You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

A Half-American<br />

Writer<br />

in case he should ever need to use them. “Smooth as surah”<br />

he wrote years later in Visions of Gerard, describing the skin<br />

of a character named Mr. Groscorp.<br />

In Lowell, Jack had begun his education at the<br />

neighborhood parochial school, St. Louis de France.<br />

There the morning classes were taught in French and the<br />

afternoon classes were taught in English. The students<br />

pledged allegiance to la race Canadienne as well as the<br />

American flag. The huge redbrick mills along the<br />

Merrimack River pointed to the fate that awaited many<br />

of Jack’s classmates and that Jack would become determined<br />

to escape. Very few young Franco Americans in Jack’s day<br />

left the communities they had been raised in or succeeded in<br />

going to college; very few attempted the kind of lonely<br />

journey Jack would take into the American mainstream. (“I<br />

don’t even look like a<br />

writer,” Jack would later<br />

confess to his journal. “I<br />

look like a lumberjack.”)<br />

There was still tremendous<br />

prejudice against Jack’s<br />

people, with most<br />

Americans believing they<br />

were backward. Up where<br />

Jack came from they were<br />

called “white niggers” of<br />

“the Chinese of New<br />

England.” “Dumb<br />

Canuck” was a common epithet that I even heard used<br />

teasingly by one of Jack’s friends. But even in the 1950’s,<br />

Franco Americans still kept to themselves for other reasons:<br />

the almost mystical belief that they must uphold the old<br />

ideals and customs of what they called la survivance and<br />

continue to speak their distinctive language, which was so<br />

woven into their religion.<br />

Lowell, the birthplace of the American industrial<br />

revolution, was a melting pot, where people from various<br />

ethnic groups—Irish Catholic, Greek, Syrian, as well as a<br />

sprinkling of Jews—had come in the last decades of the 19 th<br />

century to make their living in the mills, and where the<br />

French Canadians, escaping from starvation on their<br />

hardscrabble potato farms in Quebec, had been willing to<br />

take the worst jobs. People from these different groups<br />

mingled in the mills and the bustling downtown streets and<br />

went home to their separate neighborhoods; their children<br />

met each other in Lowell’s public schools and on the<br />

baseball fields. There were handsome pubic buildings in<br />

Lowell, such as the Public Library and the Atheneum that<br />

had been built by wealthy New England mill owners; there<br />

were also neighborhoods of wooden tenements where there<br />

were frequent fires and epidemics of cholera and meningitis<br />

and where many of the workers in the textile mills, where<br />

the windows were nailed shut, suffered from emphysema<br />

and tuberculosis. The deaths of children were not at all<br />

uncommon in Lowell. Jack’s mother had grown up in the<br />

nearby town of Nashua and gone to work in a shoe factory<br />

at the age of fifteen; she could write English quite fluently<br />

but never learned to speak it well. Jack’s. Father, Leo<br />

Kerouac, was bright and enterprising, and his command of<br />

English was unusually good. He was a reader, who believed<br />

that nothing compared to French culture, and worshipped<br />

Balzac and Victor Hugo. Until he lost it during<br />

the Depression, when the Kerouac’s became poor, Leo had<br />

his own small printing business, which did not confine itself<br />

to the Franco American community. Compared to most<br />

French kids, Jack’s early years were relatively privileged,<br />

although they were<br />

darkened by the death of<br />

his nine-year-old brother<br />

Gerard—a traumatic event<br />

that haunted Jack his entire<br />

life...<br />

Jack picked up his<br />

first words in English from<br />

the only Irish Catholic boy<br />

in his French-speaking<br />

kindergarten. He learned<br />

more from the half days of<br />

instruction in his parish<br />

school, St. Louis de France, but he undoubtedly would<br />

have continued his French education through high school,<br />

if the rezoning of his French Catholic middle school had not<br />

forced him to transfer to Bartlett Junior High School in<br />

Seventh Grade. If this had not happened, his grasp of<br />

English might have remained uncertain and handicapped<br />

his writing. His parents registered him at Bartlett as a<br />

commercial student.<br />

Embarrassed by his accent, one of the contributing factors<br />

to his lifelong shyness, he rarely spoke in his classes.<br />

Fortunately a discerning English teacher noticed how<br />

surprisingly well Jackie Kerouac could write. She advised<br />

him to start going to the Public Library and recommended<br />

that he read Longfellow and Twain. Every Saturday he took<br />

home an armload of books. He was a book-hungry kid,<br />

who read indiscriminately and ravenously—everything from<br />

The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come to the novels of<br />

Jack London, Charles Dickens and Arthur Conan Doyle. At<br />

sixteen, when he was cutting school to spend days at the<br />

library, he would discover Goethe, who had a lasting<br />

influence on his thinking. He was also addicted to pulp<br />

fiction, absorbing the American vernacular from The Shadow<br />

series, as well as from comics, sports novels and westerns.<br />

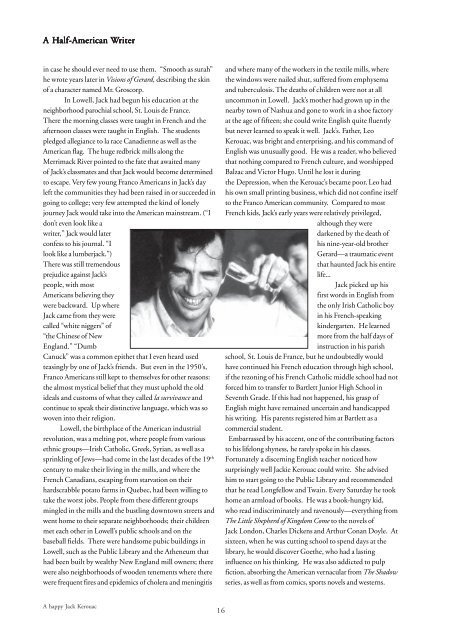

A happy Jack Kerouac<br />

16