Parenting in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit - Carlos Haya

Parenting in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit - Carlos Haya

Parenting in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit - Carlos Haya

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

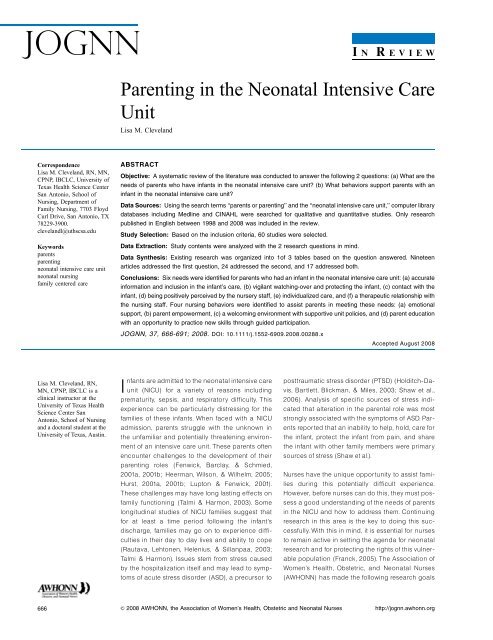

JOGNN I N R EVIEW<strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong><strong>Unit</strong>Lisa M. ClevelandCorrespondenceLisa M. Cleveland, RN, MN,CPNP, IBCLC, University ofTexas Health Science CenterSan Antonio, School ofNurs<strong>in</strong>g, Department ofFamily Nurs<strong>in</strong>g, 7703 FloydCurl Drive, San Antonio, TX78229-3900.clevelandl@uthscsa.eduKeywordsparentsparent<strong>in</strong>gneonatal <strong>in</strong>tensive care unitneonatal nurs<strong>in</strong>gfamily centered careABSTRACTObjective: A systematic review of <strong>the</strong> literature was conducted to answer <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g 2 questions: (a) What are <strong>the</strong>needs of parents who have <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> neonatal <strong>in</strong>tensive care unit? (b) What behaviors support parents with an<strong>in</strong>fant <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> neonatal <strong>in</strong>tensive care unit?Data Sources: Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> search terms ‘‘parents or parent<strong>in</strong>g’’ and <strong>the</strong> ‘‘neonatal <strong>in</strong>tensive care unit,’’ computer librarydatabases <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Medl<strong>in</strong>e and CINAHL were searched for qualitative and quantitative studies. Only researchpublished <strong>in</strong> English between 1998 and 2008 was <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> review.Study Selection: Based on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusion criteria, 60 studies were selected.Data Extraction: Study contents were analyzed with <strong>the</strong> 2 research questions <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d.Data Syn<strong>the</strong>sis: Exist<strong>in</strong>g research was organized <strong>in</strong>to 1of 3 tables based on <strong>the</strong> question answered. N<strong>in</strong>eteenarticles addressed <strong>the</strong> first question, 24 addressed <strong>the</strong> second, and 17 addressed both.Conclusions: Six needs were identified for parents who had an <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> neonatal <strong>in</strong>tensive care unit: (a) accurate<strong>in</strong>formation and <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’s care, (b) vigilant watch<strong>in</strong>g-over and protect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant, (c) contact with <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>fant, (d) be<strong>in</strong>g positively perceived by <strong>the</strong> nursery staff, (e) <strong>in</strong>dividualized care, and (f) a <strong>the</strong>rapeutic relationship with<strong>the</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g staff. Four nurs<strong>in</strong>g behaviors were identified to assist parents <strong>in</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se needs: (a) emotionalsupport, (b) parent empowerment, (c) a welcom<strong>in</strong>g environment with supportive unit policies, and (d) parent educationwith an opportunity to practice new skills through guided participation.JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.xAccepted August 2008Lisa M. Cleveland, RN,MN, CPNP, IBCLC is acl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>in</strong>structor at <strong>the</strong>University of Texas HealthScience Center SanAntonio, School of Nurs<strong>in</strong>gand a doctoral student at <strong>the</strong>University of Texas, Aust<strong>in</strong>.Infants are admitted to <strong>the</strong> neonatal <strong>in</strong>tensive careunit (NICU) for a variety of reasons <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gprematurity, sepsis, and respiratory di⁄culty. Thisexperience can be particularly distress<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>the</strong>families of <strong>the</strong>se <strong>in</strong>fants. When faced with a NICUadmission, parents struggle with <strong>the</strong> unknown <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> unfamiliar and potentially threaten<strong>in</strong>g environmentof an <strong>in</strong>tensive care unit. These parents oftenencounter challenges to <strong>the</strong> development of <strong>the</strong>irparent<strong>in</strong>g roles (Fenwick, Barclay, & Schmied,2001a, 2001b; Heerman, Wilson, & Wilhelm, 2005;Hurst, 2001a, 2001b; Lupton & Fenwick, 2001).These challenges may have long last<strong>in</strong>g e¡ects onfamily function<strong>in</strong>g (Talmi & Harmon, 2003). Somelongitud<strong>in</strong>al studies of NICU families suggest thatfor at least a time period follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’sdischarge, families may go on to experience di⁄culties<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir day to day lives and ability to cope(Rautava, Lehtonen, Helenius, & Sillanpaa, 2003;Talmi & Harmon). Issues stem from stress causedby <strong>the</strong> hospitalization itself and may lead to symptomsof acute stress disorder (ASD), a precursor toposttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Holditch-Davis,Bartlett, Blickman, & Miles, 2003; Shaw et al.,2006). Analysis of speci¢c sources of stress <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat alteration <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> parental role was moststrongly associated with <strong>the</strong> symptoms of ASD. Parentsreported that an <strong>in</strong>ability to help, hold, care for<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant, protect <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant from pa<strong>in</strong>, and share<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant with o<strong>the</strong>r family members were primarysources of stress (Shaw et al.).Nurses have <strong>the</strong> unique opportunity to assist familiesdur<strong>in</strong>g this potentially di⁄cult experience.However, before nurses can do this, <strong>the</strong>y must possessa good understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> needs of parents<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU and how to address <strong>the</strong>m. Cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>gresearch <strong>in</strong> this area is <strong>the</strong> key to do<strong>in</strong>g this successfully.With this <strong>in</strong> m<strong>in</strong>d, it is essential for nursesto rema<strong>in</strong> active <strong>in</strong> sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> agenda for neonatalresearch and for protect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> rights of this vulnerablepopulation (Franck, 2005). The Association ofWomen’s Health, Obstetric, and <strong>Neonatal</strong> Nurses(AWHONN) has made <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g research goals666 & 2008 AWHONN, <strong>the</strong> Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and <strong>Neonatal</strong> Nurses http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWa priority: preterm and near-term <strong>in</strong>fants, reductionof disparities <strong>in</strong> low birth weight, <strong>the</strong> impact of technology<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU, and parent education(AWHONN, 2007). In addition, Harrison and colleaguessuggest numerous topics for neonatalresearch and pose <strong>the</strong> important questions: ‘‘Whatnurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>terventions help to reduce stressorsexperienced by families who have <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>NICU?’’ (p. 65) and ‘‘What <strong>in</strong>terventions help to promoteattachment and adaptive parent<strong>in</strong>g betweenparents and preterm <strong>in</strong>fants and between parentsand <strong>in</strong>fants with serious health problems?’’(Harrison,Lucas, & Franck, 2003, p. 65).Ano<strong>the</strong>r researcher <strong>in</strong> this area of study, Franck,claims that numerous topics <strong>in</strong> neonatal care, suchas parental stress <strong>in</strong> response to a NICU admission,have been well described <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature, but few of<strong>the</strong>se studies have been followed up with <strong>in</strong>terventionalmethods or cl<strong>in</strong>ical trials. Some areas ofneonatal care have been over-researched, such as<strong>the</strong> development of numerous neonatal pa<strong>in</strong> assessmenttools, while o<strong>the</strong>r important areas havebeen neglected (Franck, 2002). For example, studiesfocus<strong>in</strong>g on parental visitation and <strong>in</strong>volvement<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU were well researched dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 1980s,but little research on this topic has been conductedmore recently (Franck & Spencer, 2003). Therefore,<strong>the</strong> purpose of this literature review was to conductan <strong>in</strong>vestigation <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> current research on parent<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU with a particular emphasis onresearch methodology and design. All articles werecritically analyzed with two primary questions <strong>in</strong>m<strong>in</strong>d: (a) What are <strong>the</strong> needs of parents <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>NICU? (b) What