Mud Creek Watershed Restoration Plan - Henderson County Center

Mud Creek Watershed Restoration Plan - Henderson County Center

Mud Creek Watershed Restoration Plan - Henderson County Center

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

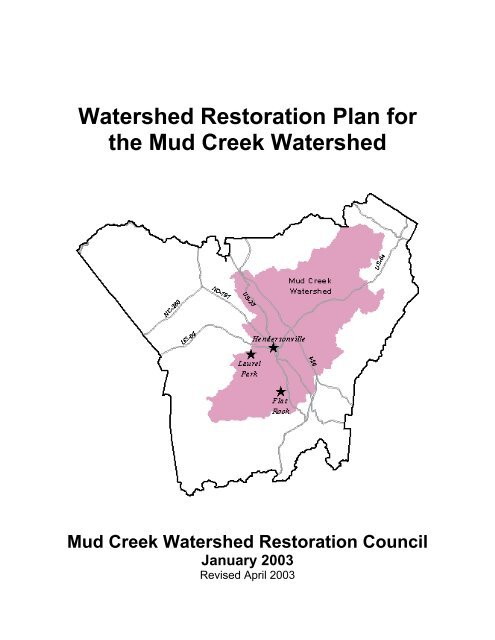

<strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> forthe <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong><strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> CouncilJanuary 2003Revised April 2003

TABLE OF CONTENTSTable of Contents ........................................................................................................................... iList of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iiList of Figures................................................................................................................................ iiExecutive Summary..................................................................................................................... ivSection 1: Project Overview........................................................................................................ 11.1 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 11.2 The <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Council................................................................ 21.3 NC Division of Water Quality <strong>Watershed</strong> Assessment and <strong>Restoration</strong> Project................ 21.4 NC Wetlands <strong>Restoration</strong> Program Local <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ning ......................................... 31.5 Tennessee Valley Authority Integrated Pollutant Source Identification ............................ 3Section 2: <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization ................................................................ 42.1 Introduction......................................................................................................................... 42.2 Hydrology and Sub-<strong>Watershed</strong> Delineation ....................................................................... 42.3 Soils..................................................................................................................................... 62.4 Land Use/Land Cover in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>.......................................................... 62.5 Water Quality and Stream Health....................................................................................... 92.5.1 General Conclusions of WARP Assessment.................................................................... 92.5.2 DWQ Use Support Ratings ........................................................................................... 102.5.3 DWQ’s <strong>Watershed</strong> Assessment and <strong>Restoration</strong> Project (WARP) ............................... 122.5.4 Volunteer Water Information Network ......................................................................... 152.5.5 Channel and Riparian Buffer Condition....................................................................... 162.6 Local Water Quality Initiatives......................................................................................... 192.6.1 Local Environmental Ordinances................................................................................. 192.6.2 Land Use <strong>Plan</strong>ning and Zoning .................................................................................... 202.6.3 State Stormwater Regulations....................................................................................... 212.6.4 Environmental and Conservation Organization (ECO) ............................................... 212.6.5 Volunteer Water Information Network ......................................................................... 222.6.6 Southside Development Initiative ................................................................................. 222.6.7 Apple Country Greenwy Commission........................................................................... 232.6.8 Carolina Mountain Land Conservancy ........................................................................ 232.6.9 French Broad <strong>Watershed</strong> Training <strong>Center</strong>................................................................... 24Section 3: Recommendations .................................................................................................... 253.1 Stormwater........................................................................................................................ 263.1.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................... 263.1.2 Strategies to minimize impacts of stormwater runoff from future development ........... 303.1.3 Strategies to reduce impacts of stormwater runoff from existing development............ 323.2 Agricultural Non Point Source Pollution.......................................................................... 353.2.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................... 35Table of ContentsPage i

3.2.2 Strategies to Control Agricultural Nonpoint Source Pollution .................................... 373.3 Habitat Degradation.......................................................................................................... 403.3.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................... 403.3.2 Strategies to Address Habitat Degradation.................................................................. 413.4 Upland Sources of Sedimentation..................................................................................... 443.4.1 Overview ....................................................................................................................... 443.4.2 Strategies to Address Upland Sources of Sedimentation.............................................. 46Section 4: Next Steps.................................................................................................................. 494.1 Present <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> to the Community................................................... 494.2 Formalize <strong>Watershed</strong> Council........................................................................................... 494.3 Hire <strong>Watershed</strong> Coordinator............................................................................................. 494.4 Prioritize Recommendations............................................................................................. 494.5 Set Measurable <strong>Watershed</strong> Improvement Goals............................................................... 494.6 Secure Grants to Implement Projects................................................................................ 50References.................................................................................................................................... 51Appendix A.................................................................................................................................. 52Appendix B .................................................................................................................................. 53LIST OF TABLESTable 2.1: Summary of area, stream miles and slope by subwatershed. ....................................... 5Table 2.2. Percentage of subwatershed area by land use/cover..................................................... 7Table 2.3: Channelization and Buffers in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed.......................................... 18Table 2.4: Summary of Zoning in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed...................................................... 21Table 3.1: Existing Stormwater Management Ordinances in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed............ 29Table 3.2: Estimated sediment loading rates in tons/acre for land uses in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed. ................................................................................................................... 45LIST OF FIGURESFigure 1.1: Map of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>. ............................................................................ 1Figure 2.1: Streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>........................................................................ 4Figure 2.2: Subwatersheds in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>............................................................. 5Figure 2.3: Generalized Land Use/Land Cover Patterns in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>............... 8Figure 2.4: Use Classifications for streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> ................................. 10Figure 2.5: Use-support Ratings for streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> ............................... 11Figure 2.6: WARP Biological Monitoring Sites......................................................................... 12Figure 2.7: Apple orchards and benthic macroinvertebrate communities inthe Clear <strong>Creek</strong> and Devils Fork Subwatersheds..................................................... 13Figure 2.8: Location of WARP water chemistry sampling sites. ............................................... 14Table of ContentsPage ii

