Army - Stimulating Simulation

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

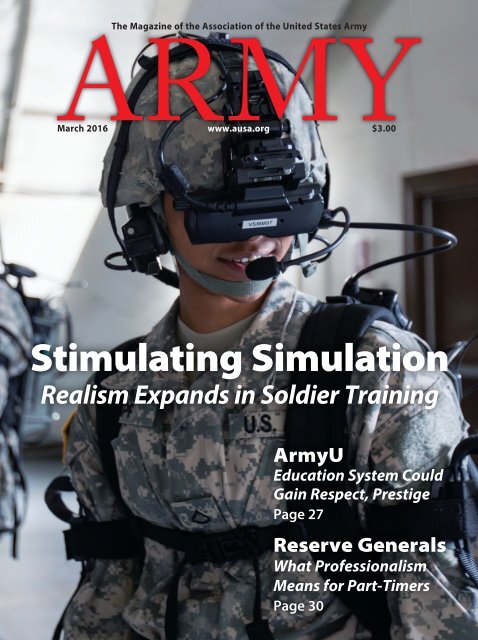

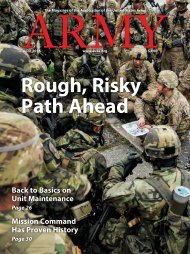

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

ARMY<br />

March 2016 www.ausa.org $3.00<br />

<strong>Stimulating</strong> <strong>Simulation</strong><br />

Realism Expands in Soldier Training<br />

<strong>Army</strong>U<br />

Education System Could<br />

Gain Respect, Prestige<br />

Page 27<br />

Reserve Generals<br />

What Professionalism<br />

Means for Part-Timers<br />

Page 30

THIS CONNECTED.<br />

ONLY CHINOOK.<br />

The CH-47F Chinook is the world standard in heavy-lift rotorcraft, delivering unmatched multi-mission<br />

capability. More powerful than ever and featuring advanced flight controls and a fully integrated digital<br />

cockpit, the CH-47F performs under the most challenging conditions: high altitude, adverse weather,<br />

night or day. So whether the mission is transport of troops and equipment, special ops, search and rescue,<br />

or delivering disaster relief, there’s only one that does it all. Only Chinook.

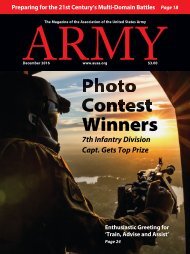

ARMY<br />

The Magazine of the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong><br />

March 2016 www.ausa.org Vol. 66, No. 3<br />

DEPARTMENTS<br />

LETTERS....................................................3<br />

SEVEN QUESTIONS ..................................5<br />

WASHINGTON REPORT ...........................7<br />

NEWS CALL ..............................................9<br />

FRONT & CENTER<br />

The Risk of Another Unsuccessful War<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.<br />

Page 13<br />

Definition of ‘Decisive’<br />

Depends on Context<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.<br />

Page 14<br />

Refugees Display Courage<br />

To Move Forward<br />

By Emma Sky<br />

Page 16<br />

Draft a Bad Idea, With<br />

Or Without Women<br />

By Lt. Col. James Jay Carafano, USA Ret.<br />

Page 17<br />

Bond of Brothers: Infantrymen<br />

Stand Alone but Are Uniquely United<br />

By Col. Keith Nightingale, USA Ret.<br />

Page 19<br />

Millennials: Understanding This<br />

Generation and the Military<br />

By Capt. David Dixon<br />

Page 21<br />

In Mideast Conflicts, at What<br />

Price Victory?<br />

By Lt. Col. Thomas D. Morgan, USA Ret.<br />

Page 22<br />

HE’S THE ARMY......................................26<br />

THE OUTPOST........................................57<br />

SOLDIER ARMED....................................59<br />

HISTORICALLY SPEAKING.....................61<br />

SUSTAINING MEMBER PROFILE ...........64<br />

REVIEWS.................................................65<br />

FINAL SHOT ...........................................72<br />

ON THE COVER<br />

FEATURES<br />

<strong>Army</strong> University: Will Education System<br />

Earn Prestige With Improvements<br />

And a New Name?<br />

By Rick Maze<br />

<strong>Army</strong> University is an ambitious plan to<br />

boost the quality and respect of the<br />

service’s expansive professional education<br />

network with symbolic and substantive<br />

changes. Page 27<br />

Reserve Component Generals: True Professionals<br />

By Brig. Gen. Raymond E. Bell Jr., USA Ret.<br />

General officers of the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Reserve and<br />

<strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard have<br />

successfully<br />

served for<br />

extended<br />

periods on<br />

active duty in an<br />

array of challenging<br />

positions, including<br />

combat. Page 30<br />

<strong>Stimulating</strong> <strong>Simulation</strong>:<br />

Technology Advances and<br />

Upgrades Boost Realism in<br />

Soldier Training<br />

By Scott R. Gourley<br />

With simulation technologies a<br />

ubiquitous element of modern life, it’s<br />

not surprising that today’s soldiers are<br />

encountering the expanded use of<br />

simulation technologies across the<br />

military experience. Page 36<br />

Cover Photo: Pfc. Shante Sapp, Headquarters<br />

and Headquarters Company,<br />

35th Engineer Brigade, Missouri <strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard, uses the Dismounted Soldier<br />

Training System during a virtual training<br />

simulation at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo.<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Pfc. Samantha J. Whitehead<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 1

Germany Committed to Common Defense<br />

By Lt. Gen. Jorg Vollmer<br />

The German <strong>Army</strong> chief of staff describes how and why<br />

his country is fully committed to NATO and the<br />

common defense of Germany’s partners. Page 32<br />

32<br />

40<br />

12-Step Plan for Curing a Toxic Team<br />

By Keith H. Ferguson<br />

A toxic team is a group of people who<br />

conspire to work against the direction<br />

desired by leadership. The first step<br />

toward fixing a toxic team is to admit the<br />

problem exists. Page 40<br />

For Brain-Injured Vets,<br />

COMPASS Offers Direction<br />

By Mitch Mirkin<br />

A VA research program called Community<br />

Participation through Self-Efficacy Skills<br />

Development, or COMPASS, is aiding<br />

veterans with brain injuries by teaching<br />

them skills that help them manage their<br />

condition. Page 43<br />

Peer Pressure: Attorney Evaluation<br />

System Might Benefit All Officers<br />

By Col. William M. Connor<br />

An <strong>Army</strong> Reserve officer who is an attorney<br />

in civilian life describes how the legal<br />

profession’s system of peer evaluation<br />

offers an efficient, fair and equitable<br />

alternative for military use. Page 47<br />

47<br />

43<br />

Facebook Embedded in Family Life<br />

By Rebecca Alwine<br />

Military families use Facebook for myriad reasons,<br />

including staying in touch with family and friends,<br />

obtaining up-to-the minute news, and gathering<br />

information to help with transitions and moves.<br />

Page 52<br />

52<br />

Counseling Can Uncover Oppressive Climate<br />

By Capt. Gary M. Klein and 1st Lt. Brock J. Young<br />

Regular counseling not only builds trust but can also<br />

uncover command climate issues. Page 54<br />

54<br />

49<br />

Reading: The Key to<br />

Critical Thinking<br />

By Lt. Col. C. Richard Nelson, USA Ret.<br />

As part of the process of<br />

connecting ends and means,<br />

<strong>Army</strong> leaders must be broadly<br />

educated and read accordingly—<br />

beyond briefing books prepared<br />

by their staffs. Page 49<br />

2 ARMY ■ March 2016

Letters<br />

A Fight We Can’t Afford to Lose<br />

■ Usually, in boxing, a one-two punch<br />

is good for a knockout, but the one-twothree<br />

punch in the first three articles in<br />

the Front & Center section of the January<br />

issue should certainly foster a wakeup.<br />

Retired Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen<br />

(“America: Step Up, Wake Up, Wise<br />

Up”), Emma Sky (“What Lessons<br />

Should We Take From the Iraq War?”)<br />

and retired Lt. Col. James Jay Carafano<br />

(“Syria Operations Sending All the<br />

Wrong Signals”) put in perspective the<br />

absolutely critical situation that faces<br />

our country, the dangers thereof, and<br />

the tough road to recovery. Such discussions<br />

are long overdue and, unfortunately,<br />

muted.<br />

I have been around for 93 years and<br />

have seen the results of our lack of preparedness<br />

in two world wars, and I do<br />

not want it to happen again. You have<br />

made a good start with these splendid<br />

articles, but the bugle must be sounded<br />

louder. Please take a deep breath before<br />

the next issue.<br />

Maj. Gen. Chet McKeen, USA Ret.<br />

Fort Worth, Texas<br />

Recruiting Saw Many Changes<br />

■ In his January article, “Let’s Solve<br />

the <strong>Army</strong>’s Recruiting Challenges,” retired<br />

Col. Bob Phillips omits mention of<br />

a third advertising campaign that preceded<br />

Maj. Gen. Maxwell R. Thurman’s<br />

arrival as head of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Recruiting<br />