nurs<strong>in</strong>g behaviors support parents<strong>in</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>se needs?MethodsA systematic review of both qualitative and quantitativeresearch was conducted to identify what isknown about <strong>the</strong> needs of NICU parents and whatbehaviors support <strong>the</strong>se parents. Both methods ofresearch were <strong>in</strong>cluded because of <strong>the</strong> potential foreach to contribute to a more complete understand<strong>in</strong>gof this topic. A systematic review was employedbecause it results <strong>in</strong> a scienti¢c, reproducible, summaryof orig<strong>in</strong>al research ¢nd<strong>in</strong>gs with clearlystated <strong>in</strong>clusion and exclusion criteria. This methodof review limits personal bias from <strong>the</strong> reviewer andcontributes to evidence-based nurs<strong>in</strong>g practice(Stevens, 2001; Whittemore & Kna£, 2005).The computer library databases Medl<strong>in</strong>e andCINAHL were searched for research studies publishedbetween 1998 and 2008. This time framewas selected due to <strong>the</strong> rapid advances <strong>in</strong> technologyand <strong>the</strong> chang<strong>in</strong>g environment of <strong>the</strong> NICU overthis time period. A review of <strong>the</strong> most current researchon parent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU was <strong>the</strong> aim of thisreview.To be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> this review, <strong>the</strong> studies had to beresearch, pr<strong>in</strong>ted <strong>in</strong> English, speci¢c to parent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> NICU, and speci¢c to <strong>the</strong> two research questionsthat were <strong>the</strong> focus of this review. Thecomb<strong>in</strong>ed search terms were ‘‘parents or parent<strong>in</strong>g’’and ‘‘neonatal <strong>in</strong>tensive care unit.’’ Two hundredand sixteen studies were obta<strong>in</strong>ed from Medl<strong>in</strong>eand ano<strong>the</strong>r 168 from CINAHL. Titles and abstractswere reviewed to determ<strong>in</strong>e if <strong>the</strong> studies met <strong>the</strong>stated criteria. If a determ<strong>in</strong>ation could not bemade <strong>in</strong> this manner, <strong>the</strong> article was retrieved andread before mak<strong>in</strong>g a decision. Thirty-seven studies(5 doctoral dissertations) meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> searchcriteria were selected from CINAHL and 16 wereselected from Medl<strong>in</strong>e. An additional 7 articlesmeet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> criteria were selected from <strong>the</strong> referencelists of articles already <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> review(Fenwick et al., 2001a, 2001b; Hurst, 2001a, 2001b;Pearson & Anderson, 2001; Peterson, Cohen, &Parsons, 2004; Schroeder & Pridham, 2006). Thesestudies were <strong>in</strong>cluded because <strong>the</strong>y met <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>clusioncriteria and were determ<strong>in</strong>ed to be relevant toanswer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> research questions. A total of 60studies were selected for review based on <strong>the</strong>search criteria.ResultsAfter carefully review<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> ¢nd<strong>in</strong>gs of each study,<strong>the</strong> author determ<strong>in</strong>ed that 19 studies addressedparent<strong>in</strong>g needs (see Table 1), 24 addressed supportivebehaviors (see Table 2), and 17 addressedboth (see Table 3). The studies were <strong>the</strong>n organizedaccord<strong>in</strong>g to research methodology. Of <strong>the</strong> 19with a focus on parent<strong>in</strong>g needs, 5 of <strong>the</strong> studies utilizedquantitative methods and 14 were qualitative.Of <strong>the</strong> studies address<strong>in</strong>g parent support <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>NICU, 19 were quantitative, 2 were mixed methods,and 3 were qualitative. The 17 studies address<strong>in</strong>gboth research questions <strong>in</strong>cluded 6 quantitativeand 11 qualitative studies (see Table 4). Also noteworthy,4 of <strong>the</strong> studies reviewed were written us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> same research data (Fenwick et al., 2001a,2001b; Fenwick, Barclay, & Schmied, 2002; Lupton& Fenwick, 2001). In a di¡erent <strong>in</strong>stance, Hurst(2001a, 2001b) utilized <strong>the</strong> same data baseto write both of her articles. Although <strong>the</strong> focusof each article was slightly di¡erent, what <strong>in</strong>itiallyappeared to be 6 separate studies was actuallyonly 2.JOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 667

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>Table 1: Parental Needs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUStudy and Year Purpose of Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsQuantitative Descriptive StudiesBialoskurskiet al. (2002)Explore <strong>the</strong> organization ofmaternal needs andpriorities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUPurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g of 209 mo<strong>the</strong>rsage 18-45<strong>Unit</strong>edK<strong>in</strong>gdomQuestionnaire with 2 self-assessmentsurveys: critical care maternal needs<strong>in</strong>ventory and a rank<strong>in</strong>g scale93% of mo<strong>the</strong>rs ranked receiv<strong>in</strong>g accurate<strong>in</strong>formation as a priority. Good communicationwith sta¡ was also important while self-relatedneeds were considered less importantJoseph et al.(2007)Identify perceived stress <strong>in</strong>fa<strong>the</strong>rs of surgical <strong>in</strong>fants22 fa<strong>the</strong>rs 18 years and older. Infantscategorized by condition: cardiac,respiratory, neurological anomaliesMid Atlantic<strong>Unit</strong>ed States22 item Parental Stressor Scale: InfantHospitalizationFa<strong>the</strong>rs’ stress was highest for Parental RoleAtta<strong>in</strong>ment and Infant Appearance and Behavior.Infant pa<strong>in</strong>, separation from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant, andbreath<strong>in</strong>g problems were most stressfulLam et al.(2007)Explore parents’ stress andperceptions of supportrelated to nurs<strong>in</strong>g behaviors63 parents, 76% mo<strong>the</strong>rs. (English,Arabic, and Ch<strong>in</strong>ese speak<strong>in</strong>g)<strong>in</strong>fants with cardiac or surgicalproblemsAustralia NICU nurs<strong>in</strong>g sta¡ behavior andcommunication subscale of <strong>the</strong> ParentalStress Scale and <strong>the</strong> Nurse Parent SupportToolSources of stress <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong>adequate <strong>in</strong>formationconcern<strong>in</strong>g tests and treatment and uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty if<strong>the</strong> nurse would call parents if <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’scondition changed. Stress and perceived supportwere moderatePunthmathari<strong>the</strong>t al. (2007)Compare <strong>the</strong> needs, needresponses, and needresponse satisfaction ofmo<strong>the</strong>rsPurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g of 420 mo<strong>the</strong>rs(140 from each hospital); mean agesof <strong>the</strong> 3 groups ranged from 25-28years3 hospitals <strong>in</strong>sou<strong>the</strong>rnThailand3 questionnaires developed by <strong>the</strong>researcherSigni¢cant di¡erences were identi¢ed betweengroups for needs, need responses, and needresponse satisfactionWard (2001) Identify <strong>the</strong> perceived needsof parentsConvenience sample of 52 parents (42mo<strong>the</strong>rs,10 fa<strong>the</strong>rs) mean age 25years, 56% White, 65% of <strong>in</strong>fantswith primary diagnosis ofprematurityMidwestern<strong>Unit</strong>ed StatesNICU Family Needs Inventory (NFNI)derived from <strong>the</strong> Critical <strong>Care</strong> FamilyNeeds Inventory (CCFNI)Assurance was most important and support wasleast important. Fa<strong>the</strong>rs ranked support,assurance and <strong>in</strong>formation needs signi¢cantlylower than mo<strong>the</strong>rs. Comfort and proximityneeds did not di¡er between mo<strong>the</strong>rs andfa<strong>the</strong>rs668 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 1. