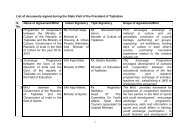

IP_ Tagore Issue - Final.indd - high commission of india mauritius

IP_ Tagore Issue - Final.indd - high commission of india mauritius

IP_ Tagore Issue - Final.indd - high commission of india mauritius

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

play-acting in the school. Theyplayed games in the afternoon.<strong>Tagore</strong> thought that man isborn in the world with onlyone advice from God – thatis – ‘Express yourself!’ Thereforechildren <strong>of</strong> the ‘Poet’s school’were allowed to expressthemselves through tune andrhythm, lines and colour, andthrough dance and acting. EveryTuesday there would be literarymeetings in the ‘ashrama’where children read out theirstories and poems, sang anddanced and put up short playsin the presence <strong>of</strong> all theashramites (the inmates <strong>of</strong> theashrama). In their classes tooit was the self-expression thatwould be encouraged and notcramming <strong>of</strong> possible questionsand answers. They wereencouraged to use their limbsAn open-air class at the Patha-Bhavana today(left) and Basantotsav celebration (below).Samiran Nandy, Rabindra-Bhavana, Visva-BharatiSamiran Nandy, Rabindra-Bhavana, Visva-BharatiINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 14 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 15

in craft classes and gardeningclasses. It was the belief <strong>of</strong> thepoet that by using their limbseven dull students improved intheir academics.<strong>Tagore</strong> thought that childrenhad a three-fold relationshipwith their environment,especially in the relationshipbetween Nature and Man.At the lowest level childrenlearned to use theirenvironment. This was the level<strong>of</strong> ‘Karma’ (action). Man useshis environment for a living –he has to till the soil, buildhis house, weave his clothes.Therefore, children must betrained in various physicalactivities. At the next levelthey must gather knowledgeabout their environment. Theymust search for natural rulesand correlations, and formconclusions. They have to lookfor unity in the world <strong>of</strong> diversity.Only then would they be ableto achieve the true Jnana or‘knowledge’. This way, theywould try to gather knowledgeabout Nature and Man.At the <strong>high</strong>est level, it wasPrema (love) that binds anindividual to Nature and to theworld <strong>of</strong> Man. Through lovean individual loses his identityand becomes one with theworld. In the Poet’s schoolall such relationships werecultivated.<strong>Tagore</strong> was a believer inunity where each elementhad its own space. Thus,compartmentalization <strong>of</strong> one’sknowledge <strong>of</strong> and skill fora particular work and lovefor it were not exclusive toone another – they alwaysoverlapped. But for the sake<strong>of</strong> better understanding, thesedivisions are made.<strong>Tagore</strong> also believed thatnone <strong>of</strong> these three levelscould be ignored for a properdevelopment <strong>of</strong> personality.One must give its due toKarma, Jnana and Prema forthe fullest growth <strong>of</strong> man.The finer things in life cannever be taught in a class.Children imbibe them fromthe environment or from thepersonalities around them.<strong>Tagore</strong> believed that thesequalities were already therein the child. Therefore, it wasthought essential to createa proper environment inthe school to bring out thedormant qualities in a child.The environment created atSantiniketan was, therefore,most appropriate for theeducation <strong>of</strong> children. Thechildren grew up in the midst<strong>of</strong> nature, however, onlyclose proximity to nature wasnot enough. It had to be aconscious encounter.Santiniketan was a beautifulplace with shady mangoand other fruit-bearing trees,under which children attendedtheir classes. Tall Sal treesshaded the avenues. Thechildren had their gardensto look after. There wereNature-study classes as part <strong>of</strong>their curriculum. They learntabout trees, birds and insectsat the Ashrama. Also, seasonalfestivals were celebrated tomake the children conscious<strong>of</strong> the spirit <strong>of</strong> the season,and establish a connect to theagricultural cycle.It was an experience for thechildren to sing <strong>Tagore</strong>’s songs,going round the Ashrama inthe moonlit night to feel thespirit <strong>of</strong> spring in their minds.What could be a better way <strong>of</strong>Kala Bhavana Painting class in progress in early yearsgrowing up in nature? <strong>Tagore</strong>felt that a person was not fit tobe a teacher if the child in hismind was not alive still. Theyhad to share their experienceswith the children.Then the children were madeaware <strong>of</strong> the problems <strong>of</strong>the villagers living aroundSantiniketan. They regularlyvisited nearby villages to studytheir life and problems.The school subjects weretaught through experiments anddifferent types <strong>of</strong> experiencesas far as practical. Creativityin children was alwaysencouraged.Wednesday was the weeklyholiday in the school instead <strong>of</strong>Sunday.The children in the morningattended the weekly servicein the prayer hall. Theservice essentially was nondenominational– not cateringto one or the other dominantreligions. Devotional songs by<strong>Tagore</strong> were sung. Carefullycreated and crafted, theseprayers would be such thatthey would be acceptableRabindra-Bhavana, Visva-BharatiINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 16 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 17

to everybody. Once <strong>Tagore</strong>was asked if he would liketo recommend the kind <strong>of</strong>religious training the schoolsshould ideally impart. Heclearly replied that no religiousinstruction should be given inschools. There should rather bean effort to cultivate a ‘sense<strong>of</strong> infinity’ in the minds <strong>of</strong>children. That we are a part<strong>of</strong> a very vast and wonderfulcreation should somehow beconveyed; a sense <strong>of</strong> awe aboutthis huge creativity should begiven to the children.Santiniketan has always beenlike a big family. Teachers knowall the students personally,and vice versa. The wives <strong>of</strong>the teachers are like mothersto the students. Therefore, theinstitution had to be small for<strong>Tagore</strong>’s ideals to be fruitful.Big institutions have a differentlogic <strong>of</strong> their own. It is, thusan environment <strong>of</strong> beauty, loveand co-operation. Competitionhas no place here. <strong>Tagore</strong> usedthe word ‘becoming’ which hethought was more importantthan anything else in the Poet’sSchool.◆The author was the Principal <strong>of</strong> Patha-Bhavana, the school set up by Rabindranath<strong>Tagore</strong> at Santiniketan.Samiran NandyPrayer in progress today in the heritageUpasana-griha (Prayer hall).INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 18 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 19

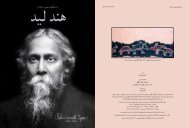

<strong>Tagore</strong>, Gitanjaliand the Nobel PrizeNILANJAN BANERJEE<strong>Tagore</strong> felt “homesick for the wide world.” Further, he wasconstantly struggling to overcome the barriers <strong>of</strong> language.He thought that the Nobel Prize awarded by the SwedishAcademy “brought the distant near, and has made thestranger a brother.”Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>, in a letter to E.J. Thompson, wrote in1916, “I feel homesick for the wide world.” A few years beforehis death, he criticized his own poetry for not being universalin expression, arguing that his paintings had rather overcome thebarriers <strong>of</strong> language. It was likely that <strong>Tagore</strong>, a seeker <strong>of</strong> universalconcord, would not have been satisfied in restricting himself to anaudience in the colonial, undivided Bengal where he was born andraised in the second half <strong>of</strong> the nineteenth century. Rabindranath,who translated Shakespeare’s Macbeth at the age <strong>of</strong> thirteen, turnedout to be a prolific bilingual writer <strong>of</strong> his time <strong>of</strong>ten taking pleasurein translating his own works into English.It was in June 1912 that Rabindranath desired to share the Englishtranslations <strong>of</strong> his poems with his British painter friend WilliamRothenstein (1872-1945) in London, (Rothenstein later went onto become the Principal <strong>of</strong> the Royal College <strong>of</strong> Art). A leathercase, containing the translatedmanuscript entrusted to <strong>Tagore</strong>’sson Rathindranath (1888-1961), was discovered to bemissing. Rushing to the Left-Luggage Office <strong>of</strong> the Britishunderground, Rathindranathmanaged to retrieve thebaggage that he had left in thetrain by mistake while gettingdown at the Charing Cross tubestation. Rathindranath wrotein his autobiography, “I have<strong>of</strong>ten wondered what shapethe course <strong>of</strong> events mighthave taken if the manuscript<strong>of</strong> Gitanjali had been lostdue to my negligence.” Therecovered translations came tobe published in the form <strong>of</strong> abook Gitanjali (Song Offerings),on 1 November, 1912 by theIndia Society <strong>of</strong> London with anintroduction by the English poetW.B. Yeats (1865-1939).In 1910, <strong>Tagore</strong> published abook <strong>of</strong> poems in Bengali titledGitanjali. By that time he hadestablished himself as a poet,an essayist, novelist, short storywriter, a composer <strong>of</strong> numeroussongs, and a unique educatorwith an experimental school forchildren at Santiniketan. Heunderwent a number <strong>of</strong> personaltragedies by the time Gitanjaliwas published. <strong>Tagore</strong> lost hismother Sarada Devi (1875),adored sister-in-law Kadambari(1884), wife Mrinalini (1902),second daughter Renuka (1903),father Debendranath (1905),and youngest son SamindranathNobel Medallion (top), the reverse <strong>of</strong>the medal (middle) and the title page<strong>of</strong> the 1912 Gitanjali.(1907) within the short span<strong>of</strong> thirty two years. Thisexperience with death refinedhis sensibilities and gave himthe impetus to consider life inits contrasting realities with joyand wonder.In the beginning <strong>of</strong> 1912,<strong>Tagore</strong> became seriously ill.Cancelling a planned visitto England, he went to hisancestral home in Silaidah (nowin Bangladesh) on the banks <strong>of</strong>the river Padma for a changewhere he translated some <strong>of</strong>his poems from their original inBengali. After his recovery hesailed for England in May 1912,without any specific mission,with the mind <strong>of</strong> a wayfaringpoet, primarily obeying hisdoctor’s advice. During hislong sea voyage to England, hecontinued his experiments withtranslations presumably with adesire to connect to a distantand wider horizon. Before 1912,<strong>Tagore</strong> had translated only acouple <strong>of</strong> his poems.William Rothenstein, whoknew Rabindranath since hisvisit to India during 1910-1911,introduced <strong>Tagore</strong> and hispoetry to his illustrious circle<strong>of</strong> friends including W.B. Yeats,Thomas Sturge Moore (1870-1944), Ernest Rhys (1859-1946),Ezra Pound (1885-1972), MaySinclair (or, Mary Amelia St.Clair, 1863-1946), StopfordBrooke (1832-1916) amongmany others. They wereinstantly carried away withINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 20 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 21

