ven-a-comer-e-book-en_1

ven-a-comer-e-book-en_1

ven-a-comer-e-book-en_1

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

g<strong>en</strong>eral COORDINATION:<br />

María Luisa Sabau García<br />

TEXT AND FIELD CoordinaTION:<br />

Arisbeth Araujo Gómez<br />

Adalberto Ríos Lanz<br />

pHOTOGRAPHY:<br />

Fernando Gómez Carbajal: RECIPES, pAGEs: 13, 43,<br />

61, 75, 83, 93, 107, 115, 125, 139, 147, 157, 171, 179, 189, 203, 211 Y 221;<br />

AND DISHES, PRODUCTS AND ENVIRONMENT.<br />

Adalberto Ríos Lanz AND Adalberto Ríos Szalay.<br />

DISHES, PRODUCTS AND ENVIRONMENT.<br />

Nacho Urquiza / Laura Cordera, STYLING. DESSERTS,<br />

pAgEs: 69, 101, 133, 165, 197 and 229.<br />

Consejo de promoción Turística de México: p. 46 ABOVE;<br />

p 103 LOWER LEFT; p. 167 MIDDLE; p. 199 UPPER RIGHT; p. 205 UPPER<br />

RIGHT; p. 209 LOWER RIGHT.<br />

DESIGN:<br />

Danilo Design Group<br />

eduardo danilo ruiz<br />

Marcela Rivas / Erika Sosa<br />

TraNSLATION:<br />

Debra Nagao<br />

Anne HILL DE Mayagoitia<br />

COPYEDITING, PROOFREADING, SPANISH:<br />

María Ángeles González<br />

COPYEDITING, PROOFREADING, ENGLISH:<br />

ANNE HILL DE MAYAGOITIA<br />

ISBN: 978-607-96687-3-0<br />

© All rights reserved. The partial or total reproduction of this work by<br />

any means or procedure, including reprography and digital reproduction,<br />

photocopying, and filming is prohibited without writt<strong>en</strong> permission<br />

of the copyright holders of this edition.

CONTENTS<br />

VEN A COMER<br />

SAVOR MEXICO<br />

sea<br />

and desert<br />

the c<strong>en</strong>tral<br />

pacific coast<br />

BETWEEN<br />

TWO OCEANS<br />

THE<br />

NORTHEAST<br />

COUNTRY<br />

AND CITY<br />

THE<br />

SOUTHEAST<br />

Foreword<br />

claudia ruiz massieu 7<br />

Come to Eat<br />

Mexico<br />

Gloria López Morales 11<br />

Conquered by Mexico!<br />

Joan Roca 15<br />

Mexican Cuisine,<br />

a Mill<strong>en</strong>ary History<br />

Yuri de Gortari /<br />

Edmundo Escamilla 19<br />

Traditional Mexican<br />

Cuisine<br />

Marco Bu<strong>en</strong>rostro 27<br />

Sweet Land<br />

martha ortiz 33<br />

The Basis<br />

of Our Cuisine 34<br />

Sea and Desert 38<br />

FISH OF THE DAY 42<br />

A Fusion of Traditions<br />

Jair Téllez 44<br />

COLD AND WARM<br />

SHELLFISH manzanilla 50<br />

The Tomato,<br />

Mexican Heart<br />

Martha Chapa 54<br />

CARROT SOUP WITH<br />

PARTRIDGE FOAM 60<br />

Mexican Wine<br />

Hugo D’Acosta 62<br />

Coyotas<br />

nacho urquiza<br />

Pemoles de Maíz<br />

martha ortiz 68<br />

The C<strong>en</strong>tral<br />

Pacific Coast 70<br />

JICAMA AND<br />

jamaica ROLLS 74<br />

West Mexico<br />

Nico Mejía 76<br />

GREEN ceviche 82<br />

The Avocado<br />

Rubi Silva 86<br />

BEEF RIBS<br />

AU JUS 92<br />

May I Offer<br />

You a Mezcal?<br />

cornelio Pérez<br />

(Tío Corne) 94<br />

Jericalla<br />

Pepitorias 100<br />

Betwe<strong>en</strong> Two Oceans 102<br />

FILLED OCOSINGO<br />

CHEESE 106<br />

The Delicacies<br />

of Gre<strong>en</strong> Lands<br />

Adalberto<br />

Ríos Szalay 108<br />

BEAN ROLL 114<br />

Mexico and<br />

Its Cheeses<br />

Carlos Yescas 118<br />

HOJA SANTA ROLLS 124<br />

The Many Faces<br />

of Mexican Coffee<br />

Jesús Salazar 126<br />

Nicuatole<br />

Camotes 132<br />

The Northeast 134<br />

chilES STUFFED<br />

WITH cabrito<br />

<strong>en</strong> confit 138<br />

Cooking<br />

and the Result<br />

Adrián Herrera 140<br />

pork belly TACOS 146<br />

Cabrito, Flavor<br />

of the Northeast:<br />

Abdiel Cervantes 150<br />

cabrito <strong>en</strong> fritada 156<br />

The Navigable Rivers<br />

of Beer in Mexico<br />

Ricardo Bonilla 158<br />

Cocada<br />

Galletitas de Pinole 164<br />

Country and City 166<br />

FLOATING PRICKLY<br />

PEAR PADS 170<br />

Cuisine in the Valley<br />

of Mexico<br />

Alonso Ruvalcaba 172<br />

LAMB MixioteS WITH<br />

PRICKLY PEAR PAD SALAD 178<br />

Maize<br />

alicia gironella 182<br />

tilapia ROASTED<br />

OVER A pirul WOOD<br />

FIRE WITH milpa SALAD<br />

AND WHITE escabeche 188<br />

Pulque<br />

JOSÉ N. ITURRIAGA 190<br />

Buñuelos<br />

Pirulís 196<br />

The Southeast 198<br />

ONIONS WITH<br />

recado negro 202<br />

Southeast Mexico<br />

Ricardo Muñoz Zurita 204<br />

fish in season, GREEN<br />

APPLE, AND SEAWEED<br />

AGUACHILE 210<br />

Spiciness for the World<br />

Lalo Plasc<strong>en</strong>cia 214<br />

SLOW-ROasted LAMB BELLY,<br />

caulilower and eggplant<br />

purée with tubers 220<br />

Libations of Fire and Ice<br />

Héctor Galván 222<br />

Dulce de Zapote<br />

Pan de Muerto 228<br />

mexican GASTRONOMY GLOSSARY 231<br />

◄<br />

4 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer cont<strong>en</strong>ts — 5

MEXICO IS ONE OF a HANDFUL OF MEGADIVERSE COUNTRIES. ITs<br />

borders HOUSE TWELVE PERCENT OF THE PLANET’S DIVERSITY,<br />

ALONG WITH most OF THE WORLD’S EXtanT ECOSYSTEMS.<br />

Mexico is the result of its mill<strong>en</strong>ary culture, <strong>en</strong>riched by the wisdom<br />

of its pre-Hispanic peoples and the innovations brought by<br />

immigrants from other countries.<br />

The wealth of Mexican gastronomy, above all else, stems from the soil that<br />

produces its ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts. Its cuisine is heterog<strong>en</strong>eous and changes radically<br />

from one place to another just a few kilometers away. The same can be<br />

said of the varieties of its raw materials—and the unforgettable flavors—in<br />

markets, homes, and restaurants that maintain allegiance to the banner of<br />

traditional recipes, although they have no fear of experim<strong>en</strong>ting giving them<br />

a contemporary twist. It is a cuisine of many branches, many possibilities,<br />

always ready to be explored.<br />

In rec<strong>en</strong>t years gastronomy has be<strong>en</strong> in the spotlight on the world’s stage and<br />

Mexico’s cuisine has shined for its complexity, tradition, and op<strong>en</strong>ness to new<br />

tr<strong>en</strong>ds, thanks to the professionalism of a large number of contemporary chefs.<br />

In November 2010 unesco singled out traditional Mexican cuisine as<br />

Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. And so, more people have become<br />

6 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer VEN A COMER — 7

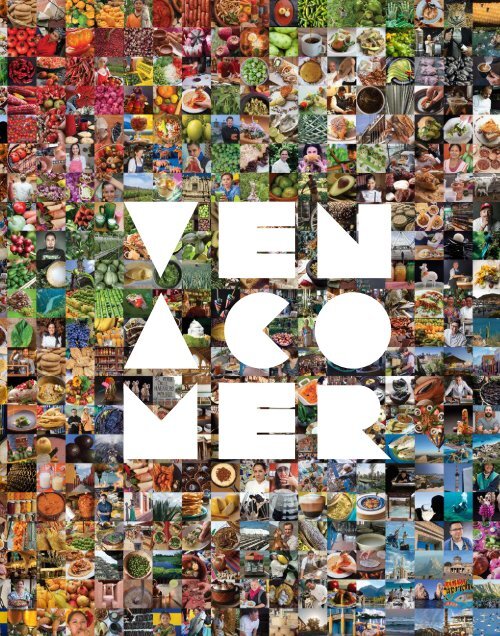

V<strong>en</strong> a Comer<br />

(Savor Mexico)<br />

arose as a project<br />

to invite the world<br />

to visit Mexico<br />

through its<br />

gastronomy.”<br />

aware of the extraordinary attributes of our cuisine and are interested in<br />

experi<strong>en</strong>cing it in depth, which makes this another reason to visit us, in<br />

addition to our marvelous beaches, <strong>en</strong>ormous cultural wealth, and varied<br />

ecosystems.<br />

V<strong>en</strong> a Comer literally “come to eat” is an emerging project to invite the<br />

world to visit Mexico through its gastronomy. With “come to eat,” mothers<br />

traditionally call the family to join around the table at mealtime, and it is<br />

part of the invitation from Mexicans who op<strong>en</strong> the doors of their home to<br />

share a hospitable meal. It is an inclusive invitation, where many palates come<br />

together to discover good Mexican cooking.<br />

This <strong>book</strong> beckons the reader to savor Mexico’s recipes and is, at the<br />

same time, a repository of its history, a sampling of the multiplicity of its<br />

ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts and a record of its important day-to-day life. The p<strong>en</strong>s of all the<br />

authors who contributed to this <strong>book</strong> trace a historical and geographical<br />

pathway of food across Mexico: some describe the c<strong>en</strong>ter, northeast,<br />

northwest, or southeast of the country; others tempt us with beverages such<br />

as mezcal; with iconic ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts such as corn, tomatoes, and chiles; or with<br />

emblematic desserts.<br />

From their distinct vantage points the authors of this volume highlight the<br />

intrinsic value of Mexican gastronomy. Our int<strong>en</strong>tion is to allow each reader<br />

to approach it from differ<strong>en</strong>t angles with an interest sparked by curiosity to<br />

know more about it.<br />

V<strong>en</strong> a Comer is more than an invitation to sit down at the table; it is a<br />

proposal to discover the delicious compon<strong>en</strong>ts of a cuisine that today is one of<br />

the most highly regarded in the world.<br />

claudia ruiz massieu<br />

MINISTER OF TOURISM<br />

8 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer VEN A COMER — 9

come to eat<br />

Mexico<br />

n Gloria López Morales<br />

UNESCO has recognized Mexico’s delicious traditional cuisine as<br />

Intangible Cultural Heritage. Now we must care for it because it<br />

is, and always has be<strong>en</strong>, the foundation of our country’s survival<br />

and developm<strong>en</strong>t.<br />

Although this is an era of globalization, there is an urg<strong>en</strong>t need to affirm our<br />

unique cultural features in the vast map of cultural and natural diversity.<br />

Mexico has traditional farming and harvesting methods for the food that is<br />

transformed in the kitch<strong>en</strong> into the same dishes our ancestors made.<br />

Mexican cuisine is based on products from the milpa—the core of the<br />

agricultural system: corn, beans, chile, and about sixty other products.<br />

They are grown everywhere in Mexico and through time have be<strong>en</strong> the basis<br />

of our diet.<br />

While it is true that greater diversity <strong>en</strong>riches cuisine, it should be<br />

pointed out that Mexico boasts considerable culinary creativity that<br />

distinguishes its regional cuisines. Beyond the superb quality of the<br />

ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts, this creative capability is what <strong>en</strong>ables the special touch of<br />

expertise that a cook or chef brings to cooking to shine through.<br />

In this country people have always had a joyful vision of food. What<br />

changed with the unesco recognition was the level of awar<strong>en</strong>ess that we<br />

now have about this cultural heritage: the understanding that good cooking<br />

10 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer come to eat mexico — 11

Mexican<br />

cuisine is<br />

a complex<br />

living art.”<br />

Cuitlacoche<br />

(huitlacoche) is a<br />

fungus that grows on<br />

t<strong>en</strong>der ears of corn<br />

and is regarded as<br />

a culinary delicacy.<br />

Recipe by Jorge<br />

Vallejo, Quintonil.<br />

is not just the fleeting mom<strong>en</strong>t of a well-appointed table, but that it is part<br />

of a long chain of production and creation that implies the need to create<br />

the means to safeguard and promote the <strong>en</strong>tire system.<br />

In this overarching vision tourism plays a decisive role in stimulating<br />

regional and local cuisines. Knowledgeable travelers prefer to taste foods<br />

they do not eat at home.<br />

Mexican cuisine, as a living, complex art, is curr<strong>en</strong>tly undergoing a boom<br />

as we see it. On the one hand there are so many food festivals that they no<br />

longer fit on the cal<strong>en</strong>dar; now you can easily find village fairs, festivals,<br />

celebrations honoring the local patron saint, other kinds of fiestas, harvest<br />

festivals, and the like where food and drink are pl<strong>en</strong>tiful.<br />

On the other hand the explosion of the gastronomic ph<strong>en</strong>om<strong>en</strong>on has<br />

fostered highly productive exchange involving cuisines from other countries<br />

and the winds of innovation have inspired countless young chefs to produce<br />

amazing cuisine that bl<strong>en</strong>ds the intrinsic relation betwe<strong>en</strong> the plate and the<br />

planet and the virtues of a healthy, well-balanced traditional diet based on<br />

local products.<br />

Dear visitor, <strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>ture along the Pacific coast or the Gulf of Mexico, but<br />

also travel through the Bajío region and the highlands where the land is a<br />

g<strong>en</strong>erous provider. Go to Puebla, Oaxaca, Michoacán, and Chiapas—<br />

sanctuaries of indig<strong>en</strong>ous and mestizo cuisine—where there is a marvelous<br />

custom of dressing the table with cutlery and hand-crafted objects that give<br />

dining a ritual meaning surrounded by beauty. The Maya world alone is a<br />

foodie’s paradise with unmistakable ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts and techniques and<br />

ing<strong>en</strong>ious use of spices. And th<strong>en</strong>, go to the capital, Mexico City, the place<br />

that has it all.<br />

Hand in hand with tradition, we can see the creativity of new chefs in the<br />

modernized kitch<strong>en</strong>. They are showing the whole world that fine Mexican<br />

cuisine is as old as time and as new as this very mom<strong>en</strong>t.<br />

■■■<br />

12 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer come to eat mexico — 13

Conquered<br />

by Mexico!<br />

n joan roca<br />

My first trip to Mexico in 1991 coincided with my falling for the<br />

universal passion for gastronomy. I remember it as the mom<strong>en</strong>t<br />

wh<strong>en</strong> many of us became interested in observing the stock of<br />

food and cultural wealth of other cuisines and learning about<br />

the whole world.<br />

This was a trip with historical Catalonian chefs, leaders of a g<strong>en</strong>eration prior to<br />

mine. Master chefs such as Joan Duran, of the Hotel Presid<strong>en</strong>t of Figueres; Pepe<br />

Tejero, from Las Marinas in Gavà, and Ramon Balsells of La Pineda in Gavà. We<br />

chatted <strong>en</strong>dlessly, exchanging ideas and experi<strong>en</strong>ces. We learned so much. I<br />

fell in love with Mexico and La Galvia restaurant that was run by Mónica<br />

Patiño, in Polanco, an area in Mexico City, and became <strong>en</strong>thusiastic about her<br />

creativity and modern ways of working that she had learned in France and<br />

used to modernize Mexican cuisine. At that time in Mexico there were many<br />

people who saw themselves as heirs of a great tradition and were well<br />

acquainted with the complexities of producing it.<br />

At that time also there was a <strong>book</strong> that impressed me: Like Water for<br />

Chocolate by Laura Esquivel was published in 1989 and made into a movie by<br />

Alfonso Arau in 1992. I am not going to go into what a ph<strong>en</strong>om<strong>en</strong>on this film<br />

was, but I do want to m<strong>en</strong>tion that thanks to it, the <strong>en</strong>tire world discovered the<br />

wealth of Mexican cuisine highlighted in the <strong>en</strong>gaging plot.<br />

Since th<strong>en</strong> I have made several trips throughout Mexico where I have be<strong>en</strong><br />

able to delve into the gastronomy and especially into foodstuffs and the<br />

leg<strong>en</strong>dary way food is handled. The culinary culture is deeply rooted and part<br />

of the Mexican character, while it also has the <strong>en</strong>ergy of modern cuisine. It is a<br />

cuisine that is about to eat the world alive. I don’t need to point out that the<br />

food items cultivated in that vast country are the base of many traditional<br />

dishes worldwide, especially in Europe.<br />

From Mestizaje to Fusion<br />

Fusion, the interaction betwe<strong>en</strong> cultures, is an offshoot of the worldwide<br />

interest in diversity. It is inevitable in most disciplines today, as megabytes of<br />

data flood in. However, wh<strong>en</strong> the world started to become globalized, wh<strong>en</strong><br />

14 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer conquered by meXICO! — 15

