Internet Freedom A Foreign Policy Imperative in the Digital Age

Internet Freedom A Foreign Policy Imperative in the Digital Age

Internet Freedom A Foreign Policy Imperative in the Digital Age

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

J U N E2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>By Richard Fonta<strong>in</strong>e and Will Rogers

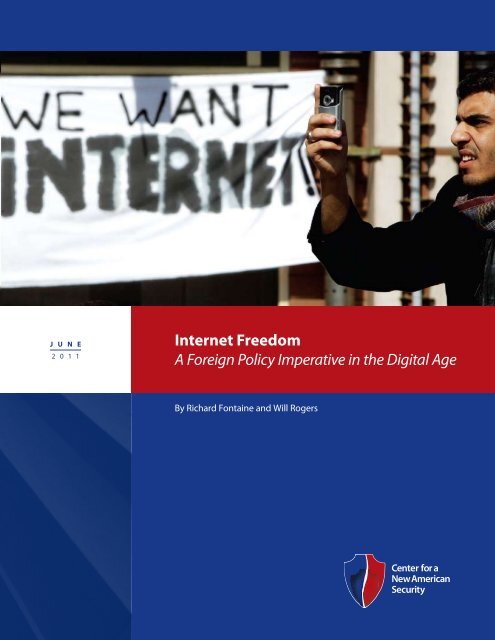

AcknowledgmentsWe express our gratitude to our colleagues at <strong>the</strong> Center for a New American Security (CNAS) for <strong>the</strong>ir assistance with thisstudy. Jackie Koo provided exceptional research assistance throughout <strong>the</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g process. Krist<strong>in</strong> Lord’s efforts <strong>in</strong> edit<strong>in</strong>gand shap<strong>in</strong>g this report and <strong>the</strong> overall CNAS <strong>Internet</strong> freedom project were <strong>in</strong>valuable. Nora Bensahel devoted significanttime and effort to improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g. Liz Fonta<strong>in</strong>e provided typically excellent design and layout help on a shorttimel<strong>in</strong>e.We owe a great deal of thanks to Ambassador David Gross, who shared his unique <strong>in</strong>sights throughout <strong>the</strong> entirety of thisproject. We also owe a large debt of gratitude to those who reviewed all or part of this paper <strong>in</strong> draft form, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g KenBerman, Daniel Cal<strong>in</strong>geart, Andrew Lewman, Sarah Labowitz, Marc Lynch, Rebecca MacK<strong>in</strong>non, Jeff Pryce, Ben Scott andseveral anonymous reviewers. We thank <strong>the</strong> Harvard Law School National Security Research Group for its extraord<strong>in</strong>aryhelp <strong>in</strong> research<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational legal implications of <strong>Internet</strong> freedom. The group, which is directed by Ivana Deyrup,<strong>in</strong>cludes Gracye Cheng, Morgan Cohen, Josh Green, Carlos Oliveira and Mark Stadnyk. F<strong>in</strong>ally, we would like thank <strong>the</strong> manyexperts who patiently spoke with us about <strong>Internet</strong> freedom issues over <strong>the</strong> last year, whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> government, <strong>the</strong> privatesector or academia, here <strong>in</strong> Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, <strong>in</strong> Silicon Valley, or elsewhere.This publication was made possible through <strong>the</strong> support of grants from <strong>the</strong> John Templeton Foundation and <strong>the</strong> MarkleFoundation. The op<strong>in</strong>ions expressed <strong>in</strong> this publication are those of <strong>the</strong> authors and do not necessarily reflect <strong>the</strong> viewsof <strong>the</strong> John Templeton Foundation or <strong>the</strong> Markle Foundation. Readers should note that some organizations that arementioned <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> report or that o<strong>the</strong>rwise have an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> issues discussed here support CNAS f<strong>in</strong>ancially. CNASma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s a broad and diverse group of more than 100 funders, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g private foundations, government agencies, corporationsand private <strong>in</strong>dividuals, and reta<strong>in</strong>s sole editorial control over its ideas, projects and products. A complete list of<strong>the</strong> Center’s f<strong>in</strong>ancial supporters can be found on our website at www.cnas.org/support/our-supporters.The authors of this report are solely responsible for <strong>the</strong> analysis and recommendations conta<strong>in</strong>ed here<strong>in</strong>.Cover ImageA man takes pictures with his cell phone on Tahrir, or Liberation Square, <strong>in</strong> Cairoon January 31, 2011.(BEN CURTIS/Associated Press)

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>About <strong>the</strong> AuthorsRichard Fonta<strong>in</strong>e is a Senior Fellow at <strong>the</strong> Center for a New American Security.Will Rogers is a Research Associate at <strong>the</strong> Center for a New American Security.2 |

<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>: A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>By Richard Fonta<strong>in</strong>e and Will Rogers

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY America needs a comprehensive <strong>Internet</strong> freedomstrategy, one that tilts <strong>the</strong> balance <strong>in</strong> favor of thosewho would use <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> to advance toleranceand free expression, and away from those whowould employ it for repression or violence.By Richard Fonta<strong>in</strong>e and Will RogersThis requires <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom asan <strong>in</strong>tegral element of American foreign policy.As recent events <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Middle East demonstrate,<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> has emerged as a major force <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ternational affairs, one that will have last<strong>in</strong>gimplications for <strong>the</strong> United States and <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternationalcommunity. But new communicationstechnologies are a double-edged sword. Theyrepresent both a medium for <strong>in</strong>dividuals to communicate,form groups and freely broadcast <strong>the</strong>irideas around <strong>the</strong> world, and a tool that empowersauthoritarian governments. U.S. policymakersshould better appreciate <strong>the</strong> complex role newcommunications technologies play <strong>in</strong> politicalchange abroad, and how those technologies<strong>in</strong>tersect with <strong>the</strong> array of American foreign policyobjectives.<strong>Internet</strong> freedom typically <strong>in</strong>cludes two dimensions.<strong>Freedom</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> denotes <strong>the</strong>freedoms of onl<strong>in</strong>e expression, assembly andassociation – <strong>the</strong> extension to cyberspace of rightsthat have been widely recognized to exist outsideit. Promot<strong>in</strong>g freedom of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> merelyexpands to cyberspace a tradition of U.S. diplomaticand f<strong>in</strong>ancial support for human rightsabroad. <strong>Freedom</strong> via <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, <strong>the</strong> notion thatnew communications technologies aid <strong>the</strong> establishmentof democracy and liberal society offl<strong>in</strong>e,is at once more allur<strong>in</strong>g and hotly contested.<strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>in</strong> this sense has captured <strong>the</strong>imag<strong>in</strong>ation of many policymakers and expertswho see <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>se technologies a tool for <strong>in</strong>dividualsto help move <strong>the</strong>ir societies away fromauthoritarianism and toward democracy. Though<strong>the</strong> l<strong>in</strong>ks between democracy and <strong>Internet</strong> freedomare <strong>in</strong>direct and complex, nascent evidencesuggests that new communications tools do| 5

