U. Bellugi et al. (1999) - Duke-UNC Brain Imaging and Analysis Center

U. Bellugi et al. (1999) - Duke-UNC Brain Imaging and Analysis Center

U. Bellugi et al. (1999) - Duke-UNC Brain Imaging and Analysis Center

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

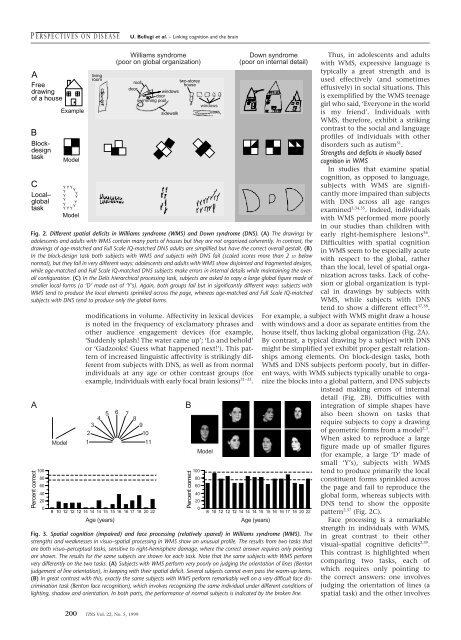

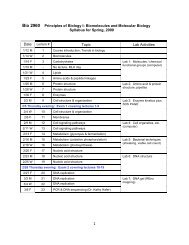

P ERSPECTIVES ON DISEASEU. <strong>Bellugi</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. – Linking cognition <strong>and</strong> the brainAFreedrawingof a houseBBlockdesigntaskCLoc<strong>al</strong>–glob<strong>al</strong>taskExampleModelYYYY YYYYYYY YY Y YModellivingroomWilliams syndrome(poor on glob<strong>al</strong> organization)roofdoorwindowsdoorswimming poolsidew<strong>al</strong>ktwo-storeyhousewindowsmodifications in volume. Affectivity in lexic<strong>al</strong> devicesis noted in the frequency of exclamatory phrases <strong>and</strong>other audience engagement devices (for example,‘Suddenly splash! The water came up’; ‘Lo <strong>and</strong> behold’or ‘Gadzooks! Guess what happened next!’). This patternof increased linguistic affectivity is strikingly differentfrom subjects with DNS, as well as from norm<strong>al</strong>individu<strong>al</strong>s at any age or other contrast groups (forexample, individu<strong>al</strong>s with early foc<strong>al</strong> brain lesions) 31–33 .Thus, in adolescents <strong>and</strong> adultswith WMS, expressive language istypic<strong>al</strong>ly a great strength <strong>and</strong> isused effectively (<strong>and</strong> som<strong>et</strong>imeseffusively) in soci<strong>al</strong> situations. Thisis exemplified by the WMS teenagegirl who said, ‘Everyone in the worldis my friend’. Individu<strong>al</strong>s withWMS, therefore, exhibit a strikingcontrast to the soci<strong>al</strong> <strong>and</strong> languageprofiles of individu<strong>al</strong>s with otherdisorders such as autism 31 .Strengths <strong>and</strong> deficits in visu<strong>al</strong>ly basedcognition in WMSIn studies that examine spati<strong>al</strong>cognition, as opposed to language,subjects with WMS are significantlymore impaired than subjectswith DNS across <strong>al</strong>l age rangesexamined 3,34,35 . Indeed, individu<strong>al</strong>swith WMS performed more poorlyin our studies than children withearly right-hemisphere lesions 36 .Difficulties with spati<strong>al</strong> cognitionin WMS seem to be especi<strong>al</strong>ly acutewith respect to the glob<strong>al</strong>, ratherthan the loc<strong>al</strong>, level of spati<strong>al</strong> organizationacross tasks. Lack of cohesionor glob<strong>al</strong> organization is typic<strong>al</strong>in drawings by subjects withWMS, while subjects with DNStend to show a different effect 37,38 .For example, a subject with WMS might draw a housewith windows <strong>and</strong> a door as separate entities from thehouse itself, thus lacking glob<strong>al</strong> organization (Fig. 2A).By contrast, a typic<strong>al</strong> drawing by a subject with DNSmight be simplified y<strong>et</strong> exhibit proper gest<strong>al</strong>t relationshipsamong elements. On block-design tasks, bothWMS <strong>and</strong> DNS subjects perform poorly, but in differentways, with WMS subjects typic<strong>al</strong>ly unable to organiz<strong>et</strong>he blocks into a glob<strong>al</strong> pattern, <strong>and</strong> DNS subjectsinstead making errors of intern<strong>al</strong>d<strong>et</strong>ail (Fig. 2B). Difficulties withintegration of simple shapes have<strong>al</strong>so been shown on tasks thatrequire subjects to copy a drawingof geom<strong>et</strong>ric forms from a model 2,3 .When asked to reproduce a largefigure made up of sm<strong>al</strong>ler figures(for