uying its rights, publishing tensubsequent editions <strong>of</strong> the titlewithin nine months betweenMarch and November, 1913.While the Bengali Gitanjaliwas brought out without anydedication, <strong>Tagore</strong> dedicated hisfirst English anthology <strong>of</strong> poemsto Rothenstein as a token <strong>of</strong>their friendship that lasted tillthe death <strong>of</strong> the poet in 1941.<strong>Tagore</strong>, left England in October,1912 for America before hisEnglish Gitanjali could bepublished and returned to Indiain September, 1913. Ezra Poundand Harriet Monroe (1860-1936)took the initiative in publishingsix poems <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong> in theprestigious American magazinePoetry with a note by Poundin December, 1912. Gitanjalireceived wonderful reviews insome <strong>of</strong> the leading newspapersand literary magazines includingThe Times Literary Supplement,Manchester Guardian, and TheNation among others, shortlyafter the publication <strong>of</strong> thebook.The British littérateur ThomasSturge Moore, in his individualcapacity as the Fellow <strong>of</strong> theRoyal Society <strong>of</strong> Literature <strong>of</strong> theNobel Prize citation‘Where the mind is without fear!’: A poem from Gitanjali in <strong>Tagore</strong>’s calligraphythe mystic vision and rhetoricsplendour <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong>’s poetry.Yeats suggested minor changesin the prose translations <strong>of</strong> theGitanjali songs. Speaking onthe charm <strong>of</strong> Gitanjali, Yeatswrote in his introduction:“… These prose translations havestirred my blood as nothing hasfor years. …I have carried themanuscript <strong>of</strong> these translationswith me for days, reading it inrailway trains, or on the top <strong>of</strong>omnibuses and in restaurants, and Ihave <strong>of</strong>ten had to close it lest somestranger would see how much itmoved me.”While the Bengali Gitanjali hadone hundred and eighty threepoems, the English versioncontained one hundred andthree poems from ten previouslypublished anthologies includingfifty three poems from itsBengali namesake. It was dueto Rothenstein’s efforts thatthe India Society <strong>of</strong> Londonbrought out these translationsas a book. A limited edition<strong>of</strong> seven hundred and fiftycopies was printed, amongwhich two hundred and fiftycopies were for sale. Thebook was received with muchenthusiasm in England and theMacmillan Press <strong>of</strong> London didnot miss the opportunity <strong>of</strong>INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 22 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 23

United Kingdom recommendedRabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>’s name forthe Nobel Prize for literatureto the Swedish Academy whileninety seven other members<strong>of</strong> the Society collectivelyrecommended the name <strong>of</strong>novelist Thomas Hardy forthe award. Initially <strong>Tagore</strong>’snomination was stronglyopposed by the Chairman <strong>of</strong>the Academy Harald Hijarne.Vocal members <strong>of</strong> the Academylike Per Hallstorm, Esais HenrikVilhelm Tenger (who knewBengali) and Carl Gustaf Vernervon Heidenstam, familiarwith <strong>Tagore</strong>’s literary genius,wholeheartedly supported hisnomination. <strong>Tagore</strong>’s namewas finalized for the awardfrom a total <strong>of</strong> twenty eightnominations “because <strong>of</strong> hispr<strong>of</strong>oundly sensitive, freshand beautiful verse, by which,with consummate skill, hehas made his poetic thought,expressed in his own Englishwords, a part <strong>of</strong> the literature<strong>of</strong> the West.”A cablegram from the NobelCommittee arrived in Kolkataon 14 November 1913 andthe news was communicatedto <strong>Tagore</strong> at Santiniketanthrough a series <strong>of</strong> telegrams.Memoirs reveal that the whole<strong>of</strong> Santiniketan rejoiced at thisachievement <strong>of</strong> the Poet.held that the ‘Novel’ prizecame to Santiniketan onlyfor the deserving novels that<strong>Tagore</strong> had written. Amidstthis unprecedented storm <strong>of</strong>excitement, a grand felicitationwas organized on the 23 rd <strong>of</strong>November in 1913 at Santiniketnin honour <strong>of</strong> the Poet, presidedover by his scientist friendJagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937). A special train reachedBolpur from Kolkata with fivehundred enthusiasts. <strong>Tagore</strong>was led to the venue where henoticed some <strong>of</strong> his critics whohad criticized him personally onvarious occasions in the past.These individuals were nowgathered to felicitate him as thePoet had received recognitionoverseas. <strong>Tagore</strong>’s speech,which echoed his immediateill-feelings at the sight <strong>of</strong> hisdetractors, disappointed many<strong>of</strong> his genuine admirers whenhe expressed, “I can only raisethis cup <strong>of</strong> your honour to mylips, I cannot drink it with allmy heart.” Overnight, <strong>Tagore</strong>was inundated with attentionand praise which made himwrite to Rothenstein in 1913,“It is almost as bad as tying atin can to a dog’s tail makingit impossible for him to move,without creating noise andcrowds all along.”<strong>Tagore</strong> could not be present inSweden to receive the NobelPrize as the first Asian recipient<strong>of</strong> the award and a telegramfrom him was read out at thetraditional Nobel Banquetwhich stated “I beg to conveyto the Swedish Academy mygrateful appreciation <strong>of</strong> thebreadth <strong>of</strong> understanding whichhas brought the distant nearand has made the stranger abrother.” The Nobel medallionand the diploma were sent toLord Carmichael (1859-1926),Governor <strong>of</strong> Bengal, whoA portrait <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong> by William Rothenstein,his painter-friend (right) and <strong>Tagore</strong> withRothenstein and son, Rathindranath.handed them over to the Poetat a ceremony on 29 January,1914 at the Governor’s House inKolkata.Gitanjali and the Nobel Prizeset <strong>Tagore</strong> on the world stageraising him to the glorifiedstatus <strong>of</strong> Visva Kabi, the WorldPoet, who could celebrate lifebeyond any boundaries:“I have had my invitation to thisworld’s festival, and thus my lifehas been blessed. My eyes haveseen and my ears have heard.”(Gitanjali, 16)◆The author is a poet and a painter who iscurrently designing several museums on thelife and times <strong>of</strong> Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong> forVisva Bharati.While some students debatedthat <strong>Tagore</strong> had securedthe ‘Nobel Prize’ for hispr<strong>of</strong>ound nobility, othersFacsimile <strong>of</strong> a page from The Statesman(daily) <strong>of</strong> Nov 15, 1913 announcingRabindranath getting the covetedNobel Prize.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 24 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 25

RABINDRANATH TAGOREAS A PAINTERSANJOY KUMAR MALLIKThe multifarious personality <strong>of</strong> Rabindranathcovered diverse terrains <strong>of</strong> creative expression,but he ventured into the world <strong>of</strong> paintingquite late in life.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 27

