COMPENDIO_DE_GEOLOGIA_Bolivia

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PRESI<strong>DE</strong>NTE<br />

VICEPRESI<strong>DE</strong>NTE <strong>DE</strong> NEGOCIACIONES<br />

INTERNACIONALES Y CONTRATOS<br />

VICEPRESI<strong>DE</strong>NTE <strong>DE</strong> OPERACIONES<br />

EDITOR<br />

E-mail:<br />

DIRECCION POSTAL<br />

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB<br />

TRADUCCION AL INGLES<br />

Portada:

VOLUMEN 18 NUMERO 1-2 JUNIO 2000<br />

COCHABAMBA - BOLIVIA

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

A- Compendio de Geología de <strong>Bolivia</strong> / <strong>Bolivia</strong>n Geology Compendium<br />

por / by Ramiro Suárez-Soruco<br />

1 Introducción / Introduction 1<br />

2 Altiplano / Altiplano 13<br />

3 Cordillera Oriental / Eastern Cordillera 39<br />

4 Sierras Subandinas / Subandean Ranges 77<br />

5 Llanura Beniana, Cuenca del Madre de Dios y Plataforma Beniana 101<br />

Beni Plain, Madre de Dios Basin and Beni Platform<br />

6 Llanura Chapare-Boomerang y Sierras y Llanura Chiquitana 111<br />

Chapare-Boomerang Plain and Chiquitos Range and Plain<br />

7 Cratón de Guaporé / Guaporé Craton 127<br />

B - Contribuciones especiales / Special contributions<br />

8 Potencial de hidrocarburos / Hydrocarbon potential 145<br />

Carlos Oviedo-Gómez & Ricardo Morales-Lavadenz<br />

9 Las provincias y épocas metalogenéticas de <strong>Bolivia</strong> en su marco geodinamico 167<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>n provinces and metalogenetic epochs in its geodynamic context<br />

Bertrand Heuschmidt & Vitaliano Miranda-Angles<br />

10 Tectónica de placas y evolución estructural en el margen continental activo<br />

de Sudamérica 199<br />

Plate tectonics and structural evolution at the South American active<br />

continental margin.<br />

Reinhard Roßling

por / by<br />

RAMIRO SUAREZ-SORUCO<br />

ramsu@bo.net

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

Capítulo 1<br />

INTRODUCCION<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

Generalidades<br />

El estudio de la Geología de <strong>Bolivia</strong> se inició el siglo pasado, y<br />

continuó en el presente, con geólogos europeos de renombre como<br />

Alcides d’Orbigny, Gustavo Steinmann, Román Kozlowski, y otros<br />

muchos. A partir de los años treinta se incorporaron a la tarea de<br />

interpretar y describir la geología del país los primeros geólogos<br />

bolivianos, Jorge Muñoz Reyes, Raúl Canedo Reyes, Celso Reyes<br />

y otros, que junto con investigadores de otros paises, como<br />

Federico Ahlfeld y Leonardo Branisa, contribuyeron a la enseñanza<br />

de las ciencias geológicas, y a la exploración en busca no solo del<br />

conocimiento científico, sino también de recursos minerales y<br />

energéticos. La creación de instituciones como Yacimientos<br />

Petrolíferos Fiscales <strong>Bolivia</strong>nos, Corporación Minera de <strong>Bolivia</strong> y<br />

la Departamento Nacional de Geología, así como la carrera de<br />

Geología en las universidades de San Andrés (La Paz), Tomás<br />

Frías (Potosí) y Técnica de Oruro, permitió formar en el país los<br />

profesionales que actualmente contribuyen a ampliar el<br />

conocimiento de la Geología de <strong>Bolivia</strong>.<br />

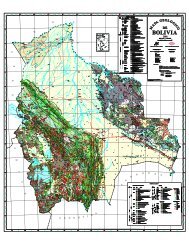

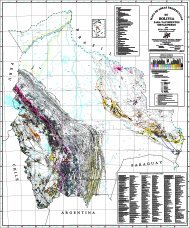

La elaboración de hojas geológicas (1:100.000 y 1:250.000) de la<br />

Carta Geológica de <strong>Bolivia</strong> fue realizada por el Servicio Geológico<br />

de <strong>Bolivia</strong> durante los últimos 30 años. GEOBOL, desde 1996,<br />

junto con otras instituciones, conforma el Servicio Nacional de<br />

Geología y Minería (SERGEOMIN). Esta institución, con el<br />

aporte de información geológica de YPFB y la colaboración<br />

financiera del Banco Mundial, ha elaborado, luego de casi veinte<br />

años, un nuevo Mapa Geológico de <strong>Bolivia</strong> a escala 1: 1.000.000,<br />

que constituye una versión actualizada del publicado en 1968, y al<br />

que se transfirió el resultado de la investigación y los<br />

conocimientos logrados hasta la fecha por profesionales de las<br />

instituciones involucradas y de otras entidades afines.<br />

General Aspects<br />

The study of the Geology of <strong>Bolivia</strong> started during the previous<br />

century, and continued into the present with well-known European<br />

geologists such as Alcides d’Orbigny, Gustavo Steinmann, Román<br />

Kozlowski, and many other. Starting in the 30’s, the first <strong>Bolivia</strong>n<br />

geologists, Jorge Muñoz Reyes, Raúl Canedo Reyes, Celso Reyes,<br />

and others, joined into the task of interpreting and describing the<br />

geology of the country. Together with researchers from other<br />

countries, such as Federico Ahlfeld and Leonardo Branisa, they<br />

contributed to the teaching of geological sciences and to<br />

exploration, not only in search for scientific knowledge, but also<br />

for mineral and energy resources. The creation of institutions such<br />

as Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales <strong>Bolivia</strong>nos (YPFB), the<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>n Mining Corporation and the National Geology<br />

Department, as well as the Geology Departments at the<br />

Universities of San Andrés (La Paz), Tomás Frías (Potosí) and<br />

Technical University of Oruro, made possible to train, in the<br />

country, professionals who currently contribute to expanding the<br />

knowledge on the Geology of <strong>Bolivia</strong>.<br />

During the last 30 years, the Geological Survey of <strong>Bolivia</strong><br />

(GEOBOL) elaborated the geological sheets (1:100,000 and<br />

1:250,000) of the Geological Chart of <strong>Bolivia</strong>. Since 1996,<br />

GEOBOL, together with other institutions, make up the National<br />

Geology and Mining Survey (SERGEOMIN). With YPFB´s<br />

geological contributions and the financial aid of the World Bank,<br />

after nearly twenty years, this institution has prepared a new<br />

Geological Map of <strong>Bolivia</strong>, in a 1:1,000,000 scale. This map is an<br />

updated version of the map published in 1968, to which the<br />

research results and the knowledge obtained up to the date by<br />

professionals of the involved institutions and other similar entities<br />

were transferred.

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

En ese sentido, esta síntesis describe en cada uno de los siguientes<br />

capítulos, el conocimiento actual de cada una de estas áreas, de<br />

acuerdo a una relación geocronológica desde los tiempos<br />

proterozoicos al reciente. Sin embargo, se debe advertir al lector<br />

que el desarrollo de un tema de esa magnitud fácilmente ocuparía<br />

varios tomos, y en este compendio se presentará sólo una síntesis,<br />

que podrá ser ampliada con la lectura de los trabajos figurados en<br />

las referencias bibliográficas insertadas al final de cada capítulo.<br />

In this sense, in each of the following chapters, this synthesis<br />

describes the current knowledge on each of these fields, according<br />

to a geochronological relation from the Proterozoic times until the<br />

present. However, the reader must be warned that the development<br />

of such a topic would easily take up several volumes, and this<br />

compendium will only present a synthesis which can be<br />

complemented by reading the works listed in the bibliographical<br />

references included at the end of each chapter.<br />

Ciclos tectosedimentarios y orogénicos<br />

Con la finalidad de interpretar y ordenar las secuencias a través del<br />

tiempo geológico, se han propuesto y definido grandes ciclos<br />

tectosedimentarios y orogénicos para el país y regiones vecinas.<br />

Cuatro de ellos han sido establecidos para el Proterozoico, y otros<br />

cuatro para la secuencia fanerozoica.<br />

Los ciclos proterozoicos: Transamazónico y Brasiliano fueron<br />

definidos por Almeida et al. (1976), y los ciclos San Ignacio y<br />

Sunsás por Litherland & Bloomfield (1981).<br />

Tectonic Sedimentary and Orogenic Cycles<br />

With the purpose of interpreting and arranging the sequences<br />

through geological time, great tectonic sedimentary and orogenic<br />

cycles have been proposed and defined for the country and the<br />

neighboring regions. Four of these have been determined for the<br />

Proterozoic and other four for the Phanerozoic sequence.<br />

The Proterozoic cycles, namely the Transamazonic and the<br />

Brazilian, were established by Almeida et al. (1976), and the San<br />

Ignacio and Sunsás cycles by Litherland & Bloomfield (1981).<br />

EON CICLO EDA<strong>DE</strong>S<br />

ANDINO<br />

Reciente<br />

Jurásico inferior<br />

SUBANDINO<br />

Triásico superior<br />

Carbonífero superior<br />

FANEROZOICO<br />

Carbonífero inferior<br />

CORDILLERANO<br />

Silúrico inferior<br />

TACSARIANO<br />

Ordovícico superior<br />

Cámbrico superior<br />

BRASILIANO<br />

900 – 540 Ma<br />

PROTEROZOICO<br />

SUNSAS<br />

SAN IGNACIO<br />

TRANSAMAZONICO<br />

1280 – 900 Ma<br />

1600 – 1280 Ma<br />

> 1600 Ma<br />

Fig. 1.1 Ciclos Tectosedimentarios de <strong>Bolivia</strong><br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>n Tectonic-Sedimentary Cycles<br />

