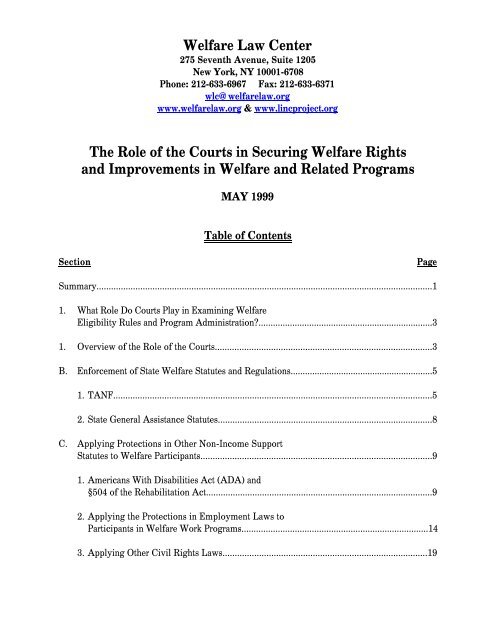

The Role of the Courts in Securing Welfare Rights and ...

The Role of the Courts in Securing Welfare Rights and ...

The Role of the Courts in Securing Welfare Rights and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

SectionPageD. <strong>Role</strong> <strong>of</strong> Federal Constitution..................................................................................................231. Equal Protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Laws.............................................................................................242. Due Process <strong>and</strong> Fair Procedures.......................................................................................283. Right to Privacy <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Home Does Not BlockAll Home Visits..................................................................................................................345. Are <strong>Courts</strong> Likely to F<strong>in</strong>d that Government Hasan Affirmative Duty to Provide <strong>Welfare</strong>?..............................................................................35II.Assur<strong>in</strong>g that Low-Income Individuals Get Accessto Benefits from Related Income Support Programs..............................................................39A. Food Stamps <strong>and</strong> Medicaid....................................................................................................40B. Assur<strong>in</strong>g Access to Child Care...............................................................................................43III. O<strong>the</strong>r Emerg<strong>in</strong>g Issues............................................................................................................47A. <strong>Welfare</strong> Organizers’ <strong>Rights</strong> to Access to <strong>Welfare</strong> Offices......................................................47B. Privatization <strong>of</strong> <strong>Welfare</strong> Eligibility Determ<strong>in</strong>ationsthrough Contract<strong>in</strong>g with Non-Pr<strong>of</strong>its, Private Companies<strong>and</strong> Religious Institutions.......................................................................................................50C. Involvement <strong>of</strong> Religious Institutions <strong>in</strong> Provid<strong>in</strong>gSocial Services.........................................................................................................................54D. Obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Information from State Agencies...........................................................................55IV. Identify<strong>in</strong>g Legal Resources for <strong>Welfare</strong> Litigation................................................................56Endnotes.........................................................................................................................................58May 1999⋅ ii ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerproviders can also work creatively with federally-funded legal services programs to make surethat clients have available <strong>the</strong> full range <strong>of</strong> legal representation. Organiz<strong>in</strong>g by low <strong>in</strong>come groupsis on <strong>the</strong> rise as <strong>the</strong>se groups work to address time limits, workfare, excessive sanctions, <strong>the</strong> needfor adequate safety net programs, liv<strong>in</strong>g wage employment, <strong>and</strong> supports for work, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gchild care, health <strong>in</strong>surance, <strong>and</strong> transportation. Advocates have <strong>the</strong> opportunity to work closelywith such groups to make litigation part <strong>of</strong> broader campaigns for programs that respond tocommunity needs.<strong>The</strong> paper, which explores <strong>the</strong>se <strong>the</strong>mes <strong>in</strong> more detail, is organized <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>gsections:Section I exam<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> courts <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g welfare program rules <strong>and</strong>adm<strong>in</strong>istration. It <strong>in</strong>cludes an extensive discussion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> various sources <strong>of</strong> law that mayprotect welfare claimants.Section II discusses issues aris<strong>in</strong>g under several key <strong>in</strong>come support programs, namelyMedicaid, Food Stamps, <strong>and</strong> child care, that are important for TANF recipients as well as forthose enter<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> seek<strong>in</strong>g to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> employment.Section III reviews, <strong>in</strong> somewhat briefer detail, several issues that are emerg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> light <strong>of</strong>welfare devolution <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> legal questions <strong>the</strong>y present. <strong>The</strong>se issues are access to welfare<strong>of</strong>fices, privatization <strong>of</strong> welfare eligibility determ<strong>in</strong>ations, <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>of</strong> religious groups <strong>in</strong>provid<strong>in</strong>g social services, <strong>and</strong> obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation from state agencies.Section IV highlights <strong>the</strong> challenge <strong>of</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g legal resources for welfare litigation.I. What <strong>Role</strong> Do <strong>Courts</strong> Play <strong>in</strong> Exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>Welfare</strong> Eligibility Rules <strong>and</strong> ProgramAdm<strong>in</strong>istration?A. Overview <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Role</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Courts</strong>May 1999⋅ 3 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center<strong>Courts</strong> have a limited but important role to play <strong>in</strong> secur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> enforc<strong>in</strong>g rights <strong>of</strong> publicbenefits <strong>and</strong> fair adm<strong>in</strong>istration. On <strong>the</strong> positive side, courts can enforce exist<strong>in</strong>g statutory law,that is <strong>the</strong>y can require compliance with exist<strong>in</strong>g welfare law <strong>and</strong> decide how o<strong>the</strong>r laws, e.g. civilrights laws <strong>and</strong> employment laws, apply to welfare recipients <strong>and</strong> welfare programs. <strong>Courts</strong> canalso serve as a check on arbitrary governmental action by enforc<strong>in</strong>g constitutional guarantees suchas due process <strong>and</strong> equal protection guarantees, <strong>in</strong> limited situations. <strong>Courts</strong> will not assume alegislative role <strong>and</strong> create broad new welfare rights. Instead, <strong>the</strong>y will generally defer policydecisions to legislatures <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> some <strong>in</strong>stances to adm<strong>in</strong>istrative agencies.Advocates <strong>and</strong> organizers can maximize <strong>the</strong> effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir work through strategicchoices as to when <strong>and</strong> how to use <strong>the</strong> courts to raise key social <strong>and</strong> economic justice issues.Litigation can <strong>and</strong> has been an important part <strong>of</strong> broad-based campaigns with o<strong>the</strong>r allies t<strong>of</strong>ur<strong>the</strong>r such goals as assur<strong>in</strong>g adequate benefits, promot<strong>in</strong>g treatment <strong>of</strong> workfare workers aso<strong>the</strong>r workers, <strong>and</strong> assur<strong>in</strong>g fair program adm<strong>in</strong>istration. While <strong>the</strong> goal <strong>of</strong> litigation is generally tostop unfair practices or extend rights, litigation can also serve <strong>the</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> heighten<strong>in</strong>gawareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> harms <strong>of</strong> welfare policies, even if <strong>the</strong> court rules unfavorably. Recentorganiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> litigation around workfare <strong>in</strong> New York City provide examples <strong>of</strong> concertedefforts to address such critical issues as allow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals to pursue education <strong>in</strong>stead <strong>of</strong>workfare, prevent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>appropriate assignments <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals with disabilities to workfare, <strong>and</strong>secur<strong>in</strong>g fair treatment <strong>of</strong> workfare workers by us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> prevail<strong>in</strong>g ra<strong>the</strong>r than m<strong>in</strong>imum wage tocalculate workfare hours <strong>and</strong> by apply<strong>in</strong>g health <strong>and</strong> safety protections to workfareassignments. 