardiovascular Effects <strong>of</strong> Saffron: An Evidence-Based Review<br />

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

8. Akhondzadeh S, Sabet MS, Harirchian MH, Togha M,<br />

Cheraghmakani H, Razeghi S, Hejazi SS, Yousefi MH, Alimardani<br />

R, Jamshidi A, Zare F, Moradi A. Saffron in the treatment <strong>of</strong> patients<br />

with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a 16-week, randomized<br />

and placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther 2010;35:581-588.<br />

9. Akhondzadeh S, Shafiee Sabet M, Harirchian MH, Togha M,<br />

Cheraghmakani H, Razeghi S, Hejazi SS, Yousefi MH, Alimardani<br />

R, Jamshidi A, Rezazadeh SA, Yousefi A, Zare F, Moradi A,<br />

Vossoughi A. A 22-week, multicenter, randomized, doubleblind<br />

controlled trial <strong>of</strong> Crocus sativus in the treatment <strong>of</strong> mildto-moderate<br />

Alzheimer’s disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl)<br />

2010;207:637-643.<br />

10. Verma SK, Bordia A. Antioxidant property <strong>of</strong> Saffron in man.<br />

Indian J Med Sci 1998;52:205-207.<br />

11. Basker D, Negbi M. The use <strong>of</strong> saffron. Econ Bot 1983;37:228-<br />

236.<br />

12. Zarghami NS, Heinz DE. Monoterpene aldehydes and isophorone<br />

337 related compounds <strong>of</strong> saffron. Phytochemistry 1971;10:2755-<br />

2761.<br />

13. Zheng S, Qian Z, Tang F, Sheng L. Suppression <strong>of</strong> vascular<br />

cell adhesion molecule-1 expression by crocetin contributes to<br />

attenuation <strong>of</strong> atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic rabbits.<br />

Biochem Pharmacol 2005;70:1192-1199.<br />

14. Sheng L, Qian Z, Zheng S, Xi L. Mechanism <strong>of</strong> hypolipidemic<br />

effect <strong>of</strong> crocin in rats: crocin inhibits pancreatic lipase. Eur J<br />

Pharmacol 2006;543:116-122.<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>61

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Original Article<br />

Demographics and Angiographic Findings in Patients<br />

under 35 Years <strong>of</strong> Age with Acute ST Elevation Myocardial<br />

Infarction<br />

Seyed Kianoosh Hosseini, MD 1 , Abbas Soleimani, MD 1 , Mojtaba Salarifar,<br />

MD 1* , Hamidreza Pourhoseini, MD 1 , Ebrahim Nematipoor, MD 1 , Seyed<br />

Hesameddin Abbasi, MD 1, 2 , Ali Abbasi, MD 3<br />

1<br />

<strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>, <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, <strong>Tehran</strong>, Iran.<br />

2<br />

Family Health Research <strong>Center</strong>, Iranian Petroleum Industry Health Research Institute, <strong>Tehran</strong>, Iran.<br />

3<br />

<strong>University</strong> Medical <strong>Center</strong> Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands.<br />

Received 23 September 2010; Accepted 18 January 2011<br />

Abstract<br />

Background: ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a major cause <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular mortality worldwide.<br />

There are differences between very young patients with STEMI and their older counterparts. This study investigates the<br />

demographics and clinical findings in very young patients with STEMI.<br />

Methods: Through a review <strong>of</strong> the angiography registry, 108 patients aged ≤ 35 years (Group I) were compared with 5544<br />

patients aged > 35 years (Group II) who underwent coronary angiography after STEMI.<br />

Results: Group I patients were more likely to be male (92.6%), smokers, and have a family history <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular<br />

diseases (34.6%). The prevalence <strong>of</strong> diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension was higher in the old patients. Triglyceride<br />

and hemoglobin were significantly higher in Group I. Normal coronary angiogram was reported in 18.5% <strong>of</strong> the young<br />

patients, and in 2.1% <strong>of</strong> the older patients. The prevalence <strong>of</strong> single-vessel and multi-vessel coronary artery disease was<br />

similar in the two groups (34.3% vs. 35.2%). The younger subjects were more commonly candidates for medical treatment<br />

and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (84.2%), while coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) was considered for<br />

the 39.5% <strong>of</strong> their older counterparts.<br />

Conclusion: In the young adults with STEMI, male gender, smoking, family history, and high triglyceride level were more<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten observed. A considerable proportion <strong>of</strong> the young patients presented with multi-vessel coronary disease. PCI or medical<br />

treatment was the preferred treatment in the younger patients; in contrast to their older counterparts, in whom CABG was<br />

more commonly chosen for revascularization.<br />

J Teh Univ <strong>Heart</strong> Ctr 2011;6(2):62-67<br />

This paper should be cited as: Hosseini SK, Soleimani A, Salarifar M, Pourhoseini H, Nematipoor E, Abbasi SH, Abbasi A.<br />

Demographics and Angiographic Findings in Patients under 35 Years <strong>of</strong> Age with Acute ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Teh Univ<br />

<strong>Heart</strong> Ctr 2011;6(2):62-67.<br />

Keywords: Myocardial infarction • Young adult • Coronary angiography • Risk factors<br />

*<br />

Corresponding Author: Mojtaba Salarifar, Assistant Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Interventional Cardiology, Cardiology Department, <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>, North<br />

Kargar Street, <strong>Tehran</strong>, Iran. 1411713138. Tel: +98 21 88029257. Fax: +98 21 88029256. E-mail: salarifar@tehranheartcenter.org.<br />

62

Demographics and Angiographic Findings in Patients under 35 Years <strong>of</strong> ...<br />