The basis<br />

of Mexican<br />

cuisine is<br />

mestizaje.”<br />

Pre-Columbian and European cultures bl<strong>en</strong>ded together, that fusion was called<br />

mestizaje. It resulted in Creoles and for a long time was se<strong>en</strong> as something<br />

pejorative or unimportant.<br />

Not today, however. Fusion is se<strong>en</strong> as a positive factor, something that has<br />

made us move forward as people. The basis of Mexican cuisine is that<br />

mestizaje, and thanks to it, humankind has made <strong>en</strong>ormous strides. At the<br />

outset we prospered from the fruits of agriculture, especially from the milpa or<br />

corn field: that magical association of corn, beans, and squash, and at times<br />

chilies, too, where each plant gives its best. One holds moisture in the land,<br />

while another fertilizes the soil with nitrog<strong>en</strong> as it twines up the cornstalk in<br />

the shade provided by the maize plant. Se<strong>en</strong> from a distance, it is<br />

extraordinary, magical, almost like following a recipe, perhaps e<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> more<br />

complex. Corn, beans, squash, and chilies—whose name morphed to pepper<br />

and pim<strong>en</strong>to—arrived in Europe with tomatoes and avocados. We have adopted<br />

them all and love them as our own, along with other products from the<br />

Americas, notably potatoes. Moreover, we are passionate about chocolate and<br />

vanilla, which have <strong>en</strong>abled us to concoct glorious desserts.<br />

We have gott<strong>en</strong> a lot from all of these fruits, but, e<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> so, we are way behind<br />

Mexico with its thousands of years of experi<strong>en</strong>ce with them. Until rec<strong>en</strong>tly the<br />

world was not particularly interested but now we are becoming more aware of<br />

all that Mexico has gi<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> us: some of the most popular products in world cuisine.<br />

Thanks to fusion, the republic, and its revolution, this country <strong>en</strong>joys one of<br />

the best and most influ<strong>en</strong>tial of international cuisines. There is now awar<strong>en</strong>ess<br />

of traditions from mill<strong>en</strong>nia and influ<strong>en</strong>ce from across the two great oceans,<br />

the Pacific and the Atlantic. From the c<strong>en</strong>ter of the Americas, called<br />

Mesoamerica, Mexico looks east and west to Europe and to Asia.<br />

We <strong>en</strong>vy this country that is so geographically diverse with varied climates,<br />

agricultural production and culinary interpretations. It does not have food<br />

limitations and restrictions—none at all—in Mexico one can eat everything. We<br />

acknowledge it is the best cuisine in the world, which was summarized in the<br />

landmark decision of the Fifth Meeting of the Intergovernm<strong>en</strong>tal Committee in<br />

K<strong>en</strong>ya in November 2010 wh<strong>en</strong> traditional Mexican cuisine was included on the<br />

In<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>tory of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Mexico, administered by the<br />

governm<strong>en</strong>tal ag<strong>en</strong>cy known as the Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes<br />

(Mexican Council for Culture and the Arts). Two aspects of the unesco<br />

resolution are worth pointing out:<br />

• Traditional Mexican cuisine is c<strong>en</strong>tral to the cultural id<strong>en</strong>tity of the<br />

communities that practice and transmit it from g<strong>en</strong>eration to g<strong>en</strong>eration.<br />

• Traditional Mexican cuisine is a compreh<strong>en</strong>sive cultural model comprising<br />

farming, ritual practices, age-old skills, culinary techniques and ancestral<br />

community customs and manners. It is made possible by collective<br />

participation in the <strong>en</strong>tire traditional food chain, from planting and<br />

harvesting to cooking and eating.<br />

On our trips to Mexico we discovered that corn is not something g<strong>en</strong>eric,<br />

rather it is a fact of life. There are many varieties of corn: they are all maize<br />

but they taste slightly differ<strong>en</strong>t. Talking about corn in Mexico is complex—a<br />

bit like talking about bread in Europe. Making tortillas can be lik<strong>en</strong>ed to a<br />

research and developm<strong>en</strong>t project starting with nixtamalization. The leaves<br />

of the plant are used as wrappers for tamales, and a fungus that grows on the<br />

kernels, called huitlacoche, is surprisingly delicious. We liked the large<br />

number of mole sauces—red, gre<strong>en</strong>, black, and others.<br />

Th<strong>en</strong> we discovered the gre<strong>en</strong> tomatillo. Avocados in their natural state<br />

are delightful. We w<strong>en</strong>t crazy for red achiote. Oaxaca cheese surprised us—it<br />

is similar to mozzarella—bl<strong>en</strong>ded with squash leaves in tortilla turnovers<br />

called quesadillas. We witnessed the miracle of the hoja santa herb in the<br />

kitch<strong>en</strong> and the medicine cabinet. We learned the differ<strong>en</strong>ce betwe<strong>en</strong> tequila,<br />

mezcal, and pulque—all created from maguey. We recognized the agave or<br />

aloe vera as a beautiful Mediterranean plant, until we learned it was brought<br />

there from the Americas along with the nopal or prickly pear.<br />

And, to top it all off, they taught us to toast with the maguey’s offspring to<br />

the health of Mexican cuisine and in thanksgiving for all it has gi<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> us.<br />

■■■<br />

Joan Roca's restaurant, El Celler de Can Roca, is number one on San Pellegrino's List<br />

of the World's 50 Best Restaurants 2015.<br />

In Mexico<br />

you can eat<br />

everything.<br />

It is one of<br />

the most<br />

diversified<br />

cuisines in<br />

the world.”<br />

16 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer conquered by meXICO! — 17

Mexican<br />

Cuisine,<br />

a Mill<strong>en</strong>ary<br />

History<br />

n Yuri de Gortari / Edmundo Escamilla<br />

Not long ago we heard a Fr<strong>en</strong>chman claim that Mexican cuisine<br />

was not new, because it was almost 500 years old. We were<br />

somewhat tak<strong>en</strong> aback by this lack of awar<strong>en</strong>ess of the depth of<br />

our food history. Wh<strong>en</strong> it comes to Mexican gastronomy, we are<br />

talking about a tradition that has be<strong>en</strong> forged over the course<br />

of not merely c<strong>en</strong>turies, but mill<strong>en</strong>nia. Mexican cuisine is the<br />

result of a long and complex developm<strong>en</strong>t of civilization.<br />

Mexico is one of the few places in the world id<strong>en</strong>tified as a cradle of<br />

agriculture, along with the Mediterranean area, Mesopotamia, and Southeast<br />

Asia. The earliest plants that were domesticated were chile and corn. In the<br />

Tehuacán Valley, Puebla, in Tamaulipas and in Oaxaca, archaeological<br />

vestiges of domesticated chile seeds have be<strong>en</strong> found in contexts suggesting<br />

human consumption from 7000 and 5000 BC. This gives us an idea of the<br />

oldest anteced<strong>en</strong>ts of our everyday diet. In no other country has the<br />

consumption of corn and chile be<strong>en</strong> so clearly id<strong>en</strong>tified as in Mexican<br />

contexts at the core of our unique cultural id<strong>en</strong>tity.<br />

By 2000 BC there is clear evid<strong>en</strong>ce of Olmec civilization, regarded by<br />

many as the Mother Culture. By this time various crops that have be<strong>en</strong> the<br />

basis of our diet for c<strong>en</strong>turies were cultivated; the milpa was sowed with<br />

corn, beans, chile, and squash. It has be<strong>en</strong> a farming system aimed at<br />

meeting the needs of personal consumption that has be<strong>en</strong> pro<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> to provide<br />

the most complete range of nutri<strong>en</strong>ts. Moreover, the technique of<br />

18 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer Mexican Cuisine, a Mill<strong>en</strong>ary History — 19

Clearly this<br />

mill<strong>en</strong>ary<br />

cuisine<br />

evolved<br />

in its historical<br />

developm<strong>en</strong>t.”<br />

nixtamalization of corn with lime, ash, or pulverized shells was known by<br />

th<strong>en</strong>, and tools such as grinding bowls to prepare salsas were also in use.<br />

Prior to the Christian Era, the cultivation and consumption of other products,<br />

such as cacao, tomatillo, sweet potato, and jicama, quelites (smooth amaranth),<br />

and prickly pear, were among a variety of products in what is Mexican territory<br />

today. Many of these products are now part of the country’s regional cuisines.<br />

By the third c<strong>en</strong>tury great civilizations emerged in the Americas, perhaps the<br />

most outstanding of which were the Mayas, Teotihuacan, and the Zapotecs. Each of<br />

these cultures possessed advanced agricultural technology that <strong>en</strong>abled them to<br />

establish major urban c<strong>en</strong>ters with an adequate food supply and storage systems,<br />

such as cuexcomates (granaries) in C<strong>en</strong>tral Mexico. The people also used grinding<br />

stones to grind the nixtamal (boiled corn) and finely crafted ceramics, such as<br />

Teotihuacan’s Thin Orange ware, to serve food. In addition to a well-established<br />

diet based on products from the milpa and a wide variety of New World flora and<br />

fauna, they had an evolved diet, with excell<strong>en</strong>t sources of animal and plant protein.<br />