Los ciclos fanerozoicos: Tacsariano, Cordillerano y Subandino<br />

fueron establecidos por Suárez-Soruco (1982, 1983), y el Ciclo<br />

Andino por Steinmann (1929). Posteriormente, ha sido propuesta<br />

por Oller (1992) la subdivisión del Ciclo Andino con los numerales<br />

I y II, división que será utilizada en este trabajo.<br />

The Phanerozoic cycles, Tacsarian, Cordilleran and Subandean,<br />

were established by Suárez-Soruco (1982, 1983), and the Andean<br />

Cycle by Steinmann (1929). Later on, the subdivision of the<br />

Andean Cycle into numbers I and II, which will be used in this<br />

paper, was proposed by Oller (1992).<br />

2

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

La historia geológica del Gondwana Occidental, y del sector<br />

boliviano en particular, puede ser dividida en dos grandes<br />

episodios: Pre-Andino y Andino. La separación entre ambos está<br />

dada por la disgregación del Gondwana (ca 200 Ma).<br />

El episodio Pre-Andino comprende como primera etapa a los ciclos<br />

proterozoicos, hasta la etapa de apertura del Oceáno Iapetus y el<br />

cierre de los oceános Adamastor y Mozambique, en el modelo de<br />

Grunow, 1996, y la consiguiente formación de la Triple Fractura<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>na que da origen al Rift Contaya-Tacsara a fines del Ciclo<br />

Brasiliano. La segunda etapa pre-andina se inicia en el Tacsariano,<br />

es decir desde la apertura del rift hasta la separación del Gondwana.<br />

El Episodio Andino se inicia hacia los 200 Ma, en el Jurásico<br />

temprano, y se extiende hasta el presente.<br />

The geological history of the Western Gondwana, and particulary<br />

of the <strong>Bolivia</strong>n sector, can be divided into two large episodes: the<br />

Pre-Andean and the Andean. The separation between the two was<br />

determined by the breakup of Gondwana (ca. 200 Ma).<br />

In its first stage, the Pre-Andean episode comprises the Proterozoic<br />

cycles, up to the opening stage of the Iapetus Ocean and the closing<br />

of the Adamastor and Mozambique Oceans, in Grunow’s model,<br />

1996, and the ensuing formation of the <strong>Bolivia</strong>n Triple Fracture,<br />

which originates the Contaya-Tacsara Rift at the end of the<br />

Brazilian Cycle. The second Pre-Andean stage starts during the<br />

Tacsarian; that is, from the rift opening to the separation of the<br />

Gondwana. The Andean Episode starts towards 200 Ma, during<br />

the Lower Jurassic, and extends up to the present.<br />

Fig. 1.2 Cuadro Estratigráfico del Altiplano, Cordillera Oriental y Subandino<br />

Stratigraphic framework of Altiplano, Eastern Cordillera and Subandean<br />

3

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

M D<br />

S<br />

A<br />

C O<br />

B<br />

P M C h<br />

C<br />

G u<br />

Fig. 1.3 Triple Fractura <strong>Bolivia</strong>na (tri-radio rojo) y<br />

Lineamiento del Sistema de Fallas Cordillera Real-<br />

Aiquile-Tupiza (línea roja) que divide el Macizo de<br />

Arequipa-Huarina, del Cratón de Guaporé. (Modificado<br />

en el Mapa Tectono-Estratigráfico de <strong>Bolivia</strong> de Sempere<br />

et al., 1988).<br />

A<br />

A<br />

A<br />

O r<br />

F H<br />

C O<br />

C O<br />

I<br />

A<br />

S<br />

A<br />

S<br />

A<br />

C h a<br />

TRIPLE FRACTURA BOLIVIANA<br />

(PROTEROZOICO)<br />

SISTEMA <strong>DE</strong> FALLAS (ACTUAL)<br />

CORDILLERA REAL - AIQUILE - TUPI-<br />

ZA<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>n triple joint (red tri-radio) and Cordillera Real<br />

Fault System (red line) that divides de Arequipa-Huarina<br />

Massif and Guapporé Craton. Modified in Tecto-<br />

Stratigraphic Map of Sempere et al., 1988).<br />

FK: Falla Khenayani; CALP: Cabalgamiento Altiplánico Principal;<br />

FCC: Frente de Cabalgamiento Coniri; FSV: Falla San Vicente;<br />

FAT: Falla Aiquile-Tupiza; CCR: Cabalgamiento Cordillera Real;<br />

FT: Falla Tapacarí; CANP: Cabalgamiento Andino Principal; CFP:<br />

Cabalgamiento Frontal Principal; FCSA: Frente de Cabalgamiento<br />

Subandino; AOc: Altiplano Occidental; AOr: Altiplano Oriental;<br />

FH: Faja Plegada de Huarina; COr: Cordillera Oriental; IA:<br />

Interandino; SA: Subandino; CGu: Cratón de Guaporé; PMo-Chi:<br />

Plataforma Mojeño Chiquitana.<br />

Episodio Pre-Andino<br />

Pre-Andean Episode<br />

Durante el Arqueozoico y Proterozoico, el primitivo Escudo<br />

Brasilero experimentó una serie de modificaciones consistentes en<br />

la acreción de nuevos terrenos (Terrenos Chuiquitanos), formación<br />

de cuencas intracratónicas, y el desarrollo de importantes orógenos<br />

como los de San Ignacio, Sunsás, Aguapei (Litherland et al., 1986;<br />

Meneley, 1991).<br />

Los principales terrenos acrecionados durante el Arqueozoico y<br />

Proterozoico al Escudo Brasileño Central (1600-2600 Ma.),<br />

corresponden a terrenos de aproximadamente 1000-1600 Ma. como<br />

Rondonia-Sunsás y Chaco-Paraná seguidos por otros terrenos<br />

más jóvenes, entre 570 y 1000 Ma, como los de Cerro León y<br />

Chiquitos (Meneley, 1991).<br />

During the Archeozoic and Proterozoic, the primitive Brazilian<br />

Shield underwent a series of modifications, which consisted of the<br />

accretion of new land (Chiquitan Terranes), the formation of<br />

intracratonal basins, and the development of important orogens,<br />

such as those of San Ignacio, Sunsás, Aguapei (Litherland et al.,<br />

1986; Meneley, 1991).<br />

During the Archeozoic and Proterozoic, the main accretion of<br />

terranes to the Central Brazilian Shield (1600-2600 Ma) refers to<br />

terranes of approximately 1000-1600 Ma., such as Rondonia-<br />

Sunsás and Chaco-Paraná, followed by other younger terrane,<br />

between 570 and 1000 Ma, such as that of Cerro León and<br />

Chiquitos (Meneley, 1991).<br />

Uno de los principales aspectos a definir en el futuro es el orígen de<br />

la microplaca o Macizo de Arequipa. A la fecha se han propuesto<br />

dos hipótesis: la primera que considera que se trata de un terreno<br />

alóctono, posiblemente originado en el borde del Continente de<br />

Laurentia durante la orogenia grenvilliana (Gorhrbandt, 1992;<br />

Wasteneys et al., 1995), y la segunda, aceptada en el presente<br />

trabajo, así como por Avila-Salinas (1996) y Erdtmann & Suárez-<br />

Soruco (1999), que considera que corresponde a un terreno<br />

autóctono, dislocado del Escudo Brasilero a fines del Proterozoico<br />

a partir de la “Triple Fractura <strong>Bolivia</strong>na” (Suárez-Soruco, 1989).<br />

