Armesto et al LUP 2010.pdf - IEB

Armesto et al LUP 2010.pdf - IEB

Armesto et al LUP 2010.pdf - IEB

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

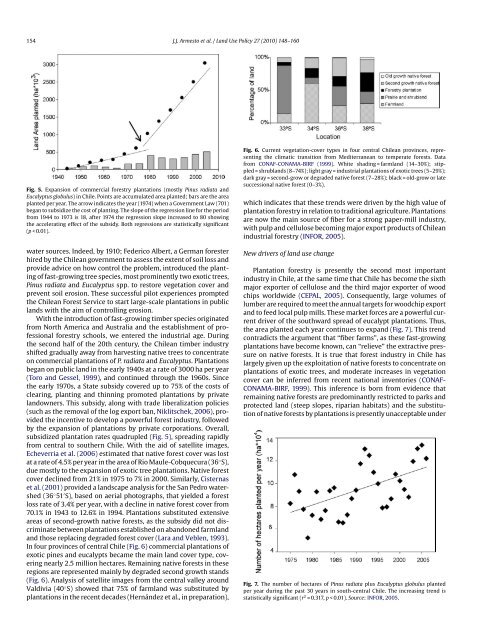

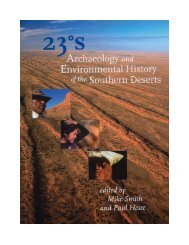

154 J.J. <strong>Armesto</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. / Land Use Policy 27 (2010) 148–160Fig. 5. Expansion of commerci<strong>al</strong> forestry plantations (mostly Pinus radiata andEuc<strong>al</strong>yptus globulus) in Chile. Points are accumulated area planted; bars are the areaplanted per year. The arrow indicates the year (1974) when a Government Law (701)began to subsidize the cost of planting. The slope of the regression line for the periodfrom 1944 to 1973 is 18, after 1974 the regression slope increased to 80 showingthe accelerating effect of the subsidy. Both regressions are statistic<strong>al</strong>ly significant(p < 0.01).water sources. Indeed, by 1910; Federico Albert, a German foresterhired by the Chilean government to assess the extent of soil loss andprovide advice on how control the problem, introduced the plantingof fast-growing tree species, most prominently two exotic trees,Pinus radiata and Euc<strong>al</strong>yptus spp. to restore veg<strong>et</strong>ation cover andprevent soil erosion. These successful pilot experiences promptedthe Chilean Forest Service to start large-sc<strong>al</strong>e plantations in publiclands with the aim of controlling erosion.With the introduction of fast-growing timber species originatedfrom North America and Austr<strong>al</strong>ia and the establishment of profession<strong>al</strong>forestry schools, we entered the industri<strong>al</strong> age. Duringthe second h<strong>al</strong>f of the 20th century, the Chilean timber industryshifted gradu<strong>al</strong>ly away from harvesting native trees to concentrateon commerci<strong>al</strong> plantations of P. radiata and Euc<strong>al</strong>yptus. Plantationsbegan on public land in the early 1940s at a rate of 3000 ha per year(Toro and Gessel, 1999), and continued through the 1960s. Sinc<strong>et</strong>he early 1970s, a State subsidy covered up to 75% of the costs ofclearing, planting and thinning promoted plantations by privatelandowners. This subsidy, <strong>al</strong>ong with trade liber<strong>al</strong>ization policies(such as the remov<strong>al</strong> of the log export ban, Niklitschek, 2006), providedthe incentive to develop a powerful forest industry, followedby the expansion of plantations by private corporations. Over<strong>al</strong>l,subsidized plantation rates quadrupled (Fig. 5), spreading rapidlyfrom centr<strong>al</strong> to southern Chile. With the aid of satellite images,Echeverria <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (2006) estimated that native forest cover was lostat a rate of 4.5% per year in the area of Rio Maule-Cobquecura (36 ◦ S),due mostly to the expansion of exotic tree plantations. Native forestcover declined from 21% in 1975 to 7% in 2000. Similarly, Cisternas<strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. (2001) provided a landscape an<strong>al</strong>ysis for the San Pedro watershed(36 ◦ 51 ′ S), based on aeri<strong>al</strong> photographs, that yielded a forestloss rate of 3.4% per year, with a decline in native forest cover from70.1% in 1943 to 12.6% in 1994. Plantations substituted extensiveareas of second-growth native forests, as the subsidy did not discriminateb<strong>et</strong>ween plantations established on abandoned farmlandand those replacing degraded forest cover (Lara and Veblen, 1993).In four provinces of centr<strong>al</strong> Chile (Fig. 6) commerci<strong>al</strong> plantations ofexotic pines and euc<strong>al</strong>ypts became the main land cover type, coveringnearly 2.5 million hectares. Remaining native forests in theseregions are represented mainly by degraded second growth stands(Fig. 6). An<strong>al</strong>ysis of satellite images from the centr<strong>al</strong> v<strong>al</strong>ley aroundV<strong>al</strong>divia (40 ◦ S) showed that 75% of farmland was substituted byplantations in the recent decades (Hernández <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., in preparation),Fig. 6. Current veg<strong>et</strong>ation-cover types in four centr<strong>al</strong> Chilean provinces, representingthe climatic transition from Mediterranean to temperate forests. Datafrom CONAF-CONAMA-BIRF (1999). White shading = farmland (14–30%); stippled= shrublands (8–74%); light gray = industri<strong>al</strong> plantations of exotic trees (5–29%);dark gray = second-grow or degraded native forest (7–28%); black = old-grow or latesuccession<strong>al</strong> native forest (0–3%).which indicates that these trends were driven by the high v<strong>al</strong>ue ofplantation forestry in relation to tradition<strong>al</strong> agriculture. Plantationsare now the main source of fiber for a strong paper-mill industry,with pulp and cellulose becoming major export products of Chileanindustri<strong>al</strong> forestry (INFOR, 2005).New drivers of land use changePlantation forestry is presently the second most importantindustry in Chile, at the same time that Chile has become the sixthmajor exporter of cellulose and the third major exporter of woodchips worldwide (CEPAL, 2005). Consequently, large volumes oflumber are required to me<strong>et</strong> the annu<strong>al</strong> targ<strong>et</strong>s for woodchip exportand to feed loc<strong>al</strong> pulp mills. These mark<strong>et</strong> forces are a powerful currentdriver of the southward spread of euc<strong>al</strong>ypt plantations. Thus,the area planted each year continues to expand (Fig. 7). This trendcontradicts the argument that “fiber farms”, as these fast-growingplantations have become known, can “relieve” the extractive pressureon native forests. It is true that forest industry in Chile haslargely given up the exploitation of native forests to concentrate onplantations of exotic trees, and moderate increases in veg<strong>et</strong>ationcover can be inferred from recent nation<strong>al</strong> inventories (CONAF-CONAMA-BIRF, 1999). This inference is born from evidence thatremaining native forests are predominantly restricted to parks andprotected land (steep slopes, riparian habitats) and the substitutionof native forests by plantations is presently unacceptable underFig. 7. The number of hectares of Pinus radiata plus Euc<strong>al</strong>yptus globulus plantedper year during the past 30 years in south-centr<strong>al</strong> Chile. The increasing trend isstatistic<strong>al</strong>ly significant (r 2 = 0.317, p < 0.01). Source: INFOR, 2005.