Figure 2.9: VWIN monitoring sites in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>............................................. 15Figure 2.10: Map of <strong>Henderson</strong>ville showing <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> prior to channelization...................... 17Figure 3.1: Stream vulnerability rating based on percent impervious cover in the<strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> – by subwatershed................................................................ 27Figure 3.2: Existing wetlands and areas with hydric soils in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>........... 28Figure 3.3: Flooding at <strong>Henderson</strong>ville’s Southside, just one of many areas of chronic floodingexacerbated by floodplain development and impervious cover............................... 29Figure 3.4: Agricultural land uses in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>. .............................................. 35Figure 3.5: Cattle with direct access to <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>.................................................................... 36Figure 3.6: Cattle access points to streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>.................................. 36Figure 3.7: Eroding streambanks cause sediment to fill stream channels impacting aquatichabitat....................................................................................................................... 40Figure 3.8: Site of Clear <strong>Creek</strong> stream restoration project ......................................................... 42Figure 3.9: Runoff from gravel driveway in the upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed........................... 44Figure 3.10: Estimated annual sediment load from land uses in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed ....... 45Figure 3.11: Number of building permits issued for new residential units in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>1996-2002 ................................................................................................................ 46Table of ContentsPage iii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYFor the past three years, local stakeholders and state and federal resource managers have workedtogether to gather data and outline a plan to restore the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. This documentrepresents the culmination of efforts undertaken by these partners to evaluate all possible sourcesand causes of water quality degradation and recommend a comprehensive set of strategies foraddressing these problems.Section 1 presents a brief overview of the project. In 2000, Land of Sky Regional Council ofGovernments convened local stakeholders in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed to develop a plan foraddressing water quality problems in the watershed. At that same time, the Division of WaterQuality initiated an independent study to identify causes and sources of impairment in the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> and two of its tributaries, Bat Fork and Clear <strong>Creek</strong>. These streams are on the NorthCarolina 303(d) List of Impaired Waterbodies. Concurrently, the NC Wetlands <strong>Restoration</strong>Program was interested in identifying potential stream and wetland restoration projects in the<strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed and agreed to collect additional stream and watershed data through apartnership with the Tennessee Valley Authority to supplement efforts already underway in thewatershed.Section 2 summarizes current conditions in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed including land use,water quality, channel and buffer conditions, habitat and wetlands. The <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershedis 113 mi 2 comprising approximately one-third of <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>’s land area. There arethree municipalities in the watershed: <strong>Henderson</strong>ville, Flat Rock and Laurel Park. Forty-fivepercent of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed is forested, 25 percent is residential, commercial orindustrial, and 23 percent is agricultural. The <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed has roughly 10%impervious cover, however, the percent of imperviousness varies greatly throughout thewatershed with some areas far exceeding the 10% threshold where declines in water quality andaquatic communities are noted. Without appropriate water quality protection measures,increasing urbanization in the watershed will further exacerbate existing water quality problems.The Volunteer Water Information Network rates many streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed asbelow average and poor due to nutrient enrichment, turbidity and high metals concentrations. Acomprehensive watershed assessment conducted by the NC Division of Water Quality (DWQ) in2000-2002 indicates that biological communities in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed are impacted by anumber of factors including toxicants from agriculture and urban sources, scour from highstormflow volumes, poor in-stream habitat, and a lack of tributaries with healthy biologicalcommunities. In addition, DWQ monitoring showed that several streams violated the statestandards for fecal coliform bacteria levels.Historic practices such as channelizing streams, clearing streamside vegetation and draining andfilling wetlands for agriculture and suburban development are prevalent across the watershed.Because of these practices, the quality and distribution of adequate riparian buffers in the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> watershed are insufficient to protect water quality and promote good aquatic habitat. Inaddition, these practices exacerbate streambank erosion, increase sedimentation and increase thevolume and velocity of stormwater runoff.Pesticides from apple orchards and row crops likely degrade the biological communities ofstreams in the Clear <strong>Creek</strong> and Devils Fork area; both current and past use pesticides may play aExecutive SummaryPage iv

ole in stream degradation. Past use pesticides, such as DDT and chlordane, were widely used inagriculture and residential areas. In addition, row crop pesticides likely impact biologicalcommunities in upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>.Nutrient enrichment is evident in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed and possible nutrient sources includecattle waste, straight pipes, failing septic systems and runoff from lawns, gardens, golf coursesand crop land. In urban streams, the combined factors of toxicants such as metals, organicpollutants, and pesticides and scouring energy from high stormflow volumes severely limitbiological communities. Increasing turbidity levels noted in streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershedare probably the result of escalating land-disturbing activities.Section 3 outlines the management strategies recommended by the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong><strong>Restoration</strong> Council to address these problems. These recommendations are grouped into fourcategories and the specific recommendations are presented in Table ES.1:• Stormwater: Strategies to address the volume, velocity, and quality of post-constructionrunoff from existing and future roads and commercial and residential development.• Nonpoint Source Pollution from Agricultural Activities: Strategies to reduce pesticides,nutrients, sediment and bacteria and other agriculture related non-point source pollution.• Habitat Degradation: Strategies to improve aquatic habitat needed by aquatic organismsto survive and reproduce in a stream. The recommendations address the causes of habitatdegradation including sedimentation, bank erosion, channelization, lack of riparianvegetation, loss of riffles or pools, loss of woody habitat and streambed scour (i.e., flowthat washes away habitat).• Upland Sources of Sedimentation: Strategies to reduce sediment pollution fromconstruction activities and unpaved roads and driveways.Section 4 outlines the next steps for the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Council. Thesesteps include:• Present the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> to the community.• Restructure the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Council as a formal committee andseek appointments from the appropriate stakeholder groups.• Hire a <strong>Watershed</strong> Coordinator to work with stakeholders and agency partners toimplement the watershed plan.• Evaluate the management strategies and set long-term and short-term implementationpriorities.• Set measurable goals to track progress and document accomplishments.• Secure grants, as needed to implement education and restoration strategies.Executive SummaryPage v

Table ES.1: Proposed management strategies for addressing water quality and habitat concerns in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed.STORMWATERManagement Strategies• Develop and/or refine existing stormwater management ordinances and floodplaindevelopment ordinances.• Provide incentives to local residents to reduce stormwater runoff from existing and newdevelopment.• Review existing development ordinances and building codes for opportunities to minimizeimpervious surfaces.• Educate businesses and citizens about stormwater management issues and actions theycan take to reduce these impacts.• Consider establishing a stormwater utility to fund the stormwater program includingimprovements to the existing stormwater collection system.• Map existing stormwater collection systems to identify illicit connections and develop astrategy for redirecting these discharges to proper wastewater treatment facilities.• Implement a Stormwater BMP Retrofit Program to identify opportunities to reducestormwater impacts from existing development.• Promote pollution prevention and stormwater management by implementing BMPs ongovernment owned facilities including motor fleet maintenance areas, parks, and othersuitable sites.• Encourage local businesses to implement stormwater BMP retrofits by creating an awardprogram to cite local businesses’ accomplishmentsAG NON-POINT SOURCE POLLUTION• Promote innovative pest management practices to reduce the amount of pesticides appliedin the watershed and to reduce the likelihood for pesticides to enter streams.• Find research on pesticide drift management and work to develop new Ag Cost SharePractices to minimize pesticide drift.• Work with willing landowners to stabilize streams near orchards and row crops to minimizethe transport of historic pesticides.Lead Agency orOrganization 1 Funding 2Local GovernmentsLocal GovernmentsLocal GovernmentsLocal Governments,Council, CELocal GovernmentsNo costTax creditsNo costGrantsGrantsLocal Governments Local $$,GrantsLocal Governments,Council CELocal Governments,CouncilLocal Government,PEPS&WCD, CES&WCD, CES&WCDGrantsGrantsPrivatesectorACSPUnknownACSPExecutive Summary Page vi

