Read the full report - Danish Refugee Council

Read the full report - Danish Refugee Council

Read the full report - Danish Refugee Council

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

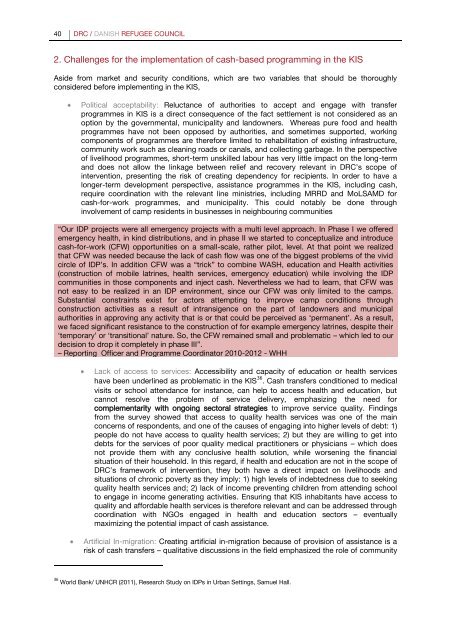

40 DRC / DANISH REFUGEE COUNCIL2. Challenges for <strong>the</strong> implementation of cash-based programming in <strong>the</strong> KISAside from market and security conditions, which are two variables that should be thoroughlyconsidered before implementing in <strong>the</strong> KIS,Political acceptability: Reluctance of authorities to accept and engage with transferprogrammes in KIS is a direct consequence of <strong>the</strong> fact settlement is not considered as anoption by <strong>the</strong> governmental, municipality and landowners. Whereas pure food and healthprogrammes have not been opposed by authorities, and sometimes supported, workingcomponents of programmes are <strong>the</strong>refore limited to rehabilitation of existing infrastructure,community work such as cleaning roads or canals, and collecting garbage. In <strong>the</strong> perspectiveof livelihood programmes, short-term unskilled labour has very little impact on <strong>the</strong> long-termand does not allow <strong>the</strong> linkage between relief and recovery relevant in DRC’s scope ofintervention, presenting <strong>the</strong> risk of creating dependency for recipients. In order to have alonger-term development perspective, assistance programmes in <strong>the</strong> KIS, including cash,require coordination with <strong>the</strong> relevant line ministries, including MRRD and MoLSAMD forcash-for-work programmes, and municipality. This could notably be done throughinvolvement of camp residents in businesses in neighbouring communities“Our IDP projects were all emergency projects with a multi level approach. In Phase I we offeredemergency health, in kind distributions, and in phase II we started to conceptualize and introducecash-for-work (CFW) opportunities on a small-scale, ra<strong>the</strong>r pilot, level. At that point we realizedthat CFW was needed because <strong>the</strong> lack of cash flow was one of <strong>the</strong> biggest problems of <strong>the</strong> vividcircle of IDP’s. In addition CFW was a “trick” to combine WASH, education and Health activities(construction of mobile latrines, health services, emergency education) while involving <strong>the</strong> IDPcommunities in those components and inject cash. Never<strong>the</strong>less we had to learn, that CFW wasnot easy to be realized in an IDP environment, since our CFW was only limited to <strong>the</strong> camps.Substantial constraints exist for actors attempting to improve camp conditions throughconstruction activities as a result of intransigence on <strong>the</strong> part of landowners and municipalauthorities in approving any activity that is or that could be perceived as ‘permanent’. As a result,we faced significant resistance to <strong>the</strong> construction of for example emergency latrines, despite <strong>the</strong>ir‘temporary’ or ‘transitional’ nature. So, <strong>the</strong> CFW remained small and problematic – which led to ourdecision to drop it completely in phase III”.– Reporting Officer and Programme Coordinator 2010-2012 - WHHLack of access to services: Accessibility and capacity of education or health serviceshave been underlined as problematic in <strong>the</strong> KIS 36 . Cash transfers conditioned to medicalvisits or school attendance for instance, can help to access health and education, butcannot resolve <strong>the</strong> problem of service delivery, emphasizing <strong>the</strong> need forcomplementarity with ongoing sectoral strategies to improve service quality. Findingsfrom <strong>the</strong> survey showed that access to quality health services was one of <strong>the</strong> mainconcerns of respondents, and one of <strong>the</strong> causes of engaging into higher levels of debt: 1)people do not have access to quality health services; 2) but <strong>the</strong>y are willing to get intodebts for <strong>the</strong> services of poor quality medical practitioners or physicians – which doesnot provide <strong>the</strong>m with any conclusive health solution, while worsening <strong>the</strong> financialsituation of <strong>the</strong>ir household. In this regard, if health and education are not in <strong>the</strong> scope ofDRC’s framework of intervention, <strong>the</strong>y both have a direct impact on livelihoods andsituations of chronic poverty as <strong>the</strong>y imply: 1) high levels of indebtedness due to seekingquality health services and; 2) lack of income preventing children from attending schoolto engage in income generating activities. Ensuring that KIS inhabitants have access toquality and affordable health services is <strong>the</strong>refore relevant and can be addressed throughcoordination with NGOs engaged in health and education sectors – eventuallymaximizing <strong>the</strong> potential impact of cash assistance.Artificial In-migration: Creating artificial in-migration because of provision of assistance is arisk of cash transfers – qualitative discussions in <strong>the</strong> field emphasized <strong>the</strong> role of community36 World Bank/ UNHCR (2011), Research Study on IDPs in Urban Settings, Samuel Hall.