1A campaign dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> mid-1980's when Massachusetts low-<strong>in</strong>come groups <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>irallies organized to <strong>in</strong>crease AFDC benefits dur<strong>in</strong>g a period <strong>of</strong> grow<strong>in</strong>g public awareness <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>problems <strong>of</strong> homelessness provides ano<strong>the</strong>r example <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> complementary role <strong>of</strong> organiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>litigation. <strong>The</strong> campaign focused <strong>in</strong>itially on state legislators <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r op<strong>in</strong>ion makers. Itsubsequently adopted a litigation strategy based on state law that low <strong>in</strong>come groups <strong>and</strong>advocates hoped would support <strong>the</strong> effort to get <strong>the</strong> legislature to raise benefits. <strong>The</strong> caseMay 1999⋅ 4 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerresulted <strong>in</strong> a unanimous decision by <strong>the</strong> state Supreme Court requir<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> agency to update itsneed st<strong>and</strong>ard annually <strong>and</strong> request <strong>the</strong> legislature to take appropriate action <strong>the</strong>reby creat<strong>in</strong>g amechanism for regular attention by <strong>the</strong> legislature to <strong>the</strong> issue. 2With <strong>the</strong> 1986 elim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> federal AFDC law <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual rights provided underthat law, <strong>the</strong> legal l<strong>and</strong>scape has dramatically changed. Advocates will now look to state law <strong>and</strong>state courts to def<strong>in</strong>e welfare rights. New litigation opportunities <strong>and</strong> challenges will arise, but itis too soon to predict how courts will respond. With welfare programs’ emphasis on workactivities, <strong>the</strong>re will be efforts to extend <strong>the</strong> protections <strong>of</strong> employment <strong>and</strong> civil rights laws forwelfare program participants. Due process questions have begun to arise, <strong>and</strong> courts will beasked to address <strong>the</strong>se issues. In limited situations courts may f<strong>in</strong>d that policies or practicesviolate rights to equal protection.<strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g discussion reviews issues related to <strong>the</strong> enforcement <strong>of</strong> state welfare laws,<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Americans with Disabilities Act, employment laws, <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r civilrights laws to welfare claimants. It <strong>the</strong>n exam<strong>in</strong>es <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> federal constitution, with afocus on equal protection <strong>and</strong> due process. F<strong>in</strong>ally, <strong>the</strong> discussion addresses whe<strong>the</strong>r courts arelikely to impose an affirmative duty to provide assistance <strong>and</strong> comments on <strong>the</strong> view <strong>of</strong> legalscholars who have analyzed this question <strong>in</strong> light <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> provisions <strong>of</strong> state constitutions <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>ternational law.B. Enforcement <strong>of</strong> State <strong>Welfare</strong> Statutes <strong>and</strong> Regulations1. TANFBefore <strong>the</strong> 1996 federal welfare law 3 repealed AFDC, welfare applicants <strong>and</strong> recipientsfrequently went to court to challenge abusive state welfare policies <strong>and</strong> practices as contrary to<strong>the</strong> federal AFDC statute <strong>and</strong> regulations, <strong>and</strong> many important victories were won. For example,U.S. Supreme Court decisions established that states were required to provide aid to thoseMay 1999⋅ 5 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centereligible under federal st<strong>and</strong>ards. 4 Federal regulations were used successfully <strong>in</strong> many cases toattack abusive eligibility verification practices <strong>and</strong> excessive applications process delays. 5 Needyfamilies could br<strong>in</strong>g court cases based on federal AFDC law because <strong>the</strong> federal statute, 42 U.S.C.602 (a)(10), gave <strong>in</strong>dividuals an entitlement to aid <strong>and</strong> provided <strong>the</strong> federal match<strong>in</strong>g funds toback up that entitlement. Of course, because <strong>the</strong> former AFDC program was a federal-stateprogram, states also had <strong>the</strong>ir own welfare statutes. However, litigation typically focused onenforc<strong>in</strong>g federal requirements, ra<strong>the</strong>r than state law. 6 Generally federal courts were considered afriendlier forum than state courts, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re was a body <strong>of</strong> uniform federal law on whichadvocates could rely.<strong>The</strong> federal law establish<strong>in</strong>g TANF, <strong>the</strong> block grant program that replaced AFDC,elim<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>the</strong> federal guarantee <strong>of</strong> aid to <strong>in</strong>dividuals. 7 <strong>The</strong> federal law also gives states broaddiscretion to design welfare programs <strong>and</strong> at <strong>the</strong> same time limits that discretion <strong>in</strong> key areas,notably by requir<strong>in</strong>g time limits on an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s receipt <strong>of</strong> federal aid <strong>and</strong> impos<strong>in</strong>g strict workrequirements.In light <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se changes <strong>in</strong> federal welfare law, a family’s rights to welfare benefits arenow def<strong>in</strong>ed under state law <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals must look primarily to <strong>the</strong>se state welfare laws,which vary from state to state, to determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir rights. In addition, <strong>in</strong> some stateswhich have delegated decisionmak<strong>in</strong>g to localities, <strong>the</strong>re may not even be state law to enforce.Advocates may have to explore local law.<strong>The</strong>re has not yet been extensive litigation seek<strong>in</strong>g to enforce state TANF laws, but <strong>the</strong>litigation to date has primarily <strong>in</strong>volved work program requirements <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> fair hear<strong>in</strong>gs system(as to <strong>the</strong> latter see also <strong>the</strong> due process discussion, below). Examples <strong>of</strong> recent litigationenforc<strong>in</strong>g state welfare laws (under both TANF <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> former AFDC program) <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong>follow<strong>in</strong>g:TANF Litigation:Davila v. Hammons (New York). 8 This case is based on state welfare law <strong>and</strong> challengesNew York City’s practice <strong>of</strong> assign<strong>in</strong>g recipients to unpaid workfare without do<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>dividualMay 1999⋅ 6 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerassessment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> recipient’s educational <strong>and</strong> vocational history <strong>and</strong> needs. <strong>The</strong> court has ruledfor <strong>the</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs so far. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center is co-counsel with o<strong>the</strong>rs.Brukhman v. Giuliani (New York). 9 This case challenges New York City’s practice <strong>of</strong>fail<strong>in</strong>g to compute workfare hours at prevail<strong>in</strong>g wage rates ra<strong>the</strong>r than m<strong>in</strong>imum wage rates. <strong>The</strong>case raises state statutory claims as well as o<strong>the</strong>r claims, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a state constitutional claim.After <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial successful decision, <strong>the</strong> legislature elim<strong>in</strong>ated <strong>the</strong> prevail<strong>in</strong>g wage provision <strong>and</strong><strong>the</strong> appellate court accord<strong>in</strong>gly reversed <strong>the</strong> favorable lower court decision. <strong>The</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs areappeal<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center is co-counsel with o<strong>the</strong>rs.Capers v. Giuliani (New York). 10 This case challenged New York City’s failure toprovide basic health <strong>and</strong> safety protections to workfare workers. Claims were based on statewelfare law provisions provid<strong>in</strong>g for assignments to workfare positions only if health <strong>and</strong> safetyst<strong>and</strong>ards are met (o<strong>the</strong>r claims were raised as well). Follow<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>itial victory <strong>the</strong> statelegislature enacted legislation provid<strong>in</strong>g that workfare workers are covered under <strong>the</strong> lawprotect<strong>in</strong>g public employees. Based on this change <strong>the</strong> appellate reversed <strong>the</strong> lower court’s order.<strong>The</strong> Court <strong>of</strong> Appeals subsequently decl<strong>in</strong>ed to hear an appeal. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center wasco-counsel with o<strong>the</strong>rs.<strong>The</strong>se cases are all part <strong>of</strong> a broader organiz<strong>in</strong>g strategy to secure worker protections. 11Piron v. W<strong>in</strong>g (New York). 12 This case seeks to enforce state law requir<strong>in</strong>g hear<strong>in</strong>gs tobe issued <strong>and</strong> implemented with<strong>in</strong> 90 says <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> hear<strong>in</strong>g request. <strong>The</strong> court has grantedprelim<strong>in</strong>ary relief for pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervenors.State <strong>of</strong> New Mexico ex rel Taylor v. Johnson (New Mexico). 