One of the main aspects to be defined in the future is the origin of<br />

the microplate or Arequipa Massif. Until now, two hypotheses<br />

have been proposed: the first considers it to be allochthonous<br />

terrane, which possible originated on the edge of the Laurentia<br />

Continent during the Grevillian Orogeny (Gorhrbandt, 1992;<br />

Wasteneys et al., 1995); and the second, accepted in the present<br />

paper, as well as by Avila-Salinas (1996) and Erdtmann & Suárez-<br />

Soruco (1999) considers it to be autochthonous land that wrenched<br />

from the Brazilian Shield at the end of the Proterozoic from<br />

“<strong>Bolivia</strong>n Triple Fracture” (Suárez-Soruco, 1989).<br />

4

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

A partir del Ciclo Tacsariano, y durante la mayor parte del<br />

Paleozoico inferior, el desarrollo extensional de los brazos N-S y<br />

NW-SE, así como la consiguiente separación de la “sub-placa<br />

móvil” de Arequipa formó en territorio boliviano las cuencas<br />

intracratónicas de los ciclos Brasiliano, Tacsariano y Cordillerano<br />

(Rift Contaya-Tacsara).<br />

Aceptando que la Placa de Arequipa corresponde a un disloque del<br />

Cratón Amazónico, en este trabajo proponemos cambiar el nombre<br />

de Placa o Terreno de Arequipa-Belén-Antofalla, establecido en<br />

sentido N-S tomando el nombre de esas localidades proterozoicas,<br />

por el de Macizo de Arequipa-Huarina (Fig. 1.3), haciendo<br />

referencia a su extensión oriental en territorio boliviano, por cuanto<br />

este macizo incluiría la Faja Plegada de Huarina. En este sentido, el<br />

Macizo de Arequipa-Huarina estaría separado del actual Cratón de<br />

Guaporé por el sistema de fallas Cordillera Real – Aiquile - Tupiza<br />

de Sempere et al., (1988)<br />

Durante el Ciclo Brasiliano, la fractura permitió la extrusión de<br />

rocas básicas y ultrabásicas en el centro y sur de la cuenca<br />

boliviana. Al inicio del Ciclo Tacsariano, la cuenca fue<br />

inicialmente pequeña, de mayor desarrollo y profundidad en el<br />

sector sur. Durante el Cámbrico superior se rellena con sedimentos<br />

clásticos marinos, gruesos y no fosilíferos. El tamaño del grano fue<br />

decreciendo paulatinamente en el Ordovícico inferior (facies flysh<br />

con graptolites). En esa época se desarrolla una importante<br />

comunidad marina de invertebrados, con especies comunes a las de<br />

la costa este de Laurentia (Newfounland-Oaxaca). A partir del<br />

Arenigiano se reinicia la actividad volcánica submarina en el sur,<br />

con la inyección e interestratificación de tobas cineríticas y flujos<br />

dacíticos, que continuó en el Llanvirniano con sills doleríticos y<br />

flujos de basaltos submarinos relacionados e interestratificados con<br />

la Formación Capinota, y finalmente en el Caradociano, lavas<br />

almohadilla de andesitas basálticas y traquiandesitas espilitizadas<br />

relacionadas con la Formación Amutara, actividad que implica un<br />

rifting de la corteza continental (Avila-Salinas, 1996).<br />

Hacia fines del Ordovícico medio, la Placa de Arequipa-Huarina<br />

empezó un desplazamiento sinistral que ensanchó la cuenca en el<br />

sector central y norte, produciendo el depósito de importantes<br />

secuencias marinas llanvirniano-ashgillianas. El extremo meridional<br />

de la placa, debido a esta rotación sinistral, colisionó con el<br />

Macizo Chaco-Pampeano, produciendo la intrusión de granitoides,<br />

y la formación de cuencas de trasarco en el noroeste argentino<br />

(Fase Oclóyica).<br />

Durante el Ciclo Cordillerano, la cuenca posiblemente corresponde<br />

a un rift de trasarco. En el Silúrico inferior hay mayor subsidencia,<br />

especialmente en el sector suroccidental, a causa del levantamiento<br />

producido por la intrusión de granitoides en territorio argentino. En<br />

esta época el borde de cuenca se extendió y amplió considerablemente.<br />

Desde el Silúrico superior se hace más evidente la<br />

influencia costera, aparecen las primeras plantas vasculares, y al<br />

final del ciclo, sobre estuarios o lagunas costeras se desarrollan<br />

primitivos bosques de helechos y licofitas.<br />

A fines del Ciclo Cordillerano se produjo la primera deformación<br />

tectónica importante, que involucra a las secuencias tacsarianas y<br />

cordilleranas, la Fase Chiriguana (sensu YPFB) o Eohercínica, y<br />

que conduce a la formación de un orógeno. Estos movimientos, y<br />

Starting with the Tacsarian Cycle and during the greater part of the<br />

Lower Paleozoic, the extensional development of the N-S and NW-<br />

SE branches, and the subsequent separation of the “mobile subplate”<br />

of Arequipa, formed the intracratonal basins of the<br />

Brazilian, Tacsarian and Cordillerano cycles (Contaya-Tacsara<br />

Rift) in <strong>Bolivia</strong>n territory.<br />

Accepting that the Arequipa Plate relates to a wrench of the<br />

Amazonic Craton, in this paper we set out to change the name of<br />

the Plate or Terrane of Arequipa-Belén-Antofalla, established in a<br />

N-S trend taking the name of those Proterozoic localities, to the<br />

Arequipa-Huarina Massif (fig. 1.3), making reference to its<br />

eastern extension in <strong>Bolivia</strong>n territory, since this Massif would<br />

include the Huarina Fold Belt. In this sense, the Arequipa-Huarina<br />

Massif would be separated from the actual Guaporé Craton by the<br />

Cordillera Real-Aiquile-Tupiza faults of Sempere et al., (1988).<br />

During the Brazilian Cycle, the fracture allowed the extrusion of<br />

basic and ultrabasic rocks from the center and south of the <strong>Bolivia</strong>n<br />

basin. At the beginning of the Tacsarian Cycle, the basin was<br />

initially small, with greater development and depth in the southern<br />

sector. During the Upper Cambrian, this basin was filled with<br />

coarse, non-fossil, marine, clastic sediments. During the Lower<br />

Ordovician, the size of the grain decreased gradually (flysh facies<br />

with graptolites). During this time, a significant sea invertebrate<br />

community developed, similar to that of the eastern coast of<br />

Laurentia (Newfoundland-Oaxaca). Starting with the Arenigian,<br />

submarine volcanic activity starts again in the south, with the<br />

injection and interbedding of cineritic tuffs and dacitic flows,<br />

continuing during the Llanvirnian with doleritic sills and submarine<br />

basalt flows that are related to and interbedded with the Capinota<br />

Formation, and finally, during the Caradocian, with basaltic<br />

andesite pillow lava and spilitized trachyandesites related to the<br />

Amutura Formation. This activity involves a rifting of the<br />

continental crust (Avila-Salinas, 1996).<br />

Towards the end of the Middle Ordovician, the Arequipa-Huarina<br />

Plate started a sinistral displacement that widened the basin on the<br />

central and Northern sectors, producing the deposit of important<br />

llanvirnian-ashgillian marine sequences. Due to this sinistral<br />

rotation, the plate’s meridional end collided with the Chaco-<br />

Pampeano Massif, causing the intrusion of granitoids and the<br />

formation of backarc basins in northwestern Argentina (Ocloyic<br />

Phase).<br />

During the Cordilleran Cycle, the basin is likely to correspond to a<br />

backarc rift. During the Lower Silurian, there is greater subsidence,<br />

especially in the southwestern sector, due to the elevation<br />

produced by the intrusion of granitoids in Argentine territory. At<br />

this time, the basin’s border expanded and widened considerably.<br />

During the Upper Silurian, the coastal influence is even more<br />

evident; the earliest vascular plants appear, and towards the end of<br />

the cycle, primitive fern and lycophyte forests develop over the<br />

coastal estuaries or ponds.<br />

At the end of the Cordilleran Cycle, the first important tectonic<br />

deformation took place, involving the tacsarian and cordilleran<br />

sequences, the Chiriguano (sensu YPFB) or Eohercynic Phase,<br />

which led to the formation of an orogen. These movements, and the<br />

5

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

la Cordillera hercínica resultante, fueron ampliamante discutidos<br />

por Megard et al. (1973) en una extensa serie de publicaciones. Los<br />

movimientos compresivos, producidos a nivel continental,<br />

ocasionaron el plegamiento de las rocas previas y la formación de<br />

un orógeno hercínico desde la costa pacífica de sudamérica,<br />

pasando por las sierras australes de Buenos Aires, hasta Sudáfrica.<br />

La edad aproximada del metamorfismo de esta deformación en la<br />

Cordillera Oriental Sur, fue medida por Tawackoli et al. (1996)<br />

entre 374 a 317 millones de años.<br />

La cuenca del Ciclo Subandino se desarrolló principalmente en el<br />

borde oriental de la cordillera recién formada, inicialmente con<br />

cañones submarinos al este (grupos Macharetí-Mandiyutí), y<br />

posterior-mente, en el oeste, con facies de plataformas marinas<br />

carbonatadas (Grupo Titicaca).<br />

resulting hercynic cordillere, were discussed largely by Megard et<br />

al. (1973) in an extensive series of publications. The compressive<br />

movements, produced at the continental level, caused the folding of<br />

the previous rocks and the formation of a hercynic orogen from the<br />

Pacific coast in South America, passing by the southern ranges of<br />

Buenos Aires, up to South Africa. The approximate age of this<br />

deformation’s metamorphism in the South of the Eastern Cordillera<br />

was measured by Tawackoli et al. (1996) to be between 374 and<br />

317 millions of years.<br />

The Sub Andean Cycle basin developed mainly on the eastern<br />

border of the recently formed range, initially, with submarine<br />

canyons to the East (Macharetí-Mandiyutí groups), and subsequently<br />

with carbonated marine platform facies to the West<br />

(Titicaca Group).<br />

6

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

Episodio Andino<br />

El Episodio Andino comienza con la disgregación del Gondwana<br />

(ca 200 Ma), que separa Sudamérica de Africa. En este trabajo,<br />

siguiendo la sugerencia de Oller-Veramendi, se reconocen dos<br />

ciclos dentro de este episodio: Andino I y Andino II.<br />

En esa época el Continente de Gondwana experimentó los efectos<br />

de grandes esfuerzos extensionales, e independientemente de la<br />

fractura entre América y Africa, en extensos sectores de <strong>Bolivia</strong>,<br />