example, a large ‘D’ made ofsm<strong>al</strong>l ‘Y’s), subjects with WMStend to produce primarily the loc<strong>al</strong>constituent forms sprinkled acrossthe page <strong>and</strong> fail to reproduce theglob<strong>al</strong> form, whereas subjects withDNS tend to show the oppositeDown syndrome(poor on intern<strong>al</strong> d<strong>et</strong>ail)Fig. 2. Different spati<strong>al</strong> deficits in Williams syndrome (WMS) <strong>and</strong> Down syndrome (DNS). (A) The drawings byadolescents <strong>and</strong> adults with WMS contain many parts of houses but they are not organized coherently. In contrast, thedrawings of age-matched <strong>and</strong> Full Sc<strong>al</strong>e IQ-matched DNS adults are simplified but have the correct over<strong>al</strong>l gest<strong>al</strong>t. (B)In the block-design task both subjects with WMS <strong>and</strong> subjects with DNS fail (sc<strong>al</strong>ed scores more than 2 SD belownorm<strong>al</strong>), but they fail in very different ways: adolescents <strong>and</strong> adults with WMS show disjointed <strong>and</strong> fragmented designs,while age-matched <strong>and</strong> Full Sc<strong>al</strong>e IQ-matched DNS subjects make errors in intern<strong>al</strong> d<strong>et</strong>ails while maintaining the over<strong>al</strong>lconfiguration. (C) In the Delis hierarchic<strong>al</strong> processing task, subjects are asked to copy a large glob<strong>al</strong> figure made ofsm<strong>al</strong>ler loc<strong>al</strong> forms (a ‘D’ made out of ‘Y’s). Again, both groups fail but in significantly different ways: subjects withWMS tend to produce the loc<strong>al</strong> elements sprinkled across the page, whereas age-matched <strong>and</strong> Full Sc<strong>al</strong>e IQ-matchedsubjects with DNS tend to produce only the glob<strong>al</strong> forms.APercent correct10080604020064 53789Model2110118 10 12 12 12 14 14 14 15 15 16 16 17 18 20 22Age (years)BPercent correct100Model8060402008 10 12 12 12 14 14 14 15 15 16 16 17 18 20 22Age (years)Fig. 3. Spati<strong>al</strong> cognition (impaired) <strong>and</strong> face processing (relatively spared) in Williams syndrome (WMS). Thestrengths <strong>and</strong> weaknesses in visuo–spati<strong>al</strong> processing in WMS show an unusu<strong>al</strong> profile. The results from two tasks thatare both visuo–perceptu<strong>al</strong> tasks, sensitive to right-hemisphere damage, where the correct answer requires only pointingare shown. The results for the same subjects are shown for each task. Note that the same subjects with WMS performvery differently on the two tasks. (A) Subjects with WMS perform very poorly on judging the orientation of lines (Bentonjudgement of line orientation), in keeping with their spati<strong>al</strong> deficit. Sever<strong>al</strong> subjects cannot even pass the warm-up items.(B) In great contrast with this, exactly the same subjects with WMS perform remarkably well on a very difficult face discriminationtask (Benton face recognition), which involves recognizing the same individu<strong>al</strong> under different conditions oflighting, shadow <strong>and</strong> orientation. In both parts, the performance of norm<strong>al</strong> subjects is indicated by the broken line.pattern 2,37 (Fig. 2C).Face processing is a remarkablestrength in individu<strong>al</strong>s with WMS,in great contrast to their othervisu<strong>al</strong>–spati<strong>al</strong> cognitive deficits 2,39 .This contrast is highlighted whencomparing two tasks, each ofwhich requires only pointing tothe correct answers: one involvesjudging the orientation of lines (aspati<strong>al</strong> task) <strong>and</strong> the other involves200 TINS Vol. 22, No. 5, <strong>1999</strong>