The CAADP Pillar I Framework

The CAADP Pillar I Framework

The CAADP Pillar I Framework

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

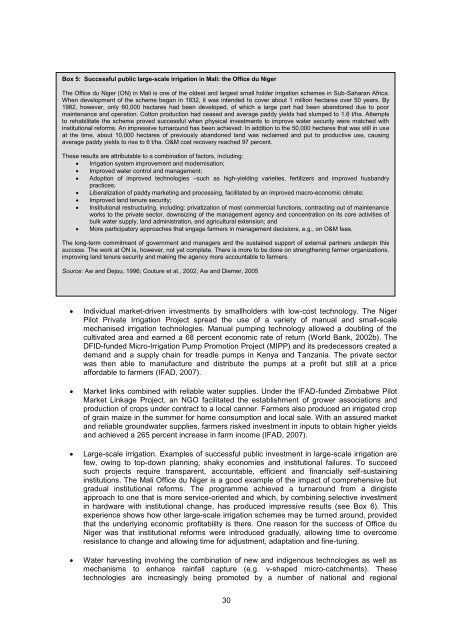

Box 5: Successful public large-scale irrigation in Mali: the Office du Niger<strong>The</strong> Office du Niger (ON) in Mali is one of the oldest and largest small holder irrigation schemes in Sub-Saharan Africa.When development of the scheme began in 1932, it was intended to cover about 1 million hectares over 50 years. By1982, however, only 60,000 hectares had been developed, of which a large part had been abandoned due to poormaintenance and operation. Cotton production had ceased and average paddy yields had slumped to 1.6 t/ha. Attemptsto rehabilitate the scheme proved successful when physical investments to improve water security were matched withinstitutional reforms. An impressive turnaround has been achieved: In addition to the 50,000 hectares that was still in useat the time, about 10,000 hectares of previously abandoned land was reclaimed and put to productive use, causingaverage paddy yields to rise to 6 t/ha. O&M cost recovery reached 97 percent.<strong>The</strong>se results are attributable to a combination of factors, including: Irrigation system improvement and modernisation; Improved water control and management; Adoption of improved technologies –such as high-yielding varieties, fertilizers and improved husbandrypractices; Liberalization of paddy marketing and processing, facilitated by an improved macro-economic climate; Improved land tenure security; Institutional restructuring, including: privatization of most commercial functions, contracting out of maintenanceworks to the private sector, downsizing of the management agency and concentration on its core activities ofbulk water supply, land administration, and agricultural extension; and More participatory approaches that engage farmers in management decisions, e.g., on O&M fees.<strong>The</strong> long-term commitment of government and managers and the sustained support of external partners underpin thissuccess. <strong>The</strong> work at ON is, however, not yet complete. <strong>The</strong>re is more to be done on strengthening farmer organizations,improving land tenure security and making the agency more accountable to farmers.Source: Aw and Dejou, 1996; Couture et al., 2002; Aw and Diemer, 2005Individual market-driven investments by smallholders with low-cost technology. <strong>The</strong> NigerPilot Private Irrigation Project spread the use of a variety of manual and small-scalemechanised irrigation technologies. Manual pumping technology allowed a doubling of thecultivated area and earned a 68 percent economic rate of return (World Bank, 2002b). <strong>The</strong>DFID-funded Micro-Irrigation Pump Promotion Project (MIPP) and its predecessors created ademand and a supply chain for treadle pumps in Kenya and Tanzania. <strong>The</strong> private sectorwas then able to manufacture and distribute the pumps at a profit but still at a priceaffordable to farmers (IFAD, 2007).Market links combined with reliable water supplies. Under the IFAD-funded Zimbabwe PilotMarket Linkage Project, an NGO facilitated the establishment of grower associations andproduction of crops under contract to a local canner. Farmers also produced an irrigated cropof grain maize in the summer for home consumption and local sale. With an assured marketand reliable groundwater supplies, farmers risked investment in inputs to obtain higher yieldsand achieved a 265 percent increase in farm income (IFAD, 2007).Large-scale irrigation. Examples of successful public investment in large-scale irrigation arefew, owing to top-down planning, shaky economies and institutional failures. To succeedsuch projects require transparent, accountable, efficient and financially self-sustaininginstitutions. <strong>The</strong> Mali Office du Niger is a good example of the impact of comprehensive butgradual institutional reforms. <strong>The</strong> programme achieved a turnaround from a dirigisteapproach to one that is more service-oriented and which, by combining selective investmentin hardware with institutional change, has produced impressive results (see Box 6). Thisexperience shows how other large-scale irrigation schemes may be turned around, providedthat the underlying economic profitability is there. One reason for the success of Office duNiger was that institutional reforms were introduced gradually, allowing time to overcomeresistance to change and allowing time for adjustment, adaptation and fine-tuning.Water harvesting involving the combination of new and indigenous technologies as well asmechanisms to enhance rainfall capture (e.g. v-shaped micro-catchments). <strong>The</strong>setechnologies are increasingly being promoted by a number of national and regional30