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>6 |matter <strong>in</strong> political change, and that both dissidentsand dictators act on that basis.Most attention has focused on technologies thatallow dissidents to penetrate restrictive firewallsand communicate securely. But fund<strong>in</strong>g technologycomprises just one aspect of America’s<strong>Internet</strong> freedom agenda. The United States alsoadvocates <strong>in</strong>ternational norms regard<strong>in</strong>g freedomof speech and onl<strong>in</strong>e assembly and opposesattempts by autocratic governments to restrictlegitimate onl<strong>in</strong>e activity.The private sector has a critical role to play <strong>in</strong>promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom, but, given corporate<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> maximiz<strong>in</strong>g profits ra<strong>the</strong>r thanpromot<strong>in</strong>g onl<strong>in</strong>e freedom <strong>in</strong> repressive environments,efforts to expand its role are difficult.Ethical debates, rang<strong>in</strong>g from whe<strong>the</strong>r Americancompanies should be permitted to sell repressiveregimes key technologies to <strong>the</strong> responsibilitiesof corporations <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> face of an autocracies’demand for <strong>in</strong>formation, rema<strong>in</strong> unresolved. And<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r side of this co<strong>in</strong> – whe<strong>the</strong>r U.S. exportcontrols should prohibit sell<strong>in</strong>g technologies thatcould be used to promote onl<strong>in</strong>e freedom – isoften overlooked.To date, <strong>the</strong> U.S. government has shied awayfrom articulat<strong>in</strong>g fully <strong>the</strong> motivations beh<strong>in</strong>d its<strong>Internet</strong> freedom agenda. Adm<strong>in</strong>istration officialsemphasize that <strong>the</strong>ir policy supports freedom of<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, not freedom via <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, andthat <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> freedom agenda is not part of abroader strategy to support democratic evolution.It should be.Admittedly, promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom is complicated,and <strong>in</strong>volves <strong>in</strong>herent tensions witho<strong>the</strong>r U.S. foreign policy, economic and nationalsecurity <strong>in</strong>terests. This is particularly true <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>area of cyber security. Cyber security expertsseek to secure <strong>the</strong> United States aga<strong>in</strong>st cyberattacks, for example, by push<strong>in</strong>g for greater onl<strong>in</strong>etransparency and attribution, while <strong>Internet</strong>freedom proponents urge greater onl<strong>in</strong>e anonymity.While tensions between <strong>Internet</strong> freedom andcyber security are real, and <strong>in</strong> some cases will forcedifficult choices, <strong>the</strong>y should not prevent robustU.S. efforts to advance both.A robust <strong>Internet</strong> freedom agenda should reflect<strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g eight pr<strong>in</strong>ciples:Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 1: Embrace a ComprehensiveApproachU.S. policymakers should <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>Internet</strong>freedom <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g (especiallyon cyber security and economic diplomacyissues); convene private sector professionals,export controls experts, diplomats and o<strong>the</strong>rs toexplore new ways of promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom;and use traditional diplomacy to promote<strong>Internet</strong> freedom.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 2: Build an International Coalitionto Promote <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>The U.S. government should convene a core groupof democratic governments to advocate <strong>Internet</strong>freedom <strong>in</strong> key <strong>in</strong>ternational fora; urge governmentsto encourage foreign companies to jo<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Global Network Initiative (GNI); and ensure that<strong>the</strong> Secretary of State gives her next major addresson <strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>in</strong> a foreign country, possibly<strong>in</strong> Europe alongside key European Union (EU)commissioners.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 3: Move Beyond CircumventionTechnologiesThe U.S. government should cont<strong>in</strong>ue to fundtechnologies o<strong>the</strong>r than firewall-evasion tools,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g those that help dissidents ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>digital security, ensure mobile access and reconstitutewebsites after a cyber attack. The U.S.government should offer f<strong>in</strong>ancial awards to fostertechnological <strong>in</strong>novation, require that any onl<strong>in</strong>etool receiv<strong>in</strong>g U.S. fund<strong>in</strong>g be subjected to an<strong>in</strong>dependent security audit and expand <strong>the</strong> sources

of technology fund<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>clude foreign governments,foundations and <strong>the</strong> private sector.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 4: Prioritize Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gThe State Department, along with <strong>the</strong> U.S. <strong>Age</strong>ncyfor International Development (USAID), shouldcont<strong>in</strong>ue to foster <strong>Internet</strong> freedom through targetedtra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g education ononl<strong>in</strong>e safety.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 5: Lead <strong>the</strong> Effort to BuildInternational NormsThe U.S. government should promote a liberalconcept of <strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>in</strong> all relevant fora,and reject attempts by authoritarian states to promotenorms that restrict freedoms of <strong>in</strong>formationand expression onl<strong>in</strong>e. It should also pursue an<strong>in</strong>ternational transparency <strong>in</strong>itiative to encouragegovernments to publicize <strong>the</strong>ir policies on restrict<strong>in</strong>gonl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>formation.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 8: Reform Export ControlsThe U.S. government should relax controls on technologiesthat would permit greater onl<strong>in</strong>e freedomwhile protect<strong>in</strong>g American national security, andeducate companies on <strong>the</strong> precise nature of exportcontrol restrictions so that companies do not overcomplyand deny legal technologies to dissidentsabroad.In addition, we offer several recommendationsfor technology companies, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g provid<strong>in</strong>gdissidents basic technical assistance to better usebuilt-<strong>in</strong> security functions for software and hardware;better <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g users and <strong>the</strong> public aboutwho may access <strong>the</strong> data <strong>the</strong>y control and underwhat conditions; <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g corporate transparencyabout foreign government requests; and advocat<strong>in</strong>gfor <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>Internet</strong> freedom.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 6: Create Economic Incentivesto Support <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>U.S. officials should cont<strong>in</strong>ue to articulate <strong>the</strong>economic case for <strong>Internet</strong> freedom, backed whereverpossible by solid quantitative evidence, andpush for <strong>Internet</strong> censorship to be recognized as atrade barrier.Pr<strong>in</strong>ciple 7: Streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> Private Sector’sRole <strong>in</strong> Support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>Congress should adopt laws that prohibitAmerican corporations from giv<strong>in</strong>g autocraticgovernments <strong>the</strong> private data of dissidents when<strong>the</strong> request is clearly <strong>in</strong>tended to quash legitimatefreedom of expression, and that requirecompanies to periodically disclose requests itreceives for such data to <strong>the</strong> U.S. government.U.S. officials should cont<strong>in</strong>ue to urge companiesto jo<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> GNI, but also encourage <strong>the</strong>mto develop broad unilateral codes of conductconsistent with <strong>the</strong> GNI. They should also publiclyhighlight specific bus<strong>in</strong>ess practices, bothpositive and negative.| 7