Introduction<br />

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is<br />

one <strong>of</strong> the most common causes <strong>of</strong> emergency department<br />

admissions and cardiovascular mortalities and thus currently<br />

accounts for a high burden on health care services in the<br />

world. Although STEMI is an uncommon entity in young<br />

patients, it has always attracted special attention because<br />

<strong>of</strong> its unusual features and devastating effect on their more<br />

active lifestyle. 1-5<br />

In recent years, whereas the mean age <strong>of</strong> coronary artery<br />

disease (CAD) has decreased, its prevalence seems to have<br />

been on the increase. 4 A number <strong>of</strong> studies, including our<br />

previous report, have shown significant differences in the risk<br />

factor pr<strong>of</strong>ile and coronary angiographic patterns between<br />

young and older patients with acute STEMI. 1-3, 6-8 Traditional<br />

risk factors <strong>of</strong> CAD are prevalent in young patients with<br />

acute STEMI but with a different pattern compared to their<br />

older counterparts; these differences may cause different<br />

treatment strategies and outcome among these patients. 3,<br />

5, 9<br />

There is evidence that a concentration <strong>of</strong> the novel risk<br />

factors <strong>of</strong> CAD such as LP (a) may be higher than normal in<br />

the <strong>of</strong>fspring <strong>of</strong> patients with a history <strong>of</strong> premature MI. 10<br />

There is a dearth <strong>of</strong> available data on very young adults with<br />

STEMI, as a life-threatening cardiac emergency condition.<br />

In an attempt to characterize patients 35 years <strong>of</strong> age or<br />

younger suffering STEMI, we reviewed the <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>Heart</strong><br />

<strong>Center</strong> Angiography Registry (THCAR) and compared the<br />

demographics and clinical findings <strong>of</strong> these patients to those<br />

older than 35 years <strong>of</strong> age.<br />

Methods<br />

From all the patients admitted by cardiologists between<br />

January 2000 and March 2008 to the Angiography<br />

Department affiliated with the Academic <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>,<br />

we identified 5652 patients with a history <strong>of</strong> STEMI. The<br />

databank contains patients’ data collected by cardiologists and<br />

trained general practitioners, and the validity <strong>of</strong> all the data<br />

is checked by reabstracting 10% <strong>of</strong> the patients’ entries and<br />

by reentering 5% <strong>of</strong> the patients' records. The investigation<br />

was approved by the institutional Review Board, overseeing<br />

the participation <strong>of</strong> human subjects in research at <strong>Tehran</strong><br />

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences. This study conforms to the<br />

principles outlined in the Declaration <strong>of</strong> Helsinki.<br />

The validation <strong>of</strong> acute myocardial infarction (AMI) events<br />

was based on information on medical history, symptoms,<br />

electrocardiogram, and cardiac enzymes. STEMI was<br />

diagnosed when new or presumed new ST-segment elevation<br />

≥ 1 mm ( ≥ 2 mm in V 1<br />

to V 3<br />

) was seen in any location in two<br />

or more contiguous leads or new left bundle branch block<br />

was found on the index or qualifying electrocardiogram<br />

with ≥ 1 positive cardiac biochemical marker <strong>of</strong> necrosis<br />

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

(including CKMB-mass or quantitative cardiac troponin<br />

measurements). The cardiologist who performed the coronary<br />

angiography documented and recorded STEMI diagnosis<br />

in the datasheets. Coronary angiography was performed in<br />

almost all the patients as part <strong>of</strong> the pharmacoinvasive strategy<br />

or as the primary treatment option (primary percutaneous<br />

coronary intervention [PCI]) based on the American College<br />

<strong>of</strong> Cardiology/American <strong>Heart</strong> Association (ACC/AHA)<br />

Guidelines for the management <strong>of</strong> patients with STEMI. 11 To<br />

characterize the young patients, the patients were divided into<br />

2 subgroups <strong>of</strong> ≤ 35 years (Group I, n = 108) and those older<br />

than 35 years (Group II, n = 5544). The following data were<br />

included for analysis: demographic data (i.e. age and gender)<br />

and CAD risk factor pr<strong>of</strong>ile, comprised <strong>of</strong> current cigarette<br />

smoking history (patient regularly smokes a tobacco product/<br />

products one or more times per day or has smoked in the 30<br />

days prior to admission), hyperlipidemia (total cholesterol ≥<br />

5.0, HDL-cholesterol ≤ 1.0 in men or ≤ 1.1 in women, and<br />

triglycerides ≥ 2.0 mmol/l), family history <strong>of</strong> CAD (firstdegree<br />

relatives before the age <strong>of</strong> 55 in men and 65 years in<br />

women), hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 and/or<br />

diastolic ≥ 90 mmHg and/or on anti-hypertensive treatment),<br />

diabetes mellitus (symptoms <strong>of</strong> diabetes and plasma glucose<br />

concentration ≥ 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l), or fasting blood<br />

sugar (FBS) ≥ 126 mg/dl (7.0mmol/l) or 2-hp ≥ 200 mg/dl<br />

(11.1 mmol/l)), and opium consumption. 12<br />

Clinical manifestations, left ventricular ejection fraction<br />

(LVEF), hematologic indices, coronary angiographic findings,<br />

and treatment strategy were reported. Selective coronary<br />

arteriography was performed using standard technique in<br />

all the patients. Significant CAD was defined as a diameter<br />

stenosis > 50% in each major epicardial artery. A narrowing<br />

<strong>of</strong> < 50% was considered mild CAD. Normal vessels were<br />

defined as the complete absence <strong>of</strong> any disease in the left<br />

main coronary artery (LMCA), left anterior descending<br />

(LAD), right coronary artery (RCA), and left circumflex<br />

(LCx) as well as in their main branches (diagonal, obtuse<br />

marginal, ramus intermedius, posterior descending artery,<br />

and posterolateral branch). Even mild luminal irregularities<br />

were regarded as evidence <strong>of</strong> atherosclerosis.<br />

The results were reported as mean ± standard deviation<br />

(SD) for the quantitative variables and percentages for the<br />

categorical variables. The groups were compared using the<br />

Student t-test for the continuous variables and the Chi-square<br />

test for the dichotomous variables. This study was done with<br />

the power <strong>of</strong> 90%. P values <strong>of</strong> 0.05 or less were considered<br />

statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were<br />

carried out via Statistical Package for Social Sciences version<br />

16 (SPSS, IL, Chicago Inc., USA).<br />

Results<br />

The demographic and historical characteristics <strong>of</strong> the study<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>63