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy and Year Purpose of Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsQualitative StudiesArockiasamyet al. (2008)Understand <strong>the</strong> experiencesof fa<strong>the</strong>rs with seriously ill<strong>in</strong>fantsPurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g of fa<strong>the</strong>rs; 12White, 3 East Indian, and 1 AsianCanada Semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terview conducted by amale physician. Constant comparativecontent analysisLack of control with ¢ve sub<strong>the</strong>mes: world view,<strong>in</strong>formation, communication, roles and externalactivitiesBroeder (2003) Exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> process ofbecom<strong>in</strong>g a mo<strong>the</strong>r dur<strong>in</strong>ghospitalization anddischarge homePurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g; 8 mo<strong>the</strong>rs(White), 25-41 years old, no <strong>in</strong>fantanamoliesMidwestern<strong>Unit</strong>ed StatesSemi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviews every twoweeks dur<strong>in</strong>g hospitalization and monthlyfor 4 months follow<strong>in</strong>g discharge.Interpretive data analysisMo<strong>the</strong>rs wanted to rema<strong>in</strong> connected dur<strong>in</strong>gseparation from <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant while be<strong>in</strong>g preventedfrom hold<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>m. Gett<strong>in</strong>g to know<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant while <strong>the</strong> nurse was <strong>the</strong> primarycaretaker was a challengeErlandssonandFagerberg(2005)Describe how mo<strong>the</strong>rsexperienced <strong>the</strong> care and<strong>the</strong>ir own healthConvenience sample; 6 mo<strong>the</strong>rs ofNICU <strong>in</strong>fants approximately 2months after birth and afterdischarge from <strong>the</strong> hospitalSweden Semi-structured, open-ended, <strong>in</strong>terviewsfocus<strong>in</strong>g on <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>rs’ experience <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> co-care ward. Description, reduction,and higher level <strong>in</strong>variant mean<strong>in</strong>gsanalysisMo<strong>the</strong>rs wanted to be close to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants, be seen,and be part of a functional team. Theorganization/sta¡ prolonged <strong>the</strong> separation. Evenafter return<strong>in</strong>g home, mo<strong>the</strong>rs had di⁄cultydeal<strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> separationHeerman et al.(2005)Explore and describemo<strong>the</strong>rs’ experiences15 upper middle class, White mo<strong>the</strong>rs Midwestern<strong>Unit</strong>ed StatesInterviews of open-ended questions.Spradley’s doma<strong>in</strong> analysisMo<strong>the</strong>rs progressed from outsider to partnerthrough 4 major doma<strong>in</strong>s: focus, ownership,care giv<strong>in</strong>g, and voice. Mo<strong>the</strong>rs progress atdi¡erent rates and nurses can facilitate thisprocessHigg<strong>in</strong>s andDullow(2003)Explore <strong>the</strong> experiences ofparentsConvenience sample of parents 20-40years old with <strong>in</strong>fants of goodprognosisSou<strong>the</strong>asternAustraliaInterviews conducted post discharge Ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>me of parent<strong>in</strong>g from a distance.Three sub<strong>the</strong>mesof watchfulness, need<strong>in</strong>g to be near <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>fant, and feel<strong>in</strong>g useful <strong>in</strong>stead of uselessHolditch-Davisand Miles(1999)Determ<strong>in</strong>e how well mo<strong>the</strong>rs’experiences ¢t <strong>the</strong> PretermParental Distress Model31 mo<strong>the</strong>rs, <strong>in</strong>fant o1,500 g,mechanically ventilated or both.Average maternal age 5 29 years,86% were married,19 White,11African American, and 1 Asian<strong>Unit</strong>ed States Interviews at 6 months corrected gestationalage. Data analyzed us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oreticalframework as a guideMo<strong>the</strong>rs’ experiences were consistent with <strong>the</strong> 6sources of stress outl<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oreticalmodel; (a) pre-exist<strong>in</strong>g and concurrent personalfactors, (b) prenatal and per<strong>in</strong>atal experiences,(c) <strong>in</strong>fant illness, treatment, and appearance, (d)concern about <strong>in</strong>fant’s outcome, (e) loss of <strong>the</strong>parental role, and (f) healthcare providersJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 669

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>Table 1. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy and Year Purpose of Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsHurst (2003) Exam<strong>in</strong>e how resources toensure family centered carea¡ected <strong>the</strong> experience ofa Mexican Americanmo<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUOne bil<strong>in</strong>gual Mexican Americanmo<strong>the</strong>r (case study)Western <strong>Unit</strong>edStatesAudiotaped <strong>in</strong>terviews and ¢eld notes about<strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r’s experience analyzed us<strong>in</strong>gnarrative and content analysisInadequate resources <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU createdsituations where responsibilities such as<strong>in</strong>terpretation and transportation for o<strong>the</strong>rmo<strong>the</strong>rs were shifted to <strong>the</strong> participantHurst (2001a) Ga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to mo<strong>the</strong>rs’perceived needs andexplanation for <strong>the</strong>ir actionsPurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g; 12 Englishspeak<strong>in</strong>g mo<strong>the</strong>rs 20-43 years (7White, 4 Lat<strong>in</strong>a,1African American)Nor<strong>the</strong>rnCaliforniaBedside observation, audio-recordedconversations, and privately conducted<strong>in</strong>terviews. Thematic content analysis,constant comparative cod<strong>in</strong>g/classi¢cation, and narrative analysisMo<strong>the</strong>rs had <strong>in</strong>formational, <strong>in</strong>teractional, andemotional safety needs, <strong>the</strong>y negotiated actionswith healthcare providers, cautiously challengedauthority, and ga<strong>the</strong>red support from o<strong>the</strong>rmo<strong>the</strong>rs, friends and family. Fear of be<strong>in</strong>glabeled ‘‘di⁄cult’’ and ‘‘vigilance’’ were keyconceptsHurst (2001b) Explore mo<strong>the</strong>rs’ descriptionand <strong>in</strong>terpretation of <strong>the</strong>irexperienceSame data base as Hurst (2001a) Nor<strong>the</strong>rnCaliforniaSame as Hurst (2001a) Underly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mes of mo<strong>the</strong>rs ‘‘vigilantly watch<strong>in</strong>gover’’ <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants. Mo<strong>the</strong>rs were alert to issues ofsafety that might signal danger for <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant.Feared be<strong>in</strong>g labeled di⁄cult, and expressedconcerns over <strong>the</strong> lack of complete and accurate<strong>in</strong>formation provided, <strong>in</strong>adequate sta⁄ng andlack of cont<strong>in</strong>uity of careJamsa andJamsa (1998)Describe parents’experiences of <strong>the</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>gcare of critically ill <strong>in</strong>fantsPurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g; 7 mo<strong>the</strong>rs and 4fa<strong>the</strong>rs of full-term ill <strong>in</strong>fantsF<strong>in</strong>land Informal <strong>in</strong>terviews with preplanned openendedquestions. Inductive, contentanalysisParents found <strong>the</strong> NICU environment ‘‘shock<strong>in</strong>g’’and <strong>the</strong> technological environment made <strong>the</strong>mfeel like outsiders <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> care of <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fantsOrapiriyakulet al. (2007)Explore maternal attachment<strong>in</strong>Thai mo<strong>the</strong>rsPurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g of 15 mo<strong>the</strong>rsaged 16-42. Infants o37 weeksgestation, had no anomalies, andwere or had been mechanicallyventilatedThailand Interviews and observations. Constantcomparative method analysisMo<strong>the</strong>rs were ‘‘struggl<strong>in</strong>g to get connected’’composed of 4 phases: (a) establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>connections, (b) disrupt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> connections, (c)resum<strong>in</strong>g to get connected, and (d) becom<strong>in</strong>gconnected670 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 1. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy and Year Purpose of Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsTaylor-Huber(1998)Determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> mean<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong>experience of parent dyadswith <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU9 parent dyads, age 22-53 years, 8 of<strong>the</strong> 9 dyads were married. Nofur<strong>the</strong>r demographics wereprovided2levelIIINICUs<strong>in</strong> UtahThree parent dyads, unstructured,<strong>in</strong>terviews. Data analyzed for <strong>the</strong>mesAn overall <strong>the</strong>me of stress was identi¢ed with 4sub<strong>the</strong>mes: issues of trust, family roles andrelationships, parental role and authority, andparent-nurse relationships <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUTaylor-Johnson(1999)Explore <strong>the</strong> perceivedlearn<strong>in</strong>g needs of mo<strong>the</strong>rs<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU and afterdischargePurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g of 30 mo<strong>the</strong>rs,18-41 years (17 African American, 7White, and 6 Lat<strong>in</strong>a)Hospital andhomeUnstructured <strong>in</strong>terviews with ¢eld notes(no audiotapes)Learn<strong>in</strong>g needs <strong>in</strong>cluded baby basic care,breath<strong>in</strong>g, heart rate, medications, and monitorsWhitlow (2003) Explore <strong>in</strong>teractions andattachment <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUPurposive sampl<strong>in</strong>g of 13 mo<strong>the</strong>rs with<strong>in</strong>fants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU 1-17 years prior.(12 White,1 African American) 21-49yearsAL,TN, andGAQualitative <strong>in</strong>terview; heuristic analysis Mo<strong>the</strong>rs were <strong>in</strong>itially overwhelmed by <strong>the</strong> NICU.Adaptation was essential to <strong>in</strong>teraction with <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>fant. Mo<strong>the</strong>rs desired to hold <strong>in</strong>fants, acquireknowledge, and learn how to <strong>in</strong>teract with <strong>in</strong>fantsJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 671

