The Inflation Cycle of 2002 to 2015 - Uhlmann Price Securities

The Inflation Cycle of 2002 to 2015 - Uhlmann Price Securities

The Inflation Cycle of 2002 to 2015 - Uhlmann Price Securities

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

For a printed copy <strong>of</strong> this report, contact your Legg Mason account representative.<br />

Equity Research<br />

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong><br />

We Began With “Do Commodity-Serving Companies Deserve Your Capital?”<br />

• We believe that inflation versus deflation is underappreciated as a determinant <strong>of</strong> sec<strong>to</strong>r selection success.<br />

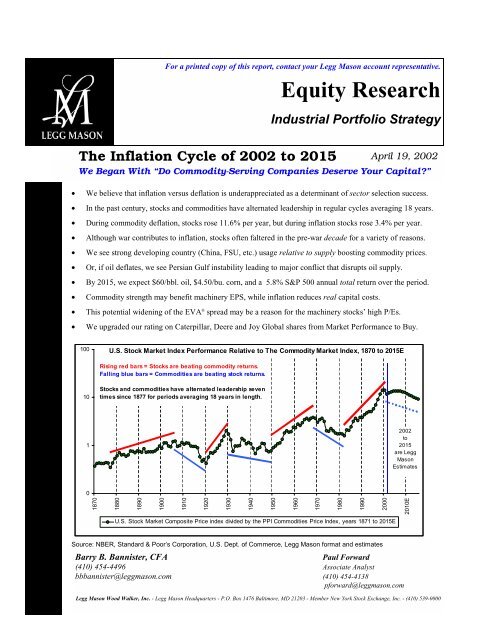

• In the past century, s<strong>to</strong>cks and commodities have alternated leadership in regular cycles averaging 18 years.<br />

• During commodity deflation, s<strong>to</strong>cks rose 11.6% per year, but during inflation s<strong>to</strong>cks rose 3.4% per year.<br />

• Although war contributes <strong>to</strong> inflation, s<strong>to</strong>cks <strong>of</strong>ten faltered in the pre-war decade for a variety <strong>of</strong> reasons.<br />

• We see strong developing country (China, FSU, etc.) usage relative <strong>to</strong> supply boosting commodity prices.<br />

• Or, if oil deflates, we see Persian Gulf instability leading <strong>to</strong> major conflict that disrupts oil supply.<br />

• By <strong>2015</strong>, we expect $60/bbl. oil, $4.50/bu. corn, and a 5.8% S&P 500 annual <strong>to</strong>tal return over the period.<br />

• Commodity strength may benefit machinery EPS, while inflation reduces real capital costs.<br />

• This potential widening <strong>of</strong> the EVA ® spread may be a reason for the machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks’ high P/Es.<br />

April 19, <strong>2002</strong><br />

• We upgraded our rating on Caterpillar, Deere and Joy Global shares from Market Performance <strong>to</strong> Buy.<br />

100<br />

U.S. S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Index Performance Relative <strong>to</strong> <strong>The</strong> Commodity Market Index, 1870 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E<br />

Rising red bars = S<strong>to</strong>cks are beating commodity returns.<br />

Falling blue bars = Commodities are beating s<strong>to</strong>ck returns.<br />

10<br />

S<strong>to</strong>cks and commodities have alternated leadership seven<br />

times since 1877 for periods averaging 18 years in length.<br />

1<br />

<strong>2002</strong><br />

<strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>2015</strong><br />

are Legg<br />

Mason<br />

Estimates<br />

0<br />

1870<br />

1880<br />

1890<br />

1900<br />

1910<br />

1920<br />

1930<br />

1940<br />

1950<br />

1960<br />

1970<br />

1980<br />

1990<br />

2000<br />

U.S. S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Composite <strong>Price</strong> index divided by the PPI Commodities <strong>Price</strong> Index, years 1871 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E<br />

2010E<br />

Source: NBER, Standard & Poor’s Corporation, U.S. Dept. <strong>of</strong> Commerce, Legg Mason format and estimates<br />

Barry B. Bannister, CFA<br />

Paul Forward<br />

(410) 454-4496 Associate Analyst<br />

bbbannister@leggmason.com (410) 454-4138<br />

pforward@leggmason.com<br />

Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc. - Legg Mason Headquarters - P.O. Box 1476 Baltimore, MD 21203 - Member New York S<strong>to</strong>ck Exchange, Inc. - (410) 539-0000

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -2- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Table <strong>of</strong> Contents<br />

Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………….……… 5 – 6<br />

Report Conclusion: “His<strong>to</strong>ry Doesn’t Repeat Itself, But It Does Rhyme” – Mark Twain………7 – 25<br />

S<strong>to</strong>ck Rating Changes……………………………..…………………………………………… 8 – 15<br />

<strong>Inflation</strong> As a Trade-Off Between Hard Assets and Financial Assets……………………….. 16 – 23<br />

<strong>The</strong> Structure <strong>of</strong> This Report ..….……………………………………………………………..… 24 – 25<br />

Scenario (1) Continued Deflation, the U.S. Equity Bull Market, and Strong “Tech”<br />

Capital Spending: Probability: 15%……………………………………………………………………26 – 38<br />

Continued Deflation?………………………………………………………………………...… 26<br />

<strong>The</strong> His<strong>to</strong>rical Parallels in Monetary Policy His<strong>to</strong>ry………………...…………………….. 26 – 27<br />

Money Supply Growth and Deteriorating Velocity as Precursors <strong>of</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> ..…………. 27 – 29<br />

<strong>The</strong> Outlook for Domestic Productivity as An Offset To Loose Monetary Policy……….. 29 – 30<br />

<strong>The</strong> Outlook for Productivity Improvement Overseas That Affects U.S. Competitiveness. 30 – 32<br />

<strong>The</strong> Commodity <strong>Price</strong> Sensitivity <strong>of</strong> the U.S. Economy…………………………………….… 32 – 35<br />

Continuation <strong>of</strong> the Bull Market and Strong “Tech” Spending (?)...………………………… 35 – 37<br />

<strong>The</strong> End <strong>of</strong> the Status Quo?……………...…………………………………………………..… 38<br />

Scenario (2) Rapid Developing Country Modernization And Global Economic Growth Leading<br />

To a Sustained and <strong>Inflation</strong>ary Boom in Commodity Demand: Probability: 60%…….…….39 – 62<br />

Will Surging Demand Create Peacetime Commodity <strong>Inflation</strong>?…….……………………… 39 – 40<br />

<strong>The</strong> Energy <strong>Price</strong> Drivers, 1870 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E………………………...…………….…………… 40 – 43<br />

<strong>The</strong> Demand Side <strong>of</strong> the Oil Equation – <strong>The</strong> 2001 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> Environment……. ..………..… 43<br />

<strong>The</strong> China Example – Pushing the Oil Demand Envelope…………………….…………… 43 – 45<br />

<strong>The</strong> Supply Side <strong>of</strong> the Oil Equation – <strong>The</strong> 2001 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> Environment.…………………… 45 – 48<br />

Substitute Fuels – Promising, But Enough <strong>to</strong> Make a Difference?…………………………... 49 – 50<br />

U.S. Farm Commodity Export and <strong>Inflation</strong> Prospects, <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E…………………... 51 – 62<br />

U.S. Farm Commodity <strong>Price</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong>s…………………...…………….……………………..… 51 – 53<br />

<strong>The</strong> U.S. Farm Export Outlook………….………………………...…………….…………… 53 – 57<br />

U.S. Agricultural Exports and Deere S<strong>to</strong>ck……………………………….…. ..…………… 57 – 58<br />

<strong>The</strong> Global Competitiveness <strong>of</strong> the U.S. Farm Economy….…………………….…………. 58 – 62<br />

Scenario (3) Middle East War(s) in the Period <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> That Result in Extended Oil<br />

Supply Disruptions: Probability: 25%………………………………………………………...… 63 – 81<br />

<strong>The</strong> Risk <strong>of</strong> U.S. Military Action <strong>to</strong> Change the Iraqi Regime That May<br />

Lead <strong>to</strong> a Destabilized Region…………………………………………….………………….. 65 – 66<br />

<strong>The</strong> Risk That Iraq Has or Will Soon Succeed in the Development<br />

<strong>of</strong> Nuclear Weapons………………………………………………...……………….….…….66 – 69<br />

<strong>The</strong> Risk <strong>of</strong> Civil War That Targets Saudi Arabia's Ruling al-Saud Monarchy ..…………..69 – 74<br />

<strong>The</strong> Risk <strong>of</strong> Conventional (Non-Nuclear) War Between States in the Region……………... 74 – 77<br />

<strong>The</strong> Risk <strong>of</strong> Terrorists Obtaining Nuclear Weapons Developed in the Soviet Union……...78

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -3- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Non-Economic Contrasts Between East and West That Affect the Investment Outlook... 79 – 81<br />

Political and Cultural Differences Between East and West………………………………..… 79 – 80<br />

Areas <strong>of</strong> Instability in the Political and Cultural Relations Between East and West………. 80 – 81<br />