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Seyed Kianoosh Hosseini et al.<br />

population are listed in Table 1. The mean patient age was 56.7<br />

± 10.8 (Range: 17-95) years. The male patients accounted<br />

for 79.8% <strong>of</strong> the total study population. The risk factors<br />

included smoking in 30.8% <strong>of</strong> the cases, hyperlipidemia in<br />

59.4%, diabetes in 27.4%, and hypertension in 40.8% with<br />

an average body mass index (BMI) <strong>of</strong> 27.6 ± 4.4 kg/m 2 in<br />

this population. A family history <strong>of</strong> CAD was reported in<br />

24.2% <strong>of</strong> the patients. Use <strong>of</strong> opium as a risk factor 12 was<br />

found in 16.6% <strong>of</strong> 3716 patients who had information <strong>of</strong><br />

opium use in the registry.<br />

The frequencies <strong>of</strong> the atherosclerotic risk factors,<br />

demographic, and clinical characteristics <strong>of</strong> the patients<br />

≤ 35 and > 35 years old were compared. In Group I, the<br />

frequency <strong>of</strong> the male gender, current smoking, and a family<br />

history <strong>of</strong> CAD was significantly more common than that<br />

<strong>of</strong> Group II (p value < 0.001). The patients above 35 years<br />

were more likely to have diabetes mellitus (p value < 0.001),<br />

hypertension (p value < 0.001), and hyperlipidemia (p value =<br />

0.009). Although the mean total cholesterol and high density<br />

lipoprotein levels were similar between two groups, the older<br />

patients had significantly higher low density lipoprotein and<br />

FBS and lower triglyceride levels in comparison with Group<br />

I. There was no significant statistical difference in the BMI<br />

(27.7 ± 4.2 vs. 27.0 ± 4.1 in Group I vs. II, respectively; p<br />

value = 0.111) and opium use between the two groups.<br />

There were 5527 (107 from Group I and 5420 from Group<br />

II) patients with STEMI, in whom baseline hemoglobin data<br />

were available. According to the World Health Organization<br />

definition (hemoglobin < 13 g/dL and < 12 g/dL for the male<br />

and female, respectively), 15.7% <strong>of</strong> the patients (867 <strong>of</strong><br />

5420) presented with anemia. The mean hemoglobin level<br />

<strong>of</strong> Group II was lower than that <strong>of</strong> Group I (14.2 ± 1.8 vs.<br />

14.5 ± 1.5 g/dL, p value < 0.001); the young patients were<br />

less likely to be anemic compared with Group II (8.4% vs.<br />

15.8%, p value = 0.037). There were 989 (18%) patients<br />

with elevated serum creatinine (> 1.4 mg/dl). Group II<br />

patients were more likely to have impaired renal function in<br />

comparison with Group I (18.1% vs. 9.4%, p value = 0.037).<br />

There was no significant difference in the LVEF measured<br />

by echocardiography or left ventriculography between the<br />

two groups (Table 2).<br />

Significant coronary artery lesions were found in 5356<br />

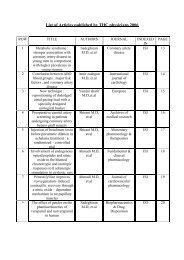

Table 1. Demographic and historical characteristics <strong>of</strong> the patients *<br />

≤ 35years (n=108) > 35 years (n=5544) p value<br />

Male gender 100 (92.6) 4412 (79.6)

Demographics and Angiographic Findings in Patients under 35 Years <strong>of</strong> ...<br />

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

Table 2. Investigation findings and treatment strategy <strong>of</strong> the patients *<br />

≤ 35 years (n=108) > 35 years (n=5544) p value<br />

Echocardiography LVEF (%) 46.3±10.4 44.5±11.5 0.134<br />

RWMA 64 (68.8) 3470 (69.2) 0.931<br />

Catheterization LVEF (%) 46.6±10.5 44.3±11.6 0.051<br />

Coronary artery dominancy<br />

Right 86 (79.6) 4627 (83.4) 0.343<br />

Left 12 (11.1) 587 (10.6)<br />

Codominant 10 (9.3) 330 (5.9)<br />

Normal coronary angiogram 20 (18.5) 116 (2.1)

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Seyed Kianoosh Hosseini et al.<br />

patients, smokers, and those with a family history <strong>of</strong> CAD<br />

have the propensity to earlier acute coronary syndromes<br />

(ACSs). 16-18 In the Sozzi et al. study, 18 the men developed<br />

AMI approximately 10 times more frequently than did the<br />

women, and also smoking and a family history were heavily<br />

present among the young patients. Zimmerman et al. 1 showed<br />

that a family history <strong>of</strong> premature CAD was more common<br />

in the young men with MI. A family history <strong>of</strong> premature<br />

MI has been considered as an independent risk factor for the<br />

development <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular events, particularly in young<br />

patients. 19-22<br />

The role <strong>of</strong> positive family history <strong>of</strong> premature CAD<br />

will be completed by many reports about the role <strong>of</strong> genetic<br />

factors in the development <strong>of</strong> atherosclerosis and occurrence<br />