Mexico ranks fifth in terms of biodiversity in the world. All cultures<br />

established here also consumed meat such as rabbit or hare that was found in<br />

fifte<strong>en</strong> varieties, eight of them <strong>en</strong>demic to Mexico. They also ate deer, peccary,<br />

fish, seafood, birds, and reptiles, such as delicious iguana meat, as well as<br />

insects, larvae, and ant eggs.<br />

In the case of the Mayas, they practiced advanced agricultural techniques:<br />

terraced irrigation systems to exploit water to the maximum. They also<br />

practiced slash and burn agriculture, which fertilized the land with ashes from<br />

the charred stubble. Underground wells or chultunes dug in the porous<br />

limestone shelf served for water storage. Their diet was composed of an ample<br />

diversity of foods, including squash, differ<strong>en</strong>t types of beans, such as ibes and<br />

xpelón, chiles such as xcatik and bell peppers, plus a variety of beverages such as<br />

corn-based atoles and pozol. They practiced highly advanced apiculture, because<br />

all home gard<strong>en</strong>s had hives of Melipona bees, which they raised themselves.<br />

The Mayas used a pib, an underground o<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>, to cook tamales or pibes that<br />

continue to be an emblematic dish on the table in Yucatán. These dishes are<br />

served with salsas such as k’ool, thick<strong>en</strong>ed with corn dough. Nature’s<br />

abundance provided them with a wide range of fruit, such as nance, sapodilla,<br />

papaya, black sapote, and ziricote fruit. Their diet also included fish and<br />

seafood, deer, the great curassow, and ocellated turkey.<br />

They built a network of roads called sacbeob or “white roads,” which linked<br />

the principal Maya cities, fostering trade. From the Classic period (200–900),<br />

the Maya maintained trade relations with distant cultures, hundreds of<br />

kilometers away. It should be noted that in the Yucatán P<strong>en</strong>insula, a major<br />

urban c<strong>en</strong>ter was built every 20 kilometers, which suggested a high degree of<br />

social and political organization. However, for this to be possible, the Mayas<br />

must have had a stable source of food production and distribution. Their<br />

decorative arts, some employed in food service, such as handsomely<br />

decorated vessels to consume a hot chocolate beverage, attest to their elevated<br />

cultural developm<strong>en</strong>t. In the sixte<strong>en</strong>th c<strong>en</strong>tury Bishop Diego de Landa noted<br />

that he had never se<strong>en</strong> a people “so tak<strong>en</strong> with a delight for eating.”<br />

By the year 900 Toltec culture in C<strong>en</strong>tral Mexico had embarked upon a<br />

series of conquests, subjugating towns and forcing them to pay tribute, as far<br />

away as those in the Maya region, which led to the fusion of Maya and Toltec<br />

culture. In Toltec mythology, deities display a profound connection with food:<br />

Quetzalcoatl (the feathered serp<strong>en</strong>t) gave cacao to man. This god had<br />

performed autosacrifice to rescue the sacred bones from the Underworld and<br />

to make the Fifth Sun, the land that was populated by human beings. This is<br />

the same god who turned himself into an ant to give corn to humankind.<br />

Another major deity was Tezcatlipoca, the lord who gave and took away riches<br />

who was connected to food-related myths, as in the case of chile.<br />

In the Postclassic period (900–1521) the Xochimilca culture was one of many<br />

inhabiting the Valley of Mexico, along with the former people from<br />

Teotihuacan, who settled in the zone after the gradual abandonm<strong>en</strong>t of their<br />

great city-state, along with migrants from northern lands who brought their<br />

knowledge of mountain farming. In the wetlands in the southern lake region,<br />

they developed chinampa agriculture, which consisted of building floating<br />

islets anchored in the water where they planted ahuejotes (willows). As they<br />

grew, the roots of these trees sought the lake bottom, forming a sort of mesh,<br />

which was filled with soil, mud, and stones. This chinampa cultivation has<br />

survived to the pres<strong>en</strong>t and remains a c<strong>en</strong>ter of agricultural production. By<br />

that time, the consumption of huautli, which naturalist Carl Linnaeus called<br />

amaranth, was widespread.<br />

20 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer Mexican Cuisine, a Mill<strong>en</strong>ary History — 21

In the same period, Totonac culture rose to spl<strong>en</strong>dor in Veracruz and<br />

contributed another ingredi<strong>en</strong>t that transformed world gastronomy: namely,<br />

vanilla.<br />

In 1325 the Aztec established their capital, T<strong>en</strong>ochtitlan, and set out to<br />

build a great empire, with a highly sophisticated system to collect tribute, as<br />

shown in the Codex M<strong>en</strong>doza. We also know of the refinem<strong>en</strong>t of the table of<br />

Emperor Moctezuma, described in the chronicles of conquistador Bernal<br />

Díaz del Castillo and in Hernán Cortés’s letters to King Charles V. For the<br />

Aztecs, the consumption of chía seeds was of major importance, for it was<br />

their third basic staple, which gives us an idea of their knowledge of<br />

nutrition, because now we know that chía is one of the foods richest in<br />

omega-3 fatty acids and calcium.<br />

In the description of the foods most oft<strong>en</strong> consumed by the Mexica people<br />

in the Flor<strong>en</strong>tine Codex, Fray Bernardino de Sahagún m<strong>en</strong>tions mollis, which<br />

means salsa or concoction in Nahuatl. Thanks to Sahagún we know of a range<br />

of dishes such as tamales, pipianes (squash seed sauces), clemoles (chile-laced<br />

sauce), and pozoles (hominy soup) that are still emblematic of Mexican<br />

gastronomy. Since that time Purépecha atápakuas (a rich spicy aromatic sauce)<br />

and corundas (corn dough served with salsa) or uchepos (sweet tamales) were<br />

known from other regions in Mexico, such as Michoacán.<br />

In this way the chroniclers bore witness to the fact that a refined and<br />

complex cuisine was already in exist<strong>en</strong>ce wh<strong>en</strong> the Spaniards arrived. In fact,<br />

it was a tradition that had be<strong>en</strong> developing for more than tw<strong>en</strong>ty c<strong>en</strong>turies and<br />

that continued to be transformed with the arrival of the conquerors. With<br />

them new ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts and techniques, new species and their products were<br />

introduced, such as pork and lard, beef and dairy products, and sheep, to<br />

name a few. Other products included wheat and sugarcane; spices such as<br />

cinnamon, pepper, and cloves, and ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts such as lettuce, radishes, lima<br />

beans, mangoes, limes, oranges, apples and quince; not to m<strong>en</strong>tion hibiscus<br />

flower, bay leaf, and thyme. Sugarcane and wheat, ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts brought by<br />

Hernán Cortés, gave rise to remarkable Mexican baked goods and Mexican<br />

fruit was transformed into beautiful Mexican sweets, fruit pastes, jellies, and<br />

candied fruit. Rabbit meat, once so common, was replaced by pork, while<br />

chiles were filled with beef and its byproduct, cheese.<br />

Little by little this led to gastronomic interbreeding in this culinary melting pot,<br />

where the trade route linking Mexico to the Philippine islands from 1565 to 1815<br />

also played an important role. From there we received a wide variety of spices that<br />

were integrated into our cooking along with mill<strong>en</strong>ary ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts and techniques<br />

with European and African contributions. From the latter region we now <strong>en</strong>joy<br />

molotes (fried meat-filled dough), so traditional in southeastern Mexico.<br />

Turning to music, by the se<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>te<strong>en</strong>th c<strong>en</strong>tury New Spain had acquired its<br />

own highly distinctive features with European harmonies, our percussion and<br />

wind instrum<strong>en</strong>ts having be<strong>en</strong> adapted to Mexican rhythms. Charrería or<br />

horsemanship arose on haci<strong>en</strong>das in c<strong>en</strong>tral Mexico, in ranch work, where the<br />

people took advantage of old underground o<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>s to make barbacoa<br />

(barbecued) sheep; while pibes, as these cooking pits are known in Yucatán,<br />

were employed to roast wild boar, replacing peccaries.<br />

In the same way, countries such as Spain, Italy, and many others in the Old<br />

World saw their cuisine transformed with the new ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts from Mexico—<br />

corn, tomatoes, vanilla, chocolate, and the Mexican turkey—as immortalized in<br />

the palatial banquet depicted by great Italian artist Giulio Romano in the<br />

second half of the sixte<strong>en</strong>th c<strong>en</strong>tury.<br />

Toe-tapping huapangos arose, along with sweet<strong>en</strong>ed bread, lively sones and<br />

pambazos (pork sausage and potato sandwiches), jarabes (hat dances) and<br />

birria (spicy stew). Since the viceregal period food underw<strong>en</strong>t transformations<br />

and regional gastronomies emerged, as we started to add pork to our pozoles<br />

and beef to our clemoles. The tlecuil, the hearth in pre-Hispanic kitch<strong>en</strong>s,<br />

coexisted alongside the portable cooker from Andalusia. In the viceregal<br />

palace in Mexico City the first large-scale banquets in European style were<br />

served, although now with a touch of chile.<br />

In monasteries in New Spain native and European ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts were<br />

combined in bi<strong>en</strong> me sabes (coconut-meringue dessert) and capirotadas (bread<br />

pudding), candied pumpkin, barrel cactus crystalized with sugar, and chocolate<br />

bl<strong>en</strong>ded with sugar and cinnamon. In the se<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>te<strong>en</strong>th and eighte<strong>en</strong>th c<strong>en</strong>turies,<br />

Baroque cuisine exalted the s<strong>en</strong>ses “to reach ecstasy and be in contact with<br />