In a letter to his daughter,Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong> hadonce commented thatpainting wasn’t really hisforte – had it been so hewould have demonstrated whatneeded to be done. But muchbefore this lament, in an earlierepistle addressed to J.C. Bose(1858-1937), he had mentionedin an ebullient tone that itwould surprise the latter tolearn that he had been paintingin a sketchbook, although theeffort with the pencil was beingovertaken by the effort withthe eraser, such that Raphaelcould lie peacefully in hisgrave without the fear <strong>of</strong> beingrivaled.The multifarious personality <strong>of</strong>Rabindranath covered diverseterrains <strong>of</strong> creative expression,but he ventured into the world<strong>Tagore</strong> selecting his paintings in Moscow<strong>of</strong> painting quite late in life.The pages <strong>of</strong> his manuscripttitled Purabi, a book <strong>of</strong>poems published in 1924, isconventionally identified as thefirst evidence <strong>of</strong> articulationthrough full fledged visualimages. In the process <strong>of</strong>editing and altering the text <strong>of</strong>these poems, the poet beganjoining together the struck-outwords in rhythmic patterns <strong>of</strong>linear scribbles, with the resultthat these connected erasuresemerged into consolidated,united and independent identityas fantastic visual forms. Aboutthis process, he later wrote: “Ihad come to know that rhythmgives reality to that which isdesultory, which is insignificantin itself. And therefore, whenthe scratches in my manuscriptcried like sinners, for salvation<strong>Tagore</strong> at his exhibition at the GalleryPigalle with Victoria Ocampo (seated).and assailed my eyes with theugliness <strong>of</strong> their irrelevance,I <strong>of</strong>ten took more time inrescuing them into a mercifulfinality <strong>of</strong> rhythm than incarrying on what was myobvious task.” (‘My pictures’, 1;28 th May 1930).The Purabi correctivecancellations, deleting theunnecessary and unwanted,finally fused together intoa unity <strong>of</strong> design; but morethan that, this rhythmicinterrelationship gave birthto a host <strong>of</strong> unique forms,most <strong>of</strong>ten queer, curiousand grotesque. This nearlysubconscious birth <strong>of</strong> forms,springing up unpremeditatedon the sheet <strong>of</strong> paper, is anecessary corollary to the poet’sinnate concern with rhythm. Itwas not the sheer delectablebeauty <strong>of</strong> swirling arabesquesAll paintings illustrated in this essay areby Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>.that interested the poet, but theemergent unpredictable thatdelighted him. These creaturesmay certainly defy classificationaccording to strict conventions<strong>of</strong> zoology, but are very muchvalid as entities in a painter’sworld. They even possessdistinctly identifiable moods,emotions and characteristics,such that they becomepersonalities rather than blankforms.The manuscript is a privateand personal domain;as the presence <strong>of</strong> theseemergent forms began todemand more independentexistence, the poet-painterturned to full scale paintings.However, having originatedfrom the subconsciousplayfulness <strong>of</strong> the erasures,somewhat unfortunatelyand for a considerable time,Rabindranath’s pictorial practicetended to carry the stigma <strong>of</strong>being a dilettante’s dabble.While it is true that he didnot possess any academicinitiation into the domain <strong>of</strong>the visual arts, he did takelessons in painting in hischildhood, as most childrendo, from home-instructors.In his reminiscences titledChelebela (my childhood days)Rabindranath had recalled howin the interminable sequence<strong>of</strong> home-instructors, an artteacher would immediatelystep in once the instructor inphysical education had justleft. While that is no pleasantrecollection that may inspirelater indulgence in the visualarts, in the Jeebansmriti (Myreminiscences) he had recordeda slightly different childhoodmemory – at bed-time he wouldstare at the patterns <strong>of</strong> peelingINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 28 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 29

whitewash on the walls, andthese would induce a range <strong>of</strong>visual forms in his imaginationas he drifted <strong>of</strong>f to sleep. Onemay infer that Rabindranath didpossess the elemental faculty <strong>of</strong>visual imagination.By 1930, however, Rabindranathwas relatively confident <strong>of</strong> hisefforts as a painter. In a letterdated 26 th April addressed toIndira Devi (1873-1960), hewrote that it would surprisethe latter to learn the entirestory <strong>of</strong> how the once-poetRabindranath’s current identitywas that <strong>of</strong> a painter, though hewould rather modestly wait forposterity to bear that news toher rather than declare his ownachievements. He went on tomention that the inauguration<strong>of</strong> his exhibition was scheduledon the 2 nd <strong>of</strong> May, 1930 – thatthe harvest at the year-end hadbeen collected together onthese foreign shores. But, hewrote, he would prefer to leavethem behind, considering itfortunate that he had been ableto cross over with these fromthe ferry-wharf <strong>of</strong> his own land.Rabindranath’s acclaim fromthe series <strong>of</strong> foreign exhibitions(1930) even before one washeld in his own country hasbeen the other long-standingcause for suspicion <strong>of</strong> indulgentpraise. What counters thesedoubts is the consistency <strong>of</strong>INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 30 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 31

his pictorial quest and theenormous output – scholarsclaim that he had broughtalong as many as fourhundred paintings for the1930 exhibitions. What is <strong>of</strong>interest beyond numbers,are the choices exercised byRabindranath as a painter.In a period when nationalistrevivalism was triumphantin the country, he had thestrength <strong>of</strong> will to proposea larger vision beyond therestrictive criteria <strong>of</strong> national/geographical boundaries inmatters <strong>of</strong> creative expression.In fact, it is tempting to viewRabindranath’s pictorial practiceagainst the phrase that assumedthe role <strong>of</strong> a guiding motto forVisva Bharati, the university heinstituted: yatra viśva bhavatieka nidam – where the wholeworld comes to meet as in asingle nest. This catholicitydistinguished Rabindranath’screative process, and hisapproach to the notion <strong>of</strong>tradition was thereby liberated.Coupled with this, his Europeantours had probably contributedconsiderably to make the art<strong>of</strong> those lands a directly feltexperience. But even whenone identifies, for instance,echoes <strong>of</strong> the expressionistic inthe paintings <strong>of</strong> Rabindranath,the images in their ultimateINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 32 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 33

totality <strong>of</strong> visual language are soutterly individual that they defycategorization into strait-jackets<strong>of</strong> stylistic periodization ormovements in world art.It is, therefore, necessary tocomprehend Rabindranath’schoice <strong>of</strong> themes in conjunctionwith, and as a logical corollary<strong>of</strong>, his choice in the realm <strong>of</strong>pictorial language. Not onlydid he opt not to hark backto past pictorial traditions, healso rejected associations <strong>of</strong>the literary. Even when hispictorial compositions deal withdramatic ensembles <strong>of</strong> multiplehuman figures, the narrativeis entirely contained withinthe perimeter <strong>of</strong> the paintedpage, without drawing directreference to literary allusions,whether belonging to a sharedtradition or to those <strong>of</strong> his owncreation. What unfolds in front<strong>of</strong> the viewer <strong>of</strong> these paintingsis a narrative told exclusivelythrough the visual language– and meant to be read so aswell. The pictures that he drewfor his own books Shey andKhapchara are in the true spirit<strong>of</strong> illuminations, independentexpressions in their own right– complementary, rather thansupplementary, to the text.Then there are faces – bothmale and female – and theseare not illusive portraitsstanding in for an individual.They may have taken <strong>of</strong>f froma particular individual, but inthe final rendering becomerather character studies thanvisual impressions. It is thusthat they do not lack inpersonality but instead havedistinctly personal presences,with expressions ranging fromthe sullen and sombre to thecalm and contained, and rareinstances <strong>of</strong> the joyful or themerry. However, whicheverbe the particular expression,the painted faces invariablyexude a feeling <strong>of</strong> untoldmystery, as if the whole <strong>of</strong> apersonality is beyond completecomprehension.Very similarly, Rabindranath’slandscapes are hardlydescriptive passages such thatit may be nearly impossible todetermine the inspiring sourcein actual locations. Nonetheless,some <strong>of</strong> the glowing yellowskies behind the silhouette<strong>of</strong> trees in the foregroundmust invariably be the result<strong>of</strong> nature’s manifestation atSantiniketan. Once again, thefact, that despite a broadlygeneral identification thelandscapes remain largelynon-specific. These paintingsrendered with a dominant tone<strong>of</strong> chromatic emotions, wherenature’s mysteries unfurl beforeus through the liquid tones <strong>of</strong>colour.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 34 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 35

But above all, what drawsour attention from amongsthis entire collection is a series<strong>of</strong> reworked photographs.The May 1934 issue <strong>of</strong> theVisva-Bharati News carried aphoto-portrait <strong>of</strong> Rabindranathon the cover. A number <strong>of</strong> thesecovers were painted over byhim in ink, pastel and watercolour, transforming each <strong>of</strong>the faces into distinctly differingidentities. In many <strong>of</strong> these, theink scribbles and colour tonesspare the eyes which continueto glow piercingly out frombeneath the cloak <strong>of</strong> pictorialtransformation, but in a few hehad even painted over them.Not only does this exerciseaddress the issue <strong>of</strong> the ‘real’as an illusory appearance thatsubstitutes an object, it alsointroduces within the samedebate the issue <strong>of</strong> identity,especially when one realizesthat a couple <strong>of</strong> these reworkedfaces tend to look distinctlyfeminine.Addressing questions <strong>of</strong>considerably wider implicationsthan those that were <strong>of</strong>immediate concern to hiscontemporaries in the field<strong>of</strong> visual arts, Rabindranathpersonified a vision <strong>of</strong> muchlarger dimension. Approachingpictorial language from thevantage point <strong>of</strong> a widerhorizon, he indexed a directionand a possibility in pictorialpractice that was exemplarywithin the modern in Indian art.◆The author teaches Art History atVisva-Bharati, Santiniketan and taughtat the Maharaja Sayajirao University <strong>of</strong>Baroda.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 36 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 37