<strong>of</strong> STEMI in young patients. According to recent published<br />

studies, there may be polymorphisms in genes such as<br />

methylene tetrahydr<strong>of</strong>olatereductase, 23 Platelet receptors, 24<br />

and plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI1), 25 which<br />

predispose the patients to STEMI. In contrast, there is at least<br />

one report about the polymorphism in beta fibrinogen gene<br />

and its protective effect against the incidence <strong>of</strong> premature<br />

STEMI. 26 Whether or not such findings could have therapeutic<br />

impacts needs to be illuminated in the future.<br />

As was expected, there was a lower incidence <strong>of</strong><br />

hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes in our younger<br />

17, 27,<br />

patients, which is in agreement with previous studies.<br />

28<br />

It is related to the long-term role <strong>of</strong> these metabolic and<br />

endocrine disorders in the atherosclerosis process and ACS.<br />

However, it is deserving <strong>of</strong> note that our young patients had<br />

higher levels <strong>of</strong> serum triglyceride. These findings suggest<br />

that coronary disease may have different predisposing<br />

conditions in this population. Early lifestyle modifications<br />

and pharmacological interventions should take into account<br />

smoking, dyslipidemia, and body weight control. It should<br />

be noted that hypertension and diabetes were less frequent at<br />

the young age. A general notion has evolved that the intensity<br />

<strong>of</strong> preventive efforts should be adjusted to a patient’s risk for<br />

developing CAD.<br />

Our findings that a normal coronary angiogram was more<br />

frequent in the young patients and that they had a higher<br />

frequency <strong>of</strong> single-vessel disease as compared to the older<br />

patients are consistent with previous reports. 1, 3, 29 Our older<br />

patients were more commonly diagnosed as multi-vessel<br />

disease in the coronary angiogram. It seems that younger<br />

patients who present with STEMI have lower atherosclerotic<br />

burden but higher propensity to thrombus formation.<br />

Autopsy observations have shown that the occurrence <strong>of</strong><br />

MI in young people with cardiovascular risk factors could<br />

be the expression <strong>of</strong> a premature and severe atherosclerotic<br />

process. 30 Not surprisingly, we observed that the young<br />

patients were less likely to have prior catheterization and<br />

to refer for CABG as their treatment strategy for coronary<br />

revascularization.<br />

The current analysis is strengthened by the diversity and<br />

size <strong>of</strong> the population studied; be that as it may, a number<br />

<strong>of</strong> limitations should be noted. Patients ≤ 35 years <strong>of</strong> age<br />

comprised just 1.9% <strong>of</strong> the total STEMI population in the<br />

angiography registry, but this analysis <strong>of</strong> 5652 patients <strong>of</strong><br />

STEMI represents one <strong>of</strong> the largest studies to focus on<br />

patients after infarction. As this study population represented<br />

relatively high-risk patients with MI, we remain cautious<br />

in generalizing these results to a broader group <strong>of</strong> lowerrisk,<br />

post-MI patients. Furthermore, our patients had<br />

been followed prospectively through other registries (i.e.<br />

Angioplasty and CABG); nevertheless, the present study,<br />

being a single-center survey may have lost some data <strong>of</strong> the<br />

patients who were not admitted. Some long-term follow-up<br />

events, particularly death and stroke, were not determined in<br />

this study. Accordingly, the present analysis cannot claim to<br />

represent the findings for all patients early after MI.<br />

Conclusion<br />

In conclusion, we found that the male gender,<br />

smoking, family history <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular diseases, and<br />

hypertriglyceridemia were more prevalent in the STEMI<br />

patients ≤ 35 years, whereas the elderly patients were more<br />

likely to have dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes.<br />

Medical treatment or PCI were the preferred therapeutic<br />

strategy recommended to the younger patients in contrast<br />

to their older counterparts, in whom CABG was more<br />

commonly recommended. Further studies about the impact<br />

<strong>of</strong> genetic factors in the development <strong>of</strong> STEMI in young<br />

patients are needed.<br />

Acknowledgment<br />

We extend our gratitude to Dr. Mahmood Sheikhfathollahi<br />

for his assistance in the statistical analysis. This study was<br />

approved and supported by <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical<br />

Sciences.<br />

References<br />

1. Zimmerman FH, Cameron A, Fisher LD, Ng G. Myocardial<br />

infarction in young adults: angiographic characterisation, risk<br />

factors and prognosis (Coronary Artery Surgery Study Registry).<br />

J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26:654-661.<br />

2. Colkesen AY, Acil T, Demircan S, Sezgin AT, Muderrisoglu H.<br />

Coronary lesion type, location, and characteristics <strong>of</strong> acute ST<br />

elevation myocardial infarction in young adults under 35 years <strong>of</strong><br />

age. Coron Artery Dis 2008;19:345-347.<br />

3. Pineda J, Marín F, Roldán V, Valencia J, Marco P, Sogorb F.<br />

Premature myocardial infarction: clinical pr<strong>of</strong>ile and angiographic<br />

findings. Int J Cardiol 2008;126:127-129.<br />

4. Ghadimi H, Bishehsari F, Allameh F. Clinical characteristics,<br />

hospital morbidity and mortality, and up to 1-year follow-up events<br />

<strong>of</strong> acute myocardial infarction patients: the first report from Iran.<br />

66

Demographics and Angiographic Findings in Patients under 35 Years <strong>of</strong> ...<br />

Coron Artery Dis 2006;17:585-591.<br />

5. Morillas P, Bertomeu V, Pabon P. Characteristics and outcome <strong>of</strong><br />

acute myocardial infarction in young patients: the PRIAMHO II<br />

study. Cardiology 2007;107:217-25.<br />

6. Alizadehasl A, Sepasi F, Toufan M. Risk factors, clinical<br />

manifestations and outcome <strong>of</strong> acute myocardial infarction in<br />

young patients. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res 2010;2:29-34.<br />