13 This case successfullychallenged <strong>the</strong> Governor’s attempts to implement his own version <strong>of</strong> welfare reform after <strong>the</strong>state legislature failed to pass new welfare legislation. <strong>The</strong> court ruled that <strong>the</strong> Governor hadexceeded his authority under <strong>the</strong> state constitution <strong>and</strong> that he must comply with exist<strong>in</strong>g statewelfare law.Thibault v. Department <strong>of</strong> Transitional Assistance (Massachusetts). 14 This challenge to<strong>the</strong> process by which <strong>the</strong> state makes disability determ<strong>in</strong>ations for TANF <strong>and</strong> Emergency AidMay 1999⋅ 7 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerraises claims under state law, <strong>the</strong> Americans With Disabilities Act, <strong>and</strong> Title VI <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Civil<strong>Rights</strong> Act. <strong>The</strong> court has granted prelim<strong>in</strong>ary relief f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that denial <strong>of</strong> a disability exemptionto those who did not respond to a letter from <strong>the</strong> private contractor responsible for mak<strong>in</strong>gdeterm<strong>in</strong>ations was arbitrary <strong>and</strong> unreasonable <strong>in</strong> violation <strong>of</strong> state law requir<strong>in</strong>g that welfareadm<strong>in</strong>istration be fair <strong>and</strong> equitable. <strong>The</strong> court found that <strong>the</strong> letter was technical, confus<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong>difficult to underst<strong>and</strong>, complete <strong>and</strong> return <strong>and</strong> that it required an educational level higher thanthat <strong>of</strong> most recipients.Smith v. McIntire (Massachusetts). 15 This case challenges <strong>the</strong> denial <strong>of</strong> earn<strong>in</strong>gsdisregards <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g eligibility for <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> amount <strong>of</strong> grant extensions for families that haveexhausted <strong>the</strong>ir state 24-month TANF time limit. <strong>The</strong> court ruled that <strong>the</strong> state regulations are <strong>in</strong>conflict with <strong>the</strong> state welfare statute which requires <strong>the</strong> disregards.AFDC Litigation:Massachusetts Coalition for <strong>the</strong> Homeless v. Secretary <strong>of</strong> Human Services(Massachusetts). 16 This litigation was part <strong>of</strong> an extensive campaign to <strong>in</strong>crease AFDC benefitlevels. In this 1987 decision <strong>the</strong> Massachusetts court ruled that a state statute required thatAFDC benefit levels be sufficient to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> families <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir own homes <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>refore required<strong>the</strong> agency to 1) seek to prevent homelessness by provid<strong>in</strong>g sufficient bene fits or by o<strong>the</strong>rmeans; <strong>and</strong> 2) notify <strong>the</strong> legislature when appropriations were not sufficient to meet this duty.Although <strong>the</strong> court did not order <strong>the</strong> defendants to pay <strong>in</strong>creased benefits (a decision for <strong>the</strong>legislature), it did order <strong>the</strong>m to update <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>of</strong> adequacy annually <strong>and</strong> to ask <strong>the</strong>legislature to address <strong>the</strong> issues through appropriations or o<strong>the</strong>r means.2. State General Assistance StatutesGeneral Assistance (GA) programs are established under state, not federal law, <strong>and</strong>litigation has sought to enforce <strong>the</strong>se <strong>and</strong> related provisions <strong>in</strong> state law. 17 Some recent examples<strong>in</strong>clude:May 1999⋅ 8 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law CenterCorreia v. Department <strong>of</strong> Public <strong>Welfare</strong> (Massachusetts). 18 This case challenged <strong>the</strong>large number <strong>of</strong> technical denials that resulted when <strong>the</strong> state replaced GA with an emergency aidprogram. <strong>The</strong> court found that <strong>the</strong> agency’s practices violated a state statute requir<strong>in</strong>g that aid beprovided on a “fair, just, <strong>and</strong> equitable basis.”Wash<strong>in</strong>gton v. Board <strong>of</strong> Supervisors <strong>of</strong> San Diego Cy. (California). 19A state cour<strong>the</strong>ld that <strong>the</strong> county could not impose an eligibility condition not permitted by state law (a threemonth time limit for able-bodied adults) based on a claim <strong>of</strong> f<strong>in</strong>ancial impossibility.Lampk<strong>in</strong> v. Lum (California). 20A state court <strong>in</strong>validated as contrary to state law acounty GA policy that limited aid to employables to n<strong>in</strong>e out <strong>of</strong> twelve months.L.T. v. New Jersey Dept <strong>of</strong> Human Services (New Jersey). 21 A state court <strong>in</strong>validated ascontrary to state law a regulation sett<strong>in</strong>g a twelve month time limit on temporary rentalassistance, a program to prevent homelessness.C. Apply<strong>in</strong>g Protections <strong>in</strong> O<strong>the</strong>r Non-Income Support Statutes to <strong>Welfare</strong> Participants1. Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) <strong>and</strong> §504 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rehabilitation ActWhy should welfare program applicants <strong>and</strong> participants look to <strong>the</strong> federal ADA <strong>and</strong>/orRehabilitation Act for protection? <strong>Welfare</strong> program requirements, especially work programrequirements, may place extra burdens <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals with disabilities or may exclude <strong>the</strong>m fromparticipation <strong>in</strong> programs from which <strong>the</strong>y could benefit. <strong>The</strong>se burdens may arise even thoughpolicies as written do not specifically discrim<strong>in</strong>ate aga<strong>in</strong>st those with disabilities. For example,<strong>in</strong>dividuals may be assigned to work activities that <strong>the</strong>y cannot perform or <strong>the</strong>y may not be ableto comply with complicated adm<strong>in</strong>istrative procedures because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir disability.<strong>The</strong> Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA)/ Rehabilitation Act may provide a legalh<strong>and</strong>le to address <strong>the</strong>se problems s<strong>in</strong>ce it requires modifications that allow mean<strong>in</strong>gful access toMay 1999⋅ 9 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center<strong>the</strong> program. <strong>The</strong> application <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ADA to welfare programs, such as TANF, is largelyuntested, although some recent welfare cases have raised ADA claims.Overview <strong>of</strong> ADA<strong>The</strong> ADA is a federal civil rights statute that protects <strong>in</strong>dividuals with physical <strong>and</strong>mental disabilities aga<strong>in</strong>st discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> public <strong>and</strong> private activities, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> programs <strong>of</strong> state <strong>and</strong> local governments (Title II), employment (Title I), publicaccommodations <strong>and</strong> services by private entities (Title III), <strong>and</strong> telecommunications (Title IV). 22An earlier federal law, § 504 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rehabilitation Act <strong>of</strong> 1973 is generally similar to Title II <strong>and</strong>III <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ADA. (<strong>The</strong> Rehabilitation Act covers federal agencies <strong>and</strong> federally f<strong>in</strong>anced programs.)Lawsuits <strong>of</strong>ten <strong>in</strong>clude both ADA <strong>and</strong> Rehabilitation Act claims. 23Title II <strong>of</strong> ADA is relevant for TANF programs, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> federal TANF statute makesclear that <strong>the</strong> ADA <strong>and</strong> Rehabilitation Act apply to TANF programs. 24Key features <strong>of</strong> Title II <strong>of</strong> ADA. Title II provides that “no qualified <strong>in</strong>dividual with adisability shall, by reason <strong>of</strong> such disability, be excluded from participation <strong>in</strong> or be denied <strong>the</strong>benefits <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> services, programs or activities <strong>of</strong> a public entity, or be subjected to discrim<strong>in</strong>ationby any such entity.” 