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>Parents felt excluded from <strong>the</strong> care of <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants.After categoriz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> articles, conventional contentanalysis was used to more closely exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong>¢nd<strong>in</strong>gs of each study. This type of analysis allowedcategories to emerge from <strong>the</strong> data with <strong>the</strong> goal ofanswer<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> two research questions (Hsieh &Shannon, 2005). Based on <strong>the</strong> literature, six primaryneeds of parents <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU were identi¢ed. These<strong>in</strong>cluded: (a) accurate <strong>in</strong>formation and <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’s care and decision mak<strong>in</strong>g, (b) vigilantwatch<strong>in</strong>g-over and protect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant, (c) contactwith <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant, (d) be<strong>in</strong>g positively perceived by <strong>the</strong>nursery sta¡, (e) <strong>in</strong>dividualized care, and (f) reassuranceand a <strong>the</strong>rapeutic relationship with <strong>the</strong>nurs<strong>in</strong>g sta¡. Four supportive behaviors for assist<strong>in</strong>gparents that meet <strong>the</strong>se needs were alsoidenti¢ed. These <strong>in</strong>cluded: (a) emotional support,(b) parent empowerment, (c) a welcom<strong>in</strong>g environmentwith supportive unit policies, and (d) parenteducation with an opportunity to practice new skillsthrough guided participation. In <strong>the</strong> paragraphsthat follow, <strong>the</strong>se parent<strong>in</strong>g needs and supportivebehaviors will be discussed <strong>in</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r detail.What are <strong>the</strong> Needs of Parents WhoHave Infants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU?A Need for Accurate Information and Inclusion<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Infant’s <strong>Care</strong> and Decision Mak<strong>in</strong>gParents expressed a desire to receive accurate,understandable, <strong>in</strong>formation and wanted to participate<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> decision mak<strong>in</strong>g process (Alderson,Hawthorne, & Killen, 2006; Arockiasamy, Holsti, &Abersheim, 2008; Bialoskurski, Cox, & Wigg<strong>in</strong>s,2002; Gardner, Barrett, Coonan, Cox, & Roberson,2002; Hurst, 2001a, 2001b, 2003; Lam, Spence, &Halliday, 2007; Lubbe, 2005; Mok & Leung, 2006;Taylor-Huber,1998; Taylor-Johnson,1999; van Rooyen,Nomgqokwana, Kotze, & Carlson, 2006;Whitlow, 2003). They also wanted to be actively<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> care of <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants (Erlandsson &Fagerberg, 2005; Fenwick et al., 2001a; Heermanet al., 2005; Higg<strong>in</strong>s & Dullow, 2003; Holditch-Davis& Miles, 2000; Jamsa & Jamsa,1998; Lupton & Fenwick,2001; Orapiriyakul, Jirapaet, & Rodcumdee,2007; Pohlman, 2005;van Rooyen et al.; Wigert,Johansson, Berg, & Hellstrom, 2006). They voiceddistress over receiv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>accurate and/or <strong>in</strong>complete<strong>in</strong>formation perta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant’scondition (Hurst, 2001b). They felt as though <strong>the</strong>ywere parent<strong>in</strong>g from a distance and struggled withfeel<strong>in</strong>gs of uselessness while yearn<strong>in</strong>g to be useful<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant care (Higg<strong>in</strong>s & Dullow). Be<strong>in</strong>g able to providebasic care for <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant was identi¢ed ascritical (Heerman et al.). Some mo<strong>the</strong>rs stated thatbe<strong>in</strong>g able to provide care was a major turn<strong>in</strong>gpo<strong>in</strong>t, especially when <strong>the</strong>y began to feel that <strong>the</strong>yknew <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants better than <strong>the</strong> nurses did (Lupton& Fenwick).Unfortunately, some parents identi¢ed a sense ofbe<strong>in</strong>g excluded from <strong>the</strong> care of <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants. In alongitud<strong>in</strong>al study, Wigert et al. (2006) found thatmo<strong>the</strong>rs often felt like ‘‘<strong>in</strong>truders’’ <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU. Theyfelt that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant belonged to <strong>the</strong> caregiver. Thisexclusion from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’s care was associated withnegative maternal feel<strong>in</strong>gs that could last for severalyears follow<strong>in</strong>g discharge. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand,approaches that <strong>in</strong>volved encourag<strong>in</strong>g mo<strong>the</strong>rs toparticipate <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’s care, treat<strong>in</strong>g each mo<strong>the</strong>ras an <strong>in</strong>dividual, and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g e¡ective dialoguewith <strong>the</strong> nurses were found to be associated withmore positive maternal feel<strong>in</strong>gs (Wigert et al.).A Need to be Vigilant and to Watch Over andProtect <strong>the</strong> InfantAn underly<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>me of vigilance or watch<strong>in</strong>g over<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant was identi¢ed <strong>in</strong> several studies (Higg<strong>in</strong>s& Dullow, 2003; Hurst, 2001a, 2001b). Vigilance wasdescribed as a heightened level of watchfulness,<strong>in</strong>formation ga<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g, and re£ection on maternalfeel<strong>in</strong>gs (Hurst, 2001a). Mo<strong>the</strong>rs were alert for situationsthat signaled danger such as poor cont<strong>in</strong>uityof care, lack of attention to <strong>the</strong> baby, or suspect<strong>in</strong>gthat contra<strong>in</strong>dicated care was be<strong>in</strong>g provided(Hurst, 2001b). Parents felt as though <strong>the</strong>y neededto protect <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants from danger by oversee<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fants’ care. As <strong>the</strong>y started to form trust<strong>in</strong>grelationships with <strong>the</strong> nurses, this watchfulness beganto relax (Higg<strong>in</strong>s & Dullow). Frequent phonecalls to <strong>the</strong> NICU and <strong>the</strong> parent’s presence at <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>fant’s bedside were techniques parents used to‘‘safe guard’’ <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant (Hurst, 2001b).A Need for Contact With <strong>the</strong> InfantA need to be near <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant and to have physicalcontact was identi¢ed as important to parents(Broeder, 2003; Erlandsson & Fagerberg, 2005;Higg<strong>in</strong>s & Dullow, 2003; Joseph, Mackley, Davis,Spear, & Locke, 2007; Lupton & Fenwick, 2001; Orapiriyakulet al., 2007; Ward, 2001; Whitlow, 2003).Mo<strong>the</strong>rs yearned to hold <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants, but when thiswas not possible due to <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’s fragile condition,<strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>rs found comfort <strong>in</strong> sitt<strong>in</strong>g next to<strong>the</strong> bed touch<strong>in</strong>g and strok<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants. Provid<strong>in</strong>gbreast milk was viewed as a form of contact andwas desirable to mo<strong>the</strong>rs because <strong>the</strong>y felt this wassometh<strong>in</strong>g only <strong>the</strong>y could do for <strong>the</strong>ir babies.672 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 2: Parental Support <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUStudy andYear Purpose of <strong>the</strong> Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Intervention Design/Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsQuantitativeBrowneand Talmi(2005)Determ<strong>in</strong>e if a family based<strong>in</strong>tervention might a¡ectparent<strong>in</strong>g knowledge,behavior, and stressConvenience sample; 84mo<strong>the</strong>rs; mean age 5 24years;75% White,15%African American; 77% onpublic assistanceOklahoma Group I: demonstration and<strong>in</strong>teraction; Group II:education; Group III: controlQuasi-experimental. Subjectsrandomly assigned to one of 3groups; 2 experimental, onecontrol The Knowledge ofPreterm Infant Behavior Scale;Nurs<strong>in</strong>g Child AssessmentFeed<strong>in</strong>g Scale; <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong>Stress Index; Severity of IllnessScoreMo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> both experimentalgroups demonstrated greaterparent<strong>in</strong>g knowledge and<strong>in</strong>teractional behavior anddecreased stress whencompared to <strong>the</strong> control groupChristopheret al.