7. Choudhury L, Marsh JD. Myocardial infarction in young patients.<br />

Am J Med 1999;107:254-261.<br />

8. Hosseini SK, Soleimani A, Karimi AA, Sadeghian S, Darabian S,<br />

Abbasi SH, Ahmadi SH, Zoroufian A, Mahmoodian M, Abbasi<br />

A. Clinical features, management and in-hospital outcome <strong>of</strong> ST<br />

elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in young adults under 40<br />

years <strong>of</strong> age. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2009;72:71-76.<br />

9. Celik T, Iyisoy A. Premature coronary artery disease in young<br />

patients: an uncommon but growing entity. Int J Cardiol<br />

2010;144:131-132.<br />

10. Gaeta G, Cuomo S, Capozzi G, Foglia MC, Barra S, Madrid A,<br />

Stornaiuolo V, Trevisan M. Lipoprotein (a) levels are increased<br />

in healthy young subjects with parental history <strong>of</strong> premature<br />

myocardial infarction. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2008;18:492-<br />

496.<br />

11. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, Jr, King SB, 3rd, Anderson JL,<br />

Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE,<br />

Jr, Green LA, Hochman JS, Jacobs AK, Krumholz HM, Morrison<br />

DA, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Peterson ED, Sloan MA, Whitlow PL,<br />

Williams DO. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the<br />

management <strong>of</strong> patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction<br />

(updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/<br />

AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention<br />

(updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report <strong>of</strong><br />

the American College <strong>of</strong> Cardiology Foundation/American <strong>Heart</strong><br />

Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol<br />

2009;54:2205-2241.<br />

12. Sadeghian S, Darvish S, Davoodi G, Salarifar M, Mahmoodian<br />

M, Fallah N, Karimi AA. The association <strong>of</strong> opium with coronary<br />

artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:715-717.<br />

13. Caro JJ, Migliaccio-Walle K. Generalizing the results <strong>of</strong> clinical<br />

trials to actual practice: the example <strong>of</strong> clopidogrel therapy for the<br />

prevention <strong>of</strong> vascular events. CAPRA (CAPRIE Actual Practice<br />

Rates Analysis) Study Group. Clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients<br />

at risk <strong>of</strong> ischaemic events. Am J Med 1999;107:568-572.<br />

14. Yusuf S, Flather M, Pogue J, Hunt D, Varigos J, Piegas L, Avezum<br />

A, Anderson J, Keltai M, Budaj A, Fox K, Ceremuzynski L.<br />

Variations between countries in invasive cardiac procedures and<br />

outcomes in patients with suspected unstable angina or myocardial<br />

infarction without initial ST elevation. OASIS (Organisation to<br />

assess strategies for ischaemic syndromes) registry investigators.<br />

Lancet 1998;352:507-514.<br />

15. Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, Arveiler D,<br />

Rajakangas AM, Pajak A. Myocardial infarction and coronary<br />

deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project.<br />

Registration procedures, event rates and case-fatality rates in<br />

38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation<br />

1994;90:583-612.<br />

16. Dolder MA, Oliver MF. Myocardial infarction in young men. Br<br />

<strong>Heart</strong> J 1975;37:493-503.<br />

17. Holt BD, Gilpin EA, Henning H. Myocardial infarction in young<br />

patients: an analysis by age subsets. Circulation 1986;74:7127-<br />

7121.<br />

18. Sozzi FB, Danzi GB, Foco L, Ferlini M, Tubaro M, Galli M, Celli<br />

P, Mannucci PM. Myocardial infarction in the young: a sex-based<br />

comparison. Coron Artery Dis 2007;18:429-431.<br />

19. Andresdottir MB, Sigurdsson G, Sigvaldason H, Gudnason V;<br />

Reykjavik Cohort Study. Fifteen percent <strong>of</strong> myocardial infarctions<br />

and coronary revascularizations explained by family history<br />

unrelated to conventional risk factors. The Reykjavik Cohort<br />

Study. Eur <strong>Heart</strong> J 2002;23:1655-1663.<br />

20. Sesso HD, Lee IM, Gaziano JM. Maternal and paternal history <strong>of</strong><br />

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

myocardial infarction and risk <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular disease in men<br />

and women. Circulation 2001;104:393-398.<br />

21. Philips B, de Lemos JA, Patel MJ. Relation <strong>of</strong> family history <strong>of</strong><br />

myocardial infarction and the presence <strong>of</strong> coronary arterial calcium<br />

in various age and risk-factor groups. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:825-<br />

829.<br />

22. Hoseini K, Sadeghian S, Mahmoudian M, Hamidian R, Abbasi<br />

A. Family history <strong>of</strong> cardiovascular disease as a risk factor for<br />

coronary artery disease in adult <strong>of</strong>fspring. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis<br />

2008;70:84-87.<br />

23. Isordia-Salas I, Trejo-Aguilar A, Valadés-Mejía MG, Santiago-<br />

Germán D, Leaños-Miranda A, Mendoza-Valdéz L, Jáuregui-<br />

Aguilar R, Borrayo-Sánchez G, Majluf-Cruz A. C677T<br />

polymorphism <strong>of</strong> the 5,10 MTHFR gene in young Mexican<br />

subjects with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Arch Med Res<br />