God.” Pepper, cloves, and cinnamon along with sesame seeds and raisins were<br />

added to pre-Hispanic mole sauces. Chiles and fruit were combined to make<br />

superb stews, such as manchamanteles (meat-chile-fruit stew). With Mexican<br />

So the<br />

chroniclers<br />

recorded<br />

that a refined<br />

and complex<br />

cuisine already<br />

existed wh<strong>en</strong><br />

the Spaniards<br />

arrived.”<br />

22 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer Mexican Cuisine, a Mill<strong>en</strong>ary History — 23

In the same<br />

way, countries<br />

such as Spain,<br />

Italy, and many<br />

others in the<br />

Old World saw<br />

their cuisine<br />

transformed<br />

with the new<br />

ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts<br />

from Mexico<br />

—corn, tomatoes,<br />

vanilla, chocolate,<br />

and the Mexican<br />

turkey.”<br />

Indep<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>ce, cooks experim<strong>en</strong>ted with nut sauce, which can be found in<br />

eighte<strong>en</strong>th-c<strong>en</strong>tury cook<strong>book</strong>s now accompanying a remarkable dish: chiles <strong>en</strong><br />

nogada (meat-stuffed peppers with creamy walnut sauce), which Russian<br />

filmmaker Sergei Eis<strong>en</strong>stein declared to be the most extraordinary delicacy he<br />

had ever tasted.<br />

After Mexican Indep<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>ce, the country was in direct commercial contact<br />

with other European powers that, just as the rest of Latin America and the<br />

United States, followed Fr<strong>en</strong>ch protocol. This was a consequ<strong>en</strong>ce of the fact<br />

that at this time France dictated the norms of diplomacy.<br />

Mexican cuisine, which id<strong>en</strong>tifies us to the world, was largely consolidated<br />

by the start of Indep<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>t Mexico. Despite its adher<strong>en</strong>ce to Fr<strong>en</strong>ch protocol<br />

in official circles, in the intimacy of the home or in the large-scale celebrations<br />

on haci<strong>en</strong>das, more traditional Mexican food was on the m<strong>en</strong>u: tamales, mole<br />

sauces, barbacoa, carnitas (braised pork), tejocotes (Mexican hawthorn fruit) in<br />

syrup or in jelly or as fruit paste.<br />

By 1849 marquise Calderón de la Barca wrote about Veracruz food,<br />

id<strong>en</strong>tifying it as such. She said the first time that she tasted it, upon her arrival<br />

in Mexico at that port, she did not like it at all, but wh<strong>en</strong> she tried it again, it<br />

was delicious. Her advice to travelers was that they needed to reassess their<br />

prejudices. Only a woman of her tal<strong>en</strong>t could have made this comm<strong>en</strong>t,<br />

because it was difficult for ninete<strong>en</strong>th-c<strong>en</strong>tury Europeans to understand<br />

customs and cuisines other than their own.<br />

The ninete<strong>en</strong>th c<strong>en</strong>tury was marked by invasions of Mexico, which had an<br />

impact on gastronomy and customs. The same occurred with migrations of<br />

people from France, Italy, Germany, Lebanon, China, and Japan to Mexico at<br />

the <strong>en</strong>d of that c<strong>en</strong>tury.<br />

With the era of Porfirio Díaz and the start of the tw<strong>en</strong>tieth c<strong>en</strong>tury, the<br />

influ<strong>en</strong>ce of Fr<strong>en</strong>ch cuisine was strong in elite circles. New establishm<strong>en</strong>ts,<br />

such as cafés, were consolidated, while small restaurants continued to serve<br />

traditional Mexican dishes: soup and rice or pasta, the main dish accompanied<br />

by beans, and dessert at the <strong>en</strong>d. Indoor markets, where Pablo Neruda said the<br />

“spirit of Mexico” could be found, existed alongside con<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>i<strong>en</strong>ce stores and<br />

corner shops and with the appearance of canned products, such as sardines.<br />

Italian pastas became part of everyday fare, although baked.<br />

With the Mexican Revolution we explored our deepest roots and<br />

ultimately ushered in political power with a strong indig<strong>en</strong>ous or rural<br />

t<strong>en</strong>d<strong>en</strong>cy, unaccustomed to European cuisine, but rather to dishes of more<br />

autochthonous origin. They served traditional Mexican banquets. By 1920,<br />

with José Vasconcelos’s educational policy, the need for Mexicans to reflect<br />

on our own culture drove great artists to paint murals on the history and<br />

daily life of Mexico on the massive walls of viceregal buildings. In this way we<br />

saw ourselves reflected in the obsidian mirror of Tezcatlipoca and we<br />

recognized ourselves peering into the soul of Mexico. Soda fountains became<br />

popular and there was a rise in quality restaurants in both the capital and the<br />

provinces.<br />

Later in the 1940s, Mexico received waves of Spanish Republicans and<br />

refugees of diverse nationalities. It welcomed them with a tasty morsel and an<br />

embrace, and appreciation for the mark they left and their culinary customs.<br />

The revolution in household appliances contributed to the evolution of<br />

Mexican cuisine, as well as the ever-growing impact of the mass media: radio<br />

and TV, and more rec<strong>en</strong>tly the internet, which made their contribution to the<br />

Mexican diet. By the 1980s, gastronomy as a media ph<strong>en</strong>om<strong>en</strong>on rose in<br />

importance and the media began to tout Nouvelle Mexican Cuisine. This had<br />

an effect particularly in urban settings and on the restaurant industry.<br />

For the vast majority of people, traditional Mexican food continues to rule<br />

their diet. However, popular fairs serve buñuelos (deep-fried dough) and birria,<br />

as well as pancakes, known as hotcakes and now a Mexican tradition, served<br />

with cajeta (carmelized milk) or marmalade.<br />

In the 1990s and the tw<strong>en</strong>ty-first c<strong>en</strong>tury, we live in times of change and<br />

new influ<strong>en</strong>ces. With the spread of the media and social networks, these<br />

novelties will gain force, but only time will tell if they have a lasting impact on<br />

Mexican cuisine, which in most cases reveals the idiosyncrasy of a nation.<br />

Meanwhile, as we wait to see what the future holds, as the Strid<strong>en</strong>tist artist<br />

from the 1920s, Germán List Arzubide, put it:<br />

Long live turkey in mole sauce!<br />

■■■<br />

Traditional<br />

Mexican food<br />

was on the<br />

table: tamales,<br />

moles,<br />

barbacoa,<br />

carnitas,<br />

tejocotes in<br />

syrup or in jelly<br />

or as fruit paste.”<br />

24 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer Mexican Cuisine, a Mill<strong>en</strong>ary History — 25

Traditional<br />

Mexican<br />

Cuisine<br />

n marco bu<strong>en</strong>rostro<br />

Farming has be<strong>en</strong> a way of life in what is now Mexico for at<br />

least t<strong>en</strong> thousand years. Unlike other cultures that developed<br />

single-crop agriculture, here techniques that were based on<br />

multiple crops were devised and disseminated. This is the case<br />

of the milpa, from the Nahuatl mili, culture, and pan, place. This<br />

cultural project of domestication, adaptation, dissemination,<br />

and traditional improvem<strong>en</strong>t started in antiquity and<br />

continues to our times.<br />

Rosalba Morales,<br />

traditional cook from<br />

Michoacán.<br />

Groups of hunter-gatherers developed the first techniques that w<strong>en</strong>t into<br />

cooking: selection of ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts, dehydration, roasting, grinding, and<br />

others. Successive advances <strong>en</strong>abled the in<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>tion of local techniques such<br />

as steaming, the use of earth o<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>s, the drying and smoking of chiles, and<br />

drying and salting of meat and fish. Around 1536 Álvar Núñez Cabeza de<br />

Vaca observed how the cultures in the north had steamers to cook food in<br />

gourds. The so-called mezcal cultures developed techniques to obtain food<br />

from the sotol plant (Dasilirión Berlandieri), in ways similar to what we now<br />

use for barbecue: steaming food in a ground o<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>. Other techniques were<br />

grilling and frying.<br />

Francisco Hernández, who was in Mexico betwe<strong>en</strong> 1574 and 1577, wrote<br />

that maguey (agave) was a source of pulque, sugar, and vinegar. In Alonso<br />

de Molina’s Vocabulario, writt<strong>en</strong> in 1571, three names are gi<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> for the<br />

molinillo, the implem<strong>en</strong>t used to whip the chocolate drink into a frothy<br />

beverage. Rec<strong>en</strong>t archaeological studies have determined that the Capacha<br />

culure, from the southern part of today’s state of Jalisco, used special<br />

containers for distillation.<br />

26 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer Traditional Mexican Cuisine — 27

Fish and<br />

shellfish<br />

from Mexico’s<br />

ext<strong>en</strong>sive<br />

coastlines<br />

and its inland<br />

waters are<br />

grilled, served<br />

in ceviches and<br />

cocktails, and<br />

turned into a<br />

varied array of<br />

cooked dishes.”<br />

As corn was improved and adapted, specific varieties of maize were<br />

created such as a dry popcorn type or a moister cacahuacintle for pozole<br />

(hominy stew). The zapalote chico type is used to make totopos (tortilla chips)<br />

in Oaxaca; they are a dry sort of tortilla especially appropriate for travel<br />

rations. In the northern states of Sonora and Sinaloa the coricos or tacuarines,<br />

a popular kind of cookie or cracker, are made from t<strong>en</strong>der corn from Sonora.<br />

