2011 Culturally Modified Landscapes from Past to Present

2011 Culturally Modified Landscapes from Past to Present

2011 Culturally Modified Landscapes from Past to Present

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

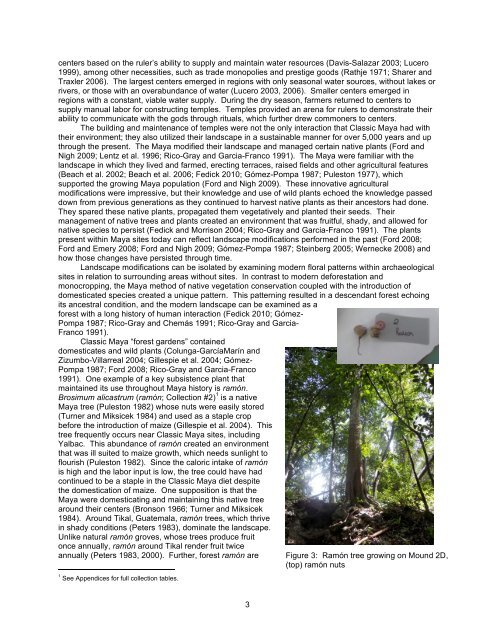

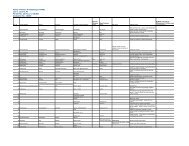

centers based on the ruler’s ability <strong>to</strong> supply and maintain water resources (Davis-Salazar 2003; Lucero1999), among other necessities, such as trade monopolies and prestige goods (Rathje 1971; Sharer andTraxler 2006). The largest centers emerged in regions with only seasonal water sources, without lakes orrivers, or those with an overabundance of water (Lucero 2003, 2006). Smaller centers emerged inregions with a constant, viable water supply. During the dry season, farmers returned <strong>to</strong> centers <strong>to</strong>supply manual labor for constructing temples. Temples provided an arena for rulers <strong>to</strong> demonstrate theirability <strong>to</strong> communicate with the gods through rituals, which further drew commoners <strong>to</strong> centers.The building and maintenance of temples were not the only interaction that Classic Maya had withtheir environment; they also utilized their landscape in a sustainable manner for over 5,000 years and upthrough the present. The Maya modified their landscape and managed certain native plants (Ford andNigh 2009; Lentz et al. 1996; Rico-Gray and Garcia-Franco 1991). The Maya were familiar with thelandscape in which they lived and farmed, erecting terraces, raised fields and other agricultural features(Beach et al. 2002; Beach et al. 2006; Fedick 2010; Gómez-Pompa 1987; Pules<strong>to</strong>n 1977), whichsupported the growing Maya population (Ford and Nigh 2009). These innovative agriculturalmodifications were impressive, but their knowledge and use of wild plants echoed the knowledge passeddown <strong>from</strong> previous generations as they continued <strong>to</strong> harvest native plants as their ances<strong>to</strong>rs had done.They spared these native plants, propagated them vegetatively and planted their seeds. Theirmanagement of native trees and plants created an environment that was fruitful, shady, and allowed fornative species <strong>to</strong> persist (Fedick and Morrison 2004; Rico-Gray and Garcia-Franco 1991). The plantspresent within Maya sites <strong>to</strong>day can reflect landscape modifications performed in the past (Ford 2008;Ford and Emery 2008; Ford and Nigh 2009; Gómez-Pompa 1987; Steinberg 2005; Wernecke 2008) andhow those changes have persisted through time.Landscape modifications can be isolated by examining modern floral patterns within archaeologicalsites in relation <strong>to</strong> surrounding areas without sites. In contrast <strong>to</strong> modern deforestation andmonocropping, the Maya method of native vegetation conservation coupled with the introduction ofdomesticated species created a unique pattern. This patterning resulted in a descendant forest echoingits ancestral condition, and the modern landscape can be examined as aforest with a long his<strong>to</strong>ry of human interaction (Fedick 2010; Gómez-Pompa 1987; Rico-Gray and Chemás 1991; Rico-Gray and Garcia-Franco 1991).Classic Maya “forest gardens” containeddomesticates and wild plants (Colunga-GarcíaMarín andZizumbo-Villarreal 2004; Gillespie et al. 2004; Gómez-Pompa 1987; Ford 2008; Rico-Gray and Garcia-Franco1991). One example of a key subsistence plant thatmaintained its use throughout Maya his<strong>to</strong>ry is ramón.Brosimum alicastrum (ramón; Collection #2) 1 is a nativeMaya tree (Pules<strong>to</strong>n 1982) whose nuts were easily s<strong>to</strong>red(Turner and Miksicek 1984) and used as a staple cropbefore the introduction of maize (Gillespie et al. 2004). Thistree frequently occurs near Classic Maya sites, includingYalbac. This abundance of ramón created an environmentthat was ill suited <strong>to</strong> maize growth, which needs sunlight <strong>to</strong>flourish (Pules<strong>to</strong>n 1982). Since the caloric intake of ramónis high and the labor input is low, the tree could have hadcontinued <strong>to</strong> be a staple in the Classic Maya diet despitethe domestication of maize. One supposition is that theMaya were domesticating and maintaining this native treearound their centers (Bronson 1966; Turner and Miksicek1984). Around Tikal, Guatemala, ramón trees, which thrivein shady conditions (Peters 1983), dominate the landscape.Unlike natural ramón groves, whose trees produce frui<strong>to</strong>nce annually, ramón around Tikal render fruit twiceannually (Peters 1983, 2000). Further, forest ramón are1See Appendices for full collection tables.Figure 3: Ramón tree growing on Mound 2D,(<strong>to</strong>p) ramón nuts3