Ron Carter Esperanza Spalding - Downbeat

Ron Carter Esperanza Spalding - Downbeat

Ron Carter Esperanza Spalding - Downbeat

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

RON CARTER<br />

ferent concepts, 16 different events. My feature is to be playing every<br />

chorus of every song. It’s about my desire to let the soloists play something<br />

different every night, making the backgrounds feel different by<br />

my notes and rhythms. I’d much rather be known as the bass player who<br />

made the band sound great, but different, every night.”<br />

In a DownBeat Blindfold Test a few years ago, bassist Stanley Clarke<br />

commented on <strong>Carter</strong>’s duo performance of “Stardust” with pianist<br />

Roland Hanna (the title track of a well-wrought 2001 homage to<br />

Oscar Pettiford): “<strong>Ron</strong> is an innovator and, as this solo bore out, a great<br />

storyteller. Probably 99.9 percent of the bass players out here play stuff<br />

from <strong>Ron</strong>. There’s Paul Chambers, and you can go back to Pettiford,<br />

Blanton and Israel Crosby, and a few people after Chambers—but a lot<br />

of it culminated in <strong>Ron</strong>, and then after <strong>Ron</strong> it’s all of us. <strong>Ron</strong> to me is<br />

the most important bass player of the last 50 years. He defined the role<br />

of the bass player.”<br />

This remark summarizes the general consensus among Clarke’s<br />

peers. On other Blindfold Tests, John Patitucci praised the “the architecture<br />

of [<strong>Carter</strong>’s] lines,” his “blended sound” and “great sense of<br />

humor when he plays”; William Parker mentioned <strong>Carter</strong>’s penchant<br />

for “not playing a lot of notes” and “keeping a bass sound on his bass”;<br />

Andy Gonzalez noted his “shameless quotes of tiny pieces of melody<br />

from all kinds of obscure songs, which you have to know a lot of music<br />

to do”; and Eric Revis said, “He’s gotten to the place where there’s<br />

<strong>Ron</strong>isms that you expect, and only he can do them.”<br />

Generations of musicians have closely analyzed <strong>Carter</strong>’s ingenious<br />

walking bass lines on the studio albums and live recordings he made<br />

between 1963 and 1968 with Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie<br />

Hancock and Tony Williams, who considered it their mandate to relax<br />

the rules of the 32-bar song form as far as possible while still maintaining<br />

the integrity of the tune in question (as heard on the 2011 Columbia/<br />

Legacy box set Live In Europe 1967: The Bootleg Series Vol. 1, which<br />

won Historical Album of the Year in the DownBeat Readers Poll).<br />

They’ve paid equivalent attention to the several dozen iconic Blue<br />

Note and CTI dates on which the bassist accompanied the likes of<br />

Shorter, Joe Henderson, McCoy Tyner, Freddie Hubbard, Stanley<br />

Turrentine, Milt Jackson and Antônio Carlos Jobim. They’re on intimate<br />

terms with <strong>Carter</strong>’s creative, definitive playing with a host of<br />

trios—grounding Bobby Timmons’ soul unit in the early ’60s; performing<br />

the equilateral triangle function with Williams and Hancock<br />

or Hank Jones, and with Billy Higgins and Cedar Walton; or navigating<br />

the wide-open spaces with Bill Frisell and Paul Motian—on which<br />

he incorporates a host of extended techniques into the flow with a tone<br />

that has been described as “glowing in the dark.” They’re cognizant of<br />

<strong>Carter</strong>’s uncanny ability to shape-shift between soloistic and complementary<br />

functions with such rarefied duo partners as Walton, Jim Hall,<br />

Kenny Barron and, more recently, Richard Galliano, Rosa Passos and<br />

Houston Person. They respect his extraordinarily focused contributions<br />

to hundreds of commercial studio dates on which, as <strong>Carter</strong> puts it, “I<br />

maintain my musical curiosity about the best notes while being able to<br />

deliver up the product for this music as they expected to hear it in the<br />

30 seconds I have to make this part work.”<br />

Not least, <strong>Carter</strong>’s admirers know his work as a leader, with an<br />

oeuvre of more than 30 recordings in a host of configurations, including<br />

a half-dozen between 1975 and 1990 by a two-bass quartet in which<br />

either Buster Williams or Leon Maleson took on the double bass duties,<br />

allowing <strong>Carter</strong> to function as a front-line horn with the piccolo bass,<br />

tuned in the cello register.<br />

<strong>Carter</strong> first deployed this concept in 1961 on his debut recording,<br />

