HRSA Service Category Title - Harris County's New Web Site!

HRSA Service Category Title - Harris County's New Web Site!

HRSA Service Category Title - Harris County's New Web Site!

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

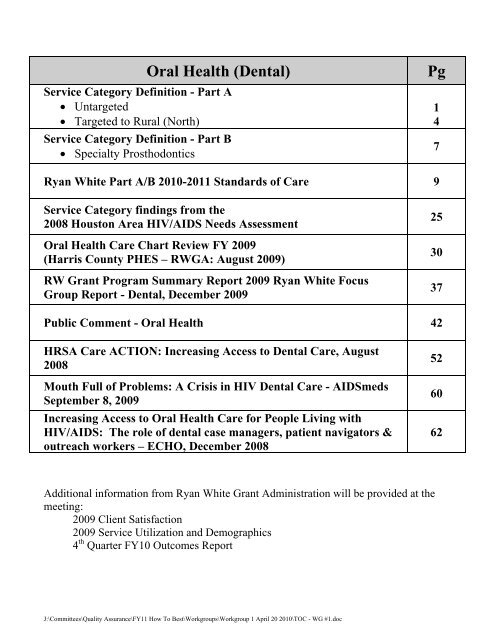

<strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Definition - Part A<br />

� Untargeted<br />

� Targeted to Rural (North)<br />

<strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Definition - Part B<br />

� Specialty Prosthodontics<br />

Oral Health (Dental) Pg<br />

Ryan White Part A/B 2010-2011 Standards of Care 9<br />

<strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> findings from the<br />

2008 Houston Area HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment<br />

Oral Health Care Chart Review FY 2009<br />

(<strong>Harris</strong> County PHES – RWGA: August 2009)<br />

RW Grant Program Summary Report 2009 Ryan White Focus<br />

Group Report - Dental, December 2009<br />

Public Comment - Oral Health 42<br />

<strong>HRSA</strong> Care ACTION: Increasing Access to Dental Care, August<br />

2008<br />

Mouth Full of Problems: A Crisis in HIV Dental Care - AIDSmeds<br />

September 8, 2009<br />

Increasing Access to Oral Health Care for People Living with<br />

HIV/AIDS: The role of dental case managers, patient navigators &<br />

outreach workers – ECHO, December 2008<br />

Additional information from Ryan White Grant Administration will be provided at the<br />

meeting:<br />

2009 Client Satisfaction<br />

2009 <strong>Service</strong> Utilization and Demographics<br />

4 th Quarter FY10 Outcomes Report<br />

J:\Committees\Quality Assurance\FY11 How To Best\Workgroups\Workgroup 1 April 20 2010\TOC - WG #1.doc<br />

1<br />

4<br />

7<br />

25<br />

30<br />

37<br />

52<br />

60<br />

62

<strong>HRSA</strong> <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong><br />

<strong>Title</strong>: (RWGA only)<br />

Local <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong><br />

<strong>Title</strong>:<br />

Budget Type:<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

Budget Requirements or<br />

Restrictions:<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

<strong>HRSA</strong> <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong><br />

Definition:<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

Local <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong><br />

Definition:<br />

Target Population (age,<br />

gender, geographic, race,<br />

ethnicity, etc.):<br />

Oral Health<br />

Oral Health<br />

Unit Cost<br />

Not Applicable<br />

Oral health care includes diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic<br />

services provided by general dental practitioners, dental specialists,<br />

dental hygienists and auxiliaries, and other trained primary care<br />

providers.<br />

Restorative dental services, oral surgery, root canal therapy, fixed<br />

and removable prosthodontics; periodontal services includes<br />

subgingival scaling, gingival curettage, osseous surgery,<br />

gingivectomy, provisional splinting, laser procedures and<br />

maintenance. Oral medication (including pain control) for HIV<br />

patients 15 years old or older must be based on a comprehensive<br />

individual treatment plan.<br />

HIV/AIDS infected individuals residing within the Houston Eligible<br />

Metropolitan Area (EMA).<br />

<strong>Service</strong>s to be Provided: <strong>Service</strong>s must include, but are not limited to: individual<br />

comprehensive treatment plan; diagnosis and treatment of HIVrelated<br />

oral pathology, including oral Kaposi’s Sarcoma, CMV<br />

ulceration, hairy leukoplakia, xerostomia, lichen planus, aphthous<br />

ulcers and herpetic lesions; diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis;<br />

standard preventive procedures, including oral hygiene instruction,<br />

diet counseling and home care program; oral prophylaxis;<br />

restorative care; oral surgery including dental implants; root canal<br />

therapy; fixed and removable prosthodontics including crowns and<br />

bridges; periodontal services, including subgingival scaling, gingival<br />

curettage, osseous surgery, gingivectomy, provisional splinting,<br />

laser procedures and maintenance. Proposer must have mechanism<br />

in place to provide oral pain medication as prescribed for clients by<br />

<strong>Service</strong> Unit Definition(s):<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

FY 2011 Oral Health: Untargeted – Part A<br />

DRAFT (as of 03-23-10)<br />

the dentist.<br />

A unit of service is defined as one (1) dental visit which includes<br />

restorative dental services, oral surgery, root canal therapy, fixed<br />

and removable prosthodontics; periodontal services includes<br />

subgingival scaling, gingival curettage, osseous surgery,<br />

gingivectomy, provisional splinting, laser procedures and<br />

maintenance. Oral medication (including pain control) for HIV<br />

patients 15 years old or older must be based on a comprehensive<br />

individual treatment plan.<br />

Financial Eligibility: Refer to the RWPC’s approved Financial Eligibility for Houston<br />

Page 1 of 72

EMA <strong>Service</strong>s.<br />

Client Eligibility: HIV-infected adults residing in the Houston EMA meeting financial<br />

eligibility criteria.<br />

Agency Requirements: Agency must document that the primary patient care dentist has 2<br />

years prior experience treating HIV disease and/or on-going HIV<br />

educational programs that are documented in personnel files and<br />

updated regularly.<br />

Staff Requirements: State of Texas dental license; licensed dental hygienist and state<br />

Special Requirements:<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

FY 2011 Oral Health: Untargeted – Part A<br />

DRAFT (as of 03-23-10)<br />

radiology certification for dental assistants.<br />

None.<br />

Page 2 of 72

FY 2011 Oral Health: Untargeted – Part A<br />

DRAFT (as of 03-23-10)<br />

FY 2011 RWPC “How to Best Meet the Need” Decision Process<br />

Step in Process: Council<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: Steering Committee<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: Quality Assurance Committee<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: HTBMTN Workgroup<br />

Recommendations: Financial Eligibility:<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

Page 3 of 72

FY 2011 Oral Health: Rural (North) – Part A<br />

DRAFT (as of 03-23-10)<br />

<strong>HRSA</strong> <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Oral Health<br />

<strong>Title</strong>: (RWGA only)<br />

Local <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Oral Health – Rural (North)<br />

<strong>Title</strong>:<br />

Budget Type:<br />

Unit Cost<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

Budget Requirements or Not Applicable<br />

Restrictions:<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

<strong>HRSA</strong> <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Oral health care includes diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic<br />

Definition:<br />

services provided by general dental practitioners, dental specialists,<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

dental hygienists and auxiliaries, and other trained primary care<br />

providers.<br />

Local <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Restorative dental services, oral surgery, root canal therapy, fixed<br />

