e_Paper_Thursday_December 30, 2016

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

22<br />

FRIDAY, DECEMBER <strong>30</strong>, <strong>2016</strong><br />

DT<br />

Opinion<br />

Oppressors and exploiters, be careful<br />

The plight of the Santals is nothing if not heart-wrenching<br />

• Zahir Ahmed and Fiaz Sharif<br />

It’s winter in late November<br />

<strong>2016</strong>. We are accompanied by<br />

a local Santal young man to<br />

visit the Gobindaganj Santal<br />

villages since the massacre in early<br />

November. There is a sense of an<br />

external intervention instantly<br />

from the wire fence around the<br />

crop fields.<br />

Near the temporary<br />

accommodation given to the<br />

evicted villagers, are posters<br />

written in both Bangla and Santal<br />

languages. Whilst not explained,<br />

these posters have statements<br />

which convey the nature of<br />

dissatisfaction -- they are merely<br />

another form of protest.<br />

While the posters are a visual<br />

representation of the Santal, taken<br />

from their muddy house walls<br />

around the villages, the messages<br />

reflect and convey the historical<br />

roots of their struggle, focusing<br />

on some elements of the glorious<br />

historical movements led by<br />

heroes like Kanu and Sidhu whilst<br />

appealing to the government to<br />

give their land back.<br />

They read: “It is our land, we<br />

used to own it” … “Honorable<br />

administration, find our<br />

disappeared individuals” …<br />

“Stop filing cases against the<br />

Santals” … “It is impossible to stop<br />

indigenous peoples’ movement<br />

with a gun.”<br />

Some slogans are written in<br />

in the Santali language: “Diku<br />

pera janum jati Husiar Husiar”<br />

(the oppressors and exploiters,<br />

be careful); “Sidhu kanu rakapen,<br />

hule hul hule hul, bagda farm hasa<br />

lagit, Hule hul hule hul” (wake up<br />

the successors of Sidhu-Kanu,<br />

wake up the inhabitants of Bagda<br />

farm).<br />

Not surprisingly, the legacy of<br />

the Santals’ current protest is more<br />

complex than the official version<br />

would have us believe.<br />

Some Santal farmers showed<br />

their anger with a grimace when<br />

we wanted to talk more. They<br />

said that the whole affair is a bit<br />

disappointing -- they have been<br />

frequently asked similar questions<br />

by numerous journalists and<br />

activities. Nothing was beneficial<br />

to them. They argue: “All are<br />

with the leaders and the sugar<br />

mill authority. Do you have a<br />

solution?”<br />

Some villagers told us that<br />

they had lost household property.<br />

When the district administration<br />

sent food as relief, the protestors<br />

did not receive it although they<br />

had been hungry for three to four<br />

days.<br />

A group of individuals gave an<br />

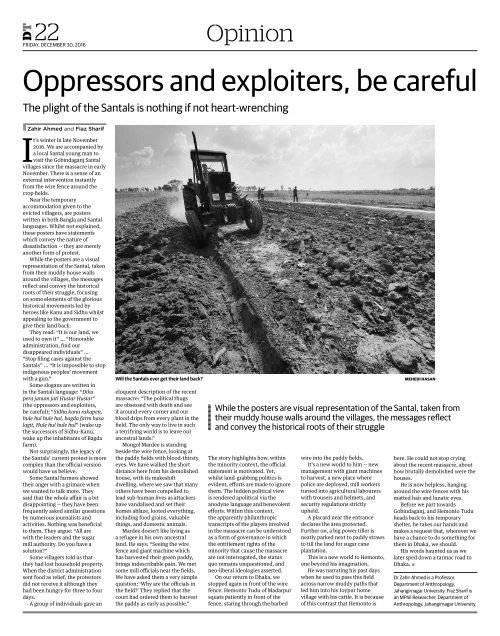

Will the Santals ever get their land back?<br />

eloquent description of the recent<br />

massacre: “The political thugs<br />

are obsessed with death and see<br />

it around every corner and our<br />

blood drips from every plant in the<br />

field. The only way to live in such<br />

a terrifying world is to leave our<br />

ancestral lands.”<br />

Mongol Mardee is standing<br />

beside the wire fence, looking at<br />

the paddy fields with blood-thirsty<br />

eyes. We have walked the short<br />

distance here from his demolished<br />

house, with its makeshift<br />

dwelling, where we saw that many<br />

others have been compelled to<br />

lead sub-human lives as attackers<br />

have vandalised and set their<br />

homes ablaze, looted everything,<br />

including food grains, valuable<br />

things, and domestic animals.<br />

Mardee doesn’t like living as<br />

a refugee in his own ancestral<br />

land. He says: “Seeing the wire<br />

fence and giant machine which<br />

has harvested their green paddy,<br />

brings indescribable pain. We met<br />

some mill officials near the fields.<br />

We have asked them a very simple<br />

question: ‘Why are the officials in<br />

the field?’ They replied that the<br />

court had ordered them to harvest<br />

the paddy as early as possible.”<br />

The story highlights how, within<br />

the minority context, the official<br />

statement is motivated. Yet,<br />

whilst land-grabbing politics is<br />

evident, efforts are made to ignore<br />

them. The hidden political view<br />

is rendered apolitical via the<br />

anodyne language and benevolent<br />

efforts. Within this context,<br />

the apparently philanthropic<br />

transcripts of the players involved<br />

in the massacre can be understood<br />

as a form of governance in which<br />

the entitlement rights of the<br />

minority that cause the massacre<br />

are not interrogated, the status<br />

quo remains unquestioned, and<br />

neo-liberal ideologies asserted.<br />

On our return to Dhaka, we<br />

stopped again in front of the wire<br />

fence. Hemonto Tudu of Madarpur<br />

squats patiently in front of the<br />

fence, staring through the barbed<br />

wire into the paddy fields.<br />

It’s a new world to him -- new<br />

management with giant machines<br />

to harvest, a new place where<br />

police are deployed, mill workers<br />

turned into agricultural labourers<br />

with trousers and helmets, and<br />

security regulations strictly<br />

upheld.<br />

A placard near the entrance<br />

declares the area protected.<br />

Further on, a big power tiller is<br />

neatly parked next to paddy straws<br />

to till the land for sugar cane<br />

plantation.<br />

This is a new world to Hemonto,<br />

one beyond his imagination.<br />

He was narrating his past days<br />

when he used to pass this field<br />

across narrow muddy paths that<br />

led him into his Joypur home<br />

village with his cattle. It is because<br />

of this contrast that Hemonto is<br />

MEHEDI HASAN<br />

While the posters are visual representation of the Santal, taken from<br />

their muddy house walls around the villages, the messages reflect<br />

and convey the historical roots of their struggle<br />

here. He could not stop crying<br />

about the recent massacre, about<br />

how brutally demolished were the<br />

houses.<br />

He is now helpless, hanging<br />

around the wire fences with his<br />

matted hair and lunatic eyes.<br />

Before we part towards<br />

Gobindaganj, and Hemonto Tudu<br />

heads back to his temporary<br />

shelter, he takes our hands and<br />

makes a request that, wherever we<br />

have a chance to do something for<br />

them in Dhaka, we should.<br />

His words haunted us as we<br />

later sped down a tarmac road to<br />

Dhaka. •<br />

Dr Zahir Ahmed is a Professor,<br />

Department of Anthropology,<br />

Jahangirnagar University. Fiaz Sharif is<br />

an MPhil Researcher, Department of<br />

Anthropology, Jahangirnagar University.