(2000)Explore <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>£uence of socialsupport and perceived stresson a¡ectionate behavior107 mo<strong>the</strong>rs,13-21; 44%White non-Hispanic, 47%Black, 7% Native AmericanNorthCarol<strong>in</strong>aNone Descriptive, correlational. A 7item perceived stress scale,10item social support scale, and<strong>the</strong> A¡ectionate BehaviorsScale developed for this studyNei<strong>the</strong>r social support norperceived stress were relatedto a¡ectionate behaviors, andno statistical <strong>in</strong>teractionsbetween <strong>the</strong> three variableswere foundCorreiaet al.(2008)Characterize verbal contentsexpressed by <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>rs ofpreterm <strong>in</strong>fants attend<strong>in</strong>g apsychological support<strong>in</strong>terventionPurposive sample of 10mo<strong>the</strong>rs with cl<strong>in</strong>icalsymptoms of depressionsand anxiety and 10 without.Ages 14-39Brazil Weekly psychological<strong>in</strong>tervention sessionsdesigned to support mo<strong>the</strong>rsdur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants’hospitalizationsQuantitative, <strong>in</strong>terpretive.Structured cl<strong>in</strong>ical <strong>in</strong>terview-DSM-III-R, Beck DepressionInventory, State-Trait Anxiety<strong>in</strong>ventoryDepressed/anxious mo<strong>the</strong>rsexpressed more negativefeel<strong>in</strong>gs or reactions thanmo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> comparisongroupGlazebrooket al.(2007)Evaluate <strong>the</strong> e¡ect of aparent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tervention onmo<strong>the</strong>rs’ responsiveness and<strong>in</strong>fants’ neurobehavioraldevelopment <strong>in</strong> preterm<strong>in</strong>fants o32 weeks gestation233 mo<strong>the</strong>rs and <strong>in</strong>fants; 112<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention group,121 <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> control group.Mo<strong>the</strong>rs predom<strong>in</strong>antlyWhite, 24-35 years<strong>Unit</strong>edK<strong>in</strong>gdomA nurse delivered <strong>in</strong>terventionconsist<strong>in</strong>g of tactile and verbalactivities, observation, anddiscussionCluster, randomized, controlledtrial. <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Stress Indexshort-form; NeurobehavioralAssessment of <strong>the</strong> PretermInfant; Nurs<strong>in</strong>g ChildAssessment Teach<strong>in</strong>g Scale(NCATS); Home Observationfor Measurement of <strong>the</strong>Environment (HOME)No statistical di¡erence between<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention and controlgroups for stress, <strong>in</strong>fantneurobehavioral development,or NCATS and HOME scores at3 months post dischargeJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 673

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>Table 2. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of <strong>the</strong> Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Intervention Design/Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsHurst(2006)Indentify parent utilization andevaluation of parent supportservices (PSS)Convenience sample of 303families that used <strong>the</strong> PSS.90% mo<strong>the</strong>rs with meanage of 33.6 yearsWest Coast<strong>Unit</strong>edStatesNone Quantitative descriptive.Retrospective hospital recordsreviewed to identify familiesthat used PSS. An <strong>in</strong>vestigatordeveloped mailed survey toevaluate PSS e¡ectiveness.The <strong>in</strong>tervention improvedparents’ ability to criticallyappraise <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant’s behaviorand to respond appropriately78% utilized one form of supportexclusively while 18% used 2forms at <strong>the</strong> same time.Cont<strong>in</strong>uity was critical; groupsupport was more bene¢cialfor assist<strong>in</strong>g familiesJones et al.(2007)Explore mo<strong>the</strong>rs’ and fa<strong>the</strong>rs’perceptions of e¡ective and<strong>in</strong>e¡ective nursecommunicationConvenience sample of 20mo<strong>the</strong>rs and 13 fa<strong>the</strong>rsaged 28-41 yearsAustralia None Semi-structured <strong>in</strong>terviewsask<strong>in</strong>g parents about <strong>the</strong>irperceptions of e¡ective and<strong>in</strong>e¡ective communicationE¡ective communication wasaccommodat<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>cludednurses ask<strong>in</strong>g questions,encourag<strong>in</strong>g parents to askquestions, <strong>in</strong>formal chatt<strong>in</strong>gand conversation about <strong>the</strong>baby. It was also emotional,warm and empa<strong>the</strong>tic.Ine¡ective communication wasunder or over-accommodat<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>consistent<strong>in</strong>formation and nurses fail<strong>in</strong>gto check parents’understand<strong>in</strong>g674 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 2. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of <strong>the</strong> Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Intervention Design/Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsKowalskiet al.(2006)Determ<strong>in</strong>e what sources andexpectations parents haveconcern<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation71 mo<strong>the</strong>rs and 30 fa<strong>the</strong>rs,ages 18-55<strong>Unit</strong>edStatesNone Qualitative questionnaire Parents received most<strong>in</strong>formation from nurse andexpectation was to receive<strong>in</strong>formation from <strong>the</strong>neonatologistLawhon(2002)Evaluation of an <strong>in</strong>dividualizednurs<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tervention based onparental/<strong>in</strong>fant competenceConvenience sample of 10<strong>in</strong>fants and <strong>the</strong>ir 10mo<strong>the</strong>rs/8 fa<strong>the</strong>rs ages 19-35 (median age 5 25.5years/26.5 years); (15 White,3Black)<strong>Unit</strong>edStatesIndividualized <strong>in</strong>tervention withnurses guid<strong>in</strong>g parentsthrough appraisal of <strong>in</strong>fant’sbehavior and appropriateresponsesQualitative. Enhanced parent/<strong>in</strong>fant competence wasmeasured with <strong>the</strong> Nurs<strong>in</strong>gChild Assessment Feed<strong>in</strong>gScale and <strong>the</strong> Assessment ofPreterm Infant Behavior at 3timesThe <strong>in</strong>tervention improvedparents’ ability to criticallyappraise <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant’s behaviorand to respond appropriatelyMaguireet al.(2007)Exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> e¡ects of a shortterm<strong>in</strong>tervention on parents’knowledge of <strong>in</strong>fantbehavioral cues and caregiv<strong>in</strong>g con¢dence10 sets of NICU parents,<strong>in</strong>fants o32 weeksgestation with noanomalies and notrequir<strong>in</strong>g surgeryTheNe<strong>the</strong>rlands4 sessions on preterm <strong>in</strong>fantbehavior over a 2 week period.Control group received no<strong>in</strong>structionsQuantitative trial. Lack ofCon¢dence <strong>in</strong> <strong>Care</strong> Giv<strong>in</strong>g andGlobal Con¢dence Scales.Questionnaire concern<strong>in</strong>gnurs<strong>in</strong>g support <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUNo signi¢cant di¡erences <strong>in</strong> caregiv<strong>in</strong>g con¢dence betweengroups. Intervention group hadsigni¢cantly higher nurs<strong>in</strong>gsupport scoresMelnyket al.(2001)Evaluate <strong>the</strong> e¡ectiveness of <strong>the</strong>creat<strong>in</strong>g opportunities forparent empowerment (COPE)program42 English speak<strong>in</strong>g mo<strong>the</strong>rs(18^38 years) of low birthweight, premature,hospitalized <strong>in</strong>fants; (64%White, 2.4% Hispanic)New York 4 sessions of (a) appearanceand behavior of preterm<strong>in</strong>fants and parent<strong>in</strong>gstrategies (b) workbook forparent activities to implementskills. Control group received 4sessions focused on hospitaland discharge proceduresPilot study, randomized cl<strong>in</strong>icaltrial. Infant mental developmentmeasured at 3 and 6 months.Mo<strong>the</strong>r’s anxiety, mood,stressors, social support,cop<strong>in</strong>g, and ability to feed<strong>in</strong>fantCOPE <strong>in</strong>fants had higher mentaldevelopment scores at 3 and 6months. COPE mo<strong>the</strong>rs hadless stress from sights andsounds of <strong>the</strong> NICU <strong>in</strong>itially andoverall stronger parent<strong>in</strong>gbeliefsJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 675