Where, with a quintet including Eric Dolphy, Mal Waldron and Charlie<br />

Persip in which he played cello next to bassist George Duvivier. A son<br />

of Detroit, <strong>Carter</strong> played cello exclusively from ages 10 to 17, exhibiting<br />

sufficient talent to be “the first black kid” in the orchestra at Interlochen<br />

Center for the Arts’ music camp (in Interlochen, Mich.), and then burnishing<br />

his skills at Cass Tech, the elite arts-oriented high school that<br />

produced so many of the Motor City’s most distinguished musicians.<br />

“Jazz was always in the air at school, but it wasn’t my primary listening,”<br />

<strong>Carter</strong> said. “I had other responsibilities—the concert band,<br />

the marching band, the orchestra, my chores at home and maintaining<br />

a straight-A average. We were playing huge orchestrations of Strauss,<br />

Beethoven and Brahms, and the Bach cantatas with all these voices<br />

moving in and out.” Midway through <strong>Carter</strong>’s senior year, it became<br />

clear to him that more employment would accrue if he learned to play<br />

the bass—a decision reinforced when he heard “Blue Haze,” a blues in<br />

F on which Miles Davis’ solo unfolds over a suave Percy Heath bass<br />

line and Art Blakey’s elemental beat on the hi-hat, ride cymbal and<br />

bass drum. “I was fascinated to hear them making their choices sound<br />

superb with the bare essentials,” <strong>Carter</strong> said. “These three people were<br />

generating as much musical logic in six to eight choruses as a 25-minute<br />

symphony with 102 players.”<br />

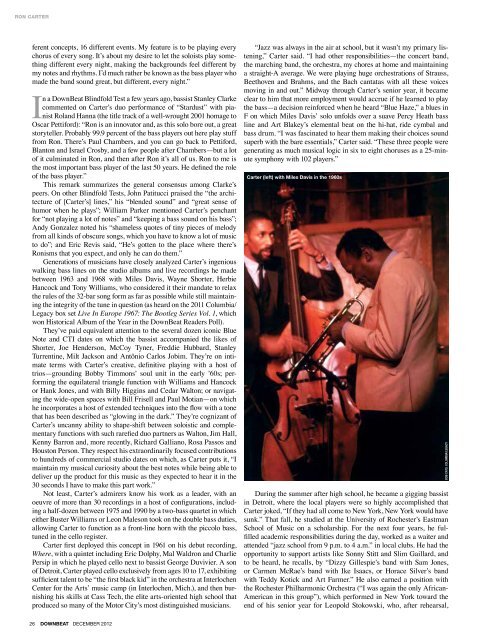

<strong>Carter</strong> (left) with Miles Davis in the 1960s<br />

During the summer after high school, he became a gigging bassist<br />

in Detroit, where the local players were so highly accomplished that<br />

<strong>Carter</strong> joked, “If they had all come to New York, New York would have<br />

sunk.” That fall, he studied at the University of Rochester’s Eastman<br />

School of Music on a scholarship. For the next four years, he fulfilled<br />

academic responsibilities during the day, worked as a waiter and<br />

attended “jazz school from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m.” in local clubs. He had the<br />

opportunity to support artists like Sonny Stitt and Slim Gaillard, and<br />

to be heard, he recalls, by “Dizzy Gillespie’s band with Sam Jones,<br />

or Carmen McRae’s band with Ike Isaacs, or Horace Silver’s band<br />

with Teddy Kotick and Art Farmer.” He also earned a position with<br />

the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra (“I was again the only African-<br />

American in this group”), which performed in New York toward the<br />

end of his senior year for Leopold Stokowski, who, after rehearsal,<br />

bob cato, columbia/legacy<br />

26 DOWNBEAT DECEMBER 2012