<strong>The</strong> Fork in the Road – Inves<strong>to</strong>rs are Along For the Ride………………….…. ..…………. 81<br />

Index <strong>of</strong> Exhibits<br />

Exhibit 1 – <strong>The</strong> S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Versus Machinery and the S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Versus Commodities,<br />

1945 <strong>to</strong> 2001 - Is this a new, secular bull market for machinery?…………..…………………. 8<br />

Exhibit 2 – Machinery Index (CAT+DE+IR+PH) <strong>Price</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong>s, January 1981 <strong>to</strong> Present…...…….…. 9<br />

Exhibit 3 – Machinery Index (CAT+DE+IR+PH) <strong>Price</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong>s, January 1965 <strong>to</strong> April 1981.…….…. 10<br />

Exhibit 4 – CAT Financial His<strong>to</strong>ry and Our Projections <strong>to</strong> 2006, including EVA…….……………….. 11<br />

Exhibit 5 – CAT <strong>Price</strong>-<strong>to</strong>-Sales Multiple Versus EVA, 1970 <strong>to</strong> 2006P…………………....……………. 12<br />

Exhibit 6 – DE s<strong>to</strong>ck Versus U.S. Farm Exports, 1962 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E…………………………….……….….. 13<br />

Exhibit 7 – U.S. Electricity Generation By Fuel Source, 1920-2001, Total and % Share By Fuel.…... 15<br />

Exhibit 8 – Coal <strong>Price</strong>s Versus S<strong>to</strong>ck <strong>Price</strong>s, real (index year 2000) prices, 1901 <strong>to</strong> 2001….………… 15<br />

Exhibit 9 – <strong>Inflation</strong> and Deflation <strong>Cycle</strong>s, 1898 <strong>to</strong> 2001……………………………………….…….…... 16<br />

Exhibit 10 – PPI All Commodities Index Y/Y % Change Compared <strong>to</strong> the PPI Subindices for<br />

Energy, Farm Products and Metals, 1870 <strong>to</strong> 2001…….…………………………………………... 17<br />

Exhibit 11 – Machinery Purchasers XOM, PD, IP and HM Fixed Asset Replacement Rate Versus<br />

Average Remaining Useful Life Of Property, Plant and Equipment, 1950 <strong>to</strong> 2001…..………. 18<br />

Exhibit 12 – PPI for All Commodities Index, 1870 <strong>to</strong> 2001, With Our Forecast <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>……………... 19<br />

Exhibit 13 – U.S. S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Index, 1870 <strong>to</strong> 2001, With Our Forecast <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>…………………….. 19<br />

Exhibit 14 – U.S. CPI <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong>s, 1880 <strong>to</strong> 2001, With Our <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> Estimates………….…. 20<br />

Exhibit 15 – S<strong>to</strong>ck Returns Minus <strong>Inflation</strong>, 1880 <strong>to</strong> 2001, with our <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> Estimates………... 21<br />

Exhibit 16 – <strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong>-Adjusted U.S. S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Index, M2 Money Supply, and U.S. Consumer<br />

<strong>Price</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong>, <strong>The</strong> 1901 and 1933 <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> Turning Points +/- 12 Years……………... 22<br />

Exhibit 16 Cont’d. – <strong>Inflation</strong>-Adjusted U.S. S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Index, M2 Money Supply, and U.S.<br />

Consumer <strong>Inflation</strong>, <strong>The</strong> 1963 and 2001(E) <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> Turning Points +/- 12 Years…….. 23<br />

Exhibit 17 – Return and Growth Table for Commodities, S<strong>to</strong>cks and <strong>Inflation</strong>, <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E……….. 25<br />

Exhibit 18 – M2 Money Supply Vs. Consumer <strong>Inflation</strong>, 10-Year Moving Avg., 1880 <strong>to</strong> 2001……….. 28<br />

Exhibit 19 – M2 Velocity Versus Consumer <strong>Inflation</strong>, 10-Year Moving Average, 1880 <strong>to</strong> 2001………. 28<br />

Exhibit 20 – M2 Velocity Versus CPI <strong>Inflation</strong>, 1960 <strong>to</strong> 2001………………………………………………. 29<br />

Exhibit 21 – U.S. Productivity Growth Versus Demographic Measures: <strong>The</strong> Ratio <strong>of</strong> Experienced Workers<br />

<strong>to</strong> Less Experienced Workers as a Driver For U.S. Productivity Growth………………………. 30<br />

Exhibit 22 – Comparative Demographic Trends That We Believe Shape Productivity, the Ratio <strong>of</strong> 35-49<br />

Year Olds <strong>to</strong> 20-34 Year Olds, China, Japan and the U.S., 1950 <strong>to</strong> 2050E………………...…….. 31<br />

Exhibit 23 – U.S. End-Use Energy as a Percentage <strong>of</strong> GDP……………………………………………..…... 32<br />

Exhibit 24 – U.S. Home Size Versus Energy Costs……………………………………………………………. 33<br />

Exhibit 25 – Long-Term Temperature Trends And Energy <strong>Price</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong>……………………………….... 34<br />

Exhibit 26 – S&P Composite P/E Ratios And <strong>Inflation</strong> Based On the Experience <strong>of</strong> the Period 1927<br />

<strong>to</strong> 2001..…………………………………………………………………………………………………... 35<br />

Exhibit 27 – S&P S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Composite Average Annual P/E, 1927 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>(E)……………………... 36<br />

Exhibit 28 – U.S. Financing Gap, 1952 <strong>to</strong> Present……………………………………………………………. 37<br />

Exhibit 29 – <strong>The</strong> Declining Ability Of Debt <strong>to</strong> Underpin U.S. GDP Growth……………………………... 39<br />

Exhibit 30 – Raw Materials Intensity At Different Stages <strong>of</strong> Economic Development………………….. 39

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -4- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Exhibit 31 – PPI Energy <strong>Price</strong> His<strong>to</strong>ry and Supply/Demand Drivers, 1870 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E...………………... 41<br />

Exhibit 32 – Oil Consumption Per Capita Versus Oil Intensity <strong>of</strong> GDP, 62 Nations, As Of Year 2000 42<br />

Exhibit 33 – Oil Consumption Per Capita for Japan, South Korea, and China, 1950-2001……………. 44<br />

Exhibit 34 – U.S. Oil Consumption vs. GDP, 1902 <strong>to</strong> 2001, and for China, 1975 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E…………... 45<br />

Exhibit 35 – World Oil Supply And Demand His<strong>to</strong>ry and Our Projection <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>……………………... 46<br />

Exhibit 36 – Oil Export-Based Economies as Share <strong>of</strong> World Oil Production, 1965-<strong>2015</strong>E…………… 47<br />

Exhibit 37 – Non-OPEC Reserve-To-Production Ratio, 1952 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E…………………………………... 47<br />

Exhibit 38 – Net Exports and Imports <strong>of</strong> Oil, and Oil <strong>Price</strong>s, 1965-<strong>2015</strong>E..……………………………… 48<br />

Exhibit 39 – Deere S<strong>to</strong>ck Is Driven By Food Exports………………………………………………………. 51<br />

Exhibit 40 – <strong>The</strong> PPI <strong>Price</strong> His<strong>to</strong>ry and Our Estimates For U.S. Agriculture, 1870 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E…………. 52<br />

Exhibit 41 – Deere S<strong>to</strong>ck Is Not Driven By Farm Aid……………………………………………………… 53<br />

Exhibit 42 – Grain Import Hubs Shift Over Time………………………………………………………….. 54<br />

Exhibit 43 – <strong>The</strong> Transition from Old <strong>to</strong> New Grain Markets……………………………………………. 54<br />

Exhibit 44 – U.S. Grain Trade Market Share……………………………………………………………….. 55<br />

Exhibit 45 – Key Drivers In Meat Product Trade…………………………………………………………... 56<br />

Exhibit 46 – Deere S<strong>to</strong>ck Follows Trac<strong>to</strong>r Sales Trends…………………………………………………... 58<br />

Exhibit 47 – U.S. Farm Acres and Farm Commodity Pricing……………………………………………... 58<br />

Exhibit 48 – Food Exports Help Drive Food <strong>Price</strong>s………………………………………………………... 59<br />

Exhibit 49 – Currency Moves Inversely <strong>to</strong> Food Exports………………………………………………….. 59<br />

Exhibit 50 – U.S. Corn Yields, +/(-) 10% From Trend…………………………………………………….. 60<br />

Exhibit 51 – U.S. Corn Yields and Fertilizer Usage………………………………………………………... 60<br />

Exhibit 52 – Deere S<strong>to</strong>ck and Corn <strong>Price</strong>s…………………………………………………………………... 62<br />

Exhibit 53 – Persian Gulf Oil as a Percentage <strong>of</strong> U.S. Consumption, 1970 <strong>to</strong> 2001……………………. 64<br />

Exhibit 54 – Persian Gulf Oil Exports in Real (Year 2000) U.S. Dollars, 1970 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E…………….. 64<br />