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>8 |II. IntroductionThe world’s population is more connected, withmore access to new <strong>in</strong>formation and ideas thanever before. Today, 2 billion people have access to<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>. Five billion people use mobile phones,many of <strong>the</strong>m smartphones with <strong>Internet</strong> access. 1The <strong>Internet</strong> has also become an extension of civilsociety. 2 <strong>Digital</strong> tools are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly used to communicateacross borders, organize protests, launchcyber attacks, build transnational coalitions,topple some dictators and possibly streng<strong>the</strong>no<strong>the</strong>rs – actions that all affect U.S. foreign policy.But American policymakers have just begun to<strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>’s role <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir broaderconceptions of U.S. foreign policy.Thus far, <strong>the</strong> discussion among advocates andforeign policy practitioners has revolved around“<strong>Internet</strong> freedom,” a broad rubric that encompassesonl<strong>in</strong>e freedoms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> rights of expressionand onl<strong>in</strong>e organization, and <strong>the</strong> potentially transformativeand hotly contested role of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong><strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g democratization. The U.S. governmentnow has an <strong>Internet</strong> freedom agenda, withtens of millions of dollars to implement it. Both<strong>the</strong> Senate and <strong>the</strong> House of Representatives boastglobal <strong>Internet</strong> freedom caucuses. The Secretary ofState has given two major addresses articulat<strong>in</strong>gpr<strong>in</strong>ciples and policies for <strong>Internet</strong> freedom, andnewspapers and periodicals have repeatedly po<strong>in</strong>tedto <strong>the</strong> use of onl<strong>in</strong>e tools both for popular protestand as a means of repression. In <strong>the</strong> midst of <strong>the</strong>2011 Arab Spr<strong>in</strong>g, President Obama went so far asto describe <strong>the</strong> ability to use social network<strong>in</strong>g as a“core value” that Americans believe is “universal.” 3The debate over whe<strong>the</strong>r and how to promote<strong>Internet</strong> freedom has been an emotional one, with“cyber utopians” prais<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> as a s<strong>in</strong>gulartool for toppl<strong>in</strong>g dictators, and “cyber pessimists”not<strong>in</strong>g all <strong>the</strong> ways that autocracies use new communicationstools to streng<strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>ir own rule.This report seeks to move beyond <strong>the</strong>se two polesby identify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> nuances and tradeoffs <strong>in</strong>volved<strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g onl<strong>in</strong>e freedom.This study focuses on <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gWeb-based communication platforms such asblogs, social network<strong>in</strong>g and o<strong>the</strong>r photo- andvideo-shar<strong>in</strong>g websites, and proposes an <strong>in</strong>tegrated<strong>Internet</strong> freedom strategy that balancescompet<strong>in</strong>g U.S. <strong>in</strong>terests. 4 We beg<strong>in</strong> by def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>Internet</strong> freedom, dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g between freedomof <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> and freedom via <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, andexam<strong>in</strong>e why <strong>the</strong> United States has an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong> preserv<strong>in</strong>g an open <strong>Internet</strong>. We <strong>the</strong>n exploreways <strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> can be used both fordemocratic political change and as a tool of repression.We argue that <strong>the</strong> United States shouldactively promote <strong>Internet</strong> freedom, given not onlyits potential to aid those seek<strong>in</strong>g liberal politicalchange, but also because do<strong>in</strong>g so accords withAmerica’s deepest values. We exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> U.S.government’s current efforts to promote <strong>Internet</strong>freedom abroad and <strong>the</strong> tensions between <strong>the</strong>seefforts and enhanc<strong>in</strong>g cyber security. F<strong>in</strong>ally, weprovide a set of <strong>in</strong>terlock<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples that, takentoge<strong>the</strong>r, will <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>in</strong>toAmerican foreign policy.The paper assumes that <strong>the</strong> United States has an<strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g human rights and democracyabroad. There is a cont<strong>in</strong>ued healthy debateabout this po<strong>in</strong>t and it is far from America’s only<strong>in</strong>terest. But successive adm<strong>in</strong>istrations (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gthose of Presidents Cl<strong>in</strong>ton, Bush and Obama) havemade promot<strong>in</strong>g democracy an explicit objectiveof U.S. policy. While <strong>the</strong> United States should berealistic and modest about what it can achieve,to <strong>the</strong> extent that a freer onl<strong>in</strong>e space facilitates afreer offl<strong>in</strong>e space, <strong>the</strong> United States should support<strong>Internet</strong> freedom. At its heart, an American<strong>Internet</strong> freedom agenda should actively aim to tilt<strong>the</strong> balance <strong>in</strong> favor of those who would use <strong>the</strong><strong>Internet</strong> to advance tolerance and free expression,and away from those who would use it for repressionor violence.

This paper also acknowledges <strong>the</strong> downsides of<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>. An autocratic regime can use <strong>the</strong><strong>Internet</strong> to streng<strong>the</strong>n its ability to monitor itscitizens and control <strong>the</strong>ir behavior. Terrorists canuse it to communicate and spread propaganda.Crim<strong>in</strong>als can use new technologies to organizeillicit activities. Dissidents can use <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>to spread <strong>the</strong>ir message, but so can extremistsadvocat<strong>in</strong>g violence. There is no certa<strong>in</strong> outcometo this cont<strong>in</strong>ual push and pull, and <strong>the</strong> localpolitical context matters enormously.At its heart, an American<strong>Internet</strong> freedom agendashould actively aim to tilt<strong>the</strong> balance <strong>in</strong> favor of thosewho would use <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>to advance tolerance and freeexpression, and away fromthose who would use it forrepression or violence.This report exam<strong>in</strong>es <strong>Internet</strong> freedom through<strong>the</strong> lens of American foreign policy and explorestwo central questions: What does access to an open<strong>Internet</strong> mean for U.S. foreign policy, and whatshould <strong>the</strong> United States do about it? Our <strong>in</strong>tendedaudience is not merely those <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong>timatelyfamiliar with <strong>Internet</strong> freedom issues, but also thoseforeign policy actors and th<strong>in</strong>kers who should be.As we discuss below, <strong>Internet</strong> freedom means manyth<strong>in</strong>gs to many people, and to some it suggests afocus on domestic policy – net neutrality, antitrustlaw, <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> Federal CommunicationsCommission, and so on. Except where such domesticconcerns impact <strong>Internet</strong> freedom promotionefforts abroad (as we argue <strong>the</strong>y may), such issuesare beyond <strong>the</strong> ambit of this paper.The Center for a New American Security (CNAS)<strong>in</strong>itiated this project <strong>in</strong> March 2010 when it hosted<strong>the</strong> launch of <strong>the</strong> Senate Global <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>Caucus. Over <strong>the</strong> course of more than a year,CNAS <strong>the</strong>n convened a number of work<strong>in</strong>g groupson <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>the</strong> private sector, <strong>the</strong> prospects for<strong>in</strong>ternational normative agreements, <strong>the</strong> role of circumventiontechnology and <strong>the</strong> tensions betweencyber security and <strong>Internet</strong> freedom. In addition,we consulted with representatives <strong>in</strong> government,<strong>the</strong> corporate world, <strong>the</strong> nonprofit sector, technologyfirms and academia. The study was conductedalongside CNAS’ companion project on cybersecurity. 5What is <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>?<strong>Internet</strong> freedom, broadly def<strong>in</strong>ed, is <strong>the</strong> notionthat universal rights, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> freedoms ofexpression, assembly and association, extend to<strong>the</strong> digital sphere. Yet policymakers and o<strong>the</strong>rsoften def<strong>in</strong>e <strong>Internet</strong> freedom differently. It isthus useful to differentiate, as a number of experts<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly have, between two l<strong>in</strong>ked but dist<strong>in</strong>ctconcepts: freedom of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> and freedom via<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>.<strong>Freedom</strong> of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> refers to <strong>the</strong> ability toengage <strong>in</strong> unfettered expression <strong>in</strong> cyberspace.This vision of <strong>Internet</strong> freedom, as scholar EvgenyMorozov po<strong>in</strong>ts out <strong>in</strong> his book The Net Delusion,represents freedom from someth<strong>in</strong>g: censorship,government surveillance, distributed denial ofservice (DDoS) attacks, and so on. 6 The pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesundergird<strong>in</strong>g freedom of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> arearticulated <strong>in</strong> documents such as <strong>the</strong> UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights (UDHR), whichdescribes as <strong>in</strong>alienable <strong>the</strong> right to receive andimpart <strong>in</strong>formation without <strong>in</strong>terference. 7 In thissense, <strong>Internet</strong> freedom is little different from <strong>the</strong>| 9