Definition:<br />

and removable prosthodontics; periodontal services includes<br />

subgingival scaling, gingival curettage, osseous surgery,<br />

gingivectomy, provisional splinting, laser procedures and<br />

maintenance. Oral medication (including pain control) for HIV<br />

patients 15 years old or older must be based on a comprehensive<br />

individual treatment plan. Prosthodontics services to HIV-infected<br />

individuals including, but not limited to examinations and diagnosis<br />

of need for dentures, diagnostic measurements, laboratory services,<br />

tooth extractions, relines and denture repairs.<br />

Target Population (age, HIV/AIDS infected individuals residing in Houston Eligible<br />

gender, geographic, race, Metropolitan Area (EMA) or Health <strong>Service</strong> Delivery Area (HSDA)<br />

ethnicity, etc.):<br />

counties other than <strong>Harris</strong> County. Comprehensive Oral Health<br />

services targeted to individuals residing in the northern counties of<br />

the EMA/HSDA, including Waller, Walker, Montgomery, Austin,<br />

Chambers and Liberty Counties.<br />

<strong>Service</strong>s to be Provided: <strong>Service</strong>s must include, but are not limited to: individual<br />

comprehensive treatment plan; diagnosis and treatment of HIVrelated<br />

oral pathology, including oral Kaposi’s Sarcoma, CMV<br />

ulceration, hairy leukoplakia, xerostomia, lichen planus, aphthous<br />

ulcers and herpetic lesions; diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis;<br />

standard preventive procedures, including oral hygiene instruction,<br />

diet counseling and home care program; oral prophylaxis;<br />

restorative care; oral surgery including dental implants; root canal<br />

therapy; fixed and removable prosthodontics including crowns,<br />

bridges and implants;<br />

periodontal services, including subgingival<br />

scaling, gingival curettage, osseous surgery, gingivectomy,<br />

provisional splinting, laser procedures and maintenance. Proposer<br />

must have mechanism in place to provide oral pain medication as<br />

prescribed for clients by the dentist.<br />

<strong>Service</strong> Unit Definition(s): General Dentistry: A unit of service is defined as one (1) dental<br />

(RWGA/TRG only) visit which includes restorative dental services, oral surgery, root<br />

canal therapy, fixed and removable prosthodontics; periodontal<br />

Page 4 of 72

Financial Eligibility:<br />

Client Eligibility:<br />

Agency Requirements:<br />

Staff Requirements:<br />

Special Requirements:<br />

(RWGA only)<br />

FY 2011 Oral Health: Rural (North) – Part A<br />

DRAFT (as of 03-23-10)<br />

services includes subgingival scaling, gingival curettage, osseous<br />

surgery, gingivectomy, provisional splinting, laser procedures and<br />

maintenance. Oral medication (including pain control) for HIV<br />

patients 15 years old or older must be based on a comprehensive<br />

individual treatment plan.<br />

Prosthodontics: A unit of services is defined as one (1)<br />

Prosthodontics visit.<br />

Refer to the RWPC’s approved Financial Eligibility for Houston<br />

EMA/HSDA <strong>Service</strong>s.<br />

HIV-infected adults residing in the rural area of Houston<br />

EMA/HSDA meeting financial eligibility criteria.<br />

Agency must document that the primary patient care dentist has 2<br />

years prior experience treating HIV disease and/or on-going HIV<br />

educational programs that are documented in personnel files and<br />

updated regularly.<br />

<strong>Service</strong> delivery site must be located in one of the northern counties<br />

of the EMA/HSDA area: Waller, Walker, Montgomery, Austin,<br />

Chambers or Liberty Counties<br />

State of Texas dental license; licensed dental hygienist and state<br />

radiology certification for dental assistants.<br />

Must comply with the joint Part A/B standards of care where<br />

applicable.<br />

Page 5 of 72

FY 2011 Oral Health: Rural (North) – Part A<br />

DRAFT (as of 03-23-10)<br />

FY 2011 RWPC “How to Best Meet the Need” Decision Process<br />

Step in Process: Council<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: Steering Committee<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: Quality Assurance Committee<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: HTBMTN Workgroup<br />

Recommendations: Financial Eligibility:<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

Page 6 of 72

<strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Definition - Ryan White Part B Grant<br />

April 1, 2010 - March 31, 2011<br />

Local <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong> Oral Health Care – Specialty Prosthodontics (13)<br />

Amount Available<br />

Unit Cost:<br />

To be determined<br />

Budget Requirements or Maximum of 10% of budget for Administrative Costs<br />

Restrictions:<br />

Local <strong>Service</strong> <strong>Category</strong><br />

Definition:<br />

Target Population (age,<br />

gender, geographic, race,<br />

ethnicity, etc.):<br />

Prosthodontics services to HIV infected individuals including but<br />

not limited to examinations and diagnosis of need for dentures,<br />

crowns, bridgework and implants, diagnostic measurements,<br />

laboratory services, tooth extraction, relines and denture repairs.<br />

General dentistry may be provided only if additional unallocated<br />

funds are added to the category during the year.<br />

HIV/AIDS infected individuals residing within the Houston HIV<br />

<strong>Service</strong> Delivery Area (HSDA).<br />

<strong>Service</strong>s to be Provided: <strong>Service</strong>s must include, but are not limited to: fixed and removable<br />

prosthodontics including crowns, bridges and implants.<br />

<strong>Service</strong> Unit Definition(s): A unit of service is defined as one (1) prosthodontics visit.<br />

Financial Eligibility: Income at or below 300% Federal Poverty Guidelines.<br />

Client Eligibility: HIV positive; Adult resident of Houston HSDA<br />

Agency Requirements: Agency must document that the primary patient care dentist has 2<br />

years prior experience treating HIV disease and/or on-going HIV<br />

educational programs that are documented in personnel files and<br />

updated regularly. Dental facility and appropriate dental staff must<br />

maintain Texas licensure/certification and follow all applicable<br />

OSHA requirements for patient management and laboratory<br />

protocol.<br />

Providers and system must be Medicaid/Medicare certified to ensure<br />

that Ryan White funds are the payer of last resort.<br />

Staff Requirements: State dental license.<br />

Special Requirements: Must comply with the Joint Part A/B Standards of care where<br />

applicable.<br />

J:\Committees\Quality Assurance\FY 11 <strong>Service</strong> Definitions - Part B & SS\2011 Svc Cat Defs - Pt B 04-09-2010.doc<br />

Page 7 of 72

������������������������������������������������������<br />

FY 2011 RWPC “How to Best Meet the Need” Decision Process<br />

Step in Process: Council<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: Steering Committee<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: Quality Assurance Committee<br />

Recommendations: Approved: Y_____ No: ______<br />

Approved With Changes:______<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Step in Process: HTBMTN Workgroup<br />

Recommendations: Financial Eligibility:<br />

1.<br />

2.<br />

3.<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

If approved with changes list<br />

changes below:<br />

Date:<br />

Page 8 of 72

2010-2011 HOUSTON ELIGIBLE METROPOLITAN AREA: RYAN WHITE CARE<br />

ACT PART A/B<br />

STANDARDS OF CARE FOR HIV SERVICES<br />

RYAN WHITE GRANT ADMINISTRATION SECTION<br />

HARRIS COUNTY PUBLIC HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES (HCPHES)<br />

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..10<br />

General Standards…………………………………………………………………………….........11<br />

<strong>Service</strong> Specific Standards…………………………………………………………………......... 21<br />

Page 9 of 72

INTRODUCTION<br />

According to the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization (JCAHO) 2008) 1<br />

, a<br />

standard is a “statement that defines performance expectations structures, or processes that must be in<br />

place for an organization to provide safe, high-quality care, treatment, and services”. Standards are<br />

developed by subject experts and are usually the minimal acceptable level of quality in service delivery.<br />

The Houston EMA Ryan White Grant Administration (RWGA) Standards of Care (SOCs) are based on<br />

multiple sources including RWGA on-site program monitoring results, consumer input, the US Public<br />

Health <strong>Service</strong>s guidelines, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Conditions of Participation (COP) for<br />

health care facilities, JCAHO accreditation standards, the Texas Administrative Code, Center for<br />