Discussion: Iraq’s Potential Approach <strong>to</strong> Nuclear Weapons………………………………………………. 66<br />

Exhibit 55 – Cumulative Effect <strong>of</strong> Oil <strong>Price</strong> Swings on Wealth Transfer, 1970 <strong>to</strong> 2001E……………... 70<br />

Discussion: A Brief His<strong>to</strong>ry <strong>of</strong> Saudi Arabia and the al Saud Royal Family…………………………….. 71<br />

Exhibit 56 – Saudi Arabian GNP Per Capita and Urbanization………………………………………..…... 73<br />

Exhibit 57 – Saudi Arabia Youth Wave, 1974 <strong>to</strong> 2040E……………………………………………….……. 73<br />

Exhibit 58 – Middle East Map………………………………………………………………………………….. 74<br />

Exhibit 59 – <strong>The</strong> Persian Gulf Military Balance in 2001 ………………………………………………….... 75<br />

Exhibit 60 – Military Quality versus Quantity in the Persian Gulf, 2001….………………………….…... 75<br />

Appendix A – U.S. <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong>s From a Monetary His<strong>to</strong>ry Perspective, 1898 <strong>to</strong> 2001……….... ….. 82<br />

Appendix B – Caterpillar Inc. Data Used To Build EVA Model, 1970 <strong>to</strong> 2006E………………………... 85

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -5- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Executive Summary<br />

By <strong>2015</strong>, we estimate prices <strong>of</strong> $60 per barrel for oil, $4.50 per bushel for corn, and a 5.8% S&P 500<br />

annual <strong>to</strong>tal return (0.4% after inflation) point-<strong>to</strong>-point from <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>. Since a reduction <strong>of</strong> S&P<br />

500 prospective returns lowers the opportunity cost <strong>of</strong> capital for machinery companies, and machinery EPS<br />

are <strong>of</strong>ten enhanced when the commodity producers they serve have pricing power, we upgraded our rating<br />

on the shares <strong>of</strong> Caterpillar Inc. (CAT), Deere and Company (DE) and Joy Global Inc. (JOYG) from<br />

Market Performance <strong>to</strong> Buy. In short, we believe that a secular bull market has begun for commodities<br />

and commodity-serving companies, with the normal peaks and valleys along the way. We are keeping some<br />

powder dry and deferring a Strong Buy rating on the basis <strong>of</strong> current valuation, the seasonality <strong>of</strong> machinery<br />

s<strong>to</strong>ck performance (which <strong>of</strong>ten peaks in May and bot<strong>to</strong>ms in Oc<strong>to</strong>ber), as well as our concern that gradually<br />

but steadily rising inflation, which is the view we describe in this report, ultimately will destabilize the<br />

prevailing market sentiment, which we believe retains a long-duration asset bias. <strong>The</strong> Fed has allowed a<br />

money supply “mountain” <strong>to</strong> build in recent years, and investments that benefit from even modest inflation,<br />

such as machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks, have a small capitalization relative <strong>to</strong> the liquidity that now seeks them. For that<br />

reason, as well as the positive spread between commodity industry-leveraged machinery company EPS and<br />

declining machinery company real capital costs as a result <strong>of</strong> inflation, we would expect machinery valuation<br />

multiples <strong>to</strong> remain high even as EPS recover, rather than compress rapidly as EPS rise, which is the<br />

his<strong>to</strong>rical norm. We believe that the machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks we upgraded would be especially attractive if they<br />

were <strong>to</strong> retrench, all else being equal, but despite their recent price run, CAT and DE s<strong>to</strong>cks are still within<br />

the multiyear trading range that began after the previous earnings peak in 1997 <strong>to</strong> 1998. We expect the<br />

s<strong>to</strong>cks we upgraded <strong>to</strong> lurch out <strong>of</strong> that multiyear trading range sometime in 2003.<br />

For a sense <strong>of</strong> his<strong>to</strong>ry, many commodity producers and the machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks serving them enjoyed a<br />

“secular” bull market from June 1970 <strong>to</strong> April 1981, but the festivities ended with the collapse <strong>of</strong> a commodity<br />

bubble around 1980, just as the Fed moved <strong>to</strong> break inflation, and OPEC overplayed its pricing<br />

hand, causing commodity prices <strong>to</strong> tumble. After a painful economic adjustment in 1980–82, the old inflation<br />

beneficiaries <strong>of</strong> the 1970s attempted a false rally in 1982–83, but quickly yielded price leadership <strong>to</strong><br />

the new “disinflation” plays. S<strong>to</strong>cks received a further boost around 1990 when the U.S.S.R. collapsed in a<br />

heap around the same time the U.S. military defeated Iraq in the Gulf War, creating a decade-long peace<br />

dividend, fiscal policy cover for an “easy money” Fed, and U.S. hegemony in the Persian Gulf that ensured<br />

cheap oil for years <strong>to</strong> come. We believe that the post-Gulf War “New World Order” began <strong>to</strong> unravel<br />

in 2000, signaled by the NASDAQ composite and then the S&P 500 rolling over, and we do not believe<br />

it was a coincidence that commodity prices and machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks beginning <strong>to</strong> rise around the<br />

same time.<br />

Commodity-serving machinery generally underperformed in the 1982 <strong>to</strong> 2000 period we described. But in<br />

his<strong>to</strong>rical terms, a shift from the 1982 <strong>to</strong> 2000 equity bull market <strong>to</strong> a new period <strong>of</strong> stronger commodity<br />

prices and, presumably, machinery s<strong>to</strong>ck performance, is completely normal. S<strong>to</strong>cks and commodities, in<br />

fact, have alternated relative and absolute price leadership in cycles averaging 18 years for over a century.<br />

Since 1870, and excluding dividends, U.S. s<strong>to</strong>ck prices rose 11.6% per year during deflation cycles and<br />

3.4% per year during inflation cycles. Commodity price bubbles tend <strong>to</strong> burst (ca. 1920, 1950, 1980) after<br />

military (or economic) warfare and before equity bull markets, the latter <strong>of</strong> which usually feature declining<br />

commodity input costs that improve business pr<strong>of</strong>it margins, falling inflation that increases the P/E multiple<br />

applied <strong>to</strong> those earnings, and rising debt ratios facilitated by cheaper credit. We do not find those "growth"

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -6- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

markets <strong>to</strong> be receptive <strong>to</strong> machinery s<strong>to</strong>ck investing, generally speaking. Alternatively, when s<strong>to</strong>ck price<br />

bubbles begin <strong>to</strong> deflate or burst (ca. 1909, 1929, 1968, 2000), inflation cycles usually follow, largely because<br />

legacy debt must be reduced via some combination <strong>of</strong> inflation, increased export growth, or default,<br />

and the dislocation <strong>of</strong> this transition <strong>of</strong>ten leads <strong>to</strong> an “easy” monetary policy and, unfortunately, <strong>to</strong> military<br />

or economic warfare. <strong>The</strong> U.S. was embroiled in major (lengthy and global) periods <strong>of</strong> hot or economic<br />

warfare for 26% <strong>of</strong> the 20th century. Although war contributed greatly <strong>to</strong> inflation, s<strong>to</strong>cks <strong>of</strong>ten faltered in<br />

the pre-war decade for several reasons, the most common <strong>of</strong> which was excessive money supply growth<br />

relative <strong>to</strong> GDP as the central bankers sought <strong>to</strong> assuage debt problems or fight <strong>of</strong>f wars.<br />

We embarked on our report because we believe that the greatest rewards for inves<strong>to</strong>rs accrue <strong>to</strong> those who<br />

are best positioned for the era's big winners, not the occasional cyclical or product growth s<strong>to</strong>ry. This report<br />

is organized as a probability array <strong>of</strong> expected values, based on what we believe are the three most plausible<br />

<strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> outcomes that shape the inflation and market returns picture, which, in turn, shapes the machinery<br />

sales outlook, in our view. We use over 100 years <strong>of</strong> his<strong>to</strong>rical precedent (since 1898) as the<br />

“effect,” and our assessment <strong>of</strong> facts and our forecasts as the “cause.” For such a long forecast period, we<br />

would expect some combination <strong>of</strong> these events, so a probability analysis seems the best approach, in our<br />

view. Of course, the scenarios are not mutually exclusive; for example, increased trade could forestall the<br />

risk <strong>of</strong> war. <strong>The</strong> scenarios we analyze are as follows.<br />

Scenario (1) Continued price disinflation/deflation, the Western-dominated status quo, resumption <strong>of</strong><br />

the technology capital expenditure boom, and prolonged strength for U.S. equity index returns<br />

