Today

KCW-dec_jan-2015_6-amended-final

KCW-dec_jan-2015_6-amended-final

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

58 December/January April/May 2011 2015/16 Kensington, Chelsea & Westminster <strong>Today</strong> www.KCW<strong>Today</strong>.co.uk 020 7738 2348<br />

December/January 2015/16<br />

Kensington, Chelsea & Westminster <strong>Today</strong><br />

59<br />

Arts & Culture<br />

Arts & Culture<br />

online: www.KCW<strong>Today</strong>.co.uk<br />

Photograph © Sophie Winham<br />

Bernard Cohen:<br />

About Now<br />

By Ian McKay<br />

Flowers Gallery<br />

ISBN 978-1-906412-71-5<br />

92pp. £30<br />

I<br />

have always been a bit wary of<br />

the word ‘zany’ - it conjures up<br />

amusingly unconventional and<br />

idiosyncratic humour, and derives from<br />

a clownish character in Commedia<br />

dell’arte, Zanni. Cohen states that he<br />

struggles with the titles of his paintings,<br />

and yet has named four Zany at Home,<br />

Zany in Grey, Zany Again and Zany in<br />

the Detail, which, apart from the lack of<br />

humour, are certainly unconventional<br />

and idiosyncratic. Complex swirling<br />

shapes, overlapping colours, geometric<br />

lines, rectangles and circles, squiggles,<br />

all meticulously laid in acrylic or oil<br />

on canvas or linen, using masking tape<br />

to achieve the overlaying effects, some<br />

like a smashed Victorian mosaic tiled<br />

floor, others like those 3D stereogram<br />

images, where one’s eyes have to go ‘lazy’<br />

to see the hidden picture within. David<br />

Hockney said, when trying to paint<br />

swimming pools in California, he was<br />

influenced not only by Dubuffet, but by<br />

Cohen’s ‘Spaghetti Paintings’. In some<br />

later works textures and stencilled and<br />

painted shapes, are enmeshed in layers<br />

of patterns and motifs, like aeroplanes,<br />

to produce a dizzying assault on the<br />

senses. He titled several paintings after<br />

Billy Wilder’s Cold War comedy One,<br />

Two, Three, starring James Cagney as a<br />

Coca Cola executive in West Berlin, but,<br />

for some inexplicable reason, called the<br />

series One, Two, Three, Four, and there<br />

are no clues in the works as to what they<br />

have to do with this funny, rapid-fire<br />

satire.<br />

The academic and critic Ian McKay<br />

has written what amounts to a treatise<br />

on Cohen, and intellectualises on the<br />

meaning behind his work, citing T.S.<br />

Eliot, Samuel Beckett, Jean-Paul Sartre,<br />

Albert Camus and existentialism, Henri<br />

Bergson, Thomas Hardy, even Joseph<br />

Conrad. But are his paintings that<br />

complicated and imbued with deep and<br />

hidden meanings? McKay was minded<br />

to ask Cohen whether he had painted a<br />

self-portrait, but found the question no<br />

longer relevant, as he now reckons that<br />

his paintings are all self-portraits. Well,<br />

call me old-fashioned, but I just don’t<br />

buy that. He is patently obsessed with<br />

his subject, even re-reading those novels<br />

that Cohen has been reading; works by<br />

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Philip Roth, and<br />

Donna Tartt, concluding that what they<br />

all have in common is “secrets that define<br />

the human being”.<br />

Cohen trained at St Martin’s, then<br />

the Slade, in the 1950s, returning in<br />

1988 to become Chair, Professor, and<br />

Director of Slade School of Fine Art, a<br />

post he held for 12 years. His first solo<br />

exhibition was at Gimpel Fils in 1958,<br />

and since then he has had one-man<br />

shows at Kasmin, Waddington, and, of<br />

course, Flowers East, West and Central,<br />

a Retrospective at the Hayward in 1972,<br />

and 48 of the works of this important<br />

British abstract expressionist painter are<br />

held by Tate, but none from the 2000-<br />

2015 period covered in this book.<br />

Don Grant<br />

They All Love<br />

Jack: Busting the<br />

Ripper<br />

By Bruce Robinson<br />

Harper<br />

ISBN-10: 006229637X<br />

They All Love Jack is Bruce Robinson’s<br />

800 page doorstop of an attempt to<br />

figure out what has baffled many: just<br />

who murdered (at least) five women<br />

in 1888? Who was Jack the Ripper?<br />

It started out as a £15 pub bet that<br />

Robinson couldn’t solve the mystery,<br />

made over a decade ago, but it is easy to<br />

see that it developed into an obsession.<br />

Robinson’s writing is personal,<br />

engaging, and scathing; however his<br />