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>10 |notion of free expression, whose advocacy hasbeen an element of U.S. foreign policy for decades.After all, American ambassadors have long pressedforeign governments to allow a free press, releasejailed journalists and cease jamm<strong>in</strong>g unwantedbroadcasts.<strong>Freedom</strong> via <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> is at once both a moreallur<strong>in</strong>g and complicated idea. Its advocates suggestthat more onl<strong>in</strong>e freedom can lead to moreoffl<strong>in</strong>e freedom; that is, <strong>the</strong> free flow of ideas over<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> promotes democratization. <strong>Freedom</strong>via <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> has captured <strong>the</strong> imag<strong>in</strong>ationof many <strong>in</strong> Congress, <strong>the</strong> media and elsewhere(<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g dissidents and dictators) who havewitnessed <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>’s seem<strong>in</strong>gly transformativeeffects on autocratic governments. Protesters,democratic activists and average citizens are<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly us<strong>in</strong>g Facebook, Twitter and o<strong>the</strong>rapplications to communicate and organize – mostrecently <strong>in</strong> Tunisia and Egypt, but <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r countriesas well.<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong> and U.S. National InterestsThe United States has a long history of provid<strong>in</strong>gdiplomatic and f<strong>in</strong>ancial support for <strong>the</strong> promotionof human rights abroad, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> right to freeexpression. While each presidential adm<strong>in</strong>istrationemphasizes human rights to differ<strong>in</strong>g degrees,dur<strong>in</strong>g recent decades <strong>the</strong>y have all consistentlyheld that human rights are a key U.S. <strong>in</strong>terest.Promot<strong>in</strong>g freedom of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> expands humanrights support <strong>in</strong>to cyberspace, an environment<strong>in</strong> which an ever-greater proportion of humanactivity takes place. The United States advocatesfor freedom of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> because it accords notonly with American values, but also with rightsAmerica believes are <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic to all humanity.For years, <strong>the</strong> U.S. government has programmaticallyand rhetorically supported democracypromotion abroad. The State Department rout<strong>in</strong>elydisburses millions of dollars <strong>in</strong> fund<strong>in</strong>g fordemocracy-build<strong>in</strong>g programs around <strong>the</strong> world,many of which are aimed explicitly at expand<strong>in</strong>gfree expression. Presidential and o<strong>the</strong>r speechesregularly refer to <strong>the</strong> American belief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> universalityof this right; to cite but one example, aMarch 2011 White House statement on Syria notedthat, “The United States stands for a set of universalrights, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> freedom of expression andpeaceful assembly.” 8 The Obama adm<strong>in</strong>istration’s2010 National Security Strategy specifically calledfor marshal<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> and o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong>formationtechnologies to support freedom of expressionabroad, 9 and <strong>the</strong> Bush adm<strong>in</strong>istration adopted apolicy of maximiz<strong>in</strong>g access to <strong>in</strong>formation andideas over <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>. 10America’s <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g freedom via<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> comes from <strong>the</strong> same fundamentalbelief <strong>in</strong> democratic values and human rights.Despite <strong>in</strong>evitable <strong>in</strong>consistencies and difficulttradeoffs, <strong>the</strong> United States cont<strong>in</strong>ues to supportdemocracy. The Bush adm<strong>in</strong>istration’s 2006National Security Strategy committed to supportdemocratic <strong>in</strong>stitutions abroad through transformationaldiplomacy. 11 President Obama, afterenter<strong>in</strong>g office with an evident desire to move awayfrom <strong>the</strong> sweep<strong>in</strong>g tone of his predecessor’s “freedomagenda,” never<strong>the</strong>less told <strong>the</strong> U.N. GeneralAssembly <strong>in</strong> 2009 that “<strong>the</strong>re are basic pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesthat are universal; <strong>the</strong>re are certa<strong>in</strong> truths whichare self-evident – and <strong>the</strong> United States of Americawill never waver <strong>in</strong> our efforts to stand up for <strong>the</strong>right of people everywhere to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong>ir owndest<strong>in</strong>y.” 12To <strong>the</strong> extent that support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedomadvances America’s democracy-promotion agenda,<strong>the</strong> rationale for promot<strong>in</strong>g onl<strong>in</strong>e freedom is clear.However, cause and effect are not perfectly clear and<strong>the</strong> United States must choose its policies under conditionsof uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty. Both <strong>the</strong> Bush and Obamaadm<strong>in</strong>istrations have wagered that by promot<strong>in</strong>gglobal <strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>the</strong> United States will notonly operate accord<strong>in</strong>g to universal values but willpromote tools that may, on balance, benefit societies

over <strong>the</strong> autocrats that oppress <strong>the</strong>m. Secretary ofState Hillary Rodham Cl<strong>in</strong>ton urged countries to“jo<strong>in</strong> us <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> bet we have made, a bet that an open<strong>Internet</strong> will lead to stronger, more prosperouscountries.” 13 Given <strong>the</strong> evidence we discuss throughoutthis report, this bet is one worth mak<strong>in</strong>g.Yet promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>in</strong>evitablyrequires <strong>the</strong> U.S. government to make tradeoffswith o<strong>the</strong>r national security and economic <strong>in</strong>terests– a perennial challenge for a governmentpursu<strong>in</strong>g compet<strong>in</strong>g priorities. After all, it iseasier to support <strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>in</strong> countries<strong>in</strong> which <strong>the</strong> United States discerns few overarch<strong>in</strong>gstrategic and economic <strong>in</strong>terests than <strong>in</strong>countries where <strong>the</strong> United States has a robustand complex agenda.Consider Ch<strong>in</strong>a, for example. Ch<strong>in</strong>a engages <strong>in</strong>widespread <strong>Internet</strong> repression and hosts <strong>the</strong>world’s largest population of onl<strong>in</strong>e users. Butpromot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom <strong>the</strong>re complicatesAmerican efforts to w<strong>in</strong> Beij<strong>in</strong>g’s support on anarray of o<strong>the</strong>r issues, rang<strong>in</strong>g from North Koreato Iran. And streng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g controls over <strong>the</strong> saleof American technologies to Ch<strong>in</strong>a could meanshutt<strong>in</strong>g U.S. companies out of <strong>the</strong> world’s largest<strong>Internet</strong> market at a time when <strong>the</strong> Americaneconomy is still recover<strong>in</strong>g from <strong>the</strong> recentf<strong>in</strong>ancial crisis.The United States should promote <strong>Internet</strong> freedomabroad, but this policy does <strong>in</strong>cur costs.Fund<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>Internet</strong> freedom programs usesscarce dollars. The <strong>Internet</strong> can empower violentradicals as well as peaceful reformers. There is noguarantee that support<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom willenhance freedom or lead to greater democracy. Yetit is virtually certa<strong>in</strong> that if <strong>the</strong> United States ceasesits <strong>Internet</strong> freedom-related activities, <strong>the</strong> balanceof onl<strong>in</strong>e power would shift toward autocraciesseek<strong>in</strong>g to restrict <strong>the</strong>ir populations’ freedom. Thisalone should compel American officials to take<strong>Internet</strong> freedom seriously.A Brief History of <strong>the</strong> U.S. Government’s<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong> EffortsThe U.S. government started pursu<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>Internet</strong>freedom agenda dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> second term of <strong>the</strong>George W. Bush adm<strong>in</strong>istration. Congress beganscrut<strong>in</strong>iz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom issues <strong>in</strong> 2005,focus<strong>in</strong>g particularly on <strong>the</strong> private sector. Reportsthat a local Yahoo affiliate gave <strong>the</strong> email recordsof a journalist to Ch<strong>in</strong>ese authorities, which ledto his 10-year prison sentence, prompted congressionalhear<strong>in</strong>gs that also <strong>in</strong>cluded Microsoft andGoogle. 14 The same year, Congressman ChrisSmith, R-N.J., <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>the</strong> first version of hisGlobal <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong> Act, which would prohibitexport<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> hardware and software torepressive regimes. 15 In 2008, representatives fromCisco Systems, Inc. were asked to appear before<strong>the</strong> Senate Judiciary Committee to determ<strong>in</strong>e if<strong>the</strong> company know<strong>in</strong>gly sold routers to Ch<strong>in</strong>a for<strong>the</strong> purpose of controll<strong>in</strong>g political dissent andstreng<strong>the</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> state’s Great Firewall. 16 TheYahoo <strong>in</strong>cident, toge<strong>the</strong>r with Cisco’s sales andGoogle’s agreement to censor its search results <strong>in</strong>Ch<strong>in</strong>a, generated a larger discussion on CapitolHill about whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> government should prohibitAmerican technology companies from respond<strong>in</strong>gto politically motivated <strong>in</strong>formation requestsor sell<strong>in</strong>g technology that could help governmentscommit human rights violations. After <strong>the</strong> socalledTwitter revolution <strong>in</strong> Iran <strong>in</strong> 2009, Congresspassed <strong>the</strong> Victims of Iranian Censorship (VOICE)Act, which authorized (but did not appropriate) 55million dollars for State Department programs thatwould help <strong>the</strong> Iranian people overcome electroniccensorship and digital oppression. 17The executive branch has also been <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>glyactive. In February 2006, <strong>the</strong>n-Secretary of StateCondoleezza Rice established <strong>the</strong> Global <strong>Internet</strong><strong>Freedom</strong> Task Force (GIFT) as a way to coord<strong>in</strong>ateState Department efforts to promote <strong>Internet</strong>freedom and respond to <strong>Internet</strong> censorship. 18Soon <strong>the</strong>reafter, <strong>the</strong>n-Under Secretary of State for| 11

