Left Further Behind - Child Poverty Action Group

Left Further Behind - Child Poverty Action Group

Left Further Behind - Child Poverty Action Group

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

under the Māori Health Strategy suggests that Whānau Ora, in its application to social services,<br />

is likely to provide real and substantive Māori decision-making and engagement in social policy<br />

making as well as Māori design and implementation of social initiatives within communities (Ministry<br />

of Health, 2002 , p.iii). However, as suggested by the experiences in health and in existing familycentred<br />

programmes, it may take at least a few years for such changes to result in measurable<br />

lessening in the inequities that create poverty within Māori whānau and communities.<br />

Given the high likelihood that the Whānau Ora approach will struggle to make an impact on the<br />

implementation of the social security system, and the considerable time needed for increased Māori<br />

decision-making and engagement in social policy to result in measurable change in poverty rates for<br />

whānau Māori, poverty, for many Māori children, will remain the daily reality in the short to medium<br />

term.<br />

Māori and <strong>Poverty</strong><br />

There is no need to replicate the enormous amount of data which show clearly the economically<br />

disadvantaged position of Māori. In fact, the Whānau Ora Taskforce Report (Whānau Ora Taskforce,<br />

2010, p. 15) summarises this:<br />

Despite limitations, current data suggest that whānau members face a disproportionate level of<br />

risk for adverse outcomes, as seen in lower standards of health, poorer educational outcomes,<br />

marginalisation within society, intergenerational unemployment and increased rates of offending.<br />

<strong>Further</strong>, in response to socio-economic hardship, a range of problems are likely to co-exist<br />

within the same household, affecting health, employment, behaviour, education, and lifestyle<br />

simultaneously. In addition to socio-economic determinants, some studies have shown that even<br />

when social and economic circumstances are taken into account, Māori individuals still fare worse<br />

than non-Māori.<br />

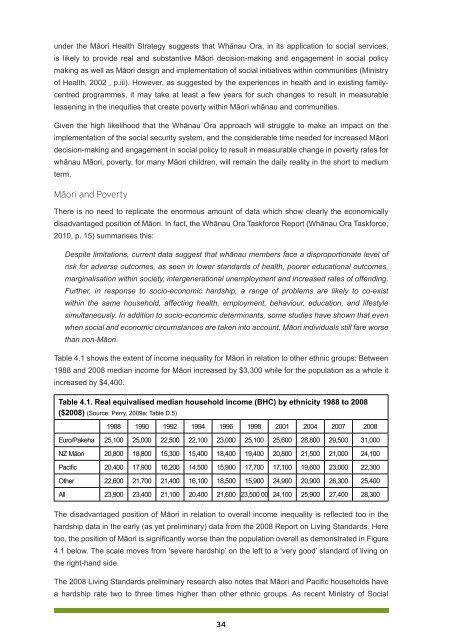

Table 4.1 shows the extent of income inequality for Māori in relation to other ethnic groups: Between<br />

1988 and 2008 median income for Māori increased by $3,300 while for the population as a whole it<br />

increased by $4,400.<br />

Table 4.1. Real equivalised median household income (BHC) by ethnicity 1988 to 2008<br />

($2008) (Source: Perry, 2009a: Table D.5)<br />

1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2001 2004 2007 2008<br />

Euro/Pakeha 25,100 25,000 22,500 22,100 23,000 25,100 25,600 28,800 29,500 31,000<br />

NZ Māori 20,800 18,800 15,300 15,400 18,400 19,400 20,800 21,500 21,000 24,100<br />

Pacific 20,400 17,900 16,200 14,500 15,900 17,700 17,100 19,600 23,000 22,300<br />

Other 22,600 21,700 21,400 16,100 18,500 15,900 24,900 20,900 26,300 25,400<br />

All 23,900 23,400 21,100 20,400 21,600 23,500 00 24,100 25,900 27,400 28,300<br />

The disadvantaged position of Māori in relation to overall income inequality is reflected too in the<br />

hardship data in the early (as yet preliminary) data from the 2008 Report on Living Standards. Here<br />

too, the position of Māori is significantly worse than the population overall as demonstrated in Figure<br />

4.1 below. The scale moves from ‘severe hardship’ on the left to a ‘very good’ standard of living on<br />

the right-hand side.<br />

The 2008 Living Standards preliminary research also notes that Māori and Pacific households have<br />

a hardship rate two to three times higher than other ethnic groups. As recent Ministry of Social<br />

34