gonzo-esque style means that he has a<br />

tendency to ramble and sometimes the<br />

direction of the dialogue will abruptly<br />

lurch. A chapter focused on discussing a<br />

particular murder will end up containing<br />

a rant about the immorality of the<br />

Victorians and a handful of paragraphs,<br />

seemingly out of place, on Freemason<br />

archaeology.<br />

One really has to jump on Robinson’s<br />

train of thought and hold on, as he<br />

obviously considers all these things<br />

relevant and in their proper place,<br />

which, given that this is an argument<br />

being made in support of a theory<br />

and not fiction, means that it must<br />

make sense to him, at least. And the<br />

immorality of the Victorians and<br />

Freemasonry are the heart Robinson’s<br />

case, the target of his thrusts, joined<br />

on the chopping block with the rest of<br />

Ripperology.<br />

It’s almost a shame that he felt<br />

the need to try to solve the case.<br />

As a criticism of an attack upon<br />

the Victorians, the related culture<br />

of Freemasonry, and self-declared<br />

Ripperologists, the text is powerful and<br />

merciless.<br />

Robinson’s problem is that of many<br />

conspiracy theorists; that just because<br />

your argument makes sense doesn’t<br />

mean it’s right. Robinson constructs<br />

the theoretical framework within which<br />

his argument runs smoothly, however<br />

it comes short of persuading that this<br />

is what actually happened: There is a<br />

difference between what could have<br />

happened and what did, what makes<br />

sense and what is.<br />

Robinson’s attempt to solve<br />

the case is a shame, not because it<br />

is unconvincing, but because it is,<br />

obviously, the point of this behemoth.<br />

Had it simply been a few hundred pages<br />

titled Why I hate the Victorians, and why<br />

you should too, then it would have been<br />

far more tolerable to read; as it stands, it<br />

is a task.<br />

Approach it as a rational argument,<br />

and Robinson’s writing style may quickly<br />

obscure a clean reading; approach it as a<br />

quirky text with a sharp edge, something<br />

a little risqué, and all the Ripper stuff<br />

gets in the way. Which, unfortunately,<br />

leaves it somewhat unapproachable.<br />

Fergus Coltsmann<br />

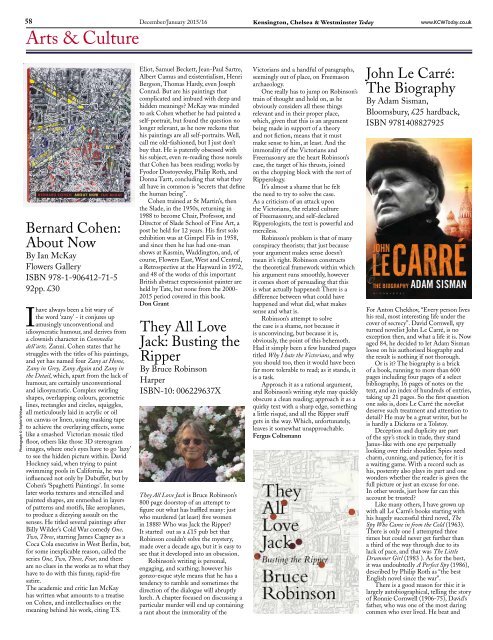

John Le Carré:<br />

The Biography<br />

By Adam Sisman,<br />

Bloomsbury, £25 hardback,<br />

ISBN 9781408827925<br />

For Anton Chekhov, “Every person lives<br />

his real, most interesting life under the<br />

cover of secrecy”. David Cornwell, spy<br />

turned novelist John Le Carré, is no<br />

exception then, and what a life it is. Now<br />

aged 84, he decided to let Adam Sisman<br />

loose on his authorised biography and<br />

the result is nothing if not thorough.<br />

Or is it? The biography is a brick<br />

of a book, running to more than 600<br />

pages including four pages of a select<br />

bibliography, 16 pages of notes on the<br />

text, and an index of hundreds of entries,<br />

taking up 21 pages. So the first question<br />

one asks is, does Le Carré the novelist<br />

deserve such treatment and attention to<br />

detail? He may be a great writer, but he<br />

is hardly a Dickens or a Tolstoy.<br />

Deception and duplicity are part<br />

of the spy’s stock in trade, they stand<br />

Janus-like with one eye perpetually<br />

looking over their shoulder. Spies need<br />

charm, cunning, and patience, for it is<br />

a waiting game. With a record such as<br />

his, posterity also plays its part and one<br />

wonders whether the reader is given the<br />

full picture or just an excuse for one.<br />

In other words, just how far can this<br />

account be trusted?<br />

Like many others, I have grown up<br />

with all Le Carré’s books starting with<br />

his hugely successful third novel, The<br />

Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963).<br />

There is only one I attempted three<br />

times but could never get further than<br />

a third of the way through due to its<br />

lack of pace, and that was The Little<br />

Drummer Girl (1983 ). As for the best,<br />

it was undoubtedly A Perfect Spy (1986),<br />

described by Philip Roth as “the best<br />

English novel since the war”.<br />

There is a good reason for this: it is<br />

largely autobiographical, telling the story<br />

of Ronnie Cornwell (1906-75), David’s<br />

father, who was one of the most daring<br />