IN SEARCH OFA NEW LANGUAGEFOR THEATREABHIJIT SENThough Rabindranath maintained his search for an alternativelanguage for the theatre, yet it must be remembered that whenit came to matters <strong>of</strong> actual performance he was never rigidor inflexible. He combined in himself the roles <strong>of</strong> author-actorproducer,therefore, he was ever alert to the requirements <strong>of</strong>production and reception, kept adapting his staging principlesaccordingly, thereby giving his theatre a broader perspective.spectators sitting all aroundthe stage) but also the nondramaticforms like kathakata(Didactic story-telling tradition),kabigan (literally, poets’ songs),panchali (Poetic texts singingthe glory <strong>of</strong> a deity), or kirtan(religious singing in chorus).These forms were looked downupon as being fit only for theriffraff – as vulgarisation <strong>of</strong>the Hindu pantheon merely toentertain the lower sections <strong>of</strong>the society.Rabindranath and his brothershad a close association withthe theatre; one <strong>of</strong> them inparticular, Jyotirindranath(1849-1925), had writtenseveral plays for thepr<strong>of</strong>essional theatres, and hadexperimented extensively withWestern melodies, which,in turn, are said to haveinspired Rabindranath’s ownexperimentations in the earlyoperatic pieces like ValmikiPratibha (1881), Kalmrigaya(1882) and Mayar Khela (1888).Though some <strong>of</strong> his workswere staged in the publictheatre, Rabindranath himselfThere is no need for the paintedscene; I require only the scene <strong>of</strong>the mind. There the images willbe painted by brush-stokes <strong>of</strong> themelodious tune.In a prelude that he lateradded to his play Phalguni,Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong> makesKabisekhar (the poet) speakthese words, and when hewent on to play this role duringperformances <strong>of</strong> Phalguni(1915), the created and thecreator seemed to speak inthe same voice. Rabindranathhimself is known to have madesimilar declarations regardingthe theatre and the languagethat it needs to adopt, more soin our socio-cultural context.The Bengali theatre <strong>of</strong> the19 th century, which emergedas a product <strong>of</strong> the BengalRenaissance, was first, a colonialimportation, and second, anurban phenomenon. TheEnglish theatres in Calcutta,constructed chiefly for theentertainment <strong>of</strong> local Britishresidents, provided the modelsfor the theatres <strong>of</strong> the Bengalibaboos (the elite nouveauriche); so the theatres <strong>of</strong>Prasannakumar <strong>Tagore</strong> (1801-1886) or Nabinchandra Basu(with his home production <strong>of</strong>Vidyasundar in 1835) or thekings <strong>of</strong> Paikpara, all emulatedthat Western model. The otherimportant characteristic <strong>of</strong> thisBengali theatre was its urbannature. It evolved principally inthe city, patronized by the richelite classes, and increasinglypushed to the margins theearlier forms <strong>of</strong> popularperformance, which includednot only the jatra (a form <strong>of</strong>indigenous musical theatre withA scene from a dance drama by <strong>Tagore</strong>, also seen in the pictureINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 38 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 39

did not seem to care much forthe contemporary pr<strong>of</strong>essionaltheatre. He was envisaging a‘parallel theatre’, distinct fromthe contemporary pr<strong>of</strong>essionaltheatre.This search for a ‘paralleltheatre’ kept Rabindranathpreoccupied throughout hisentire dramatic career, thoughhe began with early dallianceswith the Western model – first,the operatic experimentationsin Valmiki-Pratibha (1881),Kalmrigaya (1882) and MayarKhela (1888); next, his use<strong>of</strong> the Shakespearean five-acttragic structure in blank verse,in Raja O Rani (1889) andVisarjan (1890). Most <strong>of</strong> theseearly performances weremarked by their use <strong>of</strong> overtrealistic stage-conventions,whether it was the illusion <strong>of</strong>a forest created with actualtrees for the staging <strong>of</strong> Valmiki-Pratibha (1890), or the stagestrewn with realistic stageproperties for the mounting <strong>of</strong>Visarjan (also 1890).Between Visarjan <strong>of</strong> 1890 andSarodatsav <strong>of</strong> 1908, despitesome sporadic attempts atplaywriting, there was virtually<strong>Tagore</strong> (left) and with Indira Devi (below) in Valmiki Pratibha.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 40 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 41

a gap <strong>of</strong> almost eighteenyears. The return to seriousdrama with Sarodatsav in 1908marks a major shift, not merelydramaturgical or theatricalbut even ideological. On theone hand, Rabindranath stillhad a sense <strong>of</strong> regard for the“great English” (whom heassociated with all that wasgood in the English culture)and distinguished them fromthe “little English” (whom helocated in the colonial masterswho had taken control <strong>of</strong> thiscountry). On the other hand, hewas influenced by the upsurge<strong>of</strong> the nationalist/anti-colonialideology that was increasinglygaining momentum.Oscillating between the two,Rabindranath had started to‘imagine’ a modern Indiannation that would recover much<strong>of</strong> its lost ancient glory. Thisurge was articulated in severalpoems, songs and essayscomposed during this period(among which were essayslike “Prachya O PaschatyaSabhyata”: 1901, “Nation ki”:1901, “Bharatvarsher Samaj”:1901, “Bharatvarsher Itihas”:1902, “Swadeshi Samaj”:1904). He was making aconscious departure from theBritish system <strong>of</strong> educationby founding a school inSantiniketan, approximating theIndian concept <strong>of</strong> a tapovan(1901). He was even activelyinvolved in the political protestsagainst the British-policy <strong>of</strong>partitioning Bengal; he steppedinto the streets singing songsand celebrating Rakshabandhanbetween members <strong>of</strong> the Hinduand Muslim communities (1905).Alongside, he was also‘imagining’ a new kind <strong>of</strong>theatre, which would besignificantly different from thecolonial mimicry then practisedon the public stage. This newtheory <strong>of</strong> theatre is formulatedin the essay “Rangamancha”(1903), in which he voiceshis disapproval <strong>of</strong> Westerntheatrical models, particularly <strong>of</strong>the realistic kind, and suggests areturn to our indigenous culturaltraditions. Rabindranath’sespousal <strong>of</strong> the cause <strong>of</strong> jatra isparticularly significant becausethis indicates his disapproval <strong>of</strong>both the colonial and the urbannature <strong>of</strong> the contemporaryBengali theatre. In the prefaceto Tapati (1929) he is critical<strong>of</strong> overt realism in theatre,particularly the use <strong>of</strong> paintedscenery. In imagining a “paralleltheatre”, he was trying to ridit <strong>of</strong> the unnecessary colonialtrappings and urban inflections.He was seeking to ensure thatthe imagination <strong>of</strong> the audiencewas not limited.When he moved to Santiniketanand the open-air environs <strong>of</strong> theashrama-school, Rabindranathwas able to put into practicehis notions <strong>of</strong> a ‘new’/‘parallel’theatre – both in the dramaticand theatrical languages –particularly in the productions<strong>of</strong> seasonal plays likeSarodotsav and Phalguni. Forthe 1911-Sarodatsav production(in which Rabindranath playedthe Sannyasi, or the ascetic),the students are reported tohave “decorated the stage withlotus flowers, kash, leavesand foliage”. Rabindranathallowed only a blue backclothto stand in for the sky, andmade Abanindranath removethe mica-sprinkled umbrella:“Rabikaka did not like it, andasked, ‘Why the royal umbrella?The stage should remain clearand fresh’; so saying, he hadthe umbrella removed.” Thebare stage was the appropriate<strong>Tagore</strong> as Raghupati in Visarjansetting for the two scenes <strong>of</strong>this play: the first located on theroad; the second, on the banks<strong>of</strong> the River Betashini.Again, for the first performance<strong>of</strong> Phalguni at Santiniketan(25 April 1915), the stage décorwas in tune with this poeticstructure <strong>of</strong> the play. As SitaDevi reminiscences, “the stagewas strewn with leaves andflowers. On the two sides weretwo swings on which two smallboys swung gleefully to theaccompaniment <strong>of</strong> the song…”Indira Devi, referring to a1916-Jorasanko performance(a charity show for the Bankurafamine), comments: “In place <strong>of</strong>the previous incongruous Westernimitation, a blue backdrophad been used; it is still usednow. Against it, was a singlebranch <strong>of</strong> a tree, with a singlered flower at its tip, under apale ray <strong>of</strong> the moonshine.”The reviewer <strong>of</strong> The Statesman(1 February 1916) noted: “‘Phalguni’ is a feast <strong>of</strong> colourand sound and joy. 1 ”Around this time, Rabindranathalso wrote what were arguablyhis maturer plays – Raja (1910),Dakghar (1917), Muktadhara(1922), Raktakarabi (1924)and Tasher Desh (1933). In1 Cited in Rudraprasad Chakrabarty, RangamanchaO Rabindranath: Samakalin Pratrikiya,pp. 125-126.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 42 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 43

