Left Further Behind - Child Poverty Action Group

Left Further Behind - Child Poverty Action Group

Left Further Behind - Child Poverty Action Group

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Pacific families in New Zealand<br />

Low household incomes and the marked inequality between Pacific incomes and other New<br />

Zealanders shape health, educational and social outcomes for our families. Pacific median household<br />

income is lower than non-Pacific people (Ministry of Social Development, 2007, 2010b). However the<br />

additional financial commitments of Church, and remittances to extended family back home in the<br />

Islands, result in Pacific families having even less money available for themselves (Tumama Cowley,<br />

Paterson, & Williams, 2004). Essentials such as healthcare for children may take second place to the<br />

other priorities of rent and cultural commitments. Pefi Kingi (2008) writes of Pacific families:<br />

..the family is the cornerstone of personal life from birth to death, and identity can centre on one’s<br />

roles, duties and responsibilities within the family… it maybe that collective well-being is awarded<br />

a higher priority than that of the individual, particularly if that individual is a sick child. (Craig,<br />

Taufa, Jackson, & Han, 2008, p. 12)<br />

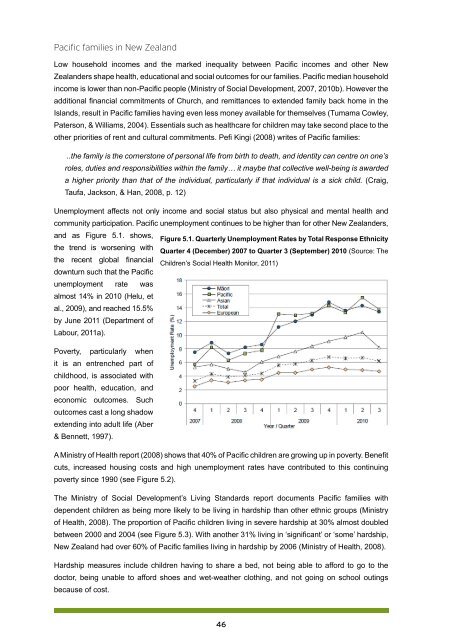

Unemployment affects not only income and social status but also physical and mental health and<br />

community participation. Pacific unemployment continues to be higher than for other New Zealanders,<br />

and as Figure 5.1. shows,<br />

Figure 5.1. Quarterly Unemployment Rates by Total Response Ethnicity<br />

the trend is worsening with<br />

Quarter 4 (December) 2007 to Quarter 3 (September) 2010 (Source: The<br />

the recent global financial<br />

<strong>Child</strong>ren’s Social Health Monitor, 2011)<br />

downturn such that the Pacific<br />

unemployment rate was<br />

almost 14% in 2010 (Helu, et<br />

al., 2009), and reached 15.5%<br />

by June 2011 (Department of<br />

Labour, 2011a).<br />

<strong>Poverty</strong>, particularly when<br />

it is an entrenched part of<br />

childhood, is associated with<br />

poor health, education, and<br />

economic outcomes. Such<br />

outcomes cast a long shadow<br />

extending into adult life (Aber<br />

& Bennett, 1997).<br />

A Ministry of Health report (2008) shows that 40% of Pacific children are growing up in poverty. Benefit<br />

cuts, increased housing costs and high unemployment rates have contributed to this continuing<br />

poverty since 1990 (see Figure 5.2).<br />

The Ministry of Social Development’s Living Standards report documents Pacific families with<br />

dependent children as being more likely to be living in hardship than other ethnic groups (Ministry<br />

of Health, 2008). The proportion of Pacific children living in severe hardship at 30% almost doubled<br />

between 2000 and 2004 (see Figure 5.3). With another 31% living in ‘significant’ or ‘some’ hardship,<br />

New Zealand had over 60% of Pacific families living in hardship by 2006 (Ministry of Health, 2008).<br />

Hardship measures include children having to share a bed, not being able to afford to go to the<br />

doctor, being unable to afford shoes and wet-weather clothing, and not going on school outings<br />

because of cost.<br />

46