25 <strong>The</strong> ADA requires <strong>the</strong> covered entity (e.g. state <strong>and</strong> local governments <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> case <strong>of</strong> welfare programs) to make “reasonable accommodations” to assure mean<strong>in</strong>gful accessto programs <strong>and</strong> services. <strong>The</strong>re are extensive federal regulations <strong>and</strong> case law.To be protected under <strong>the</strong> ADA an <strong>in</strong>dividual must be a “qualified person with adisability.” This means <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual must meet <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> disability, which is broaderthan <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> disability for SSI <strong>and</strong> Title II disability purposes (<strong>the</strong>re is also an exclusionfor current illegal drug use). <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual must also meet <strong>the</strong> “essential eligibility requirements<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> program” with or without reasonable modifications. <strong>The</strong> question <strong>of</strong> what is an essentialeligibility requirement is a likely area <strong>of</strong> dispute.May 1999⋅ 10 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center<strong>The</strong> state or local governmental entity must make reasonable modifications <strong>in</strong> policies,practices or procedures when necessary to avoid discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on disability, unless <strong>the</strong>public entity can show that mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> modifications would alter fundamentally <strong>the</strong> nature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>service, program, or activity. What does this mean <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> welfare programs? This islikely to be an area <strong>of</strong> dispute.How can <strong>in</strong>dividuals raise ADA claims? Individuals can file adm<strong>in</strong>istrative compla<strong>in</strong>ts<strong>and</strong> can br<strong>in</strong>g court cases. <strong>The</strong>y can also raise <strong>the</strong> ADA <strong>in</strong> negotiations with <strong>the</strong> agency.May 1999⋅ 11 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law CenterIn what k<strong>in</strong>ds <strong>of</strong> welfare cases have ADA claims been raised?<strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g examples illustrate <strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> problems for which pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs have soughtrelief under <strong>the</strong> ADA. (In some cases <strong>the</strong>re may have been Rehabilitation Act claims as well.)Note that some cases do not rely exclusively on <strong>the</strong> ADA but raise o<strong>the</strong>r legal claims as well. Inaddition, <strong>in</strong> some cases <strong>the</strong> court did not reach a decision because <strong>the</strong> parties settled <strong>the</strong> case.Eligibility criteriaAFDC program rules: <strong>The</strong>re was litigation over <strong>the</strong> AFDC option to cover children upto age 19 if <strong>the</strong>y were expected to graduate from secondary school by age 19. Pla<strong>in</strong>tiffschallenged state decisions to deny AFDC to 18 year old high school students who were not likelyto graduate from high school before <strong>the</strong>ir 19 th birthdays because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir disabilities. ADAchallenges <strong>in</strong> two cases resulted <strong>in</strong> one favorable decision <strong>and</strong> one unfavorable decision. InHoward v. Dept. <strong>of</strong> Social <strong>Welfare</strong>, 26 <strong>the</strong> Vermont court concluded that <strong>the</strong> requirement was notan essential eligibility requirement. It rejected arguments that federal law m<strong>and</strong>ated <strong>the</strong>requirement, f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> state could fund such benefits on its own, that <strong>the</strong>re was noevidence that HHS has refused to make reasonable accommodations by provid<strong>in</strong>g federalmatch<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>dividual cases to avoid discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on disability, <strong>and</strong> that <strong>the</strong> state couldnot discrim<strong>in</strong>ate aga<strong>in</strong>st those with disabilities to stay with<strong>in</strong> state appropriation limits. Itconcluded that extend<strong>in</strong>g pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs’ benefits until age 19 was a reasonable modification <strong>and</strong>m<strong>and</strong>ated by <strong>the</strong> ADA. In Aughe v. Shalala, 27 a federal court concluded that <strong>the</strong> requirement thata student complete high school by age 19 was an essential eligibility requirement <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> AFDCprogram <strong>and</strong> that <strong>the</strong> ADA <strong>and</strong> Rehabilitation Act did not require modification <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>requirement.General assistance (GA) rules: Time limits on GA benefits for disabled <strong>in</strong>dividualswere challenged <strong>in</strong> two states on ADA grounds with one favorable <strong>and</strong> one unfavorable decision.In Weaver v. New Mexico Human Services Dept., 28 <strong>the</strong> court concluded that impos<strong>in</strong>g a twelvemonth time limit on benefits for GA recipients with disabilities but not on GA benefits forMay 1999⋅ 12 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerchildren violated <strong>the</strong> ADA. In reach<strong>in</strong>g its decision <strong>the</strong> court concluded that <strong>the</strong> GA programwas a s<strong>in</strong>gle program <strong>and</strong> not two separate programs. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, <strong>in</strong> Doe v. Ch<strong>and</strong>ler, 29 afederal appeals court rejected claims that Hawaii’s one year time limit on GA for disabled<strong>in</strong>dividuals violated <strong>the</strong> ADA or equal protection. Although GA benefits for families were nottime-limited, <strong>the</strong> court said that <strong>the</strong> programs were separate <strong>and</strong> that equal benefits were notrequired.Benefit levelsAn AFDC waiver program approved by HHS <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> early 1990's <strong>in</strong>cluded an across-<strong>the</strong>boardCalifornia benefit AFDC level cut as “work <strong>in</strong>centive.” Litigation <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g various legalclaims was brought <strong>in</strong> Beno v. Shalala. 30 <strong>The</strong> lower court ruled unfavorably on <strong>the</strong> claim that <strong>the</strong>“work <strong>in</strong>centive” benefits as applied to those who were unable to work because <strong>of</strong> a disabilityviolated <strong>the</strong> ADA. <strong>The</strong> appellate court did not reach <strong>the</strong> ADA claim, but ruled <strong>in</strong>validated <strong>the</strong>waiver on procedural grounds, conclud<strong>in</strong>g that HHS’s approval process was deficient. Pla<strong>in</strong>tiffswere able to obta<strong>in</strong> exemptions from <strong>the</strong> benefit cut for those with disabilities <strong>in</strong> subsequentnegotiations with HHS over <strong>the</strong> renewed waiver <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> reach<strong>in</strong>g a subsequent court settlement.Adm<strong>in</strong>istrative practicesIn L<strong>in</strong>d v. Snider, 31 pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs challenged <strong>the</strong> agency’s implementation <strong>of</strong> GA cutbacks<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir failure to identify GA recipients who rema<strong>in</strong>ed eligible for GA based on disability. <strong>The</strong>claims were based on due process <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> ADA, <strong>and</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs challenged <strong>the</strong> failure to identifythose who were eligible, issue underst<strong>and</strong>able notices, <strong>and</strong> adm<strong>in</strong>ister <strong>the</strong> program <strong>in</strong> an orderlyway. <strong>The</strong> court granted temporary relief, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> parties later settled <strong>the</strong> case. <strong>The</strong> settlement<strong>in</strong>cluded provisions requir<strong>in</strong>g assistance to those need<strong>in</strong>g help to establish eligibility.Oregon Human <strong>Rights</strong> Coalition v. Concannon 32 challenged Oregon’s welfare verificationrequirements as unreasonably difficult for those with disabilities. <strong>The</strong> case raised ADA, dueprocess <strong>and</strong> federal <strong>and</strong> state law claims. <strong>The</strong> settlement <strong>in</strong>cluded provisions for better notices,greater worker assistance, staff tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> a grievance procedure.May 1999⋅ 13 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law CenterVarshavsky v. Perales 33 challenged New York’s elim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>of</strong> home fair hear<strong>in</strong>gs forthose with disabilities based on due process, ADA/Rehabilitation Act <strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r grounds. <strong>The</strong>court ruled for pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs.Henrietta D. v. Giuliani 34 challenged New York City’s failure to assist HIV <strong>and</strong> AIDSwelfare applicants <strong>in</strong> apply<strong>in</strong>g for various welfare benefits. Pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs argued that a city program,Division <strong>of</strong> AIDS Services, was <strong>in</strong>effectual <strong>in</strong> help<strong>in</strong>g pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs get access to <strong>the</strong> programs. Indeny<strong>in</strong>g prelim<strong>in</strong>ary relief, <strong>the</strong> court concluded that <strong>the</strong> program did help <strong>the</strong>m get access.Hunsaker v.County <strong>of</strong> Contra Costa. 