(probability 15%). In the current cycle, we believe that a reliance on short-term debt has developed, and<br />

we also note the unsustainable divergence between rising debt as a percentage <strong>of</strong> U.S. GDP and the falling<br />

nominal GDP growth derived from that debt, which causes us <strong>to</strong> believe that the Fed will not be as aggressive<br />

raising rates this cycle. That is bullish for machinery, in our view, because the Fed's aggressive rate<br />

hikes in the mid-1990s helped cap the recovery in machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks despite generally strong EPS at the<br />

time.<br />

Scenario (2) Rapid developing country modernization and recovering U.S. growth that results in<br />

strong and sustained commodity demand relative <strong>to</strong> more inelastic supply (probability 60%). We analyze<br />

commodity supply and demand cycles since 1870, as well as the intensity <strong>of</strong> commodity use during<br />

those phases in which economies modernize and then mature. We believe that the world is in a transition<br />

from slack <strong>to</strong> generally tight oil supply, the result <strong>of</strong> strong Asian oil demand, recovering Former Soviet<br />

Union internal usage despite rising production, and the absence <strong>of</strong> any new “North Sea-sized” non-OPEC,<br />

price-spoiling, discoveries. Whereas OPEC's ability <strong>to</strong> constrict supply was the “oil weapon” <strong>of</strong> the 1970s,<br />

we believe that the key <strong>to</strong> OPEC's strength in the coming years will be its rising share in filling world demand<br />

for oil.<br />

Scenario (3) Major wars produce high inflation, and even minor wars can interrupt trade, so we devote<br />

a section <strong>of</strong> this report <strong>to</strong> analyzing the potential for major conflict in the Persian Gulf that may<br />

constrict oil supply (probability 25%). New<strong>to</strong>n's Third Law <strong>of</strong> Motion states, "For every action, there is<br />

an equal and opposite reaction.” We believe that the downward force applied <strong>to</strong> the Persian Gulf as a result<br />

<strong>of</strong> oil deflation may lead <strong>to</strong> an upward explosion <strong>of</strong> war, fueled by the unfortunate recruitment <strong>of</strong> increasingly<br />

young, disenfranchised male populations by radical leaders making a bid for power. We analyze the<br />

Persian Gulf risks we see, <strong>to</strong> include those involving Iraq, civil war risk in Saudi Arabia, and other threats.

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -7- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Report Conclusion: “His<strong>to</strong>ry Doesn’t Repeat Itself, But It Does<br />

Rhyme” – Mark Twain<br />

This report began with the question “Do commodity-serving companies, which have generally been<br />

poor investments since the early 1980s, deserve inves<strong>to</strong>rs’ capital in the coming decade?” Commodityserving<br />

companies generally perform best when commodity supply is tight and/or demand is strong, which<br />

generally has not been the case since 1981. <strong>The</strong> chart on the cover <strong>of</strong> this report shows that the U.S. s<strong>to</strong>ck<br />

market and the Producer <strong>Price</strong> Index for commodities have alternated leadership seven times since 1877, in<br />

cycles averaging 18 years, and the hard asset versus financial asset trade-<strong>of</strong>f is clearly driven by inflation.<br />

From 1982 <strong>to</strong> 2000, commodity prices deflated relative <strong>to</strong> the S&P 500, and the commodity-serving industries<br />

generally underperformed in that period.<br />

After deliberating on this subject since the growth s<strong>to</strong>ck bubble burst in 1Q00, we have come <strong>to</strong> the<br />

conclusion that the inflation cycle is currently turning up, and we further conclude that this is generally<br />

bullish for the s<strong>to</strong>cks <strong>of</strong> companies that serve the commodity producers (and, <strong>of</strong> course, the producers themselves).<br />

We believe signs include surging real estate prices, strong money supply growth, oil and gold<br />

strength, increasing geopolitical instability that may lead <strong>to</strong> inflationary warfare, and a potential peaking <strong>of</strong><br />

the trade-weighted U.S. dollar. While deflation benefits companies with high unit growth and negative pricing<br />

(e.g., computers, s<strong>of</strong>tware), inflation benefits companies with operating leverage and pricing power.<br />

Throughout this report we use the term deflation in lieu <strong>of</strong> “disinflation,” but the intent is the same.<br />

We believe a forward-looking approach, if correct, allows inves<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> position themselves for outsized<br />

investment returns. Positioning is the key word, because analysts are one- or two-trick ponies ins<strong>of</strong>ar<br />

as they are generally “wedded” (for richer or poorer) <strong>to</strong> one or two narrow industry groups, and even<br />

non-specialist inves<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>of</strong>ten require several years <strong>to</strong> build sec<strong>to</strong>r expertise. Foresight is, <strong>of</strong> course, difficult,<br />

but adversity <strong>of</strong>ten has commensurate reward. For example, in 1970, when Middle East troubles were<br />

brewing (after the 1967 war but before the 1973 war) and OPEC (founded in Iraq in 1960) was little known,<br />

a forecast that called for oil <strong>to</strong> rise tenfold <strong>to</strong> $30 per barrel within a decade would have been outlandish. In<br />

1980, near the height <strong>of</strong> inflation, a prediction <strong>of</strong> double-digit real bond yields in less than a decade would<br />

have seemed absurd. In 1990, when technology s<strong>to</strong>cks were “value” s<strong>to</strong>cks because their earnings were<br />

volatile (sound familiar?), a prediction <strong>of</strong> a greater-than-tenfold increase <strong>to</strong> over 5,000 for the NASDAQ<br />

composite within a decade would have seemed ludicrous. But in each <strong>of</strong> those cases, inves<strong>to</strong>rs able <strong>to</strong> anticipate<br />

the environment were well positioned <strong>to</strong> capitalize on the changes. For the period <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>,<br />

we expect a macro-backdrop for our s<strong>to</strong>cks (and the market) with the following features.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

Strong nominal GDP growth, with a large real (ex-inflation) GDP component in the first half <strong>of</strong><br />

the <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> period, and a larger inflation component in the second half <strong>of</strong> the period.<br />

Sharply rising GDP leading <strong>to</strong> Fed rate hikes, but the Fed may have little choice but <strong>to</strong> return <strong>to</strong><br />

an accommodative stance due <strong>to</strong> the “hangover” <strong>of</strong> past financial excesses and, potentially, war.<br />

Strong global commodity demand and commodity prices; poor pr<strong>of</strong>its have discouraged commodity<br />

producer investment since around 1981, and Persian Gulf instability may constrict supply.<br />

Commodity price pressure that contributes <strong>to</strong> higher consumer inflation, or, in the case <strong>of</strong> commodity-consuming<br />

industries with excess capacity, cost pressure may compress pr<strong>of</strong>it margins.

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -8- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

<br />

<br />

<br />

We expect the PPI All Commodities index <strong>to</strong> outpace the S&P 500 over the <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> period;<br />

we see commodity outperformance particularly strong later in the period.<br />

We see single-digit compounded S&P 500 price returns over the <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> period, as the focus<br />

shifts from liquidity plus rising P/Es <strong>to</strong> falling P/Es plus EPS growth driving earnings “power.”<br />

<strong>Inflation</strong> could be made significantly worse if increasing geopolitical instability leads <strong>to</strong> wars in<br />

the <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> period, possibly in the volatile Middle East where pressures are intense.<br />

S<strong>to</strong>ck Rating Changes<br />

As a result <strong>of</strong> our research and the preparation <strong>of</strong> this report, we have upgraded our rating on Caterpillar<br />

Inc. (CAT – $54.92), Deere & Company (DE – $43.25), and Joy Global (JOYG – $16.25) shares<br />

from Market Performance <strong>to</strong> Buy, since machinery tracks the relative strength <strong>of</strong> commodity prices,<br />

shown in Exhibit 1. Although none <strong>of</strong> the s<strong>to</strong>cks appear inexpensive <strong>to</strong> us on our 2003 estimates, they are<br />

Exhibit 1 – <strong>The</strong> S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Versus Machinery (Black Line) and the S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Versus<br />

Commodities (Green Line), 1945 <strong>to</strong> 2001 - Is this a new, secular bull market for machinery?<br />

3.00<br />

2.50<br />

2.00<br />

Note the red and blue lines <strong>of</strong> alternating s<strong>to</strong>ck<br />

market and commodity price leadership correspond<br />

<strong>to</strong> the cover chart <strong>of</strong> this report.<br />

S&P beats machinery<br />

and<br />

S&P beats commodities<br />

12.00<br />

?<br />

10.00<br />

8.00<br />

6.00<br />

1.50<br />

S&P beats machinery<br />

and<br />

S&P beats commodities<br />

Machinery beats S&P<br />

and<br />

Commodities beat S&P<br />

4.00<br />

1.00<br />

2.00<br />

0.50<br />

0.00<br />

1945<br />

1950<br />

1955<br />

1960<br />

1965<br />

1970<br />

1975<br />

1980<br />

1985<br />

1990<br />

1995<br />

2000<br />

S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Relative <strong>to</strong> Machinery<br />

S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Relative <strong>to</strong> Commodities<br />

Source: U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Commerce, Standard & Poor’s Corporation

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -9- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

moderately attractive because <strong>of</strong> their leverage <strong>to</strong> the environment we expect in the coming years. For example,<br />

Caterpillar is the leading provider <strong>of</strong> engines used in the production and movement <strong>of</strong> hydrocarbons, as<br />

well as the leading provider <strong>of</strong> heavy machinery used <strong>to</strong> extract minerals or build basic infrastructure in<br />

many emerging markets, a number <strong>of</strong> which are commodity producers. Deere & Company is the leading provider<br />