2010;41:246-250.<br />

24. Motovska Z, Kvasnicka J, Widimsky P, Petr R, Hajkova J,<br />

Bobcikova P, Osmancik P, Odvodyova D, Katina S. Platelet<br />

glycoprotein GP VI 13254C allele is an independent risk factor <strong>of</strong><br />

premature myocardial infarction. Thromb Res 2010;125:e61-64.<br />

25. Isordia-Salas I, Leaños-Miranda A, Sainz IM, Reyes-Maldonado<br />

E, Borrayo-Sánchez G. Association <strong>of</strong> the plasminogen activator<br />

inhibitor-1 gene 4G/5G polymorphism with ST elevation acute<br />

myocardial infarction in young patients. Rev Esp Cardiol<br />

2009;62:365-372.<br />

26. Rallidis LS, Gialeraki A, Fountoulaki K, Politou M, Sourides V,<br />

Travlou A, Lekakis I, Kremastinos DT. G-455A polymorphism<br />

<strong>of</strong> beta-fibrinogen gene and the risk <strong>of</strong> premature myocardial<br />

infarction in Greece. Thromb Res 2010;125:34-37.<br />

27. Garoufalis S, Kouvaras G, Vitsias G, Perdikouris K, Markatou<br />

P, Hatzisavas J, Kassinos N, Karidis K, Foussas S. Comparison<br />

<strong>of</strong> angiographic findings, risk factors, and long term followup<br />

between young and old patients with a history <strong>of</strong> myocardial<br />

infarction. Int J Cardiol 1998;67:75-80.<br />

28. Cole JH, Miller JI, 3rd, Sperling LS, Weintraub WS. Long-term<br />

follow-up <strong>of</strong> coronary artery disease presenting in young adults. J<br />

Am Coll Cardiol 2003;4:521-528.<br />

29. Fullhaas J, Rickenbacher P, Pfisterer M. Long-term prognosis <strong>of</strong><br />

young patients after myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era.<br />

Clin Cardiol 1997;20:993-998.<br />

30. Genest JJ, McNamara JR, Salem DN, Schaefer EJ. Prevalence <strong>of</strong><br />

risk factors in men with premature coronary artery disease. Am J<br />

Cardiol 1991;67:1185-1189.<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>67

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Original Article<br />

Signal-Averaged Electrocardiography in Patients with<br />

Advanced <strong>Heart</strong> Failure: A Better Indicator <strong>of</strong> Left<br />

Ventricular Enlargement Compared with Conventional<br />

Electrocardiography<br />

Mohammad Alasti, MD 1* , Majid Haghjoo, MD 2 , Abolfath Alizadeh, MD 2 ,<br />

Mohammad Hossein Nikoo, MD 3 , Hamid Reza Bonakdar, MD4, Bita Omidvar,<br />

MD 5<br />

1<br />

Imam Khomeini Hospital, Jundishapur <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.<br />

2<br />

Rajaie Cardiovascular Medical and Research <strong>Center</strong>, <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, <strong>Tehran</strong>, Iran.<br />

3<br />

Kosar Hospital, Shiraz, Iran.<br />

4<br />

Heshmat Hospital, Gilan <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.<br />

5<br />

Golestan Hospital, Jundishapur <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.<br />

Abstract<br />

Received 11 August 2010; Accepted 12 January 2011<br />

Background: The signal-averaged electrocardiography is a noninvasive method to evaluate the presence <strong>of</strong> the potentials<br />

generated by tissues activated later than their usual timing in the cardiac cycle. The purpose <strong>of</strong> this study was to demonstrate<br />

the correlation between the filtered QRS duration obtained via the signal-averaged electrocardiography and left ventricular<br />

dimensions and volumes and then to compare it with the standard electrocardiography.<br />

Methods: We included patients with advanced systolic left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction ≤ 35%). All the patients<br />

underwent surface twelve-lead electrocardiography, signal-averaged electrocardiography, and echocardiography.<br />

Results: The study included 86 patients with a mean age <strong>of</strong> 54.66 ± 13.23 years. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction<br />

was 18.31 ± 5.49%; the mean QRS duration was 0.14 ± 0.02 sec; and 52% <strong>of</strong> the patients had left bundle branch block. The<br />

mean filtered QRS duration was 145.87 ± 24.89 ms. Our data showed a significant linear relation between the filtered QRS<br />

duration and left ventricular end-systolic volume, left ventricular end-diastolic volume, left ventricular end-systolic diameter,<br />

and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; the correlation coefficient was, however, not good. There was no significant<br />

correlation between the QRS duration and left ventricular diameters and volumes.<br />

Conclusion: The filtered QRS duration has a better correlation with left ventricular dimensions and volumes than does the<br />

QRS duration in the standard electrocardiography.<br />

J Teh Univ <strong>Heart</strong> Ctr 2011;6(2):68-71<br />

This paper should be cited as: Alasti M, Haghjoo M, Alizadeh A, Nikoo MH, Bonakdar HR, Omidvar B. Signal-Averaged Electrocardiography<br />

in Patients with Advanced <strong>Heart</strong> Failure: A Better Indicator <strong>of</strong> Left Ventricular Enlargement Compared with Conventional Electrocardiography.<br />

J Teh Univ <strong>Heart</strong> Ctr 2011;6(2):68-71.<br />

Keywords: <strong>Heart</strong> failure • Echocardiography • Electrocardiography • <strong>Heart</strong> ventricles<br />

*<br />

Corresponding Author: Mohammad Alasti, Assistant Pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> Cardiology, Jondishpour <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical Sciences, Imam Khomeini Hospital,<br />

Azadegan Avenue, Ahwaz, Iran. 6193673166. Tel: +98 611 4457205. Fax: +98 611 4457205. E-mail: alastip@gmail.com.<br />

68

Signal-Averaged Electrocardiography in Patients with Advanced <strong>Heart</strong> Failure: ...<br />