35 This case challenged a California substance abusescreen<strong>in</strong>g test for GA applicants. <strong>The</strong> N<strong>in</strong>th Circuit Court <strong>of</strong> Appeals reversed a favorable lowercourt decision <strong>and</strong> ruled that <strong>the</strong> test did not deny pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs mean<strong>in</strong>gful access to <strong>the</strong> program.<strong>The</strong> parties reportedly later settled <strong>the</strong> case, with <strong>the</strong> county agree<strong>in</strong>g not to use <strong>the</strong> test.Work programsMitchell v. Barrios-Paoli 36 challenges New York City’s practice <strong>of</strong> assign<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividualswho are employable with limitations to workfare assignments that <strong>the</strong>y were unable to performbecause <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir disabilities. Pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs raised ADA, state law, <strong>and</strong> due process claims. <strong>The</strong> lowercourt barred assignments to workfare until adequate procedures (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g notices) were <strong>in</strong> place<strong>and</strong> barred sanctions for <strong>in</strong>dividuals who could not meet workfare requirements because <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>irlimitations. <strong>The</strong> appellate court found that <strong>the</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs raised serious questions about <strong>the</strong>fairness <strong>of</strong> workfare implementation but concluded that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs should challenge<strong>the</strong>ir assignments <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual actions, not <strong>in</strong> a class action. <strong>The</strong> court did require that notices to<strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>formation about how to challenge a workfare assignment <strong>and</strong> receivecont<strong>in</strong>ued benefits.Ramos v. McIntire 37 is a challenge to Massachusetts’ failure to provide mean<strong>in</strong>gful accessto state’s TANF Employment Service Programs for those with disabilities. Pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs soughtappropriate placements <strong>and</strong> services, screen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>terested TANF recipients for disabilities,<strong>and</strong> exemptions from <strong>the</strong> time limit until services are provided. <strong>The</strong> court denied classcertification <strong>and</strong> prelim<strong>in</strong>ary relief.May 1999⋅ 14 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law CenterMay 1999⋅ 15 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center2. Apply<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Protections <strong>in</strong> Employment Laws to Participants <strong>in</strong> <strong>Welfare</strong> WorkProgramsBackground 38Because <strong>the</strong> PRA greatly <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>the</strong> numbers <strong>of</strong> welfare recipients whom <strong>the</strong> states arerequired to have <strong>in</strong> work-related activities, <strong>in</strong>creased resort to legal <strong>the</strong>ories aris<strong>in</strong>g under lawsdesigned to protect workers are <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g importance. At <strong>the</strong> outset, organizers <strong>and</strong>advocates may wish to argue that workfare <strong>and</strong> comparable work obligations, as coerced labor, is<strong>in</strong>voluntary servitude <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>refore unconstitutional. Some commentators have supported thisview. 39 However, <strong>the</strong> requirement that recipients engage <strong>in</strong> work programs as a condition <strong>of</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ued receipt <strong>of</strong> benefits has been considered by courts that have addressed <strong>the</strong> question tobe a lawful exercise <strong>of</strong> governmental authority. 40However, once <strong>the</strong> state or county imposes work requirements on a welfare recipient, <strong>the</strong>recipient acquires many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> protections enjoyed by regular workers. Where <strong>the</strong> recipient hasacquired a regular job, <strong>the</strong>re is little question that <strong>the</strong> recipient acquires all <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> anyemployee. However, where <strong>the</strong> recipient is work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a workfare or community serviceposition, <strong>the</strong> state <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law is still <strong>in</strong> flux <strong>and</strong> court challenges may be necessary to securerights.<strong>The</strong> View <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Federal AgenciesTwo important policy statements from <strong>the</strong> federal government provide significantguidance by seek<strong>in</strong>g to extend common work place protections to public assistance recipientsengaged <strong>in</strong> workfare or community service. In May 1997, <strong>the</strong> U.S. Department <strong>of</strong> Labor(“DOL”) issued a guide to <strong>the</strong> states sett<strong>in</strong>g forth <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> workfare workers to protectionsunder federal employment laws <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g: <strong>the</strong> Fair Labor St<strong>and</strong>ards Act (“FLSA”), which governsMay 1999⋅ 16 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerm<strong>in</strong>imum wage <strong>and</strong> overtime rights; <strong>the</strong> Occupational Safety <strong>and</strong> Health Act (“OSH Act”), whichgoverns workplace health <strong>and</strong> safety; unemployment <strong>and</strong> anti-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation laws. <strong>The</strong> DOLGuide advises states to consider <strong>the</strong> applicability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se laws as <strong>the</strong>y design <strong>and</strong> implementwork programs. As <strong>the</strong> document states, it is a “start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t” <strong>and</strong> it “cannot provide <strong>the</strong>answers to <strong>the</strong> wide variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>in</strong>quiries that could be raised regard<strong>in</strong>g specific work programs.” 41In December 1997, <strong>the</strong> Equal Employment Opportunities Commission issued a notice(Number 915.002) to provide “guidance regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> application <strong>of</strong> anti-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation statutesto temporary” workers. <strong>The</strong> Notice clarifies that temporary workers are protected by antidiscrim<strong>in</strong>ationlaws <strong>and</strong> that, under many circumstances, workfare workers are consideredcovered workers. 42Secur<strong>in</strong>g Worker <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Courts</strong><strong>Courts</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> rights <strong>of</strong> workfare workers have extended many <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se workerprotections to workfare workers. By extension, <strong>the</strong>y would apply as well to welfare recipientswork<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> community service placements. <strong>The</strong> key question to address <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g whe<strong>the</strong>rwelfare recipients work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong>ir grants enjoy <strong>the</strong> same rights as o<strong>the</strong>r workers is whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>ywill be viewed as do<strong>in</strong>g work that is entitled to <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>in</strong> question. For example, <strong>in</strong>determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g whe<strong>the</strong>r a workfare worker is entitled to m<strong>in</strong>imum wage protection, a court wouldhave to determ<strong>in</strong>e whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> recipient is perform<strong>in</strong>g work that is covered by <strong>the</strong> Federal FairLabor St<strong>and</strong>ards Act. In many <strong>in</strong>stances, <strong>the</strong> answer to that question depends on whe<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong>worker can be considered an “employee”, <strong>the</strong> work is considered be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> “employ”, or <strong>the</strong>work is done for an “employer.” <strong>The</strong>se are very technical questions that will <strong>of</strong>ten only beresolved through litigation. In certa<strong>in</strong> situations, worker rights that <strong>the</strong> welfare recipients enjoysmay come from a state or local law. Examples are given below.May 1999⋅ 17 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center· Workers’ Compensation - Many states have <strong>in</strong>corporated workers’ compensationprotections directly <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir workfare statutes. In addition, several important court decisionshave held that workfare workers are covered by workers’ compensation protections. 