Ron Carter Esperanza Spalding - Downbeat

Ron Carter Esperanza Spalding - Downbeat

Ron Carter Esperanza Spalding - Downbeat

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

RON CARTER<br />

Steven sussman<br />

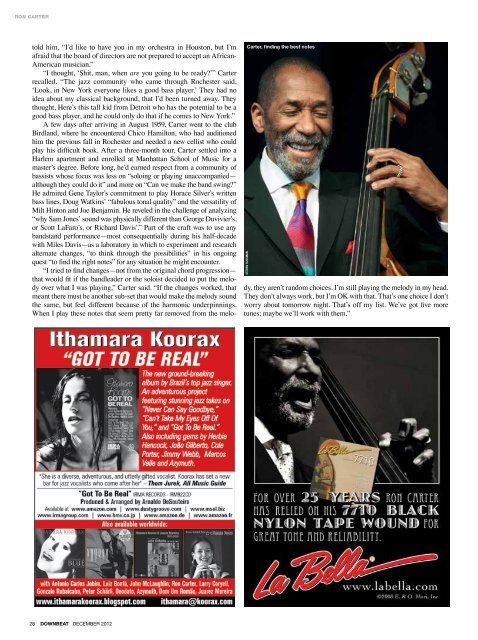

<strong>Carter</strong>, finding the best notes<br />

told him, “I’d like to have you in my orchestra in Houston, but I’m<br />

afraid that the board of directors are not prepared to accept an African-<br />

American musician.”<br />

“I thought, ‘Shit, man, when are you going to be ready?’” <strong>Carter</strong><br />

recalled. “The jazz community who came through Rochester said,<br />

‘Look, in New York everyone likes a good bass player.’ They had no<br />

idea about my classical background, that I’d been turned away. They<br />

thought, Here’s this tall kid from Detroit who has the potential to be a<br />

good bass player, and he could only do that if he comes to New York.”<br />

A few days after arriving in August 1959, <strong>Carter</strong> went to the club<br />

Birdland, where he encountered Chico Hamilton, who had auditioned<br />

him the previous fall in Rochester and needed a new cellist who could<br />

play his difficult book. After a three-month tour, <strong>Carter</strong> settled into a<br />

Harlem apartment and enrolled at Manhattan School of Music for a<br />

master’s degree. Before long, he’d earned respect from a community of<br />

bassists whose focus was less on “soloing or playing unaccompanied—<br />

although they could do it” and more on “Can we make the band swing?”<br />

He admired Gene Taylor’s commitment to play Horace Silver’s written<br />

bass lines, Doug Watkins’ “fabulous tonal quality” and the versatility of<br />

Milt Hinton and Joe Benjamin. He reveled in the challenge of analyzing<br />

“why Sam Jones’ sound was physically different than George Duvivier’s,<br />

or Scott LaFaro’s, or Richard Davis’.” Part of the craft was to use any<br />

bandstand performance—most consequentially during his half-decade<br />

with Miles Davis—as a laboratory in which to experiment and research<br />

alternate changes, “to think through the possibilities” in his ongoing<br />

quest “to find the right notes” for any situation he might encounter.<br />

“I tried to find changes—not from the original chord progression—<br />

that would fit if the bandleader or the soloist decided to put the melody<br />

over what I was playing,” <strong>Carter</strong> said. “If the changes worked, that<br />

meant there must be another sub-set that would make the melody sound<br />

the same, but feel different because of the harmonic underpinnings.<br />

When I play these notes that seem pretty far removed from the melody,<br />

they aren’t random choices. I’m still playing the melody in my head.<br />

They don’t always work, but I’m OK with that. That’s one choice I don’t<br />

worry about tomorrow night. That’s off my list. We’ve got five more<br />

tunes; maybe we’ll work with them.”<br />

28 DOWNBEAT DECEMBER 2012