Shopping Externalities and Self Fulfilling Unemployment Fluctuations*

Shopping Externalities and Self Fulfilling Unemployment Fluctuations*

Shopping Externalities and Self Fulfilling Unemployment Fluctuations*

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

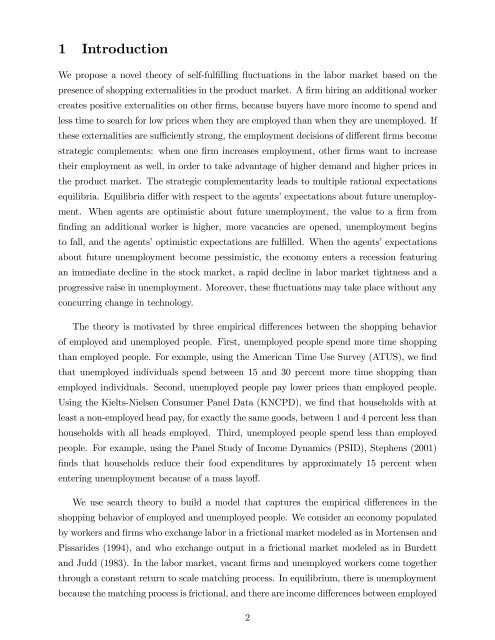

1 IntroductionWe propose a novel theory of self-ful…lling ‡uctuations in the labor market based on thepresence of shopping externalities in the product market. A …rm hiring an additional workercreates positive externalities on other …rms, because buyers have more income to spend <strong>and</strong>less time to search for low prices when they are employed than when they are unemployed. Ifthese externalities are su¢ ciently strong, the employment decisions of di¤erent …rms becomestrategic complements: when one …rm increases employment, other …rms want to increasetheir employment as well, in order to take advantage of higher dem<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> higher prices inthe product market. The strategic complementarity leads to multiple rational expectationsequilibria. Equilibria di¤er with respect to the agents’expectations about future unemployment.When agents are optimistic about future unemployment, the value to a …rm from…nding an additional worker is higher, more vacancies are opened, unemployment beginsto fall, <strong>and</strong> the agents’optimistic expectations are ful…lled. When the agents’expectationsabout future unemployment become pessimistic, the economy enters a recession featuringan immediate decline in the stock market, a rapid decline in labor market tightness <strong>and</strong> aprogressive raise in unemployment. Moreover, these ‡uctuations may take place without anyconcurring change in technology.The theory is motivated by three empirical di¤erences between the shopping behaviorof employed <strong>and</strong> unemployed people. First, unemployed people spend more time shoppingthan employed people. For example, using the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), we …ndthat unemployed individuals spend between 15 <strong>and</strong> 30 percent more time shopping thanemployed individuals. Second, unemployed people pay lower prices than employed people.Using the Kielts-Nielsen Consumer Panel Data (KNCPD), we …nd that households with atleast a non-employed head pay, for exactly the same goods, between 1 <strong>and</strong> 4 percent less thanhouseholds with all heads employed. Third, unemployed people spend less than employedpeople. For example, using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), Stephens (2001)…nds that households reduce their food expenditures by approximately 15 percent whenentering unemployment because of a mass layo¤.We use search theory to build a model that captures the empirical di¤erences in theshopping behavior of employed <strong>and</strong> unemployed people. We consider an economy populatedby workers <strong>and</strong> …rms who exchange labor in a frictional market modeled as in Mortensen <strong>and</strong>Pissarides (1994), <strong>and</strong> who exchange output in a frictional market modeled as in Burdett<strong>and</strong> Judd (1983). In the labor market, vacant …rms <strong>and</strong> unemployed workers come togetherthrough a constant return to scale matching process. In equilibrium, there is unemploymentbecause the matching process is frictional, <strong>and</strong> there are income di¤erences between employed2