Command. Recruiting always gets<br />

tougher when the economy improves and<br />

inevitably, advertising is looked to as a<br />

partial solution. I was deputy director of<br />

advertising and sales promotion for Recruiting<br />

Command from June 1973 until<br />

January 1993 and believe knowledge of<br />

earlier hits and misses can be helpful to<br />

those now in charge of using advertising<br />

to help provide the strength.<br />

The advertising program effectively<br />

began in 1971 with a campaign designed<br />

to make young people rethink traditional<br />

objections to <strong>Army</strong> life. The slogan “Today’s<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Wants to Join You” suggested<br />

a kindlier welcoming than the average<br />

new recruit was liable to encounter,<br />

and aspirations of the <strong>Army</strong>’s Modern<br />

Volunteer <strong>Army</strong> office that were never<br />

widely implemented were publicized.<br />

Old soldiers saw it as a threat to good<br />

order and discipline. Civilian critics wondered<br />

if it was a misrepresentation. It was<br />

pulled after two years and replaced with<br />

“Join the People Who’ve Joined the<br />

<strong>Army</strong>,” which ran until 1978. That it did<br />

so without controversy was mostly because<br />

lessons learned with the earlier<br />

campaign had been taken to heart by the<br />

advertising agency and <strong>Army</strong> officials responsible<br />

for approving the ads, but also<br />

because it was less visible. “Today’s <strong>Army</strong>”<br />

had burst on the scene with a major television<br />

buy, but Congress kept <strong>Army</strong> advertising<br />

off TV, the most intrusive (and<br />

effective) medium, from 1973 to 1978.<br />

Then, <strong>Army</strong> recruiting was put on the<br />

defensive by a congressional staff report<br />

containing quotes by soldiers in Europe<br />

alleging lies by recruiters and misleading<br />

impressions in the advertising. The contract<br />

advertising agency, N.W. Ayer, addressed<br />

the problem by creating the<br />

“This is the <strong>Army</strong>” campaign, which<br />

promised a “warts and all” view of <strong>Army</strong><br />

service. This approach was welcomed in<br />

the Pentagon and the halls of Congress<br />

but found few fans among struggling recruiters,<br />

who observed that some of the<br />

“warts” were mainly helpful to their<br />

competitors in the other services.<br />

This was the advertising that Thurman<br />

found when he arrived at Recruiting<br />

Command. In an early meeting, he<br />

told agency executives he wanted it replaced<br />

with something more upbeat to<br />

match the many changes in recruiting he<br />

was about to introduce. They outlined,<br />

and he approved, an approach that entailed<br />

best industry practices and catered<br />

to his formidable analytical demands.<br />

Unlike his predecessors in command, he<br />

took an intense interest in the yearlong<br />

process, reviewing progress in grueling<br />

monthly sessions and educating the<br />

agency in important aspects of the “product,”<br />

notably the <strong>Army</strong> modernization<br />

program that would make credible the<br />

copy line: “In the <strong>Army</strong>, the Cavalry flies,<br />

the Infantry rides, and the Artillery can<br />

hit a fly in the eye 15 miles away.”<br />

The somewhat dispirited recruiters<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> National Guard/1st Lt. Jessica Donnelly<br />

Members of the South Carolina <strong>Army</strong> National Guard graduate from the Recruit Sustainment Program.<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 3

Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan, USA Ret.<br />

President and CEO, AUSA<br />

Lt. Gen. Guy C. Swan III, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Education, AUSA<br />

Rick Maze<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Liz Rathbun Managing Editor<br />

Joseph L. Broderick Art Director<br />

Ferdinand H. Thomas II Sr. Staff Writer<br />

Toni Eugene<br />

Associate Editor<br />

Christopher Wright Production Artist<br />

Laura Stassi Assistant Managing Editor<br />

Thomas B. Spincic Assistant Editor<br />

Contributing Editors<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret.;<br />

Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, USA Ret.; Lt.<br />

Gen. Daniel P. Bolger, USA Ret.; and<br />

Brig. Gen. John S. Brown, USA Ret.<br />

Contributing Writers<br />

Scott R. Gourley and Rebecca Alwine<br />

Lt. Gen. Jerry L. Sinn, USA Ret.<br />

Vice President, Finance and<br />

Administration, AUSA<br />

Desiree Hurlocker<br />

Advertising Production and<br />

Fulfillment Manager<br />

ARMY is a professional journal devoted to the advancement<br />

of the military arts and sciences and representing the in terests<br />

of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>. Copyright©2016, by the Association of<br />

the United States <strong>Army</strong>. ■ ARTICLES appearing in<br />

ARMY do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the officers or<br />

members of the Council of Trustees of AUSA, or its editors.<br />

Articles are expressions of personal opin ion and should not<br />

be interpreted as reflecting the official opinion of the Department<br />

of Defense nor of any branch, command, installation<br />

or agency of the Department of Defense. The magazine<br />

assumes no responsibility for any unsolicited material.<br />

■ ADVERTISING. Neither ARMY, nor its pub lisher,<br />

the Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>, makes any representations,<br />