especialmente en la actual Cordillera Oriental, se formaron<br />

numerosas cuencas de rift, por lo que el Ciclo Andino I puede<br />

subdividirse en dos fases principales: de Synrift y Postrift. La Fase<br />

Synrift se extiende desde los 200 Ma a partir del Jurásico inferior<br />

con la efusión de coladas basálticas, hasta mediados del Cretácico<br />

superior (ca 80 Ma)<br />

Estos efectos magmáticos fueron producidos por la reactivación de<br />

la antigua fractura de basamento, entre el Cratón de Guaporé y el<br />

Macizo de Arequipa-Huarina. La posición de esa zona de cizalla<br />

correspondería al lineamiento actual de la Cordillera Real (CRFZ).<br />

A causa de la acción compresiva se formó una zona de subducción<br />

verticalizada (Dorbath et al., 1993, Martínez et al., 1996, Dorbath<br />

et al., en prensa) en la que el cratón subduce por debajo del macizo<br />

noraltiplánico. En tiempos hercínicos actuó también como zona de<br />

desgarre compresional.<br />

Con las primeras colisiones de las placas de Aluk y luego la de<br />

Farallón, se produce la formación de los primeros arcos volcánicos.<br />

A partir del Jurásico las secuencias se continentalizan, se forman<br />

cuencas de trasarco con llanuras aluviales, eólicas, fluviales y<br />

lagunares. Durante el Mesozoico el arco volcánico proveé lavas,<br />

cenizas y otros materiales que se intercalan en las secuencias<br />

clásticas. Transgresiones marinas (Formación Miraflores) interrumpen<br />

el depósito continental.<br />

De forma coincidente, los últimos datos demuestran que la etapa<br />

más importante del plegamiento andino (Andino II) se produjo<br />

alrededor de los 26 a 30 Ma [Oligoceno tardío - Mioceno<br />

temprano] (Sempere et al., 1990; Hérail et al., 1994). Esta acción<br />

está ligada a la actividad de la placa pacífica.<br />

La colisión y subducción de la Placa de Nazca produjo una<br />

deformación constante que formó un gran arco volcánico a lo largo<br />

de la costa pacífica de Sudamérica, comprimiendo y plegando<br />

todas las secuencias previas, así como ocasionando un importante<br />

acortamiento de los Andes, formación de cuencas de trasarco,<br />

piggy back, y otras, del Altiplano y sector oeste de la Cordillera<br />

Oriental. Esta acción formó estructuras de vergencia este.<br />

A su vez el Macizo de Arequipa-Huarina fue sobrecorrido sobre el<br />

Cratón de Guaporé, formando estructuras de vergencia oeste por la<br />

acción de la “Zona de Falla de la Cordillera Real” (Dorbath et al.,<br />

1993; Dorbath, et al., en prensa), en la parte este de la Cordillera<br />

Oriental, Subandino y Llanura.<br />

Según Tawackoli et al. (1996), la primera deformación importante<br />

en la Cordillera Oriental Sur se produjo en el Oligoceno inferior,<br />

causando la erosión de la cobertura Cretácico-paleocena. La cuenca<br />

neógena comenzó con un pulso tectónico mayor alrededor de los<br />

Andean Episode<br />

The Andean Episode starts with the breakup of Gondwana (ca. 200<br />

Ma), that severs South America from Africa. In this paper,<br />

following Oller-Veramendi’s suggestion, two cycles are recognized<br />

in this episode: the Andean I and the Andean II.<br />

In this time, the Gondwana Continent experienced the effects of<br />

great extensional stresses. Independently from the fracture between<br />

America and Africa, in extensive sectors of <strong>Bolivia</strong>, specially in the<br />

current Eastern Cordillera, numerous rift basins were formed; thus,<br />

the Andean I Cycle can be subdivided in two main phases: Synrift<br />

and Postrift. The Synrift Phase ranges from 200 Ma, starting with<br />

the Lower Jurassic with the effusion of basaltic flows, to the<br />

middle of the Upper Cretacious (ca. 80 Ma).<br />

These magmatic effects were produced by the reactivation of the<br />

old basement fracture between the Guaporé Craton and the<br />

Arequipa-Huarina Massif. The position of this shear zone would<br />

relate to the current aligment of the Cordillera Real (CRFZ). Due<br />

to the compressive action, a vertical subduction zone was formed<br />

(Dorbath et al., 1993; Martínez et al., 1996; Dorbath et al., in print)<br />

in which the craton subducts underneath the northern Altiplano<br />

massif. In hercynic times, it also acted as a compressive pull-apart<br />

zone.<br />

With the earliest Aluk , and later the Farallón plates collision, the<br />

first volcanic arcs were formed. Starting in the Jurassic, the<br />

sequences become continental, backarc basins with alluvial,<br />

aeolian, fluvial and lagoon plains. During the Mesozoic, the<br />

volcanic arc supplies lava, ashes and other materials that interbed<br />

in the clastic sequences. Sea transgression (Miraflores Formation)<br />

interrupt the continental deposit.<br />

Coincidentally, the lastest date shows that the most important stage<br />

of the Andean folding (Andean II) ocurrred approximately between<br />

26 and 30 Ma [Late Oligocene – Early Miocene] (Sempere et al.,<br />

1990; Hérail et al., 1994). This action is linked to the Pacific<br />

plate´s activity.<br />

The collision and subduction of the Nazca Plate caused a constant<br />

deformation that formed the great volcanic arc along South<br />

America’s Pacific shoreline, compressing and folding all the prior<br />

sequences, as well as producing an important shortening of the<br />

Andes, the formation of backarc, piggy back, and other basins in<br />

the High Plateau and in the western sector of the Eastern Range.<br />

This action formed east-verging structures.<br />

The Arequipa-Huarina Massif, in turn, was thrusted over the<br />

Guaporé Craton, forming west-verging structures by the action of<br />

the “Cordillera Real Fault Zone” (Dorbath et al., 1993; Dorbath et<br />

al., in print), on the eastern part of the Eastern Cordillera, Sub<br />

Andean and Plain.<br />

According to Tawackoli et al. (1996), the first important deformation<br />

in the southern Eastern Cordillera occured during the Lower<br />

Oligocene, causing the erosion of the Cretaceous-Paleocene cover.<br />

The Neogene basin started with a major tectonic pulse around 22<br />

7

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

22 a 24 Ma, y dentro de las cuencas, la deformación compresiva<br />

tiene distintas edades. En Nazareno se registró desde 22 a 12 Ma, y<br />

en Tupiza-Estarca se activaron alrededor de los 17 Ma.<br />

and 24 Ma, and within the basins, the compressive deformation has<br />

various ages. At Nazareno, ages dating back to 22 to 12 Ma were<br />

recorded, and at Tupiza-Estarca, activity started around 17 Ma.<br />

Fig. 1.5 Correlación estratigráfica simplificada del Ciclo Andino II (Oligoceno superior – Reciente)<br />

Simplified stratigraphic correlation of Andean II Cycle (Upper Oligocene – Recent)<br />

Provincias Geológicas<br />

El territorio de <strong>Bolivia</strong>, y coincidiendo aproximadamente con las<br />

regiones morfológicas, se dividió en las siguientes provincias:<br />

Cordillera Occidental, Altiplano, Cordillera Oriental, Sierras<br />

Subandinas, Llanura Chaco-Beniana y Escudo Brasileño.<br />

En los capítulos siguientes no se seguirá estrictamente el<br />

ordenamiento tradicional por provincias. Por el contrario, y con el<br />

objeto de no repetir descripciones estratigráficas, ambientales y<br />

tectónicas se considerarán solo seis capítulos ordenados de la forma<br />

siguiente:<br />

?? Altiplano (incluye de Faja Volcánica o Cordillera Occidental).<br />

?? Cordillera Oriental (incluye el denominado Interandino).<br />

?? Sierras Subandinas (incluye la Llanura Chaqueña).<br />

?? Llanura Beniana (incluye la Llanura Madre de Dios).<br />

?? Llanura Chapare – Boomerang.<br />

?? Cratón de Guaporé.<br />

Geological Provinces<br />

Concurring approximately with the morphological regions, the<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>n territory was divided in the following units: Western<br />

Cordillera, Altiplano, Eastern Cordillera, Subandean Ranges,<br />

Chaco-Beni Plains, and Brazilian Shield.<br />

In the following chapters, the traditional order by provinces will<br />

not be followed strictly. On the contrary, and with the purpose of<br />

avoiding repetitions in stratigraphic, environmental and tectonic<br />

descriptions, only six chapters, arranged in the following order,<br />

will be considered:<br />

?? Altiplano (including de Volcanic Belt or Western Cordillera).<br />

?? Eastern Cordillera (including the so called Interandean).<br />

?? Subandean Ranges (including the Chaco Plain).<br />

?? Beni Plain (including the Madre de Dios Plain).<br />

?? Chapare-Boomerang Plain.<br />

?? Guaporé Craton.<br />

8

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

7<br />

0<br />

50 100 150 200<br />

Kms<br />

Alto Madidi<br />

8<br />

6<br />

9<br />

3<br />

1<br />

Nort<br />

e<br />

2<br />

3b<br />

4<br />

4a<br />

5<br />

3a<br />

Centro<br />

Sur<br />

Fig. 1.6 Provincias Geológicas de <strong>Bolivia</strong> (según YPFB)<br />

1. Cordillera Occidental; 2. Altiplano; 3. Cordillera Oriental: 3a Faja Plegada de Huarina, 3b Inteandino;<br />

4. Subandino, 4a Pie de monte; 5. Llanura del Chaco; 6. Llanura del Beni; 7. Cuenca del Madre de Dios; 8. Plataforma Mojeño-Chiquitana;<br />

9. Cratón del Guaporé.<br />

Geological Provinces of <strong>Bolivia</strong> (after YPFB): 1. Western Cordillera; 2. Altiplano; Eastern Cordillera, 3a Huarina Folded Belt, 3b<br />

Interandean;4. Subandean, 4a Piedmont; 5. Chaco Plain; 6. Beni Plain; 7. Madre de Dios Basin; 8 Mojeño-Chiquitana Platform; 9.<br />

Guaporé Craton<br />

9

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

Agradecimientos<br />

El editor-autor del presente compendio agradece muy sinceramente<br />

a los colegas Claude Martínez, Enrique Díaz Martínez, Jaime Oller<br />

Veramendi, Heberto Pérez Guarachi, Alejandra Dalenz Farjat,<br />

Carlos Oviedo Gómez Sohrab Tawackoli y Margarita Toro de<br />

Vargas, por sus observaciones, correcciones y lectura crítica del<br />

manuscrito. Especial agradecimiento a María Julia Lanza por el<br />

trabajo de traducción al inglés.<br />

Referencias<br />

ALMEIDA, F. F.de, Y. HASUI & B. B. BRITO NEVES, 1976. The<br />

Upper Precambrian of South America.- Bol. Inst. Geocien. Univ.<br />

Sao Paulo, 7 : 45-80.<br />

ANAYA-DAZA, F., J. PACHECO & H. PEREZ, 1987. Estudio<br />

estratigráfico-paleontológico de la Formación Cancañiri en la<br />

Cordillera del Tunari (Departamento de Cochabamba).- IV<br />

Congreso Latinoamericano de Paleontología (Santa Cruz,<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>), II : 679 - 693.<br />

AVILA-SALINAS, W. A., 1991. Eventos tectomagmáticos y<br />

orogénicos de <strong>Bolivia</strong> en el lapso: Proterozoico Inferior a<br />

