Political Corruption in America: A Search for Definitions ... - See also

Political Corruption in America: A Search for Definitions ... - See also

Political Corruption in America: A Search for Definitions ... - See also

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

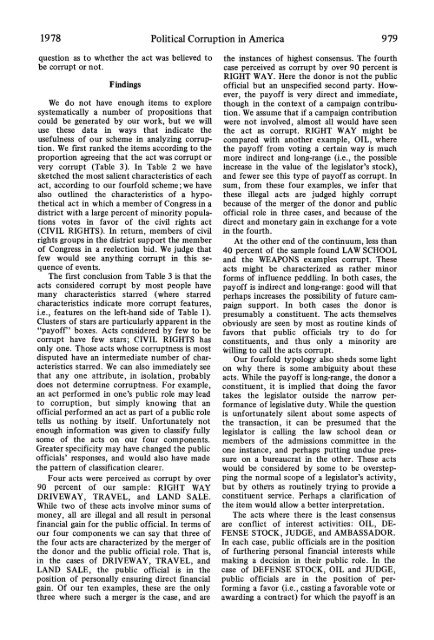

1978 <strong>Political</strong> <strong>Corruption</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>America</strong> 979question as to whether the act was believed tobe corrupt or not.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsWe do not have enough items to exploresystematically a number of propositions thatcould be generated by our work, but we willuse these data <strong>in</strong> ways that <strong>in</strong>dicate theusefulness of our scheme <strong>in</strong> analyz<strong>in</strong>g corruption.We first ranked the items accord<strong>in</strong>g to theproportion agree<strong>in</strong>g that the act was corrupt orvery corrupt (Table 3). In Table 2 we havesketched the most salient characteristics of eachact, accord<strong>in</strong>g to our fourfold scheme; we have<strong>also</strong> outl<strong>in</strong>ed the characteristics of a hypotheticalact <strong>in</strong> which a member of Congress <strong>in</strong> adistrict with a large percent of m<strong>in</strong>ority populationsvotes <strong>in</strong> favor of the civil rights act(CIVIL RIGHTS). In return, members of civilrights groups <strong>in</strong> the district support the memberof Congress <strong>in</strong> a reelection bid. We judge thatfew would see anyth<strong>in</strong>g corrupt <strong>in</strong> this sequenceof events.The first conclusion from Table 3 is that theacts considered corrupt by most people havemany characteristics starred (where starredcharacteristics <strong>in</strong>dicate more corrupt features,i.e., features on the left-hand side of Table 1).Clusters of stars are particularly apparent <strong>in</strong> the"payoff" boxes. Acts considered by few to becorrupt have few stars; CIVIL RIGHTS hasonly one. Those acts whose corruptness is mostdisputed have an <strong>in</strong>termediate number of characteristicsstarred. We can <strong>also</strong> immediately seethat any one attribute, <strong>in</strong> isolation, probablydoes not determ<strong>in</strong>e corruptness. For example,an act per<strong>for</strong>med <strong>in</strong> one's public role may leadto corruption, but simply know<strong>in</strong>g that anofficial per<strong>for</strong>med an act as part of a public roletells us noth<strong>in</strong>g by itself. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately notenough <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation was given to classify fullysome of the acts on our four components.Greater specificity may have changed the publicofficials' responses, and would <strong>also</strong> have madethe pattern of classification clearer.Four acts were perceived as corrupt by over90 percent of our sample: RIGHT WAYDRIVEWAY, TRAVEL, and LAND SALE.While two of these acts <strong>in</strong>volve m<strong>in</strong>or sums ofmoney, all are illegal and all result <strong>in</strong> personalf<strong>in</strong>ancial ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>for</strong> the public official. In terms ofour four components we can say that three ofthe four acts are characterized by the merger ofthe donor and the public official role. That is,<strong>in</strong> the cases of DRIVEWAY, TRAVEL, andLAND SALE, the public official is <strong>in</strong> theposition of personally ensur<strong>in</strong>g direct f<strong>in</strong>ancialga<strong>in</strong>. Of our ten examples, these are the onlythree where such a merger is the case, and arethe <strong>in</strong>stances of highest consensus. The fourthcase perceived as corrupt by over 90 percent isRIGHT WAY. Here the donor is not the publicofficial but an unspecified second party. However,the payoff is very direct and immediate,though <strong>in</strong> the context of a campaign contribution.We assume that if a campaign contributionwere not <strong>in</strong>volved, almost all would have seenthe act as corrupt. RIGHT WAY might becompared with another example, OIL, wherethe payoff from vot<strong>in</strong>g a certa<strong>in</strong> way is muchmore <strong>in</strong>direct and long-range (i.e., the possible<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> the value of the legislator's stock),and fewer see this type of payoff as corrupt. Insum, from these four examples, we <strong>in</strong>fer thatthese illegal acts are judged highly corruptbecause of the merger of the donor and publicofficial role <strong>in</strong> three cases, and because of thedirect and monetary ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> exchange <strong>for</strong> a vote<strong>in</strong> the fourth.At the other end of the cont<strong>in</strong>uum, less than40 percent of the sample found LAW SCHOOLand the WEAPONS examples corrupt. Theseacts might be characterized as rather m<strong>in</strong>or<strong>for</strong>ms of <strong>in</strong>fluence peddl<strong>in</strong>g. In both cases, thepayoff is <strong>in</strong>direct and long-range: good will thatperhaps <strong>in</strong>creases the possibility of future campaignsupport. In both cases the donor ispresumably a constituent. The acts themselvesobviously are seen by most as rout<strong>in</strong>e k<strong>in</strong>ds offavors that public officials try to do <strong>for</strong>constituents, and thus only a m<strong>in</strong>ority areWill<strong>in</strong>g to call the acts corrupt.Our fourfold typology <strong>also</strong> sheds some lighton why there is some ambiguity about theseacts. While the payoff is long-range, the donor aconstituent, it is implied that do<strong>in</strong>g the favortakes the legislator outside the narrow per<strong>for</strong>manceof legislative duty. While the questionis un<strong>for</strong>tunately silent about some aspects ofthe transaction, it can be presumed that thelegislator is call<strong>in</strong>g the law school dean ormembers of the admissions committee <strong>in</strong> theone <strong>in</strong>stance, and perhaps putt<strong>in</strong>g undue pressureon a bureaucrat <strong>in</strong> the other. These actswould be considered by some to be overstepp<strong>in</strong>gthe normal scope of a legislator's activity,but by others as rout<strong>in</strong>ely try<strong>in</strong>g to provide aconstituent service. Perhaps a clarification ofthe item would allow a better <strong>in</strong>terpretation.The acts where there is the least consensusare conflict of <strong>in</strong>terest activities: OIL, DE-FENSE STOCK, JUDGE, and AMBASSADOR.In each case, public officials are <strong>in</strong> the positionof further<strong>in</strong>g personal f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>terests whilemak<strong>in</strong>g a decision <strong>in</strong> their public role. In thecase of DEFENSE STOCK, OIL and JUDGE,public officials are <strong>in</strong> the position of per<strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>ga favor (i.e., cast<strong>in</strong>g a favorable vote oraward<strong>in</strong>g a contract) <strong>for</strong> which the payoff is an