warranties or endorsements as to the truth and<br />

accuracy of the advertisements appearing herein, and no<br />

such representations, warranties or endorsements should be<br />

implied or inferred from the appearance of the advertisements<br />

in the publication. The advertisers are solely responsible<br />

for the contents of such advertisements.<br />

■ RATES. Individual membership fees payable in advance<br />

are $30 for two years, $50 for five years, and $300 for Life<br />

Membership, of which $9 is allocated for a subscription to<br />

ARMY magazine. A discounted rate of $10 for two years is<br />

available to members in the ranks of E-1 through E-4, and for<br />

service academy and ROTC cadets and OCS candidates. Single<br />

copies of the magazine are $3, except for a $20 cost for the<br />

special October Green Book. More information is available at<br />

our website www.ausa.org; or by emailing membersupport<br />

@ausa.org, phoning 855-246-6269, or mailing Fulfillment<br />

Manager, P.O. Box 101560, Arlington, VA 22210-0860.<br />

got a preview of the new campaign in<br />

mid-December 1980, a few weeks before<br />

the first commercials aired, in the form<br />

of a short film that began with Thurman<br />

outlining his vision for the recruiting future<br />

and proceeding to display the first<br />

two TV spots. They tolerated the lecture<br />

and applauded the commercials. Spirits<br />

all around were lifted when jingle writer<br />

Jake Holmes was heard singing the little<br />

anthem he had composed, scored and<br />

recorded over a weekend after the winning<br />

slogan had been chosen.<br />

“Be All You Can Be” evolved over the<br />

next 20 years—a long run for an ad campaign—and<br />

played an important part in<br />

recruiting success. In its millennial issue,<br />

Advertising Age ranked it No. 18 among<br />

the best 100 ad campaigns of the 20th<br />

century.<br />

But the <strong>Army</strong> is given a large advertising<br />

budget for finding the very best way<br />

to convince young people they should<br />

meet with a recruiter. That must remain<br />

the main focus of the effort.<br />

Capt. Thomas W. Evans,<br />

U.S. Naval Reserve retired<br />

Mundelein, Ill.<br />

AUSA FAX NUMBERS<br />

ARMY magazine welcomes letters to<br />

the editor. Short letters are more<br />

likely to be published, and all letters<br />

may be edited for reasons of style,<br />

accuracy or space limitations. Letters<br />

should be exclusive to ARMY magazine.<br />

All letters must include the<br />

writer’s full name, address and daytime<br />

telephone num ber. The volume<br />

of letters we receive makes individual<br />

acknowledgment impossible. Please<br />

send letters to The Editor, ARMY magazine,<br />

AUSA, 2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington,<br />

VA 22201. Letters may also<br />

be faxed to 703- 841-3505 or sent via<br />

email to armymag@ausa.org.<br />

Take Mideast Warnings to Heart<br />

■ It was interesting to find the sharp<br />

contrast in the Middle East perspectives<br />

of Emma Sky, director of Yale World<br />

Fellows, and retired Lt. Col. James Jay<br />

Carafano, a Heritage Foundation vice<br />

president, in the January issue of ARMY<br />

magazine.<br />

In “What Lessons Should We Take<br />

From the Iraq War?” Sky stated that she<br />

was opposed to the 2003 Iraq War and<br />

then without specifying blame, succinctly<br />

wrote a factual sequence of the events<br />

and consequences. She then provided insightful<br />

suggestions that are conducive to<br />

discussion and reflection.<br />

Carafano wrote an exceedingly critical<br />

critique of U.S. involvement in the Middle<br />

East in “Syria Operations Sending<br />

All the Wrong Signals.” The focus and<br />

target of his criticism was specific, with<br />

over a dozen references to President<br />

Barack Obama and “the administration.”<br />

Carafano referenced the leadership styles<br />

of eight presidents, starting with George<br />

Washington and ending with Ronald<br />

Reagan, but neglected to mention the<br />

administration that passed on to Obama<br />

two active wars and an economy that was<br />

in the greatest recession since the Great<br />

Depression.<br />

It is a complex world. It is my hope<br />

that all commanders in chief, in concert<br />

with the American people, will take<br />

Sky’s warning to heart: “If we don’t learn<br />

anything from the Iraq War, then all<br />

that sacrifice, all that loss of blood and<br />

treasure, will have been for nothing.”<br />

Col. Tyrone L. Steen, AUS Ret.<br />

Colorado Springs, Colo.<br />

ADVERTISING. Information and rates available<br />

from AUSA’s Advertising Production Manager or:<br />

Andrea Guarnero<br />

Mohanna Sales Representatives<br />

305 W. Spring Creek Parkway<br />

Bldg. C-101, Plano, TX 75023<br />

972-596-8777<br />

Email: andreag@mohanna.com<br />

ARMY (ISSN 0004-2455), published monthly. Vol. 66, No. 3.<br />

Publication offices: Association of the United States <strong>Army</strong>,<br />

2425 Wilson Blvd., Arlington, VA 22201-3326, 703-841-<br />

4300, FAX: 703-841-3505, email: armymag@ausa.org. Visit<br />

AUSA’s website at www.ausa.org. Periodicals postage paid at<br />

Arlington, Va., and at additional mailing office.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to ARMY Magazine,<br />

Box 101560, Arlington, VA 22210-0860.<br />

703-236-2929<br />

Institute of Land<br />

Warfare,<br />

Senior Fellows<br />

703-243-2589<br />

Industry Affairs<br />

703-841-3505<br />

ARMY Magazine,<br />

AUSA News,<br />

Communications<br />

703-841-1442<br />

Administrative<br />

Services<br />

703-841-1050<br />

Executive Office<br />

703-841-5101<br />

Information<br />

Technology<br />

703-236-2927<br />

Regional Activities,<br />

NCO/Soldier<br />

Programs<br />

703-525-9039<br />

Finance,<br />

Accounting,<br />

Government<br />

Affairs<br />

703-236-2926<br />

Education,<br />

Family<br />

Programs<br />

703-841-7570<br />

Marketing,<br />

Advertising,<br />

Insurance<br />

4 ARMY ■ March 2016

Seven Questions<br />

Scarce Resource for Soldiers: Good Night’s Sleep<br />

Lt. Col. Ingrid Lim is the sleep lead for the <strong>Army</strong>’s Performance<br />

Triad Division, System for Health Directorate.<br />

1. When did the <strong>Army</strong> start studying soldiers’ sleep, and why?<br />

There is a long tradition of sleep research going back to the<br />

1950s at the Walter Reed <strong>Army</strong> Institute of Research looking<br />

at sleep deprivation, fatigue modeling,<br />

and the impact of various patterns of<br />

sleep restriction on cognitive performance.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> recognized that sleep<br />

is a valuable resource. Scientific studies<br />

and tools are required to optimize soldiers’<br />

performance.<br />

The current interest in studying clinical<br />

sleep disorders with soldiers came to<br />

the forefront recently for several reasons.<br />

Sleep is markedly disturbed from wounds<br />

sustained in combat such as traumatic<br />

brain injuries, post-traumatic stress disorder,<br />

and orthopedic injuries with associated<br />

pain. Further, the operational tempo<br />

of combat operations was such that soldiers<br />

frequently obtained insufficient<br />

sleep and lacked standard education on<br />

sleep management and countermeasures.<br />

2. What have been some of the major<br />

findings about soldiers’ sleep habits?<br />

Overall, it is fairly common for soldiers to forgo sleep for military<br />

duties, poor sleep practices, or the inappropriate perception<br />

that sleeping is for lazy or weak individuals.<br />

Texting, watching television or using the computer before<br />

bed, or not having a bedtime routine, add to the challenges of<br />

obtaining healthy sleep. Excessive caffeine intake from energy<br />

drinks, sodas and coffee also plays a role. … Soldiers who perform<br />

non-daytime duties may choose to spend time with their<br />

family instead of sleeping.<br />

3. What methods does the <strong>Army</strong> use to study sleep?<br />

Traditional methods used in a sleep lab include observation;<br />

actigraphy [continuous monitoring by means of a body-worn<br />

device, often on the wrist] and polysomnography [recording of<br />

brain waves, oxygen levels in the blood, heart rate and breathing,<br />

and eye and leg movements]. Sleep is also studied based on<br />

self-report questionnaires regarding various aspects such as<br />

sleep quality and duration.<br />

4. What are some of the next steps planned as a result of the<br />

findings?<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Medical Research and Materiel Command, the<br />

Walter Reed <strong>Army</strong> Institute of Research, and the Biotechnology<br />

High Performance Computing Software Applications Institute<br />

are developing tools for individual soldiers and units to<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Lt. Col. Ingrid Lim<br />

help them better manage fatigue and implement sleep-management<br />

strategies down to the squad level. The <strong>Army</strong> is also<br />

determining ways to prevent sleep loss, identify sleep problems<br />

and sleep disorders, and optimally treat and manage sleep disorders<br />

in soldiers.<br />

Despite increased awareness regarding the importance of<br />

sleep, it is clear that further education is<br />

required on the health and performance<br />

benefits of sleep—education that will lead<br />

to recommendations for <strong>Army</strong> policies<br />

that establish appropriate guidelines for<br />

sleep duration in soldiers, as well as safetyrelated<br />

policies when adequate sleep is not<br />

obtained.<br />

5. What have the Iraq and Afghanistan<br />

wars shown us about sleep?<br />

The wars have demonstrated the effectiveness<br />

of sleep-management planning.<br />

When soldiers are provided with guidance<br />

on appropriate sleep management,<br />

they tend to get better sleep and perform<br />

their military duties better. A soldier who<br />

sleeps well is more resilient.<br />

6. What partnerships has the <strong>Army</strong><br />

formed in the study of sleep?<br />

We currently have several partnerships<br />

both within and outside of the <strong>Army</strong>,<br />

and are working to proliferate sleep knowledge that is intuitively<br />

easy to access. The Office of the Surgeon General recently<br />

hosted a Sleep Summit with representation from major<br />

<strong>Army</strong> commands; civilian and <strong>Army</strong> scientists; clinicians; and<br />

academics from Harvard University, the University of Pittsburgh,<br />

the University of Virginia and RAND Corp. This collection<br />

of renowned sleep experts not only identified specific<br />

sleep priorities within the <strong>Army</strong> but developed a way forward to<br />

accomplish these priorities.<br />

7. Can you predict what sleep science will look like in the<br />

coming years?<br />

As Yogi Berra once observed, “Predictions are hard, especially<br />

about the future.” It is likely that the future of sleep research<br />

will include an increased focus on the long-term effects of<br />

sleep loss on health and an ever-expanding array of issues such<br />

as post-traumatic stress disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer<br />

and autoimmune disorders; the short-term negative consequences<br />

of sleep loss and the positive effects of sleep enhancement<br />

and/or supplementation on resilience to both psychological<br />

and physical trauma; and the increased development and<br />

improvement of technologies that can maximize soldiers’ alertness,<br />

performance, health and well-being.<br />

—Thomas B. Spincic<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 5

Washington Report<br />

Commission: Rough Terrain Ahead for <strong>Army</strong><br />

The final report of the National Commission on the Future<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong> fuels a growing concern in Washington, D.C.,<br />