<strong>of</strong> farm machinery in the world, and Joy Global has a leading position in electric shovels and underground<br />

coal mining equipment. Our posture since 2000 with respect <strong>to</strong> CAT and DE has been <strong>to</strong> trade the<br />

s<strong>to</strong>cks within a price range until EPS began <strong>to</strong> recover. Both CAT and DE have performed well since 3Q00,<br />

around the same time the price <strong>of</strong> the S&P 500 began <strong>to</strong> decline, which we do not believe is coincidental<br />

since that is around the same time the secular changes we outline in this report began <strong>to</strong> emerge. We turned<br />

neutral on CAT and DE in December 2001 as a result <strong>of</strong> macroeconomic “balance sheet” concerns that have<br />

since been overshadowed by aggressive (preinflationary?) policy bandages applied <strong>to</strong> the “cash flow” side <strong>of</strong><br />

the economy.<br />

Exhibit 2 – Machinery Index (CAT+DE+IR+PH) <strong>Price</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong>s, January 1981 <strong>to</strong> Present<br />

250.00<br />

200.00<br />

150.00<br />

100.00<br />

50.00<br />

Secular<br />

peak<br />

Apr. 1981<br />

Trading<br />

Range<br />

CAT+DE+IR+PH Combined S<strong>to</strong>ck <strong>Price</strong> Jan-1981 <strong>to</strong> Present<br />

A pull-back is possible,<br />

our view.<br />

"Cyclical"<br />

+150%<br />

July 1984 <strong>to</strong><br />

May 1990<br />

vs. S&P 500 up<br />

140% in the same<br />

period.<br />

Trading<br />

Range<br />

"Cyclical"<br />

+293%<br />

Aug. 1992 <strong>to</strong><br />

Mar. 1998 vs. S&P<br />

500 up 223% in the<br />

same period.<br />

Trading<br />

Range<br />

0.00<br />

1981<br />

1982<br />

1983<br />

1984<br />

1985<br />

1986<br />

1987<br />

1988<br />

1989<br />

1990<br />

1991<br />

1992<br />

1993<br />

1994<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

<strong>2002</strong><br />

Source: S&P CompuStat, Legg Mason<br />

<strong>The</strong> machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks have enjoyed a considerable rally since they bot<strong>to</strong>med in 3Q00, although the<br />

group has not yet broken out <strong>of</strong> the roughly four-year trading range in which it has been locked. As shown in<br />

Exhibit 2, if there is “only” a post-recession, cyclical recovery in s<strong>to</strong>re for machinery, similar <strong>to</strong> the July<br />

1984 <strong>to</strong> May 1990 period (+150% absolute performance and +10% relative <strong>to</strong> the S&P 500), or perhaps<br />

August 1992 <strong>to</strong> March 1998 (+293% absolute and +70% relative), then we may see a mild pullback before a<br />

multiyear recovery begins. As a result, we are keeping some powder dry and deferring a Strong Buy rating<br />

until we see lower s<strong>to</strong>ck prices or a more sustainable EPS recovery on the horizon, all else being<br />

equal.<br />

Our greater interest, and the subject <strong>of</strong> this report, is a secular, long-term s<strong>to</strong>ry that may be brewing<br />

for commodities. Since such a s<strong>to</strong>ry is tied <strong>to</strong> the inflation outlook, we are mindful that there may be numerous<br />

market dislocations if the inflation mentality changes, and those dislocations may provide lower prices

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -10- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Exhibit 3 – Machinery Index (CAT+DE+IR+PH) <strong>Price</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong>s, January 1965 <strong>to</strong> April 1981<br />

55.00<br />

50.00<br />

45.00<br />

40.00<br />

CAT+DE+IR+PH Combined S<strong>to</strong>ck <strong>Price</strong> Jan-1965 <strong>to</strong> Apr-1981<br />

"Secular"<br />

+221% Machinery<br />

Jun. 1970 <strong>to</strong> Apr. 1981<br />

vs. S&P S<strong>to</strong>ck Composite +83% in<br />

same period.<br />

35.00<br />

30.00<br />

25.00<br />

Trading<br />

Range<br />

20.00<br />

15.00<br />

1965<br />

1966<br />

1967<br />

1968<br />

1969<br />

1970<br />

1971<br />

1972<br />

1973<br />

1974<br />

1975<br />

1976<br />

1977<br />

1978<br />

1979<br />

1980<br />

1981<br />

Source: S&P CompuStat, Legg Mason<br />

for new inves<strong>to</strong>rs in machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks, even though the group may outperform on a relative basis since it<br />

has his<strong>to</strong>rically benefited from commodity inflation. For example, in Exhibit 3 we show the secular bull<br />

market for the machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks in our index during the 1970s, when the group rose 221% from June 1970<br />

<strong>to</strong> April 1981, versus only an 83% increase for the S&P 500. We note in the chart the sharp price decline<br />

for our machinery index after the 1973 <strong>to</strong> 1974 OPEC oil embargo and related recession/bear market, and<br />

the sharp rebound when markets realized that machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks were a beneficiary <strong>of</strong> the inflation that was<br />

created. Potential dislocations may include falling bond prices if <strong>2002</strong> GDP growth is sharply higher, some<br />

Fed rate hikes, commodity and CPI inflation pressure, Middle East political instability, and overseas economic<br />

woes. In addition, as an element <strong>of</strong> caution, machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks are seasonal, <strong>of</strong>ten peaking in May and<br />

bot<strong>to</strong>ming in Oc<strong>to</strong>ber, per our research, so we are cautious in a seasonal sense. Lastly, Exhibit 3 shows<br />

that machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks in bullish cycles do have price dips along the way, so we are patient. But we believe<br />

that a longer-term horizon justifies a Buy rating, however, and if there is a pullback in the interim, it may<br />

warrant a Strong Buy rating for CAT, DE or JOYG s<strong>to</strong>ck, all else being equal.<br />

Caterpillar’s vertical integration makes it the quintessential operating leverage play in machinery, in<br />

our view. Our approach <strong>to</strong> CAT and all machinery s<strong>to</strong>cks is <strong>to</strong> separate the “P” from the “E” in the P/E ratio.<br />

In Exhibit 4, we provide a long-term analysis <strong>of</strong> CAT in terms <strong>of</strong> sales, pr<strong>of</strong>it margins, EPS and, most<br />

importantly in our view, Economic Value Added (EVA ® ), which is the excess <strong>of</strong> return on capital over the<br />

cost <strong>of</strong> capital employed. (Supporting data for these charts are contained in Appendix B.) Starting from the<br />

<strong>to</strong>p left, we forecast that by 2006, CAT’s consolidated sales and revenue growth should climb <strong>to</strong> the<br />

his<strong>to</strong>rical average. In the <strong>to</strong>p right chart, our view is that CAT’s net pr<strong>of</strong>it margin as a percent <strong>of</strong> sales and<br />

revenues should benefit from cost reduction and recovering commodity markets, with a potentially weaker

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -11- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Exhibit 4 – CAT Financial His<strong>to</strong>ry and Our Projections <strong>to</strong> 2006, including EVA<br />

25.0%<br />

21.0%<br />

17.0%<br />

13.0%<br />

9.0%<br />

5.0%<br />

1.0%<br />

-3.0%<br />

-7.0%<br />

-11.0%<br />

-15.0%<br />

CAT Sales & Revenue, 3-Year Growth, 1950-2006E<br />

We estimate<br />

moderate sales<br />

growth <strong>to</strong> 2006.<br />

50<br />

52<br />

54<br />

56<br />

58<br />

60<br />

62<br />

64<br />

66<br />

68<br />

70<br />

72<br />

74<br />

76<br />

78<br />

80<br />

82<br />

84<br />

86<br />

88<br />

90<br />

92<br />

94<br />

96<br />

98<br />

00<br />

02E<br />

04E<br />

06E<br />

CAT Sales and Revenues, 3-Year Moving Average Growth Rate<br />

LM<br />

Ests.<br />

13.0%<br />

11.0%<br />

9.0%<br />

7.0%<br />

5.0%<br />

3.0%<br />

1.0%<br />

-1.0%<br />

-3.0%<br />

-5.0%<br />

-7.0%<br />

CAT Consolidated Net Pr<strong>of</strong>it Margin, 1950 <strong>to</strong> 2006E<br />

We estimate net margin<br />

<strong>to</strong> recover substantially<br />

by 2006.<br />

50<br />

52<br />

54<br />

56<br />

58<br />

60<br />

62<br />

64<br />

66<br />

68<br />

70<br />

72<br />

74<br />

76<br />

78<br />

80<br />

82<br />

84<br />

86<br />

88<br />

90<br />

92<br />

94<br />

96<br />

98<br />

00<br />

02E<br />

04E<br />

06E<br />

CAT Consolidated Net Pr<strong>of</strong>it Percent <strong>of</strong> Sales and Revenues<br />