43· Health <strong>and</strong> Safety Protections - Some states legislatively provide that workfareworkers are entitled to <strong>the</strong> exact same protections as regular workers. For example, New YorkState now provides that workfare workers must be provided <strong>the</strong> exact same coverage under <strong>the</strong>New York Public Employee Health <strong>and</strong> Safety Act as regular public employees. In o<strong>the</strong>rsituations, protections may be secured under <strong>the</strong> federal Occupational Health <strong>and</strong> Safety Act(OSHA). However, one should be aware OSHA protections do not extend to persons work<strong>in</strong>gfor public employers such as state, county, or local agencies. In most <strong>in</strong>stances where <strong>the</strong>re areextensive federal or state statutory health <strong>and</strong> safety protections, violations can only be pursuedby mak<strong>in</strong>g a compla<strong>in</strong>t to <strong>the</strong> agencies charged with enforcement.Resort to litigation may provide some relief to welfare recipients exposed to horrendouswork<strong>in</strong>g conditions <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r situations. Two court decisions <strong>in</strong> this area are <strong>in</strong>structive. InCapers v. Giuliani, a class <strong>of</strong> workfare workers assigned to street clean<strong>in</strong>g duties <strong>in</strong> New YorkCity challenged <strong>the</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> adequate work place health <strong>and</strong> safety protections under state welfarelaw provisions requir<strong>in</strong>g workfare placements to be made only to sites that comply with workerprotection requirements. <strong>The</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs claimed that <strong>the</strong>y were denied access to 1) toilets,wash<strong>in</strong>g facilities, <strong>and</strong> dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g water; 2) personal protective equipment; 3) traffic safetyequipment; <strong>and</strong> 4) tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> supervision. In August 1997, <strong>the</strong> Capers court certified a class<strong>and</strong> entered a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary <strong>in</strong>junction enjo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g assignment <strong>of</strong> any class member to a workfareassignment until <strong>the</strong> City provides necessary health <strong>and</strong> safety protections, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g access totoilets <strong>and</strong> potable water, gloves <strong>and</strong> face masks, <strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g regard<strong>in</strong>g potential worksitehazards. However, <strong>the</strong> order was vacated after <strong>the</strong> state passed legislation extended publicemployee workplace protections to workfare workers. 44In Ramos v. County <strong>of</strong> Madera, 45 <strong>the</strong> California Supreme Court held that AFDCrecipients, assigned to pick crops <strong>in</strong> exchange for <strong>the</strong>ir benefits, could challenge <strong>the</strong> violation <strong>of</strong>May 1999⋅ 18 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerstate statutes govern<strong>in</strong>g work<strong>in</strong>g conditions. For example, <strong>in</strong> Ramos “<strong>the</strong> compla<strong>in</strong>t alleges ... <strong>the</strong>field <strong>in</strong> which Manuela Ramos worked had no toilet or place to wash one’s h<strong>and</strong>s, contrary to[<strong>the</strong>] Health <strong>and</strong> Safety Code .... <strong>The</strong> water can allegedly had nei<strong>the</strong>r a cover ..., not a faucet, butra<strong>the</strong>r two or three beer cans used as common dr<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g cups ....” 46· M<strong>in</strong>imum Wage Protections - M<strong>in</strong>imum Wage Violations. This issue is likely tobe hotly litigated as more <strong>and</strong> more states rely on workfare to meet <strong>the</strong>ir participation rates <strong>and</strong>as <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> hours <strong>of</strong> participation <strong>in</strong> work activities m<strong>and</strong>ated by <strong>the</strong> PRA <strong>in</strong>creases from20 to 30 for s<strong>in</strong>gle parent households by <strong>the</strong> year 2000. For example, California has stated that itwill not apply m<strong>in</strong>imum wage protections to its welfare-to-work programs. <strong>Welfare</strong> recipientsperform<strong>in</strong>g work may be covered by <strong>the</strong> Federal Fair Labor St<strong>and</strong>ards Act (FLSA) <strong>and</strong>/or bystate m<strong>in</strong>imum wage protections. FLSA actions aga<strong>in</strong>st state-operated workfare programs maybe been h<strong>in</strong>dered by Sem<strong>in</strong>ole Tribe <strong>of</strong> Florida v. Florida, 47 where <strong>the</strong> U.S. Supreme Court held,<strong>in</strong> a 5-4 vote, that <strong>the</strong> immunity <strong>the</strong> Eleventh Amendment confers on states cannot be abrogatedby Congress when it is act<strong>in</strong>g through <strong>the</strong> Interstate Commerce Clause. Several courts havedismissed FLSA actions aga<strong>in</strong>st states s<strong>in</strong>ce Sem<strong>in</strong>ole Tribe based on a determ<strong>in</strong>ation that <strong>the</strong>recan be no cause <strong>of</strong> action <strong>in</strong> federal court because Congress lacked <strong>the</strong> power to abrogate states’Eleventh Amendment immunity <strong>in</strong> enact<strong>in</strong>g FLSA. 48This suggests that advocates should look tostate wage <strong>and</strong> hour law when consider<strong>in</strong>g challeng<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>imum wage violations <strong>in</strong> workfareprograms aga<strong>in</strong>st state actors. However, workfare programs with counties, municipalities, notfor-pr<strong>of</strong>its<strong>and</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r private employers may still be subject to FLSA coverage.Also at least one court, Johns v. Stewart, 49 has determ<strong>in</strong>ed that workfare workers are notemployees under FLSA. <strong>The</strong> Johns court determ<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>the</strong> relationship between <strong>the</strong>government <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> recipient under <strong>the</strong> welfare program precluded recipients from be<strong>in</strong>gemployees when <strong>the</strong>y work <strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong>ir cash grant. This decision is not consistent with <strong>the</strong> UnitedStates Department <strong>of</strong> Labor’s recent guidance <strong>in</strong>dicates that workfare workers are, <strong>in</strong> most<strong>in</strong>stances, employees with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> FLSA def<strong>in</strong>ition.May 1999⋅ 19 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center<strong>The</strong> authors are aware <strong>of</strong> only one post-PRA case challeng<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> calculation <strong>of</strong> workfarehours based on less than <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum wage. In that case, Cordos v. Turner, 50 which wasbrought by <strong>the</strong> <strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center along with <strong>the</strong> National Employment Law Project <strong>and</strong> whichhas been settled, 51 <strong>the</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>tiff worked for less than <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum wage <strong>in</strong> New York City’sworkfare program clean<strong>in</strong>g sanitation garages. In ano<strong>the</strong>r case <strong>in</strong> Ohio, pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs persuaded <strong>the</strong>local county to calculate <strong>the</strong> hours <strong>of</strong> work based on <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum wage by threaten<strong>in</strong>g to filelitigation.· Prevail<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> Liv<strong>in</strong>g Wage Violations. Workfare workers may also be entitled tohave <strong>the</strong>ir work hours calculated us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> “prevail<strong>in</strong>g wage” or “liv<strong>in</strong>g wage” <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> locality <strong>in</strong>which <strong>the</strong>y work. Some municipalities, counties, states, or public authorities (such as schoolboards) have enacted prevail<strong>in</strong>g or liv<strong>in</strong>g wage statutes.In Brukhman v. Giuliani 52 a New York court entered a class-wide prelim<strong>in</strong>ary <strong>in</strong>junctionrequir<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> City defendants to calculate <strong>the</strong> hours to be worked by all workfare workers us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> prevail<strong>in</strong>g rate <strong>of</strong> wage for regular workers perform<strong>in</strong>g similar or comparable work. <strong>The</strong> Cour<strong>the</strong>ld that us<strong>in</strong>g only <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum wage to calculate workfare hours violated state constitutional<strong>and</strong> statutory prevail<strong>in</strong>g wage protections. Pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs also alleged that <strong>the</strong> challenged practicedeprived <strong>the</strong>m <strong>of</strong> due process <strong>and</strong> equal protection under law, constituted an unconstitutionaltak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir property (<strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> labor) without just compensation, <strong>and</strong> unjustly enriched<strong>the</strong> City defendants. That decision was reversed when <strong>the</strong> state legislature enacted a statutorychange bas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> calculation <strong>of</strong> workfare hours on <strong>the</strong> m<strong>in</strong>imum wage ra<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> prevail<strong>in</strong>g wage.However, campaigns geared to ty<strong>in</strong>g workfare hours to prevail<strong>in</strong>g or liv<strong>in</strong>g wages are animportant way to highlight <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>equities <strong>of</strong> workfare programs <strong>and</strong> to generate <strong>in</strong>terest fromorganized labor.