that the <strong>Army</strong> and the nation could be in trouble and without<br />

any short-term fixes.<br />

“Even with budgets permitting a force of 980,000, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

faces significant shortfalls,” the report says, adding that current<br />

and planned “aviation assets cannot meet<br />

expected wartime capacity requirements.”<br />

There are no short-range air defense<br />

battalions in the Regular <strong>Army</strong>, and many<br />

assets in the National Guard are dedicated<br />

to protecting the nation’s capital, “leaving<br />

precious little capability for other global<br />

contingencies, including high-threat areas<br />

in northeast Asia, southwest Asia, Eastern<br />

Europe or the Baltics,” the report says.<br />

Shortfalls also exist in military police,<br />

field artillery, fuel distribution, water purification,<br />

missile defense, tactical mobility<br />

and watercraft; and with chemical, biological,<br />

radiological and nuclear capabilities.<br />

“Remedying these shortfalls within a<br />

980,000-soldier <strong>Army</strong> will require hard<br />

choices and difficult trade-offs,” the report says.<br />

Retired <strong>Army</strong> Gen. Gordon R. Sullivan, president and CEO<br />

of the Association of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>, said he believes the report<br />

“provides a rare opportunity to address risky capability<br />

shortfalls, reinforce the Total Force concept, and convince a<br />

skeptical Congress and American public there are limits to<br />

how small the <strong>Army</strong> should shrink.”<br />

The commission, headed by retired Gen. Carter F. Ham,<br />

was established by the National Defense Authorization Act for<br />

Fiscal Year 2015. It was tasked with examining the size and<br />

force structure of the <strong>Army</strong>’s active and reserve components.<br />

For political and budgetary reasons, the report says it is “unlikely,<br />

at least for the next few years,” for the <strong>Army</strong> to have<br />

combined active, <strong>Army</strong> Guard and <strong>Army</strong> Reserve forces of<br />

more than 980,000 soldiers. The smart course may be to take<br />

two infantry brigade combat teams out of the Regular <strong>Army</strong> to<br />

free active-duty space for the expanded manning of aviation,<br />

short-range air defense and other capabilities in short supply.<br />

Shifting soldiers doesn’t solve all of the problems, the report<br />

says. “Even if end-strength constraints can be met, the <strong>Army</strong><br />

will need significant additional funding,” it says. The <strong>Army</strong> will<br />

be in a better position to ask for and receive money if it works<br />

with DoD, the White House and Congress on cost-cutting initiatives<br />

to reduce redundancies and improve efficiency. These efforts<br />

“will not be enough” to pay for everything. “Added funding<br />

will eventually be needed if major shortfalls are to be eliminated.”<br />

The other members of the panel were retired Sgt. Maj. of<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> Raymond F. Chandler III; retired Gens. Larry R.<br />

Ellis and James D. Thurman; retired Lt. Gen. Jack C. Stultz;<br />

Thomas R. Lamont, a former assistant secretary of the <strong>Army</strong>;<br />

Robert F. Hale, a former undersecretary of defense; and<br />

Kathleen H. Hicks of the Center for Strategic and International<br />

Studies.<br />

“Although the commission acknowledges<br />

the impossibility of precisely predicting<br />

the future, the commission is certain<br />

that U.S. leaders will face a variety of simultaneous,<br />

diverse threats to our national interests<br />

from both state and non-state actors<br />

as well as natural and man-made disasters,”<br />

the report says.<br />

The commissioners also warn against any<br />

deeper cuts. A total force of 980,000 uniformed<br />

personnel “is the minimum sufficient<br />

force necessary to meet the challenges<br />

of the future strategic environment,” the report<br />

says, listing six things the <strong>Army</strong> could<br />

emphasize to be better ready to tackle the<br />

unknown:<br />

■ Adaptive and flexible leaders are<br />

needed to respond to new technology and unanticipated enemy<br />

action. “<strong>Army</strong> leaders will need to adapt available capabilities<br />

and technology to unexpected missions,” the report says.<br />

■ Cyber capabilities need to be improved “due to the<br />

<strong>Army</strong>’s increasing reliance on computer networks and the<br />

growth of cyber capabilities by state and non-state actors.”<br />

■ Capabilities need to be expanded for urban warfare and<br />

operations in big cities.<br />

■ Flexible and smaller unit formations are needed for future<br />

operations.<br />

■ Defenses against air, rocket and missile attacks need to be<br />

improved.<br />

■ More investment is needed in “game-changing technologies,”<br />

and also in preparing leaders to know how to exploit the<br />

new technologies to the fullest advantage.<br />

A crucial part of the report deals with relations between the<br />

Regular <strong>Army</strong> and the reserve components, a situation soured<br />

by tight budgets that have caused competition for resources<br />

and attention. The commission has a novel idea for having<br />

everyone get along, proposing a pilot program that would integrate<br />

recruiting of active, <strong>Army</strong> National Guard and <strong>Army</strong><br />

Reserve forces into a single effort. This might result in the<br />

components better understanding each other, and may also<br />

save money.<br />

A tight budget led the <strong>Army</strong> to cancel combat-training rotations;<br />

as a result, four <strong>Army</strong> National Guard units were not<br />

deployed overseas in 2013, the report notes.<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 7

News Call<br />

U.S. Air National Guard/Master Sgt. Toby Valadie<br />

Weather, Events Keep National Guard Busy<br />

From helping people deal with extreme<br />

weather to providing security for<br />

the visiting pope and other special events<br />

in the U.S., 2015 was a busy year for the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> National Guard. And 2016 is<br />

keeping pace.<br />

Extreme weather alone made 2015<br />

the National Guard’s busiest year since<br />

2011, but the start of 2016 suggested it<br />

might equal or even eclipse 2015 in<br />

terms of weather conditions requiring<br />

National Guard assistance, with a historic<br />

blizzard blanketing the mid-Atlantic<br />

states and a shift in the El Nino<br />

weather pattern bringing record rain<br />

and historic flooding to states from California<br />

to Louisiana.<br />

“On average, about 1,500 Guard<br />

members were on duty each day” in 2015,<br />

said Gen. Frank J. Grass, chief of the<br />

National Guard Bureau.<br />

In January, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder<br />

activated his state’s National Guard<br />

to distribute drinking water and filters to<br />

the residents of Flint, a city with a population<br />

of about 100,000. The city had<br />

switched its supply source from Lake<br />

Huron water treated by the Detroit Water<br />

and Sewerage Department to Flint<br />

River water treated at the Flint water<br />

treatment plant. The plant did not add<br />

corrosion-control chemicals to the water<br />

A stuck ambulance gets help from Maryland <strong>Army</strong> National Guard troops during Winter Storm Jonas.<br />

and it was rendered undrinkable when it<br />

was contaminated by lead leaching into<br />

it from pipes and fixtures.<br />

The National Guard manned five distribution<br />

sites at fire stations in Flint,<br />

and was planning to stay active as long as<br />

necessary.<br />

Also in January, Winter Storm Jonas<br />

dropped more than 2 feet of snow and<br />

packed 70 mph wind gusts in the mid-<br />

Atlantic region, closing the federal government<br />

as well as local governments<br />

and hundreds of schools for days. Governors<br />

from 11 states including Georgia,<br />

North Carolina, New York and<br />

New Jersey called up more than 2,200<br />

National Guard personnel. The soldiers<br />

transported medical patients and<br />

providers and helped transport emergency<br />

responders to their calls.<br />

The year 2015 began with snowstorms<br />

smothering the South and Midwest<br />

while Western forests burned to the<br />

ground. Storms raged through Massachusetts,<br />

Virginia and Tennessee. Spring<br />

brought a record fire season in states<br />

from North Dakota to New York, and<br />

more flooding in Texas and Oklahoma.<br />

In September, National Guard units<br />

in New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey<br />

and Washington, D.C., helped provide<br />

security and traffic assistance for Pope<br />

Francis’s visit. National Guard members<br />

from several other states including<br />

West Virginia, Massachusetts, Alaska,<br />

With flooding expected in January, soldiers from<br />

the Louisiana <strong>Army</strong> National Guard repair a levee.<br />

Maryland <strong>Army</strong> National Guard<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 9