Management StrategiesLead Agency orOrganization 1 Funding 2AG NON-POINT SOURCE POLLUTION continued….• Work with willing landowners to implement buffers and conventional conservation practicessuch as cover crops, no till, field borders, filter strips, on row crop land.• Initiate groundwater monitoring to determine if historic pesticides are moving from the soilsof ag fields to streams through the groundwater.• Work with willing landowners to implement animal waste practices such as livestockexclusion, feed/waste structures, stream crossing and buffer strips to protect water quality.HABITAT DEGRADATION• Restore 15,000 feet of the most critically eroding streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed toimprove habitat and water quality.S&WCDDWQS&WCDNCWRPACSPUnknownEQIP,ACSPNCWRP• Restore native vegetation along streams to stabilize streambanks and improve habitat. Local Governments Grants• Educate landowners about the importance of riparian buffers for streambank stabilization,water quality and habitat.• Evaluate the benefits of a buffer ordinance to protect lands adjacent to streams from futuredevelopment activities.Council, CELocal Governments• Permanently protect high priority wetlands and riparian buffers. Local Governments,CMLC, ACGCUPLAND SOURCES OF SEDIMENTATION• Consider the benefits of a local Sediment and Erosion Control Program to oversee localdevelopment activities.Local governmentsGrantsUnknownGrantsPermit Fees• Educate excavators and the public about how to control erosion. Local govts., CE Grants• Reduce the sediment pollution from unpaved roads, eroding road banks, and roadsideditches.Local governments,DOT, HOA1 Lead Agencies or Organizations are defined as follows: Council-<strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Council; Local Governments – <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>,<strong>Henderson</strong>ville, Flat Rock, and Laurel Park; PEP-Partners for Economic Progress; S&WCD-<strong>Henderson</strong> Soil and Water Conservation District; CE-<strong>Henderson</strong><strong>County</strong> Cooperative Extension; DWQ-Division of Water Quality; NCWRP-North Carolina Wetlands <strong>Restoration</strong> Program; CMLC-Carolina Mountain LandConservancy; ACGC-Apple Country Greenways Commission; DOT-North Carolina Department of Transportation; HOA-Home Owners Associations.2 ACSP-Agriculture Cost Share Program; EQIP-Environmental Quality Incentives Program; Grants – could include EPA 319 Nonpoint Source grants, NC CleanWater Management Trust Fund Grants; NCWRP-Wetland and Stream <strong>Restoration</strong> Funds; DOT-Regional road maintenance funds.DOTExecutive Summary Page vii

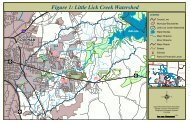

SECTION 1: PROJECT OVERVIEW1.1 Introduction<strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> is growing at arapid rate and much of this growthis occurring in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed (Figure 1.1). Across thewatershed, developers areconverting apple orchards andpasture lands and clearing forestedhillsides for residential andcommercial developments. Waterquality problems associated withgrowth and development, as wellas agricultural practices, areevident in many streams in the<strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>and two of its tributaries, Clear<strong>Creek</strong> and Bat Fork, are currentlyon the state’s 303(d) List ofImpaired Waterbodies. TheVolunteer Water InformationNetwork (VWIN) operated by theUniversity of North Carolina atAsheville rates many streams inthe <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed as belowaverage and poor. In addition tocurrent landscape changes anduses, historic practices such asdraining and filling wetlands,Figure 1.1: Map of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>.channelizing streams and clearing streamside vegetation further compromise the integrity ofthese natural systems and exacerbate the effects of growth and development on stream health andincrease the intensity and frequency of flooding.In late 1998, the Division of Water Quality (DWQ) awarded Land of Sky Regional Council ofGovernments (LOSRC) a grant to work with local stakeholders to develop a plan for addressingwater quality problems in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. In 1999, DWQ received a grant from theNC Clean Water Management Trust Fund (CWMTF) to identify causes and sources of streamimpairment through intensive monitoring and analysis and to develop watershed managementstrategies for eleven impaired watersheds across the state. The <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed wasselected as one of the eleven watersheds in the <strong>Watershed</strong> Assessment and <strong>Restoration</strong> Project(WARP). Concurrently, the NC Wetlands <strong>Restoration</strong> Program (NCWRP) was interested indeveloping a local watershed plan for the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed in order to identify potentialrestoration projects that the NC Department of Transportation (DOT) can implement to fulfillfuture compensatory mitigation requirements. NCWRP agreed to collect additional stream andwatershed data to supplement WARP and LOSRC efforts already underway in the watershedthrough a partnership with the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).Section 1: Project Overview Page 1FlatRock

Bat Fork. The overall goal of the project was to provide the foundation for future water qualityrestoration activities by: 1) identifying the most likely causes of biological impairment (such asdegraded habitat or specific pollutants); 2) identifying the major watershed activities and sourcesof pollution contributing to those causes (such as stormwater runoff from particular urban orrural areas, streambank erosion, or hydrologic modification); 3) outlining a watershed strategythat recommends restoration activities and best management practices (BMPs) to address theseproblems and improve the biological condition of the impaired streams.As part of this study, DWQ conducted extensive biological assessments in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed, sampled ambient and storm water quality and walked many miles of streams in thewatershed to assess stream habitat, morphology, and riparian zone condition. The study alsoevaluated watershed hydrologic conditions, land use, land management activities, and potentialpollution sources. WARP staff, located in Asheville, participated in <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> Councilmeetings and worked closely with local resource management professionals to draw on theconcerns and experience of watershed residents, local governments and others in evaluating thenature of water quality problems and outlining potential solutions. Once complete, theassessment report describing conclusions on these issues will be available to the CWMTF,watershed stakeholders, and other interested parties through the DWQ website. Preliminary datafrom this report are summarized in Section 2.1.4 NC Wetlands <strong>Restoration</strong> Program Local <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ningIn 2000, the NCWRP initiated a Local <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>ning program to conduct detailedrestoration planning in a limited number of Targeted Local <strong>Watershed</strong>s across the state. Theselocally-based plans include a comprehensive watershed assessment to identify causes andsources of nonpoint source impairment. The NCWRP will use these plans to identify wetlandand stream restoration projects to meet projected Department of Transportation compensatorymitigation requirements. Through this process, the NCWRP will work with local stakeholders toidentify and prioritize wetlands areas, stream reaches, riparian buffer areas and bestmanagement practices that will provide significant water quality improvement and otherenvironmental benefits to local watersheds. The NCWRP coordinates with local communitygroups, local governments, and others to develop and implement these plans. The NCWRPinitiated the local watershed planning process in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed to complement theefforts underway by the DWQ and <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Council.1.5 Tennessee Valley Authority Integrated Pollutant Source IdentificationIn 2000, the Tennessee Valley Authority developed a set of Integrated Pollutant SourceIdentification (IPSI) tools to help DWQ, the NCWRP and the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> Councilidentify and prioritize water quality improvement and protection measures in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed. The IPSI consists of a geographical database of watershed features such as landcover, estimates of impervious land cover, streams, soils, slope, and information about potentialnonpoint sources of pollution including streambank erosion sites, livestock operations, andunpaved roads. The TVA IPSI data and methods are summarized in the report <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong><strong>Watershed</strong> Nonpoint Source Pollution Inventory and Pollutant Load Estimates (TVA,2001). A subset of the TVA IPSI data are summarized in Section 2. The complete reportsummarizing the IPSI data for the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed is available athttp://h2o.enr.state.nc.us/wrp/pdf/lwp/mud_creek_lwp_ipsi.pdf.Section 1: Project Overview Page 3

