Spring Martlet 2017

Spring Martlet 2017 V2

Spring Martlet 2017 V2

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

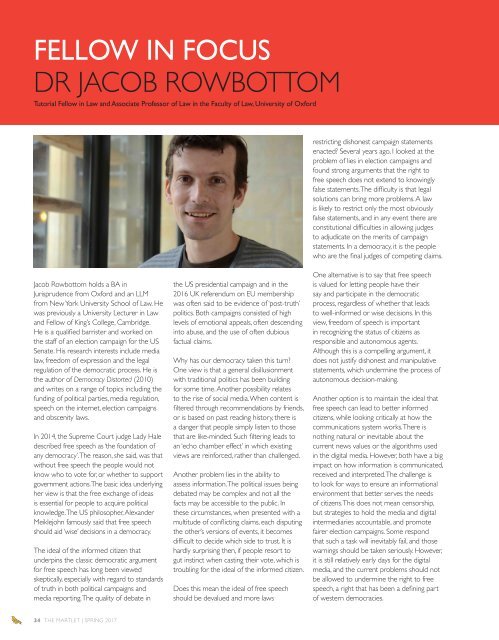

FELLOW IN FOCUS<br />

DR JACOB ROWBOTTOM<br />

Tutorial Fellow in Law and Associate Professor of Law in the Faculty of Law, University of Oxford<br />

restricting dishonest campaign statements<br />

enacted? Several years ago, I looked at the<br />

problem of lies in election campaigns and<br />

found strong arguments that the right to<br />

free speech does not extend to knowingly<br />

false statements. The difficulty is that legal<br />

solutions can bring more problems. A law<br />

is likely to restrict only the most obviously<br />

false statements, and in any event there are<br />

constitutional difficulties in allowing judges<br />

to adjudicate on the merits of campaign<br />

statements. In a democracy, it is the people<br />

who are the final judges of competing claims.<br />

Jacob Rowbottom holds a BA in<br />

Jurisprudence from Oxford and an LLM<br />

from New York University School of Law. He<br />

was previously a University Lecturer in Law<br />

and Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge.<br />

He is a qualified barrister and worked on<br />

the staff of an election campaign for the US<br />

Senate. His research interests include media<br />

law, freedom of expression and the legal<br />

regulation of the democratic process. He is<br />

the author of Democracy Distorted (2010)<br />

and writes on a range of topics including the<br />

funding of political parties, media regulation,<br />

speech on the internet, election campaigns<br />

and obscenity laws.<br />

In 2014, the Supreme Court judge Lady Hale<br />

described free speech as ‘the foundation of<br />

any democracy’. The reason, she said, was that<br />

without free speech the people would not<br />

know who to vote for, or whether to support<br />

government actions. The basic idea underlying<br />

her view is that the free exchange of ideas<br />

is essential for people to acquire political<br />

knowledge. The US philosopher, Alexander<br />

Meiklejohn famously said that free speech<br />

should aid ‘wise’ decisions in a democracy.<br />

The ideal of the informed citizen that<br />

underpins the classic democratic argument<br />

for free speech has long been viewed<br />

skeptically, especially with regard to standards<br />

of truth in both political campaigns and<br />

media reporting. The quality of debate in<br />

the US presidential campaign and in the<br />

2016 UK referendum on EU membership<br />

was often said to be evidence of ‘post-truth’<br />

politics. Both campaigns consisted of high<br />

levels of emotional appeals, often descending<br />

into abuse, and the use of often dubious<br />

factual claims.<br />

Why has our democracy taken this turn?<br />

One view is that a general disillusionment<br />

with traditional politics has been building<br />

for some time. Another possibility relates<br />

to the rise of social media. When content is<br />

filtered through recommendations by friends,<br />

or is based on past reading history, there is<br />

a danger that people simply listen to those<br />

that are like-minded. Such filtering leads to<br />

an ‘echo chamber effect’ in which existing<br />

views are reinforced, rather than challenged.<br />

Another problem lies in the ability to<br />

assess information. The political issues being<br />

debated may be complex and not all the<br />

facts may be accessible to the public. In<br />

these circumstances, when presented with a<br />

multitude of conflicting claims, each disputing<br />

the other’s versions of events, it becomes<br />

difficult to decide which side to trust. It is<br />

hardly surprising then, if people resort to<br />

gut instinct when casting their vote, which is<br />

troubling for the ideal of the informed citizen.<br />

Does this mean the ideal of free speech<br />

should be devalued and more laws<br />

One alternative is to say that free speech<br />

is valued for letting people have their<br />

say and participate in the democratic<br />

process, regardless of whether that leads<br />

to well-informed or wise decisions. In this<br />

view, freedom of speech is important<br />

in recognizing the status of citizens as<br />

responsible and autonomous agents.<br />

Although this is a compelling argument, it<br />

does not justify dishonest and manipulative<br />

statements, which undermine the process of<br />

autonomous decision-making.<br />

Another option is to maintain the ideal that<br />

free speech can lead to better informed<br />

citizens, while looking critically at how the<br />

communications system works. There is<br />

nothing natural or inevitable about the<br />

current news values or the algorithms used<br />

in the digital media. However, both have a big<br />

impact on how information is communicated,<br />

received and interpreted. The challenge is<br />

to look for ways to ensure an informational<br />

environment that better serves the needs<br />

of citizens. This does not mean censorship,<br />

but strategies to hold the media and digital<br />

intermediaries accountable, and promote<br />

fairer election campaigns. Some respond<br />

that such a task will inevitably fail, and those<br />

warnings should be taken seriously. However,<br />

it is still relatively early days for the digital<br />

media, and the current problems should not<br />

be allowed to undermine the right to free<br />

speech, a right that has been a defining part<br />

of western democracies.<br />

34 THE MARTLET | SPRING <strong>2017</strong>