· Unemployment Compensation. Unemployment compensation is generally notavailable for recipients participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> work relief. <strong>The</strong> Federal Unemployment Tax Act permitsstates to exclude “work relief” participants from unemployment <strong>in</strong>surance coverage, 53 <strong>and</strong> moststates have taken that option. However, recipients may acquire eligibility if <strong>the</strong>y perform workMay 1999⋅ 20 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerfor a private employer under circumstances where <strong>the</strong> placement could be said to fall outside <strong>the</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>of</strong> “work relief.” <strong>The</strong>re is no case history <strong>in</strong> this area upon which to rely <strong>and</strong> anylitigation that is brought will be a very fact-specific <strong>and</strong> novel test case.· Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation. <strong>Welfare</strong> recipients assigned to workfare or community services workare likely covered by a number <strong>of</strong> federal, state, <strong>and</strong> local statutes designed to protect aga<strong>in</strong>stdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ation or harassment based on gender, race, national orig<strong>in</strong>, age, disability, or o<strong>the</strong>rfactors. <strong>The</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> protections will vary from state to state <strong>and</strong> city to city. To secure<strong>the</strong> protections <strong>of</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> statutes, an aggrieved person may first have to compla<strong>in</strong> to <strong>the</strong>adm<strong>in</strong>istrative agency prior to commenc<strong>in</strong>g litigation.· Displacement <strong>of</strong> Paid Workers. <strong>The</strong> federal TANF statute provides limitedprotections aga<strong>in</strong>st displacement. It proscribes fill<strong>in</strong>g vacancies where an employee is on lay<strong>of</strong>ffrom <strong>the</strong> same or substantially equivalent job or where <strong>the</strong> employer has term<strong>in</strong>ated a worker or<strong>in</strong>voluntarily reduced its workforce <strong>in</strong> order to take workfare workers. 54 Displacement claims,however, may exist under both collective barga<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g agreements as well as state <strong>and</strong>/or local laws.In Melish et al. v. City <strong>of</strong> New York, 55 two unions represent<strong>in</strong>g municipal workers claimthat New York City is violat<strong>in</strong>g state law, which prohibits workfare assignments that displaceregular workers. Pla<strong>in</strong>tiffs claim that workfare assignments <strong>in</strong>clude pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> carpentry at <strong>the</strong>Parks Department, work previously done exclusively by unionized workers. <strong>The</strong> compla<strong>in</strong>talleges that from 1988 to 1996 <strong>the</strong> number <strong>of</strong> unionized pa<strong>in</strong>ters decreased from 30 to 5 <strong>and</strong>carpenters from 54 to 22 <strong>and</strong> that <strong>the</strong> City has refused to fill vacancies <strong>and</strong> is <strong>in</strong>stead us<strong>in</strong>gworkfare workers to do <strong>the</strong> same work. It is unclear whe<strong>the</strong>r a comparable displacement claimcould be brought by <strong>the</strong> workfare workers.3. Apply<strong>in</strong>g O<strong>the</strong>r Civil <strong>Rights</strong> LawsImplementation <strong>of</strong> TANF has particularly harmed m<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>se harms may beexacerbated by adm<strong>in</strong>istrative practices that disproportionately affect particular groups, such asMay 1999⋅ 21 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerthose who are non-English speak<strong>in</strong>g, persons <strong>of</strong> color, <strong>and</strong> those with disabilities. For example, arecent study found disparate treatment <strong>of</strong> African-American <strong>and</strong> white women <strong>in</strong> award<strong>in</strong>gdiscretionary transportation allowances under Virg<strong>in</strong>ia’s welfare work program. It also foundthat m<strong>in</strong>ority women received less favorable treatment from employers, such as less desirablework hours. 56And a recent Associated Press report noted <strong>the</strong> shift<strong>in</strong>g racial composition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>welfare rolls s<strong>in</strong>ce 1994 with African-Americans, Hispanics, <strong>and</strong>/or Native Americans nowrepresent<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g proportion <strong>of</strong> welfare recipients <strong>in</strong> over half <strong>the</strong> states. 57 Federal,state, <strong>and</strong> local Civil <strong>Rights</strong> laws are an important tool to assure fairer treatment for <strong>the</strong>se groups.<strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g identifies civil rights protections, but is not an exhaustive review <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>law. For each law, <strong>the</strong>re is also a body <strong>of</strong> court decisions outside <strong>the</strong> welfare context which willbe relevant to determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> applicability <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law to welfare programs. Generally, courtshave not yet been asked to apply <strong>the</strong>se civil rights protections <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> welfare context.In exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> potential applicability <strong>of</strong> any law, advocates must consider, for example,<strong>the</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong>fered by each statute, which <strong>in</strong>dividuals can claim <strong>the</strong> protection <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> law, what entities are subject to <strong>the</strong> law’s prohibitions on discrim<strong>in</strong>ation, <strong>and</strong> what remedies<strong>the</strong> law provides. <strong>The</strong>re are also important questions to consider <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g how to enforcerights. For example, <strong>in</strong>dividuals may have to choose between seek<strong>in</strong>g enforcement from anadm<strong>in</strong>istrative agency or <strong>the</strong> courts , <strong>and</strong> where such options exist, will have to make strategicchoices. In some situations, <strong>in</strong>dividuals will have to file a compla<strong>in</strong>t with an adm<strong>in</strong>istrativeagency before <strong>the</strong>y can go to court. Advocates will want to consider us<strong>in</strong>g civil rights protectionsnot only affirmatively to seek changes <strong>in</strong> discrim<strong>in</strong>atory policies <strong>and</strong> practices, but alsodefensively where an <strong>in</strong>dividual is threatened with a sanction <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> event giv<strong>in</strong>g rise to <strong>the</strong>sanction <strong>in</strong>volved discrim<strong>in</strong>ation.Federal Civil <strong>Rights</strong> LawsMay 1999⋅ 22 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center<strong>The</strong> PRA specifically provides that TANF programs are subject to Title VI <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Civil<strong>Rights</strong>, <strong>the</strong> Age Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation Act <strong>of</strong> 1975, <strong>the</strong> Americans With Disabilities Act, <strong>and</strong> Section504 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Rehabilitation Act. 58 <strong>The</strong> Balanced Budget Act which appropriated funds for <strong>Welfare</strong>-To-Work <strong>in</strong>itiatives also provides that <strong>the</strong> anti-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation laws cited <strong>in</strong> TANF also apply towelfare-to-work programs. 59In addition, <strong>the</strong> Cl<strong>in</strong>ton Adm<strong>in</strong>istration has taken <strong>the</strong> position that<strong>the</strong> range <strong>of</strong> civil rights laws apply to welfare programs. 60 As <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fall <strong>of</strong> 1998 various federalagencies were <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> draft<strong>in</strong>g guidance on how federal civil rights laws apply to welfareprograms. 