SECTION 2: MUD CREEK WATERSHED CHARACTERIZATION2.1 IntroductionThis section summarizes current watershed conditions in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed includingland use, water quality, channel and buffer conditions, habitat and wetlands. The objective ofthis analysis is to characterize existing watershed conditions and identify existing and potentialsources of water quality degradation. The Tennessee Valley Authority’s (TVA) IntegratedPollutant Source Identification (IPSI) for the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed served as an importantsource of data on land use/cover, imperviousness, and stream channel and riparian conditions.The IPSI is a geographic database and pollutant loading model based on interpretation of lowaltitudecolor infrared aerial photographs taken in March 2001 (TVA, 2001). In addition, theCouncil also relied heavily on water quality and habitat assessment data gathered by WARP andwater quality monitoring data collected by VWIN.2.2 Hydrology and Sub-<strong>Watershed</strong> DelineationThe <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershedis 113 mi 2 , comprisingapproximately one-thirdof <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>’sland area. <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>begins in southwest<strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> andflows east and norththrough <strong>Henderson</strong>villeto the French Broad River(Figure 2.1). Thewatershed is bounded tothe east and south by theTennessee Valley Divide,to the north by a steepmountain range and to thewest by a lower divide.<strong>Henderson</strong>ville receivesan average of 56 inches ofrainfall annually. WesternNorth Carolina has beenin a drought since mid-1998, and rainfall at<strong>Henderson</strong>ville has been84%, 75%, and 76% ofthe annual average foryears 1999, 2000, and2001, respectively.Figure 2.1: Streams in the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 4

The size of the watershed and variability of stream types make it difficult to generalizewatershed conditions. To deal with these issues, the watershed was divided into fivesubwatersheds based upon topography, hydrology and land-use considerations. Thesubwatershed boundaries are shown on Figure 2.2.Table 2.1: Summary of area, stream miles and slope by subwatershed.Subwatershed Name Drainage area Stream Miles Average SlopeClear <strong>Creek</strong> 44.5 sq. miles 136 16%Bat Fork 8.6 sq. miles 57 6%Devils Fork 16.4 sq. miles 34 5%Upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> 20.5 sq. miles 61 17%Lower <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> 22.8 sq. miles 80 11%Total 112.8 sq. miles 368 14%Figure 2.2: Subwatershedsin the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong><strong>Watershed</strong>.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 5

2.3 SoilsThree general soil associations comprise the majority of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed soil types—(1) the Codurus-Toxaway-Rosman association, which are floodplain soils and consist of welldrained to very poorly drained soils that have loamy and sandy subsoils, (2) the Hayesville-Bradson association, which are soils on ridges and stream terraces and consist of gently slopingto moderately steep, well drained soils that have loamy and clayey subsoil, and (3) the Evard-Edneyville-Ashe association, which are soils occurring on mountain ridge tops and side slopesand consist of sloping to very steep, well drained and somewhat excessively drained soils thathave loamy subsoils (USDA, 1980).Hydric soils figure prominently in floodplain areas, especially in the Bat Fork, upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>,the southern part of lower <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>, and Devils Fork subwatersheds. Four percent of soils (4.1mi 2 ) in the watershed are hydric, and another seven percent (8.3 mi 2 ) have hydric inclusions.Many of these soils are actively drained for agriculture, and a small proportion has wetlandvegetation.2.4 Land Use/Land Cover in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>Land use patterns can have a profound effect on water quality and stream hydrology. To assessland use patterns in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed we evaluated land use and land cover datagenerated by TVA from aerial photographs taken in March 2001. TVA’s Integrated PollutantSource Identification (IPSI) determined that 45 percent of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed is forested,25 percent is residential, commercial or industrial, and 23 percent is agricultural. Although thepredominant land cover in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed is still forest cover, the watershed isexperiencing rapid growth and development due to increasing popularity as a retirementcommunity. On the whole, agriculture is declining in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>. There was a loss of25% of farmland between 1987 and 1997, and much of this land is being converted to residentialland. Agricultural commodities are changing, as well, with sod farms, and plasticulturevegetables replacing the traditional vegetable farms, orchards, corn, and dairies.Most of the forested land is along the northern and southern ridges that border the watershed,and, accordingly, the Clear <strong>Creek</strong> and upper and lower <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> subwatersheds have 39-60percent of their land use in forest. However, these areas are desirable for homesites, and newdevelopment is occurring in these steeper areas. The southern ridge of the Bat Forksubwatershed, for example, is a patchwork of homesites surrounding the Kenmure golf course.Agriculture is a significant portion of the watershed, accounting for more than a fifth of eachsubwatershed except those of upper and lower <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>. Apple orchards are prominent in thevalleys and on gentle slopes of the Clear <strong>Creek</strong> and Devils Fork subwatersheds and the Dunn<strong>Creek</strong> area of the Bat Fork subwatershed. Pasture, often for beef cattle, is sited along streamvalleys and accounts for at least nine percent of land use/cover in all subwatersheds. It isparticularly notable along the mainstems of Clear and <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>s, but also occurs along manytributaries. Row crops are usually in flat floodplain areas, and corn and market vegetables (e.g.,squash, beans, tomatoes, and peppers) are common.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 6

Figure 2.3: Generalized Land Use/Land Coverpatterns in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 8

2.5 Water Quality and Stream HealthThe primary goal of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Council is to improve and protectwater quality throughout the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. To accomplish this goal, the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>Council must understand the current condition of water quality and overall stream health in thewatershed, how these conditions have changed over time and what might be causing thesechanges. The following section describes existing water quality and habitat data for the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> watershed and provides some general conclusions about these data. The data used for thischaracterization include DWQ basinwide monitoring data, WARP <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> data and VWINmonitoring data. The purpose of this summary is to characterize water quality problems andstream health issues in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed based on these technical information sourcesand is not intended to provide detailed analysis of this information or to discuss sampling anddata methodologies.2.5.1 General Conclusions of WARP AssessmentWARP used the data summarized in the following sections to determine causes and sources ofbiological impairment for Bat Fork, Clear <strong>Creek</strong>, Devils Fork and <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>. Therecommendations listed in Section 3 of this document are designed in large part to address theproblems that the WARP study has illuminated. WARP concluded that a number of factorsimpact water quality and stream health in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed:• Pesticides: Based on the data available, pesticides are likely the primary factor causingtoxic impacts to benthic macroinvertebrate communities in apple growing areas(including Clear <strong>Creek</strong> and Devils Fork). Both current use pesticides used on apples androw crops and past use pesticides used on both agricultural and residential land may playa role in stream degradation. Toxic impacts were also noted in upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> andtomato/pepper pesticides were pinpointed as a most likely source of toxicity.• Habitat Degradation: Poor in-stream habitat for biological communities was awidespread problem in the watershed, but most notable in <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> and Bat Fork.Lack of woody riparian vegetation, extensive channelization, and sedimentation (fromboth in-stream and upland sources) are key factors responsible for habitat degradation.• Stormwater: In urban streams, the combined factors of toxicants (e.g., metals, organicpollutants, and pesticides) and scouring energy from high stormflow volumes severelylimit biological communities.• Nonpoint Source Pollution: Nutrient enrichment was a notable problem in Clear <strong>Creek</strong>and Devils Fork. Nutrient sources include cattle with stream access and possibly straightpipes and failing septic systems.• Cumulative Impacts: Combined impacts of toxicants from agriculture and urbansources, scour from high stormflow volumes, poor in-stream habitat, and a lack oftributaries with healthy biological communities are responsible for chronically impairedbiological communities in lower <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 9