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>12 |Democracy and Global Affairs Paula Dobrianskyannounced that <strong>the</strong> State Department would henceforth<strong>in</strong>clude a country-level assessment of <strong>Internet</strong>freedom <strong>in</strong> its annual human rights reports.Like its predecessor, <strong>the</strong> Obama adm<strong>in</strong>istration’s<strong>Internet</strong> freedom agenda goes well beyond fund<strong>in</strong>gfirewall-evad<strong>in</strong>g technology. The State Departmenthas bolstered its capacity to use its diplomatic,economic and technological resources to promotea free <strong>Internet</strong>. Cl<strong>in</strong>ton has established a team ofexperts, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a senior advisor for <strong>in</strong>novation,to develop creative ways to blend technology withtraditional diplomatic and development efforts.In addition, <strong>the</strong> State Department re-launched its<strong>Internet</strong> freedom task force <strong>in</strong> 2010, rebrand<strong>in</strong>git <strong>the</strong> “Net<strong>Freedom</strong>” Taskforce, and established aCoord<strong>in</strong>ator for Cyber Issues <strong>in</strong> early 2011. TheWhite House established a deputy chief technologyofficer for <strong>Internet</strong> policy with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Office ofScience and Technology <strong>Policy</strong> (OSTP) to coord<strong>in</strong>ategovernment-wide <strong>Internet</strong> and technologypolicy, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g issues related to cyber securityand <strong>Internet</strong> freedom.Cl<strong>in</strong>ton has led efforts to promote <strong>Internet</strong> freedom<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Obama adm<strong>in</strong>istration. Evok<strong>in</strong>g PresidentFrankl<strong>in</strong> Delano Roosevelt’s 1941 Four <strong>Freedom</strong>sspeech, <strong>in</strong> 2010 Cl<strong>in</strong>ton added a fifth, <strong>the</strong> “freedomto connect – <strong>the</strong> idea that governments should notprevent people from connect<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, towebsites or to each o<strong>the</strong>r.” 19 In a second speech ayear later, she pledged America’s “global commitmentto <strong>Internet</strong> freedom, to protect human rightsonl<strong>in</strong>e as we do offl<strong>in</strong>e,” <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> freedoms ofexpression, assembly and association. 20These speeches represent <strong>the</strong> clearest and mostcomplete articulation of <strong>the</strong> U.S. government’s<strong>Internet</strong> freedom strategy, but questions rema<strong>in</strong>.For example, does <strong>the</strong> government aim to promote<strong>the</strong> onl<strong>in</strong>e freedoms of expression, assemblyand association as <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic goods, regardlessof whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ir exercise engenders democraticchange offl<strong>in</strong>e? Or does <strong>the</strong> U.S. governmentbelieve that, on balance, a freer <strong>Internet</strong> willpromote democratic political change? The adm<strong>in</strong>istrationstill lacks a clear message for precisely whyit is undertak<strong>in</strong>g efforts to promote onl<strong>in</strong>e freedom<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> first place, which has produced confusionabout its overall approach to <strong>Internet</strong> freedom.Craft<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> MessageIn her 2011 speech, Cl<strong>in</strong>ton said, “There is a debatecurrently under way <strong>in</strong> some circles about whe<strong>the</strong>r<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> is a force for liberation or repression.But I th<strong>in</strong>k that debate is largely beside <strong>the</strong> po<strong>in</strong>t.” 21In fact, that is <strong>the</strong> key po<strong>in</strong>t – if <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> is aforce for repression, why should <strong>the</strong> United Statessupport its freer use?Adm<strong>in</strong>istration officials emphasize that <strong>the</strong>irpolicies support freedom of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, notfreedom via <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>; <strong>the</strong>se policies are notpart of a broader democracy-promotion strategy.In her 45-m<strong>in</strong>ute speech, Cl<strong>in</strong>ton used <strong>the</strong>term “democracy” just once, when defend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>adm<strong>in</strong>istration’s position on WikiLeaks. Instead,she said that <strong>the</strong> United States supports a free<strong>Internet</strong> because it helps build “strong” and “prosperous”states. She did not say that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>helps build freer or more democratic states. 22Yet that is a key reason why <strong>the</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>istrationsupports <strong>Internet</strong> freedom. It is <strong>the</strong> central motivationbeh<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong> State Department’s tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g andtechnology programs, which are aimed at onl<strong>in</strong>eactivists, dissidents and democracy-related NGOs.The U.S. government should clearly state why itpromotes <strong>Internet</strong> freedom: Do<strong>in</strong>g so accords withAmerica’s longstand<strong>in</strong>g tradition of promot<strong>in</strong>ghuman rights, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g freedoms of expression,association and assembly, and <strong>the</strong> United Statesis bett<strong>in</strong>g that access to an open <strong>Internet</strong> canfoster elements of democracy <strong>in</strong> autocratic states.Officials can acknowledge <strong>the</strong> potential downsides,but <strong>the</strong>y need not shy from publicly acknowledg<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> U.S. <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> democratization and <strong>the</strong>

hope that promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom can assistthose who are press<strong>in</strong>g for liberal change abroad.The government should not discredit dissidentsby suggest<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>y are an arm of U.S. foreignpolicy, but refra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g entirely from mention<strong>in</strong>gdemocracy <strong>in</strong> connection with <strong>Internet</strong> freedomrisks underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g domestic support for its policies– <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g on Capitol Hill. And <strong>the</strong> current rhetoricalambivalence belies <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly robust– <strong>in</strong>deed, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly impressive – U.S. efforts topromote <strong>Internet</strong> freedom.At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong> United States shouldcounter <strong>the</strong> view that <strong>Internet</strong> freedom is merelyan American project cooked up <strong>in</strong> Wash<strong>in</strong>gton,ra<strong>the</strong>r than a notion rooted <strong>in</strong> universal humanrights. The United States promotes <strong>Internet</strong>freedom more actively than any o<strong>the</strong>r country,and is one of <strong>the</strong> only countries that activelyfunds circumvention technologies. It leads <strong>in</strong>promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternational norms and has made agreater effort than most to <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>Internet</strong>freedom <strong>in</strong>to its broader foreign policy. This hasprovoked concerns that American advocacy willta<strong>in</strong>t <strong>the</strong> efforts of local activists. For example,Sami ben Gharbia, a prom<strong>in</strong>ent Ne<strong>the</strong>rlandsbasedTunisian blogger, has said, “Many peopleoutside of <strong>the</strong> U.S., not only <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Arab world,have a strong feel<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>mantra emitt<strong>in</strong>g from Wash<strong>in</strong>gton D.C. is just acover for strategic geopolitical agendas” and thatthis could threaten activists who accept supportand fund<strong>in</strong>g. 23 Autocratic governments rout<strong>in</strong>elydenounce <strong>Internet</strong> freedom-related activities asimpos<strong>in</strong>g American values, and some technologycompanies and foundations have shied awayfrom support<strong>in</strong>g circumvention and anonymitytechnologies because of <strong>the</strong>ir perceived tie to U.S.foreign policy.effort. Despite reservations from some, more than5,000 foreign activists and o<strong>the</strong>rs have accepted<strong>Internet</strong>-related tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g funded by <strong>the</strong> StateDepartment, and many more employ U.S. government-fundedtechnology. 24 Many governmentshave not yet formulated policies <strong>in</strong> this area, butsome are express<strong>in</strong>g grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> do<strong>in</strong>g so,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g several European countries and <strong>the</strong> EU.To <strong>the</strong> extent that foreign governments advocatefor <strong>Internet</strong> freedom and foreign corporations jo<strong>in</strong>such efforts as <strong>the</strong> GNI and <strong>in</strong>ternational organizationspromote new norms, <strong>the</strong> United States willbe able to make a stronger argument that <strong>Internet</strong>freedom is truly a global effort.The response to such concerns should not be toavoid any suggestion that <strong>Internet</strong> freedom isrelated to American support of democracy andhuman rights, but ra<strong>the</strong>r to <strong>in</strong>ternationalize <strong>the</strong>| 13

