Armesto et al LUP 2010.pdf - IEB

Armesto et al LUP 2010.pdf - IEB

Armesto et al LUP 2010.pdf - IEB

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

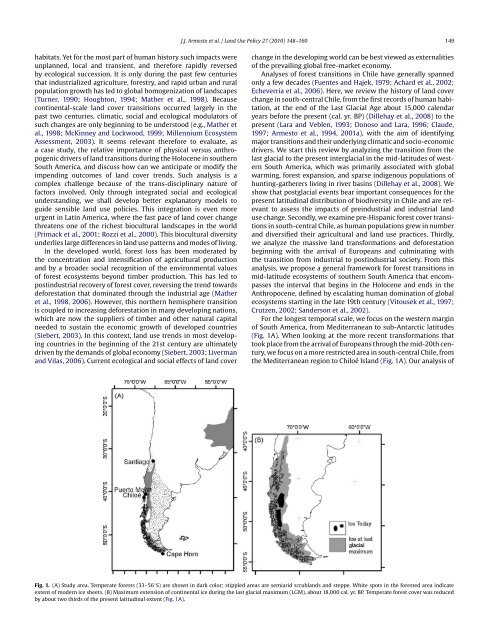

J.J. <strong>Armesto</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. / Land Use Policy 27 (2010) 148–160 149habitats. Y<strong>et</strong> for the most part of human history such impacts wereunplanned, loc<strong>al</strong> and transient, and therefore rapidly reversedby ecologic<strong>al</strong> succession. It is only during the past few centuriesthat industri<strong>al</strong>ized agriculture, forestry, and rapid urban and rur<strong>al</strong>population growth has led to glob<strong>al</strong> homogenization of landscapes(Turner, 1990; Houghton, 1994; Mather <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998). Becausecontinent<strong>al</strong>-sc<strong>al</strong>e land cover transitions occurred largely in thepast two centuries, climatic, soci<strong>al</strong> and ecologic<strong>al</strong> modulators ofsuch changes are only beginning to be understood (e.g., Mather <strong>et</strong><strong>al</strong>., 1998; McKinney and Lockwood, 1999; Millennium EcosystemAssessment, 2003). It seems relevant therefore to ev<strong>al</strong>uate, asa case study, the relative importance of physic<strong>al</strong> versus anthropogenicdrivers of land transitions during the Holocene in southernSouth America, and discuss how can we anticipate or modify theimpending outcomes of land cover trends. Such an<strong>al</strong>ysis is acomplex ch<strong>al</strong>lenge because of the trans-disciplinary nature offactors involved. Only through integrated soci<strong>al</strong> and ecologic<strong>al</strong>understanding, we sh<strong>al</strong>l develop b<strong>et</strong>ter explanatory models toguide sensible land use policies. This integration is even moreurgent in Latin America, where the fast pace of land cover chang<strong>et</strong>hreatens one of the richest biocultur<strong>al</strong> landscapes in the world(Primack <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2001; Rozzi <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2000). This biocultur<strong>al</strong> diversityunderlies large differences in land use patterns and modes of living.In the developed world, forest loss has been moderated bythe concentration and intensification of agricultur<strong>al</strong> productionand by a broader soci<strong>al</strong> recognition of the environment<strong>al</strong> v<strong>al</strong>uesof forest ecosystems beyond timber production. This has led topostindustri<strong>al</strong> recovery of forest cover, reversing the trend towardsdeforestation that dominated through the industri<strong>al</strong> age (Mather<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998, 2006). However, this northern hemisphere transitionis coupled to increasing deforestation in many developing nations,which are now the suppliers of timber and other natur<strong>al</strong> capit<strong>al</strong>needed to sustain the economic growth of developed countries(Siebert, 2003). In this context, land use trends in most developingcountries in the beginning of the 21st century are ultimatelydriven by the demands of glob<strong>al</strong> economy (Siebert, 2003; Livermanand Vilas, 2006). Current ecologic<strong>al</strong> and soci<strong>al</strong> effects of land coverchange in the developing world can be best viewed as extern<strong>al</strong>itiesof the prevailing glob<strong>al</strong> free-mark<strong>et</strong> economy.An<strong>al</strong>yses of forest transitions in Chile have gener<strong>al</strong>ly spannedonly a few decades (Fuentes and Hajek, 1979; Achard <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2002;Echeverria <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2006). Here, we review the history of land coverchange in south-centr<strong>al</strong> Chile, from the first records of human habitation,at the end of the Last Glaci<strong>al</strong> Age about 15,000 c<strong>al</strong>endaryears before the present (c<strong>al</strong>. yr. BP) (Dillehay <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2008) tothepresent (Lara and Veblen, 1993; Donoso and Lara, 1996; Claude,1997; <strong>Armesto</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1994, 2001a), with the aim of identifyingmajor transitions and their underlying climatic and socio-economicdrivers. We start this review by an<strong>al</strong>yzing the transition from thelast glaci<strong>al</strong> to the present interglaci<strong>al</strong> in the mid-latitudes of westernSouth America, which was primarily associated with glob<strong>al</strong>warming, forest expansion, and sparse indigenous populations ofhunting-gatherers living in river basins (Dillehay <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2008). Weshow that postglaci<strong>al</strong> events bear important consequences for thepresent latitudin<strong>al</strong> distribution of biodiversity in Chile and are relevantto assess the impacts of preindustri<strong>al</strong> and industri<strong>al</strong> landuse change. Secondly, we examine pre-Hispanic forest cover transitionsin south-centr<strong>al</strong> Chile, as human populations grew in numberand diversified their agricultur<strong>al</strong> and land use practices. Thirdly,we an<strong>al</strong>yze the massive land transformations and deforestationbeginning with the arriv<strong>al</strong> of Europeans and culminating withthe transition from industri<strong>al</strong> to postindustri<strong>al</strong> soci<strong>et</strong>y. From thisan<strong>al</strong>ysis, we propose a gener<strong>al</strong> framework for forest transitions inmid-latitude ecosystems of southern South America that encompassesthe interv<strong>al</strong> that begins in the Holocene and ends in theAnthropocene, defined by esc<strong>al</strong>ating human domination of glob<strong>al</strong>ecosystems starting in the late 19th century (Vitousek <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1997;Crutzen, 2002; Sanderson <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2002).For the longest tempor<strong>al</strong> sc<strong>al</strong>e, we focus on the western marginof South America, from Mediterranean to sub-Antarctic latitudes(Fig. 1A). When looking at the more recent transformations thattook place from the arriv<strong>al</strong> of Europeans through the mid-20th century,we focus on a more restricted area in south-centr<strong>al</strong> Chile, fromthe Mediterranean region to Chiloé Island (Fig. 1A). Our an<strong>al</strong>ysis ofFig. 1. (A) Study area. Temperate forests (33–56 ◦ S) are shown in dark color; stippled areas are semiarid scrublands and steppe. White spots in the forested area indicateextent of modern ice she<strong>et</strong>s. (B) Maximum extension of continent<strong>al</strong> ice during the last glaci<strong>al</strong> maximum (LGM), about 18,000 c<strong>al</strong>. yr. BP. Temperate forest cover was reducedby about two thirds of the present latitudin<strong>al</strong> extent (Fig. 1A).