each <strong>of</strong> these he experimentedconsiderably with thedramaturgical structure, butthe performance <strong>of</strong> the twoseasonal plays in the open-airambience <strong>of</strong> Santiniketanencapsulated his notions <strong>of</strong> anew theatre scenography in amanner that would not/couldnot be available in any otherludic space. Though Raja,Dakghar and Tasher Desh wereScene from a <strong>Tagore</strong> dance-dramaproduced by Rabindranath, hecould stage neither Muktadharanor Raktakarabi, though heread them out before severalpeople on different occasions.In 1926, Rabindranath tookyet another bold step as heintroduced dance as a medium<strong>of</strong> theatrical expression in hisplay Natir Puja. When it wasdecided to take the productionto Calcutta, there was a sense<strong>of</strong> unease because this waseffectively the first time that agirl from a respectable family– Gouri, the daughter <strong>of</strong> theartist, Nandalal Bose – wouldbe seen dancing in a theatricalperformance. To tide overthe problem, Rabindranathcreated the only male character<strong>of</strong> Upali and played the rolehimself. For the later dancedramas, he made it a pointto be seen on the stage ina bid to give legitimationto the performances. TheStatesman noted withapproval Rabindranath’son-stage presence during aperformance <strong>of</strong> Parishodh (theoriginal version <strong>of</strong> Shyama) inOctober 1936: “He makes thestage human. Everyone elseon the stage may be actingbut he is not. He is reality.Moreover he gives a dignity tothe performance – nautch istransformed into dance.” 2Rabindranath by this time hadpaid several visits to the FarEast: he went to Japan thrice,twice in 1916, and again in1924; to Java and Bali in 1927.To him, the Japanese dance“seemed like melody expressedthrough physical postures…The European dance is …half-acrobatics, half-dance…The Japanese dance is dancecomplete.” 3 Of the dance <strong>of</strong> Java2 The Statesman, 14 October 1936; cited inRudraprasad Chakrabarty, Rangamancha ORabindranath: Samakalin Pratrikiya , p.298;emphasis added.3 Japan yatri, Rabindra Rachanabali (CompleteWorks) Visva-Bharati Edition, vol. 10 (Calcutta:Visva-Bharati, 1990) p.428.he observed: “In their dramaticperformances [he uses the termyatra], there is dance from thebeginning to the end – in theirmovements, their combats,their amorous dalliances, eventheir clowning – everything isdance.” 4 This exposure to thedance-languages <strong>of</strong> the Far Eastinspired Rabindranath to evolvehis own theory <strong>of</strong> ‘theatre asdance’, which resulted in thecrop <strong>of</strong> the dance dramas <strong>of</strong>the final phase that commencedwith Shapmochan (1931). Withthe following trio – Chitrangada(1936), Chandalika (1939), andShyama (1939) – Rabindranathwent even further with hisexperimentations <strong>of</strong> the dancedramaform. Rabindranathadopted the style <strong>of</strong> kathakata,so that the lines <strong>of</strong> the proseplay (<strong>of</strong> 1933) were easilyset to tune. The Statesmanremarked: “The technique <strong>of</strong> thedance-drama in ‘Chandalika’ isin many ways a revival <strong>of</strong> theancient Indian form in whichthe dialogue is converted intosongs as background music,and is symbolically interpretedby the characters through thedances. 5 ”Though Rabindranathmaintained his search foran alternative language forthe theatre, yet it must be4 Java-yatrir patra, Rabindra Rachanabali,(Complete Works) Visva-Bharati Edition, vol. 10,1990, p.525.5 The Statesman, 10 February 1939, after theperformance at Sree Theatre in Calcutta (9 &10 Feb); cited in Rudraprasad Chakrabarty,Rangamancha O Rabindranath: SamakalinPratrikiya , pp. 271-272.remembered that when it cameto matters <strong>of</strong> actual performancehe was never rigid or inflexible.Because he combined in himselfthe roles <strong>of</strong> author-actorproducer,he was ever alert tothe requirements <strong>of</strong> productionand reception, kept adapting hisstaging principles accordingly,and thereby gave his theatre abroader perspective.If <strong>Tagore</strong> was imagining aliberally comprehensive concept<strong>of</strong> a nation, he was alsoimagining a more inclusive kind<strong>of</strong> theatre, as is evident fromhis later experiments (as actorand producer). He retained hisfondness for the indigenousresources but never believed ina blind replication <strong>of</strong> the jatraor yatra-model. At the sametime, though largely critical <strong>of</strong>the Western stage importations,he did not reject them outrightif they served the purposes<strong>of</strong> theatrical exigencies. As aproducer, he <strong>of</strong>ten concededto the actual staging conditionsat hand to uphold the model<strong>of</strong> an eclectic theatre wherecomponents realistic andnon-realistic, urban and rural,borrowed and indigenous,Western and Eastern, could allco-exist.◆The author teaches English literature atthe Department <strong>of</strong> English & Other ModernEuropean Languages, Visva-Bharati,Santiniketan.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 44 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 45

The Scientist in <strong>Tagore</strong>PARTHA GHOSE<strong>Tagore</strong> was a perfect antithesis <strong>of</strong> the cultural divide betweenthe sciences and the humanities so poignantly exposedby C.P. Snow in his “The Two Cultures”. All truly creativegeniuses have straddled this divide.Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>was a quintessentialpoet-philosopher. Yet,he had a deeply rational andscientific mind. He was a perfectantithesis <strong>of</strong> the cultural dividebetween the sciences and thehumanities so poignantly exposedby C.P. Snow (1905-1980) inhis “The Two Cultures” (1959).All truly creative geniuses havestraddled this divide. Darwin(1809-1882) wrote in The Origin<strong>of</strong> Species (1859):There is grandeur in this view <strong>of</strong>life, with its several powers, havingbeen originally breathed into afew forms or into one; and that,whilst this planet has gone cyclingon according to the fixed law <strong>of</strong>gravity, from so simple a beginningendless forms most beautiful andmost wonderful have been, and arebeing, evolved.Einstein admitted:A knowledge <strong>of</strong> the existence <strong>of</strong>something we cannot penetrate,our perceptions <strong>of</strong> the pr<strong>of</strong>oundestreason and the most radiant beauty,which only in their most primitiveforms are accessible to ourminds – it is this knowledge andthis emotion that constitutes truereligiosity; in this sense, and thisalone, I am a deeply religious man.(From ‘The World as I see it’ 1931).Rabindranath’s song akash bharasoorjo tara expresses the samesense <strong>of</strong> ‘wonder’ in the universe:The sky studded with the sun andstars, the universe throbbingwith life,In the midst <strong>of</strong> all thesehave I found my place –In wonder where<strong>of</strong> gushes forthmy song.The blood that courses throughmy veins can feel the tugOf the sway <strong>of</strong> time and the ebband flow that rocks the world –In wonder where<strong>of</strong> gushes forthmy song.Stepped have I gently on the grassalong the forest path,My mind beside itself with thestartling fragrance <strong>of</strong> flowers.The bounty <strong>of</strong> joy lies spread allaround –In wonder where<strong>of</strong> gushes forthmy song.I have strained my ears, openedmy eyes, poured my heart outon the earth,I have searched for the unknownwithin the known –In wonder where<strong>of</strong> gushes forthmy song.How wonderfully the poetdelineates the essence <strong>of</strong> sciencein the line, ‘I have searched forthe unknown within the known’.It is this aspect <strong>of</strong> science ratherthan its utilitarian value thatmakes it a deeply spiritual questand that fascinated Rabindranath.In the Preface to his only bookon science, Visva Parichay(1937), dedicated to the scientistSatyendranath Bose (1894-1974),he wrote about this fascinationfor science from his childhood– how his teacher Sitanath Dattaused to thrill him with simpledemonstrations like making theconvection currents in a glass <strong>of</strong>water visible with the help <strong>of</strong>sawdust. The differences betweenlayers <strong>of</strong> a continuous mass<strong>of</strong> water made obvious by themovements <strong>of</strong> the sawdust filledhim with a sense <strong>of</strong> wonder thatnever left him. According to him,this was the first time he realizedthat things that we thoughtlesslytake for granted as natural andsimple are, in fact, not so – thisset him wondering.The next wonder came when hewent with his father, MaharshiDebendranath, to the hills <strong>of</strong>Dalhousie in the Himalayas.As the sky became dark inthe evenings and the starscame out in their splendourand appeared to hang low,<strong>Tagore</strong> and Albert EinsteinMaharshi would point out tohim the constellations and theplanets, and tell him about theirdistances from the sun, theirperiods <strong>of</strong> revolution round thesun and many other properties.Rabindranath found this s<strong>of</strong>ascinating he began to writedown what he heard from hisfather. This was his first longessay in serial form, and it wason science. When he grewolder and could read English,he started reading every bookon astronomy that he could layhis hands on. Sometimes themathematics made it difficult forhim to understand what he wasINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 46 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 47

The Wayfaring PoetAMRIT SENThe sheer range <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong>’s travels fascinates us, consideringthe enormous difficulties and hardship he had to encounter.He was always eager to familiarize himself with other cultures,integrating the best aspects within his self and his institution.Among the many aspects<strong>of</strong> Rabindranath’smultifaceted personalitywas his fascination fortravel. “I am a wayfarer <strong>of</strong>the endless road”, he wrote.He travelled widely acrossEurope, America and Asiaat different points in his lifeand left behind a copiousrecord <strong>of</strong> his travels in hisletters, diaries and reflections.<strong>Tagore</strong> with Helen KellerFor <strong>Tagore</strong>, travel not onlybroadened his selfhood, it alsocontributed to his philosophy<strong>of</strong> internationalism and thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> his institutionVisva-Bharati.<strong>Tagore</strong>’s earliest experience<strong>of</strong> travel was his trip to theHimalayas in 1873 with hisfather Debendranath <strong>Tagore</strong>.Apart from inculcating abonding with nature, thistrip also provided a sense<strong>of</strong> freedom and explorationthat <strong>Tagore</strong> was to cherishthroughout his life.Accompanied by his brotherSatyendranath, the youngRabindranath travelled toEurope in 1878 to study law. Hereached London via Alexandriaand Paris and visited Brightonand Torquay. He enrolledhimself in the faculty <strong>of</strong> Arts andLaws in the University CollegeLondon, but his trip was cutshort and he returned to Indiain 1880. One <strong>of</strong> the interestingaspects <strong>of</strong> this trip was <strong>Tagore</strong>’srecognition <strong>of</strong> the freedom <strong>of</strong>women in European society,already discussed in anotheressay in this volume. The young<strong>Tagore</strong> in Argentina (right) and in Persia(below).Rabindranath also visited theBritish Parliament and noted thebustle <strong>of</strong> English life. <strong>Tagore</strong>undertook his second trip toEurope in 1890 with his brotherSatyendranath and his friendLoken Palit visiting London,Paris and Aden. On both thesetrips <strong>Tagore</strong> familiarized himselfwith western music and wasdrawn to European art, visitingthe National Gallery and theFrench exhibition.<strong>Tagore</strong>’s third trip to Europein 1912 was a landmark in hiscareer. Recuperating in England,the ailing Rabindranath camein contact with the leadingliterary personalities <strong>of</strong> Englandincluding William RothensteinW.B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, C.F.Andrews, Ernest Rhys andBertrand Russell (1872-1970).His translation <strong>of</strong> Gitanjali wasreceived with great enthusiasmas <strong>Tagore</strong> left for the USA. Hevisited Illinois, Chicago, Bostonand New York and deliveredseveral lectures at Harvard.On his return to England,his play The Post Office wasstaged by the Abbey TheatreCompany. <strong>Tagore</strong>’s growingINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 52 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 53