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>Table 2. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of <strong>the</strong> Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Intervention Design/Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsMelnyket al.(2006)Determ<strong>in</strong>e if <strong>the</strong> COPE<strong>in</strong>tervention could improve<strong>in</strong>fant behavioral anddevelopmental outcomes258 mo<strong>the</strong>rs/158 fa<strong>the</strong>rs/signi¢cant o<strong>the</strong>rs withpreterm <strong>in</strong>fants o2,500 g,26-34 weeks Englishspeak<strong>in</strong>g, 64%-77% White,83%-91% high schooleducation or greater. Meanparent age 5 28North East<strong>Unit</strong>edStates4 sessions on appearance andbehavioral characteristics ofpreterm <strong>in</strong>fants and parent<strong>in</strong>g;practice time for skills. Controlgroup received 4 sessions onhospital policies and servicesRandomized controlled trial.Parent anxiety, stress,depression, beliefs, <strong>in</strong>fantparent<strong>in</strong>teraction, and lengthof NICU and hospital stay. Dataafter <strong>in</strong>terventions,1 week. and2 months. after dischargeMo<strong>the</strong>rs (not fa<strong>the</strong>rs) reportedless stress <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU and lessdepression and anxiety at 2months Both parentsdemonstrated more positiveparent-<strong>in</strong>fant <strong>in</strong>teraction andbeliefs. COPE <strong>in</strong>fants had a 3.8day shorter NICU stayNottage(2005)Exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> relationshipbetween perceived socialsupport and parental use ofhospital non-medical supportservicesConvenience sample; 25mo<strong>the</strong>rs,19 fa<strong>the</strong>rs, ages24-54 years 75% White,23% African American,and 2% Lat<strong>in</strong>oEast coast<strong>Unit</strong>edStatesNone Quantitative; correlational.Perceived Social SupportScale for Family and Friends,and <strong>the</strong> Utilization of SocialSupport (created for this study)Nei<strong>the</strong>r perceived social supportfrom family nor friends wassigni¢cantly correlated withuse of hospital supportservicesPearsonandAnderson(2001)Evaluate <strong>the</strong> e¡ectiveness of aparent education <strong>in</strong>terventionon parent<strong>in</strong>g59 mo<strong>the</strong>rs, 45 fa<strong>the</strong>rs; 44NICU or special carenursery sta¡M<strong>in</strong>nesota Parent <strong>in</strong>tervention consist<strong>in</strong>g ofa facilitator and educationalsupportQuestionnaire focused oncontent and areas for futureprogram improvements. Sta¡survey of parental behaviorsAttend<strong>in</strong>g Parent’s Circle assistedparents to overcome obstacles<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU and <strong>in</strong>creasepositive parent<strong>in</strong>g behaviorsPetersonet al.(2004)Identify nurses’ perception andpractices of family-centeredcare (FCC)Convenience sample of 37NICU and 25 PICU nurses;54 were registered nurses,52% had 410 yearsexperience, 53% had aBachelor’s degree orhigherAcute carehospitalNone Quantitative. Family Centered<strong>Care</strong> Questionnaire (FCCQ)focused on both FCC necessityand current practiceThe number of nurses<strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g FCC <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>irpractice was signi¢cantly lowerthan those who stated it wasnecessary. Nurses with 410years experience practicedFCC less than thosewitho10 years. NICU nursespracticed FCC less than PICUnurses676 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 2. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of <strong>the</strong> Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Intervention Design/Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsSchroeder(1998)Exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> e¡ects of guidedlearn<strong>in</strong>g on mo<strong>the</strong>rs’ care of<strong>the</strong>ir premature <strong>in</strong>fant16 mo<strong>the</strong>rs of NICU <strong>in</strong>fants;ages 20-42; 12 White,1African American,1 Lat<strong>in</strong>a,1 Native American,1 AsianWiscons<strong>in</strong> Standardized parent learn<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>tervention focused on 6di¡erent aspects of guidedlearn<strong>in</strong>gMo<strong>the</strong>r’s Work<strong>in</strong>g Model ofPreterm Infant <strong>Care</strong>giv<strong>in</strong>g(Relationship) InterviewProtocol; RelationshipCompetencies Assessment;Parent Child Early RelationalAssessment rat<strong>in</strong>g scale;Family Provider RelationshipsInstrumentEngag<strong>in</strong>g with mo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> guidedparticipation can positively<strong>in</strong>£uence <strong>the</strong> relationshipbetween mo<strong>the</strong>r and <strong>in</strong>fantSchroederandPridham(2006)Determ<strong>in</strong>e if ‘‘guidedparticipation’’ improvesmo<strong>the</strong>rs’ relationshipcompetency with <strong>the</strong>ir NICUbabies16 mo<strong>the</strong>rs, 22-26 years, oflow birth weight <strong>in</strong>fant’s 28weeks gestational age orlessMidwest<strong>Unit</strong>edStatesMo<strong>the</strong>rs practiced parent<strong>in</strong>gthrough guided participationled by <strong>the</strong> research nurseRandomized trial. InternalWork<strong>in</strong>g Model of Relat<strong>in</strong>g to<strong>the</strong> Baby and <strong>the</strong> RelationshipCompetencies AssessmentMo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention grouphad higher relationshipcompetencies with <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fantthan mo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> controlgroupvan der Palet al.(2007)Compare <strong>the</strong> e¡ects of basic<strong>in</strong>fant developmental care and<strong>the</strong> Newborn IndividualizedDevelopmental <strong>Care</strong> andAssessment Program(NIDCAP) on parental stress,con¢dence, and perceivednurs<strong>in</strong>g support192 <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>in</strong> RCT 1 and 168 <strong>in</strong>RCT 2; all o32 weeksgestation, no anomalies ordrug addictionTheNe<strong>the</strong>rlandsBasic developmental care andNIDCAP2 consecutive randomized trials.Data collected us<strong>in</strong>g: <strong>the</strong>Cl<strong>in</strong>ical Risk Index for Babies,2 scales of <strong>the</strong> Mo<strong>the</strong>rs andBaby Scale, Nurse ParentSupport Tool, Parental StressorScale: NICUNo signi¢cant di¡erences werefound <strong>in</strong> parental stress,con¢dence, or perceivednurs<strong>in</strong>g supportWalker(1998)Identi¢cation of nurses’ views onbarriers to parent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>NICU298 NICU nurses Australia None 53-item questionnaire Nurses believed environmentalbarriers and parental attitudescontributed to parent<strong>in</strong>gdi⁄culties. Did not recognizethat nurs<strong>in</strong>g practices and unitprotocols could be barriersJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 677

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>Table 2. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of <strong>the</strong> Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Intervention Design/Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsWielengaet al.(2006)Determ<strong>in</strong>e if provid<strong>in</strong>g careaccord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> NewbornIndividualized Developmental<strong>Care</strong> and AssessmentProgram (NIDCAP) pr<strong>in</strong>cipalswould <strong>in</strong>crease parentsatisfaction50 parents age 516-40years, (25 <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention/25<strong>in</strong> control group) of <strong>in</strong>fants30 weeks gestation or less;English or Dutch speak<strong>in</strong>g.No <strong>in</strong>fant anomaliesTheNe<strong>the</strong>rlandsNIDCAP <strong>in</strong>terventions areguided by <strong>in</strong>fant’s response,developmental level, andphysical condition. Familycentered with goal ofempower<strong>in</strong>g parents to bemembers of healthcare teamQuasi-experimental. Controlgroup received traditional care,<strong>in</strong>terventional group receivedcare guided by NIDCAP.Outcomes measured by <strong>the</strong>NICU Parent Satisfaction Formand Nurse Parent Support ToolParents were signi¢cantly moresatis¢ed with care provided byNIDCAP pr<strong>in</strong>ciplesMixed MethodBruns andMcCollum(2002)Exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> perspectives ofmo<strong>the</strong>rs, nurses, andneonatologists concern<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> importance andimplementation of caregiv<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>in</strong>formation exchange, andrelationships <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> context offamily centered care55 mo<strong>the</strong>rs 18-42 years 75%Anglo and married.18neonatologists, and 123nurses; mostly female andAngloMidwestern<strong>Unit</strong>edStatesNone PARTNERS questionnaire.Qualitative content analysisMo<strong>the</strong>rs and nurses had higherrat<strong>in</strong>gs than neonatologists onimplementation of caregiv<strong>in</strong>g.Mo<strong>the</strong>rs and nurses ratedimportance higher thanimplementation for <strong>in</strong>formationexchange and relationshipsMacnabet al.(1998)To assess <strong>the</strong> potential forpromot<strong>in</strong>g journal writ<strong>in</strong>g forparents receiv<strong>in</strong>g socialsupport <strong>in</strong> a special carenursery73 parents, English as aprimary language,m<strong>in</strong>imum of a 12th gradeeducationBritishColumbiaAn <strong>in</strong>structional pamphlet onjournal writ<strong>in</strong>g was provided to<strong>the</strong> participantsFollow-up phone <strong>in</strong>terview 6weeks after enrollment todeterm<strong>in</strong>e if a journal was kept32%of parents kept a journal,73% of <strong>the</strong>se felt it helpedreduce stress. The #1 journalentry topic was see<strong>in</strong>g yourchild attached to mach<strong>in</strong>esfollowed by <strong>in</strong>teractions withnurs<strong>in</strong>g sta¡QualitativeBuarqueet al.(2006)Investigate <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>£uence ofsupport groups on families ofat-risk newborns and on NICUsta¡13 mo<strong>the</strong>rs, 6 fa<strong>the</strong>rs, 2grandmo<strong>the</strong>rs, and 16 sta¡membersBrazil None Observation of support groupmeet<strong>in</strong>gs and open-ended<strong>in</strong>terviewsSupport groups provided familieswith <strong>in</strong>formation, emotionalsupport and strength. Parentto-parentsupport wasessential678 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 2. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of <strong>the</strong> Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Intervention Design/Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsCescutti-Butler andGalv<strong>in</strong>(2003)Explore and describe parents’perception of sta¡competencies <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU8 parents South-westEnglandNone Grounded <strong>the</strong>ory. Unstructured<strong>in</strong>terview.Parent perception of competencywas based more on car<strong>in</strong>gbehaviors than skills. Parentswanted (a) to be <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to<strong>the</strong> NICU, (b) control, (c) achoice to stay dur<strong>in</strong>gprocedures, and (d)communication with <strong>the</strong>healthcare team andappropriate <strong>in</strong>formationWigert et al.(2008)Explore conditions for parentparticipation <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant care <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> NICU10 parents,14 nurses and 15managersSweden None Observations and <strong>in</strong>terviews withrepresentatives from sta¡,management, and parentsConditions for parentparticipation were driven by<strong>the</strong> sta¡, budgetaryconstra<strong>in</strong>ts and unit rout<strong>in</strong>esJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 679

