Judicial ReEngineering

Judicial ReEngineering

Judicial ReEngineering

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

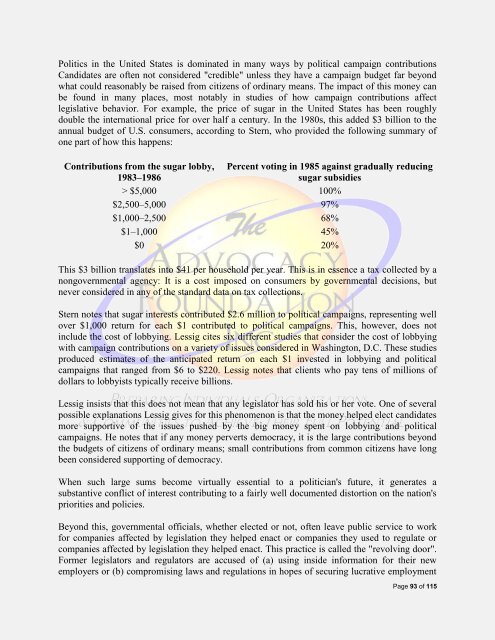

Politics in the United States is dominated in many ways by political campaign contributions<br />

Candidates are often not considered "credible" unless they have a campaign budget far beyond<br />

what could reasonably be raised from citizens of ordinary means. The impact of this money can<br />

be found in many places, most notably in studies of how campaign contributions affect<br />

legislative behavior. For example, the price of sugar in the United States has been roughly<br />

double the international price for over half a century. In the 1980s, this added $3 billion to the<br />

annual budget of U.S. consumers, according to Stern, who provided the following summary of<br />

one part of how this happens:<br />

Contributions from the sugar lobby,<br />

1983–1986<br />

Percent voting in 1985 against gradually reducing<br />

sugar subsidies<br />

> $5,000 100%<br />

$2,500–5,000 97%<br />

$1,000–2,500 68%<br />

$1–1,000 45%<br />

$0 20%<br />

This $3 billion translates into $41 per household per year. This is in essence a tax collected by a<br />

nongovernmental agency: It is a cost imposed on consumers by governmental decisions, but<br />

never considered in any of the standard data on tax collections.<br />

Stern notes that sugar interests contributed $2.6 million to political campaigns, representing well<br />

over $1,000 return for each $1 contributed to political campaigns. This, however, does not<br />

include the cost of lobbying. Lessig cites six different studies that consider the cost of lobbying<br />

with campaign contributions on a variety of issues considered in Washington, D.C. These studies<br />

produced estimates of the anticipated return on each $1 invested in lobbying and political<br />

campaigns that ranged from $6 to $220. Lessig notes that clients who pay tens of millions of<br />

dollars to lobbyists typically receive billions.<br />

Lessig insists that this does not mean that any legislator has sold his or her vote. One of several<br />

possible explanations Lessig gives for this phenomenon is that the money helped elect candidates<br />

more supportive of the issues pushed by the big money spent on lobbying and political<br />

campaigns. He notes that if any money perverts democracy, it is the large contributions beyond<br />

the budgets of citizens of ordinary means; small contributions from common citizens have long<br />

been considered supporting of democracy.<br />

When such large sums become virtually essential to a politician's future, it generates a<br />

substantive conflict of interest contributing to a fairly well documented distortion on the nation's<br />

priorities and policies.<br />

Beyond this, governmental officials, whether elected or not, often leave public service to work<br />

for companies affected by legislation they helped enact or companies they used to regulate or<br />

companies affected by legislation they helped enact. This practice is called the "revolving door".<br />

Former legislators and regulators are accused of (a) using inside information for their new<br />

employers or (b) compromising laws and regulations in hopes of securing lucrative employment<br />

Page 93 of 115