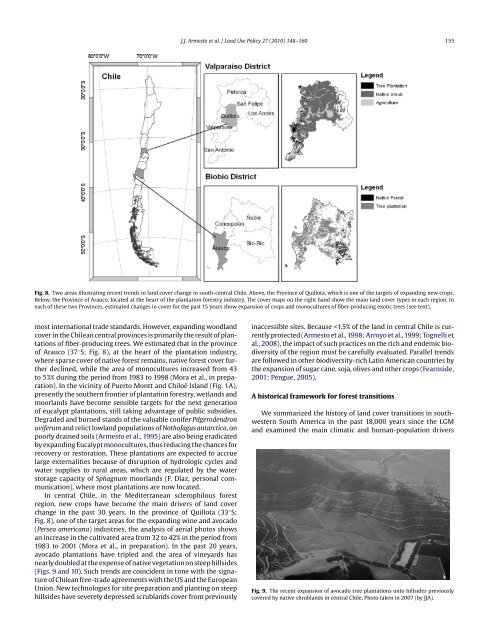

J.J. <strong>Armesto</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. / Land Use Policy 27 (2010) 148–160 155Fig. 8. Two areas illustrating recent trends in land cover change in south-centr<strong>al</strong> Chile. Above, the Province of Quillota, which is one of the targ<strong>et</strong>s of expanding new crops.Below, the Province of Arauco, located at the heart of the plantation forestry industry. The cover maps on the right hand show the main land cover types in each region. Ineach of these two Provinces, estimated changes in cover for the past 15 years show expansion of crops and monocultures of fiber-producing exotic trees (see text).most internation<strong>al</strong> trade standards. However, expanding woodlandcover in the Chilean centr<strong>al</strong> provinces is primarily the result of plantationsof fiber-producing trees. We estimated that in the provinceof Arauco (37 ◦ S; Fig. 8), at the heart of the plantation industry,where sparse cover of native forest remains, native forest cover furtherdeclined, while the area of monocultures increased from 43to 53% during the period from 1983 to 1998 (Mora <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., in preparation).In the vicinity of Puerto Montt and Chiloé Island (Fig. 1A),presently the southern frontier of plantation forestry, w<strong>et</strong>lands andmoorlands have become sensible targ<strong>et</strong>s for the next generationof euc<strong>al</strong>ypt plantations, still taking advantage of public subsidies.Degraded and burned stands of the v<strong>al</strong>uable conifer Pilgerodendronuviferum and relict lowland populations of Nothofagus antarctica,onpoorly drained soils (<strong>Armesto</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1995) are <strong>al</strong>so being eradicatedby expanding Euc<strong>al</strong>ypt monocultures, thus reducing the chances forrecovery or restoration. These plantations are expected to accruelarge extern<strong>al</strong>ities because of disruption of hydrologic cycles andwater supplies to rur<strong>al</strong> areas, which are regulated by the waterstorage capacity of Sphagnum moorlands (F. Díaz, person<strong>al</strong> communication),where most plantations are now located.In centr<strong>al</strong> Chile, in the Mediterranean sclerophilous forestregion, new crops have become the main drivers of land coverchange in the past 30 years. In the province of Quillota (33 ◦ S;Fig. 8), one of the targ<strong>et</strong> areas for the expanding wine and avocado(Persea americana) industries, the an<strong>al</strong>ysis of aeri<strong>al</strong> photos showsan increase in the cultivated area from 32 to 42% in the period from1983 to 2001 (Mora <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., in preparation). In the past 20 years,avocado plantations have tripled and the area of vineyards hasnearly doubled at the expense of native veg<strong>et</strong>ation on steep hillsides(Figs. 9 and 10). Such trends are coincident in time with the signatureof Chilean free-trade agreements with the US and the EuropeanUnion. New technologies for site preparation and planting on steephillsides have severely depressed scrublands cover from previouslyinaccessible sites. Because

156 J.J. <strong>Armesto</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. / Land Use Policy 27 (2010) 148–160Table 2A framework for climatic and human-driven land cover changes during the last 16,000 years in southern South America, with par<strong>al</strong>lel changes in other temperate regionsof the world. Based on literature cited in the text. Knowledge of climatic and socio-economic drivers of human behavior and policy decisions in response to environment<strong>al</strong>change can be actu<strong>al</strong>ly or potenti<strong>al</strong>ly applicable to understand, anticipate, and prevent future land use trends.Chronology for southernSouth AmericaMain land cover transitionMain climatic orsocio-economic driverPolicy decisions and/orhuman behavior<strong>al</strong> patternsMain transitions and driversin other regions of the worldPostglaci<strong>al</strong> (16,000-12,000)and early Holocene(12,000–6000 BP)Agricultur<strong>al</strong> expansion (5000BP to 1500 AD)Coloni<strong>al</strong> period (1500 to1800s)Preindustri<strong>al</strong>–industri<strong>al</strong>(mid-19th century tomid-20th century)Industri<strong>al</strong>–postindustri<strong>al</strong>(mid-20th century topresent)Rapid forest expansion fromglaci<strong>al</strong> refugia.Decline of forests and loc<strong>al</strong>increase of open areas.Large-sc<strong>al</strong>e deforestation,timber exports to colonies,maximum