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>A ‘‘power struggle’’ between <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fant’s nurse and mo<strong>the</strong>roften occurred.Mo<strong>the</strong>rs felt that provid<strong>in</strong>g breast milk was a methodfor establish<strong>in</strong>g a relationship and a connectionto <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants (Lupton & Fenwick).Lupton and Fenwick (2001) discovered that <strong>in</strong> somecases nurses were found to <strong>in</strong>appropriately limit <strong>the</strong>parent’s contact with <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants. They reported an<strong>in</strong>cident where <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r of a stable, 34 week gestation<strong>in</strong>fant asked <strong>the</strong> nurse if she could hold her<strong>in</strong>fant and was told, ‘‘No, you’ve had your cuddle today’’(p. 1016). Mo<strong>the</strong>rs also reported that whenarriv<strong>in</strong>g on time to provide care for <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant, <strong>the</strong>ywere sometimes <strong>in</strong>formed by <strong>the</strong> nurse that <strong>the</strong> carehad already been adm<strong>in</strong>istered. Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> study,<strong>the</strong>re were additional claims of several mo<strong>the</strong>rs arriv<strong>in</strong>gto <strong>the</strong> nursery to visit <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants and be<strong>in</strong>gtold ‘‘bluntly and loudly’’ (p. 1017) that <strong>the</strong> nurserywas closed. Some nurses stated <strong>the</strong>y felt as though<strong>the</strong>y were personally responsible for how <strong>the</strong> parentsparented, and <strong>the</strong>y took <strong>the</strong>ir role as teachersvery seriously. As a result, mo<strong>the</strong>rs claimed thatnurses often hovered over <strong>the</strong>m and warned ofoverhandl<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fants. These actions resulted<strong>in</strong> feel<strong>in</strong>gs of anger and frustration on <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r’spart.A Need to be Positively Perceived by <strong>the</strong> NurserySta¡Mo<strong>the</strong>rs of NICU <strong>in</strong>fants desired to be perceivedpositively by <strong>the</strong> nursery sta¡ (Fenwick et al.,2001a, 2002). They feared that voic<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>ir op<strong>in</strong>ionwould <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant’s vulnerability. Threestudies described <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r’s fear of becom<strong>in</strong>glabeled by <strong>the</strong> nurses as ‘‘di⁄cult’’ (Hurst, 2001a,2001b; Lupton & Fenwick, 2001). They were concernedabout be<strong>in</strong>g seen as pushy and felt <strong>the</strong>yneeded to be ‘‘nice’’ to <strong>the</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g sta¡ to facilitatea good relationship (Fenwick et al., 2002). They alsofelt <strong>the</strong>y needed to conform to <strong>the</strong> ‘‘good mo<strong>the</strong>r’’role as constructed by <strong>the</strong> nurses. The nurses admittedto hav<strong>in</strong>g speci¢c criteria for who quali¢edas <strong>the</strong> ‘‘good mo<strong>the</strong>r.’’ These women ‘‘asked lots ofquestions, appeared eager to learn everyth<strong>in</strong>g,and could be reasoned with’’ (Lupton & Fenwick,p. 1018).Mo<strong>the</strong>rs withheld or guarded feel<strong>in</strong>gs for fear of los<strong>in</strong>gaccess to <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant. Fenwick et al. (2001a)discovered that fa<strong>the</strong>rs were often <strong>the</strong> ones to <strong>in</strong>itiateany compla<strong>in</strong>ts about nurs<strong>in</strong>g sta¡, andmo<strong>the</strong>rs seemed to rely on this. Con£icts between<strong>the</strong> nurse and <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r were rarely resolved, andgenerally <strong>the</strong> nurse would discont<strong>in</strong>ue car<strong>in</strong>g forthat <strong>in</strong>fant and a di¡erent nurse would be assigned.Mo<strong>the</strong>rs who were labeled ‘‘troublemakers’’ oftendiscovered that <strong>the</strong> outcome was passive-aggressivebehaviors from <strong>the</strong> nurses. If <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r-nurserelationship could not be negotiated, mo<strong>the</strong>rs became‘‘disenfranchised,’’ which fur<strong>the</strong>r contributedto <strong>the</strong>ir stress levels, and <strong>the</strong>se women respondedby distanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong>mselves. These researchers concludedthat this model of care was traditionallycentered on <strong>the</strong> provider and not <strong>the</strong> family.A Need for Individualized <strong>Care</strong>While <strong>the</strong> need to receive <strong>in</strong>dividualized care mayseem obvious, researchers suggest that this needmay be overlooked <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU (Hurst, 2001b; Punthmatharith,Buddharat, & Kamlangdee, 2007;Wielenga, Smit, & Unk, 2006). This is most apparentwhen address<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> needs of fa<strong>the</strong>rs. Of <strong>the</strong> 60studies reviewed for this paper, 23 <strong>in</strong>cluded fa<strong>the</strong>rs<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir sample; however, <strong>the</strong> number of mo<strong>the</strong>rsand fa<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> each study were not typically equal(Alderson et al., 2006; Arockiasamy et al., 2008;Buarque, de Carvalho Lima, Parry Scott, &Vasconcelos, 2006; Denney, 2003; Gardner et al.,2002; Herbst & Maree, 2006; Higg<strong>in</strong>s & Dullow,2003; Jamsa & Jamsa,1998; Jones, Woodhouse, &Rowe, 2007; Joseph et al., 2007; Kowalski, Leef,Mackley, Spear, & Paul, 2006; Lam et al., 2007; Lawhon,2002; Lee, Lee, Rank<strong>in</strong>, Alkon, & Weiss, 2003;L<strong>in</strong>dberg, Axelsson, & Ohrl<strong>in</strong>g, 2007; Macguire,Bruil, Wit, & Walhter, 2007; Melnyk et al., 2006; Nottage,2005; Pearson & Anderson, 2001; P<strong>in</strong>elli, 2000;Pohlman, 2005; Taylor-Huber, 1998; Ward, 2001). Inone of <strong>the</strong>se studies, researchers found that <strong>the</strong>needs of mo<strong>the</strong>rs and fa<strong>the</strong>rs were di¡erent.In <strong>the</strong>ir study of an <strong>in</strong>tervention to improve mentalhealth outcomes <strong>in</strong> parents with <strong>in</strong>fants <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU,Melnyk et al. (2006) found that <strong>the</strong> response ofmo<strong>the</strong>rs and fa<strong>the</strong>rs to <strong>in</strong>terventions was not <strong>the</strong>same. After implementation of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>tervention, <strong>the</strong>yfound that <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> research group hadless anxiety and stronger parental beliefs. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly,<strong>the</strong>y found no di¡erence <strong>in</strong> stress level <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>fa<strong>the</strong>rs and no di¡erence <strong>in</strong> state anxiety and depressivesymptoms at 2 months postdischarge. Theauthors concluded that <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>rs needed to befollowed for a longer period of time (Melnyk et al.).Ward (2001) also found di¡erences <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> needs ofmo<strong>the</strong>rs and fa<strong>the</strong>rs. She discovered that whileboth thought assurance needs were most importantand support needs were least important, <strong>the</strong>680 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 3: <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Needs and Support <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUStudy andYear Purpose of Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsQuantitativeDenney(2003)Measure <strong>the</strong> occurrence of stress <strong>in</strong>Lat<strong>in</strong>o NICU parents and <strong>the</strong>relation of parental stress, nurs<strong>in</strong>gsupport, and parent<strong>in</strong>g e⁄cacy32 Lat<strong>in</strong>a mo<strong>the</strong>rs and 16fa<strong>the</strong>rs, mean age 5 29yearsSou<strong>the</strong>rnCaliforniaParental Stressor Scale:NICU, <strong>the</strong> NICU<strong>Care</strong>giv<strong>in</strong>g and Communication Scale, <strong>the</strong>Nurse Parent Support Tool, Maternal E⁄cacyQuestionnaire, and Family DemographicQuestionnaire<strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> stress was not signi¢cantly related toparent<strong>in</strong>g e⁄cacy. <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> e⁄cacy wassigni¢cantly related to nurs<strong>in</strong>g support.Sources of stress were di¡erent for Lat<strong>in</strong>aparents than previous studies with WhiteparentsGardneret al.