Kentucky, Delaware, Nebraska, Maryland<br />

and California also supported the<br />

mission.<br />

As 2015 ended, National Guard soldiers<br />

from New Mexico to Missouri<br />

were still cleaning up snow, transporting<br />

patients to doctors, and fighting flooding.<br />

More than 600 members of the<br />

Missouri National Guard assisted emergency<br />

responders in that state. Then, a<br />

series of record storms dropped snow<br />

and rain on California, sparking flash<br />

floods and mudslides.<br />

The El Nino phenomenon, when the<br />

central Pacific Ocean warms, disrupted<br />

established weather patterns around the<br />

world. Meteorologists have rated the<br />

current El Nino as strong as the one that<br />

occurred in 1997–98, when California<br />

and Southern states were deluged and<br />

the Northern half of the country suffered<br />

record-breaking cold.<br />

Report: Delaying Modernization<br />

Leads to Higher Price Tags<br />

A new report about the affordability of<br />

military modernization programs projects<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> will increase weapons<br />

spending 28 percent by fiscal year 2022,<br />

with an increase in spending on ground<br />

systems but a “sharp reduction” in aircraft.<br />

The Center for Strategic and International<br />

Studies report, by analyst Todd<br />

Harrison, discusses the so-called “bow<br />

wave” effect of constantly delaying weapons<br />

modernization, resulting in the cumulative<br />

price tag slowly rising. “The<br />

modernization bow wave cannot be pushing<br />

into the future indefinitely,” Harrison<br />

warns in “Defense Modernization Plans<br />

Through the 2020s: Addressing the Bow<br />

Wave.” “Difficult choices lie ahead if the<br />

modernization bow wave proves too<br />

steep to climb,” he writes.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> acquisition funding is low because<br />

of the cancellation of the Future<br />

Combat Systems and the Ground Combat<br />

Vehicle, and the winding down of<br />

building MRAPs, Harrison writes. Now,<br />

the <strong>Army</strong> is ramping up funding for five<br />

major vehicle programs over the next five<br />

years and modernizing several communications<br />

systems. The Joint Light Tactical<br />

Vehicle program is the largest program,<br />

with production expected through fiscal<br />

year 2040 at a rate of about 2,200 vehicles<br />

a year.<br />

SoldierSpeak<br />

On Challenges<br />

“I distinctly remember challenging myself to work harder, to be as fast or as<br />

strong or as skilled or as smart as many of you. It was a healthy competition that inspired<br />

me to be better every single day,” said Brig. Gen. Diana M. Holland upon<br />

assuming command as the first female officer to serve as commandant of cadets at<br />

the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y.<br />

On Leading the Pack<br />

“We need resilient, mentally and physically fit soldiers of character who can become<br />

competent, committed, agile and adaptive leaders who can perform for<br />

these cohesive teams of trusted professionals and represent the diversity of America,”<br />

said Deputy Chief of Staff, G-1, Lt. Gen. James C. McConville during a visit<br />

to Fort Leonard Wood, Mo. “Young people want to be on a team that does important<br />

stuff. They’re the type of soldiers we want in our <strong>Army</strong>.”<br />

On Family Role Models<br />

“I want to feel the same pride and responsibility as my father has shown,” said<br />

Kerrigan B. Head as her dad, a 10th Mountain Division chief warrant officer, swore<br />

her in at a Military Entrance Processing Station in Syracuse, N.Y. “I enlisted in the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> out of all the other branches because I’ve already lived the <strong>Army</strong> life since I<br />

was 3 years old, and I have seen what can be offered to me through the work of my<br />

father. I want to continue my education and create my own adventures.”<br />

On Imagination as Secret Ingredient<br />

“I wish I had these dishes in basic” training, said Pvt. Yorby Fernandez, a culinary<br />

specialist with the 145th Maintenance Company, New York <strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard, and a judge in a contest for Hudson Valley high school students to<br />

turn randomly chosen MRE components into creative, tasty meals complete with<br />

drink and dessert. “They did an amazing job,” Fernandez said.<br />

On Being Prepared<br />

“The worst thing you can ever do in any situation is not do anything at all,” said<br />

Spc. Jake Planatscher, a medic with the 705th Military Police Detention Battalion,<br />

Fort Leavenworth, Kan., who was named a “Hero of the Month” for his<br />

contributions to the Joint Regional Correctional Facility for military inmates.<br />

On Helping Neighbors<br />

“What I’ve enjoyed the most is seeing the reactions from the senior citizens and<br />

all veterans we’ve been helping,” said Pfc. Nestor Renteria when the 717th<br />

Brigade Support Battalion, New Mexico <strong>Army</strong> National Guard, based in<br />

Roswell, helped fellow residents and local emergency services recover after a<br />

historic blizzard crippled the town.<br />

On Suicide Intervention<br />

“A person at risk feels like they have nothing to live for,” said Sgt. Charles<br />

Stokes, motor transport operator with the 1st Armored Division, who was recognized<br />

at Fort Bliss, Texas, for successful suicide interventions. “So you have to<br />

help that person find a turning point, a reason to live. You find that from hearing<br />

out their story.”<br />

On Unmanned Aerial Systems<br />

“One of the drawbacks is that UAVs can’t get people to come out because they<br />

can’t see them,” said Chief Warrant Officer 3 Jason Richards, a Kiowa pilot with<br />

the 82nd Airborne Division, during the helicopter’s last rotation at Fort Polk, La.<br />

“They see us and we scare them, and that forces them to come out and fight, then<br />

we shoot them.”<br />

10 ARMY ■ March 2016

GENERAL OFFICER CHANGES*<br />

Maj. Gen. M.A.<br />

Bills from CG, 1st<br />

Cavalry Div., Fort<br />

Hood, Texas, to<br />

Asst. CoS, C-3/J-3,<br />

UNC/CFC/USFK,<br />

ROK.<br />

Maj. Gen. J.C.<br />

Thomson III from<br />

Cmdt. of Cadets,<br />

USMA, West Point,<br />

N.Y., to CG, 1st<br />

Cavalry Div., Fort<br />

Hood.<br />

Brigadier Generals: P. Bontrager from Cmdr.,<br />

TAAC-S, RSM, NATO, OFS, Afghanistan, to Dep.<br />

CG, 10th Mountain Div. (Light) and Acting Senior<br />

Cmdr., Fort Drum, N.Y.; D.M. Holland<br />

from Dep. CG, Spt., 10th Mountain Div., Fort<br />

Drum, to Cmdr. of Cadets, USMA.<br />

■ CG—Commanding General; CoS—Chief of<br />

Staff; OFS—Operation Freedom’s Sentinel;<br />

ROK—Republic of Korea; RSM—Resolute Support<br />

Mission; Spt.—Support; TAAC-S—Train Advise<br />

Assist Cmd.-South; UNC/CFC/USFK—United<br />

Nations Cmd./Combined Forces Cmd./U.S. Forces<br />

Korea; USMA—U.S. Military Academy.<br />

*Assignments to general officer slots announced<br />

by the General Officer Management Office, Department<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong>. Some officers are listed at<br />

the grade to which they are nominated, promotable<br />

or eligible to be frocked. The reporting<br />

dates for some officers may not yet be determined.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Fatalities in Iraq<br />

The following U.S. <strong>Army</strong> soldier<br />

died supporting Operation Inherent<br />

Resolve from Jan. 1-31. His<br />

name was released through DoD;<br />

his family has been notified.<br />

Sgt. Joseph F. Stifter, 30<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Fatalities in Afghanistan<br />

The following U.S. <strong>Army</strong> soldier<br />

died supporting Operation Freedom’s<br />

Sentinel from Jan. 1–31.<br />

His name was released through<br />

DoD; his family has been notified.<br />

Staff Sgt. Matthew Q. McClintock,<br />

30<br />

Also in development is the Armored<br />

Multi-Purpose Vehicle, a replacement<br />

for the Paladin 155 mm self-propelled<br />

artillery, upgrading Abrams tanks, and<br />

improvements in Bradley Infantry Fighting<br />

Vehicles. “Together these programs<br />

will increase funding for the <strong>Army</strong>’s major<br />

ground systems learning threefold between<br />

FY 2015 and FY 2021,” Harrison<br />

writes.<br />

Aviation funding is declining, Harrison<br />

says, because several major aircraft<br />

programs are ending, including the MQ-<br />

1C Grey Eagle, CH-47F Chinook,<br />

AH-64E Apache and UH-60M Black<br />

Hawk. The <strong>Army</strong> is still spending on<br />

aviation procurement, with upgraded<br />

turbine engines for the Apache and<br />

Black Hawk helicopters and development<br />

of vertical lift helicopters.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> is just a small part of acquisition<br />

expansion, Harrison says, noting<br />

there are 120 major programs underway<br />

or planned to start in the next 15 years,<br />

not including classified programs.<br />

‘Health of the Force’ Report<br />

Prescribes Performance Progress<br />

Active-duty soldiers could greatly improve<br />

their personal performance—and<br />

with it the <strong>Army</strong>’s readiness—by getting<br />

more sleep, increasing their physical activity,<br />

and eating healthier foods, according<br />

to the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Medical Command.<br />