popularity as a poet can begauged from Rothenstein’sletter to him, “When you lastcame, it was as a stranger, withonly our unworthy selves to<strong>of</strong>fer our friendship; now youcome widely recognized poetand seer, with friends knownand unknown in a hundredhomes”. <strong>Tagore</strong> left for India inSeptember, 1913.The award <strong>of</strong> the Nobel Prizetransformed the reputation <strong>of</strong><strong>Tagore</strong> and he was invited allacross the globe. His ideas <strong>of</strong>internationalism also spurredhis desire to travel and interactwith cultures. In 1916 hevisited Rangoon and Japan,stopping at Kobe, Osaka,Tokyo and Yokohama. <strong>Tagore</strong>was keen to locate in Japan a“manifestation <strong>of</strong> modern lifein the spirit <strong>of</strong> its traditionalpast”, and he was moved by theaesthetic consciousness <strong>of</strong> thepeople. <strong>Tagore</strong> was, however,disappointed by the emergence<strong>of</strong> nationalism and imperialismin the country.In September 1916 <strong>Tagore</strong>was invited to the USA todeliver a series <strong>of</strong> lectures. Hetravelled to Seattle, Chicagoand Philadelphia deliveringhis critique against the cult <strong>of</strong>nationalism. Although he waswarmly received, his viewsgenerated a lot <strong>of</strong> hostility.<strong>Tagore</strong> returned to Europein 1920. In England, he wasdisappointed to find thathis strident stand againstnationalism and war had cooledthe ardour <strong>of</strong> his friends. Hetravelled to France and wasdeeply moved on his trip tothe battle ground near Rheims.At Strasbourg, he delivered hislecture titled “The Message <strong>of</strong>the Forest”. His subsequentvisit to USA to generate fundsfor Visva-Bharati proved to beunsuccessful. Not only did hefail to raise significant funds,he also encountered a distinctlyhostile audience for his criticism<strong>of</strong> materialism and nationalism.In 1921, <strong>Tagore</strong> travelled toParis to meet Romain Rolland,immediately warming to thevision <strong>of</strong> internationalismthat both shared. <strong>Tagore</strong> alsovisited Holland and Belgium,Denmark and Swedendelivering an address at theSwedish academy. He travelledto Germany looking with<strong>Tagore</strong> with dignitaries on a visit to Japan, 1929 <strong>Tagore</strong> addressing people during his visit to Singapore, 1927INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 54 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 55

interest at the Universitiesthere and proceeded to Viennaand Prague. <strong>Tagore</strong>’s poetrywas now being translated anddiscussed all across Europe and<strong>of</strong>fered a significant acceptanceamong a population that hadbeen ravaged by war. Hereceived a rapturous welcomeeverywhere as he spoke aboutpeace and world unity.In 1924, <strong>Tagore</strong> travelled to China.He visited Shanghai, Beijing,Nanking and Chufu. <strong>Tagore</strong>interacted with a number <strong>of</strong>poets, educationists once againreviving the notion <strong>of</strong> an Asiansolidarity. He visited the tomb<strong>of</strong> Confucious and addressedthe Chinese youth on severaloccasions reminding them <strong>of</strong> thetradition <strong>of</strong> cultural exchangebetween China and India.<strong>Tagore</strong>’s visit to South Americatook him to Buenos Aires,Chapadmalal and San Isidro. Anailing Rabindranath recuperatedat the residence <strong>of</strong> VictoriaOcampo (1890-1979). Thevoyage to South America wassignificant for Rabindranath’spreparation <strong>of</strong> the manuscript<strong>of</strong> Purabi with its copiousdoodlings. It was from this pointonwards that <strong>Tagore</strong>’s career asan artist would find expression.In 1926, <strong>Tagore</strong> visited Italyat the invitation <strong>of</strong> Mussolini(1883-1945). He received arapturous reception, but oncehe realized the fascist leanings<strong>of</strong> Italy he severely denouncedthe Italian government. <strong>Tagore</strong>proceeded to Oslo, Belgrade,Bucharest, Athens and Cairo.At Germany he interacted withAlbert Einstein (1879-1955).The translations <strong>of</strong> his poetryensured that he receivedrecognition and appreciationwherever he went.In 1927, <strong>Tagore</strong> undertook atrip to South East Asia, visitingMalaya, Java, Bali, Siam andBurma. The overarching motif<strong>of</strong> this voyage was to study therelics <strong>of</strong> an Indian civilizationand to forge closer cultural tieswith these regions. <strong>Tagore</strong>’stravelogue on this trip shows hiskeen interest in the music anddance <strong>of</strong> this region.In 1930, <strong>Tagore</strong> travelled forthe last time to Europe. On thistrip he exhibited his paintings atseveral cities including Paris andthey were warmly applauded.He travelled to the University<strong>of</strong> Oxford to deliver the Hibbertlectures, later published as TheReligion <strong>of</strong> Man. He travelledA photograph from <strong>Tagore</strong>’s USA visit, 1916<strong>Tagore</strong> with students in Russia, 1930INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 56 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 57

Painting by <strong>Tagore</strong> on board S.S. Tosa Maru, 1929across Munich and reachedRussia. He was warmly greetedby the Russian governmentand intellectuals. <strong>Tagore</strong> wasdeeply impressed by the ruraldevelopment and co-operativemovements here and laterattempted to replicate them inSantiniketan.In 1932 <strong>Tagore</strong> travelledoverseas for the last time toPersia on the invitation <strong>of</strong>the King <strong>of</strong> Iran. He visitedBaghdad, Shiraz, Tehran,Bushehr and he appreciated themodern measures to improvethe state under Reza ShahPehlavi (1919-1980). Onceagain <strong>Tagore</strong> reminded thisaudience <strong>of</strong> the deep culturalbonds shared by the nations. Hevisited the tomb <strong>of</strong> the famouspoet Saadi and interactedwith the King, emphasizingcommunal harmony as a<strong>Tagore</strong> on arrival in Berlin, 1926necessary condition forprogress. The youngerRabindranath had admired thefree spirit <strong>of</strong> the Bedouins in anearlier poem. Having travelledfor a lifetime, he had finally metthe subject <strong>of</strong> his fantasy.<strong>Tagore</strong>’s travels within thecountry are too numerous tocatalogue. He travelled to allparts <strong>of</strong> the country for variouscauses. The last journey toKolkata from Santiniketan in1941 came immediately afterhis stirring address titled Crisisin Civilization where <strong>Tagore</strong>observed the darkening clouds<strong>of</strong> war and destruction gatherover the world. His only hopewas for the saviour who couldredeem mankind.The sheer range <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong>’stravels fascinates us, consideringthe enormous difficulties andhardship he had to encounter.He was always eager t<strong>of</strong>amiliarize himself with othercultures, integrating the bestaspects within his self andhis institution. The youngRabindranath had travelled forpleasure and education. Oncehe was recognized as a worldpoet, he travelled as a voice <strong>of</strong>humanity to a society recoveringfrom war, warning againstthe dangers <strong>of</strong> nationalism,fascism and imperialism.He retained an unflinchingstance despite the hostilitythat he faced. As <strong>Tagore</strong>devoted himself to the growth<strong>of</strong> Visva-Bharati, his travelswere directed to enrichingthe institution by creating aspace where different culturescould coexist harmoniouslyin one nest. Everywhere hewent, he interacted with thebrightest intellects and creativepersonalities debating issues<strong>of</strong> philosophy, politics andaesthetics.Writing to his daughter, <strong>Tagore</strong>once commented, “I feel arestlessness swaying me… Theworld has welcomed me and Itoo shall welcome the world…I go towards the wide road <strong>of</strong>the wayfarer”. As he travelledacross unknown ways dreamingabout a globe without borders,he searched for the self thatwould be at home in the world.◆The author teaches English literatureat Visva-Bharati, and is a specialist onAmerican Literature.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 58 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 59