LM<br />

Ests.<br />

$10.00<br />

$1.00<br />

$0.10<br />

CAT EPS (Excl. Loss Years), 1963 <strong>to</strong> 2006E<br />

We expect EPS <strong>to</strong><br />

recover on a log scale<br />

<strong>to</strong> a <strong>to</strong>p-<strong>of</strong>-trend level<br />

by 2006.<br />

L<br />

O<br />

S<br />

S<br />

E<br />

S<br />

63<br />

65<br />

67<br />

69<br />

71<br />

73<br />

75<br />

77<br />

79<br />

81<br />

83<br />

85<br />

87<br />

89<br />

91<br />

93<br />

95<br />

97<br />

99<br />

01<br />

03E<br />

05E<br />

L<br />

O<br />

S<br />

S<br />

E<br />

S<br />

LM<br />

Ests.<br />

NOPAT ROIC Minus WACC<br />

12.00%<br />

10.00%<br />

8.00%<br />

6.00%<br />

4.00%<br />

2.00%<br />

0.00%<br />

(2.00%)<br />

(4.00%)<br />

(6.00%)<br />

(8.00%)<br />

(10.00%)<br />

(12.00%)<br />

(14.00%)<br />

(16.00%)<br />

(18.00%)<br />

Caterpillar EVA (%) Each Year, 1970 <strong>to</strong> 2001 Actual<br />

With Our <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> 2006 Estimates and Projections<br />

EVA finally recovers significantly<br />

through 2006 in our model.<br />

1970<br />

1972<br />

1974<br />

1976<br />

1978<br />

1980<br />

1982<br />

1984<br />

1986<br />

1988<br />

1990<br />

1992<br />

1994<br />

1996<br />

1998<br />

2000<br />

<strong>2002</strong>E<br />

2004E<br />

2006E<br />

Caterpillar EPS (Log Scale, Excludes Loss Years)<br />

(20.00%)<br />

Source: Company reports, Moody’s Industrial Manuals, Standard and Poor’s Corporation, Legg Mason estimates. EVA is a registered<br />

U.S. dollar as well. As a result, by 2006, we foresee a 9.6% net pr<strong>of</strong>it margin, eclipsing the 8.8% peak<br />

achieved in 1997, thus rivaling the best <strong>of</strong> the post-World War II years, since CAT is significantly more<br />

lean and well managed after 20 years <strong>of</strong> surviving hardship, in our view. Multiplying the results from the<br />

preceding charts, and dividing by shares outstanding, in the bot<strong>to</strong>m left chart we show CAT’s EPS tracking<br />

<strong>to</strong> a potential “cyclical peak” level <strong>of</strong> about $8.00 by 2006. In the bot<strong>to</strong>m right chart, we show the net<br />

operating pr<strong>of</strong>it after taxes (NOPAT) return on invested capital (ROIC) comfortably rising above the<br />

weighted average cost <strong>of</strong> capital (WACC), generating positive EVA in the <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> 2006 period.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a clear relationship between CAT’s s<strong>to</strong>ck price as a multiple <strong>of</strong> consolidated sales and<br />

revenues per share (i.e., P/S) and CAT’s EVA, shown in Exhibit 5. By analyzing the period 1970 <strong>to</strong><br />

2006E in our chart, we capture most <strong>of</strong> one entire inflation cycle (the 1970s), one deflation cycle (1980s<br />

and 1990s), and the beginnings <strong>of</strong> what we view <strong>to</strong> be another moderate inflation cycle (the first five years

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -12- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

Exhibit 5 – CAT <strong>Price</strong>-<strong>to</strong>-Sales Multiple Versus EVA, 1970 <strong>to</strong> 2006E<br />

1.30<br />

CAT <strong>Price</strong>/Sales vs. Annual EVA , 1970 <strong>to</strong> 2006P<br />

(1997 (Prior EPS Peak) = Black Circle; 2000 (Cyclical Trough <strong>Price</strong>) = Blue Triangle; Current <strong>Price</strong>/Sales Multiple on<br />

2003E = Red Circle, Current <strong>Price</strong>/Sales on 2006P Potential Cyclical Peak = Green Square)<br />

<strong>Price</strong> / Sales Multiple<br />

1.20<br />

1.10<br />

1.00<br />

0.90<br />

0.80<br />

0.70<br />

0.60<br />

0.50<br />

0.40<br />

0.30<br />

0.20<br />

0.10<br />

CAT's price/sales multiple versus<br />

EVA guides our full-cycle trading<br />

range expectations.<br />

0.00<br />

(18.00%) (15.00%) (12.00%) (9.00%) (6.00%) (3.00%) 0.00% 3.00% 6.00% 9.00% 12.00%<br />

Caterpillar Annual EVA % (NOPAT ROIC minus WACC)<br />

2003E<br />

2000<br />

1997<br />

2006P<br />

Source: Moody’s Industrial Manual, Company reports, Legg Mason <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> 2006 estimates<br />

<strong>of</strong> 2001 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>). Of course, part <strong>of</strong> Caterpillar’s improvement in EVA since the absolute trough in 1984 is<br />

that CAT has developed a large finance company, which tends <strong>to</strong> lower the WACC but increase debt leverage.<br />

Largely for that reason, Caterpillar’s consolidated debt divided by the market value <strong>of</strong> equity rose from<br />

48% in 1984 <strong>to</strong> 97% in 2001. At CAT’s prior cyclical peak EPS ($4.37) in 1997, the company’s EVA was<br />

584 basis points, and the P/S multiple was 0.97x, shown in Exhibit 5 as a black circle. By 2000, at what we<br />

believe <strong>to</strong> be the cyclical trough for CAT’s average annual s<strong>to</strong>ck price ($37.90), CAT inves<strong>to</strong>rs were<br />

positioned for only about 100 basis points, on average, <strong>of</strong> EVA in the subsequent two years, and the P/S in<br />

2000 was only 0.65x, shown by a blue triangle. Currently, CAT s<strong>to</strong>ck trades at a P/S <strong>of</strong> 0.89x our 2003<br />

expectation for sales and revenues per share, with an EVA <strong>of</strong> 100 basis points, shown by a red circle. In<br />

our view, CAT’s 2003 P/S multiple is a bit rich, but does not negate the likelihood <strong>of</strong> positive absolute<br />

returns if one sees CAT nearing cyclical peak EPS in the year 2006. If CAT’s results track as we expect<br />

<strong>to</strong> 2006, then the EPS <strong>of</strong> $8.00 and consolidated sales and revenues <strong>of</strong> $28.9 billion in that year produce a<br />

current P/S multiple (using the current price divided by sales and revenues per share in 2006E) <strong>of</strong> 0.66x,<br />

and an EVA <strong>of</strong> 552 basis points that year.<br />

<strong>The</strong> purchase decision with respect <strong>to</strong> CAT s<strong>to</strong>ck is, <strong>of</strong> course, tied <strong>to</strong> what sort <strong>of</strong> return expectations<br />

satisfy the buyer <strong>of</strong> the shares. We believe CAT s<strong>to</strong>ck could earn a P/S multiple <strong>of</strong> 1.00x in 2006, a<br />

premium <strong>to</strong> the regression line in Exhibit 5, as a result <strong>of</strong> then-expected cyclical optimism, equating <strong>to</strong> a<br />

price <strong>of</strong> $83 in our model ($28.9 billion 2006E sales and revenues divided by 348.5 million shares). This<br />

price is also a P/E just over 10x our “peak” projected level <strong>of</strong> $8.00. From the current price <strong>of</strong><br />

approximately $54.92, that is a price return potential <strong>of</strong> about 11% and a <strong>to</strong>tal return potential <strong>of</strong> 13%<br />

including dividends on an annual basis. We prefer a 20% annual <strong>to</strong>tal return for a Strong Buy rating, which<br />

equates <strong>to</strong> a price <strong>of</strong> $43 for CAT s<strong>to</strong>ck now, all else being equal. Returns are <strong>of</strong>ten relative, however, and

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -13- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

our previous WACC calculations contained a S&P 500 “opportunity cost” price return projection. For the<br />

period <strong>of</strong> this writing <strong>to</strong> 2006, we forecast an annual <strong>to</strong>tal return for the S&P 500 <strong>of</strong> approximately 8.0%<br />

(2.1% dividend reinvested, 5.9% price). CAT s<strong>to</strong>ck appears <strong>to</strong> <strong>of</strong>fer a superior relative <strong>to</strong>tal return <strong>of</strong> over<br />

300 basis points, warranting a Buy rating, in our view. In addition <strong>to</strong> the normal retinue <strong>of</strong> cyclical<br />

economic indica<strong>to</strong>rs in recovery mode, as a nonstandard indica<strong>to</strong>r we also cite the recent strength <strong>of</strong> gold.<br />

Recall that in February 1993 gold prices began <strong>to</strong> rise sharply, and CAT s<strong>to</strong>ck also continued a strong,<br />

cyclical recovery in that year. Later in this report we outline a view that the Greespan Fed depends upon the<br />