The first-of-its-kind report, called<br />

Health of the Force, tracks chronic disease,<br />

obesity, tobacco use and numerous other<br />

health factors as well as the Performance<br />

Triad of sleep, physical activity and nutrition<br />

to create a snapshot of soldiers’<br />

health across 30 major installations.<br />

The <strong>Army</strong> focuses on the Performance<br />

Triad, or P3, as a way to proactively promote<br />

health and prevention instead of<br />

dealing with chronic problems that develop<br />

over time. Given 100 as a perfect<br />

P3 score, the <strong>Army</strong> targeted 85 as an acceptable<br />

score for soldiers. No installation<br />

made the cut. They averaged 67 in<br />

sleep, 81 in activity, and 69 in nutrition.<br />

The lack of any one of the three critical<br />

factors has a major impact on <strong>Army</strong><br />

readiness. More than a third of newly accessioned<br />

soldiers fail to complete their<br />

first enlistment term. About 17 percent<br />

of active-duty soldiers cannot be medically<br />

ready to deploy with three days’<br />

notice; simple failure to keep up with<br />

dental and medical checkups accounts<br />

for one-third of that number. Each<br />

month, some 1,400 soldiers are unavailable<br />

to deploy due to medical factors.<br />

According to the report, which uses<br />

2014 data and was released in December,<br />

78,000 soldiers are clinically obese,<br />

and it costs the <strong>Army</strong> more than<br />

$75,000 per new recruit to replace soldiers<br />

discharged due to weight control.<br />

Briefs<br />

Driverless <strong>Army</strong> Trucks Appear<br />

At North American Auto Show<br />

The U.S. <strong>Army</strong> had an attention-getting<br />

display at the 2016 North American<br />

International Auto Show in Detroit: two<br />

example of driverless technology exhibited<br />

by the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Tank Automotive<br />

Research, Development and Engineering<br />

Center.<br />

There was, of course, a Google autonomous<br />

car at the show, but the <strong>Army</strong><br />

showed off its own driverless vehicles.<br />

They are a Peterbilt Class 8 semitractor<br />

commercial vehicle and an M915, a heavy<br />

truck used for long-distance logistics.<br />

The Warren, Mich.-based <strong>Army</strong> automotive<br />

command has been testing driverless<br />

truck technology for several years.<br />

Rather than starting from scratch, the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has joined in research with commercial<br />

truck manufacturers and automakers<br />

that also see a future in driverless vehicles,<br />

if a few hurdles can be overcome. The<br />

<strong>Army</strong> has been making steady progress in<br />

research, with hopes of fielding the first<br />

driverless convoy around 2025.<br />

The U.S. <strong>Army</strong> has had convoys of<br />

self-driving vehicles in testing for years.<br />

Sending driverless vehicles into combat<br />

creates problems that don’t appear on<br />

interstate highways, but the <strong>Army</strong> continues<br />

to explore the possibility of selfdriving<br />

trucks to deliver supplies on humanitarian<br />

missions and resupply some<br />

troops in the field, with the potential of<br />

lower costs and fewer accidents.<br />

Paul D. Rogers, director of the <strong>Army</strong><br />

program, has described driverless vehicles<br />

as a potentially significant safety<br />

measure. That is because many attacks<br />

on soldiers happen along supply routes.<br />

A convoy of driverless vehicles could deliver<br />

the same amount of material as a<br />

convoy with drivers, without concern<br />

about fatigued soldiers or injuries.<br />

First Multicomponent <strong>Army</strong> Unit,<br />

2nd BCT Support Inherent Resolve<br />

The headquarters of 101st Airborne<br />

Division (Air Assault), the first multicomponent<br />

unit in the <strong>Army</strong>, and the<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 11

COMMAND SERGEANTS MAJOR<br />

and<br />

SERGEANTS MAJOR CHANGES*<br />

*Command sergeants major and<br />

sergeants major positions assigned to<br />

general officer commands.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.T. Brady<br />

from U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

WTC to RHC-A (P),<br />

Fort Belvoir, Va.<br />

Sgt. Maj. J. Cecil<br />

from PRMC Ops.,<br />

Honolulu, to MED-<br />

COM G-3/5/7,<br />

Falls Church, Va.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. M.L. Cosper<br />

from USAG Fort<br />

Hood, Texas, to<br />

JTF-Guantanamo<br />

Bay, Cuba.<br />

Command Sgt. Maj.<br />

V.G. Culp from 7th<br />

Transportation Bde.<br />

(Expeditionary), Fort<br />

Eustis, Va., to U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Transportation<br />

Corps and School,<br />

Fort Lee, Va.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. D. Curry from<br />

311th Signal Cmd.<br />

(T), Fort Shafter,<br />

Hawaii, to NETCOM,<br />

Fort Huachuca, Ariz.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. H.E. Dunn<br />

from 20th CBRNE<br />

Cmd., APG, Md., to<br />

Sgt. Maj., FORSCOM<br />

G-3, Fort Bragg, N.C.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. R.C. Luciano<br />

from PRMC, Honolulu,<br />

to DHA, Falls<br />

Church.<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. L. Thomas Jr.<br />

from USAR to Sgt.<br />

Maj., Senior Enlisted<br />

Advisor to<br />

the ASD (M&RA).<br />

Command Sgt.<br />

Maj. J.P. Wills<br />

from 99th Regional<br />

Support Cmd., JB<br />

McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst,<br />

N.J., to USAR.<br />

■ APG—Aberdeen Proving Ground; ASD (M&RA)—Assistant Secretary of Defense for Manpower and Reserve Affairs; Bde.—Brigade; CBRNE—Chemical, Biological,<br />

Radiological, Nuclear and Explosives Cmd.; DHA—Defense Health Agency; FORSCOM—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Forces Cmd.; JB—Joint Base; JTF—Joint Task Force; MEDCOM—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Medical Cmd.; NETCOM—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Network Enterprise Technology Cmd.; PRMC—Pacific Regional Medical Cmd.; RHC-A (P)—Regional Health Cmd.-Atlantic<br />

(Provisional); T—Theater; USAG—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Garrison; USAR—U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Reserve; WTC—Warrior Transition Cmd.<br />

SENIOR EXECUTIVE SERVICE<br />

ANNOUNCEMENTS<br />

G. Garcia, Tier 2,<br />

from Exec. Dir., ITA,<br />

OAASA, to Dir. for<br />

Corp. Info., Office<br />

of the USACE,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

D. Jimenez, Tier 2,<br />

from Exec. Technical<br />

Dir./Dep. to the<br />

Cmdr., HQ, ATEC,<br />

APG, Md., to Asst.<br />

to the DUSA/Dir. of<br />

Test and Eval., Office<br />

of the DUSA,<br />

Washington, D.C.<br />

Tier 1: G. Kitkowski to Regional Business Dir.,<br />

USACE, Pacific Ocean Div., Fort Shafter, Hawaii.<br />

■ APG—Aberdeen Proving Ground; ATEC—<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Test and Evaluation Cmd.; DUSA—<br />

Deputy Undersecretary of the <strong>Army</strong>; ITA—U.S.<br />

<strong>Army</strong> Information Technology Agency;<br />

OAASA—Office of the Administrative Assistant<br />

to the Secretary of the <strong>Army</strong>; USACE—U.S. <strong>Army</strong><br />