WARP focused on 303(d) listed streams (Bat Fork, Clear <strong>Creek</strong>, and <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>). They did notintensively study many smaller streams in the watershed. However, the issues identified aboveare likely important for many streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed.2.5.2 DWQ Use Support RatingsIn 1997, DWQ assessed streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed as part of the basinwide planningprocess for the French Broad River Basin and determined that <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>, Bat Fork and Clear<strong>Creek</strong> do not support their use classifications for Class C waters. The use classifications forstreams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed are shown in Figure 2.4. Class C waters are protected forsecondary recreation, fishing, and aquatic life. Class C is the minimum protection class forfreshwaters. Class B waters are protected for primary recreation including frequent, organizedswimming. Water quality standards applicable to Class C apply to Class B waters in addition tomore stringent standards for bacterial pollution. “Tr” is a supplemental classification designed toprotect freshwaters for natural trout propagation and the survival of stocked trout, it does notdenote the presence of trout in a stream. Trout water (Tr) sections of Class B and C waters retainall respective water quality standards with the addition of more stringent standards for dissolvedoxygen, temperature, turbidity and chlorine.Figure 2.4: Use Classifications forstreams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 10

To determine the biological health of streams, DWQ evaluates the composition and diversity ofstream benthic macroinvertebrate communities every five years. These communities can provideimportant information about water quality stressors such as excessive nutrients, toxicants, andsediment pollution. In addition, macroinvertebrates and fish communities respond to the qualityof in-stream habitat, which is influenced by factors such as sedimentation. Thus, biologicalcommunities are reflections of stream integrity as a whole.Figure 2.5 shows the use-support rating assigned by DWQ for streams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed and the location of the five biological monitoring sites that DWQ sampled in 1997.Streams rated as either Not Supporting or Partially Supporting are considered impaired by theDWQ. <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>, Bat Fork and Clear <strong>Creek</strong> are listed on the state’s 303(d) List of ImpairedWaterbodies as Biologically Impaired Waters with no identified cause of impairment. One goalof the DWQ <strong>Watershed</strong> Assessment and <strong>Restoration</strong> Project (WARP) is to determine the causeof impairment of these streams. A summary of the data collected as part of the WARP study ispresented in Section 2.5.3. A complete summary of the DWQ Use Support Ratings and StreamUse Classifications for the French Broad River Basin, including the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed isavailable at http://h2o.enr.state.nc.us/basinwide/french/frenchbroad_wq_management_plan.htm.Figure 2.5: Use-support Ratings forstreams in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 11

2.5.3 DWQ’s <strong>Watershed</strong> Assessment and <strong>Restoration</strong> Project (WARP)In 2000, WARP launched a comprehensive assessment of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed to: 1)determine the most likely causes of biological impairment; 2) identify the major watershedactivities and pollution sources; and 3) outline a general watershed strategy that recommendsrestoration activities and best management practices (BMPs) to address the identified problems.As part of this assessment, WARP conducted a wide range of data collection activities, includingbenthic macroinvertebrate and water quality sampling, which are summarized in this section. Adetailed description of all their data collection methods as well as an analysis of their findings ispresented in the report titled Biological Impairment in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> (DWQ, 2003).Biological Sampling: WARP conducted biological sampling at 23 sites in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed and two reference sites outside the watershed between July 2000 and October 2001(Figure 2.6). WARP used benthic macroinvertebrate communities to characterize steam health.WARP evaluated a number of community characteristics, including diversity, pollution toleranceof the community as a whole, and species composition, to determine community health and thetypes of pollution impacting the streams. In addition to gathering data at known problem sites inthe watershed, WARP also collected samples at reference sites to establish benchmarks forhealthy biological communities and conducted habitat assessments at all sites to determine if thelack of habitat might also be a potential source of stress for these communities. Habitat scoresconsidered channel modifications, in-stream habitat (such as leafpacks, sticks, large woodydebris and rocks), sedimentation, riparian zone integrity, and riffle and pool frequency.WARP found that thehealthiest communities are inheadwater streams withadequate habitat that drainforested areas of thewatershed—Laurel Fork,upper Cox <strong>Creek</strong> and Harper<strong>Creek</strong> in the Clear <strong>Creek</strong>subwatershed and upper <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> above Walnut CoveRoad. Degraded benthiccommunities were found atalmost all other sample sites.Figure 2.6: WARP BiologicalMonitoring SitesDegraded biologicalcommunities were reportedfrom the urban portions of thewatershed, including DevilsFork at US 64 and <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>at 7 th Avenue (in<strong>Henderson</strong>ville). Habitatscores were very low in theseurban areas and likelycontributed to communitySection 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 12

degradation. In addition, the WARP study suggested that the high velocity and volume ofstormwater runoff generated by urban development scour stream channels, removing key habitatsuch as leafpacks and woody debris.Many of the biological sampling sites showed biological communities exposed to periodic toxicstress, most notably the sites downstream from large areas of apple orchards and row crops.Suspecting that pesticides might be impacting communities in lower Clear <strong>Creek</strong> and DevilsFork, WARP sampled these sites before, during and after the growing season. Figure 2.7illustrates the benthic community status at the biological sampling sites in the Clear <strong>Creek</strong> andDevils Fork subwatersheds and their proximity to orchards and row crops.A number of impacts other than toxicity likely influence the benthic communities at some sites.Benthic community analysis for Clear <strong>Creek</strong> at Mills Gap Road and both sites on Devils Forkshowed signs of organic enrichment or high nutrients. WARP also determined that in upper <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> and in many areas throughout the watershed, excess sedimentation exacerbates many ofthe primary causes of impairment.Figure 2.7: Apple orchards, row crops, andbenthic macroinvertebrate communities in theClear <strong>Creek</strong> and Devils Fork Subwatersheds.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 13

Chemical Water Quality Sampling: In addition to biological sampling, WARP also conductedextensive chemical water quality sampling to characterize water quality conditions in thewatershed and to evaluate whether chemical and physical conditions might be negativelyaffecting benthic communities. WARP established five sampling stations at the downstreamends of the subwatersheds and evaluated these sites monthly for a standard set of parametersincluding pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, metals, turbidity, and nutrients. Samples werecollected during both baseflow and stormflow periods. WARP also collected grab samples at anumber of sites in the watershed with known biological impairment. The purpose of the grabsamples was to assess potential chemical stressors such as pesticides, hydrocarbons and volatileorganic pollutants. Figure 2. 9 illustrates the location of WARP water quality sampling sitesacross the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed.WARP chemical water qualitymonitoring data indicated thatmany streams in the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> watershed includingupper and lower <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>,Clear <strong>Creek</strong>, Devils Fork, andBat Fork have higher nutrientand specific conductancelevels than expected forunpolluted streams in themountains. However, theselevels were not high enough toaffect biological communitiesor exceed NC’s standard oraction levels. Dissolvedoxygen levels in these streamswere adequate for aquatic life.In upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> and BatFork, fecal coliform bacterialevels were above the NCstandards of 200colonies/100mL. Althoughfecal coliform does not affectbiological communities, it canindicate the presence of virusesand pathogens that pose a riskto human health.Figure 2.8: Location of WARPwater chemistry sampling sites.Water samples taken during storms in the Clear <strong>Creek</strong> watershed had levels of insecticides thatare above ecological screening benchmarks and may cause sub-lethal impacts to aquatic insects.Bed sediment samples collected from upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> and Clear <strong>Creek</strong> provided evidence ofboth current and past use pesticide inputs. WARP identified pesticides as a cause of biologicalimpairment in these streams.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 14