61<strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g protections apply (see above for discussion <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> ADA <strong>and</strong>Rehabilitation Act) :· Title VI <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Civil <strong>Rights</strong> Act. This law generally prohibits direct or <strong>in</strong>directdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ation aga<strong>in</strong>st an <strong>in</strong>dividual based on race, color, or national orig<strong>in</strong> by any program oractivity receiv<strong>in</strong>g federal assistance. Thus, state, local <strong>and</strong> private agencies which directlyreceive TANF fund<strong>in</strong>g should be covered. In addition, programs which receive <strong>the</strong> benefit <strong>of</strong>work performed by TANF recipients should arguably be covered. Covered programs cannotdiscrim<strong>in</strong>ate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> provision <strong>of</strong> applications, benefits, work assignments, or any o<strong>the</strong>r servicesunless <strong>the</strong> program can advance a substantial <strong>and</strong> legitimate justification for such differentialtreatment. Even if <strong>the</strong>re is a justification, <strong>the</strong> practice cannot cont<strong>in</strong>ue if <strong>the</strong>re is an similareffective alternative that reduces <strong>the</strong> discrim<strong>in</strong>ation.<strong>The</strong>re have been some attempts to use Title VI In <strong>the</strong> welfare context:Secur<strong>in</strong>g multil<strong>in</strong>gual procedures. Court cases <strong>and</strong> cases brought before <strong>the</strong> U.S.Department <strong>of</strong> Health <strong>and</strong> Human Services have succeeded <strong>in</strong> requir<strong>in</strong>g that agencies have AFDCprocedures to meet <strong>the</strong> needs <strong>of</strong> non-English speak<strong>in</strong>g or limited-English pr<strong>of</strong>icient applicants<strong>and</strong> recipients. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>in</strong>clude requirements for bil<strong>in</strong>gual notices <strong>and</strong> forms, multil<strong>in</strong>gualpersonnel, staff tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, notices <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> multil<strong>in</strong>gual services, <strong>and</strong> procedures tomonitor compliance. This advocacy was built on U.S. Supreme Court decisions recogniz<strong>in</strong>g thatMay 1999⋅ 23 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerfailure to provide multil<strong>in</strong>gual services may constitute discrim<strong>in</strong>ation on <strong>the</strong> basis <strong>of</strong> nationalorig<strong>in</strong>. 62 Us<strong>in</strong>g Title VI to attack restrictive eligibility rules. A pend<strong>in</strong>g case before HHS’Office <strong>of</strong> Civil <strong>Rights</strong> 63 challenges New Jersey’s policy <strong>of</strong> deny<strong>in</strong>g a benefit <strong>in</strong>crease for a childborn to a person receiv<strong>in</strong>g AFDC (also known as a “family cap”). In January 1995, <strong>the</strong> OCRissued a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that no <strong>in</strong>tentional discrim<strong>in</strong>ation had occurred, but it reservedjudgment as to <strong>the</strong> claim that <strong>the</strong> policy has a disparate effect on racial <strong>and</strong> ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities untilit received data follow<strong>in</strong>g implementation <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> policy. <strong>The</strong> case arose <strong>in</strong> conjunction with anattempt to overturn a waiver granted to New Jersey for this policy by <strong>the</strong> Secretary <strong>of</strong> HHS. InC.K. v. Shalala, 64 <strong>the</strong> federal appellate court rejected all <strong>of</strong> pla<strong>in</strong>tiff’s claims, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g statutory<strong>and</strong> constitutional claims. A state court challenge rais<strong>in</strong>g state constitutional claims wassubsequently filed. It is pend<strong>in</strong>g.· Employment Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation Laws.Title VII <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Civil <strong>Rights</strong> Act <strong>of</strong> 1964 protects <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> job tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, jobplacement <strong>and</strong> work environments from discrim<strong>in</strong>ation by employers <strong>and</strong> employment agencieswith 15 or more employees based on race, color, religion, national orig<strong>in</strong> or sex. This protectionextends to sexual <strong>and</strong> racial harassment, discrim<strong>in</strong>ation which affects m<strong>in</strong>orities or women<strong>in</strong>tentionally or un<strong>in</strong>tentionally, <strong>and</strong> discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on pregnancy. As discussed above, akey question that will arise is whe<strong>the</strong>r welfare work program participants will be covered under<strong>the</strong> law, <strong>and</strong> accord<strong>in</strong>g to experts, many courts have construed Title VII liberally to cover<strong>in</strong>dividuals who are not <strong>in</strong> a traditional employment relation. 65In <strong>the</strong> Spr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>of</strong> 1998, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Welfare</strong> Law Center <strong>and</strong> NOW Legal Defense <strong>and</strong> EducationFund filed a compla<strong>in</strong>t with <strong>the</strong> Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on behalf <strong>of</strong> aworkfare worker who was sexually harassed at her TANF-assigned work site. <strong>The</strong> ongo<strong>in</strong>gharassment was so severe, <strong>the</strong> worker left her workfare assignment. <strong>The</strong> EEOC has yet to reacha determ<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> case.May 1999⋅ 24 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law CenterO<strong>the</strong>r statutes. <strong>The</strong> Age Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> Employment Act <strong>of</strong> 1967 protects those 40or older from discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on age by employers (with 20 or more employees) <strong>and</strong> state<strong>and</strong> local governments. <strong>The</strong> Equal Pay Act <strong>of</strong> 1963 requires equal pay for women <strong>and</strong> men dosubstantially similar work, unless factors o<strong>the</strong>r than sex justify <strong>the</strong> differences, e.g. senioritysystem.· Age Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation Act <strong>of</strong> 1975 bars discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on age <strong>in</strong> federally-fundedprograms or activities.· Title IX <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Education Amendments <strong>of</strong> 1972 bars discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on sex <strong>in</strong>federally-funded education programs or activities. This will be an important h<strong>and</strong>le for thosewho suffer gender-based discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> welfare tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs, for example, programs thatdo not take women because <strong>the</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is for stereotypically male jobs.State <strong>and</strong> Local Laws Aga<strong>in</strong>st Discrim<strong>in</strong>ationState <strong>and</strong> local laws may <strong>of</strong>fer protection aga<strong>in</strong>st additional forms <strong>of</strong> discrim<strong>in</strong>ation, forexample, discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on sexual orientation. In addition, <strong>the</strong> agencies charged wi<strong>the</strong>nforc<strong>in</strong>g such protections may be favorable forums for advocacy.D. <strong>Role</strong> <strong>of</strong> Federal Constitution<strong>The</strong> United States Constitution is <strong>the</strong> highest law <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> United States. No law,regulation, policy or practice is legal if it violates <strong>the</strong> Constitution.<strong>The</strong> Constitution secures many fundamental rights, such as free speech, freedom <strong>of</strong>religion, <strong>and</strong> freedom from unreasonable searches.It also provides for “equal protection <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> laws” <strong>and</strong> “due process <strong>of</strong> law.” <strong>The</strong>se twopr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong> particular have played an important role <strong>in</strong> protect<strong>in</strong>g low <strong>in</strong>come people aga<strong>in</strong>st avariety <strong>of</strong> abuses <strong>in</strong> welfare programs. Many people have hoped that <strong>the</strong>y would also provideMay 1999⋅ 25 ⋅

<strong>Welfare</strong> Law Centerfor a “right to life” or “right to m<strong>in</strong>imum subsistence benefits,” but as we discuss later <strong>in</strong> thispaper, those hopes were dashed long ago. But we turn now to <strong>the</strong> equal protection clause, where<strong>the</strong>re have been some successes, notably <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>validat<strong>in</strong>g welfare laws deny<strong>in</strong>g benefits to newstate residents, <strong>and</strong> discrim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st unemployed mo<strong>the</strong>rs, non-citizens, <strong>and</strong> families <strong>in</strong>which <strong>the</strong> parents were unmarried. <strong>The</strong>re also have been disappo<strong>in</strong>tments.It is important to note that state courts also have <strong>the</strong> power to <strong>in</strong>terpret <strong>the</strong> federalconstitution <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong>re have been some victories. In addition, state courts can <strong>in</strong>terpret <strong>the</strong>ir ownstate constitutional which generally have provisions on equal protection <strong>and</strong> due process, <strong>and</strong>some state courts will provide protections under state constitutions that go beyond <strong>the</strong> federalconstitutional protections. 66May 1999⋅ 26 ⋅