Other varieties of maize were created: some suitable for making dough<br />

malleable <strong>en</strong>ough to make tortillas, while other varieties have many other<br />

uses. Wh<strong>en</strong> a cook has several types on hand, a specific one is used for a<br />

gi<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> dish. The systematic work of farmers has resulted in sixty-four native<br />

varieties of corn and thousands of types adapted to differ<strong>en</strong>t ecosystems<br />

and preferred by local cooks.<br />

Nixtamalization of corn, a process that releases niacin and assimilable<br />

calcium, is another important technological contribution of anci<strong>en</strong>t Mexico<br />

to the world. Tortillas made from nixtamalized dough have differ<strong>en</strong>t<br />

diameters, thicknesses, and colors; there are differ<strong>en</strong>t ways to grind the<br />

corn used for tlayudas (large thin tortilla with toppings), tostada-like<br />

chalupas and raspadas, thick filled p<strong>en</strong>eques or memelas, and unfilled<br />

tlatlaoyos. The broad-ranging white corn can be converted into tortillas<br />

used in the preparation of tacos, <strong>en</strong>chiladas, chilaquiles, and quesadillas<br />

with unique flavors specific to each region of Mexico.<br />

The same thing happ<strong>en</strong>s with tamales, as they vary in both form and<br />

flavor and are wrapped in differ<strong>en</strong>t kinds of leaves. In one <strong>book</strong> there are<br />

300 recipes for tamales with their particularities, corresponding to the<br />

distinct geographical zones. The beverage known as atole also tastes<br />

differ<strong>en</strong>t from one region to the next<br />

Around 118 food plants are native to Mexico including beans, tomatoes,<br />

chiles, sweet potatoes, amaranth, chía, vanilla, cacao, and many kinds of<br />

fruit such as pineapple and papaya. Many of them are now part of diverse<br />

gastronomies in other parts of the world.<br />

Chiles are a typical ingredi<strong>en</strong>t in traditional cuisine, used as a condim<strong>en</strong>t<br />

in numerous salsas. They are also used as a container, as in the case of<br />

stuffed chiles, for which there are more than 350 recipes. They are added to<br />

give color to food preparations, and their flexibility makes them ideal for<br />

adding aroma and flavor to mole sauces, salsas, stews, and soups. Curr<strong>en</strong>tly<br />

more than 200 differ<strong>en</strong>t chiles with specific qualities are grown and<br />

harvested and used in regional cuisines. Furthermore, tomatoes can be<br />

found in soups, salsas, salads, and other dishes.<br />

The widespread tradition of hunting and fishing, along with the<br />

domestication of livestock permitted easy access to animal protein. Fish and<br />

shellfish from Mexico’s ext<strong>en</strong>sive coastlines and its inland waters are grilled,<br />

used in ceviches and cocktails, and turned into many kinds of cooked dishes.<br />

Since Antiquity a number of flowers have be<strong>en</strong> cooked and served in the<br />

kitch<strong>en</strong>; we have counted more than forty of them. The consumption of<br />

insects is another source of well-being and <strong>en</strong>joym<strong>en</strong>t. Gre<strong>en</strong>s from the<br />

milpa, flowers, and fruit are seasonal delicacies that are eagerly awaited.<br />

Local fruits are transformed into drinks, whether fresh or ferm<strong>en</strong>ted and<br />

distilled. We can m<strong>en</strong>tion pulque, tesgüino, balché, mezcals and tequilas,<br />

and there are others as well.<br />

Many objects devised by the advanced cultures that dwelled in these lands<br />

can be found as cooking implem<strong>en</strong>ts in traditional kitch<strong>en</strong>s. They are made<br />

from a wide array of materials, such as stone, clay, wood, calabash (Lag<strong>en</strong>aria<br />

siceraria) shells, and gourds (Cresc<strong>en</strong>tia cujete). Some relics were decorated<br />

with techniques used e<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> today, such as incised lacquer from Olinalá,<br />

Guerrero. There are archaeological remains of a wide range of ceramic pieces,<br />

including two-tier plates, steamers, trays, distillers, griddles, salsa containers,<br />

small braziers to keep food warm, bottles, footed bowls, large basins known as<br />

apaxtles, o<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> dishes, pitchers, squat cups and taller drinking vessels, strainers,<br />

and graters. Although they have changed over time, most are still used today.<br />

Two other kitch<strong>en</strong> ut<strong>en</strong>sils that have not fall<strong>en</strong> by the wayside are the<br />

metate (grinding stone) and the molcajete (grinding bowl), ideal for<br />

crushing, whether by friction, impact, or pressure. During the pre-Hispanic<br />

era and until the se<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>te<strong>en</strong>th c<strong>en</strong>tury, besides obsidian knives and blades,<br />

they used maguey fibers for cutting.<br />

Within Mexico there are cultures with their own character and an<br />

<strong>en</strong>during ongoing history. Today wh<strong>en</strong> we talk about traditional Mexican<br />

cuisine, it is understood to refer to all of the cuisines of the indig<strong>en</strong>ous<br />

groups in addition to regional cooking.<br />

28 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer Traditional Mexican Cuisine — 29

Mexican<br />

gastronomy<br />

today offers<br />

wide-ranging<br />

possibilities<br />

for exploring<br />

vast areas<br />

where we<br />

<strong>en</strong>counter<br />

new<br />

s<strong>en</strong>sations<br />

and tastes.”<br />

Before contact with the Europeans, the cuisine of the vibrant advanced<br />

cultures that inhabited these lands was already completely formed. After<br />

contact with other latitudes, each of today’s cultures has be<strong>en</strong> able to<br />

appropriate for itself and further develop how to use ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts from<br />

abroad. This is the case of the Philippines. Every one of the Manila galleons<br />

brought ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts as well as techniques to Acapulco. We adopted them<br />

and gave them a local touch. One example is the mango or the technique for<br />

making a refreshing drink known as tuba from the coconut palm. The<br />

Europeans brought wheat, sugarcane, cattle, sheep, and goats to the New<br />

World and all of these have be<strong>en</strong> integrated into Mexican cuisine.<br />

An anci<strong>en</strong>t technical concept that is a constant and helped diminish the<br />

human impact on nature is the idea of using diverse parts of a species. For<br />

instance, differ<strong>en</strong>t parts of plants are used at differ<strong>en</strong>t stages of the plant’s<br />

maturity. This technique is employed with corn, squash, maguey, beans,<br />

and chiles, among others.<br />

Mexican gastronomy today offers wide-ranging possibilities for exploring<br />

new s<strong>en</strong>sations and tastes. Anywhere this rich and varied cuisine is<br />

prepared, we can expect surprises and opportunities to find out about and<br />

take part in new experi<strong>en</strong>ces. If we focus on the <strong>en</strong>vironm<strong>en</strong>t, it is equally<br />

surprising to note how cooking ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts and other products have<br />

changed in tandem with the ecosystems of the differ<strong>en</strong>t regions or<br />

according to the cultures that produced these refined expressions.<br />

The wealth of our cuisine is part of our id<strong>en</strong>tity and is based on natural<br />

and cultural diversity. Traditional cooking is pres<strong>en</strong>t in most Mexican<br />

homes and adheres to processes of continuity and change in a natural way.<br />

Parallel to this, many chefs trained in specialized schools come up with<br />

new approaches and attempts to innovate preparations and pres<strong>en</strong>tations.<br />

There are also groups that align their proposals with what is curr<strong>en</strong>tly<br />

tr<strong>en</strong>dy. An example of this is the so-called “kitch<strong>en</strong> on wheels.” Others<br />

assign new names to ways they attempt to make new <strong>en</strong>during classics by<br />

taking elem<strong>en</strong>ts from traditional cuisine that they call new, avant-garde,<br />

modern, innovative, contemporary, up-to-date. In cosmopolitan cities it is<br />

possible to eat dishes from other parts of the world and, of course, those<br />

that are traditional in Mexico.<br />

If we <strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong>ture out of the city to smaller communities, there are pl<strong>en</strong>ty of<br />

places where we can approach our flavors: restaurants, small eateries,<br />

markets, establishm<strong>en</strong>ts that serve traditional Mexican dishes, and<br />

restaurants specializing in supper. For an opportunity to sample food<br />

specially made for celebrations, a visitor can try to approach the fiesta site<br />

and if he or she shows interest, it is highly likely that the individual will be<br />

welcomed as a guest and invited to take part in the festivities.<br />

Without exaggeration, it would be fair to say that few countries can offer<br />

an array of traditional cuisine as broad as Mexico’s.<br />

■■■<br />

30 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer Traditional Mexican Cuisine — 31

