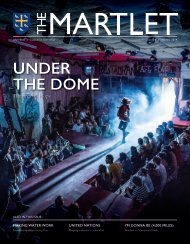

Spring Martlet 2017

Spring Martlet 2017 V2

Spring Martlet 2017 V2

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

DNA Strand<br />

‘When you read your biochemical textbooks,<br />

you’re told this is how transcription works,<br />

this is how translation works and you’re<br />

told the ideal. But, for example, when you<br />

transcribe, how often do you transcribe the<br />

wrong gene? When you translate, how often<br />

do you actually put in the wrong amino acid?<br />

Or do you frame-shift? We’re always taught<br />

the ideal view of how a genome works but<br />

now when you look at the estimates of the<br />

rates at which these errors are occurring<br />

it’s actually stunningly high; it’s actually much<br />

higher than the mutation rate. So in your cells<br />

at the moment you are actually processing<br />

large amounts of mistranslated protein.’<br />

Hurst also shows a pronounced interest<br />

in the significance of his work to the<br />

world outside the lab, both in terms of the<br />

applications of genetic theory to medical<br />

problems but also of the social implications of<br />

working within concepts which have a bearing<br />

on clinical practice. Again, discussions that he<br />

had while in the WCR at Univ played a role in<br />

the formation of these concerns. He cites, for<br />

instance, exchanges with historians as a useful<br />

way to harness the historical significance of<br />

the terms used in his own work. ‘Disease is<br />

a very interesting one historically,’ he reflects,<br />

‘In the 19th Century what was a mental<br />

disease and what was criminality was very<br />

poorly differentiated…today we do attempt<br />

to differentiate, but I doubt very much if that’s<br />

perfect.’ He acknowledges that the historical<br />

baggage behind the term disease determines<br />

that it has to be deployed judiciously and<br />

sensitively; ‘I’m colour-blind and I never know<br />

whether to call that a disease: I can trace it<br />

back, I know I’ve got a particular mutation in<br />

the receptors, and that’s fine as a mechanistic<br />

description of what’s going on in my head, but<br />

whether or not I’d want to call it a disease<br />

attaches a large amount of baggage with it.’<br />

Quite consciously, he has turned the findings<br />

of his research towards practical applications<br />

in diagnostics. ‘I am engaged in a project<br />

examining the world’s most interesting<br />

disease,’ he explains with some excitement.<br />

That disease in his view is pre-eclampsia; a<br />

condition generally affecting first pregnancy,<br />

which, if allowed to run to course, kills both<br />

mother and baby. Hurst explains that because<br />

of the high mortality rate for mother and<br />

baby where the condition is present, ‘This<br />

must have been one of the most powerful<br />

selective forces in human evolution.’ His<br />

hypothesis frames pre-eclampsia as a<br />

misplaced immunological response to the<br />

foetus; it is probably the mother’s body misrecognising<br />

the foetus and the immune system<br />

responding as it does as a defence against<br />

other foreign material. ‘There is no universally<br />

accepted model for pre-eclampsia’, Hurst<br />

explains, reflecting on the current difficulty<br />

in handling the disease – the only cure at<br />

present is a caesarian section. The natural<br />

implication is that work like Hurst’s which<br />

helps to understand the condition’s nature<br />

and causes could prove momentous in finding<br />

ways to treat and prevent it.<br />

Vital to his work on this project has been cooperation<br />

with a team of researchers in Berlin.<br />

Speaking more broadly, he reflects that such<br />

collaborations and productive conversations<br />

with closer colleagues have been instrumental<br />

to the development and completion of<br />

much of his work and emphasises that in<br />

his view supportive and friendly working<br />

relationships are the most productive: ‘I like<br />

collaborating with nice people: a really great<br />

problem is something really important’ he<br />

says, ‘But actually a lot of science is done by<br />

simply talking to people who you can really<br />

get on with.’ Evident in the way that Hurst<br />

talks about his discursive working method is<br />

that sense of intellectual and interdisciplinary<br />

exchange which first sparked his enthusiasm<br />

in Univ’s WCR. ‘On top of that, of course,’<br />

he continues, reflecting particularly on the<br />

WCR, with a distinct tone of fondness,<br />

‘They were all stupendously smart people.<br />

In retrospect, I think there’s nothing more<br />

glorious than spending time with stupendously<br />

smart people who think differently from you,<br />

or even if they don’t think differently have<br />

thought about different things.’ It is evident<br />

from the way that he talks about his work that<br />

his enduring value of a thoughtful, challenging<br />

and multi-sided approach is key to the success<br />

of his research.<br />

24 THE MARTLET | SPRING <strong>2017</strong>