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

Introduction<br />

The high resolution electrocardiography (ECG) is<br />

designed for the body surface recording <strong>of</strong> the cardiac signals<br />

that are not visible on the standard ECG. Signal averaging is<br />

an approach to produce a high resolution electrocardiogram.<br />

In this type <strong>of</strong> electrocardiography, late potentials are<br />

generated by tissues activated later than their usual timing in<br />

the cardiac cycle. 1 We, therefore, designed an observational<br />

study aimed at evaluating the possible correlation between<br />

the data obtained by the signal-averaged electrocardiography<br />

(SAECG) and left ventricular (LV) dimensions and volumes<br />

and compare it with the standard ECG.<br />

Methods<br />

The patients included in the study were selected<br />

consecutively among those referred with a diagnosis <strong>of</strong><br />

heart failure. The inclusion criteria were advanced systolic<br />

LV dysfunction (LV ejection fraction [LVEF] ≤ 35%) and<br />

underlying cause (idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy or<br />

ischemic heart disease). All the patients signed written<br />

informed consent. We excluded patients with non-sinus<br />

rhythm, previous pacemaker implantation, a recent myocardial<br />

infarction (< 3 months), and severe aortic disease. All the<br />

patients underwent standard twelve-lead ECG, SAECG, and<br />

two-dimensional echocardiography.<br />

Imaging was done in the left lateral decubitus position,<br />

recording the parasternal and apical views (standard longaxis<br />

and two- and four-chamber images) with the aid <strong>of</strong> a<br />

commercially available system (Vingmed 7, General Electric,<br />

Milwaukee, WI, USA). A 3.5-MHz transducer was used.<br />

The LV volumes (end-systolic and end-diastolic) and LVEF<br />

were calculated from the conventional apical two- and fourchamber<br />

images utilizing the biplane Simpson technique.<br />

The QRS duration was measured on the surface ECG. The<br />

ECG was recorded at a speed <strong>of</strong> 25 mm/sec and a scale <strong>of</strong><br />

10 mm/mV. The QRS duration was measured as the widest<br />

QRS complex in the precordial leads. QRS durations ≥ 0.12<br />

sec; no q-wave but slurred, broad R waves in leads I, aVL,<br />

and V 6<br />

; and rS or QS deflections in lead V 1<br />

were considered<br />

as the ECG features <strong>of</strong> left bundle branch block (LBBB). On<br />

the other hand, QRS durations ≥ 120 ms, broad and notched<br />

R waves in leads V 1<br />

and V 2<br />

, and deep S deflections in the<br />

left precordial leads and I were noted as the ECG features<br />

<strong>of</strong> right bundle branch block (RBBB). A prolonged QRS<br />

not associated with the typical features <strong>of</strong> bundle branch<br />

block was labeled as nonspecific intraventricular conduction<br />

delay.<br />

Filtered QRS durations (fQRS) were calculated using the<br />

SAECG (Hellige EK 56, Marquette, Freiburg, Germany)<br />

with noise level < 0.3 µV and high-pass filtering <strong>of</strong> 35 Hz.<br />

The key hardware elements <strong>of</strong> the system were an amplifier,<br />

a convertor for the digitalization <strong>of</strong> the signals, a signal<br />

processor, and a printer. In this system, a computer algorithm<br />

was utilized to identify the QRS onset and <strong>of</strong>fset. Filtering<br />

was applied to reduce the residual noise and improve the<br />

identification <strong>of</strong> the low potentials.<br />

The continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard<br />

deviation values. Linear regression analysis was the chosen<br />

method for evaluating the association between the signalaveraged<br />

data and the echocardiographic indices. A p value<br />

< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.<br />

Results<br />

The study population consisted <strong>of</strong> 86 patients: 67 (77.9%)<br />

men and 19 (22.1%) women with a mean age <strong>of</strong> 54.66 ± 13.23<br />

years (range: 18-79). The underlying etiology <strong>of</strong> heart failure<br />

was ischemic in 60% <strong>of</strong> the patients. Seventy-two (83.8%)<br />

patients were in New York <strong>Heart</strong> Association (NYHA) class<br />

III. The baseline characteristics <strong>of</strong> the study population are<br />

summarized in Table 1.<br />

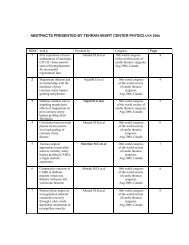

Table 1. Baseline characteristics <strong>of</strong> study population *<br />

Variable n=86<br />

Age (y) 54.66±13.23<br />

Male/Female 67 (77.9) / 19 (22.1)<br />

Etiology <strong>of</strong> heart failure<br />

Ischemic 52 (60)<br />

Idiopathic 34 (40)<br />

NYHA class<br />

NYHA class II 12 (14)<br />

NYHA class III 72 (83.8)<br />

NYHA class IV 2 (2.3)<br />

QRS morphology<br />

Left bundle branch block 45 (52)<br />

Right bundle branch block 6 (7)<br />

Nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay 35 (41)<br />

*<br />

Data are presented as mean±SD or n (%)<br />

All the patients had sinus rhythm on the ECG. The mean<br />

QRS duration was 0.14 ± 0.03 sec (range: 0.08-0.2 sec), and<br />

45 (52%) patients had LBBB morphology. The mean fQRS<br />

duration was 145.87 ± 24.89 ms (range: 86-200 ms).<br />

The mean LVEF was 18.31 ± 5.49% (range: 10-33%),<br />

and 15.3% <strong>of</strong> the patients had severe mitral regurgitation.<br />

Detailed echocardiographic characteristics <strong>of</strong> the patients are<br />

presented in Table 2.<br />

The multiple linear regression (stepwise method)<br />

demonstrated that while there was a significant correlation<br />

between the fQRS duration and LV end-systolic volume<br />

(r = 0.37, p value = 0.000) (Figure 1-A), LV end-systolic<br />

diameter (r = 0.24, p value = 0.031) (Figure 1-B), LV end-<br />

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong>69

The <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tehran</strong> <strong>University</strong> <strong>Heart</strong> <strong>Center</strong><br />

