CubaTrade-April2017-FLIPBOOK

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

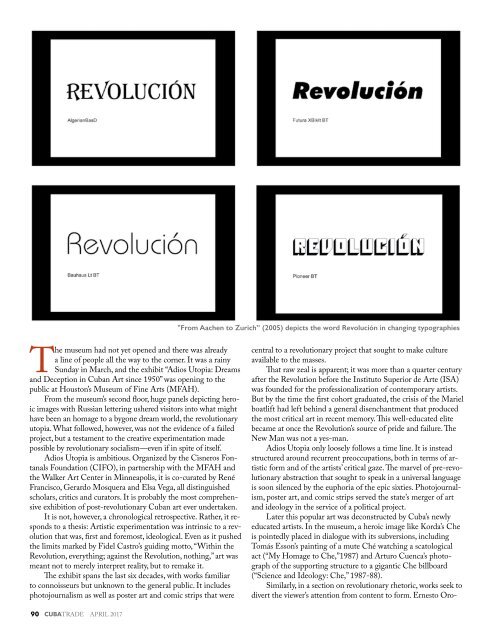

"From Aachen to Zurich” (2005) depicts the word Revolución in changing typographies<br />

“Untitled” (2013) by Alejandro Rodríguez Falcón<br />

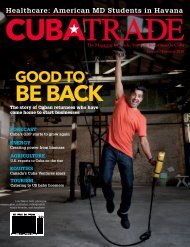

Russian military-style posters at the installation of Adios Utopia<br />

The museum had not yet opened and there was already<br />

a line of people all the way to the corner. It was a rainy<br />

Sunday in March, and the exhibit “Adios Utopia: Dreams<br />

and Deception in Cuban Art since 1950” was opening to the<br />

public at Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFAH).<br />

From the museum’s second floor, huge panels depicting heroic<br />

images with Russian lettering ushered visitors into what might<br />

have been an homage to a bygone dream world, the revolutionary<br />

utopia. What followed, however, was not the evidence of a failed<br />

project, but a testament to the creative experimentation made<br />

possible by revolutionary socialism—even if in spite of itself.<br />

Adios Utopia is ambitious. Organized by the Cisneros Fontanals<br />

Foundation (CIFO), in partnership with the MFAH and<br />

the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, it is co-curated by René<br />

Francisco, Gerardo Mosquera and Elsa Vega, all distinguished<br />

scholars, critics and curators. It is probably the most comprehensive<br />

exhibition of post-revolutionary Cuban art ever undertaken.<br />

It is not, however, a chronological retrospective. Rather, it responds<br />

to a thesis: Artistic experimentation was intrinsic to a revolution<br />

that was, first and foremost, ideological. Even as it pushed<br />

the limits marked by Fidel Castro’s guiding motto, “Within the<br />

Revolution, everything; against the Revolution, nothing,” art was<br />

meant not to merely interpret reality, but to remake it.<br />

The exhibit spans the last six decades, with works familiar<br />

to connoisseurs but unknown to the general public. It includes<br />

photojournalism as well as poster art and comic strips that were<br />

central to a revolutionary project that sought to make culture<br />

available to the masses.<br />

That raw zeal is apparent; it was more than a quarter century<br />

after the Revolution before the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA)<br />