Reciente.- Revista Técnica de YPFB, 12 (1) : 27-56, Santa Cruz,<br />

Marzo,1991.<br />

AVILA-SALINAS, W. A., 1996. Ambiente tectónico del volcanismo<br />

ordovícico en <strong>Bolivia</strong>.- Memorias del XII Congreso Geológico de<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong> (Tarija) : 137-143.<br />

BAHLBURG, H., 1990. The Ordovician basin in the Puna of NW<br />

Argentina and N Chile. Geodynamic evolution from back arc to<br />

foreland basin.- Geotektonische Forschungen, 75 : 1-107.<br />

BAHLBURG, H. & F. HERVE, 1995. Tectonostratigraphic terranes<br />

and geodynamic evolution of northwestern Argentina and<br />

northern Chile.- (in: Laurentian-Gondwanan conections before<br />

Pangea. Field Conference Programs with Abstracts) : 6. IGCP<br />

Project 376. Jujuy, october 1995<br />

DALLA SALDA, L. H., I. W. D. DALZIEL, C. A. CINGOLANI &<br />

R. VARELA, 1992. Did the Taconic Appalachians continue into<br />

sourthern South America?.- Geology, 20 : 1059-1062.<br />

DALZIEL, I. W. D., 1991. Pacific margins of Laurentia and East<br />

Antarctica-Australia as a conjugate rift pair: Evidence and<br />

implications for an Eocxambrian supecontinent.- Geology, 19 :<br />

598-601.<br />

DALZIEL, I. W. D., 1993. Tectonic tracers and the origin of the<br />

Proto-Andean Margin.- XII Congreso Geológico Argentino y II<br />

Congreso de Exploración de Hidrocarburos. Actas III : 367-374.<br />

DALZIEL, I. W. D., 1997. Neoproterozoic-Paleozoic geography and<br />

tectonics: Review, hypothesis, enviromental speculation.-<br />

Geological Society of America Bulletin, 109 (1) : 16-42.<br />

DIAZ-MARTINEZ, E., 1992. Inestabilidad tectónica en el Devónico<br />

superior del Altiplano de <strong>Bolivia</strong>: Evidencias en el registro<br />

sedimentario.- Actas VIII Congreso Latinoamericano de Geología<br />

Acknowledgements<br />

The author-editor of this compendium would like to express his<br />

sincere thanks to his colleagues Claude Martínez, Enrique Díaz<br />

Martínez, Jaime Oller Veramendi, Herberto Pérez Guarachi,<br />

Alejandra Dalenz Farjart, Carlos Oviedo Gómez, Sohrab<br />

Tawackoli and Margarita Toro de Vargas, for their remarks,<br />

corrections and critical reading of the manuscript. Special thanks to<br />

María Julia Lanza for the english translation work.<br />

References<br />

y III Congreso Geol. de España, Vol. 4 : 35-39, Salamanca,<br />

España, Junio 1992.<br />

DIAZ, E., R. LIMACHI, V. H. GOITIA, D. SARMIENTO, O.<br />

ARISPE & R. MONTECINOS, 1996. Inestabilidad tectónica<br />

relacionada con el desarrollo de la cuenca de antepaís paleozoica<br />

de los Andes centrales de <strong>Bolivia</strong>.- Anais du Simpósio Sul<br />

Americano do Siluro-Devoniano, Estratigrafia e Paleontologia :<br />

299- 308. Ponta Grossa, Brasil.<br />

DIAZ, E., R. LIMACHI, V. H. GOITIA, D. SARMIENTO, O.<br />

ARISPE & R. MONTECINOS, 1996a. Relación entre tectónica<br />

y sedimentación en la cuenca de antepaís del Paleozoico medio<br />

de los Andes centrales de <strong>Bolivia</strong> (14 a 22° S).- Memorias del<br />

XII Congreso Geológico de <strong>Bolivia</strong>, I : 97-102, Tarija.<br />

GOLONKA, J., M. I. ROSS & C. R. SCOTESE, 1994. Phanerozoic<br />

paleogeographic and paleoclimatic modeling maps.- (in: Embry,<br />

A., B. Beauchamp & J. Glass (eds.), Pangea Global<br />

environments and resources. Canadian Society of Petroleum<br />

Geologists, Memoir 17 : 1-47.<br />

GOHRBANDT, K. H. A., 1992. Paleozoic paleogeographic and<br />

depositional developments on the central proto-Pacific margin<br />

of Gondwana: Their importance to hydrocarbon accumulation.-<br />

Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 6 (4) : 267-287.<br />

GRUNOW, A., R. HANSON & T. WILSON, 1996. Were aspects of<br />

Pan-African deformation linked to Iapetus opening?.- Geology,<br />

24 (12) : 1063-1066.<br />

HERAIL, G., P. BABY & P. SOLER, 1994. El contacto Cordillera<br />

Oriental-Altiplano en <strong>Bolivia</strong>: Evolución tectónica, sedimentaria<br />

y geomorfológica durante el Mioceno.- 7° Congreso Geológico<br />

Chileno, I : 62-66, Concepción.<br />

ISAACSON, P. E. & E. DIAZ-MARTINEZ, 1995. Evidence for a<br />

middle-late Paleozoic foreland basin and significant paleolatitudinal<br />

shift, central Andes.- (in: A. J. Tankard, R. Suárez S. & H.<br />

J. Welsink, Petroleum Basins of South America, AAPG Memoir<br />

62 ) : 231-249.<br />

LITHERLAND, M. & K. BLOOMFIELD, 1981. The Proterozoic<br />

history of Eastern <strong>Bolivia</strong>.- Precambrian Research, 15 : 157-179,<br />

Elsevier Sci.Publ.Co., Amsterdam.<br />

LITHERLAND, M., B. A. KLINCK, E. A. O'CONNOR & P.E.J.<br />

PITFIELD, 1985. Andean-trending mobile belts in the Brazilian<br />

Shield.- Nature, 314 (6009) : 345-348, March/85<br />

10

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

MARTINEZ, Cl., C. DORBATH & A. LAVENU, 1996. La cuenca<br />

subsidente cenozoica noraltiplánica y sus relaciones con una<br />

subducción transcurrente continental.- Memorias del XII<br />

Congreso Geológico de <strong>Bolivia</strong>, I : 3-28, Tarija.<br />

MENELEY ENTERPRICES LTDA, 1991. Proyecto cooperativo de<br />

estudios de hidrocarburos en cuencas subandinas: Informe del país<br />

- <strong>Bolivia</strong>.- Documento inédito preparado para Petro-Canada,<br />

Arpel y Banco Mundial, mayo de 1991.<br />

MORALES-SERRANO, G., 1997. Nuevos datos geocronológicos y<br />

bioestratigráficos del Macizo antiguo de Arequipa.- IX<br />

Congreso Peruano de Geologia. Resúmenes Extendidos,<br />

Sociedad Geológica del Perú, vol. Esp. 1 (1997) : 365-369.<br />

MUKASA, S. B. & D. J. HENRY, 1990. The San Nicolás batholith<br />

of coastal Perú: early Palaeozoic continental arc or continental<br />

rift magmatism.?- Journal of the Geological Society, London,<br />

147 : 27-39.<br />

OLLER-VERAMENDI, J., 1992. Cuadro cronoestratigráfico de<br />

<strong>Bolivia</strong>.- Publicación especial de YPFB-GXG, Santa Cruz.<br />

RAMOS, V. A., 1997. The early Paleozoic protomargin of South<br />

America: a conjugate passive margin of Laurentia?.- XIV Reunião<br />

de Geologia do Oeste Peninsular. Reunião anual do PICG-376 :<br />

5-10, Vila Real-Portugal.<br />

RÖSSLING, R. & R. BALLON-AYLLON, 1996. Geología de los<br />

Andes Centrales.- (en: B.Troëng, et al. (eds.) Mapas temáticos<br />

de Recursos Minerales de <strong>Bolivia</strong>. Hoja Camargo). Boletín del<br />

Servicio Geológico de <strong>Bolivia</strong>, 8 : 27-71, La Paz.<br />

SEMPERE, T., 1995. Phanerozoic evolution of <strong>Bolivia</strong> and adjacent<br />

regions.- (in: A. J. Tankard, R. Suárez S. & H. J. Welsink,<br />

Petroleum Basins of South America : AAPG Memoir 62 ) :<br />

207-230.<br />

SEMPERE, T., G. HERAIL & J. OLLER, 1988. Los aspectos<br />

estructurales y sedimentarios del oroclino boliviano.- V<br />

Congreso Geológico Chileno, I : A127-A142, Santiago.<br />

STEINMANN, G., 1929. Geologie von Peru.- Heidelberg, Carl<br />

Winters Universitätabuchandlung, 448 p.<br />

SUAREZ-SORUCO, R., 1982. El límite Devónico - Carbónico en la<br />

cuenca sudoriental de <strong>Bolivia</strong>.- IGCP-Proj. 42, Resumo de<br />

Contribuiçoes : 6, Sao Paulo.<br />

SUAREZ-SORUCO, R., 1983. Síntesis del desarrollo estratigráfico<br />

y evolución tectónica de <strong>Bolivia</strong> durante el Paleozoico Inferior.-<br />

Revista Técnica de YPFB, 9 (1-4) : 223-228, La Paz.<br />

SUAREZ-SORUCO, R., 1989. Desarrollo tectosedimentario del<br />

Paleozoico Inferior de <strong>Bolivia</strong>.- Información Geológica<br />

U.A.T.F., II : 1-11 Simposio Geológico Bodas de Plata (1984)<br />

Universidad Tomás Frías, Potosí.<br />

SUAREZ-SORUCO, R., 1999. <strong>Bolivia</strong>: Late Proterozoic–Early<br />

Paleozoic.- 4 th International Symposium on Andean Geodynamics<br />

(ISAG/99), Göttingen, Alemania. (en prensa)<br />

TAWACKOLI, S., J. KLEY & V. JACOBSHAGEN, 1996.<br />

Evolución tectónica de la Cordillera Oriental del sur de <strong>Bolivia</strong>.-<br />