Substance Abuse and Treatment (CSAT) guidelines and other federal, state and local regulations.<br />

Purpose<br />

The purpose of the Ryan White Part A/B SOCs is to determine the minimal acceptable levels of quality in<br />

service delivery and to provide a measurement of the effectiveness of services.<br />

Scope<br />

The Houston EMA SOCs apply to Part A, Part B and State <strong>Service</strong>s, funded <strong>HRSA</strong> defined core and<br />

support services including the following services in FY 2009/10:<br />

• Primary Medical Care<br />

• Vision Care<br />

• Medical Case Management<br />

• Clinical Case Management<br />

• Local AIDS Pharmaceutical<br />

Assistance Program (LPAP)<br />

• Oral Health<br />

• Health insurance<br />

• Hospice Care<br />

• Mental Health <strong>Service</strong>s<br />

• Substance Abuse services<br />

• Home & Community Based <strong>Service</strong>s (Facility-Based)<br />

• Early Intervention <strong>Service</strong>s<br />

• Legal <strong>Service</strong>s<br />

• Medical Nutrition Therapy<br />

• Non-Medical Case Management (<strong>Service</strong> Linkage)<br />

• Food Bank<br />

• Transportation<br />

• Rehabilitation <strong>Service</strong>s<br />

• Linguistic <strong>Service</strong>s<br />

Standards Development<br />

The first group of standards was developed in 1999 following <strong>HRSA</strong> requirements for sub grantees to<br />

implement monitoring systems to ensure subcontractors complied with contract requirements.<br />

Subsequently, the RWGA facilitates annual work group meetings to review the standards and to make<br />

applicable changes. Workgroup participants include physicians, nurses, case managers and executive staff<br />

from subcontractor agencies as well as consumers.<br />

Organization of the SOCs<br />

The standards cover all aspect of service delivery for all funded service categories. Some standards are<br />

consistent across all service categories and therefore are classified under general standards.<br />

These include:<br />

• Staff requirements, training and supervision<br />

• Client rights and confidentiality<br />

• Agency and staff licensure<br />

• Emergency Management<br />

The RWGA funds three case management models. Unique requirements for all three case management<br />

service categories have been classified under <strong>Service</strong> Specific SOCs “Case Management (All <strong>Service</strong><br />

Categories)”. Specific service requirements have been discussed under each service category.<br />

1<br />

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization (2008). Comprehensive accreditation manual<br />

for ambulatory care; Glossary<br />

Page 10 of 72

GENERAL STANDARDS<br />

1.0 Staff Requirements<br />

1.1 Staff Screening (Pre-Employment)<br />

Staff providing services to clients shall be screened for<br />

appropriateness by provider agency as follows:<br />

• Personal/Professional references<br />

• Personal interview<br />

• Written application<br />

Criminal background checks, if required by Agency Policy,<br />

must be conducted prior to employment and thereafter for all<br />

staff and/or volunteers per Agency policy.<br />

1.2 Initial Training: Staff/Volunteers<br />

Initial training includes eight (8) hours HIV/AIDS basics<br />

(including one (1) hour HIV/mental health co-morbidity<br />

sensitivity training), safety issues (fire & emergency<br />

preparedness, hazard communication, infection control,<br />

universal precautions), confidentiality issues, role of<br />

staff/volunteers, agency-specific information (e.g. Drug Free<br />

Workplace policy). Initial training must be completed within<br />

60 days of hire.<br />

1.3<br />

Standard Measure<br />

Staff Performance Evaluation<br />

Agency will perform annual staff performance evaluation<br />

1.4 Cultural and HIV Mental Health Co-morbidity Competence<br />

Training/Staff and Volunteers<br />

All staff must receive four (4) hours of cultural competency<br />

training and one (1) hour of HIV/Mental Health co-morbidity<br />

sensitivity training annually.<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Review of personnel and/or volunteer files indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Documentation of all training in personnel file.<br />

• Specific training requirements are specified in Agency Policy<br />

and Procedure<br />

• Materials for staff training and continuing education are on<br />

file<br />

• Staff interviews indicate compliance<br />

• Completed annual performance evaluation kept in employee’s<br />

file<br />

• Documentation of training is maintained by the agency in the<br />

personnel file<br />

2.0 <strong>Service</strong>s utilize effective management practices such as cost effectiveness, human resources and quality improvement.<br />

2.1 <strong>Service</strong> Evaluation<br />

Agency has a process in place for the evaluation of client<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

Page 11 of 72

services. • Staff interviews indicate compliance.<br />

2.2 Subcontractor Monitoring<br />

Agency that utilizes a subcontractor in delivery of service,<br />

must have established policies and procedures on<br />

subcontractor monitoring that include:<br />

• Fiscal monitoring<br />

• Program<br />

• Quality of care<br />

• Compliance with guidelines and standards<br />

2.3 Staff Guidelines<br />

Agency develops written guidelines for staff, which include,<br />

at a minimum, agency-specific policies and procedures (staff<br />

selection, resignation and termination process, job<br />

descriptions); client confidentiality; health and safety<br />

requirements; complaint and grievance procedures;<br />

emergency procedures; and statement of client rights.<br />

2.4 Work Conditions<br />

Staff/volunteers have the necessary tools, supplies,<br />

equipment and space to accomplish their work.<br />

2.5<br />

Staff Supervision<br />

Staff services are supervised by a paid coordinator or<br />

manager.<br />

2.6 Professional Behavior<br />

Staffs comply with written standards of professional<br />

behavior.<br />

2.7 Communication<br />

There are procedures in place regarding regular<br />

communication with staff about the program and general<br />

agency issues.<br />

• Documentation of subcontractor monitoring<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Personnel file contains a signed statement acknowledging<br />

that staff guidelines were reviewed and that the employee<br />

understands agency policies and procedures<br />

• Inspection of tools and/or equipment indicates that these are<br />

in good working order and in sufficient supply<br />

• Staff interviews indicate compliance<br />

• Review of personnel files indicates compliance<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Staff guidelines include standards of professional behavior<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Review of personnel files indicates compliance<br />

• Review of agency’s complaint and grievance files<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Documentation of regular staff meetings<br />

• Staff interviews indicate compliance<br />

Page 12 of 72

2.8<br />

2.9<br />

Accountability<br />

There is a system in place to document staff work time.<br />

Staff Availability<br />

Staffs are present to answer incoming calls during agency’s<br />

normal operating hours.<br />

3.0 Clients Rights and Responsibilities<br />

3.1 Clients Rights<br />

Agency will provide client with written copy of client rights<br />

and responsibilities, including:<br />

• Informed consent<br />

• Confidentiality<br />

• Grievance procedures<br />

• Duty to warn or report certain behaviors<br />

• Scope of service<br />

• Criteria for end of services<br />

3.2 Confidentiality<br />

Agency has Policy and Procedure regarding client<br />

confidentiality in accordance with RWGA /TRG site visit<br />

guidelines, local, state and federal laws. Providers must<br />

implement mechanisms to ensure protection of clients’<br />

confidentiality in all processes throughout the agency.<br />

There is a written policy statement regarding client<br />

confidentiality form signed by each employee and included in<br />

the personnel file.<br />

3.3<br />

Consents<br />

All consent forms comply with state and federal laws, are<br />

signed by an individual legally able to give consent and must<br />

include the Consent for <strong>Service</strong>s form and a consent for<br />

release/exchange of information for every individual/agency to<br />

whom client identifying information is disclosed, regardless of<br />

whether or not HIV status is revealed.<br />

• Staff time sheets or other documentation indicate compliance<br />

• Published documentation of agency operating hours<br />

• Staff time sheets or other documentation indicate compliance<br />

• Documentation in client’s record<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Clients interview indicates compliance<br />