Mohammad Alasti et al.<br />

Figure 1. A-Correlation between the left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV, ml) and filtered QRS duration (fQRS, ms) (r = 0.37, p value = 0.000).<br />

B- Correlation between the left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD, cm) and filtered QRS duration (fQRS, ms) (r = 0.24, p value = 0.031).<br />

C- Correlation between the left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV, ml) and filtered QRS duration (fQRS, ms) (r = 0.31, p value = 0.004).<br />

D- Correlation between left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD, cm) and filtered QRS duration (fQRS, ms) (r = 0.23, p value = 0.039)<br />

diastolic volume (r = 0.31, p value = 0.004) (Figure 1-C), and<br />

LV end-diastolic diameter (r = 0.23, p value = 0.039) (Figure<br />

1-D), there was no significant correlation between the fQRS<br />

duration and LVEF. In addition, the relation between age,<br />

sex, and underlying disease and the parameters in the model<br />

was not significant.<br />

There was no statistically significant relation between the<br />

QRS duration and LV dimensions, volumes, and EF (Table 3).<br />

Discussion<br />

QRS prolongation ( > 120 ms) occurs in 14% to 47%<br />

<strong>of</strong> patients with heart failure and is a common finding in<br />

approximately 30%. LBBB occurs more commonly than<br />

does RBBB (25% to 36% vs. 4% to 6%). 2 The prolongation <strong>of</strong><br />

Table 2. Echocardiographic characteristics <strong>of</strong> study population (n=86) *<br />

Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) 18.31±5.49 (10-33)<br />

Left ventricular end-systolic diameter (cm) 6.15±0.90 (4.1-8.9)<br />

Left ventricular end-systolic volume (ml) 163.76±58.34 (53-367)<br />

Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (cm) 7.00±0.86 (5.1-9.4)<br />

Left ventricular end-diastolic volume (ml) 209.56±64.16 (72-430)<br />

*<br />

Data are presented as mean±SD (range)<br />

70

Signal-Averaged Electrocardiography in Patients with Advanced <strong>Heart</strong> Failure: ...<br />

TEHRAN HEART CENTER<br />

Table 3. Correlation <strong>of</strong> QRS duration and left ventricular dimensions and volumes assessed by two-dimensional echocardiography<br />

Variable Correlation Coefficient P value<br />

Left ventricular end-systolic diameter 0.13 0.249<br />

Left ventricular end-systolic volume 0.17 0.113<br />

Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter 0.10 0.358<br />

Left ventricular end-diastolic volume 0.11 0.329<br />

Left ventricular ejection fraction 0.04 0.125<br />

QRS is a significant predictor for LV systolic dysfunction in<br />

patients with heart failure. One heart failure study indicated<br />

that the incidence <strong>of</strong> QRS prolongation increased from<br />

10% to 32% and 53% when patients moved from NYHA<br />

functional class I to class II and III, respectively. 2<br />

In patients with heart failure, an inverse correlation<br />

exists between QRS prolongation and LVEF. In a study, a<br />

stepwise increase was found in the prevalence <strong>of</strong> systolic<br />

LV dysfunction as the QRS complex duration increased<br />

progressively above 120 ms. 2 As was stated in previous<br />

studies, the baseline QRS duration has no correlation with<br />

intraventricular dyssynchrony and is not predictive for<br />

clinical and echocardiographic responses. 2, 3<br />

The SAECG is a noninvasive test for the risk stratification<br />

<strong>of</strong> sudden cardiac deaths, especially in the survivors<br />

<strong>of</strong> myocardial infarction. This technique results in the<br />

improvement <strong>of</strong> the signal-to-noise ratio, thus allowing<br />

analysis <strong>of</strong> signals that are too small to be detected by routine<br />

measurement. 4<br />

There are some studies showing a better correlation<br />

between the SAECG data and intraventricular<br />

dyssynchrony. 5, 6 Our data showed that the fQRS duration<br />

in the SAECG had a significant linear correlation with LV<br />

diameters and volumes (despite low correlation coefficients)<br />

and was a better indicator <strong>of</strong> LV enlargement than was the<br />

QRS duration in the standard twelve-lead ECG. Hence,<br />

the SAECG can be more informative than standard ECG<br />

in patients with heart failure and may be used more in the<br />

future.<br />

This study has some major limitations, first and foremost<br />

amongst which is its small size, which requires the evaluation<br />

<strong>of</strong> a larger group <strong>of</strong> patients to confirm its results. Another<br />

limitation is the heterogeneity <strong>of</strong> the study population<br />

ins<strong>of</strong>ar as patients with ischemic or idiopathic dilated<br />

cardiomyopathies and patients with intraventricular delay or<br />

narrow QRS were all included in this study. In addition, the<br />

fact that the study patients were selected from those referred<br />

to us certainly creates some selection bias.<br />

our findings warrants further investigation.<br />

Acknowledgment<br />

This study was supported by Cardiovascular Research<br />

<strong>Center</strong> <strong>of</strong> Ahvaz Jundishapur <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Medical<br />

Sciences.<br />

References<br />

1. Berbari EJ. High resolution electrocardiography. In: Zipes DP,<br />

Jalife J. eds. Cardiac Electrophysiology: from Cell to Bedside. 5th<br />

ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004. p. 793-802.<br />

2. Kashani A, Barold S. Significance <strong>of</strong> QRS complex duration in<br />

patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:2183-2192.<br />

3. Mollema SA, Bleeker GB, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ, Bax<br />

JJ. Usefulness <strong>of</strong> QRS duration to predict response to cardiac<br />