“Everyone has something specialcalled ‘my religion’… which is hisreligion? The one that lies hiddenin his heart and keeps on creatinghim.”– Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong> (Of Myself, Tr <strong>of</strong><strong>Tagore</strong>’s Atmaparichaya by DevadattaJoardan & Joe Winter, Visva-Bharati, 23)Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>was born in the familyhouse <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Tagore</strong>’s<strong>of</strong> Jorasanko, a centre <strong>of</strong> 19 thcentury Bengal renaissance.When he was born, the Hindurevivalist movement already wasin progress. Raja RammohanRoy had founded the BrahmoSamaj, Pandit Iswar ChandraVidyasagar started his socialreforms from within Hinduismand Sri Ramkrishna Paramhansa(1836-1886) was preaching hisinter-religious understanding.Maharshi Debendranath <strong>Tagore</strong>,father <strong>of</strong> Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>was an ardent follower <strong>of</strong> RajaRammohan Roy, the maker <strong>of</strong>modern India. Debendranathabjured idolatory, acceptedinitiation into Brahmo Dharma,<strong>Tagore</strong>’s ReligionSABUJKOLI SENRabindranath’s mission is – the divinization <strong>of</strong> man and thehumanizing <strong>of</strong> God. <strong>Tagore</strong>’s journey to “Religion <strong>of</strong> Man” startedwith the shlokas <strong>of</strong> Upanisad in his childhood. It was enrichedby the philosophy <strong>of</strong> the Gita, the teaching <strong>of</strong> the Buddha, theMahavira and also by the Christian tradition besides the indigenousBaul and Sufi traditions.gave it a shape, and becamethe leader <strong>of</strong> a re-orientedfaith founded on the puremonotheism <strong>of</strong> the ancientUpanisads. Every morning hissons had to recite, with correctpronunciation and accent theverses culled from the Vedasand Upanisads. The daily recital<strong>of</strong> these beautiful as well asmorally uplifting verses and thesimple prayer introduced bythe Maharshi influenced youngRabindranath and made alasting impression on his mentalmake up.As a member <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong>’s familyin 1884 at the age <strong>of</strong> twentythree <strong>Tagore</strong> had to take chargeas the Secretary <strong>of</strong> Adi BrahmoSamaj. During this time BrahmoSamaj was the target <strong>of</strong> adverseHindu criticism. As a reactionto Brahmo Dharma a group<strong>of</strong> Hindu educated men wasformed. They called themselvespositivists or atheists. AkshayKumar Dutta (1820-1886)was one <strong>of</strong> them. TheHindu revivalist Pt. SasadharTarkachuramani (1851-1928)invented a new religion calledScientific Hindu Religion. Itstwo organs, Navajivan andPrachar systemically publishedarticles against Brahmo Religion.Bankim Chandra Chattapadhyaythe famous Bengali novelistused to write articles in thesepapers supporting Hinduism.The young Secretary <strong>of</strong> BrahmoSamaj, Rabindranath, took upthe challenge <strong>of</strong> the Hindusand replied to the articles <strong>of</strong>Bankim Chandra. BankimChandra replied back and thewordy duel <strong>of</strong> these two famouslitterateurs continued for sometime. In the long run both <strong>of</strong>them forgave each other andfriendship was establishedbetween them. It will beinteresting to mention here thatthe date Feb.26, 1891 was fixedfor the census in India. SomeBrahmo sects used to thinkthemselves different from theHindus. But the Adi BrahmoSamaj sect <strong>of</strong> Brahmo Dharmato which <strong>Tagore</strong> belongedconsidered themselves as aspecial branch <strong>of</strong> Hinduism.In a letter to C. J. O’Donnell(1850-1934), in charge <strong>of</strong>census, <strong>Tagore</strong> requested him torefer the Adi Brahmo Samaj as‘Theistic Hindu’. He publisheda circular in Tattvabodhinirequesting Adi Bramho familiesto classify themselves as“Hindu – Brahmo” (Rabi Jivani,Prasanta Kumar Pal, AnandaPublisher, Kolkata, Vol.III,165).As a Brahmo, Rabindranathwas against the practice <strong>of</strong>idolatory in Hinduism. He wasagainst the ‘Incarnation-theory’or avatarvada <strong>of</strong> Hinduism.The taboos and prohibitions <strong>of</strong>Hinduism were repugnant tothe poet. In Dharmer Adhikar(Vide Sanchaya, RabindraRachanavali, Vol. XII). He says :“There are two sides <strong>of</strong> man’spower. One is his ‘can’ and theother is his ‘should’. The mancan do certain actions, this is theeasy side <strong>of</strong> his power. But heshould do certain actions, thisconstitutes the utmost exercise<strong>of</strong> his power. Religion stands onthe <strong>high</strong> precipice <strong>of</strong> the ‘should’and as such, always draws the‘can’ towards it. When our ‘can’is completely assimilated by our‘should’, we attain the most desiredobject <strong>of</strong> our life, we attain Truth.But these impotent people who cannot act up to this ideal <strong>of</strong> religion,try to pull it down to their own level.Thus taboos and prohibitions arise”.Rabindranath did not spareany opportunity to protestvehemently against orthodoxRaja Rammohan RoyHinduism be that through hisliterary works or through hisletters to Hemanta Bala Devi(1894-1976) or Kadambini Devi(1878-1943). But Rabindranathhad an unprejudiced mind anddid not subscribe to the views<strong>of</strong> any particular conventionalreligion. We have an idea <strong>of</strong>his religious view from thefollowing statement “I havebeen asked to let you knowsomething about my own view<strong>of</strong> religion. One <strong>of</strong> the reasonswhy I always feel reluctant tospeak about this is that I havenot come to my own religionthrough the portals <strong>of</strong> passiveacceptance <strong>of</strong> a particular creedowing to some accident <strong>of</strong> birth.I was born in a family whowere pioneers in the revival inour country <strong>of</strong> a great religion,based upon the utterance <strong>of</strong>Indian sages in the Upanisads.But owing to my idiosyncrasy <strong>of</strong>temperament, it was impossiblefor me to accept any religiousteaching on the only groundthat people in my surroundingsbelieved it to be true… Thusmy mind was brought up inan atmosphere <strong>of</strong> freedom,freedom from the dominance <strong>of</strong>any creed that had its sanctionin the definite authority <strong>of</strong> somescripture or in the teaching <strong>of</strong>some organized worshippers(Lectures And Addresses,R.N. <strong>Tagore</strong>, Macmillan & Co.Ltd., London, 11).Throughout his lifeRabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong> neverclung to one belief, however,his thoughts went throughchanges and developed further.From the fiftieth year <strong>of</strong> hislife we find a change in hisideas about religion. He wasno longer against Hinduism.He was eager to incorporatethe best <strong>of</strong> Hinduism intoBrahmoism. At that time therewas a debate in the country:Are the Brahmos Hindus? TheBrahmo leaders were dividedon this issue. According tosome, Brahmos are separatefrom the Hindus like Christiansand Muslims. But as we havealready mentioned earlieraccording to <strong>Tagore</strong> Brahmoswere Hindus and in support<strong>of</strong> this view, he read a paperin the Sadharan BrahmoSamaj Mandir under thecaption Atmaparichaya. Hesaid: “Brahmoism has receivedits spiritual inspiration fromHindus, it stands on theINDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 60 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 61

oad basis <strong>of</strong> Hindu culture.Brahmoism has a universaloutlook but it is always thereligion <strong>of</strong> the Hindus. Wehave thought and assimilatedit by the help <strong>of</strong> the Hindumind. Today Hinduism mustopen the sacred, secret truth <strong>of</strong>its own heart. It must preachthe gospel <strong>of</strong> universalismto the entire universe. Todaythrough the salvation <strong>of</strong>Brahmoism, Hinduism hasbeen fulfilling its own mission(from Atmaparichaya, inTattvabodhini Patrika, 1919).<strong>Tagore</strong>’s unique ideas aboutreligion began to take shapefrom this time. What hebelieved was neither Hinduismnor Brahmoism but a synthesisbetween the two. He didnot discard the old orthodoxreligion totally, and yet at thesame time he did not acceptBrahmo religion with thesame enthusiasm as before.Brahmoism could not satisfyhim any more. He had seenthat Brahmoism also hadbecome conventional and rigidlike Hinduism. Brahmoism <strong>of</strong>Rammohan Roy, the aim <strong>of</strong>which was to unite peoplefailed to serve its purpose.Brahmos also used to think <strong>of</strong>non-Brahmos specially Hindusas opposed to themselves. Fromthis time we see <strong>Tagore</strong> wasnot confined to any particularreligion and sect. His novel‘Gora’ published in 1910 depictsthe condition <strong>of</strong> the society.There is staunch BrahmoHaranbabu, ritualistic HinduHarimohini and characters likePareshbabu and Anandamayeewho believed in the “religion<strong>of</strong> man”. The central character<strong>Tagore</strong> in Nara, Japan, 1916<strong>of</strong> the novel ‘Gora’ initially wasa staunch Hindu. He was veryparticular to observe Hindurituals. However, when he cameto know <strong>of</strong> his Irish birth andChristian origin, his previousYoung <strong>Tagore</strong> with father Maharshi Debendranath – a painting by Gaganendranath <strong>Tagore</strong>notions were shattered. Whenhe saw Anandamayee, whobeing a Brahmin Hindu ladytook the orphan infant Gorain her lap – unthinkable atthat time, Gora declared thathe was free then. He has noreligion, no caste, no creed, nobondage <strong>of</strong> doctrines. He wakesup to a new awareness <strong>of</strong> hisidentity. He is a human being,neither Hindu nor Christian.Then he was able to realize hisuniversality. From ‘Gora’ wefind a seed <strong>of</strong> ‘The religion <strong>of</strong>man’ in <strong>Tagore</strong>. Pr<strong>of</strong>essor AsinDasgupta rightly observed thatthere is no doubt Rabindranathspoke through Pareshbabu’smouth and Anandamayee’swork (Vide Rabi Thakurs Party,Asin Dasgupta, Visva-BharatiQuarterly, New Series, Vol. IV,Nos. I & II).The years 1910 & 1911 arevery important to understand<strong>Tagore</strong>’s views on religion. In1910 “Christotsava” (celebration<strong>of</strong> Jesus’ Birthday) was firstobserved in Santiniketan’sprayer hall. On <strong>Tagore</strong>’s requestHemlata Devi, wife <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong>’snephew Dwipendranath <strong>Tagore</strong>translated a book on Sufism, thefirst issue <strong>of</strong> this was publishedin Tattvabodhini Patrika in1911. In Tattvabodhini in thesame year <strong>Tagore</strong> published“Bouddhadharme Bhaktivada”(Devotion in Buddhism).Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong> wasvery much interested in thetranslation <strong>of</strong> the great Sufipoet, Kabir (1440-1518). Hewas the inspiration behindPandit Ksitimohan Sen Sastri’s(1880-1960) translation <strong>of</strong>Kabir’s Doha. It is evident thatRabindranath wanted to cull thebest <strong>of</strong> all religions and formedhis own view in the mannerin which honey is formed in aflower.<strong>Tagore</strong>’s journey to “Religion <strong>of</strong>Man” started with the slokas <strong>of</strong>INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 62 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 63