XII Congreso Geológico de <strong>Bolivia</strong>, I : 91-96, Tarija.<br />

WASTENEYS, H. A., A. H. CLARK, E. FARRAR & R. J.<br />

LANGRIDGE, 1995. Grenvillian granulite-facies metamorphism<br />

in the Arequipa Massif, Peru: a Laurentia-Gondwana<br />

link.- Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 132 (1995) : 63-73<br />

11

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

EDA<strong>DE</strong>S<br />

MADRE <strong>DE</strong> DIOS<br />

SUBANDINO NORTE<br />

FAJA PLEGADA<br />

<strong>DE</strong> HUARINA<br />

FAJA ANDINA<br />

SUBANDINA SUR<br />

JURASICO INF.<br />

TIQUINA<br />

CICLO SUBANDINO<br />

TRIASICO<br />

PERMICO<br />

CARBONIFERO<br />

SUPERIOR<br />

CARBONIFERO<br />

MEDIO<br />

BOPI<br />

COPACABANA<br />

GRUPO TITICACA<br />

CHUTANI<br />

MBRO. SAN PABLO<br />

MBRO. COLLASUYO<br />

COPACABANA<br />

YAURICHAMBI<br />

COPACABANA<br />

GRUPO CUEVO<br />

GRUPO<br />

MANDIYUTI<br />

GRUPO<br />

MACHARETI<br />

CICLO CORDILLERANO<br />

EDA<strong>DE</strong>S<br />

MADRE <strong>DE</strong> DIOS<br />

SUBANDINO NORTE<br />

FAJA PLEGADA<br />

<strong>DE</strong> HUARINA<br />

FAJA ANDINA<br />

SUBANDINA SUR<br />

SERPUKHOVIANO<br />

FAMENIANO GRUPO RETAMA GRUPO AMBO SAIPURU<br />

FRASNIANO<br />

GIVETIANO<br />

EIFELIANO<br />

EMSIANO<br />

PRAGIANO<br />

LOCHKOVIANO<br />

PRIDOLIANO<br />

LUDLOVIANO<br />

WENLOCKIANO MED<br />

WENLOCKIANO INF<br />

LLANDOVERIANO<br />

ASHGILLIANO SUP.<br />

TOMACHI<br />

TEQUEJE<br />

RIO CARRASCO<br />

COLLPACUCHO<br />

SICASICA<br />

BELEN<br />

VILA VILA<br />

CATAVI<br />

UNCIA<br />

LLALLAGUA<br />

HUANUNI<br />

CANCAÑIRI<br />

IQUIRI<br />

LOS MONOS<br />

HUAMAMPAMPA<br />

ICLA<br />

SANTA ROSA<br />

TARABUCO<br />

KIRUSILLAS<br />

CANCAÑIRI<br />

CALIZA SACTA<br />

FAJA BOOMERANG<br />

ROBORE<br />

LIMONCITO<br />

ROBORE<br />

EL CARMEN<br />

?<br />

EDA<strong>DE</strong>S<br />

MADRE <strong>DE</strong> DIOS<br />

SUBANDINO<br />

NORTE<br />

FAJA PLEGADA<br />

<strong>DE</strong> HUARINA<br />

NORTE<br />

SUR<br />

NORTE<br />

FAJA ANDINA<br />

SUBANDINA SUR<br />

SUR<br />

CICLO TACSARIANO<br />

AHSGILLIANO INF.<br />

CARADOCIANO<br />

TARENE<br />

ENA<strong>DE</strong>RE<br />

TOKOCHI<br />

AMUTARA<br />

TAPIAL A & B<br />

KOLLPANI<br />

ANGOSTO<br />

MARQUINA<br />

SAN BENITO<br />

ANZALDO<br />

LLANVIRNIANO ? COROICO CAPINOTA<br />

ARENIGIANO<br />

TREMADOCIANO<br />

CAMBRICO<br />

SUPERIOR<br />

PIRCANCHA / SELLA<br />

AGUA Y TORO<br />

OBISPO<br />

CIENEGUILLAS<br />

ISCAYACHI<br />

SAMA<br />

TOROHUAYCO<br />

CAMACHO<br />

Fig. 1.7 Subdivisión en Dominios Tectono-Estratigráficos para los ciclos Tacsariano, Cordillerano y Subandino<br />