WARP also evaluated selected metals concentrations in the watershed including cadmium,copper, lead, silver and zinc. Median metal values for baseflow samples collected by WARPwere generally below NC’s standards or benchmark levels. However, some stormflow samplesexceeded the benchmark levels for cadmium, copper, lead and/or zinc. Bioassay results fromthese samples indicated that these metal levels were not acutely toxic; however, results from aDevils Fork sample taken below a large commercial area showed acute toxicity, likely due tohigh copper, lead, and zinc concentrations. For a more detailed discussion of the WARPmonitoring protocol, sampling results and analysis, see the report titled Biological Impairment inthe <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>, 2003.2.5.4 Volunteer Water Information NetworkThe Volunteer Water Information Network (VWIN) monitors 33 sites in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>monthly for a wide range of water quality parameters including sediment, water clarity, pH,alkalinity, conductivity, heavy metals, and nutrients. Nine of these sites are located in the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> watershed (Figure 2.9). VWIN has monitored five of these sites monthly for nine yearsand the other three for over three years. This information is valuable in assessing current waterquality conditions and trends in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed.As shown in Figure 2.9, noneof the sites monitored byVWIN in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed rate excellent, butthree rate good. The remainingsites are either average (3),below average (2) or poor (1).To determine these ratings,VWIN compares nutrient,metals, and sediment values atthese sites to a regionalaverage for Western NorthCarolina. The regional averageis a composite score developedfrom VWIN monitoring effortsin <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> as wellas other western counties.Figure 2.9: Water Quality rating for VWINmonitoring sites in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong>.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 15

Good Sites: Consistent with the WARP study, the most upstream sites show fewer water qualityproblems than sites located in the more developed areas of the watershed. However, even at thegood sites, VWIN noted that nutrient concentrations at the Berea Church Road site have beenunusually high at times and that turbidity, conductivity, lead, and all three nutrient levels at Clear<strong>Creek</strong> at Apple Valley Road are increasing over time. VWIN concludes that the increasingturbidity levels are probably the result of escalating land disturbing activities.Average Sites: VWIN rates three sites in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed, Brittain <strong>Creek</strong>, Bat Fork<strong>Creek</strong>, and <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> at 7th Avenue as average. VWIN data indicate that conductivity levelsand heavy metals concentrations in Brittain <strong>Creek</strong> have been high at times and construction sitesmay be the greatest contributor of sediment to the creek during rains. The site on <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> at7th Avenue shows high concentrations of zinc probably due to road runoff and elevated nutrientconcentrations that may be coming from upstream sources. Diverting wastewater effluent fromthe GE plant to the <strong>Henderson</strong>ville wastewater treatment plant has helped to improve waterquality in Bat Fork, however nutrients and conductivity levels continue to be abnormally high.VWIN suggests that livestock may be the main source of nutrients to Bat Fork.Below Average Sites: VWIN rates Devil's Fork and Clear <strong>Creek</strong> at Nix Road (the downstreamsite on Clear <strong>Creek</strong>) below average. The nutrient and conductivity levels measured at Devil'sFork suggest that agriculture may be the most important source of pollutants to this stream. Bothof these streams have a heavy build-up of sediment in the downstream areas indicating thaterosion and runoff, including sediment pollution from land disturbing activities, have probablybeen impacting these streams for a long time.Poor Sites: <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> at North Rugby Road is one of three sites in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> thatrates poor. This site has consistently rated poor throughout the nine years of analysis. Nutrientconcentrations are much higher than average and water clarity is consistently poor. Nutrientconcentrations increase when stream flow decreases indicating a point-source for thesepollutants. Clear <strong>Creek</strong> shows serious problems with sedimentation and VWIN indicates thatland disturbing activities are probably a significant factor.2.5.5 Channel and Riparian Buffer ConditionChannel and buffer condition are important indicators of stream habitat and watershed health.Severely eroded streams produce significant quantities of sediment that are carried and depositeddownstream where they smother aquatic habitat. In some cases, channels become so deep andwide that the stream can no longer access the flood plain during a significant storm eventincreasing the likelihood of flooding downstream areas. WARP walked many miles of stream inthe <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed to document channel and riparian buffer condition, however this is avery time intensive effort and they were not able to observe every stream in the watershed. Aspart of the IPSI, TVA also evaluated channel and buffer conditions using aerial photography.These data are useful for documenting areas of the watershed with eroding streambanks andinadequate riparian buffers as well as streams channels that have been altered from their naturalstate.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 16

Channelized Streams: Channelization, or the straightening of streams, was a common practicein the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed to improve drainage and increase valuable floodplain areas forfarming. This practice destroys stream habitat by eliminating riffles and pools and meanderbends. The practice also dramatically affects the watershed hydrology by deepening channels,lowering the water table and increasing the stress on streambanks during storm events. Overtime, channelized streams can become very deep and overly wide with almost verticalstreambanks that can collapse sending large quantities of sediment directly into the stream. If thestreams become very incised, they will no longer over top their banks during storm eventsincreasing the volume and velocity of stormwater to downstream areas.Historical topographic and parcelmaps reveal that large-scalechannelization of <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>occurred between 1840 and 1890(Figure 2.10). Many tributaries to<strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>, including Bat Forkand Devils Fork, were alsochannelized. Major floods of1916, 1940, and 1964 caused muchconcern, leading to a number ofstream channelization anddredging projects aimed atminimizing flooding problems.Figure 2.10: Map of <strong>Henderson</strong>ville showing <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> prior to channelization.Table 2.3 illustrates the percentageof stream miles by subwatersheddelineated as channelized by theTVA IPSI. Over 50% of thenatural channels and aquatichabitat of Bat Fork and DevilsFork have been significantlyaltered by this practice. Biologicalmonitoring data collected byWARP in these areas suggests thatloss of habitat in these areas could be impacting the benthic communities in these subwatersheds.Eroding Streambanks: Although severe streambank erosion may be limited to short streamreaches, the sediment pollution from these eroding banks can have impacts throughout thewatershed. The sources of excess sedimentation noted in stream channels throughout the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> watershed are often not readily apparent because the sediment is from erodingstreambanks, and it is then transported and deposited downstream. Table 2.3 illustrates thepercentage of streambank miles that are eroding in each subwatershed as determined by the TVAIPSI from aerial photography. Field assessments conducted by WARP staff suggest that theseestimates are conservative probably due to the limitations of determining eroding banks fromaerial photos. Although the TVA IPSI data indicate that only 18% of the streams in the Clear<strong>Creek</strong> subwatershed are eroding, a more detailed analysis of these data show that the impact ofSection 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 17