(2002)Investigate <strong>the</strong> experiences ofparents <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU to design afamily support programRetrospective purposivesampl<strong>in</strong>g of parents with<strong>in</strong>fants discharged <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>past year.119 participants(114 mo<strong>the</strong>rs, 5 fa<strong>the</strong>rs)Regionaltertiaryreferral center39 item questionnaire designed for this study.250 questionnaires sent out by mail with a48% response rateParents were satis¢ed with <strong>the</strong>ir care but desiredto do more hands on care of <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fant.Parents wanted a more active role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>decision to discharge <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>in</strong>fantLee et al.(2003)Describe <strong>the</strong> stressful events ofCh<strong>in</strong>ese American NICU parentsand assess <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>£uence ofacculturation, parentcharacteristic, and social supportson parent stress30 Ch<strong>in</strong>ese American families(30 mo<strong>the</strong>rs, 25 fa<strong>the</strong>rs) 18-43 yearsSan Francisco Infant health data from <strong>the</strong> medical record,Parental Stressor Scale: InfantHospitalization, Su<strong>in</strong>n-Lew Asian Self-IdentityAcculturation Scale, Family Support ScaleThe comb<strong>in</strong>ed e¡ects of uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty about <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>fant’s condition and future, a strong belief <strong>in</strong>Asian family values, and lack of support fromhealth care providers accounted for 26% of<strong>the</strong> variance <strong>in</strong> parental stress for mo<strong>the</strong>rs and55% for fa<strong>the</strong>rsMok andLeung(2006)Explore <strong>the</strong> supportive behaviors ofnurses <strong>in</strong> a Hong Kong NICU37 NICU mo<strong>the</strong>rs; 26-38 yearsoldHong Kong Nurses Parent Support Tool Mo<strong>the</strong>rs rated nurs<strong>in</strong>g support as highlyimportant. Parents desired more nurs<strong>in</strong>gsupport than <strong>the</strong>y received <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> area of<strong>in</strong>formation shar<strong>in</strong>g and supportivecommunicationJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 681

I N R EVIEW <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Neonatal</strong> <strong>Intensive</strong> <strong>Care</strong> <strong>Unit</strong>Table 3. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsP<strong>in</strong>elli(2000)Determ<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> relationship betweenfamily cop<strong>in</strong>g and resources andfamily adjustment and parentalstress <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU124 couples, mean age 5 31years mo<strong>the</strong>rs/32 yearsfa<strong>the</strong>rsOntaria,CanadaBased o n <strong>the</strong> Resiliency Model of Family Stress,Adjustment, and Adaptation. Instruments<strong>in</strong>cluded: State Anxiety Scale, FamilyInventory of Resources for Management,Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluationscale, and <strong>the</strong> McMaster Family AssessmentDeviceResources were more strongly correlated withpositive adjustment and decreased stressthan cop<strong>in</strong>g or be<strong>in</strong>g a ¢rst time parent.F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs were similar between mo<strong>the</strong>rs andfa<strong>the</strong>rs; however, mo<strong>the</strong>rs used more cop<strong>in</strong>gstrategies than fa<strong>the</strong>rsVanRiper(2001)Describe maternal perceptionsabout family provider relationshipsand <strong>the</strong> correlation with familywell-be<strong>in</strong>g55 NICU mo<strong>the</strong>rs; 69% White,29% African American,and 2% Lat<strong>in</strong>o; meanage 5 29 range 17-40 yearsMidwestern<strong>Unit</strong>ed StatesFamily Provider Relationships Instrument-NICU,18 item version of Ry¡’s measure ofpsychological well-be<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>the</strong> GeneralScale of <strong>the</strong> Family Assessment MeasureMo<strong>the</strong>rs had greater family satisfaction and weremore satis¢ed with <strong>the</strong>ir care and reportedgreater psychological well-be<strong>in</strong>g when <strong>the</strong>yviewed <strong>the</strong>ir provider relationship as positiveQualitativeAldersonet al.(2006)Explore <strong>the</strong> views of parents and sta¡concern<strong>in</strong>g shar<strong>in</strong>g of knowledgeand care of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>fantParents of 80 NICU <strong>in</strong>fantswith con¢rmed or potentialneurological problems. Allmo<strong>the</strong>rs participated,16fa<strong>the</strong>rs and 40 senior sta¡Sou<strong>the</strong>rnEnglandObservations over an 18 month period; semistructured<strong>in</strong>terviewsParents described <strong>the</strong>ir views on two-waydecision mak<strong>in</strong>g and a practical need to know.Physicians preferred a distanc<strong>in</strong>g aspect of<strong>in</strong>formed consent. Parents preferred ‘‘draw<strong>in</strong>gtoge<strong>the</strong>r’’Fenwicket al.(2001a)Describe and expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> experienceof mo<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICU from <strong>the</strong>woman’s po<strong>in</strong>t of view28 mostly Australian bornwomen 19-41 years and 20nursesAustralia Mo<strong>the</strong>rs <strong>in</strong>terviewed prior to <strong>in</strong>fant dischargeand 8-12 weeks after. Interviews with 20nurses, <strong>in</strong>formal conversations with parents,and bedside nurse/parent <strong>in</strong>teractionsInhibitive or authoritative styles of nurs<strong>in</strong>g careled to <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>rs’ feel<strong>in</strong>gs of struggl<strong>in</strong>g tomo<strong>the</strong>r, feel<strong>in</strong>g disa¡ected, guard<strong>in</strong>g offeel<strong>in</strong>gs, attempts to speak up and out, fear ofearn<strong>in</strong>g a reputation or recrim<strong>in</strong>ation, and¢nally a disenfranchised mo<strong>the</strong>r682 JOGNN, 37, 666-691; 2008. DOI: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00288.x http://jognn.awhonn.org

Cleveland, L. M. I N R EVIEWTable 3. Cont<strong>in</strong>uedStudy andYear Purpose of Study Participants Sett<strong>in</strong>g Methods Major F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsFenwicket al.(2001b)Explore <strong>the</strong> use of ‘‘chat’’ as a methodof establish<strong>in</strong>g family-centeredcare <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> NICUSame data base as Fenwicket al. 2001aAustralia Same as Fenwick et al. 2001a The use of ‘‘chat’’ or an <strong>in</strong>formal communicationstyle between parents and nurses wasidenti¢ed as critical to <strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>rs. Only 12%of <strong>the</strong> bedside record<strong>in</strong>gs revealed <strong>the</strong> nurses’use of this technique.Fenwicket al.(2002)Ga<strong>in</strong> an understand<strong>in</strong>g of howwomen perceive early mo<strong>the</strong>r<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> NICUSame data base as Fenwicket al. 2001aAustralia Same as Fenwick et al. 2001a The category ‘‘learn<strong>in</strong>g and play<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> game’’was accomplished through: ‘‘suss<strong>in</strong>g’’ th<strong>in</strong>gsout (identify<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> groundrules), be<strong>in</strong>g nice, and prov<strong>in</strong>g one’scapabilitiesHerbst andMaree(2006)Describe parents’ needs andrecommendations forempowerment from <strong>the</strong>irperspective20 Master’s prepared nurses South Africa Parent focus groups. Data were presented tonurses with discussion of solutions to meet<strong>the</strong>se needsTen empowerment guidel<strong>in</strong>es were suggestedby <strong>the</strong> nurs<strong>in</strong>g focus groupL<strong>in</strong>dberget al.(2007)Describe <strong>the</strong> fa<strong>the</strong>r’s perspective ofhav<strong>in</strong>g a premature <strong>in</strong>fant8 fa<strong>the</strong>rs of premature <strong>in</strong>fants Nor<strong>the</strong>rnSwedenNarrative <strong>in</strong>terviews Three <strong>the</strong>mes were identi¢ed: suddenly be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>a situation never re£ected on, putt<strong>in</strong>g mo<strong>the</strong>rand <strong>in</strong>fant ¢rst, and need<strong>in</strong>g to be understoodLubbe(2005)Develop an <strong>in</strong>tervention careprogram for NICU parentsAll parents with an <strong>in</strong>fant <strong>in</strong>one of <strong>the</strong> two selectedNICUsSouth Africa Open-ended questions <strong>Parent<strong>in</strong>g</strong> needs <strong>in</strong>cluded: <strong>in</strong>formation,emotional support, communication, learn<strong>in</strong>g,and preparation for discharge. The EarlyIntervention <strong>Care</strong> Progamme was <strong>the</strong>ndesigned to meet <strong>the</strong>se needsJOGNN 2008; Vol. 37, Issue 6 683