U.S. consumer <strong>to</strong> sustain the economic recovery, and since the consumer appears <strong>to</strong> require low interest<br />

rates <strong>to</strong> avoid a painful and abrupt decline in consumer activity, we doubt the Fed will pursue an<br />

aggressive rate policy in <strong>2002</strong>–2003 as it did in the earlier, mid-1990s cyclical economic recovery.<br />

Deere s<strong>to</strong>ck is the quintessential farm economy “macro-play,” in our view. Despite diversification efforts<br />

that <strong>of</strong>ten have proven fruitless, Deere, fortunately, has enhanced its leadership position in farm machinery.<br />

In Exhibit 6, we show that DE s<strong>to</strong>ck tracks U.S. agricultural exports, the latter being driven by a<br />

complex mix <strong>of</strong> global GDP, dietary enrichment, foreign exchange, hydrocarbon input costs, weather, free<br />

trade practices, interest rates, and government payments <strong>to</strong> farmers. But a 20-year period <strong>of</strong> hardship has a<br />

way <strong>of</strong> warping the mindset <strong>of</strong> an industry, and we believe most analyses <strong>of</strong> agriculture are not sufficiently<br />

Exhibit 6 – DE s<strong>to</strong>ck Versus U.S. Farm Exports, 1962 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E<br />

Real U.S. Agricultural Exports ($ Mil.)<br />

$110,000<br />

$100,000<br />

$90,000<br />

$80,000<br />

$70,000<br />

$60,000<br />

$50,000<br />

$40,000<br />

$30,000<br />

$20,000<br />

Deere Performance Tracks U.S. Food Exports<br />

Real Export<br />

CAGR 1962 <strong>to</strong><br />

1996 =<br />

2.7%/year<br />

Machinery industry and farmer over-capacity<br />

plagued pr<strong>of</strong>its, but consolidation resulted.<br />

1962<br />

1964<br />

1966<br />

1968<br />

1970<br />

1972<br />

1974<br />

1976<br />

1978<br />

1980<br />

1982<br />

1984<br />

1986<br />

1988<br />

1990<br />

1992<br />

1994<br />

1996<br />

1998<br />

2000<br />

<strong>2002</strong>E<br />

2004E<br />

LM<br />

Ests.<br />

Real Export<br />

CAGR 1996 <strong>to</strong><br />

<strong>2015</strong>E =<br />

2.4%/year<br />

2006E<br />

2008E<br />

2010E<br />

2012E<br />

2014E<br />

14.0%<br />

12.0%<br />

10.0%<br />

8.0%<br />

6.0%<br />

4.0%<br />

2.0%<br />

Deere Relative <strong>to</strong> the S&P 500<br />

Real U.S. Farm Product Exports, U.S. $ Mil. (Left)<br />

Deere S<strong>to</strong>ck Relative <strong>to</strong> the S&P Composite (Right)<br />

Source: USDA, S&P Compustat, Legg Mason <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> estimates

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -14- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

open <strong>to</strong> the improving conditions. <strong>The</strong> actual trend for real U.S. agricultural exports was 2.7% growth (PPI<br />

index year 2000) from 1962 <strong>to</strong> 1996, and we see real growth <strong>of</strong> only 2.4% from 1996 <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>E, or from<br />

$64.3 billion <strong>of</strong> real U.S. agricultural exports in 1996 ($52.3 billion in current, 2001 dollars) <strong>to</strong> $100 billion<br />

in <strong>2015</strong>. U.S. agricultural exports have been volatile, with inflation-adjusted U.S. agricultural exports rising<br />

from $27 billion in 1969 <strong>to</strong> a peak <strong>of</strong> $67.2 billion in 1980, but then plunging <strong>to</strong> $32.4 billion in 1986. Exports<br />

then climbed <strong>to</strong> a peak <strong>of</strong> $64.3 billion in 1996, on the strength <strong>of</strong> developing country demand and<br />

weather-related supply disruptions, but fell <strong>to</strong> $50.8 billion in 2000 before beginning a gradual recovery.<br />

Generally speaking, we see higher commodity prices, a weaker U.S. dollar, and improved emerging<br />

market economies, all <strong>of</strong> which support export prospects for U.S. farmers, in our view. <strong>The</strong> diminution<br />

<strong>of</strong> European Union (EU) and Former Soviet Union (FSU) grain and meat import markets, which had been<br />

the “s<strong>to</strong>ry” <strong>of</strong> the 1970s and 1980s but burst in the 1990s, is key. While the EU and FSU have contracted,<br />

the “new” markets in the Atlantic, Pacific and Middle East have continued <strong>to</strong> expand, which we believe is<br />

key <strong>to</strong> U.S. export prospects. A weaker U.S. dollar cycle also would assist U.S. farm exports, since U.S. agricultural<br />

exports fell 14.1% from 1995 <strong>to</strong> 2000, as the U.S. farm trade-weighted dollar rose 18.9% in that<br />

period. Since the U.S. farmer competes with currencies that may appreciate along with commodity prices (e.<br />

g., those <strong>of</strong> Canada, Australia, and the FSU), as well as against the low-priced European euro, the stage may<br />

be set for stronger U.S. agricultural exports in the coming decade. <strong>The</strong> U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Agriculture<br />

(USDA) estimates agricultural exports <strong>of</strong> $54.5 billion in <strong>2002</strong>, up 10.8% from the trough <strong>of</strong> $49.2 billion<br />

in 1998, which we see as the beginning <strong>of</strong> a long-term recovery for various reasons outlined later in this report.<br />

As a result, we expect DE s<strong>to</strong>ck <strong>to</strong> outperform the S&P 500 more frequently in the period from <strong>2002</strong><br />

<strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong>.<br />

Although conditions have been less rosy for Deere in terms <strong>of</strong> U.S. agricultural trade since 1981, a favorable<br />

side effect has been farm machinery industry capacity rationalization. As <strong>to</strong>tal U.S. row crop<br />

trac<strong>to</strong>r plus combine harvester unit sales fell from 94,700 units in 1979 <strong>to</strong> 23,482 units in 2001, the farm<br />

machinery industry consolidated <strong>to</strong> a handful <strong>of</strong> global players. Also, the number <strong>of</strong> U.S. farms fell 10.9%<br />

from 1979 <strong>to</strong> 2001, and U.S. planted acreage fell 7.9%. Were it not for farm subsidies, capacity would have<br />

been reduced further, but we note that Deere targets larger, more pr<strong>of</strong>itable farms that tend <strong>to</strong> purchase and<br />

turn over equipment fleets more frequently. We discuss the farm outlook in greater detail later in this report.<br />

We view Joy Global (JOYG) as the quintessential coal play; seeking <strong>to</strong> participate in those cycles, we<br />

upgraded our rating on JOYG s<strong>to</strong>ck from Market Performance <strong>to</strong> Buy. We view JOYG s<strong>to</strong>ck as a<br />

prime beneficiary <strong>of</strong> the recovery <strong>of</strong> the worldwide coal, copper, and steel (via iron ore) prices, as well as<br />

the recent strength in gold mining, since the company is a dominant niche producer <strong>of</strong> electric shovels and<br />

underground coal mining machines. Having emerged from bankruptcy on July 12, 2001, with greatly reduced<br />

debt, Joy Global (formerly known as Harnischfeger Inc.) has been buffeted by an unusually warm<br />

winter that depressed electric utility output, and thus coal mining, since approximately 90% <strong>of</strong> U.S. coal is<br />

used <strong>to</strong> provide electricity, and utilities have accumulated coal inven<strong>to</strong>ry left over from the mild winter. We<br />

note, however, that coal inven<strong>to</strong>ry at electricity producers as a percentage <strong>of</strong> trailing 5-year average annual<br />

usage was 13.9% in 2001, versus 11.1% in 2000, but still below the 10-year average <strong>of</strong> 14.6%. In addition,<br />

electricity utility industrial production has begun <strong>to</strong> recover from the recession. Weak housing, au<strong>to</strong> and<br />

electronics markets also have depressed the copper and steel (iron ore) markets <strong>to</strong> which Joy Global sells,<br />

but those markets appear <strong>to</strong> be resilient and, as we said, we do not wish <strong>to</strong> fight the Fed anymore with respect<br />

<strong>to</strong> those early cycle groups, at least for the time being. Given that Joy’s wagon is tied <strong>to</strong> coal, in Exhibit<br />

7 we show that coal has provided 52% <strong>of</strong> growing U.S. electric power for the past 80 years with an an-

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -15- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

nual standard deviation <strong>of</strong> only 3%, and coal’s<br />

outlook as a domestic, thermally efficient, increasingly<br />

clean source <strong>of</strong> power remains solid,<br />

in our view.<br />

Exhibit 7 – U.S. Electricity Generation By Fuel<br />

Source, 1920-2001, Total and % Share By Fuel<br />

100%<br />

Other<br />

Joy Global has more “low-hanging fruit” costreduction<br />

potential than most machinery makers,<br />

in our opinion, such as inven<strong>to</strong>ry turns <strong>of</strong> only<br />