conmen who ever lived. He beat and<br />

sexually abused his boys, and beat his<br />

women (his wife did a runner when the<br />

younger brother was aged five), lived the<br />

high life but ran away from his bills, and<br />

served two jail terms. No wonder young<br />

David had insecurities which were never<br />

going to go away.<br />

We read of Cornwell’s spying on<br />

friends and tipping off MI5 about<br />

their leftward-leanings; so loyalty to<br />

his country came first, not them. After<br />

studying modern languages at Oxford,<br />

he switched his allegiance to MI6, and<br />

then taught at Eton for a while. Once he<br />

had made his first £20,000, in 1964, he<br />

jacked it all in for full-time writing and<br />

made a number of fortunes through book<br />

sales and film and television rights.<br />

He claims to be a lifelong Labour<br />

voter. He will not allow his publishers to<br />

enter his books for literary competitions,<br />

such as the Man Booker. And he<br />

has turned down gongs, including a<br />

knighthood. Is this because of humility,<br />

or vanity? His first marriage ended in<br />

failure and he had a string of affairs,<br />

including with the wife of a best friend.<br />

He once contemplated suicide. Indeed<br />

he comes across as not a very pleasant<br />

character at all, so one wonders why he<br />

supported this publication, and why now.<br />

If one has a private inroad to certain<br />

characters he encountered in real life,<br />

but for some reason did not make it onto<br />

the page, one can apply a different sort<br />

of test. For example, there is no mention<br />

of Czech President Vaclav Havel, or his<br />

biographer Michael Zantovsky, recently<br />

Czech ambassador to London. There is<br />

no mention of Nick Scarf, also an MI5<br />

and MI6 man who, he claimed, was Le<br />

Carré’s inspiration for Barley Blair in The<br />

Russia House (1989). Never considered,<br />

or edited out?<br />

There are some who argue, of course,<br />

that definitive biographies can only be<br />

written after the death of their subject.<br />

This is hinted at, and one wonders what<br />

new revelations are to come. And he has<br />

promised his own memoir in maybe a<br />

year’s time. Unfinished business?<br />

And Le Carré has his critics as well<br />

as his admirers: Salman Rushdie, the<br />

late Christopher Hitchens, and Clive<br />

James among them. One of James’s<br />

many autobiographical books is entitled<br />

Unreliable Memoirs and one wonders<br />

whether this may apply too to Cornwell/<br />

Le Carré?<br />

So, even after more than 600 pages,<br />

the man remains enigmatic to the end,<br />

and therefore what is embarked upon<br />

as a quest for the truth is ultimately<br />

unsatisfying.<br />

Or maybe he gave the game away<br />

not in this book, but in a quotation<br />

used in Ben Macintyre’s book, A Spy<br />

Among Friends (2014). On page 245,<br />

Le Carré states: The privately educated<br />

Englishman “is the greatest dissembler<br />

on earth… Nobody will charm you so<br />

glibly, disguise his feelings from you<br />

better, cover his tracks more skilfully, or<br />

find it harder to confess to you that he<br />

has been a damn fool…<br />

“He can have a Force Twelve nervous<br />

breakdown while he stands next to you<br />

in the bus queue and you may be his best<br />

friend but you’ll never be the wiser.”<br />

After 600 pages, and £25, wiser is<br />

exactly what you should be.<br />

James Pallas<br />

Fallout 4<br />

By Fergus Coltsman<br />

My first few hours experience of Fallout<br />

4 were not of playing it, but of upgrading<br />

my PC in order to actually run and<br />

download all 24 glorious gigabytes of<br />

it. This is a good thing, both that the<br />

minimum specs for the PC version<br />

recommend an obscene 8 gigs of RAM<br />

and that it took an hour to download, it<br />

illustrates in raw numbers the behemoth<br />

of a game it is.<br />

(Spoiler warning: This article will<br />

contain incredibly minor spoilers for the<br />

first two hours or so of plot.)<br />

Fallout 4 starts you out in prenuclear<br />

apocalypse Boston, 2077, just<br />

as the US/China cold war turns hot<br />

and you’re rushed into the nearest<br />

bomb shelter. Things quickly take a<br />

turn for the sinister and 200 years later<br />

you stumble out, into the irradiated<br />

wasteland Massachusetts has become.<br />

This scene setting doesn’t take very<br />