Sweet Land<br />

n marTHA ORTIZ<br />

Mexican candy-making can be lik<strong>en</strong>ed to a filigree of honey and<br />

sugar that exquisitely embroiders our gastronomic history and<br />

distinguishes our legacy as masters of supreme tal<strong>en</strong>t.<br />

The alfeñiques<br />

are fantastic<br />

animals<br />

that define an<br />

ideal world.<br />

Our candies, as complex as our history, are figurative repres<strong>en</strong>tations of an<br />

“ideal world” created with fantasy and magic. They are a finished mise <strong>en</strong><br />

scène of flavors in a script that in the great gastronomic theater were t<strong>en</strong>derly<br />

hand-painted to win favors or delight saints or sinners with the brilliant<br />

palette of Mexican colors and the unique hues of a master artisan.<br />

These colors, whose contrast, vibrancy, and design, together with exotic<br />

and sublime ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts (terms applied by Mexicans and foreigners alike)<br />

confirm the phrase “made from chile, sugar, and short<strong>en</strong>ing” with a shower<br />

of these sugary, salty, and chile-kissed delights. Moreover, candies can have<br />

beautiful paper wrappers or colorful outer coatings, or else they can be<br />

exhibited almost naked in their outer flesh of corn or s<strong>en</strong>sual fruit. They can<br />

also be se<strong>en</strong> as day-to-day fare or be dressed up for fiestas and ceremonies.<br />

Ingredi<strong>en</strong>ts such as tamarind, coconut, cacao, vanilla, natural or popped<br />

corn, amaranth, sweet potatoes, and fruits sweet<strong>en</strong>ed with caramel or<br />

perfumed with lovely flowers and leaves, form a perfect union, lovers in our<br />

culinary cosmos, stars shining by day or blazing in a dark night. And the<br />

gastronomic narrative continues, because these candies are of noble birth<br />

and are aptly named in the lyrical poetry that distinguishes our cuisine.<br />

Smiles of joy, death and resurrection in the sugar of candy skulls;<br />

<strong>en</strong>counters with peanut brittle, filled candies hot off the griddle, meringues<br />

coated with colorful sprinkles, shiny caramel-coated apples on sticks<br />

parading through fairs, multicolored cotton candy, gold<strong>en</strong> coconut<br />

macaroons on their paper base, candy on a stick as hard as a coral reef, white<br />

and pink boiled milk candies, ear-shaped candies that list<strong>en</strong> and sing in our<br />

language, spiral-shaped lollipops, and covered fruit in a still life made for<br />

eternity. Ever pres<strong>en</strong>t, our candies, the glory of Mexico, s<strong>en</strong>d a fri<strong>en</strong>dly wink<br />

to our palette.<br />

■■■<br />

32 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer SWEET LAND — 33

CORN<br />

Maize is the core of the Mexican diet. It is the crop<br />

with most pres<strong>en</strong>ce throughout the country and is the<br />

heart and soul of the milpa.<br />

NIXTAMALIZATION This process prepares the corn for grinding:<br />

Boil<br />

the corn<br />

in limewater.<br />

GRIDDLED<br />

Tortillas<br />

Let<br />

it soak<br />

for 8 hours.<br />

Rinse and<br />

grind to make<br />

masa.<br />

th<br />

world<br />

producer<br />

SINALOA<br />

produces:<br />

FRIED STEAMED BOILED<br />

6%<br />

’ . kg<br />

of the nation’s volume<br />

Tostadas Quesadillas Tamales Atole<br />

is the annual consumption<br />

of tortillas per person<br />

Chemical changes occur in the corn<br />

during nixtamalization. Proteins become<br />

easy to assimilate, the supply of amino acids<br />

increases, and nutrition is <strong>en</strong>hanced with<br />

calcium, iron, and zinc.<br />

THE BASIS<br />

OF OUR CUISINE<br />

THE MILPA IS A CENTURIES-OLD, COMPLEX AGRICULTURAL AND<br />

CULTURAL SYSTEM. THE PLANTS ALL GROW ON THE SAME PLOT,<br />

MAINTAINING FERTILITY OF THE SOIL AND REDUCING EROSION.<br />

MEXICAN MILPA =<br />

corn+ beans + squash + chiles + quelites<br />

Quelite<br />

Cuitlacoche<br />

Cuitlacoche is a fungus that<br />

develops on t<strong>en</strong>der ears of corn<br />

and is considered a culinary delicacy.<br />

CHILE<br />

A herbaceous plant with white or<br />

pink flowers that grows in the milpa.<br />

nd<br />

world producer<br />

of gre<strong>en</strong> chiles<br />

SCOVILLE SCALE<br />

SINALOA<br />

produces:<br />

%<br />

of the nation’s volume<br />

of gre<strong>en</strong> chiles<br />

Some types of peppers and their pung<strong>en</strong>cy:<br />

kg<br />

consumption per<br />

person per year<br />

DOMESTICATED<br />

Chile plants in other<br />

countries have be<strong>en</strong><br />

modified and give<br />

sweet gre<strong>en</strong> peppers.<br />

The burning s<strong>en</strong>sation<br />

and reaction are caused<br />

by capsaicin, a chemical<br />

that stimulates receptors<br />

in skin and mucous<br />

membranes in the mouth.<br />

SALSA ROJA COCIDA =<br />

cooked tomatoes +<br />

cooked fresh chile<br />

de árbol + onion +<br />

garlic + salt<br />

MEXICAN<br />

VARIETIES<br />

Bell pepper<br />

Poblano<br />

Jalapeño<br />

de árbol<br />

Piquín<br />

Habanero<br />

Based on morphological,<br />

adaptable, and g<strong>en</strong>etic<br />

characteristics, corn is<br />

classified in se<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong><br />

racial groups:<br />

BEANS<br />

Conical<br />

Sierra de<br />

Chihuahua<br />

Eight<br />

rows<br />

Chapalote<br />

Beans contain carbohydrates, high protein cont<strong>en</strong>t, fiber, fat, calcium,<br />

iron and vitamins: B-complex, niacin, riboflavin, folic acid, and thiamine.<br />

Beans add nitrog<strong>en</strong> to the milpa and improve the growth of corn and other plants.<br />

Early<br />

Maturing<br />

Tropical<br />

d<strong>en</strong>t<br />

Late<br />

Maturing<br />

FRIJOLES DE LA OLLA =<br />

beans + water + salt + aromatic<br />

herbs (epazote, avocado leaf)<br />

Cuitlacoche<br />

Bean<br />

Corn<br />

Squash<br />

Squash blossom<br />

Chile<br />

Units on 0 From 1,000<br />

the Scoville<br />

Heat Scale<br />

to 2,000<br />

SQUASH<br />

From 2,500<br />

to 10,000<br />

From 10,000<br />

to 30,000<br />

All the varieties are grown in all the agricultural regions.<br />

Squash grows with corn and beans in the milpa.<br />

From 30,000<br />

to 60,000<br />

These are some of the varieties of the g<strong>en</strong>us Cucurbita of the Cucurbitaceae<br />

family, which also includes watermelon, cantaloupe, and cucumber:<br />

:<br />

From 200,000<br />

to 350,000<br />

th world<br />

producer<br />

. kg<br />

consumption<br />

per person per year<br />

In Mexico four species of beans are commonly raised<br />

Common bean<br />

Butter bean<br />

Runner bean<br />

Tepari bean<br />

APPROXIMATE<br />

COOKING TIME<br />

60 minutes<br />

90 to 120<br />

minutes<br />

ZACATECAS produces:<br />

of the nation’s<br />

% volume<br />

. kg of beans<br />

are consumed per person per year<br />

QUELITES<br />

T<strong>en</strong>der herbs rich in nutritional<br />

cont<strong>en</strong>t: high in fiber, iron, potassium<br />

and vitamins C and D. They grow wild<br />

in and around the milpa.<br />

Squash blossoms<br />

are edible.<br />

species<br />

belonging to differ<strong>en</strong>t botanical<br />

families, many of them <strong>en</strong>demic to Mexico.<br />

Pipiana Chilacayote Kabocha Castile or Winter Squash<br />

Fried or grilled,<br />

The seeds are an<br />

Known as Japanese<br />

The pulp is cooked in a<br />

the seeds are<br />

ingredi<strong>en</strong>t in<br />

squash, it is for<br />

brown sugar syrup to<br />

used in pipián<br />

candy brittle.<br />

the Asian market.<br />

make candied squash<br />

and gre<strong>en</strong> mole.<br />

or calabaza <strong>en</strong> tacha.<br />

PIPIÁN VERDE =<br />

Toasted pumpkin seeds +<br />

tomatillos+ water + lard +<br />

serrano chiles + fried garlic+<br />

cilantro, parsley or epazote<br />

leaves + hoja santa + salt<br />

SONOR A<br />

produces:<br />

%<br />

of the nation's<br />

volume of squash<br />

Zucchini<br />

The t<strong>en</strong>der flesh is eat<strong>en</strong><br />

as a vegetable or as an<br />

ingredi<strong>en</strong>t in stews, salads,<br />

soups, and broths.<br />

Data: Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alim<strong>en</strong>tación (SAGARPA) and the Comisión Nacional para el Conocimi<strong>en</strong>to y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO).<br />