Corps of Engineers.<br />

2nd Brigade Combat Team are deploying<br />

this spring to support Operation Inherent<br />

Resolve and will train Iraqi security<br />

forces in the fight against the Islamic<br />

State group. Last June, about 65 members<br />

of the Wisconsin <strong>Army</strong> National<br />

Guard became part of the 101st’s headquarters,<br />

and in January they boarded<br />

buses to Fort Campbell, Ky., to take part<br />

in predeployment training there.<br />

Joining them at Fort Campbell were<br />

53 intelligence soldiers from the Utah<br />

National Guard who are also part of the<br />

new unit and will provide technical support.<br />

Approximately 500 101st soldiers<br />

complete the headquarters, which is part<br />

of the <strong>Army</strong> initiative to integrate reserve<br />

component soldiers with activeduty<br />

soldiers while increasing specific<br />

areas of expertise or filling gaps in specialties<br />

such as intelligence. The 2nd<br />

BCT will deploy with about 1,300 soldiers;<br />

the deployment is a routine rotation<br />

of nine months.<br />

Secretary of Defense Ash Carter spoke<br />

to the soldiers in January at Fort Campbell.<br />

He outlined an accelerated campaign<br />

against the Islamic State that will include<br />

retaking their headquarters city of Mosul.<br />

The task “will not be easy, and it will not<br />

be quick,” Carter said. “The training you<br />

will provide … will be critical.”<br />

AUSA Simplifies Membership<br />

Fees, Offers 2-Year Discount<br />

The Association of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong> has<br />

announced a new, streamlined membership<br />

fee structure, one that allows new<br />

and renewing members to pay $30 for a<br />

two-year membership and $50 for a fiveyear<br />

membership.<br />

The cost of an AUSA Life membership<br />

is $300. A discounted rate of $10 for two<br />

years is available for E-1s to E-4s (private<br />

through corporal/specialist), and for U.S.<br />

Military Academy and ROTC cadets.<br />

AUSA is a 66-year-old educational<br />

nonprofit organization supporting the<br />

<strong>Army</strong>, including soldiers and civilian<br />

workers, all active and reserve component<br />

members, veterans and retirees, family<br />

members and defense industry partners.<br />

“Now more than ever, America’s <strong>Army</strong><br />

needs AUSA, and AUSA needs your<br />

membership support,” said retired Sgt.<br />

Maj. of the <strong>Army</strong> Kenneth O. Preston,<br />

director of AUSA’s Noncommissioned<br />

Officer and Soldier Programs, noting the<br />

turbulent times facing the <strong>Army</strong> and the<br />

many national security risks facing the<br />

United States.<br />

AUSA hosts national and local programs,<br />

including professional development<br />

forums and exhibitions. Membership includes<br />

subscriptions to the nationally<br />

recognized ARMY magazine and AUSA<br />

News, and weekly email updates about<br />

<strong>Army</strong>-related news and events.<br />

—Stories by Toni Eugene<br />

12 ARMY ■ March 2016

Front & Center<br />

The Risk of Another Unsuccessful War<br />

By Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

The Jan. 10 New York Times Magazine<br />

article “The Empty Threat of ‘Boots<br />

on the Ground’” raises again the question<br />

of how to fight modern wars, comparing<br />

two “very long, very costly … not<br />

very successful wars”—Iraq and Afghanistan—with<br />

1995, when President Bill<br />

Clinton “managed to end the fighting<br />

in Bosnia … through air power alone.”<br />

Upon reading that, retired Gen. Gordon<br />

Sullivan, president and CEO of the<br />

Association of the U.S. <strong>Army</strong>, added,<br />

“but only when the NATO allies had<br />

fielded a 57,000 NATO implementation<br />

force ready to invade the area.” The air<br />

campaign set the stage and the cease-fire<br />

precluded an immediate combat assault,<br />

but that NATO force then crossed the<br />

Bosnian border, quelled the conflict and<br />

achieved the objectives initially sought.<br />

Final success depended on occupying the<br />

land and controlling the population.<br />

Nevertheless, “boots on the ground”<br />

ever since have had to deal with the perception<br />

that air power such as bombing<br />

and drone strikes can win modern wars.<br />

Boots on the ground promise a return to<br />

long, drawn-out conflicts, serious casualty<br />

rates for both soldiers and civilians,<br />

and inconclusive declarations of mission<br />

accomplishment. The wars in Korea,<br />

Vietnam and Iraq are examples of such<br />

campaigns.<br />

The argument is not new. It began a<br />

century ago when the fledgling air forces<br />

of the World War I Allies demonstrated<br />

long-range bombers, sank a U.S. warship,<br />

then promised that air power could<br />

win World War II. Even after the end of<br />

hostilities in Europe, air power advocates<br />

believed that a few more months of the<br />

air campaign would have negated the<br />

need for the land forces’ D-Day invasion.<br />

Then the atomic bombs ended hostilities<br />

with Japan, but the war objectives<br />

were achieved only during the five years<br />

of occupation that followed.<br />

The land power argument is anchored<br />

on the realization that wars are won<br />

when soldiers occupy terrain, dominate<br />

populations, and achieve the political objectives<br />

of their parent government.<br />

Cease-fires, truces, armistices and even<br />

surrenders do not end wars; only the creation<br />

of new governments or new lasting<br />

allegiances bring finality to the total<br />

campaign. Conquest is the ultimate solution,<br />

but it’s not always the objective.<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong>/Spc. Steven Hitchcock<br />

Land power advocates point to World<br />

War II, Operation Just Cause in Panama<br />

and Operation Desert Storm as examples<br />

of when properly organized, manned,<br />

equipped and trained forces ended conflicts<br />

and achieved objectives in good<br />

time and with minimum casualties—<br />

though minimum is a relative term.<br />

Compare, for example, the casualty<br />

count from 1939 to May 1944 with<br />

those of the next year, when land power<br />

forces adequate to the task had been<br />

built and committed.<br />

Resolution of the argument is not imminent,<br />

but an understanding of the<br />

costs, time required and objectives associated<br />

with any contemplated military<br />

campaign is vital in today’s world. The<br />

presidential candidates for our upcoming<br />

election are all being asked about their<br />

solutions for the current Middle East situation.<br />

Their answers offer carpet bombing,<br />

no-fly zones, varying ground force<br />

scenarios, or a continuation of current<br />

actions. None seems to give evidence of<br />

understanding the need to identify the<br />

objectives to be sought, the costs, the<br />

forces necessary, and the time to prepare<br />

for a major effort.<br />

Presidents never ask “Are you ready?”<br />

They should understand that the current<br />

<strong>Army</strong> can respond to a crisis overnight,<br />

but that sustaining a major operation requires<br />

an immediate start to build the total<br />

force essential for the campaign. In<br />

World War II, that took two and a half<br />

years. For the Kuwait liberation, it required<br />

six months to organize the allied<br />

force of more than 500,000 that finished<br />

its combat job in 100 hours. For the Iraq<br />

invasion, when then-<strong>Army</strong> Chief of<br />

Staff Gen. Eric Shinseki expressed a<br />

need for 300,000 soldiers to satisfy the<br />

mission requirements, his recommendation<br />

was rebuffed and the Iraq War<br />

never reached a satisfactory conclusion.<br />

The Afghanistan War is being pursued<br />

in like fashion, and its conclusion will<br />

most likely end in like fashion.<br />

This article is not an effort to influence<br />

a political decision to initiate or<br />

participate in a military campaign in the<br />

Middle East. It is not an attempt to reconcile<br />

the differing views concerning air<br />

and land force campaigns. It is, instead, a<br />

hope that those who generate conceptions<br />

for conducting our next military excursion<br />

will fully consider the costs, the<br />

forces, the sustaining means, the time,<br />

the risks to achieving the objectives desired,<br />

and the pre- and post-activities<br />

that will be required to ensure we will<br />

not be adding another “not very successful<br />

war” to our list.<br />

■<br />

Gen. Frederick J. Kroesen, USA Ret., formerly<br />

served as vice chief of staff of the<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> and commander in chief of<br />

