Tactical Intercepts.pdf - e-HAF

Tactical Intercepts.pdf - e-HAF

Tactical Intercepts.pdf - e-HAF

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

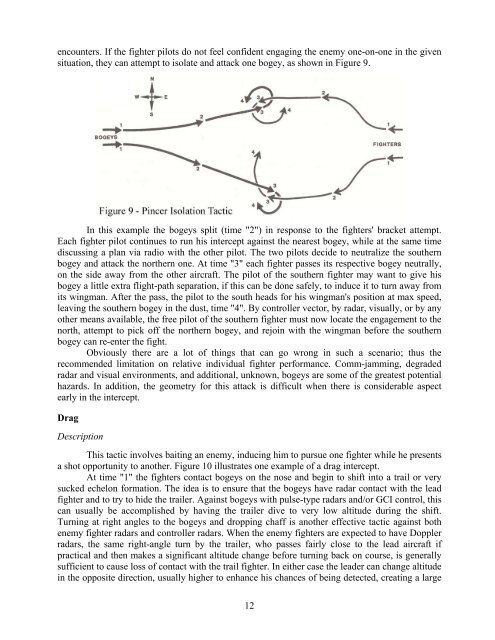

encounters. If the fighter pilots do not feel confident engaging the enemy one-on-one in the given<br />

situation, they can attempt to isolate and attack one bogey, as shown in Figure 9.<br />

In this example the bogeys split (time "2") in response to the fighters' bracket attempt.<br />

Each fighter pilot continues to run his intercept against the nearest bogey, while at the same time<br />

discussing a plan via radio with the other pilot. The two pilots decide to neutralize the southern<br />

bogey and attack the northern one. At time "3" each fighter passes its respective bogey neutrally,<br />

on the side away from the other aircraft. The pilot of the southern fighter may want to give his<br />

bogey a little extra flight-path separation, if this can be done safely, to induce it to turn away from<br />

its wingman. After the pass, the pilot to the south heads for his wingman's position at max speed,<br />

leaving the southern bogey in the dust, time "4". By controller vector, by radar, visually, or by any<br />

other means available, the free pilot of the southern fighter must now locate the engagement to the<br />

north, attempt to pick off the northern bogey, and rejoin with the wingman before the southern<br />

bogey can re-enter the fight.<br />

Obviously there are a lot of things that can go wrong in such a scenario; thus the<br />

recommended limitation on relative individual fighter performance. Comm-jamming, degraded<br />

radar and visual environments, and additional, unknown, bogeys are some of the greatest potential<br />

hazards. In addition, the geometry for this attack is difficult when there is considerable aspect<br />

early in the intercept.<br />

Drag<br />

Description<br />

This tactic involves baiting an enemy, inducing him to pursue one fighter while he presents<br />

a shot opportunity to another. Figure 10 illustrates one example of a drag intercept.<br />

At time "1" the fighters contact bogeys on the nose and begin to shift into a trail or very<br />

sucked echelon formation. The idea is to ensure that the bogeys have radar contact with the lead<br />

fighter and to try to hide the trailer. Against bogeys with pulse-type radars and/or GCI control, this<br />

can usually be accomplished by having the trailer dive to very low altitude during the shift.<br />

Turning at right angles to the bogeys and dropping chaff is another effective tactic against both<br />

enemy fighter radars and controller radars. When the enemy fighters are expected to have Doppler<br />

radars, the same right-angle turn by the trailer, who passes fairly close to the lead aircraft if<br />

practical and then makes a significant altitude change before turning back on course, is generally<br />

sufficient to cause loss of contact with the trail fighter. In either case the leader can change altitude<br />

in the opposite direction, usually higher to enhance his chances of being detected, creating a large<br />

12