Upanisad in his childhood. Itwas enriched by the philosophy<strong>of</strong> the Gita (though he didnot like the context <strong>of</strong> theGita, i.e., the warfield andalso he was against the idea <strong>of</strong>arguments in favour <strong>of</strong> war),different schools <strong>of</strong> Vedantaand the philosophy <strong>of</strong> medievalsaints. Vedanta was his naturalinheritance but like his fatherDebendranath, Rabindranathdid not accept entirely theAdvaitic interpretation. “Brahmasatya jagat mithya” wasnever acceptable to him. LikeDebendranath he also had areverence for the world. He saidsalvation through the practice<strong>of</strong> renunciation was not forhim. He wanted to taste thefreedom <strong>of</strong> joy in the midst <strong>of</strong><strong>Tagore</strong> at the Santiniketan Templeinnumerable ties. What attractedhim was Vaisnavism, speciallythe Visistadvaita <strong>of</strong> Ramanuja(1017-1137). Vaisnavism,the cult <strong>of</strong> the deity and thedevotee, the love between thetwo attracted him. Rabindranathreceived the inner significance<strong>of</strong> creation and love from themedieval Bengali VaisnavaPadavali (lyrics). The Vaisnavaconcept <strong>of</strong> beauty is imbibedby the poet, as beauty and loveform the keynote <strong>of</strong> <strong>Tagore</strong>’swritings.Rabindranath’s mission is – thedivinization <strong>of</strong> man and thehumanizing <strong>of</strong> God. <strong>Tagore</strong>was influenced by Buddhismalso. Buddhist philosophy<strong>of</strong> Pratityasamutpada orKsanikatvavada did not attracthim, neither he was attractedby the Buddhist concept <strong>of</strong>Nirvana where there is nopain or pleasure. He wasattracted to Buddhist concept<strong>of</strong> Ahimsa. He was fascinatedby the Buddhist’s teachings <strong>of</strong>Maitri (brotherhood), Mudita(happiness in everything),Upeksa (indifference) andKaruna (compassion).Rabindranath was attracted towhatever was humane. Theperson Buddha was near to<strong>Tagore</strong>’s heart. Rabindranath’sview on Buddha will betransparent from his saying“This wisdom came, neitherin texts <strong>of</strong> scripture, nor insymbols <strong>of</strong> deities, nor inreligious practices sanctified byages, but through the voice <strong>of</strong>a living man and the love thatflowed from a human heart”(Creative Unity, Rabindranath<strong>Tagore</strong>, Macmillan India Ltd.,1922, 69).<strong>Tagore</strong> was also influencedby the Baul tradition. Baulis a non-orthodox faith thatflourished in Bengal. The Baulphilosophy is very similar toSufi philosophy. The simple lifestyle <strong>of</strong> Baul singers wanderingaround singing and dancing –always absorbed in the joy <strong>of</strong>life touched <strong>Tagore</strong>. The Baulsbelieved that there is God inevery man’s heart and He maybe realized only by sincerelove and devotion. There is noroom for distinction <strong>of</strong> casteand sex. At Silaidaha (<strong>Tagore</strong>’sfamily estate) <strong>Tagore</strong> cameinto contact with Baul GaganHarkara, Fakir Fikirchand(1833-1896) and Suna-ullah. In<strong>Tagore</strong> with people at Silaidaha (his family estate)Santiniketan he came to knowNabani Das Baul. <strong>Tagore</strong> wasalso acquainted with LalanFakir’s songs though there is noevidence <strong>of</strong> their meeting. Thesongs <strong>of</strong> Bauls had such impactupon Rabindranath that hisnovel Gora starts with a Baulsong. In his book ‘The Religion<strong>of</strong> Man’ (Hibbert Lecture,Oxford, 1930) he quoted anumber <strong>of</strong> Baul songs and hecomposed many songs in theBaul tune, in keeping with theBaul spirit, such as:O my mind,You did not wake up when theman <strong>of</strong> your heartCame to your door.You woke up in the darkAt the sound <strong>of</strong> his departingfootstepsMy lonely night passes on a maton the floor.His flute sounds in darkness,Alas, I can not see Him.[Tr. cited from “The Spirituality <strong>of</strong>Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>”, by Sitanshu SekharChakravarty, in The Spirituality <strong>of</strong> ModernHinduism, 274]Here the relation between thesinger and the God – “the man<strong>of</strong> the heart” – is very intimate.Sometimes <strong>Tagore</strong> calls this “man<strong>of</strong> the heart” the “Eternal Friend”,sometimes he calls him ‘lover’.This ‘lover’ is <strong>Tagore</strong>’s JivanDevata, the ‘Lord <strong>of</strong> Life’, theguiding principle <strong>of</strong> his life. ThisJivan Devata sometimes appearsto him as male, sometimes asfemale. Like the Bauls, he wasalso looking out for this “man <strong>of</strong>heart”.◆The author teaches Philosophy and Religionat Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 64 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 65

Gandhi and <strong>Tagore</strong>AMARTYA SENRabindranath knew that he could not have given India thepolitical leadership that Gandhi provided, and he was neverstingy in his praise for what Gandhi did for the nation.And yet each remained deeply critical <strong>of</strong> many things thatthe other stood for.<strong>Tagore</strong> and Gandhi – a painting by Jamini RoySince Rabindranath <strong>Tagore</strong>and Mohandas Gandhiwere two leading Indianthinkers in the twentieth century,many commentators havetried to compare their ideas.On learning <strong>of</strong> Rabindranath’sdeath, Jawaharlal Nehru, thenincarcerated in a British jail inIndia, wrote in his prison diaryfor August 7, 1941:“Gandhi and <strong>Tagore</strong>. Two typesentirely different from each other,and yet both <strong>of</strong> them typical <strong>of</strong>India, both in the long line <strong>of</strong>India’s great men ... It is not somuch because <strong>of</strong> any single virtuebut because <strong>of</strong> the tout ensemble,that I felt that among the world’sgreat men today Gandhi and<strong>Tagore</strong> were supreme as humanbeings. What good fortune for meto have come into close contactwith them.”Romain Rolland (1866-1944)was fascinated by the contrastbetween them, and whenhe completed his book onGandhi, he wrote to an Indianacademic, in March 1923: “I havefinished my Gandhi, in whichI pay tribute to your two greatriver-like souls, overflowingwith divine spirit, <strong>Tagore</strong>and Gandhi.” The followingmonth, he recorded in his diaryan account <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> thedifferences between Gandhiand <strong>Tagore</strong> written by ReverendC.F. Andrews (1871-1940), theEnglish clergyman and publicactivist who was a close friend<strong>of</strong> both men (and whoseimportant role in Gandhi’s lifein South Africa as well as Indiais well portrayed in RichardAttenborough’s film Gandhi[1982]). Andrews described toRolland a discussion between<strong>Tagore</strong> and Gandhi, at whichhe was present, on subjects thatdivided them:“The first subject <strong>of</strong> discussionwas idols; Gandhi defended them,believing the masses incapable <strong>of</strong>raising themselves immediately toabstract ideas. <strong>Tagore</strong> cannot bearto see the people eternally treatedas a child. Gandhi quoted the greatthings achieved in Europe by theflag as an idol; <strong>Tagore</strong> found iteasy to object, but Gandhi held hisground, contrasting European flagsbearing eagles, etc., with his own,on which he has put a spinningwheel. The second point <strong>of</strong>discussion was nationalism, whichGandhi defended. He said that onemust go through nationalism toreach internationalism, in the sameway that one must go through warto reach peace.”INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 66 INDIA PERSPECTIVES VOL 24 NO. 2/2010 67