1.9x (FIFO basis), the improvement <strong>of</strong> which could<br />

reduce Joy Global’s modest 30% net debt <strong>to</strong> capital.<br />

Whether management will improve the company<br />

is difficult <strong>to</strong> say, but the cycle is our main<br />

interest, and the cycle is largely beyond management’s<br />

control, in our opinion. In Exhibit 8, we<br />

show that the inflation-adjusted price <strong>of</strong> coal and<br />

the U.S. s<strong>to</strong>ck market move in opposite directions,<br />

and appear <strong>to</strong> be converging yet again. For more<br />

information on JOYG s<strong>to</strong>ck, we refer inves<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong><br />

our basic report on the company dated September<br />

10, 2001.<br />

90%<br />

80%<br />

70%<br />

60%<br />

50%<br />

40%<br />

30%<br />

20%<br />

10%<br />

0%<br />

1920<br />

1925<br />

1930<br />

1935<br />

1940<br />

1945<br />

1950<br />

Hydroelectric<br />

Gas<br />

Coal<br />

1955<br />

1960<br />

Petroleum<br />

Nuclear<br />

1965<br />

1970<br />

1975<br />

1980<br />

1985<br />

1990<br />

1995<br />

2000<br />

Source: Bureau <strong>of</strong> Labor Statistics;.EIA; U.S. Census Bureau, His<strong>to</strong>rical<br />

Statistics <strong>of</strong> the United States, Colonial Times <strong>to</strong> 1970<br />

Exhibit 8 – Coal <strong>Price</strong>s Versus S<strong>to</strong>ck <strong>Price</strong>s, real (index year 2000) prices, 1901 <strong>to</strong> 2001.<br />

$100.00<br />

Good for coal = bad for s<strong>to</strong>ck prices:<br />

<strong>The</strong>re is a 100 year precedent showing an inverse<br />

relationship between coal prices and the S&P<br />

S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Composite price.<br />

10,000<br />

1,000<br />

Average<br />

2001 coal<br />

spot price<br />

100<br />

$10.00<br />

10<br />

1901<br />

1905<br />

1909<br />

1913<br />

1917<br />

1921<br />

1925<br />

1929<br />

1933<br />

1937<br />

1941<br />

1945<br />

1949<br />

1953<br />

1957<br />

1961<br />

1965<br />

1969<br />

1973<br />

1977<br />

1981<br />

1985<br />

1989<br />

1993<br />

1997<br />

2001<br />

Bituminous Coal FOB Mine, $ per Short Ton, Real (year 2000) <strong>Price</strong>s, Left<br />

S&P S<strong>to</strong>ck Market Composite, Real (year 2000) <strong>Price</strong>s, Right<br />

Source: EIA; U.S. Census Bureau, His<strong>to</strong>rical Statistics <strong>of</strong> the United States, Colonial Times <strong>to</strong> 1970

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -16- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

<strong>Inflation</strong> As a Trade-Off Between Hard Assets and Financial Assets<br />

Until now, we have discussed our conclusions, but now it is time <strong>to</strong> discuss the reasoning behind those<br />

conclusions. Exhibit 9 shows the three U.S. commodity inflation (pre-war and wartime) and deflation periods<br />

<strong>of</strong> the 20th century. We note the following cyclical characteristics and similarities.<br />

<br />

<strong>The</strong> commodity inflation periods averaged 19 years in length, but have grown shorter, and regardless <strong>of</strong><br />

whether the pre-war or war years are examined, the entire period featured generally high money supply<br />

(M2) growth, moderately high or high inflation, and uniformly low s<strong>to</strong>ck market returns.<br />

Exhibit 9 – <strong>Inflation</strong> and Deflation <strong>Cycle</strong>s, 1898 <strong>to</strong> 2001<br />

<strong>Inflation</strong> (Pre-War and War) <strong>Cycle</strong>s CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong><br />

PPI - All PPI PPI M2 Money Real U.S. CPI U.S. S<strong>to</strong>ck<br />

Com- Farm Fuels Supply Economic Urban Market<br />

Start End Yrs. modities Products & Power Growth Growth (1) <strong>Inflation</strong> Index (2)<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> One 1898 <strong>to</strong> 1920 22 5.4% 5.7% 7.3% 7.6% 3.4% 4.1% 2.2%<br />

Pre-war period was: 1898 <strong>to</strong> 1914 16 2.2% 2.9% 3.1% 6.5% 3.9% 1.2% 3.0%<br />

War years were (3) : 1914 <strong>to</strong> 1920 6 14.6% 13.3% 19.4% 10.8% 1.1% 12.2% 0.1%<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> Two 1933 <strong>to</strong> 1951 18 5.6% 7.9% 3.6% 8.2% 5.4% 4.0% 5.6%<br />

Pre-war period was: 1933 <strong>to</strong> 1939 6 2.6% 4.1% 1.6% 7.7% 5.7% 1.2% 5.8%<br />

War years were (4) : 1939 <strong>to</strong> 1951 12 7.1% 9.9% 4.7% 8.5% 5.5% 5.3% 5.5%<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> Three 1965 <strong>to</strong> 1981 16 7.2% 8.1% 13.2% 8.4% 3.4% 6.8% 2.3%<br />

Pre-Oil Embargo (5) was: 1965 <strong>to</strong> 1973 8 4.3% 4.1% 4.4% 7.7% 4.2% 4.4% 2.3%<br />

Oil Embargo(es) were: 1973 <strong>to</strong> 1981 8 10.2% 12.2% 22.8% 9.2% 2.9% 9.4% 2.3%<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> One, Two, and Three Average:<br />

<strong>of</strong> which the pre-war average was:<br />

and the war-related (6) average was:<br />

19 6.1% 7.2% 8.1% 8.1% 4.1% 5.0% 3.4%<br />

10 3.0% 3.7% 3.0% 7.3% 4.6% 2.3% 3.7%<br />

9 10.7% 11.8% 15.6% 9.5% 3.2% 9.0% 2.6%<br />

Deflation (Post-War) <strong>Cycle</strong>s<br />

CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong> CAGR <strong>of</strong><br />

PPI - All PPI PPI M2 Real U.S. CPI U.S. S<strong>to</strong>ck<br />

Com- Farm Fuels Y/Y % Economic Urban Market<br />

Start End Yrs. modities Products & Power Growth Growth (1) <strong>Inflation</strong> Index (2)<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> One 1920 <strong>to</strong> 1933 13 ( 6.3 )% ( 8.0 )% ( 6.7 )% 1.0% 0.1% ( 3.3 )% ( 0.1 )%<br />

Roaring 20s were: 1920 <strong>to</strong> 1929 9 ( 5.2 )% ( 4.0 )% ( 7.2 )% 4.3% 3.6% ( 1.7 )% 12.8%<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> Two 1951 <strong>to</strong> 1965 14 0.4% ( 1.6 )% 0.4% 5.6% 4.0% 1.4% 10.4%<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> Three 1981 <strong>to</strong> 2001 20 1.6% 1.8% 0.4% 5.8% 3.1% 3.4% 11.8%<br />

<strong>Cycle</strong> One, Two, and Three Average (7): 14 ( 1.1 )% ( 1.3 )% ( 2.2 )% 5.2% 3.6% 1.0% 11.7%<br />

(1) For U.S. economic growth, we use real GNP prior <strong>to</strong> 1947, and GDP thereafter, indexed <strong>to</strong> year 2001 U.S. dollars.<br />

(2) This is the U.S. s<strong>to</strong>ck market composite index price return only, and does not include reinvested dividends.<br />

(3) Though World War I ended in 1918, we include 1919 <strong>to</strong> 1920 because the war's commodity bubble and deficit spending continued.<br />

(4) We include the post-World War Two period since price controls were lifted after the war, and the Korean Conflict had some impact.<br />

(5) <strong>The</strong> Great Society "war" on poverty, plus Vietnam, were more regional rather that global in focus, in our view.<br />

(6) Average <strong>of</strong> World Wars I and II, as well as the global economic warfare <strong>of</strong> the Middle East war-related Oil Embargoes <strong>of</strong> the 1970s.<br />

(7) Average <strong>of</strong> Roaring 20s, <strong>Cycle</strong> Two and Three; the deflationary calamity <strong>of</strong> the early 1930s renders comparable analysis meaningless.<br />

Source: Legg Mason, data from U.S. Dept. <strong>of</strong> Commerce, U.S. Census publication “His<strong>to</strong>rical Statistics <strong>of</strong> the United States, Colonial<br />

Times <strong>to</strong> 1970,” Standard and Poor’s Corporation, National Bureau <strong>of</strong> Economic Research macroeconomic database

Industrial Portfolio Strategy<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Inflation</strong> <strong>Cycle</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>2002</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>2015</strong> ⎯ April 19, <strong>2002</strong> -17- Legg Mason Wood Walker, Inc.<br />

<strong>The</strong> commodity inflation cycles were followed by deflation (peace dividend) cycles that averaged 14<br />

years in length, but have grown longer, and featured moderate M2 and real GDP growth, low inflation<br />

and high equity returns.<br />