• Agency’s structural layout and information management<br />

indicates compliance<br />

• Signed confidentiality statement in each employee’s personnel<br />

file<br />

• Agency Policy and Procedure and signed and dated consent<br />

forms in client record<br />

Page 13 of 72

3.4<br />

3.5<br />

Up to date Release of Information<br />

Agency obtains an informed written consent of the client or<br />

legally responsible person prior to the disclosure or exchange<br />

of certain information about client’s case to another party<br />

(including family members) in accordance with the RWGA<br />

<strong>Site</strong> Visit Guidelines, local, state and federal laws. The<br />

release/exchange consent form must contain:<br />

• Name of the person or entity permitted to make the<br />

disclosure<br />

• Name of the client<br />

• The purpose of the disclosure<br />

• The types of information to be disclosed<br />

• Entities to disclose to<br />

• Date on which the consent is signed<br />

• The expiration date of client authorization (no longer<br />

than two years or six (6) months to one (1) year from<br />

last date of service)<br />

• Signature of the client/or parent, guardian or person<br />

authorized to sign in lieu of the client.<br />

• Description of the Release of Information, its<br />

components, and ways the client can nullify it<br />

Released/exchange of information forms must be completed<br />

entirely in the presence of the client. Any unused lines must<br />

have a line crossed through the space.<br />

Grievance Procedure<br />

Agency has Policy and Procedure regarding client grievances<br />

that is reviewed with each client in a language and format the<br />

client can understand and a written copy of which is provided<br />

to each client.<br />

Grievance procedure includes but is not limited to:<br />

• to whom complaints can be made<br />

• steps necessary to complain<br />

• form of grievance, if any<br />

• time lines and steps taken by the agency to resolve the<br />

grievance<br />

• Current Release of Information form with all the required<br />

elements signed by client or authorized person in client’s record<br />

• Signed receipt of agency Grievance Procedure, filed in client<br />

chart<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

Page 14 of 72

3.6<br />

• documentation by the agency of the process<br />

• confidentiality of grievance<br />

• addresses and phone numbers of licensing authorities<br />

and funding sources<br />

Client Rights and Responsibilities Statement<br />

Agency has a Client Rights and Responsibilities Statement that<br />

is reviewed with each client in a language and format the client<br />

can understand and a written copy of which is provided to each<br />

client.<br />

3.7 Client Feedback<br />

Feedback from clients (or from client caregivers, in cases<br />

where clients are unable to give feedback) is obtained about<br />

quality of services annually.<br />

3.8 Patient Safety (Core <strong>Service</strong>s Only)<br />

Agency shall establish mechanisms to implement the<br />

National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) modeled after the<br />

current Joint Commission accrediatation for Ambulatory<br />

Care (www.jointcommission.org) to ensure patients’ safety.<br />

The NPSG to be addressed include the following:<br />

• “Improve the accuracy of patient identification<br />

• Improve the safety of using medications<br />

• Reduce the risk of Health care-associated infections<br />

• Accurately and completely reconcile medications<br />

across the continuum of care<br />

• Universal Protocol” for preventing Wrong <strong>Site</strong>, Wrong<br />

Procedure and Wrong Person Surgery”<br />

(www.jointcommission.org)<br />

4.0 Accessibility<br />

4.1 Cultural Competence<br />

Agency demonstrates a commitment to provision of services<br />

• Agency Policy and Procedure and signed receipt of Clients<br />

Rights and Responsibilities Statement in client record<br />

• Client feedback mechanism is in place<br />

• Documentation of clients’ evaluation of services is<br />

maintained<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Agency has procedures for obtaining translation services<br />

• Client satisfaction survey indicates compliance<br />

Page 15 of 72

that are culturally sensitive and language competent for Limited<br />

English Proficient (LEP) individuals.<br />

4.2 Client Education<br />

Agency demonstrates capacity for client education and<br />

provision of Information on community resources<br />

4.3 Special <strong>Service</strong> Needs<br />

Agency demonstrates a commitment to assisting individuals<br />

with special needs<br />

4.4 Program Information<br />

Broad-based dissemination of information regarding the<br />

availability of services<br />

4.5<br />

4.6<br />

Proof of HIV Diagnosis<br />

Documentation of the client's HIV status is obtained at or prior<br />

to the initiation of services or registration services.<br />

An anonymous test result may be used to document HIV status<br />

temporarily (up to sixty [60] days). It must contain enough<br />

information to ensure the identity of the subject with a<br />

reasonable amount of certainty.<br />

Client Eligibility<br />

In order to be eligible for services, individuals must meet the<br />

following:<br />

• HIV+<br />

• Residence in the Houston EMA/ HSDA (With prior<br />

approval, clients can be served if they reside outside<br />

of the Houston EMA/HSDA.)<br />

• Income no greater than 300% of the Federal Poverty<br />

level (unless otherwise indicated)<br />

• Policies and procedures demonstrate commitment to the<br />

community and culture of the clients<br />

• Availability of interpretive services, bilingual staff, and staff<br />

trained in cultural competence<br />

• Agency has vital documents including, but not limited to<br />

applications, consents, complaint forms, and notices of rights<br />

translated in client record<br />

• Availability of the blue book and other educational materials<br />

• Documentation of educational needs assessment and client<br />

education in clients’ records<br />

• Agency compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act<br />

(ADA).<br />

• Review of Policies and Procedures indicates compliance<br />

• Environmental Review<br />

• Format Agency has a written substantiated annual plan to<br />

targeted populations<br />

• Zip code data show provider is reaching clients throughout<br />

service area<br />

• Documentation in client record as per RWGA site visit<br />

guidelines or TRG Policy SG-03<br />

• Documentation of HIV+ status, residence, identification and<br />

income in the client record<br />

• Documentation of ineligibility for third party reimbursement<br />

• Documentation of screening for Third Party Payers in<br />

accordance with TRG Policy SG-06 Documentation of Third<br />

Party Payer Eligibility or RWGA site visit guidelines<br />

Page 16 of 72

• Proof of identification<br />

• Ineligibility for third party reimbursement<br />

4.7 Re-evaluation of Client Eligibility<br />

Agency conducts annual re-evaluation of eligibility for all<br />

clients. At a minimum, agency confirms renewed eligibility<br />

with the CPCDMS and re-screens, as appropriate, for third-<br />

party payers.<br />

4.8 Linkage Into Core <strong>Service</strong>s<br />

Agency staff will provide out-of-care clients with<br />

individualized information and referral to connect them into<br />

ambulatory outpatient medical care and other core medical<br />

services.<br />

4.9 Wait Lists<br />

It is the expectation that clients will not be put on a Wait List<br />

nor will services be postponed or denied due to funding.<br />

Agency must notify the Administrative agency when funds<br />

for service are either low or exhausted for appropriate<br />

measures to be taken to ensure adequate funding is available.<br />

Should a wait list become required, the agency must, at a<br />

minimum, develop a policy that addresses how they will<br />

handle situations where service(s) cannot be immediately<br />

provided and a process by which client information will be<br />

obtained and maintained to ensure that all clients that<br />

requested service(s) are contacted after service provision<br />

resumes;<br />

The A gency w ill n otify The R esource G roup ( TRG) or<br />

RWGA of the following information when a wait list must be<br />

created:<br />

An explanation for the cessation of service; and<br />

A plan for resumption of service. The Sub grantee’s plan<br />

must address:<br />

• Action steps to be taken by Subgrantee to resolve the<br />

service shortfall; and<br />

• Projected date that services will resume.<br />

• Client file contains documentation of re-evaluation of client<br />

residence, income and rescreening for third party payers at<br />

least annually<br />

• Documentation of client referral is present in client file<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Documentation of compliance with TRG’s Policy SG-19 Client<br />