12

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

Capítulo 2<br />

(FAJA VOLCANICA Y ALTIPLANO)<br />

(VOLCANIC BELT AND ALTIPLANO)<br />

Introducción<br />

En este capítulo se desarrolla de forma conjunta la denominada<br />

Cordillera Occidental o Faja Volcánica Occidental, y el Altiplano.<br />

Este agrupamiento se hace considerando que ambas regiones<br />

pueden recibir un mismo tratamiento. Sin embargo en el texto, se<br />

diferencian estas dos áreas como Altiplano Occidental y<br />

Altiplano Oriental.<br />

En el trabajo se divide el Altiplano en las tres regiones geográficas<br />

en las que tradicionalmente es separado: Altiplano Norte,<br />

Altiplano Centro y Altiplano Sur (Fig. 1.6), y en cada uno de<br />

estos subcapítulos se desarrolla una síntesis estratigráfica de forma<br />

independiente, siguiendo un ordenamiento cronológico por ciclos<br />

tectosedimentarios.<br />

El Altiplano es una extensa cuenca intramontana de aproximadamente<br />

110.000 km 2 , formada en el Cenozoico, a partir del<br />

comienzo del levantamiento de la Cordillera Oriental.<br />

En general, en el Altiplano existe un control estructural sobre el<br />

relieve, ya que los anticlinales se encuentran formando serranías y<br />

los sinclinales concuerdan con valles y zonas topográficamente<br />

bajas. Gran parte del Altiplano forma extensas superficies<br />

niveladas, cubiertas por depósitos lagunares, glaciales y aluviales<br />

recientes, situadas entre 3.600 y 4.100 metros sobre el nivel del<br />

mar. Esta meseta se halla interrumpida por serranías aisladas,<br />

cuyas alturas varían entre 4.000 y 5.350 m.s.n.m.<br />

Desde el punto de vista geomorfológico, representa una extensa<br />

depresión interandina de relleno, controlada tectónicamente por<br />

bloques hundidos y elevados, tanto transversal como longitudinalmente,<br />

con una evolución compleja y un fuerte reajuste<br />

morfogenético andino (Araníbar, 1984). La región posee una red de<br />

drenaje endorreica, con extensos salares como el de Uyuni y<br />

Coipasa al sur, y grandes lagos como el Titicaca y Poopó al norte.<br />

El clima es árido hacia el sur y semiárido hacia el norte.<br />

La formación del Altiplano se inicia en el Paleoceno-Eoceno con el<br />

sobrecorrimiento del Macizo de Arequipa-Huarina sobre el Cratón<br />

de Guaporé, por medio de la sutura intracratónica ubicada debajo<br />

de la Cordillera Real, y reflejada en superficie en la Zona de Fallas<br />

de la Cordillera Real (Martínez et al., 1996). Este sobrecorrimiento<br />

Introduction<br />

The so-called Western Cordillera or Western Volcanic Belt, and<br />

the Altiplano are discussed jointly in this chapter. This association<br />

is made taking into consideration that both regions could be treated<br />

similarly. In the text, however, these two areas are distinguished as<br />

Western Altiplano and Eastern Altiplano.<br />

This paper divides the Altiplano in the three geographical regions<br />

in which it is traditionally done: the North Altiplano, the Central<br />

Altiplano and the South Altiplano (Fig. 1.6), and each of the<br />

subchapters will contain an independent stratigraphic synthesis<br />

following a chronological order by tecto-sedimentary cycles.<br />

The Altiplano is an extensive intramontane basin of approximately<br />

110,000 km 2 , formed during the Cenozoic, starting with the<br />

beginning of the uplifting of the Eastern Cordillera.<br />

Generally speaking, in the Altiplano there is a structural control<br />

over the relief, since the anticlines form mountain ranges and the<br />

synclines conform with the valleys and topographically low areas.<br />

A major part of the Altiplano forms extensive levelled surfaces,<br />

covered by recent lagoon, glaciar and alluvial deposits, located<br />

between 3,600 and 4,100 meters above sea level. This plateau is<br />

interrupted by isolated ranges with elevations ranging between<br />

4,000 and 5,350 masl.<br />

From the morphological point of view, it is an extensive<br />

interandean infill sag, controlled tectonically by both sidewise and<br />

lengthwise sinking and elevated blocks, with a complex evolution<br />

and a strong Andean morphogenetic readjustment (Aranibar, 1984).<br />

The region has a endorreic drainage network, with extensive<br />

salinas such as the Uyuni and Coipasa salars to the South, and great<br />

lakes, such as the Titicaca and Poopó Lakes to the North. In the<br />

South, the climate is dry, and semi-dry in the North.<br />

The formation of the Altiplano started during the Paleocene-<br />

Eocene with the thrust of Arequipa-Huarina Massif over the<br />

Guaporé Craton, through a intercratonic suture located beneath the<br />

Cordillera Real, and reflected at the surface on Cordillera Real<br />

Fault Zone (Martínez et al., 1996). This overthrust originated the<br />

13

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

originó el acortamiento progresivo de las cuencas altiplánicas. El<br />

acortamiento fue aparentemente continuo, sin etapas intermedias de<br />

distensión. Los grandes eventos Incaico, Quechua, y otros,<br />

solamente son el reflejo de etapas de máxima compresión<br />

(Martínez et al., 1996).<br />

El Precámbrico y Paleozoico actúan como un basamento sísmico<br />

fácilmente interpretable sin lograr su diferenciación por sistemas.<br />

La cobertura del basamento está conformada por rocas del<br />

Cretácico, Paleógeno y Neógeno, a su vez afectada por pliegues y<br />

fallas, que en varios sectores del Altiplano pueden ser excelentes<br />

trampas petrolíferas (Araníbar et al., 1995).<br />

progressive shortening of the Altiplano’s basins. Apparently, it was<br />

an on-going shortening without intermediate distension stages. The<br />

Incaic, Quechua and other great events are only the reflection of<br />

stages of maximum contraction (Martínez et al., 1996).<br />

The Precambrian and Paleozoic act as a seismic basement that can<br />

be easily interpreted without achieving a system differentation.<br />

The basement’s cover is made up by Cretaceous, Paleogene and<br />

Neogene rocks, and affected in turn by folds and faults, which, in<br />

several sectors of the Altiplano, could be excellente oil traps<br />

(Aranibar et al., 1995).<br />

En el sector norte, la falla San Andrés marca aproximadamente el<br />

límite entre el Altiplano Oriental y el Occidental. Al este, el<br />

contacto con la Cordillera Oriental está dado por la falla Coniri<br />

(Hérail et al., 1994).<br />

Proterozoico<br />

Las rocas más antiguas descritas en el Altiplano Norte,<br />

equivalentes a los eventos del Ciclo Sunsás del Cratón de Guaporé,<br />

corresponden a los metagranitos del basamento perforado por el<br />

pozo de San Andrés. La perforación exploratoria realizada por la<br />

compañía Superior Oil en el pozo San Andrés de Machaca (SAS-<br />

2), 50 km al sur del Lago Titicaca, perforó este basamento a una<br />

profundidad de 2.745 a 2.814 m. Este cuerpo forma parte del<br />

Macizo de Arequipa-Huarina, el cual constituye el basamento<br />

cristalino de la franja occidental de los Andes Centrales. La edad<br />

asignada (1050 ± 100 Ma por Rb-Sr), sería equivalente a la<br />

orogenia sunsasiana del oriente boliviano. Se estableció además<br />

que estas rocas fueron afectadas por un evento metamórfico<br />

posterior (530 ± 30 Ma), equivalente a la orogenia brasiliana<br />

(Lehmann, 1978).<br />

Otro grupo de afloramientos en el Altiplano, cuya edad y génesis<br />

aún no ha sido definida con certeza, corresponde a los afloramientos<br />

del Cerro Chilla, ubicado al sur del Lago Titicaca. Estas<br />

rocas están constituidas por una diversidad de litologías que<br />

indican depósitos marinos profundos como turbiditas, lavas<br />

almohadilladas de composición basáltica, flujos de detrito, y otras.<br />

Según GEOBOL (1995: Hoja Jesús de Machaca) el Complejo<br />

Chilla está conformado por cuarcitas y pizarras, así como por<br />

arcosas, lutitas, lavas basálticas, y sills doleríticos. Estas rocas<br />

fueron descritas por vez primera por Cherroni (1973), y desde esa<br />

fecha les han sido atribuidas diferentes edades (Proterozoico,<br />

Paleozoico, Jurásico, etc.). Oller, 1996; Araníbar et al, 1997 y otros<br />

les atribuyen una edad Vendiano terminal a Cámbrico inferior. Sin<br />

embargo, Díaz-Martínez (1996) sugiere una edad ordovícica para<br />

esta secuencia.<br />

Probablemente, las rocas proterozoicas estuvieron aflorando en el<br />

borde occidental del Altiplano durante el Mioceno y el Plioceno.<br />

Remanentes de esas rocas están ahora conservadas en los depósitos<br />

neógenos, como clastos dentro de las formaciones Azurita, Mauri y<br />

Pérez.<br />

In the northern sector, the San Andrés Fault approximately marks<br />

the limit between the Eastern and Western Altiplano. To the East,<br />

the Coniri fault determines the contact with the Eastern Cordillera<br />

(Hérail et al., 1994).<br />

Proterozoic<br />

Equivalent to the events of the Sunsás Cycle in the Guaporé<br />

Craton, the oldest rocks described in the North Altiplano are<br />

metagranites of the basement drilled by the San Andrés well. The<br />

exploratory drilling carried out by the Superior Oil Company at the<br />

San Andrés of Machaca well (SAS-2), 50 km south of Lake<br />

Titicaca, bored this basement at a depth between 2,745 and 2,814<br />

m. This body is part of the Arequipa-Huarina Massif that makes up<br />

the crystalline basement of the western strip of the central Andes.<br />

The age assigned (1050 ± 100 Ma by Rb-Sr) would be equal to the<br />

Sunsás orogeny of Eastern <strong>Bolivia</strong>. It was established as well that<br />

these rocks were affected by a later metamorphic event (530 ± 30<br />

Ma), equivalent to the Brazilian orogeny (Lehmann, 1978).<br />

Another group of outcrops in the Altiplano, the age and genesis of<br />

which has not yet been defined with certainty, refers to the Cerro<br />

Chilla outcrops, located south of Lake Titicaca. These rocks are<br />

made up by a diversity of lithologies that indicate deep marine<br />

deposits, such as turbidites, basaltic pillow lavas, detritus flows,<br />

and others. According to GEOBOL (1995: Jesús de Machaca<br />

Sheet), the Chilla Complex is made up by quartzites and slates, as<br />

well as by arkoses, shale, basaltic lavas and doleritic sills. These<br />

rocks were first described by Cherroni (1973), and have, ever since,<br />

been ascribed different ages (Proterozoic, Paleozoic, Jurassic, etc.).<br />

Oller, 1996; Araníbar et al., 1997 and others ascribe them a Late<br />

Vendian to Lower Cambrian age. However, Díaz-Martínez (1996)<br />

suggests a Ordovician age for this sequence.<br />

The Proterozoic rocks probably outcropped on the western border<br />

of the Altiplano during the Miocene and Pliocene. Remnants of<br />

these rocks are now kept in Neogene deposits, such as boulders<br />

within the Azurita, Mauri and Pérez formations.<br />

14

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

Ciclo Tacsariano<br />

No se han descrito afloramientos ordovícicos en el sector norte del<br />

Altiplano boliviano, no obstante son frecuentes en territorio<br />

peruano al noroeste del Lago Titicaca. Sin embargo, como se<br />

indica en el acápite anterior, no se debe descartar la posibilidad de<br />

que los afloramientos del Cerro Chilla, Jesús de Machaca y<br />

Caquiaviri, considerados a la fecha como precámbricos, correspondan<br />

al Ordovícico (Díaz-Martínez, 1996).<br />

En el pozo Santa Lucía-X1, por debajo de una cubierta cenozoicacretácica<br />

de 1900 m, fueron recolectadas muestras de lutitas con<br />

graptolites llanvirniano-caradocianos (Dalenz, 1996). Las rocas<br />

ordovícicas del pozo Santa Lucía están sobremaduradas, y<br />

presentan intercalaciones de lava intruídas en forma de sills.<br />

En el pozo Toledo-X1, por debajo de las rocas de la Formación<br />

Tiahuanacu, se reportaron sedimentos tacsarianos a partir de los<br />

3760 m de profundidad. Estas rocas contienen una asociación de<br />

palinomorfos del Ordovícico superior, representados por<br />

Vellosacapsula setosapellicula cuyo rango conocido es<br />

Caradociano - Ashgilliano superior (Exxon, 1995).<br />

Ciclo Cordillerano<br />

No han sido citados sedimentos de la Formación Cancañiri en el<br />

Altiplano Norte. La secuencia del Ciclo Cordillerano se inicia en<br />

esta área con algunos afloramientos de areniscas turbidíticas de la<br />

Formación Llallagua (Koeberling, 1919), de posible edad<br />

wenlockiana.<br />

En el subsuelo de este sector se reportaron rocas silúricas y<br />

devónicas, o sólo devónicas como por ejemplo en el pozo La Joya<br />

(Formación Belén).<br />

Ciclo Andino<br />

En este compendio se tomarán en cuenta dos subdivisiones para el<br />

Ciclo Andino. El Ciclo Andino I, que comprende a los sedimentos<br />

depositados entre el Jurásico y el Oligoceno inferior, considerando<br />

por lo tanto a las formaciones Chaunaca, El Molino, Santa Lucía y<br />

Tiahuanacu del sector oriental, y Berenguela del Altiplano Occidental.<br />

El Ciclo Andino II, se inicia en el Oligoceno superior-<br />

Mioceno inferior y continúa hasta el Reciente. Están incluidos en<br />

este segundo ciclo las formaciones Coniri, Kollu Kollu, Caquiaviri,<br />

Rosapata, Topohoco, San Andrés, Pomata, Umala y Ulloma del<br />

sector oriental, y la secuencia del Altiplano Occidental: Mauri<br />

inferior, Mauri superior, Abaroa, Cerke, Pérez y Charaña.<br />

Los movimientos producidos entre estos dos ciclos corresponden a<br />

la Fase Incaica que representa solamente un momento paroxismal<br />

de las fuerzas compresivas que produjeron el acortamiento andino.<br />

Ciclo Andino I<br />

La unidad más antigua de este ciclo corresponde a la Formación<br />

Chaunaca (Lohmann & Branisa, 1962), depositada en un ambiente<br />

continental con influencia marina de plataforma somera. La unidad<br />

Tacsarian Cycle<br />

No ordovician outcrops have been described in the northern sector<br />

of the <strong>Bolivia</strong>n Altiplano; however, such outcrops are common in<br />