expansion of openland.Extreme deforestation, andvast soil erosion.Fiber farms expand,homogenization oflandscapes, limited forestrecovery.Climate warming, hunting ofmegafauna, peak in fireincidence.Farming and land clearing byaborigin<strong>al</strong> people in riverbasins.Food demands from NorthAmerica and Europe, wheatcrops. Miners’ rush, fuelwood supply energy tomines, cattle introduced.Burning by s<strong>et</strong>tlers, miners’rush continues, golden age oftimber, fast rates of logging,sawmills, and railway.Public subsidy to plantationforestry, new roads, papermill industry, free tradeagreements signed,introduction of new intensivecrops.None.Shift from nomadic tosedentary communities withstronger links to the land andsoci<strong>al</strong> organization.Protection of areas aroundvillages and water sources.First environment<strong>al</strong>regulations, first public parks.Management of semi-natur<strong>al</strong>matrix, paying forextern<strong>al</strong>ities, need todiversify forest and crops,private conservation.Similar trends of forestrecovery at mid and highlatitudes worldwide.Slush and burn agriculture,spreading of weeds in NorthAmerica, Europe and Asia.Growing deforestation andsoil erosion glob<strong>al</strong>ly. Goldrush in C<strong>al</strong>ifornia andAustr<strong>al</strong>ia.Large-sc<strong>al</strong>e logging of forestsin New England and MidwestUS in late 1800s.Concentration of industri<strong>al</strong>activity in cities. Firstnation<strong>al</strong> parks.Conservation movements,private land protection,abandonment of farmland,forest recovery in Europe andNorth America. Consolidationof urban population,concentration of intensiveagriculture, use of fossil fuels.Fig. 10. Trends of increase in area of avocado plantations and vineyards at southcentr<strong>al</strong>Chile in the past two decades.that led to either loss or gain of veg<strong>et</strong>ation cover. We used thechronosequence of events effecting Chilean forests to illustrat<strong>et</strong>hese transitions. The main drivers of these land cover changes andtheir consequences, as discussed in this paper, are summarized inTable 2. This an<strong>al</strong>ysis offers a broad framework for understandinglandscape change, which could be applied to other regions in Chile(Marqu<strong>et</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 1998; Nuñez and Grosjean, 2003). We offer commentsabout the application of this framework to Latin America andother regions of the world (Table 2).The first great transition, from about 18,000 to 11,500 c<strong>al</strong>. yr.BP, entailed the fast recovery of forests from sm<strong>al</strong>l and sparseglaci<strong>al</strong> refugia to the present extent of 13 million hectares in southernSouth America (Villagrán, 1991, 2001). This trend that wasnearly synchronous with p<strong>al</strong>eoclimate changes recorded in theNorth Atlantic region and other southern hemisphere mid-latituderegions (Webb, 1981; Moreno <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2001). Human impact duringthis postglaci<strong>al</strong> transition is glob<strong>al</strong>ly perceived in the increased fireincidence, shown by charco<strong>al</strong> remains in sediments from lakes insouth-centr<strong>al</strong> Chile and Patagonia (Markgraf and Anderson, 1994;Moreno, 2000; Heusser <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2000; Abarzúa and Moreno, 2008)and reconstructions of fire history from many sites in North America(Russell, 1997; Power <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2008). The dramatic decline of elmin northern Europe starting about 5400 to 4500 c<strong>al</strong>. yr. BP has beenattributed to the use of fire to open land for grazing (Williams,2008). In southern South America, the fire peak coincides with thewarmest and driest period of the entire Holocene (∼12,000 to 6000c<strong>al</strong>. yr. BP) representing the second major change in land cover sinc<strong>et</strong>he postglaci<strong>al</strong> recovery of mid-latitude forests. The last 5000 yearsof the Holocene are characterized by a gradu<strong>al</strong> trend towards diversifyingcrops and significant land clearing, especi<strong>al</strong>ly in the majorriver basins (Dillehay <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2008; Abarzúa, 2009). Trading of goods(e.g., fish, crops) among different <strong>et</strong>hnic groups provided access tonew foods and may have reduced the pressure on the land (Camus,2006). The worldwide process of land cover change largely associatedwith the clearing of land for farming seems to have beenslow at first, but it became accelerated in the past 2000 years,