Wait Lists<br />

• Documentation that agency notified their Administrative<br />

Agency when funds for services were either low or exhausted<br />

Page 17 of 72

The A gency w ill r eport to T RG or R WGA in w riting on a<br />

monthly b asis) w hile a c lient w ait l ist i s r equired w ith t he<br />

following information:<br />

• Number of clients on the wait list<br />

• Progress toward completing the plan for resumption of<br />

service<br />

• A revised plan for resumption of service, if necessary<br />

4.10 Intake<br />

The agency conducts an intake to collect required data<br />

including, but not limited, eligibility, appropriate consents and<br />

client identifiers for entry into CPCDMS. Intake process is<br />

flexible and responsive, accommodating disabilities and health<br />

conditions.<br />

When necessary, client is provided alternatives to office visits,<br />

such as conducting business by mail or providing home visits.<br />

Agency has established procedures for communicating with<br />

people with hearing impairments<br />

5.0 Quality Management<br />

5.1 Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI)<br />

Agency demonstrates capacity for an organized CQI program<br />

and has a CQI Committee in place to review procedures and to<br />

initiate Performance Improvement activities.<br />

The Agency shall maintain an up-to-date Quality Management<br />

(QM) Manual. The QM Manual will contain at a minimum:<br />

• The Agency’s QM Plan<br />

• Meeting agendas and/or notes (if applicable)<br />

• Project specific CQI Plans<br />

• Root Cause Analysis & Improvement Plans<br />

• Data collection methods and analysis<br />

• Work products<br />

• Documentation in client record<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Up to date QM Manual<br />

Page 18 of 72

• QM program evaluation<br />

• Materials necessary for QM activities<br />

5.2 Data Collection and Analysis<br />

Agency demonstrates capacity to collect and analyze client<br />

level data including client satisfaction surveys and findings are<br />

incorporated into service delivery. Supervisors shall conduct<br />

and document ongoing record reviews as part of quality<br />

improvement activity.<br />

6.0 Point Of Entry Agreements<br />

6.1 Points of Entry (Core <strong>Service</strong>s Only)<br />

Agency accepts referrals from sources considered to be<br />

points of entry into the continuum of care, in accordance with<br />

HIV <strong>Service</strong>s policy approved by <strong>HRSA</strong> for the Houston<br />

EMA.<br />

7.0 Emergency Management<br />

7.1 Emergency Preparedness<br />

Agency leadership including medical staff must develop an<br />

Emergency Preparedness Plan modeled after the Joint<br />

Commission’s regulations and/or Centers for Medicare and<br />

Medicaid guidelines for Emergency Management. The plan<br />

should, at a minimum utilize “all hazard approach” to ensure<br />

a level of preparedness sufficient to support a range of<br />

emergencies. Agencies shall conduct an annual Hazard<br />

Vulnerability Analysis (HVA) to identify potential hazards,<br />

threats, and adverse events and assess their impact on care,<br />

treatment, and services they must sustain during an<br />

emergency. The agency shall communicate hazards<br />

identified with its community emergency response agencies<br />

and together shall identify the capability of its community in<br />

meeting their needs. The HVA shall be reviewed annually.<br />

7.2<br />

Emergency Preparedness Plan<br />

The emergency preparedness plan shall address the six<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Up to date QM Manual<br />

• Supervisors log on record reviews signed and dated<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Documentation of formal agreements with appropriate Points<br />

of Entry<br />

• Documentation of referrals and their follow-up<br />

• Emergency Preparedness Plan<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Emergency Preparedness Plan<br />

Page 19 of 72

critical areas for emergency management including<br />

• Communication pathways<br />

• Essential resources and assets<br />

• patients’ safety and security<br />

• staff responsibilities<br />

• Supply of key utilities such as portable water and<br />

electricity<br />

• Patient clinical and support activities during<br />

emergency situations. (www.jointcommission.org)<br />

7.3 Emergency Management Drills<br />

Agency shall implement emergency management drills twice<br />

a year either in response to actual emergency or in a planned<br />

exercise. Completed exercise should be evaluated by a<br />

multidisciplinary team including administration, clinical and<br />

support staff. The emergency plan should be modified based<br />

on the evaluation results and retested.<br />

8.0 Building Safety<br />

8.1 Required Permits<br />

All agencies will maintain Occupancy and Fire Marshal’s<br />

permits for the facilities.<br />

• Emergency Management Plan<br />

• Review of Agency’s Policies and Procedures Manual indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Current required permits on file<br />

Page 20 of 72

Oral Health Care<br />

Oral Health care constitute an essential component of primary health care for PLWHA as poor oral health affects adherence to ARV therapy and<br />

subsequent health outcomes 4<br />

. Thus, there is the need for coordination of services between medical providers and oral health care providers.<br />

The Oral health care standards are based on <strong>HRSA</strong> definition for oral health care, the <strong>New</strong> York State Health Department AIDS Institute<br />

guidelines for HIV and Oral Health and other state and local requirements. The RW HIV/AIDS Treatment Modernization Act of 2006 defines<br />

Oral Health Care as “diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic services provided by the general dental practitioners, dental specialist, dental<br />

hygienist and auxiliaries and other trained primary care providers”. The Ryan White Part A/B oral health care services include standard<br />

preventive procedures, diagnosis and treatment of HIV-related oral pathology, restorative dental services, oral surgery, root canal therapy, fixed<br />

and removable prosthodontics and oral medication (including pain control) for HIV patients 15 years old or older based on a comprehensive<br />

individual treatment plan.<br />

1.0 Staff Requirements<br />

1.1 Continuing Education<br />

Eight (8) hours of training in HIV/AIDS and clinically-related<br />

issues is required annually for licensed staff.<br />

One (1) hour of training in HIV/AIDS is required annually for all<br />

staff.<br />

1.2 Experience – HIV/AIDS<br />

A minimum of one (1) year documented HIV/AIDS work<br />

experience is preferred for licensed staff.<br />

1.3 Staff Supervision<br />

Supervision of clinical staff shall be provided by a practitioner with<br />

at least two years experience in dental health assessment and<br />

treatment of persons with HIV. All licensed personnel shall<br />

received supervision consistent with the State of Texas license<br />

requirements.<br />

• Materials for staff training and continuing<br />

education are on file<br />

• Documentation of continuing education in<br />

personnel file<br />

• Documentation of work experience in<br />

personnel file<br />

• Review of personnel files indicates<br />

compliance<br />

• Review of agency’s Policies & Procedures<br />

Manual indicates compliance<br />

4<br />

The <strong>New</strong> York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (2000-2009). Clinical guidelines: HIV and oral health. Retrieved 10/02/2009 from www.<br />