U.S. <strong>Army</strong> Europe. He is a senior fellow<br />

of AUSA’s Institute of Land Warfare.<br />

March 2016 ■ ARMY 13

Definition of ‘Decisive’ Depends on Context<br />

By Lt. Gen. James M. Dubik, U.S. <strong>Army</strong> retired<br />

Words matter, for they reflect the<br />

quality of thinking and affect the<br />

judgments we make and the actions we<br />

take. In our everyday speech about the<br />

<strong>Army</strong> and what it does, the term “decisive”<br />

is often used as an absolute. For example,<br />

“The <strong>Army</strong> is the decisive force.”<br />

The problem is, decisive is a relative<br />

term in three important and relevant<br />

senses. First, decisive is relative to context;<br />

second, to combinations; and third,<br />

to proper use.<br />

Every branch of service claims it is decisive.<br />

Most of the time in war, though,<br />

each service contributes importantly to<br />

achieving objectives. “Jointness” is the<br />

idea that in any given tactical or operational<br />

situation, a commander should<br />

select the service capabilities necessary<br />

to achieve the objectives assigned, but<br />

these capabilities are only sufficient<br />

when they are combined and employed<br />

properly.<br />

This reminds us all that each service’s<br />

capabilities and the proper employment<br />

of these capabilities are most often necessary,<br />

but not sufficient. Individually,<br />

each can rarely guarantee the outcome,<br />

but together they can. They are decisive<br />

only in properly used combinations.<br />

When the term decisive is used in an<br />

absolute way, it hides the reality of<br />

fighting.<br />

Everything said of jointness is also<br />

true of combined arms warfare. Many<br />

tactical matters are settled only by a<br />

proper mix of direct and indirect fires,<br />

and of fire and maneuver. Further, producing<br />

a definite result in tactical matters<br />

often rests on the quality and use of<br />

intelligence and effective logistics planning<br />

and execution. Fire, maneuver, intelligence<br />

and logistics are each absolutely<br />

necessary, but they are sufficient<br />

only when properly combined.<br />

At this point, many veterans of Iraq<br />

and Afghanistan would be right to point<br />

out that in multiple cases, fighting was<br />

resolved only when kinetic, combined<br />

arms were mixed with nonkinetic action.<br />

In these cases, even properly mixed<br />

combined arms could not be decisive in<br />

the sense of producing a definite result;<br />

depending on the objective, nonkinetic<br />

actions were also necessary.<br />

Simply put, decisiveness is a function<br />

of at least these elements: the level of<br />

war, the type of war, the aim or objective,<br />

and the period of the war. Perhaps<br />

equally important, producing a decisive<br />

result requires not only the right component<br />

capabilities—military and nonmilitary—but<br />

also their proper use. With respect<br />

to decisiveness, the quality of the<br />

decision and its execution matter as much<br />

as having the right parts.<br />

Level of War<br />

Even though complexity and ambiguity<br />

at the tactical level are often quite<br />

high, tactical examples are relatively easy<br />

to grasp. Actions that have decisive results<br />

at the tactical level do not, however,<br />

merely aggregate to the operational<br />

or strategic levels. The art, science and<br />

logic of good tactics are different from<br />

campaigning at the operational level,<br />

and different still at the strategic level of<br />

war. A good tactician is unlikely to succeed<br />

as an operational artist if he or she<br />

merely expands tactical thinking and<br />

procedures to campaigns.<br />

Military campaigns unfold over time.<br />

The dynamic nature of war assures that<br />

the conditions at the start of a campaign<br />

will not be the same as those at the end.<br />

So proper use of a particular campaign’s<br />

elements requires an adaptive decisionmaking<br />

process. Such a process involves<br />

the ability to sense the gap between the<br />

realities unfolding on the battlefield and<br />

the desired outcomes of the campaign,<br />

and then the issuing of instructions to<br />

adapt actions to reality.<br />

A military campaign is designed to attain<br />

part of a strategic aim, or set the<br />

conditions for the attainment of a strategic<br />

aim. So decisiveness at the operational<br />

level may mean not settling a<br />

matter, but producing a definitive result<br />

that, in turn, sets the conditions for<br />

other acts—whether military or not—to<br />

settle an issue.<br />

Decisiveness at the strategic level is<br />

even more difficult. Strategic leaders use<br />

campaigns, but the art, science and logic<br />

of attaining strategic aims are different<br />

from that of campaigning. Settling a war<br />

involves much more than settling a fight.<br />

The elements necessary to produce a decisive<br />

wartime strategic result include,<br />

but are not limited to, military capabilities.<br />

And the proper use of strategic elements<br />

requires information gathering<br />

and analysis, decisionmaking processes<br />

and adaptive methodologies wider than<br />

just military. Further, because war is essentially<br />

dynamic, using existing bureaucracies—inherently<br />

not good at doing<br />

anything new or fast—often decreases<br />

the quality of strategic-level understanding,<br />

deciding, acting and adapting.<br />

Types of War<br />

Decisive actions, or actions that produce<br />

a definitive result and settle a matter<br />

at each level of war, change with the<br />

type of war that is being waged. In a<br />

conventional war, military force—<br />

whether combined arms or joint—can<br />

often be decisive at the tactical and operational<br />

levels. Such a use of force can<br />

settle much of the matter at hand and<br />

set the conditions for complete settlement<br />

at the strategic level. But not all<br />

wars are conventional.<br />

In many irregular wars, military<br />

force—regardless of how skillfully used—<br />

is merely necessary but not sufficient<br />

even at the tactical and operational levels.<br />

In an irregular war, decisive force<br />

takes on an entirely different hue. The<br />

meaning of “force” itself changes to<br />

“forces”; that is, military force becomes<br />

one of many types of forces necessary to<br />

produce a decisive result—diplomatic,<br />

economic and informational forces, for<br />

example. The term “proper use” also<br />

changes. An irregular war requires that<br />

the varieties of forces involved be sufficiently<br />

integrated from the tactical<br />

through the strategic levels because in<br />

irregular war, the levels of understanding,<br />

deciding, acting and adapting differ<br />

from those of conventional wars.<br />

Aim or Objective<br />

Unconditional surrender, the aim relative<br />

to both Germany and Japan in<br />

World War II, differs from the Korean<br />

War’s aim of re-establishing the 38th<br />

Parallel border between North and<br />

14 ARMY ■ March 2016

South Korea. These two aims differ<br />

from enforcing the Dayton Accords in<br />

Bosnia or sustaining a free, democratic<br />

and non-Communist South Vietnam—<br />

and all differ from the aim of destroying<br />

al-Qaida or the Islamic State group. As<br />

military strategist Carl von Clausewitz<br />

explains in On War, “The smaller the<br />

penalty you demand from your opponent,<br />

the less you can expect him to try<br />

and deny it to you; the smaller the effort<br />

he makes, the less you need to make<br />

yourself. … The political object … will<br />

thus determine both the military objective<br />

to be reached and the amount of effort<br />

it requires.”<br />

Producing decisive results—whether<br />

at the tactical, operational or strategic<br />

level—differs according to the war’s aim,<br />

as do the elements necessary to produce<br />

those results. Different aims also require<br />

adjustments to methodologies and organizations<br />

necessary to understand, decide,<br />

act and adapt.<br />

Period of War<br />

Wars have a beginning, middle and<br />

end, and decisiveness changes at each<br />

point. The Iraq War provides a good example.<br />

The actions necessary to produce<br />

decisive results at the beginning of the<br />

war, which was the period focused on<br />

removing the Saddam Hussein regime,<br />

changed when that task was accomplished.<br />

The Surge of 2007–08 provides<br />

another good example. The mix of<br />

forces—military and nonmilitary—that<br />

were tactically and operationally decisive<br />

could not be decisive strategically. Yet<br />

because many leaders equated war with<br />

fighting, the belief was that the war was<br />

over when the fighting seemed to be<br />

mostly over.<br />

This false belief was fed by at least<br />

three intellectual errors: not recognizing<br />

that tactical and operational decisiveness,<br />

in this case, meant only that<br />

the conditions were set for strategic<br />

decisive action; not recognizing that<br />

tactical and operational decisive action<br />

closed the middle of the war, but not<br />

the end; and not recognizing that to<br />

achieve decisive action strategically and<br />

end the war, both the mix of forces and<br />

how they would be used should have<br />

changed.<br />

Having the right mix of military and<br />

nonmilitary forces is one thing; proper<br />

use—in other words, using them well—<br />

is quite another. Whether at the tactical,<br />

operational or strategic level, using forces<br />

involves at least three dimensions.<br />

The first is an intellectual dimension.<br />

Here, the task is to align the objective<br />

with the ways and means that success at<br />

attaining that objective requires. The<br />

second, an organizational dimension,<br />

recognizes that plans have to be turned<br />

into action and thus, includes the need<br />

for proper organizations and methodologies<br />

for understanding, deciding, acting<br />

and adapting. Execution matters,<br />