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>14 |III. <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>and Political ChangeThe <strong>Internet</strong>’s potential as a tool for politicalchange captivated top foreign policy officials<strong>in</strong> 2009 dur<strong>in</strong>g what was quickly dubbed Iran’sTwitter Revolution. The new awareness grew asprotestors used <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> and text messages tospread <strong>in</strong>formation and coord<strong>in</strong>ate efforts, andwas crystallized by <strong>the</strong> viral movement of a videodepict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> brutal slay<strong>in</strong>g of a young Iranianstudent, Neda Agha-Soltan. The video, whichwas captured on a mobile phone and uploadedto YouTube, traveled across <strong>the</strong> Web and ontolocal and satellite television, prompt<strong>in</strong>g Obamato express his outrage at <strong>the</strong> kill<strong>in</strong>g. When <strong>the</strong>president of <strong>the</strong> United States uses a White Housepress conference to address material uploaded toYouTube, someth<strong>in</strong>g fundamental has changed <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> nature of modern communications.The focus on <strong>Internet</strong> freedom grew as <strong>the</strong> ArabSpr<strong>in</strong>g ga<strong>the</strong>red momentum a year and a half later.The wave of revolts across <strong>the</strong> Arab world, beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> Tunisia, <strong>the</strong>n sweep<strong>in</strong>g across Egypt and<strong>in</strong>to Libya, Bahra<strong>in</strong>, Yemen, Syria and elsewherewere fueled <strong>in</strong> part by activists us<strong>in</strong>g tools such asFacebook, Twitter, SMS (text messag<strong>in</strong>g) and o<strong>the</strong>rplatforms. Several regimes took draconian steps tostop onl<strong>in</strong>e organiz<strong>in</strong>g and communication. Thesense grew that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> mattered, but just howit mattered was not totally clear.In a sense, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> represents just <strong>the</strong> latestpart of a story that has unfolded for centuries.Communication technologies have played significantroles <strong>in</strong> political movements s<strong>in</strong>ce antiquity,from <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g press that empowered <strong>the</strong>Reformation, cassette tapes distributed by Iranianrevolutionaries <strong>in</strong> 1979, to fax mach<strong>in</strong>es used byPoland’s Solidarity movement and satellite televisiontoday. But <strong>the</strong> global nature of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>,its very low barrier to entry, its speed and <strong>the</strong>degree to which it empowers <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual allmake it qualitatively different from earlier technologies.The <strong>Internet</strong> itself has become <strong>the</strong> focusof attention by dictators, democracy activists andobservers around <strong>the</strong> world.Does <strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong> Lead to Democracy?The United States promotes <strong>Internet</strong> freedombecause Americans believe <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> freedom ofexpression, <strong>in</strong> any medium. The country alsopromotes it because American leaders have betthat, on balance, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased availability of new,unfettered communications technologies abets <strong>the</strong>spread of democracy. But does it?Here we use <strong>the</strong> term “democracy” to mean a politicalsystem that is transparent and accountable to<strong>the</strong> public through free and fair elections; <strong>in</strong>cludesactive political participation by <strong>the</strong> citizenry;protects human rights; and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>s a rule oflaw that is fair to all citizens. 25 This is obviously anideal, and democratic systems exhibit many variations,but this def<strong>in</strong>ition offers a useful standardfor measur<strong>in</strong>g potential progress.Experts rema<strong>in</strong> deeply divided, as shown <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>text box on <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g page, as to whe<strong>the</strong>runbridled access to <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> can help transformauthoritarian regimes over time and br<strong>in</strong>g greaterfreedom to once-closed societies. Most attemptsto assess its impact rely on case studies, anecdotesor <strong>the</strong>ory. The novelty of <strong>the</strong> phenomenon and <strong>the</strong>few and widely vary<strong>in</strong>g data po<strong>in</strong>ts pose notableanalytical challenges, and assessments requirea certa<strong>in</strong> amount of subjective <strong>in</strong>terpretation.Facebook clearly played a major role <strong>in</strong> build<strong>in</strong>g anopposition to <strong>the</strong> Hosni Mubarak regime <strong>in</strong> Egyptand <strong>in</strong> organiz<strong>in</strong>g protests. But after <strong>the</strong> governmentshut off <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>, protests became bigger,not smaller. So did this demonstrate <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>’slimited role as a tool of agitation? Or did <strong>the</strong>shutoff of cherished onl<strong>in</strong>e tools itself spur enragedcitizens to demonstrate <strong>in</strong>stead of stay<strong>in</strong>g home(possibly <strong>in</strong> front of a computer)?

Does <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> Promote Democracy?Optimists“The <strong>Internet</strong> is above all <strong>the</strong> most fantastic means ofbreak<strong>in</strong>g down <strong>the</strong> walls that close us off from oneano<strong>the</strong>r. For <strong>the</strong> oppressed peoples of <strong>the</strong> world,<strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> provides power beyond <strong>the</strong>ir wildesthopes.” 26Bernard KouchnerFormer French <strong>Foreign</strong> M<strong>in</strong>ister“It does make a difference when people <strong>in</strong>side closedregimes get access to <strong>in</strong>formation – which is whydictatorships make such efforts to block comprehensive<strong>Internet</strong> access … [promot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Internet</strong> freedom]would be a cheap and effective way of stand<strong>in</strong>g withIranians while chipp<strong>in</strong>g away at <strong>the</strong> 21st-century wallsof dictatorship.” 27Nicholas KristofThe New York Times columnist“The <strong>Internet</strong> is possibly one of <strong>the</strong> greatest tools fordemocratization and <strong>in</strong>dividual freedom that we’veever seen.” 28Condoleezza RiceFormer Secretary of State“Without Twitter, <strong>the</strong> people of Iran would not havefelt empowered and confident to stand up for freedomand democracy.” 29Mark PfeifleFormer Deputy National Security Advisor“If you want to liberate a society, just give <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong><strong>Internet</strong>.” 30Wael GhonimEgyptian Google Executiveand democracy activistSkeptics“The idea that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> favors <strong>the</strong> oppressedra<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>the</strong> oppressor is marred by what I callcyber-utopianism: a naïve belief <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> emancipatorynature of onl<strong>in</strong>e communication that rests on a stubbornrefusal to admit its downside.” 31Evgeny MorozovAuthor of The Net Delusion“The platforms of social media are built around weakties … weak ties seldom lead to high-risk activism.” 32Malcolm GladwellThe New Yorker staff writer“Democracy isn’t just a tweet away.” 33Jeffrey Gedm<strong>in</strong>Former President of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty“It is time to get Twitter’s role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> events <strong>in</strong> Iranright. Simply put: There was no Twitter Revolution<strong>in</strong>side Iran.” 34Golnaz EsfandiariSenior Correspondent for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty“Techno-optimists appear to ignore <strong>the</strong> fact that<strong>the</strong>se tools are value neutral; <strong>the</strong>re is noth<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>herentlypro-democratic about <strong>the</strong>m. To use <strong>the</strong>m is toexercise a form of freedom, but it is not necessarily afreedom that promotes <strong>the</strong> freedom of o<strong>the</strong>rs.” 35Ian BremmerPresident of <strong>the</strong> Eurasia GroupIt has become axiomatic to say that <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> doesnot itself create democracies or overthrow regimes;people do. This is obviously true, but if new communicationstools do matter – and <strong>the</strong>re appears to be atleast nascent evidence that <strong>the</strong>y do – <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong>y can playa role <strong>in</strong> several dist<strong>in</strong>ct ways. An important reportissued by <strong>the</strong> United States Institute of Peace (USIP)presented a useful framework for exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g how newcommunications technologies might affect politicalaction. The paper identifies five dist<strong>in</strong>ct mechanismsthrough which <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> might promote (or be usedby regimes to block) democratic progress. 36 Here wedeepen <strong>the</strong> analysis of <strong>the</strong>se mechanisms and add twoadditional factors that affect <strong>the</strong>m.| 15