http://www.hivguidelines.org/Content.aspx?PageID=263<br />

Page 21 of 72

2.0 Coordination with Primary Care Providers<br />

2.1 HIV Primary Care Provider Contact Information<br />

Agency obtains and documents HIV primary care provider contact<br />

information for each client.<br />

2.2 Consultation for Treatment<br />

Agency consults with client’s medical care providers when<br />

indicated.<br />

2.3 Health History Information<br />

Agency collects and documents health history information for each<br />

client prior to providing care. This information should include, but<br />

not be limited to, the following:<br />

• A baseline current (within the last 6 months) CBC laboratory<br />

test results for all new clients, and an annual update<br />

thereafter<br />

• Current (within the last 6 months) Viral Load and CD4<br />

laboratory test results, when clinically indicated<br />

• Client’s chief complaint, where applicable<br />

• Medication names<br />

• Sexually transmitted diseases<br />

• HIV-associated illnesses<br />

• Allergies and drug sensitivities<br />

• Alcohol use<br />

• Recreational drug use<br />

• Tobacco use<br />

• Neurological diseases<br />

• Hepatitis<br />

• Usual oral hygiene<br />

• Date of last dental examination<br />

• Involuntary weight loss or weight gain<br />

Review of systems<br />

• Documentation of HIV primary care<br />

provider contact information in the client<br />

record. At minimum, agency should collect<br />

the clinic and/or physician’s name and<br />

telephone number<br />

• Documentation of communication in the<br />

client record<br />

• Documentation of health history<br />

information in the client record. Reasons<br />

for missing health history information are<br />

documented<br />

Page 22 of 72

2.4 Client Health History Update<br />

An update to the health history should be made, at minimum, every<br />

six (6) months or at client’s next general dentistry visit whichever<br />

is greater.<br />

2.5<br />

Comprehensive Periodontal Examination<br />

Agency has a written policy and procedure regarding when a<br />

comprehensive periodontal examination should occur.<br />

Comprehensive periodontal examination should be done in<br />

accordance with professional standards and current US Public<br />

Health <strong>Service</strong> guidelines<br />

2.6 Treatment Plan<br />

• A comprehensive, multi disciplinary Oral Health treatment<br />

plan will be developed in conjunction with the patient.<br />

• Patient’s primary reason for dental visit should be addressed<br />

in treatment plan<br />

• Patient strengths and limitations will be considered in<br />

development of treatment plan<br />

• Treatment priority should be given to pain management,<br />

infection, traumatic injury or other emergency conditions<br />

• Treatment plan will be updated as deemed necessary<br />

2.7 Annual Hard/Soft Tissue Examination<br />

The following elements are part of each client’s annual hard/soft<br />

tissue examination and are documented in the client record:<br />

• Charting of caries;<br />

• X-rays;<br />

• Periodontal screening;<br />

• Written diagnoses, where applicable;<br />

• Treatment plan.<br />

Determination of clients needing annual examination should be<br />

based on the dentist’s judgment and criteria outlined in the<br />

• Documentation of health history update in<br />

the client record<br />

• Review of agency’s Policies & Procedures<br />

Manual indicates compliance<br />

• Review of client records indicate<br />

compliance<br />

• Treatment plan dated and signed by both<br />

the provider and patient in patient file<br />

• Updated treatment plan dated and signed by<br />

both the provider and patient in patient file<br />

• Documentation in the client record<br />

• Review of agency’s Policies & Procedures<br />

Manual indicates compliance<br />

Page 23 of 72

agency’s policy and procedure, however the time interval for<br />

all clients may not exceed two (2) years.<br />

2.8 Oral Hygiene Instructions<br />

Oral hygiene instructions (OHI) should be provided annually to<br />

each client. The content of the instructions is documented.<br />

THRESHOLDS<br />

Measurement thresholds will be set at 100%.<br />

IV. IMPLEMENTATION & REPORTING<br />

• Documentation in the client record<br />

Agencies will be required to adhere to the QA guidelines provided by RWGA, or the Part B administrative agency, as applicable.<br />

Page 24 of 72

Findings from the 2008 Houston Area HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment<br />

CORE CORE CORE SERVICES<br />

SERVICES<br />

SERVICES<br />

reported frequently as a barrier. Waiting times were also ranked highly within<br />

subpopulations, except within the out-of-care and youth. Information-related barriers were<br />

ranked highly within the out-of-care, women, African-Americans, the recently released and<br />

substance abusers.<br />

V<br />

DENTIST ENTIST VVISITS<br />

ISITS<br />

<strong>Service</strong> category data were collected in the context of their local definitions, rather<br />

than their official <strong>HRSA</strong> definitions. Although the differences between the local and <strong>HRSA</strong><br />

definitions are minimal, the Data Collection Workgroup felt the local definition approach<br />

would promote a realistic assessment of the Houston HSDA Ryan White care system.<br />

Local definitions for each service category will be included in each summary. A list<br />

of the official <strong>HRSA</strong> service category definitions is provided in Appendix C.<br />

Local Definition<br />

The local definition of dentist visits is defined as:<br />

Restorative dental services, oral surgery, root canal therapy, fixed and removable<br />

prosthodontics; periodontal services includes subgingival scaling, gingival curettage,<br />

osseous surgery, gingivectomy, provisional splinting, laser procedures and maintenance.<br />

Oral medication (including pain control) for HIV patients 15 years old or older must be<br />

based on a comprehensive individual treatment plan.<br />

CPCDMS/ARIES <strong>Service</strong> Utilization Data<br />

Page 25 of 72<br />

<strong>Service</strong> utilization information for most services is based on data from the<br />

Centralized Patient Care Data Management System (CPCDMS) and/or ARIES. The<br />

CPCDMS is a real-time, de-identified client-level computer database application that allows<br />

Ryan White-funded providers, as well as non-Ryan White providers, and other users in the<br />

EMA to share client eligibility information and document service delivery while maintaining<br />

client confidentiality. <strong>Service</strong> providers enter registration, service encounter and medical<br />

update information for each client into the CPCDMS. Client information collected includes<br />

demographic, comorbidity, biological marker, mortality and service utilization data. Since its<br />

inception in June of 2000, over 10,000 clients have been registered in the CPCDMS.<br />

The AIDS Regional Information and Evaluation System (ARIES), implemented in<br />

February 2005, is also a real-time, de-identified client-level computer database application,<br />

the ARIES centralizes client data, service details, and agency and staff information to<br />

maximize the quality of care and services to clients in need. The system was developed<br />

collaboratively for Part B by the State of Texas, County of San Diego, County of San<br />

Bernardino, and State of California. Information from the Centralized Patient Care Data<br />

Management System can be imported into the ARIES system and filtered to produce a<br />

comprehensive picture of service utilization information on both Part B and Part A-funded<br />

providers, as well as other users in the EMA/HSDA<br />

2008 Houston Area HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment

It is important to note that while CPCDMS does represent the majority of PLWHA<br />

receiving Ryan White-funded services in the HSDA, it is incorrect to assume that all 764<br />

survey respondents are enrolled in CPCDMS.<br />

According to the Centralized Patient Care Data Management System (CPCDMS), a<br />

total of 2,219 unduplicated PLWHA received dentist visits through grants billed to Ryan<br />

White Part A and Part B. This total represents 12% of the reported 18,109 PLWHA residing<br />

in the Houston EMA/HSDA.<br />

Access (Easy versus Hard)<br />

At the beginning of the client survey, respondents were given a list of core services<br />

arranged in table format (see Appendix B for copy of client survey). The purpose of the<br />

core service table was to collect information on access and barriers to the listed services.<br />

For each <strong>HRSA</strong>-defined core service, respondents indicated whether they had “some<br />

difficulty” getting the service, if it was “very easy” to get the service, or if they “did not need”<br />

the service within the past year.<br />

The following table shows the level of access to dentist visits reported by all<br />

respondents. It should be noted that the percentages are based on the sum of<br />

respondents within each subpopulation that accessed the service (reported difficulty or<br />

ease). It is also important to remember that the subpopulations are not mutually exclusive<br />

– in other words, the numbers across the subpopulations do not represent unduplicated<br />

respondents. For example, an African-American female reporting a mental health symptom<br />

is included in the Women, African-Americans and Mental Health subpopulations.<br />

Care should also be taken when making comparisons between subpopulations of<br />

very small size. The smaller the subpopulation, the more sensitive percentages become to<br />

changes in the numbers. For example, for very small subpopulations, shifting just one<br />

response can change percentages by as much as 5 points. It is important not to rely solely<br />

on such percentages when planning for services – considering both the proportions and<br />

raw numbers will help ensure a more comprehensive understanding of the results.<br />

Lastly, it should be emphasized that reports of access to a service does not<br />

necessarily mean the respondent received the service. In the client survey, respondents<br />

were asked to report whether they had difficulty getting a service, but the survey did not ask<br />

as a follow-up whether the respondent ultimately received the service despite the<br />

difficulties. So, care should be taken not to equate reports of “very easy” or reports of<br />

