PDF COPY - Manuel berberian

PDF COPY - Manuel berberian

PDF COPY - Manuel berberian

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

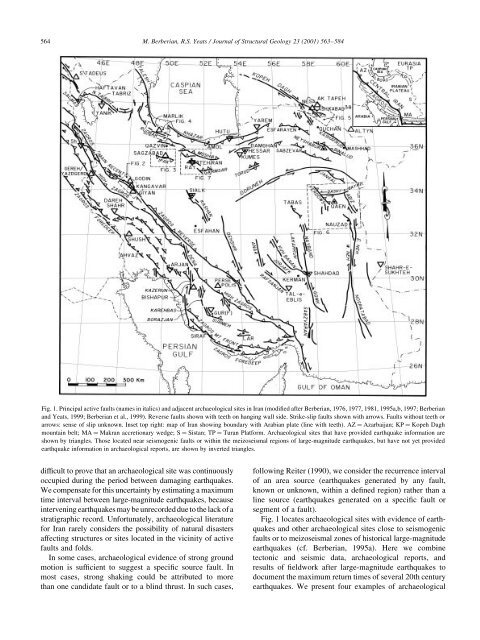

564M. Berberian, R.S. Yeats / Journal of Structural Geology 23 (2001) 563±584Fig. 1. Principal active faults (names in italics) and adjacent archaeological sites in Iran (modi®ed after Berberian, 1976, 1977, 1981, 1995a,b, 1997; Berberianand Yeats, 1999; Berberian et al., 1999). Reverse faults shown with teeth on hanging wall side. Strike-slip faults shown with arrows. Faults without teeth orarrows: sense of slip unknown. Inset top right: map of Iran showing boundary with Arabian plate (line with teeth). AZ ˆ Azarbaijan; KP ˆ Kopeh Daghmountain belt; MA ˆ Makran accretionary wedge; S ˆ Sistan; TP ˆ Turan Platform. Archaeological sites that have provided earthquake information areshown by triangles. Those located near seismogenic faults or within the meizoseismal regions of large-magnitude earthquakes, but have not yet providedearthquake information in archaeological reports, are shown by inverted triangles.dif®cult to prove that an archaeological site was continuouslyoccupied during the period between damaging earthquakes.We compensate for this uncertainty by estimating a maximumtime interval between large-magnitude earthquakes, becauseintervening earthquakes may be unrecorded due to the lack of astratigraphic record. Unfortunately, archaeological literaturefor Iran rarely considers the possibility of natural disastersaffecting structures or sites located in the vicinity of activefaults and folds.In some cases, archaeological evidence of strong groundmotion is suf®cient to suggest a speci®c source fault. Inmost cases, strong shaking could be attributed to morethan one candidate fault or to a blind thrust. In such cases,following Reiter (1990), we consider the recurrence intervalof an area source (earthquakes generated by any fault,known or unknown, within a de®ned region) rather than aline source (earthquakes generated on a speci®c fault orsegment of a fault).Fig. 1 locates archaeological sites with evidence of earthquakesand other archaeological sites close to seismogenicfaults or to meizoseismal zones of historical large-magnitudeearthquakes (cf. Berberian, 1995a). Here we combinetectonic and seismic data, archaeological reports, andresults of ®eldwork after large-magnitude earthquakes todocument the maximum return times of several 20th centuryearthquakes. We present four examples of archaeological