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>16 |The <strong>Internet</strong> may affect <strong>in</strong>dividuals, by alter<strong>in</strong>g orre<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir political attitudes, mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mmore attuned to political events, and enabl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mto participate <strong>in</strong> politics to a greater degree than<strong>the</strong>y could o<strong>the</strong>rwise. This does not automaticallytranslate <strong>in</strong>to a more activist population; as <strong>the</strong>USIP study notes, it could actually make citizensmore passive by divert<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir attention away fromoffl<strong>in</strong>e political activism and toward less significantonl<strong>in</strong>e activity. 37 Some have called this “slacktivism,”exemplified by <strong>the</strong> millions of <strong>in</strong>dividuals whosigned onl<strong>in</strong>e petitions to end genocide <strong>in</strong> Darfurbut who took no fur<strong>the</strong>r action. 38 At <strong>the</strong> same time,<strong>in</strong>dividuals freely express<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mselves on <strong>the</strong><strong>Internet</strong> are exercis<strong>in</strong>g a basic democratic right. Asdemocracy scholar Larry Diamond po<strong>in</strong>ts out, used<strong>in</strong> this way, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> can help “widen <strong>the</strong> publicsphere, creat<strong>in</strong>g a more pluralistic and autonomousarena of news, commentary and <strong>in</strong>formation.” 39It can also serve as an <strong>in</strong>strument through which<strong>in</strong>dividuals can push for transparency and governmentaccountability, both of which are hallmarks ofmature democracies. 40New media might also affect <strong>in</strong>tergroup relations,by generat<strong>in</strong>g new connections among <strong>in</strong>dividuals,spread<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation and br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g toge<strong>the</strong>rpeople and groups. (Some have worried about <strong>the</strong>opposite effect – <strong>the</strong> tendency of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> topolarize <strong>in</strong>dividuals and groups around particularideological tendencies.) 41 This may occur notonly with<strong>in</strong> countries, but also among <strong>the</strong>m; <strong>the</strong>protests <strong>in</strong> Tunisia sparked a clear rise <strong>in</strong> politicalconsciousness and activism across <strong>the</strong> Arab world– much of it facilitated by <strong>Internet</strong>-based communicationsand satellite television. 42 It may also takeplace over a long period of time; Clay Shirky, anexpert at New York University, argues that a “densify<strong>in</strong>gof <strong>the</strong> public sphere” may need to occurbefore an upris<strong>in</strong>g turns <strong>in</strong>to a revolution. 43New communications technologies could alsoaffect collective action, by help<strong>in</strong>g change op<strong>in</strong>ionand mak<strong>in</strong>g it easier for <strong>in</strong>dividuals and groupsto organize protests <strong>in</strong> repressive countries.Unconnected <strong>in</strong>dividuals dissatisfied with <strong>the</strong>prevail<strong>in</strong>g politics may realize that o<strong>the</strong>rs share<strong>the</strong>ir views, which might form <strong>the</strong> basis for collectiveaction. 44 Relatively small groups, elites oro<strong>the</strong>r motivated dissidents might use <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>to communicate or organize protests. Even if <strong>the</strong>number of committed onl<strong>in</strong>e activists is small, <strong>the</strong>ymight never<strong>the</strong>less dissem<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>the</strong>general population or <strong>in</strong>spire more widespreadprotests. 45 Aga<strong>in</strong>, it is important to dist<strong>in</strong>guishsuch action from group “slacktivism;” as <strong>the</strong>successful protests <strong>in</strong> Egypt showed, <strong>the</strong> regimeonly began to teeter when thousands of citizensphysically occupied Tahrir Square. Though <strong>in</strong>itialprotests may have been organized via Facebook,<strong>the</strong> Mubarak government would still be <strong>in</strong> power if<strong>the</strong> protests had been conf<strong>in</strong>ed only to cyberspace.These new technologies clearly affect regimepolicies as well. Governments have employed ahuge array of techniques aimed at controll<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong><strong>Internet</strong> and ensur<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong>ir political opponentscannot use it freely. This goes well beyondcensorship, which garners <strong>the</strong> bulk of popularattention. Autocracies also regularly monitor dissidentcommunications; mobilize regime defenders;spread propaganda and false <strong>in</strong>formation designedto disrupt protests and outside groups; <strong>in</strong>filtratesocial movements; and disable dissident websites,communications tools and databases. These ando<strong>the</strong>r practices can also <strong>in</strong>duce self-censorship ando<strong>the</strong>r forms of self-restra<strong>in</strong>t by publishers, activists,onl<strong>in</strong>e commentators and opposition politicians.Autocrats can also turn dissidents’ use of <strong>the</strong><strong>Internet</strong> aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong>m. In Iran, for example, usersof social media – which l<strong>in</strong>ked <strong>the</strong>ir accounts tothose of o<strong>the</strong>r protestors – <strong>in</strong>advertently createda virtual catalogue of political opponents thatenabled <strong>the</strong> government to identify and persecute<strong>in</strong>dividuals. The regime established a website thatpublished photos of protestors and used crowdsourc<strong>in</strong>g to identify <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals’ names. 46