long, which is a shame. Fallout 3 forced<br />

you spend a couple hours in the sterile,<br />

claustrophobic shelter before thrusting<br />

you wide eyed into the hellish nightmare<br />

of the outside world, inspiring the sort<br />

of joyous fear that only comes with<br />

freedom. In contrast, F4 rushes you,<br />

lacking the emotional punch of 3.<br />

But what it’s rushing you toward is<br />

good. Bethesda, the game’s developers,<br />

have never been Shakespearean writers,<br />

but they have always been fantastically<br />

immersive world builders, and Boston is<br />

no exception. Exploring long abandoned<br />

towns in the morning sun, hunting<br />

mutated wildlife in grey-green fogged<br />

hills, and fighting running battles with<br />

psychotic raiders in tight city streets as<br />

thunder and lightning cracks overhead<br />

all bring the world alive.<br />

Further life is added by the colourful<br />

cast of survivors eking out life in the<br />

wastes. From wandering tradesmen to<br />

almost-thriving towns growing inside<br />

a baseball stadium, the characters are<br />

lively and diverse, (if one can get past<br />

the Boston accent). F4 offers a new<br />

way to interact with them; previously,<br />

aside from the odd grunt or Thu’um,<br />

Bethesda player characters were silent,<br />

F4 has a Mass Effect-esque dialogue<br />

system, where conversing characters<br />

actually have an immersive back and<br />

forth; an actual dialogue. It doesn’t even<br />

suffer too badly from the problem that<br />

plagued ME, where the short prompt in<br />

the options menu would not intuitively<br />

relate to what your character ended up<br />

saying. That said, very occasionally the<br />

characters will fall into the Uncanny<br />

Valley and throw the immersion off.<br />

The overall gameplay is stronger than<br />

previous games, F4 is actually a good<br />

shooter rather than a tolerable one.<br />

Enemies will dynamically duck in and<br />

out of cover, your guns kick and click<br />

satisfactorily, and bad guys stagger in<br />

response to hits, often accompanied by<br />

a visceral spray of blood; and ghouls and<br />

other baddies visibly disintegrate as they<br />

take damage.<br />

The depth of customisation has<br />

reached new heights. Characters can<br />

be customised to ridiculous degrees,<br />

weapons can be molded to the point of<br />

being unrecognisable from their original,<br />

settlements can be built and improved<br />

to protect their occupants. The overall<br />

effect is that not only is your character<br />

and adventure unique, but your Boston<br />

will be unique to you as well.<br />

At time of writing, I’m only twenty<br />

hours in, which is barely a scratch<br />

on the surface, with much left to be<br />

explored. Given the substantial engine<br />

improvements over Skyrim, I don’t even<br />

feel like I’ve figured out the fundamental<br />

P E T A L<br />

PAINTING AND EVERYTHING ELSE<br />

JULIA WHATLEY supports PETAL ‘Painting and Everything Else’, a charity<br />

which encourages creative attitudes and thinking from an early age and<br />

sponsors creativity in children.<br />

The emphasis is on childrens’ development. Julia says “When a child is<br />

traumatised they need love and support to help them go forwards in life,<br />

and creativity can help unlock the trauma”<br />

Everything about Julia is to promote positivity in others, especially<br />

children. She devotes her time to creating works of art. She says,<br />

“Anything I have produced in the last 12 years is for the positive to<br />

outweigh and replace the negative”.<br />

Her work, is like her personality; overwhelmingly sensitive, colourful<br />

and positive. The ideas, themes are poignant and powerful. Her desire is<br />

to enable people to express their true selves in a an unhindered free way<br />

and to create world peace<br />

Anyone wishing to get involved in the charity should contact www.<br />

talismanlondon.com jamesnalty@gmail.com or www.jennyblanc.com<br />

The charity is currently seeking International Trustees.<br />

Julia is working on a book to support The Crane foundation – for<br />

the protection of birds.<br />

PETAL ‘Painting and Everything Else’. Registered charity no. 1120847<br />

workings; the two sided coin of mystery<br />

and discovery, last seen when I first<br />

played Oblivion as a wide eyed youngster,<br />

has returned in force.<br />

© ZeniMax Media<br />

Collage © Julia Whatley