“some difficulty” as proxies of service utilization.<br />

2008 Houston Area HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment<br />

DENTIST DENTIST DENTIST VISITS VISITS VISITS<br />

Page 26 of 72

CORE CORE CORE SERVICES<br />

SERVICES<br />

SERVICES<br />

TABLE 15.1: REPORTED ACCESS TO DENTIST VISITS IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS<br />

Total who<br />

attempted<br />

to access<br />

* Subpopulations are not mutually exclusive.<br />

** Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.<br />

%<br />

Very<br />

Easy<br />

The majority (82%) of all 764 survey respondents reported attempting to access<br />

dentist visits during the previous 12 months; a total of 138 (18%) said they did not need this<br />

service. Most subpopulations also reported accessing this service in relatively high<br />

proportions – Latinos access this service in the highest proportion (90%) compared to other<br />

groups. However, the subpopulations with the lowest proportions accessing dentist visits<br />

were substance abusers (79%), the recently released (77%) and the out-of-care (58%).<br />

Overall, the majority of all survey respondents had an easy time accessing dentist<br />

visits – 61% said it was “very easy” to get the service. Among the subpopulations, access<br />

to dentist visits appeared easiest for Latinos (70%), MSM of color (69%) and those in-care<br />

(64%).<br />

By far, the out-of-care subpopulation had the highest proportion (78%) of those who<br />

had some difficulty accessing dentist visits during the past year. Other subpopulations with<br />

relatively higher proportions of difficulty were youth (65%), women (45%) and the recently<br />

released (43%).<br />

Barriers<br />

Survey respondents that reported “some difficulty” getting a service were asked to<br />

describe the barriers they experienced. Respondents could choose from a list of common<br />

barriers, or write their own. The number of possible reported barriers was unlimited, so<br />

respondents were encouraged to list every barrier they encountered when getting a<br />

service. It should also be noted that the number of reported barriers does not indicate<br />

%<br />

Some<br />

Difficulty<br />

%<br />

No<br />

Need<br />

All Respondents (N=764) 626 82% 380 61% 246 39% 138 18%<br />

Subpopulations*<br />

In Care 581 85% 370 64% 211 36% 106 15%<br />

Out-of-Care 45 58% 10 22% 35 78% 32 42%<br />

Women 197 83% 108 55% 89 45% 41 17%<br />

Youth 31 84% 11 35% 20 65% 6 16%<br />

African-Americans 349 81% 214 61% 135 39% 80 19%<br />

Latinos 127 90% 89 70% 38 30% 14 10%<br />

White MSM 83 81% 47 57% 36 43% 20 19%<br />

MSM of Color 179 86% 124 69% 55 31% 29 14%<br />

Recently Released 92 77% 51 55% 41 45% 27 23%<br />

Substance Abuse 196 79% 113 58% 83 42% 52 21%<br />

Mental Health 369 82% 209 57% 160 43% 83 18%<br />

Homeless 64 72% 42 47% 22 25% 25 28%<br />

Page 27 of 72<br />

2008 Houston Area HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment<br />

%

whether the respondent did, or did not, ultimately receive the service – survey respondents<br />

described the barriers they experienced in the process of getting a service.<br />

The following table shows the number of barriers reported for dentist visits. The<br />

numbers in each cell represent how many times respondents faced a certain type of<br />

barrier. The total reported barriers column on the far right represents the total number of<br />

barriers reported for each subpopulation. The cells that are shaded and in bold represent<br />

barriers with the highest number of reports for each subpopulation.<br />

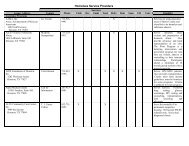

TABLE 15.2: NUMBER OF REPORTED BARRIERS FOR DENTIST VISITS<br />

A B C D E F G H I J K M O Q R S<br />

Total**<br />

Barriers<br />

All Respondents<br />

Subpopulations*<br />

33 58 74 26 15 17 27 87 43 6 10 5 24 1 4 1 431<br />

In Care 26 44 63 16 11 8 25 75 33 4 4 3 18 1 3 1 335<br />

Out-of-Care 7 14 11 10 4 9 2 12 10 2 6 2 6 0 1 0 96<br />

Women 12 21 27 15 7 10 9 29 21 6 6 0 12 1 1 0 177<br />

Youth 6 10 5 3 5 1 3 6 4 2 2 0 3 0 1 0 51<br />

African-Americans 19 36 34 19 8 13 11 49 18 5 8 4 14 0 3 1 242<br />

Latinos 7 8 12 4 3 2 5 15 6 0 1 0 5 0 0 0 68<br />

White MSM 5 5 17 1 2 0 8 14 7 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 61<br />

MSM of Color 7 15 14 3 4 3 5 22 4 0 0 3 7 0 1 0 88<br />

Recently Released 5 10 14 11 2 4 3 13 6 0 3 4 2 0 1 0 78<br />

Substance Abuse 11 19 24 9 1 4 4 33 15 2 5 2 7 0 1 0 137<br />

Mental Health 21 38 55 20 10 13 17 55 32 5 8 2 15 1 4 1 297<br />

Homeless 8 15 13 12 8 7 6 14 3 3 7 0 0 0 1 1 102<br />

* Subpopulations are not mutually exclusive.<br />

** Some barriers may not be shown if no respondents reported them as barriers for this service<br />

Barriers<br />

A The services are not in my area L People at the agency don't speak my language<br />

B I don't know where to get the services M My jail/prison history makes it hard to get services<br />

C I would have to wait too long to get the services N Difficulties with paperwork (volume, confusing process, etc)<br />

D The services cost too much O Substance abuse<br />

E I was told I am not eligible to get the services P Was incarcerated/in jail<br />

F I don't think I'm eligible to get the services Q Personal health issues (too sick, medication resistant, etc)<br />

G The people who run the services are not friendly R Fear, denial or stigma (internal and/or external)<br />

H It's hard to make or keep appointments S Homeless/unstable housing<br />

I It's hard for me to get there T CM left/staff turnover<br />

J There is no one to watch my kids if I go there U Not enough, resources/funds run out too quickly<br />

K I'm afraid someone will find out about my HIV V Immigration status<br />

Overall, there were 431 reports of barriers among respondents who had difficulty<br />

accessing dentist visits during the past year. The barriers reported most often for dentist<br />

visits were related to scheduling appointments, getting to locations of services and waiting<br />

2008 Houston Area HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment<br />

DENTIST DENTIST DENTIST VISITS VISITS VISITS<br />

Page 28 of 72

CORE CORE CORE SERVICES<br />

SERVICES<br />

SERVICES<br />

times. The table below shows 2-3 highlighted barriers reported by subpopulations when<br />

accessing dentist visits. The intent of this table is to highlight the barriers identified most<br />

often by respondents – for the full list of barriers, refer to the table titled, “Number of<br />

reported barriers for Dentist Visits.”<br />

TABLE 15.3: HIGHLIGHTED BARRIERS FOR DENTIST VISITS BY SUBPOPULATION<br />

All Respondents<br />

Subpopulations*<br />

In Care<br />

Out-of-Care<br />

Women<br />

Youth<br />

African-Americans<br />

Latinos<br />

White MSM<br />

MSM of Color<br />

Recently Released<br />

Substance Abuse<br />

Mental Health<br />

Homeless<br />

* Subpopulations are not mutually exclusive.<br />

Barriers (ranked by number of reports)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=87)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=74)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=75)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=63)<br />

B – I don't know where to get the services (n=14)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=12)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=29)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=27)<br />

B – I don't know where to get the services (n=10)<br />

A – The services are not in my area (n=6)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=6)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=49)<br />

B – I don't know where to get the services (n=36)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=34)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=15)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=12)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=17)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=14)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=22)<br />