34 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer<br />

the basis of our cuisine — 3 6

GASTRONOMIC REGIONs<br />

<strong>v<strong>en</strong></strong> a <strong>comer</strong><br />

MEXICO’S GASTRONOMY IS RICH IN TRADITIONS AND<br />

EXPERIMENTATION. WE HAVE DIVIDED THE COUNTRY INTO<br />

REGIONS BASED ON SHARED PRODUCTS, INGREDIENTS,<br />

DISHES, AND PRESENTATION.<br />

MAR sea Y and DESIERTO DESert<br />

the<br />

EL northeast<br />

NORESTE<br />

Baja<br />

California Califronia<br />

Sonora<br />

Chihuahua<br />

Coahuila<br />

Nuevo León<br />

Zacatecas<br />

Baja<br />

California Califronia<br />

Sur<br />

Sinaloa<br />

Durango<br />

San Luis Potosí<br />

Tamaulipas<br />

the EL PACÍFICO<br />

c<strong>en</strong>tral<br />

pacific DEL CENTRO coast<br />

Nayarit<br />

Jalisco<br />

Country<br />

CAMPO<br />

and<br />

Y<br />

City<br />

CIUDAD<br />

Aguascali<strong>en</strong>tes<br />

Guanajuato<br />

Querétaro<br />

Colima<br />

Guerrero<br />

State Estado<br />

of de México<br />

Hidalgo<br />

Tlaxcala<br />

Michoacán<br />

Morelos<br />

Ciudad<br />

Mexico de México City<br />

betwe<strong>en</strong><br />

ENTRE<br />

two<br />

DOS<br />

oceans<br />

MARES<br />

the<br />

southeast<br />

el sureste<br />

Puebla<br />

Veracruz<br />

Yucatán<br />

Campeche<br />

Oaxaca<br />

Chiapas<br />

Tabasco<br />

Quintana<br />

Roo

sea and<br />

desert<br />

sea and<br />

desert<br />

baja california / baja california sur /<br />

chihuahua / durango / sinaloa / sonora<br />

38 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer sea and deserT — 39

sea and<br />

desert<br />

THE GEOGRAPHY OF THIS REGION SPANS IMMENSE PLAINS,<br />

CRAGGY SIERRAS, UNINHABITABLE DESERTS, AND COASTS WITH<br />

A SCATTERING OF TOWNS AND VILLAGES. IT HAS A WEALTH OF<br />

CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS AND ENORMOUS BIODIVERSITY.<br />

The Sonora beaches<br />

have tranquil waters<br />

and many days of<br />

sunshine.<br />

from<br />

THE SEA<br />

Along the coastline<br />

of this region<br />

—some 5,455<br />

kilometers—<br />

aquaculture produces<br />

crustaceans,<br />

mollusks,<br />

and tuna fish.<br />

Fertile valleys in Baja California produce Mexico’s best wines. Its<br />

waters cradle the baby whales born there. Cave paintings and<br />

Jesuit missions built three hundred years ago attract visitors from<br />

all corners of the world.<br />

The most important Mexican producers of apples, nuts, and<br />

jalapeño peppers are in Chihuahua. This state is proud of the<br />

archaeological ruins of Paquimé and the Copper Canyon region.<br />

Sonora has a thriving industrial city, Hermosillo, considered<br />

one of the five best Mexican cities to live in; two Magical Towns,<br />

Álamos and Magdal<strong>en</strong>a de Kino; and the Altar Desert, a unesco<br />

biosphere reserve.<br />

Sinaloa’s coastline is bathed by the Pacific; it has broad valleys and<br />

is one of the country’s foremost agricultural producers. Mazatlán<br />

and Topolobampo have the second largest fishing fleet in Mexico.<br />

Birthplace of Pancho Villa and Silvestre Revueltas, Durango is<br />

a colonial gem. It is Mexico’s second gold and silver producer. Its<br />

ideal landscapes have be<strong>en</strong> natural sets for several movies on the<br />

American Wild West. ▲<br />

There is a choice of<br />

marinas in this region<br />

for those sailing the<br />

Pacific by yacht.<br />

Paquimé is one of the<br />

foremost archaeological<br />

zones in northern<br />

Mexico.<br />

The Altar Desert has<br />

extreme temperatures<br />

and fascinating sc<strong>en</strong>ery.<br />

Gray whales in Baja<br />

California Sur.<br />

The Cathedral of<br />

Durango, a monum<strong>en</strong>tal<br />

legacy of New Spain.<br />

The arch of Cabo San<br />

Lucas, headland of Baja<br />

California p<strong>en</strong>insula.<br />

40 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer sea and deserT — 41

sea and<br />

desert<br />

FISH OF<br />

THE DAY<br />

serves 4 | 30 minutes | easy<br />

BAJA<br />

STYLE<br />

TACO<br />

Known as a Fish Taco,<br />

this is one of the<br />

classic preparations<br />

of the region. It is a<br />

flour tortilla topped<br />

with batter-fried<br />

fish, cabbage, and<br />

mayonnaise, usually<br />

served with an array of<br />

bottled salsas.<br />

n<br />

INGREDIENTS<br />

Ground dried chiles:<br />

2 guajillo chiles<br />

2 chiles de árbol<br />

2 ancho chiles<br />

2 cascabel chiles<br />

2 morita chiles<br />

2 chipotle chiles, dried<br />

Dried garlic<br />

Natural salt from San Felipe, Baja<br />

California<br />

Fish:<br />

12 tomatillos (gre<strong>en</strong> tomatoes),<br />

cubed<br />

4 tablespoons onion, chopped<br />

2 tablespoons gre<strong>en</strong> chile,<br />

chopped<br />

Fresh coriander leaves<br />

Olive oil<br />

Sherry vinegar<br />

Ground black pepper<br />

4 fresh loin-cut rockot, with skin<br />

(200 grams each)<br />

Ground fine herbs<br />

2 tortillas, toasted and crushed<br />

4 tablespoons dry cheese<br />

2 cups beans, mashed and<br />

refried in lard<br />

PREPARATION<br />

Ground dried chiles:<br />

Discard the veins from the chiles.<br />

Grind them to a powder, add garlic<br />

and salt; set aside.<br />

Fish:<br />

Mix the gre<strong>en</strong> tomatoes, onion,<br />

gre<strong>en</strong> chile and coriander in a<br />

bowl with a dribble of olive oil and<br />

vinegar, salt and pepper. Set aside.<br />

Season the rockot fish with salt,<br />

ground dried chiles, and fine herbs.<br />

Fry the fish in olive oil starting with<br />

skin side down<br />

Add the tortilla and cheese to the<br />

gre<strong>en</strong> tomato salad. Mix well.<br />

Serve the fish with the hot refried<br />

beans and gre<strong>en</strong> tomato salad.<br />

BENITO<br />

MOLINA AND<br />

SOLANGE<br />

MURIS<br />

42 — V<strong>en</strong> a Comer sea and deserT — 43

sea and<br />

desert<br />

A Fusion of<br />

Traditions<br />

SALT<br />

n jair téllez<br />

THE SIERRAS, DESERTS, FERTILE<br />

VALLEYS, AND THE SWEEPING<br />

COASTLINES OF THE PACIFIC<br />

AND SEA OF CORTEZ HAVE<br />

PROVIDED OPPORTUNITIES FOR<br />

THE INHABITANTS OF THIS REGION<br />

TO EXCEL IN MINING, FORESTRY,<br />

AGRICULTURE, AND FISHING.<br />

An ess<strong>en</strong>tial<br />

seasoning.<br />

In Mexico salt is<br />

produced at Guerrero<br />

Negro and San Felipe<br />

in Baja California;<br />

Cuyutlán, Colima;<br />

Salina Cruz, Oaxaca;<br />

and Celestún, Yucatán.<br />

In fact, the exceptionally long shoreline<br />

accounts for the abundance of seafood in<br />

the region’s gastronomy, while the sprawling<br />

plains in Sonora, Chihuahua, and Durango<br />

are the home of cattle ranches that dot the<br />

vast landscape.<br />

There are imm<strong>en</strong>se fields of grains,<br />

vegetables, and fruit for drying. By way of<br />

example, the fields in Sinaloa alone produce<br />

almost 40 perc<strong>en</strong>t of the tomatoes consumed<br />

in Mexico. In neighboring Durango, beans<br />

and corn are major crops.<br />

Sonora rates first place nationwide in<br />

the production of grapes, potatoes, and<br />

asparagus. Mexico is supplied with thousands<br />

of tons of gre<strong>en</strong> chiles, apples, and nuts from<br />

Chihuahua. Ours is an auth<strong>en</strong>tic surf and turf<br />

culinary success.<br />

The distance from the cultures of C<strong>en</strong>tral<br />

Mexico is se<strong>en</strong> in the distinct cuisine of the<br />

Salt works at Guerrero<br />

Negro, Baja California<br />

Sur.<br />

A chef at Restaurante<br />

Manzanilla in Ens<strong>en</strong>ada.<br />

A meat, avocado, and<br />

fish dish at Tras Lomita<br />

in Valle de Guadalupe.<br />

Internationally<br />

r<strong>en</strong>owned lobster tacos<br />

at Puerto Nuevo in<br />

Rosarito.<br />