Peruvian territory, northeast of Lake Titicaca. Nonetheless, as<br />

mentioned in the paragraph above, the possibility of the Cerro<br />

Chilla, Jesús de Machaca and Caquiaviri outcrops, which are<br />

currently considered as Precambrian, actually relating to the<br />

Ordovician, cannot be dismissed (Díaz-Martínez, 1996).<br />

At the Santa Lucía-X1 well, beneath a Cenozoic-Cretaceous cover<br />

of 1900 m, lutite samples with Llanvirnian-Caradocian graptolites<br />

were collected (Dalenz, 1996). The Ordovician rocks at Santa<br />

Lucía well are overaged and display lava interbedding intruded as<br />

sills.<br />

At the Toledo-X1 well, beneath the Tiahuanacu Formation rocks,<br />

Tacsarian sediments starting at a depth of 3760 m were reported.<br />

These rocks contain an association of Upper Ordovician<br />

palynomorphs, represented by Vellosacapsula setosapellicula, the<br />

known range of which is Caradocian – Upper Ashgillian (Exxon,<br />

1995).<br />

Cordilleran Cycle<br />

No Cancañiri Formation sediments have been quoted on the North<br />

Altiplano. In this area, the Cordilleran Cycle sequence starts with<br />

some turbiditic sandstone outcrops of the Llallagua Formation<br />

(Koeberling, 1919), possible of wenlockian age.<br />

In this sector’s subsurface, Silurian and Devonian, or only Devonian<br />

rocks have been reported, such as those at the La Joya welll<br />

for instance (Belén Formation).<br />

Andean Cycle<br />

This compendium will consider two subdivisions for the Andean<br />

Cycle. The Andean I Cycle, consisting of the sediments deposited<br />

between the Jurásico and the Lower Oligocene, thus including the<br />

Chaunaca, El Molino, Santa Lucía and Tiahuanacu formations in<br />

the eastern sector, and the Berenguela formation in the western<br />

Altiplano. The Andean II Cycle starts in the Upper Oligocene-<br />

Lower Miocene and continues up to the Recent. This second cycle<br />

includes the Coniri, Kollu Kollu, Caquiaviri, Rosapata, Topohoco,<br />

San Andrés, Pomata, Umala and Ulloma formations, in the western<br />

sector, and the western Altiplano sequence: lower Mauri, Upper<br />

Mauri, Abaroa, Cerke, Pérez and Charaña.<br />

The movements produced between these two cycles relate to the<br />

Incaic Phase, representing only a paroxysmal moment of the<br />

compressive forces that produced the Andean shortening.<br />

Andean I Cycle<br />

The oldest unit in this cycle pertains to the Chaunaca Formation<br />

(Lohmann & Branisa, 1962), deposited in a continental environment<br />

with shallow platform marine influence. The unit is made up<br />

15

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

está constituida por limolitas y lutitas lacustres, intercaladas con<br />

delgadas capas de calizas. La secuencia es fosilífera, en ella se<br />

encontraron ostrácodos, conchostracos y pelecípodos como<br />

Brachidontes aff. fulpensis y restos de peces. Esta fauna indica una<br />

edad cretácica superior (Santoniano-Campaniano).<br />

A fines del Cretácico, durante el Maastrichtiano se deposita en la<br />

misma cuenca de trasarco la Formación El Molino (Lohmann &<br />

Branisa, 1962), constituida en la base por areniscas, y luego por<br />

calizas, margas gris verdosas, areniscas calcáreas. Estas rocas<br />

fueron depositadas en un ambiente de plataforma carbonatada<br />

proximal, lagunar y costero, con influencia marina. Esta unidad es<br />

muy fosilífera, están presentes algas estromatolíticas (Pucalithus),<br />

moluscos, y sobre todo es remarcable la abundancia de restos de<br />

peces fósiles y huesos de reptiles.<br />

Durante el Paleógeno en el Altiplano Norte se deposita la<br />

Formación Santa Lucía (Lohmann & Branisa, 1962). En<br />

Andamarca y San Pedro de Huaylloco (Jarandilla, 1988), la base se<br />

halla compuesta por areniscas conglomerádicas, que pasan a<br />

margas multicolores, limolitas y arcillas. Esta secuencia se depositó<br />

en un ambiente continental de tipo fluvial (ríos meandrantes en<br />

facies de llanura de inundación) y lagunas someras.<br />

En la Hacienda Azafranal el pase de la Formación Santa Lucía a la<br />

Formación Tiahuanacu es aparentemente transicional. Sin<br />

embargo, en la mayoría de las localidades esta relación es<br />

discordante sobre las rocas precedentes, especialmente cretácicas.<br />

by silt and lacustrine shale, interbedded with thin limestone layers.<br />

It is fossiliferous sequence where ostracodes, chonchostraca and<br />

pelecipods such as Brachidontes aff. fulpensis and fish remanents<br />

have been found. This fauna indicates a Upper Cretaceous age<br />

(Santonian-Campanian).<br />

At the end of the Cretaceous, during the Maastrichtian, the El<br />

Molino Formation deposited in the same backarc basin (Lohmann<br />

& Branisa, 1962). At its base, this formation is made up by<br />

sandstones, and then by limestones, greenish gray marl, and<br />

calcareous sandstones. These rocks were deposited in a proximal,<br />

lagoon and coastal carbonated platform environment with marine<br />

influence. This unit is very fossiliferous, displaying stromatolitic<br />

algae (Pucalithus), molluscs, and above all, the abundance of fossil<br />

fish remanents and reptilian bones is remarkable.<br />

During the Paleogene, the Santa Lucía Formation deposited in the<br />

North Altiplano (Lohmann & Branisa, 1962). At Andamarca and<br />

San Pedro de Huaycollo (Jarandilla, 1988), the base is made up by<br />

conglomerate sandstones changing to multicolor marls, silts and<br />

clays. This sequence deposited in a fluvial-type and shallow<br />

lagoons continental environment (meandering rivers in a flood<br />

plain facies).<br />

At Hacienda Azafranal, the passing from the Santa Lucía<br />

Formation to the Tiahuanacu Formation is apparently transitional.<br />

Nontheless, in the majority of the locations, there is an<br />

unconforming relationship to the preceding rocks, particularly the<br />

Cretaceous ones.<br />

16

<strong>COMPENDIO</strong> <strong>DE</strong> <strong>GEOLOGIA</strong> <strong>DE</strong> BOLIVIA<br />

17

REVISTA TECNICA <strong>DE</strong> YPFB VOL. 18 (1-2) JUNIO 2000<br />

Aproximadamente en esta época se formaron capas de yeso y<br />

arcilitas yesíferas varicolores de la Formación Jalluma (Ascarrunz<br />

et al., 1967), que en opinión de García-Duarte & García (1995)<br />

ascendieron como diapiros durante el Eoceno-Mioceno, siguiendo<br />

lineamientos que reflejan antiguas fallas normales como resultado<br />

de la presión litostática y esfuerzos compresivos contemporáneos.<br />

A partir de la Formación Tiahuanacu (Ascarrunz, 1963),<br />

depositada durante el Eoceno, el área de relleno cambia a una<br />

cuenca de antepaís de la Cordillera Oriental, en la que se forma una<br />

llanura fluvial rellena por una potente secuencia de más de 3.000 m<br />

de espesor de areniscas, limolitas y arcilitas rojizas, en las que<br />

intercalan delgados lentes conglomerádicos con restos<br />

carbonizados y cupritizados de plantas fósiles (Cherroni, 1974).<br />

Hacia el tope de la secuencia se depositan horizontes volcánicos.<br />

Estas rocas fueron depositadas durante el Eoceno y el Oligoceno<br />

inferior. Swanson et al. (1987) obtuvieron de las areniscas<br />

volcánicas de la parte alta de esta unidad edades de 29.2 ± 0.8 y<br />

29.6 ± 0.8 Ma (Oligoceno inferior alto).<br />

Un equivalente lateral de la Formación Tiahuanacu es la Formación<br />

Ballivián (Ascarrunz et al., 1967), depositada en una planicie<br />

fluvio-lacustre. La unidad está compuesta por 500 m de arcilitas<br />

varicoloreadas, intercaladas con areniscas y arcilitas yesíferas gris<br />

verdosas. Le suprayacen en discordancia las formaciones Coniri y<br />

Kollu Kollu.<br />

Formando farellones escarpados se presentan en la zona occidental<br />

del Altiplano (área de Charaña) los sedimentos más antiguos de la<br />

región. Corresponden a la Formación Berenguela (Sirvas, 1964;<br />

Sirvas & Torres, 1966), y están constituidos por aproximadamente<br />

200 m de areniscas conglomerádicas, areniscas arcósicas<br />

compactas, grano- crecientes, de color rojo amarillento, que luego<br />

van adquiriendo una tonalidad más roja hasta llegar al tope, donde<br />

forman una costra dura, formada por areniscas cuarcíticas. La edad<br />

está inferida por dataciones efectuadas por Evernden et al. (1966)<br />

en un horizonte arenoso con glauconita de la parte inferior de la<br />

Formación San Andrés, datada en 38 Ma (Eoceno superior)<br />

Ciclo Andino II<br />

Este ciclo se inicia en el límite Oligoceno medio-superior que<br />

continúa hasta el Pleistoceno. En el Altiplano septentrional se<br />

consideran tres secuencias, la primera ubicada al oeste de la falla<br />

de San Andrés, la segunda entre las fallas San Andrés y Coniri, y la<br />

tercera al este de la falla Coniri.<br />

En el sector central y oriental del Altiplano septentrional, el Ciclo<br />

Andino II se inicia con el Grupo Corocoro (Ahlfeld, 1946). Este<br />

autor reconocía en el “Sistema de Corocoro” cuatro unidades que<br />

incluyen a las “areniscas de Coniri” (Formación Coniri), “estratos<br />

de Ramos” (Formación Kollu Kollu), y otras unidades de lutitas,<br />

areniscas y tobas (formaciones Caquiaviri y Rosapata)<br />

La Formación Coniri (Douglas, 1914), corresponde a una<br />

secuencia continental aluvial y fluvial depositada en una cuenca de<br />