eroding streambanks is more significant in some areas of the watershed. In the Lewis <strong>Creek</strong> and<strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> drainages, 37% and 25% of the streams are severely eroding. There are manypotential factors that exacerbate streambank erosion including channelization, a lack of riparianvegetation to stabilize banks and cattle with direct access to streams. Locating eroding streamsbanks is a first step to addressing this problem; understanding the factors that contribute to theproblem requires a more detailed analysis.SubwatershedTable 2.3: Channelization and Buffers in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershedPercentage of Subwatershed Stream MilesChannelizedstreamsErodingStreambanks*Adequate Buffers onBoth Banks*Bat Fork 56% 6% 15%Clear <strong>Creek</strong> 28% 18% 11%Devils Fork 55% 18% 2%Upper <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> 18% 12% 12%Lower <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> 28% 13% 9%Total <strong>Watershed</strong> 33% 14% 11%*Determined for a subset of streams (44% of total) that have a larger drainage area;adequate buffers are those with >= 30 ft of woody vegetation with >= 66% crown cover.Riparian Buffer Condition: As shown in Table 2.4, very few of the larger streams in the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> watershed have adequate riparian buffers. Riparian buffers have many importantwatershed functions. The deep roots of riparian vegetation help to stabilize streambanks andreduce erosion. Overhanging tree limbs shade streams and keep waters cool in the summer toprotect fish and other aquatic life. Adequately sized riparian buffers can also filter pollutantssuch as nutrients and sediment pollution that runs off adjacent fields and parking lots. Riparianbuffers also provide a protected corridor for wildlife migration. For all these reasons, riparianbuffer condition is an important indicator of stream health.TVA IPSI data provide information about the width and vegetation type and condition of riparianbuffers for all streams deemed perennial. These “perennial” streams are a subset of streams(only 44% of the total stream miles identified by the IPSI) that have larger drainage areas and arean underestimate of true perennial stream miles. For this report, adequate buffers weredetermined as those with woody vegetation with at least 66% crown cover and a width of >30 ft.In general, adequate buffers are present along upper sections of the tributaries that drain theforested northern ridge. In the lower gradient areas that are primarily in agriculture, there aresmall stream sections that have adequate buffers in small forested patches. Based on thisassessment, the current quality and distribution of adequate riparian buffers in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed is too limited to protect water quality and promote good aquatic habitat.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 18

2.6 Local Water Quality Initiatives2.6.1 Local Environmental OrdinancesA set of state and local regulatory programs impact development and water quality protection inthe <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed, the most important of which are described below.<strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> Ordinances• Subdivision Ordinance and the Manufactured Home Park Ordinance: These ordinancesrequire that stormwater drainage facilities be constructed to minimize erosion andsedimentation, minimize flooding, and avoid excessive discharge; however,specifications for post-development stormwater discharge volume and rate are notaddressed. The Subdivision Ordinance requires that structures built upon lots withinnewly platted subdivisions must remain 30 feet from the edge of any blue line streams (asindicated on USGS 1:24,000 Topographic Maps). However, the ordinance does notrequire that the area within this setback remain vegetated or permeable to water.• Water Supply <strong>Watershed</strong> Protection Ordinance: This ordinance delineates the uses anddevelopment of land and structures in water supply watersheds within <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>in order to maintain the high quality of surface water; however, no streams in the <strong>Mud</strong><strong>Creek</strong> watershed fall within this ordinance.• Farmland Preservation: This ordinance encourages the voluntary preservation andprotection of farmland from non-farm development.<strong>Henderson</strong>ville Ordinances• Floodway and floodway fringe development. Development is limited in the floodway andfloodway fringe in order to minimize public and private losses due to flood conditions. Itprovides guidance to control the alteration of natural floodplains, stream channels, andnatural protective barriers involved in the accumulation of flood waters, including filling,grading, dredging, or other development which may increase erosion or flood damage.Redevelopment in the floodway and fringe is permissible provided there is no loss offlood storage and the project utilizes BMPs to reduce post-redevelopment stormwater rateif feasible.• Stormwater management. Any development that includes impervious surfaces greater orequal to 0.5 acres must submit a stormwater management plan with stormwater controls.Post-development runoff rate must not exceed the pre-development rate.• Natural Resources Protection Ordinance. This ordinance contains a stream bufferprotection standard that requires protection of a 50 foot buffer on both sides of blue linestreams identified on the current USGS quadrangle maps. Existing uses of the bufferzone are allowed. The 50 foot buffer is divided into two zones—a 30 foot area ofundisturbed vegetation adjacent to the channel followed by a 20 foot belt of eithermanaged or unmanaged vegetation.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 19

Flat Rock Ordinances• Subdivision buffer requirement. This requires protection of a 50 foot set back onperennial streams, lakes, and wetlands as they appear on USGS topographic maps; thesetback is divided into two areas—a 25 foot zone of natural vegetation adjacent to thechannel followed by a 25 foot belt of either managed or natural vegetation. Perennialstreams not on a USGS topo, require a 10 foot buffer of natural vegetation.• Floodplain ordinance. No structures, with some exceptions, or fill are allowed in the 100year floodplain.• Stormwater management. Both subdivisions and other types of commercial andresidential developments are required to construct stormwater drainage facilities toprevent downstream erosion/sedimentation and follow existing natural drainage. Wherefeasible, stormwater discharge points must discharge through vegetated areas. Inaddition, commercial and residential developments (excluding subdivisions) are requiredto have stormwater controls to insure that post-development stormwater runoff rates donot exceed pre-development rates.2.6.2 Land Use <strong>Plan</strong>ning and ZoningLocal governments use zoning and land use planning to guide growth, ensure adequateinfrastructure and services and to protect environmental resources. Local zoning ordinances area good indicator for how an area, like the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed, might grow and develop andhow this growth might impact water quality. Table 2.5 summarizes the current zoning in the<strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. The zoning categories used in Table 2.5 generalize some 63 distinctzoning classifications of the five governmental entities with zoning authority in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>watershed.The “traditional” zoning districts, such as residential, commercial and industrial, account formore than 43% of the total <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. Each of these zoning districts containselements regulating lot size, structure size, and property line setbacks. To the extent that landuse affects water quality, each of these districts can have considerable positive and negativeimplications for water quality. Most districts regulate the size of the lot, thus affecting densityand potentially the degree of urban runoff. However, none of the districts regulate the amount ofimpervious surface or require permanent measures to control storm water runoff. Over 78% ofthe watershed falls within the zoning jurisdiction of <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>, with over 54% of thewatershed falling within the <strong>County</strong>’s Open Use Zoning District. Through issuance of a specialuse permit, open use zoning allows for many land uses, such as mining and extraction operationsand junkyards, that could pose a threat to water quality. Given the flexibility inherent in OpenUse Zoning, it is difficult to project the potential impacts to water quality from futuredevelopment in the watershed.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 20

Table 2.4: Summary of Zoning in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed.Generalized ZoningCategoryAcres PerCategoryPercentage of<strong>Watershed</strong> inZoning CategoryCommercial 3,295 5%Industrial 1,138 2%ResidentialHigh Density 1,006 1%Medium Density 10,929 15%Low Density 15,045 21%Open Use Zoning 39,071 54%Open Water 43