Similarly, <strong>the</strong> Revolutionary Guard reportedlysent <strong>in</strong>timidat<strong>in</strong>g messages to those who postedpro-opposition messages and forced some citizensenter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> country to open <strong>the</strong>ir Facebookaccounts upon arrival. 47 In <strong>the</strong> midst of <strong>the</strong>Arab protests, Syria allowed its citizens to accessFacebook and YouTube for <strong>the</strong> first time <strong>in</strong> threeyears. Some human rights activists suspected that<strong>the</strong> government made <strong>the</strong> change precisely <strong>in</strong> orderto monitor people and activities on <strong>the</strong>se sites. 48Similarly, shortly after <strong>the</strong> Egyptian governmentlifted its <strong>Internet</strong> blackout <strong>in</strong> early 2011, pro-Mubaraksupporters disrupted planned demonstrationsby post<strong>in</strong>g messages on Facebook and Twittersay<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> protests had been canceled. 49 Thegovernment reportedly sent Facebook messages tocitizens urg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m not to attend protests becausedo<strong>in</strong>g so would harm <strong>the</strong> Egyptian economy. 50 In<strong>the</strong> same ve<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese government employsan estimated 250,000 “50 Cent Party” memberswho are paid a small sum each time <strong>the</strong>y posta pro-government message onl<strong>in</strong>e. 51 And afteran anonymous post on <strong>the</strong> U.S.-based Ch<strong>in</strong>eselanguage website Boxun.com called on activiststo stage Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s own “Jasm<strong>in</strong>e Revolution,” nodemonstrators turned up at <strong>the</strong> rally po<strong>in</strong>t – but itwas flooded with security teams and pla<strong>in</strong>clo<strong>the</strong>sofficers. 52 Some speculated that Ch<strong>in</strong>ese officials<strong>the</strong>mselves may have authored <strong>the</strong> anonymouspost<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> an effort to draw out political dissidents.53 While no evidence has emerged to support<strong>the</strong> claim, it is not hard to imag<strong>in</strong>e such an attempttak<strong>in</strong>g place <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future.Autocracies are engaged <strong>in</strong> “offl<strong>in</strong>e” attempts torepress <strong>Internet</strong> use, as well. Saudi Arabia, forexample, has not only blocked websites but alsoplaced hidden cameras <strong>in</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> cafes aimedat monitor<strong>in</strong>g user behavior and required cafeowners to give <strong>the</strong>ir customer lists to governmentofficials. 54 Ch<strong>in</strong>a requires users to register <strong>the</strong>iridentification upon entry to a cybercafe. 55 AndLibyan officials simply demanded that refugeesflee<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> recent fight<strong>in</strong>g turn over <strong>the</strong>ir cellphonesor SIM cards at border checkpo<strong>in</strong>ts. 56Beyond <strong>the</strong>se effects, new media can affect externalattention, by transmitt<strong>in</strong>g images and <strong>in</strong>formationto <strong>the</strong> outside world, beyond <strong>the</strong> control ofgovernment-run media and regime censorship andsp<strong>in</strong>. Such attention can mobilize sympathy forprotestors or hostility toward repressive regimes, 57as occurred when <strong>the</strong> video of Neda Agha-Soltanmoved from YouTube to ma<strong>in</strong>stream media.<strong>Digital</strong> videos and <strong>in</strong>formation may also have arebound effect; <strong>in</strong>formation transmitted out ofEgypt and Libya by social network<strong>in</strong>g and videohost<strong>in</strong>gsites dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> protests <strong>in</strong> those countriesmade its way back <strong>in</strong> via widely watched satellitebroadcasts. This effect could be particularly pronounced<strong>in</strong> countries like Yemen, where <strong>Internet</strong>penetration is low but Al Jazeera is widely viewed.Similarly, pr<strong>in</strong>t journalists have found sources andstories through social media and have used <strong>the</strong>same media to push <strong>the</strong>ir articles out to <strong>the</strong> world.In addition to <strong>the</strong> five mechanisms laid out byUSIP and noted above, we observe two additionalfactors that affect <strong>the</strong>m <strong>in</strong> various ways.The economic impact of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> might affect<strong>the</strong> degree of democratization <strong>in</strong> a country. The<strong>Internet</strong> has <strong>in</strong>creased labor productivity and correspond<strong>in</strong>geconomic growth, which may help middleclasses emerge <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. 58 Becausenew middle classes tend to agitate for democraticrights, new technologies could <strong>in</strong>directly promotedemocratization. In 2011, Cl<strong>in</strong>ton referenced arelated dynamic, <strong>the</strong> “dictator’s dilemma,” stat<strong>in</strong>gthat autocrats “will have to choose between lett<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> walls fall or pay<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> price to keep <strong>the</strong>mstand<strong>in</strong>g … by resort<strong>in</strong>g to greater oppression andendur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> escalat<strong>in</strong>g opportunity cost of miss<strong>in</strong>gout on <strong>the</strong> ideas that have been blocked and peoplewho have been disappeared.” 59 In o<strong>the</strong>r words, anautocrat can ei<strong>the</strong>r repress <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> or enjoy itsfull economic benefits, but not both.| 17

J U N E 2 0 1 1<strong>Internet</strong> <strong>Freedom</strong>A <strong>Foreign</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Imperative</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Digital</strong> <strong>Age</strong>18 |Whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> “dictator’s dilemma” actually existsrema<strong>in</strong>s unknown. There are certa<strong>in</strong>ly clear<strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong>stances where <strong>Internet</strong> repressionhas damaged a nation’s economy; Experts from<strong>the</strong> Organisation for Economic Co-operation andDevelopment (OECD) have estimated that Egypt’sfive-day <strong>Internet</strong> shutdown cost <strong>the</strong> country at least90 million dollars, a figure that does not <strong>in</strong>cludee-commerce, tourism or o<strong>the</strong>r bus<strong>in</strong>esses that relyon <strong>Internet</strong> connectivity. 60 But Ch<strong>in</strong>a seems to providea powerful counterexample s<strong>in</strong>ce it severelyrepresses <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong> while enjoy<strong>in</strong>g extraord<strong>in</strong>arilyhigh rates of susta<strong>in</strong>ed economic growth.Indeed, Ch<strong>in</strong>a appears to have used its restrictive<strong>Internet</strong> practices to squeeze out <strong>in</strong>ternationalcompetition and generate conditions where onlydomestic companies – ones that adhere to <strong>the</strong>government’s str<strong>in</strong>gent censorship and monitor<strong>in</strong>gpractices – can thrive. Ch<strong>in</strong>a’s largest domesticsearch eng<strong>in</strong>e, Baidu, exercises strict controls oncontent but has thrived s<strong>in</strong>ce Google pulled outof Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> January 2010. Ch<strong>in</strong>a may be an outlier;<strong>the</strong> massive f<strong>in</strong>ancial and human resourcesit devotes to onl<strong>in</strong>e control may not be replicableelsewhere. O<strong>the</strong>r countries may be left with blunterforms of repression that degrade both <strong>the</strong> <strong>Internet</strong>’seconomic and political effects.In addition to <strong>the</strong> political and economic effectsdescribed above, new technologies can accelerateeach of <strong>the</strong>m. Google’s Eric Schmidt and JaredCohen have argued that faster computer powercomb<strong>in</strong>ed with <strong>the</strong> “many to many” geometry ofsocial media empowers <strong>in</strong>dividuals and groupsat <strong>the</strong> expense of governments and that this, <strong>in</strong>turn, <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>the</strong> rate of change. 61 Dissidents canidentify one ano<strong>the</strong>r, share <strong>in</strong>formation, organizeand connect with leaders and with external actors,all easier and faster than ever before. 62 Indeed, onehallmark of <strong>the</strong> 2011 Arab Spr<strong>in</strong>g was <strong>the</strong> astonish<strong>in</strong>grate of change as popular protests threatenedor toppled governments that had been <strong>in</strong> power fordecades <strong>in</strong> a matter of weeks. 63Aga<strong>in</strong>, <strong>the</strong> local political context is critical. Themedium may be global, but whe<strong>the</strong>r and how itenables <strong>in</strong>dividuals to foster democratic changelargely depends on a wide array of local variables,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g opposition leadership, <strong>the</strong> existence ofcivil society <strong>in</strong>stitutions, <strong>the</strong> will<strong>in</strong>gness of <strong>the</strong>regime to crack down on dissident activity, and soforth. In Tunisia and Egypt for example, tens ofthousands of protestors responded to protest eventpages on Facebook by tak<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> streets. Yet <strong>in</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r Arab states, a call on Facebook for a “dayof rage” did not have <strong>the</strong> same pronounced <strong>in</strong>fluence.The degree of openness <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> local politicalsystem, <strong>the</strong> discontent among <strong>the</strong> population,<strong>the</strong> will<strong>in</strong>gness of <strong>the</strong> government to use coercivemeans to stop democratic activism, <strong>the</strong> role ofm<strong>in</strong>orities and o<strong>the</strong>r local factors all matter greatly.Experts from <strong>the</strong> Organisationfor Economic Co-operationand Development haveestimated that Egypt’s fiveday<strong>Internet</strong> shutdown cost<strong>the</strong> country at least 90 milliondollars, a figure that does not<strong>in</strong>clude e-commerce, tourismor o<strong>the</strong>r bus<strong>in</strong>esses that rely on<strong>Internet</strong> connectivity.The <strong>Internet</strong> does not automatically promotedemocratization; Iran’s Twitter revolution ledto no reforms while Egypt’s Facebook revolutiontoppled <strong>the</strong> Mubarak regime. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,<strong>the</strong> technology itself is agnostic; <strong>the</strong> same onl<strong>in</strong>e