B – I don't know where to get the services (n=15)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=14)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=14)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=13)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=33)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=24)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=55)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=55)<br />

B – I don't know where to get the services (n=15)<br />

H – It's hard to make or keep appointments (n=14)<br />

C – I would have to wait too long to get the services (n=13)<br />

D – The services cost too much (n=12)<br />

Page 29 of 72<br />

Within all subpopulations, problems making or keeping appointments ranked high<br />

compared to other barriers. Waiting times were also ranked highly within subpopulations,<br />

except within the out-of-care and youth. Information-related barriers were ranked highly<br />

within African-Americans, women, MSM of color, out-of-care and youth.<br />

2008 Houston Area HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment

Ryan White Part A Quality Management Program–Houston EMA<br />

CONTACT:<br />

Oral Health Care Chart Review<br />

FY 2009<br />

Prepared by <strong>Harris</strong> County Public Health &<br />

Environmental <strong>Service</strong>s – Ryan White Grant Administration<br />

August 2009<br />

Carin Martin, MPA<br />

Project Coordinator–Quality Management Development<br />

<strong>Harris</strong> County Public Health & Environmental <strong>Service</strong>s<br />

Ryan White Grant Administration<br />

2223 West Loop South, RM 417<br />

Houston, TX 77027<br />

713-439-6041<br />

cmartin@hcphes.org<br />

Page 30 of 72

Introduction<br />

Part A funds of the Ryan White Care Act are administered in the Houston Eligible Metropolitan Area (EMA) by the<br />

Ryan White Grant Administration Section of <strong>Harris</strong> County Public Health & Environmental <strong>Service</strong>s. During FY<br />

09, a comprehensive review of client dental records was conducted for services provided between 3/1/07 to<br />

2/28/08. This review included one provider of Adult Oral Health Care that received Part A funding in the<br />

Houston EMA.<br />

The primary purpose of this annual review process is to assess Part A oral health care provided to persons living<br />

with HIV in the Houston EMA. Ryan White Grant Administration manages the review process and analyzes the<br />

subsequent data, while the reviews are conducted by TMF Health Quality Institute (TMF), under contract with<br />

Ryan White Grant Administration. Unlike primary care, there are no federal guidelines published by the U.S Public<br />

Health <strong>Service</strong> for oral health care targeting individuals with HIV/AIDS. Therefore, Ryan White Grant<br />

Administration has adopted general guidelines from peer-reviewed literature that address oral health care for the<br />

HIV/AIDS population, as well as literature published by national dental organizations such as the American Dental<br />

Association and the Academy of General Dentistry, to measure the quality of Part A funded oral health care.<br />

Scope of This Report<br />

This report provides background on the project, supplemental information on the design of the data collection tool,<br />

and presents the pertinent findings of the FY 09 oral health care chart review. In addition to this report, the<br />

reviewed provider will also receive an electronic copy of the raw database in order to facilitate further analysis.<br />

Also, any additional data analysis of items or information not included in this report can likely be provided after a<br />

request is submitted to Ryan White Grant Administration.<br />

The Data Collection Tool<br />

The data collection tool employed in the review was developed through a period of in-depth research and a series of<br />

working meetings between Ryan White Grant Administration and the review contractor, TMF. By studying the<br />

processes of previous dental record reviews and researching the most recent HIV-related and general oral health<br />

practice guidelines, a listing of potential data collection items was developed. Further research provided for the<br />

editing of this list to yield what is believed to represent the most pertinent data elements for oral health care in the<br />

Houston EMA. Topics covered by the data collection tool include, but are not limited to the following: basic client<br />

information, completeness of the health history, hard & soft tissue examinations, oral hygiene prevention, and<br />

periodontal examinations. Contact Ryan White Grant Administration for a copy of the tool.<br />

The Chart Review Process<br />

Page 31 of 72<br />

All charts were reviewed by licensed dentist experienced in identifying documentation issues and assessing<br />

adherence to published guidelines. The reviewer has extensive experience conducting dental chart reviews. The<br />

collected data was recorded directly onto the tool and this information was entered into a preformatted database.<br />

Once all data collection and data entry was completed, the database was forwarded to Ryan White Grant<br />

Administration for analysis. The data collected during this process is intended to be used for service improvement.

The Chart Review Process (cont’d)<br />

The specific parameters established for the data collection process were developed from HIV-related and general<br />

oral health care guidelines available in peer-reviewed literature, and the professional experience of the reviewer on<br />

standard record documentation practices. Table 1 summarizes the various documentation criteria employed during<br />

the review.<br />

Table 1. Data Collection Parameters<br />

Review Area Documentation Criteria<br />

Health History Completeness of Initial Health History: includes but not limited to past medical<br />

history, medications, allergies, substance use, HIV MD/primary care status, physician<br />

contact info, etc.; Completed updates to the initial health history<br />

Hard/Soft Tissue Exam Findings—abnormal or normal, diagnoses, treatment plan, treatment plan updates<br />

Oral Hygiene Prevention Prophylaxis, OHI<br />

Periodontal screening Completeness<br />

Appointments Kept, Not kept, Practitioner<br />

The Sample Selection Process<br />

The sample population was selected from a pool of 2,269 unduplicated clients who accessed Part A oral health care<br />

between 3/1/08 and 2/28/09. The medical charts of 205 of these clients were used in the review, representing 9%<br />

of the pool of unduplicated clients.<br />

In an effort to make the sample population as representative of the actual Part A oral health care population as<br />

possible, the EMA’s Centralized Patient Care Data Management System (CPCDMS) was used to generate a list of<br />

client codes to be reviewed. The demographic make-up (race/ethnicity, gender, age, stage of illness) of clients<br />

accessing oral health services between 3/1/08 and 2/28/09 was determined by CPCDMS, which in turn allowed<br />

Ryan White Grant Administration to generate a sample of specified size that closely mirrors that same demographic<br />

make-up. Randomly-generated client codes were categorized in terms of stage of illness, as delineated by CPCDMS,<br />

in order to allow for assessment of a range of care.<br />

- Asymptomatic CD4 > = 500 - Symptomatic CD4 200-499<br />

- Asymptomatic CD4 200-499 - Symptomatic CD4 < 200<br />

- Asymptomatic CD4 < 200 - AIDS CD4 > = 500<br />

- Symptomatic CD4 > = 500 - AIDS CD4 200-499<br />

- AIDS CD4 < 200<br />

Page 32 of 72<br />

The lists of client codes were usually forwarded to the reviewer and corresponding agencies 5-10 business days<br />

before reviews were scheduled to commence.

Characteristics of the Sample Population<br />

The review sample population was generally comparable to the Part A population receiving oral health care in terms<br />

of race/ethnicity, gender, age and stage of illness. 1<br />

It is important to note that the chart review findings in this<br />

report apply only to those who receive oral health care from a Part A provider and cannot be generalized to all Ryan<br />

White clients or to the broader population of persons with HIV or AIDS. Table 2 compares the review sample<br />

population with the Ryan White Part A oral health care population as a whole.<br />

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics of FY 08 Houston EMA Ryan White Part A Oral Health Care Clients<br />

Sample Ryan White Part A EMA<br />

Race/Ethnicity Number Percent Number Percent<br />

African American 91 44% 1037 46%<br />

White 109 53% 1186 52%<br />

Asian 1 1% 20 1%<br />

Native Hawaiian/Pacific<br />

Islander 1 1% 4

Findings<br />

Appointments<br />

To reduce the number of no-show appointments, the appointment policy at the agency requires patients to call at<br />

least twenty-four hours in advance if their appointment must be canceled or rescheduled. If a patient fails to follow<br />

this policy more than twice, they are no longer eligible for regularly scheduled appointments, but instead are<br />

scheduled for block appointments where groups of patients are scheduled at the same time. While this strategy may<br />