ECO has coordinated the VWIN program in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> in conjunction with EQI formore than a decade, providing trained volunteers to sample 33 sites on 28 streams each month(see paragraph 2.6.5). Monthly sample data and the VWIN annual report are distributedby ECO to elected officials in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> and the public. Where significant problems arenoted, ECO makes every effort to follow up with landowners or proper authorities to rectify andimprove sample results.A biological monitoring program in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> streams, begun by ECO in 2001, isconducted semi-annually on seven sites in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. The data gathered by thetrained volunteers on these and other sites will be included in annual VWIN reports beginningwith the 2001 report.An annual community-wide stream cleaning project -- NC Big Sweep – is also coordinated in<strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> by ECO. On the third Saturday in September each year, many volunteerspitch in to clean debris and trash from local waterways as part of the statewide litter removalprogram. For several years, the project in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> has focused oncleaning <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> and its major tributaries.In addition, ECO presents regular public programs on water quality issues, especially focusingon ways to reduce sedimentation and ways for homeowners to have wildlife-friendly yards andgardens without using fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides. ECO sponsors forums andworkshops on a number of water quality topics throughout the year.2.6.5 Volunteer Water Information Network (VWIN)VWIN is a water quality monitoring program run by citizens and the Environmental QualityInstitute (EQI) at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. Volunteers collect samples atnine locations in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed monthly. Samples are sent to EQI for analysis oftwelve parameters, including nutrients, metals, and turbidity. VWIN monitors over 200 streamand lake sites monthly throughout Western North Carolina. Local volunteers collect samples atspecified sites on a given day each month, and samples are delivered to EQI for analysis. VWINprepares an annual report for each area at the end of the monitoring year. The annual reportincludes comparisons of each site and each area with all sites analyzed in the mountain region.Local governments and organizations can use this information to compare similar situations andbetter recognize regional issues and develop regional solutions. Trend analysis is also carriedout on sites that have been monitored over a period of years. This provides information onchanging water quality over time and season.2.6.6 Southside Development InitiativeIn the summer of 2002 the City of <strong>Henderson</strong>ville engaged The Lawrence Group, town plannersand architects, to prepare a master plan for the City’s Southside, a 195-acre area centered on theintersection of U.S. Highways 25 and 176. Most of the area lies within the 100-year flood plainof <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>; however, it was heavily developed prior to the City’s participation in the FederalEmergency Management Agency (FEMA) program. <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> itself bisects the Southside,crossing under U.S. 25 just north of its intersection with U.S. 176.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 22

The Lawrence Group facilitated a week-long design charette in September, soliciting input froma wide range of “stakeholders”. The end-product of that process is a document called the<strong>Henderson</strong>ville Southside Development Initiative (SDI) which provides a vision for the futureredevelopment of this area. The SDI <strong>Plan</strong> is intended to provide a clear framework for theredevelopment of the Southside through a series of incremental, private and public developmentdecisions.Included within the Southside study area are two large tracts totaling 26.5 acres which, withinthe last year, the City has acquired with assistance from the North Carolina Wetlands <strong>Restoration</strong>Program (WRP). The <strong>Plan</strong> noted the importance of these parcels to the Southside DevelopmentInitiative and encouraged the City to continue to work with WRP to develop wetlands restorationprograms and to assist with flood mitigation. The City has entered into a memorandum ofunderstanding with WRP for the accomplishment of these restoration projects.2.6.7 Apple Country GreenwaysThe Apple Country Greenway Commission is a governmental organization created by aninterlocal agreement between all five <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> local governments. In 2001, theCommission completed a greenway masterplan for <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong>. The Oklawaha Trailproject, adjacent to <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong>, is already underway. Greenways located in riparian areas canhelp to improve habitat and water quality by protecting riparian areas from development.Greenways can also raise public awareness about water quality and stream condition. One goalof the Apple Country Greenway Commission is to design a plan that preserves, promotes andenhances environmental assets. To accomplish this goal, they laid out a number of objectivesthat are very consistent with the goals of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong> <strong>Restoration</strong> Council. Theseinclude:• Encourage localities to include greenways as a flood reduction strategy in their stormwaterregulations.• Develop a countywide strategy for protecting natural stream corridors and other open space,plus a mitigation program for addressing resources that have been adversely altered by landdevelopment.• Use areas adjacent to greenways as natural areas that protect, maintain, or restore naturalvegetation and aquatic and wildlife habitats.2.6.8 Carolina Mountain Land ConservancyThe Carolina Mountain Land Conservancy (CMLC) is a nonprofit organization that works todirectly protect the natural diversity and beauty of western North Carolina by preservingsignificant natural lands and scenic areas. Founded in 1994, CMLC has helped protect morethan 8,600 acres of land in <strong>Henderson</strong>, Transylvania and neighboring counties.CMLC is pursuing funds to acquire voluntary donated conservation easements on key propertiesin the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. CMLC intends to work in concert with the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> <strong>Watershed</strong><strong>Restoration</strong> Council’s efforts by preserving creeks and streams with existing high quality buffersand intact forests critical to maintaining watershed quality in the future. CMLC identified fourSection 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 23

areas as the most significant areas for protection in terms of water quality preservation andnatural heritage protection in the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. These areas are described below.Bearwallow Highlands: The Bearwallow Highlands, a rugged series of peaks and ridges, formthe northwestern boundary of the <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. Bearwallow Mountain is the tallestpeak in <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> outside the Pisgah National Forest. This area represents an importantpart of the natural and cultural heritage of the region.Floodplain/Agricultural: The <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> and Clear <strong>Creek</strong> valleys have a long-standing historyof productive agricultural use. In particular, the orchards of northeast <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> alongthe Clear <strong>Creek</strong> and its tributaries have historically brought the county the distinction of thebeing the largest apple producer in North Carolina.West <strong>Henderson</strong> Camps: Western <strong>Henderson</strong> <strong>County</strong> has for many years been home to acluster of summer camps, and retreat and conference centers. Children and families from aroundand beyond the state retain fond associations of a summertime experience amid the naturalbeauty of this area.Flat Rock Natural Heritage: The wetlands of the French Broad and <strong>Mud</strong> <strong>Creek</strong> systemsexhibit more community diversity than those of any other region of western North Carolina.Their broad floodplains, oxbows, backwaters, and bogs provide habitat for numerous plantspecies that are often uncommon or non-existent in other mountain counties.2.6.9 French Broad River Training <strong>Center</strong>The NCSU Cooperative Extension (CE) is also playing a significant role in developing BMPdemonstration projects, educating the public and landowners, and conducting training sessionsfor professionals in the region. A stormwater wetland was installed at a new container nursery inthe Clear <strong>Creek</strong> watershed. This project was funded by the CE’s Mountain Nurseries – Keepingthe French Broad Clean Project. The CE’s Upper French Broad River Riparian <strong>Restoration</strong> andProtection Project is working with willing landowners to restore riparian buffers along the Riverand its tributaries in <strong>Henderson</strong> and Transylvania counties. The Training <strong>Center</strong> has conductedregional training sessions on watershed and floodplain management, stormwater and erosioncontrol, low impact development, conservation easements and riparian buffer restoration.Section 2: <strong>Watershed</strong> Characterization Page 24