was founded for the professionalization of contemporary artists.<br />

But by the time the first cohort graduated, the crisis of the Mariel<br />

boatlift had left behind a general disenchantment that produced<br />

the most critical art in recent memory. This well-educated elite<br />

became at once the Revolution’s source of pride and failure. The<br />

New Man was not a yes-man.<br />

Adios Utopia only loosely follows a time line. It is instead<br />

structured around recurrent preoccupations, both in terms of artistic<br />

form and of the artists’ critical gaze. The marvel of pre-revolutionary<br />

abstraction that sought to speak in a universal language<br />

is soon silenced by the euphoria of the epic sixties. Photojournalism,<br />

poster art, and comic strips served the state’s merger of art<br />

and ideology in the service of a political project.<br />

Later this popular art was deconstructed by Cuba’s newly<br />

educated artists. In the museum, a heroic image like Korda’s Che<br />

is pointedly placed in dialogue with its subversions, including<br />

Tomás Esson’s painting of a mute Ché watching a scatological<br />

act (“My Homage to Che,”1987) and Arturo Cuenca’s photograph<br />

of the supporting structure to a gigantic Che billboard<br />

(“Science and Ideology: Che,” 1987-88).<br />

Similarly, in a section on revolutionary rhetoric, works seek to<br />

divert the viewer’s attention from content to form. Ernesto Oro-<br />

za’s animation “From Aachen to Zurich” (2005) flashes the term<br />

“Revolution” with changing typographies, as if to strip the term<br />

from its aura, while contributing to its overwhelming presence.<br />

In another section, devoted to what playwright Virginio<br />

Piñera called the “damned circumstance of water everywhere,”<br />

artists ponder the twin conditions of island and exile. The<br />

exhibit’s own farewell is “Inverted Utopias,” comprising works<br />

that challenge that “within” of the Revolution by exposing both<br />

ideology and the critiques that have worked to reinforce it.<br />

Among all these works, one that is small, understated, and<br />

as white as the wall behind it, can be seen as a powerful synthesis<br />

of this proclaimed post-utopian turn in Cuban art. It is a scruffy<br />

square volume of what appears to be paper pulp, still revealing<br />

fragments of words and ink: “Untitled” (2013), by Alejandro<br />

Rodríguez Falcón. Through a manual process of paper recycling,<br />

Rodríguez reduced an official pocket-sized copy of the 1976 Cuban<br />

Constitution—its first socialist Constitution—to wet paper.<br />

In so doing, it turned it into a unique art object.<br />

Like Ai Wei Wei’s famous smashing of archaeological vases,<br />

Rodriguez’s iconoclastic gesture is the art’s genesis. He degrades<br />

the most valuable symbol of the nation, its foundational document,<br />

the revolutionary state’s own contract with its citizens, in<br />

an act of wishful thinking. Then, it carefully displays it behind<br />

glass and inside an oversized frame, as a precious object whose<br />

value no longer resides in its content but in its bare materiality.<br />

Unlike Wei Wei, Rodríguez does not claim the capitalist<br />

market as the arbitrator of value. His might be the kind of act<br />

that in 1990 cost another artist, Angel Delgado, prison time<br />

when he defecated on a Granma newspaper. Today, however,<br />

the Constitution’s defacement hardly produces scandal. Instead,<br />

we squint at the nicely framed volume and celebrate the clever<br />

aesthetics of the transmuted object, whose destruction we were<br />

not invited to witness.<br />

If the museum is the place for salvaged relics, the Cuban<br />

Constitution is there before its time. The Constitution’s power<br />

exceeds its matter; and it still rules the law in the land, unthreatened<br />

by the artist’s act. Which begs the question: Has art, like<br />

the Revolution itself, lost its power to shock and awe, or at least<br />

provoke the imagining of another world?<br />

We know one thing: They no longer need each other, and the<br />

very organization of Adios Utopia proves this point. Cuban state<br />

institutions did not participate, and the artworks were selected<br />

from private collections and museums outside Cuba, apparently<br />

to prevent bureaucratic impediments at an uncertain time in<br />

U.S.-Cuba relations.<br />

One has to wonder if an adios to utopia is not a farewell to<br />

art itself—and hope that this is just a momentary surrender. H<br />

““Adiós Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art Since 1950” is accompanied<br />

by a catalog coordinated by CIFO’s chief curator Eugenio Valdés Figueroa.<br />

The exhibit is on view through May 21 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.<br />

90 CUBATRADE APRIL 2017<br />

APRIL 2017 CUBATRADE<br />

91